Abstract

The objective of the present study was to investigate parents’, teachers’ and principals’ views on parental involvement (PI) in Secondary Education Schools in Greece. The research was based on a survey among parents (n = 54), teachers (n = 84) and principals (n = 12) in twelve Secondary Education Schools in Magnesia Region in central East Greece. Different views between each group were exhibited on PI in educational issues, decision making or creating links and communication between the school and the local community. Teachers expressed the view that workload and parental attitudes are factors which discourage parental involvement in their school units. Parents felt that teachers’ professionalism, lack of teachers’ training on parental involvement and parents who hesitate talking to teachers were significant barriers for PI in their school units. School principals agreed with parents and teachers on the barriers established due to teachers’ professionalism and parents’ hesitation in talking to teachers as significant factors which discourage PI in their school units. Contrarily to teachers’ views, school principals expressed their willingness to increase PI in teachers’ and school evaluation. School leaders should explore the possibility of organising meetings with teachers and parents to reduce barriers and misconceptions, paving the way for communication between the school unit and parents, increasing the positive outcomes of PI in school management and students’ success.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, there has been a wide interest concerning the degree and nature to which parents are involved in their children’s education [1,2,3,4,5]. Parental involvement in Secondary Education has come under immense scrutiny and criticism by both teachers and principals. Although, to some extent, both parties agree that parental involvement in Secondary Education plays an integral role in enhancing students’ performance, they also believe that parental involvement undermines the teaching profession’s autonomy when it concerns taking professional decisions in sophisticated situations [6]. It is for this reason that depending on their experience, training and personality traits, some teachers and Principals may have negative attitudes on parental involvement (PI). Furthermore, teachers believe that parental involvement may result in the deterioration of relationship between parents and learners [7].

Another problem is how parents, teachers and school leaders perceive parental involvement. There is some evidence to suggest that parents, teachers and principals may have a somewhat contrasting view on the essence of parental involvement in Secondary Education and what parental involvement ought to entail [8,9]. Although parents and teachers share similar targets, parents’ and teachers’ role regarding children’s education may vary. For example, both groups may share common goals for students’ education, sociability and personality but parents may be focused on their own children whereas teachers should also consider their classroom/school unit. Furthermore, differences are expected within each group, i.e., cultural diversity, sociability, social background and other personal and demographic parameters may have an effect on what parents and teachers view as parental involvement and their share in the responsibly for school–family collaboration [10,11].

In other words, teachers and parents may exhibit diverse views on what PI is and how it can be encouraged in their school. The perspective of the “Professionals” may be quite different from the perspectives and views of parents when it comes to PI in schools [6] and the complexity of parameters which create barriers to effective parental involvement [12,13,14,15]. In fact, parents and teachers hold positive views on parental involvement, but there are differences among the two parties on the nature and level of involvement [16,17,18], particularly when PI refers to educational issues and school management [15,19,20,21,22]. For example, teachers can be less willing to involve parents in curriculum issues and decision making of their school [6]. Parents, on the other hand, feel that their involvement is limited in issues like financing events and school expenses and that they seldom have the opportunity to participate fully in important educational issues and the decision-making of their children’s school, such as curriculum, school and teachers’ evaluation [8,9,10,11]

Irrespective of any differences in the perception of stakeholders, all groups agree that parental involvement has a positive effect on students’ academic success and behaviour [23]. Depending on several factors, parental involvement can take many forms. Generally, parental involvement consists of three basic aspects, namely: academic socialization, home-based involvement and school-based involvement. Home-based involvement entails parents’ learning activities at home such as talking about school, helping with and checking homework; school-based involvement entails certain activities as implemented by school such as taking part in school activities, attending class meetings and meeting with teachers; academic socialization, on the other hand, entails parents’ faith and expectations about their loved one’s education [3]. Encouraging and supporting parental involvement in their children’s education is considered as a feature of successful school management with positive outcomes for stakeholders like teachers and learners [24,25]. Parental involvement has been linked with children’s academic success; their increased motivation for learning and their attitude towards school in general as well as their emotional well-being and development fosters better classroom behavior and reduction of school dropouts [26,27]. In general, collaboration among parents, teachers and school personnel is related to positive outcomes [28,29]. Findings have supported the view that when parents participate in the decision-making process of their school, they experience greater feelings of ownership and are more committed to supporting the school’s mission, resulting in improved educational outcomes [12,23,28,29,30,31,32]

School principals’ contribution can determine the level and quality of communication between school management and teachers [33,34] and also between parents and school, shaping the nature of teachers’ attitudes and encouraging parental involvement in their school [35]. Principals can maintain an open-door approach with parents organizing and facilitating parent–teacher involvement.

In the past, initiatives to improve pparental involvement in Greek schools were erratic and only recently was the significance of parental involvement officially emphasized by the educational authorities in Greece [36]. Greece has a centralized educational system which sets the rules and goals for parental involvement in schools. Parents’ participation in school activities has been formalized with the obligatory establishment of a Parents’ Association in every school unit [37]. After a series of initiatives which aimed to improve collaboration between parents and schools, parental involvement in Greece is still developing and shaped according to the culture, values and perceptions of teachers, principals and parents. For example, the perceptions for the type and level of parental involvement may vary between schools and parents [25]. In spite of variability in the views, attitudes and perceptions, each group values parental involvement, which can have several benefits for students and school in general. Irrespective of the attitude, one thing for certain is that parental involvement has a critical role in the quest for quality education [38]. The recently implemented legislative initiatives for parental involvement in Greece create unprecedented opportunity for parents, Principals and teachers to build school–family partnership and collaboration. Unfortunately, efforts to improve parents-school communication and collaboration may have been hindered by the country’s economic problems, characterized by teachers’ relocations after school closures, employment freezes, rising number of teachers’ retirements, increased size of classrooms and the simultaneous decrease in the number of seasonally employed teachers [33,39,40], reduction in the teaching workforce in Greece [34]. Under such conditions, teachers may be working with increased workload and have limited time for collaborating with parents coupled with limited funding, partly leading to a parallel education system being set up. Nowadays, the majority of students attend private classes or private tuition sessions in the afternoons and weekends. The thriving of private tuition in Greece and the competition for getting good grades in the national University Entrance Exams has shifted the pressure from the school to private tuition. Furthermore, Greek parents may have difficulty in following the current Curriculum-based homework of their children and may prefer and trust private tuition for their children’s education. This situation may reduce the affinity for parental involvement in public schools. Research on the views of teachers, parents and Principals on parental involvement can be employed by school leaders to improve effective parental involvement and identify any potential barriers. The aim of the present work was to investigate parents’, teachers’ and Principals’ views on parental involvement in Secondary Education Schools in Greece.

2. Materials and Methods

Parents, teachers and principals from twelve public Secondary Education School units in the region of Magnesia in Central East Greece participated in the present work.

Principals were approached and informed about the aim of the present research work and the survey was distributed to teachers and principals in each school.

A questionnaire with reported high internal consistency and previously used and validated in a relevant research in Greek schools [41] was used to survey the views of Parents, Teachers and Principals on the issue of Parental involvement. The questionnaire contained 25 items which were used to assess participants’ views on parental involvement, the level of communication between school and parents, the benefits of parental involvement, the current level of parental involvement and the role of leadership. The answers were provided on a five-point scale (ranging from 0 = disagree to 5 = fully agree).

Schools’ Parents Associations were approached and also informed about the aim of the present research work. The survey was distributed to parents during a regular monthly meeting of the Parental Association in each school.

One hundred and fifty (150) completed questionnaires were collected (parents = 54, teachers = 84 and principals = 12). The distributed questionnaires included questions on parents’, teachers’ and Principals’ views on parental involvement.

Data were analyzed and tested for normal distribution with SPSS (version 14.01). When ANOVA indicated a significant difference, a Scheffe comparison among principals, teachers and parents was used.

3. Results

The demographic data of principals and teachers and parents who participated in the survey are presented in Table 1. Principals were grouped according to gender, level of education, age and years of work experience. As evident from the data in Table 1, most principals (nine principals) had teaching experience of 26 to 30 years; only two principals had teaching experience of more than 30 years (31–35 years), whereas only one had fewer than 26 years teaching experience. Ten principals had served for more than four years as school principals whereas only two had served less than four years. In terms of gender, eight principals were male and four females. Eight principals held a postgraduate degree. Ten principals were aged between 51 and 60, one was past 60 years and one was below 51 years.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the school principals and teachers of the sample.

Parents were grouped according to their gender, level of education and years participating in the School Parents Association. Out of the 54 parents taking part in the survey, 22 were male and 32 were female. In terms of their years participating in the School Parents Association, 31 parents had an experience of between 0 and 2 years, 22 had an experience of 2–5 years and only one parent had more than five years’ experience.

Out of the 84 teachers taking part in the survey, 40 were males and 44 were females. Only one teacher had working experience of fewer than five years. Principals’, teachers’ and parents’ views on the existence of a school policy encouraging parental involvement, are presented in Table 2. All principals believed that their school had adequate policies for encouraging parental involvement. Of the teachers, 69% believed that their school had policies for encouraging parental involvement, with 31% of them believing that their school lacked such policies. A large percentage of parents (61.1%) stated that their children’s school lacked policies for encouraging parental development, with only 38.9% of them acknowledging the presence of such policies.

Table 2.

Answers to the question “does your school have policies for encouraging parental involvement?” Principals’, teachers’, and parents’ opinion on whether the school in question had policies for encouraging parental involvement. X2 test was used to assess the significance of differences in views of Principals (n = 12), Teachers (n = 84) and Parents (n = 54).

Principals’, teachers’ and parents’ views on parental involvement in their school, are presented in Table 3. When ANOVA indicated significant difference, a Scheffe comparison among Principals, teachers and parents was used. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different groups. All parties agreed to “informing parents on School’ performance” (p = 0.315), and in “participation in monthly meetings” (p = 0.168). There were significant differences in the views of teachers, parents and principals on “involvement in School’s educational issues” (< 0.001), on “involvement in decision making” (< 0.001) and on the “involvement in creating links between the School and local community” (< 0.001).

Table 3.

Answers to the question “do you agree on parental involvement in your school in following issues?” Table 3 illustrates the average score of the survey on the question on whether participants agree with their school’s parental involvement in issues such as informing parents on the school’s performance, participation of parents in monthly meetings, involvement in school educational issues, decision making, and in creating links and communication between the school and local community. Views of Principals (n = 12), Teachers (n = 84) and Parents (n = 54). When ANOVA indicated significant difference, a Scheffe comparison among Principals, teachers and parents was used. Different superscripts (letters a or b with an asterisk) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different groups. NS=non significant difference between each group.

Principals’, teachers’ and parents’ views on the areas in which parental involvement should be encouraged are presented in Table 4. When ANOVA indicated a significant difference, a Scheffe comparison among principals, teachers and parents was used. The different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among the different groups. The results were as follows: School’ social events (p = 0.315), sports’ events (NS), enriching School’s curriculum (< 0.001), innovation in teaching methods (NS), teachers’ evaluation (< 0.001), School’s evaluation (< 0.001).

Table 4.

Answers to the question “would you agree to encourage parental involvement in your school in following issues?” When ANOVA indicated significant difference between Principals (n = 12), Teachers (n = 84) and Parents (n = 54), post hoc Scheffé’s test was performed. Different superscripts (letters a or b with an asterisk) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among different groups. NS = non significant difference between the groups.

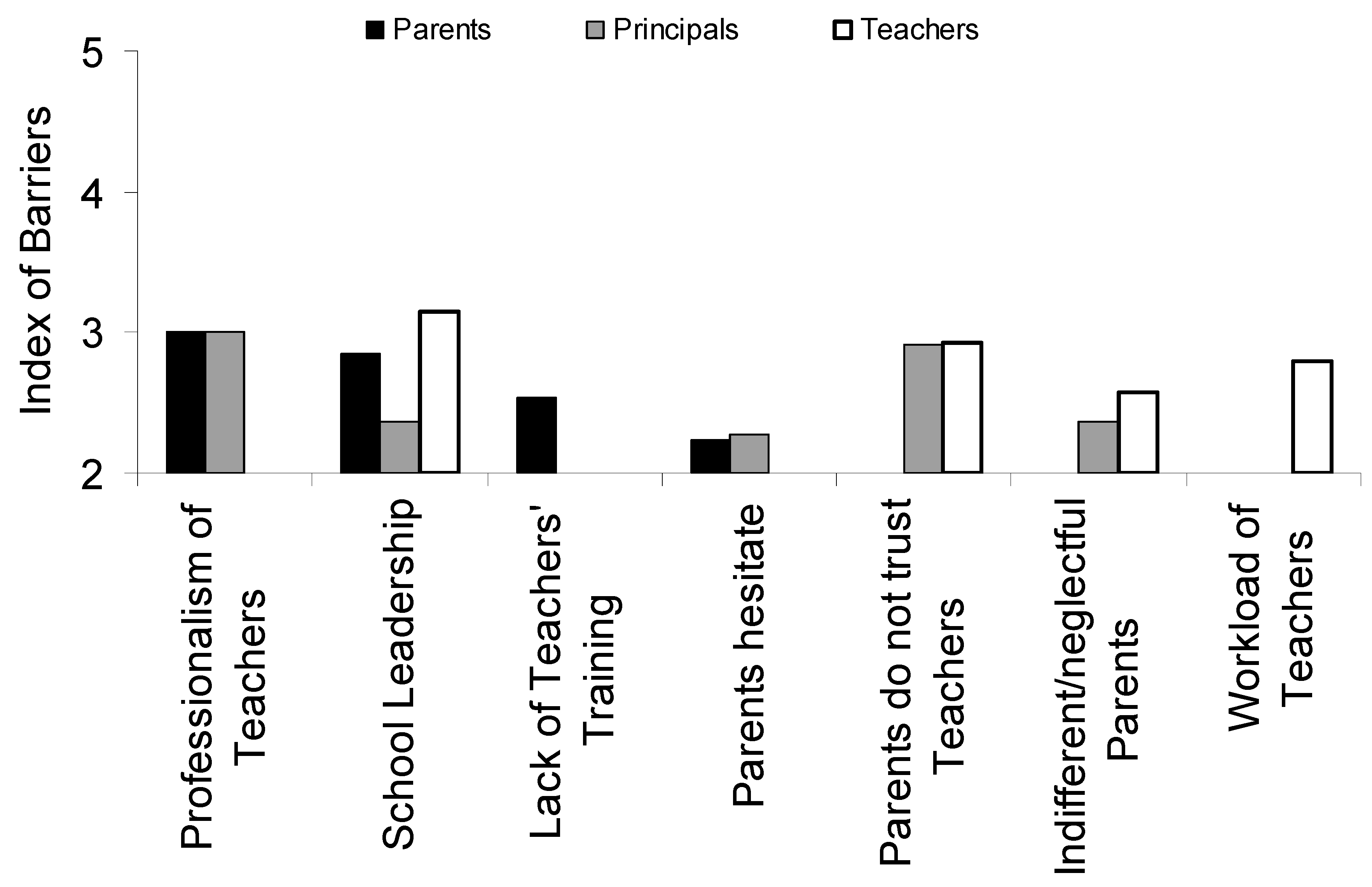

Some differences in the views of each group were also exhibited on the perceptions of principals’, teachers’ and parents’ on the existence of barriers to parental involvement in their school units (Figure 1). Teachers expressed the view that their workload and the parents (who did not trust their school or were indifferent) as factors which discourage parental involvement. Parents felt that teachers’ professionalism, lack of teachers’ training on parental involvement and parents who hesitate to talk to teachers were significant barriers to parental involvement. School principals agreed with parents and teachers on the barriers established due to teachers’ professionalism and parents’ hesitation in talking to teachers as significant factors which discourage parental involvement (Figure 2).

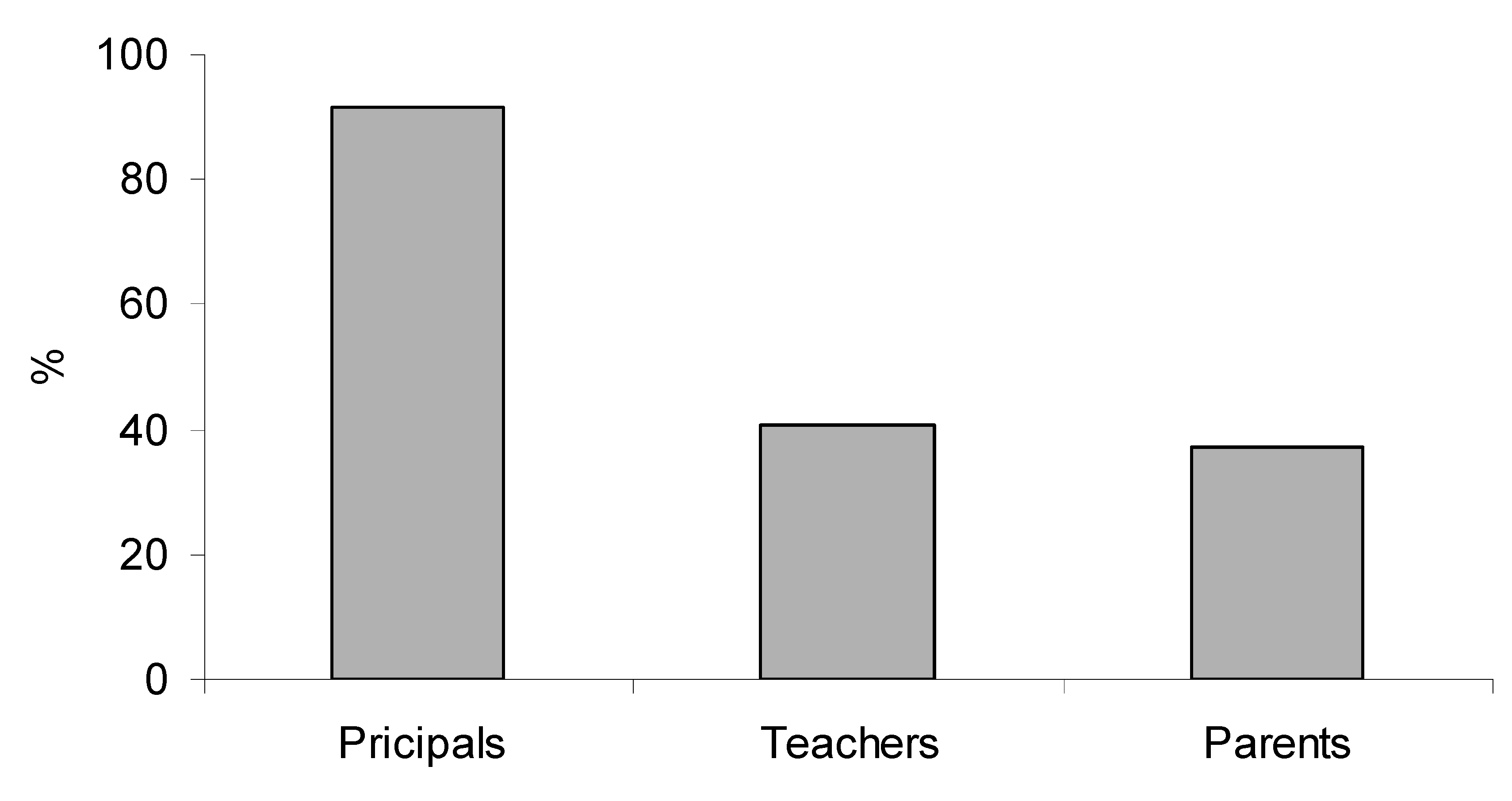

Figure 1.

Percentage of Principals, Teachers and Parents who had the perception of School Principals’ positive contribution in effectively motivating teachers and parents.

Figure 2.

Principals’, teachers’ and parents’ perceptions Parental Involvement (PI) barriers in their School unit. Teachers were asked to indicate their level of Agreement/disagreement on potential barriers for PI. The Y axis presents the index of different barriers. The base line is an index score = 2 which corresponds to “Neither agree nor disagree”. Scores > 2 indicates participants’ perception on the magnitude of each barrier for PI.

4. Discussion

All the principals who participated in the present work claimed that their school was successfully implementing an active policy on parental involvement. On the other side, teachers and parents felt differently, with 69% of the teachers and only 38.9% of parents confirming Principals’ statements of a satisfactory level of parental involvement in their school (Table 2). These differences may reflect differences in their views on parental involvement. This difference between teachers and parents was observed on the answers to the question about the areas that parental involvement should be encouraged. Parents gave a high priority to their involvement in educational issues and participating in decision making. Contrarily to parents’ views, teachers scored much lower on this type of parental involvement in their school, expressing a view which reflects their resilience for parental involvement in demanding issues such as educational issues and teachers’ evaluation by parents (Table 3). Similar discrepancies in parents’, teachers’ and school leaders’ views have also been observed in other countries, reflecting a gap among each group in terms of their expectations on what parental involvement should entail [2,8,9]. At an international level, parental involvement is an emerging issue. Teachers may be reluctant to engage in parental involvement when it comes to their professional work. Teachers’ workload, school culture, school leadership can also inhibit teachers’ willingness to share their professional autonomy [19,20] and this is what teachers and principals argue when they suggest that parents should not be greatly involved on educational aspects [6,10,21].

In the present work, differences in the views between school and parents were observed regarding the form and magnitude of parental involvement. Each group had varying opinions on whether parental involvement in school management should entail involvement in educational issues, decision making or creating links and communication between the school and the local community. The results are in agreement with previous results reported from Greece [16,17]. Surprisingly, differences were also observed between teachers and Principals. Contrarily to teachers’ views, School Principals and parents expressed their willingness to increase parental involvement in teachers’ assessment and the evaluation of the effectiveness of their school (Table 4).

Principals, teachers and parents hold a positive view on parental involvement, agreed on the benefits of establishing a communication between school and parents with frequent meetings and the benefits of collaboration for organizing social or sport school events. Nevertheless, each group expressed different views on the areas that parents should be involved. The enhanced willingness of Principals to encourage parental involvement may reflect their leadership vision in engaging school-family collaboration, implementing at the same time the legislative guidelines on parental involvement. In fact, diversity within in each group and between each group, on the issue of PI have been reported in other countries [2,4,10,11,28,35].

Differences were also exhibited on the perceptions of each group about the existence of barriers for parental improvement in their school units. Barriers to parental involvement can be due to a variety of parameters. For example, teachers and parents may have difficulty in participating in some types of involvement and teachers may prefer to keep a distance towards parents to ensure that they will not step in their job [6]. Similar problems are commonly observed, reflecting the differences in perspectives between the “professionals” and parents [12,13,15,22].

The results of the present work indicate that parents, teachers and Principals agree on the essence of parental involvement in Secondary Education. However, they have varied opinions on the form and degree to which parents should be involved. For example, in response to the question “do you agree on parental involvement in your school in the following issues?”, all stakeholders (parents, teachers and principals), to a large extent, agreed that it is ultimately crucial to inform parents on issues related to school performance. All groups agreed that parents’ participation in monthly meetings was also essential while on the other hand, teachers argued that parents should not have a great influence on all educational aspects.

Parental involvement in school management has been viewed and investigated from many perspectives. Relevant data provide support in the notion that parental involvement is a significant contributing factor in various aspects such as effective school management and students’ academic performance [19,20,21,22]. Parents, teachers and principals in Greece generally hold a positive attitude to parental involvement [16,17] and this was also confirmed in the present work. Nevertheless, the results of the present work indicate some differences in parents’, teachers’ and Principals’ views on what is the current situation and on which areas should parental involvement be enhanced in their school.

The results of the present work indicate that teachers generally had a positive attitude on parental involvement, but their views were reversed on specific types of parental involvement which interfere with their work. For example, teachers portrayed a positive attitude for parental involvement regarding monthly school meetings, were parents among other issues will be informed on the academic performance of their children, about technical or financial issues which require urgent attention, financial support by parents who may be called to cover the cost of central heating—A situation which became a norm in Greek schools during to long period of financial crisis experienced in the Country. Teachers also had a positive attitude in terms of parental involvement in social and sports events. Nevertheless, contrarily to these positive views, teachers were reluctant to encourage parental involvement when it comes to the evaluation of their teaching work and the evaluation of their school. Teachers’ reluctance to be exposed to some type of parental involvement may be based on a lack of teacher training in the demanding process of parental involvement. In Greece and other countries, teachers lack training in their formal professional education for enabling and preparing them to engage and encourage the creation of effective communication and interaction with parents.

Effective communication and parental involvement require teachers’, parents’ and school leaders’ willingness to engage in demanding processes. Teachers may experience a range of stressful and demanding conditions in their profession [42] and parental involvement can be a stressful experience if teachers are not prepared, guided and trained for this [43,44,45].

The results presented are based on the perceptions and views of a small sample of School Principals, teachers and parents. Nevertheless, this study does highlight the importance of examining the perceptions of teachers, parents and school principals on parental involvement in their school units. Encouraging parental participation may not progress if each group has different perceptions of what parental involvement should entail. The value of the present work lies on shedding some light on each group’s views on parental involvement. The results of the present work could be useful for policy makers and school leaders who should further investigate the issue of effective school communication and encourage effective parental involvement and collaboration between school and parents.

School leadership can make a difference with the initiation of policies which could encourage parents to be involved and the formulation of in-service training activities which could improve teachers’ competence and attitudes in parental involvement [6,15,19,20,21,22,35,38] Parental Involvement can be a tool for increasing educational outcomes and performance of schools [1,2,4,23,27]. Towards this can also serve the development of a strategic parental involvement plan to encourage parents becoming more engaged in their children’s education, including parents and teachers communicating and partnering with one another and developing a climate of communication and cooperation between school and family [5,12,42,43,44,46,47].

5. Conclusions

Parents, teachers and principals who participated in the present work had a positive view on the issue of parental involvement. Nevertheless, the extent to which parents should be involved in school management was met with varied opinions. Differences were also observed between teachers and Principals. Contrary to teachers’ views, school Principals expressed their willingness to increase parental involvement in teachers’ assessment and the evaluation of the effectiveness of their school. School leaders could explore the possibility of organising meetings with teachers and parents to reduce barriers and misconceptions, paving the way for effective communication between the school unit and parents, increasing the positive outcomes of parental involvement in school management and students’ success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and A.P.; Data curation, A.P.; Investigation, A.P.; Methodology, S.A. and A.P.; Resources, A.P.; Supervision, S.A.; Validation, S.A. and A.P.; Writing–original draft, S.A. and A.P.; Writing–review & editing, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mapp, K.L.; Johnson, V.R.; Strickland, C.S.; Meza, C. High school family centres: Transformative spaces linking schools and families in support of student learning. Marriage Family Rev. 2008, 43, 338–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.M. Broadening the myopic vision of parental involvement. Sch. Community J. 2009, 19, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A.; Boyle, A.; Sadler, S. Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, E.; Dotterer, A.M. Parental involvement and adolescent academic outcomes: Exploring differences in beneficial strategies across racial/ethnic groups. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1332–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.M.; Locklear, L.A.; Watson, N.A. The Role of Parenting in Predicting Student Achievement: Considerations for School Counselling Practice and Research. Prof. Couns. 2018, 8, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeck, U.D.K. We are the professionals’: A study of teachers’ views on parental involvement in school. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2010, 31, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.V.; Tuazon, A.P. School practices in parental involvement, its expected results, and barriers in public secondary schools. Int. J. Educ. Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Landeros, M. Defining the ‘good mother’and the ‘professional teacher’: Parent–teacher relationships in an affluent school district. Gend. Educ. 2011, 23, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.A.; Cárdenas, C.A.; Romero, P.O.; Hernández, M. Los Padres de Familia y el Logro Académico de los Adolescentes de una Secundaria en Milpa Alta, Ciudad de México. Inf. Tecnol. 2017, 28, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bilton, R.; Jackson, A.; Hymer, B. Cooperation, conflict and control: Parent–teacher relationships in an English secondary school. Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixsen, S.; Danielsen, H. Great expectations: Migrant parents and parent-school cooperation in Norway. Comp. Educ. 2020, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G.; Lafaele, R. Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educ. Rev. 2011, 63, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, G.; Blackwell, I. Barriers to parental involvement in education: An update. Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padak, N.; Rasinski, T.V. Welcoming schools: Small changes can make a big difference. Read. Teach. 2010, 64, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartmeier, M.; Gebhardt, M.; Dotger, B. How do teachers evaluate their parent communication competence? Latent profiles and relationships to workplace behaviors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 55, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, K.; Koutrouba, K.; Babalis, T. Parental involvement in secondary education schools: The views of parents in Greece. Educ. Stud. 2011, 37, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutrouba, K.; Antonopoulou, E.; Tsitsas, G.; Zenakou, E. An investigation of Greek teachers’ views on parental involvement in education. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2009, 30, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besi, M.; Sakellariou, M. Teachers’ Views on the Participation of Parents in the Transition of their Children from Kindergarten to Primary School. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.L. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.L. Attainable goals? The spirit and letter of the No Child Left Behind Act on parental involvement. Sociol. Educ. 2005, 78, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.P. Educating preservice teachers for family, school, and community engagement. Teach. Educ. 2013, 24, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Chiliya, N.; Musara, M. Theory of planned behaviour to predict parents’ awareness and intention to participate in school governing body elections. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 12, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeynes, W.H. Effects of Parental Involvement and Family Structure on the Academic Achievement of Adolescents. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2005, 37, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.E.; Craft, S.A. Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.B.; Ray, J.A. Home, School and Community Collaboration: Culturally Responsive Family Involvement; Sage Publications Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, W. A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Different Types of Parental Involvement Programs for Urban Students. Urban Educ. 2012, 47, 706–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeynes, W.H. A meta-analysis: The relationship between parental involvement and African American school outcomes. J. Black Stud. 2016, 47, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A. Home school relations in Singaporean primary schools: Teachers’, parents’ and children’s views. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2019, 45, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K.V.; Walker, J.M.; Sandler, H.M.; Whetsel, D.; Green, C.L.; Wilkins, A.S.; Closson, K. Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. Elem. Sch. J. 2005, 106, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X. Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A growth modeling analysis. J. Exp. Educ. 2001, 70, 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.; Muls, J.; De Backer, F.; Lombaerts, K. Middle school student and parent perceptions of parental involvement: Unravelling the associations with school achievement and wellbeing. Educ. Stud. 2019, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajša-Žganec, A.; Merkaš, M.; Šakić Velić, M. The relations of parental supervision, parental school involvement, and child’s social competence with school achievement in primary school. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Abdullah, A.G.K. Parents’ involvement in Malaysian autonomous schools. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Chandolia, E.; Anastasiou, S. Leadership and Conflict Management Style are Associated with the Effectiveness of School Conflict Management in the Region of Epirus, NW Greece. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K.; Abramovitz, R.; Daod, S.; Awad, Y.; Khalil, M. Teachers’ perceptions of school principals’ leadership styles and parental involvement–the case of the Arab education system in Israel. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 2016, 11, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthacou, Y.; Babalis, T.; Stavrou, N. The Role of Parental Involvement in Classroom Life in Greek Primary and Secondary Education. Psychology 2013, 4, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lazaridou, A.; Kassida, A.G. Involving parents in secondary schools: Principals’ perspectives in Greece. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2015, 29, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Valdivia, I.M.; Chavez, K.L.; Schneider, B.H.; Roberts, J.S.; Becalli-Puerta, L.E.; Pérez-Luján, D.; Sanz-Martínez, Y.A. Parental involvement and the academic achievement and social functioning of Cuban school children. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 34, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, N.; Anastasiou, S.; Goloni, V. Professional burnout and job satisfaction among physical education teachers in Greece. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2014, 3, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidis, K.; Anastasiou, S.; Mavridis, S. Cross country variability in salaries’ changes of teachers across Europe during the economic crisis. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on International Business (ICIB), University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece, 23–25 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koiliakou, D. The role of leadership in Managing communication between the school unit and Parents. Master’s Thesis, The Hellenic Open University, Aristotelous, Greece, 2015. Available online: https://apothesis.eap.gr/handle/repo/29988?locale=en (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Anastasiou, S.; Papakonstantinou, G. Factors affecting job satisfaction, stress and work performance of secondary education teachers in Epirus, NW Greece. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 8, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeou, L.; Roussounidou, E.; Michaelides, M. I feel much more confident now to talk with parents: An evaluation of in-service training on teacher parent communication. Sch. Community J. 2012, 22, 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Babalis, T.H.; Katsaouni, K. Family-school relations. Parents’ role. Matters Educ. Plan. 2011, 4, 148–166. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou, S.; Garametsi, V. Teachers’ Views on the Priorities of Effective School Management. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.; Al Sheryani, Y.; Yang, G.; Al Rashedi, A.; Al Sumaiti, R.; Al Mazroui, K. The Effects of Teachers’, Parents’, and Students’ Attitudes and Behavior on 4th and 8th Graders’ Science/math Achievements: A model of School Leaders’ Perspectives. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2019, 1, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.L.; Sanders, M.G.; Sheldon, S.B.; Simon, B.S.; Salinas, K.C.; Janson, N.R.; Hutchins, D.J. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action; Corwin Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).