Gateway to Outdoors: Partnership and Programming of Outdoor Education Centers in Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Education Programs in Outdoor Education Centers

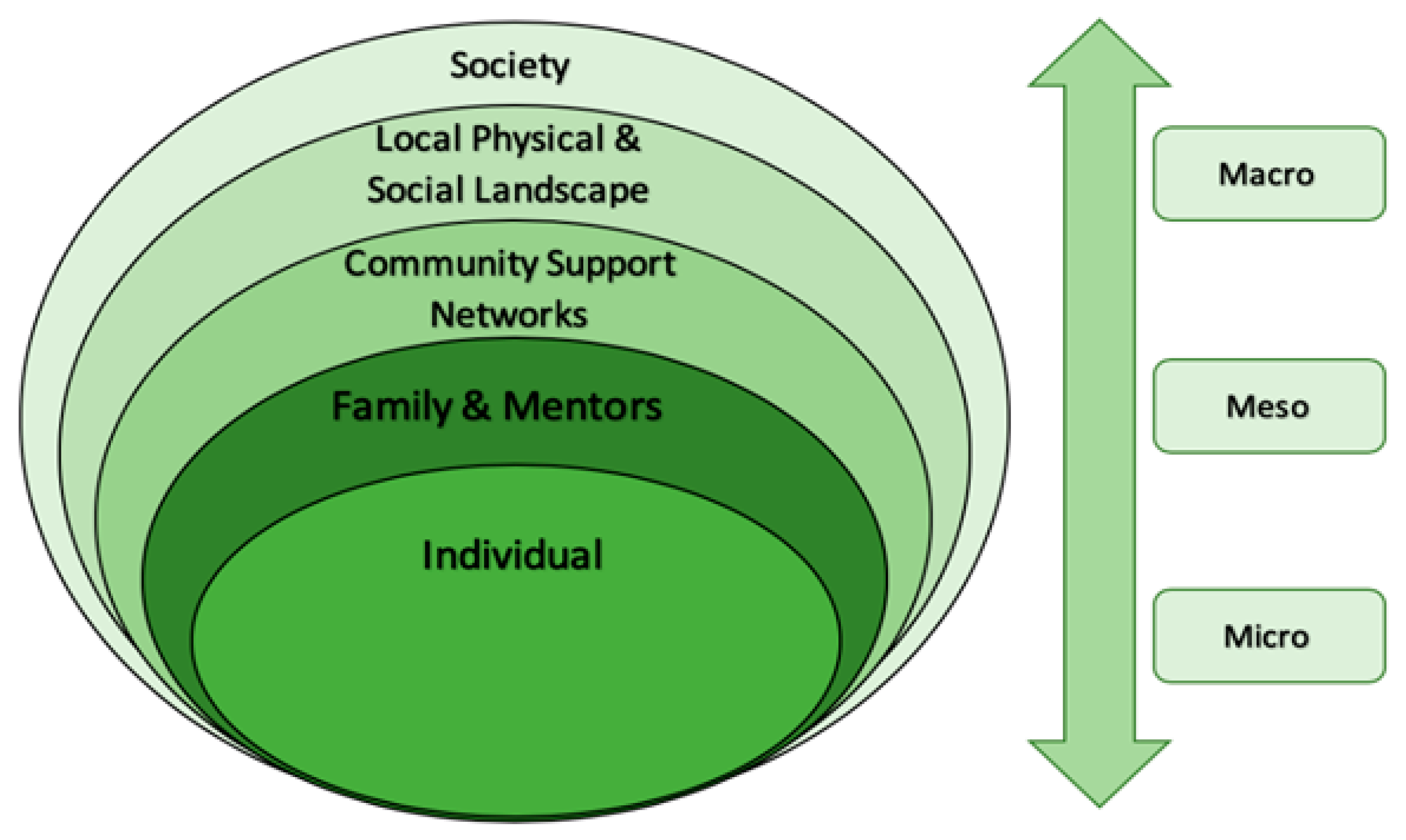

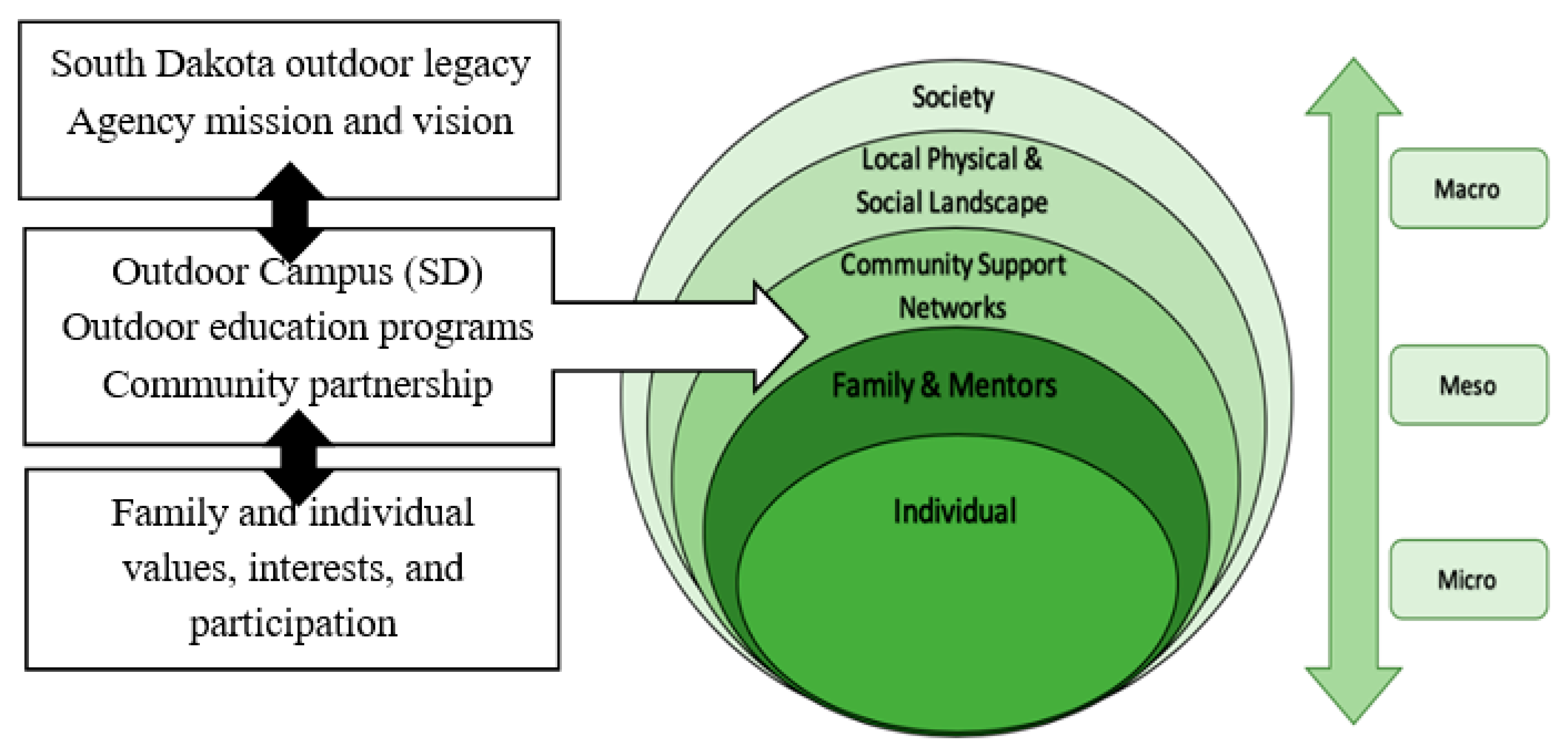

2.2. Social–Ecological Model and Partnership

3. Methods

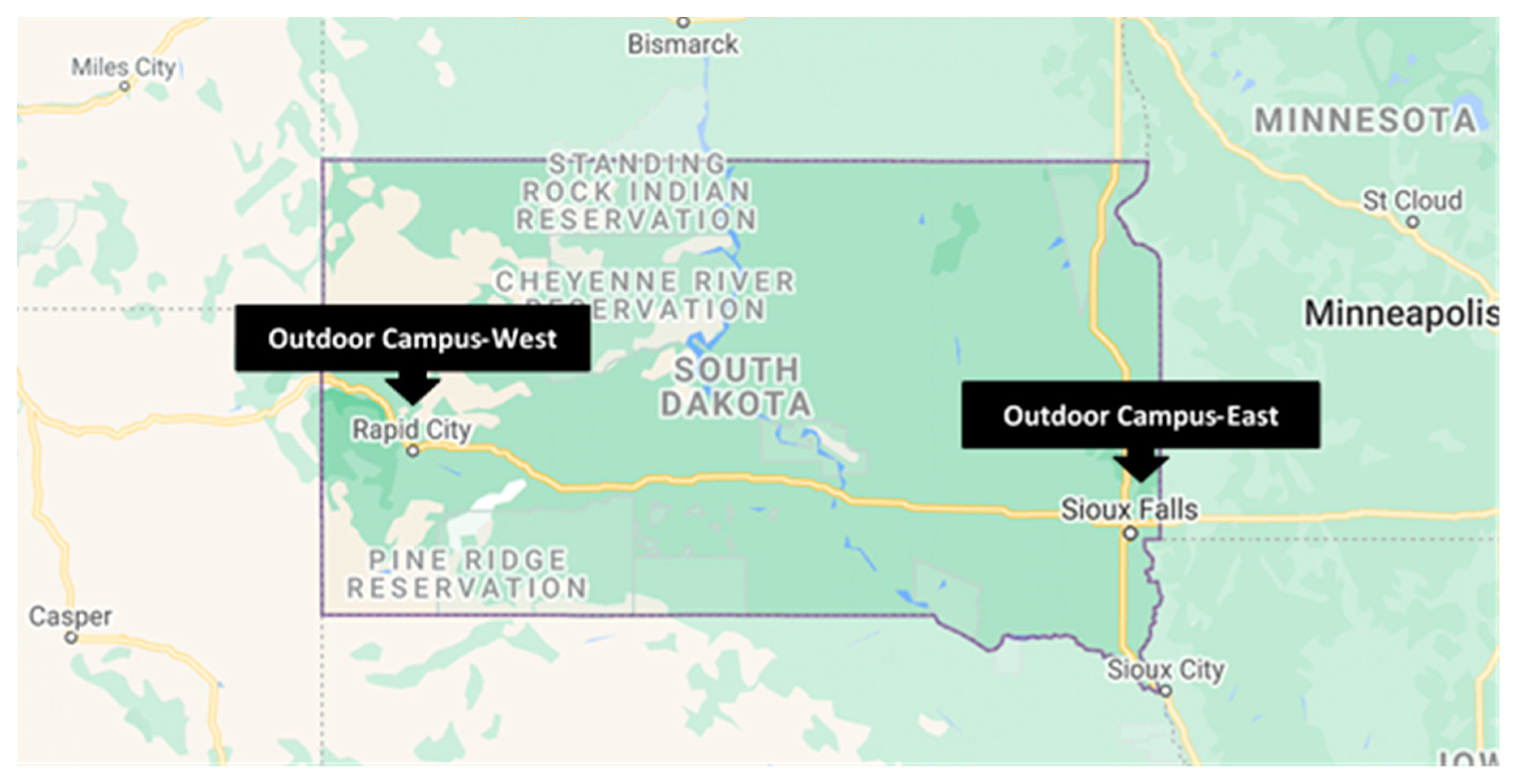

3.1. Study Location

3.2. Participants & Data Collection

3.3. Interview Structure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Gateway to Our Outdoor Legacy

“One of the benefits in working in an outdoor campus setting is that you have that recognizable footprint within the community and in the local area so the state, regional, national organizations that are trying to do similar things to what we’re doing come to us.”

4.2. Working Together for Outdoor Education

4.2.1. Formal Partnership

4.2.2. Programmatic Partnership

“I takeout first-time youth and adult hunters, and I take them to the gun range where we shoot and get them comfortable with the gun, and then I actually take them on an actual hunt where they actually harvest and process a deer.”

4.2.3. Finding Balance in Partnerships

“(A non-profit) have kids that pay to come attend their (summer) camp, but they bring them here to do fishing or archery. But it’s still bringing people, and allowing us to introduce them (youth) to the outdoors. Even though we are not profiting on it and they’re making a profit, it’s still a collective audience that they are bringing to us that wouldn’t normally be here. We get hundreds of kids that come in through another organization here.”

“We know that some of the people involved with a homegrown group are interested in growing their own food from farm to table and field to table. Well, if you’re harvesting your own food and you’re raising your own chickens, maybe then you’ll go hunting. There’s a similar connection there. I call them gateway classes. We have a common interest, so let’s see if we can cross over a little bit.”

4.3. Challenges and Opportunities in Programming

4.3.1. Common Challenges in Outdoor Education Programs

4.3.2. Evolving Process of Outdoor Programs

“We tried to provide every opportunity and round them out as much as possible. … When it comes that they’re (participants) not just taking stuff from us, they’re using their resources. But when they come back and give back, it’s awesome! That’s the goal.”

“We started about five or six years ago now. I was at a conference, and they were talking about how the need is out there for home school how they are a collective audience. … There is a huge, huge following of home schools and they are all looking to tie into something that they can actually…away from home with their peers and stuff like that too so there has been a huge following. …Their flexibility is as far as schedules is a lot easier as well. Plus, the home school community is sometimes a little more open maybe to different ideas and stuff like that as well.”

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beames, S.; Ross, H. Journeys outside the classroom. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2010, 10, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B.; Gollob, J. The flexible recreationist: The adaptability of outdoor recreation benefits to non-ideal outdoor recreation settings. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2018, 21, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, M.; Muller, J. Mental health benefits of outdoor adventures: Results from two pilot studies. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, R.A.; Pontes, R. Parks, rhetoric and environmental education: Challenges and opportunities for enhancing ecoliteracy. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, C.; McCole, D. Understanding motivations of potential partners to develop a public outdoor recreation center in an urban area. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2014, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outdoor Industry Assciation. 2018 Outdoor Participation Report. Outdoor Industry Association. Available online: https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2018-outdoor-participation-report/ (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Byrne, R.; Dunfee, M. Evolution and Current Use of the Outdoor Recreation Adoption Model. Available online: https://cahss.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/RB_Evolution-and-Current-Use-of-the-ORAM_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Lekies, K.S.; Yost, G.; Rode, J. Urban youth’s experiences of nature: Implications for outdoor adventure recreation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, S.; Atencio, M. Building social capital through outdoor education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2008, 8, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Larson, L.; Yun, J. Advancing sustainability through urban green space: Cultural ecosystem services, equity, and social determinants of health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Dakota Game, Fish, and Parks. 2018 South Dakota Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. Available online: https://gfp.sd.gov/userdocs/docs/scorp18.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Bacon, J.M. Settler colonialism as eco-social structure and the production of colonial ecological violence. Environ. Sociol. 2019, 5, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. South Dakota Race and Ethnicity. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Lewis, J.; Hoover, J.; MacKenzie, D. Mining and environmental health disparities in Native American communities. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South Dakota Game, Fish, and Parks. Strategic Plan 2016–2020. Available online: https://gfp.sd.gov/userdocs/docs/strategic-plan-2.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Higgins, P.; Loynes, C. On the Nature of Outdoor Education. A Guide for Outdoor Educators in Scotland. Available online: http://www.docs.hss.ed.ac.uk/education/outdoored/guide_for_oe_in_scotland.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Decker, D.J.; Siemer, W.F.; Baumer, M.S. Exploring the social habitat for hunting: Toward a comprehensive framework for understanding hunter recruitment and retention. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2014, 19, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.J.; Powell, R.B.; Ardoin, N.M. What difference does it make? Assessing outcomes from participation in a residential environmental education program. J. Environ. Educ. 2008, 39, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, V.B.; Saw, S.M.; Finkelstein, E.; Wong, T.Y.; Tay, P.K.C. A new community-based outdoor intervention to increase physical activity in Singapore children: Findings from focus groups. Ann. Acad. Med. 2013, 42, 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Flett, R.M.; Moore, R.W.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Belonga, J.; Navarre, J. Connecting children and family with nature-based physical activity. Am. J. Health Educ. 2013, 41, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, J.; Timken, G. Outdoor pursuits in physical education: Lessons from the trenches. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2017, 88, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Dustin, D. Engaging youth in lifelong outdoor adventure activities through a nontraditional public school physical education program. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 85, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.K.; Williams, T. School-based experiential outdoor education: A neglected necessity. J. Exp. Educ. 2017, 40, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Connecting students to nature-how intensity of nature experience and student age influence the success of outdoor education programs. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 23, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, B.; Allen-Craig, S. What outcomes are we trying to achieve in our outdoor education programs? Aust. J. Outdoor Educ. 2007, 11, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, H.T.; McClain, L.R. Exploring the outdoors together: Assessing family learning in environmental education. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2014, 41, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, L.G.; Krasny, M.E. Outdoor adventure education: Applying transformative learning theory to understanding instrumental learning and personal growth in environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 2011, 42, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanski, A. Outdoor Education: Authentic Learning in the Context of Landscape Literacy Education and Sensory Experience. Perspective of the Where, What, Why, and When of Learning Environment. Available online: https://old.liu.se/ikk/ncu/ncu_filarkiv/Forskning/1.165263/AndersSzczepanski.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Jackson, L.E.; Daniel, J.; McCorkle, B.; Sears, A.; Bush, K.F. Linking ecosystem services and human health: The Eco-Health Relationship Browser. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, M.C.; South, E.C.; Branas, C.C. Nature-based strategies for improving urban health and safety. J. Urban Health 2015, 92, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, K.L.; Robbins, A.S. Metro nature, environmental health, and economic value. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wu, I.; Caneday, L. Using feasibility study as a management tool: A case study of Oklahoma State Park Lodges. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2018, 36, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Slyke, D.M.; Hammonds, C.A. The privatization decision: Do public managers make a difference? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2003, 33, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Ian, W.; Silvija, K.O.; Ivana, Ž.; Makedonka, S.; Nerys, J.; Johan, B. Partnerships for Urban Forestry and Green Infrastructure Delivering Services to People and the Environment: A Review on What They Are and Aim to Achieve. South-East Eur. For. 2016, 7, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Makopondo, R.O. Creating racially/ethnically inclusive partnerships in natural resource management an outdoor recreation: The challenges, issues, and strategies. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2006, 24, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Seekamp, E.; Cerveny, L.K. Examining USDA Forest Service recreation partnerships: Institutional and relational interactions. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2010, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liechty, T.; Mowen, A.J.; Payne, L.L.; Henderson, K.A.; Bocarro, J.N.; Bruton, C.; Godbey, G.C. Public parks and recreation managers’ experiences with health partnerships. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2014, 32, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, D.G.; Ham, L.L. Parternships. In Management of Park and Recreation Agencies; Van der Smissen, B., Moiseichik, M., Hartenburg, V.J., Eds.; National Recreation and Park Association: Ashburn, VA, USA, 2005; pp. 85–101. ISBN 9780975892633. [Google Scholar]

- Sausser, B.; Monz, C.; Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, J.W. The formation of state offices of outdoor recreation and an analysis of their ability to partner with federal land management agencies. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sausser, B.; Smith, J.W. Elevating Outdoor Recreation Together: Opportunities for Synergy between State Offices of Outdoor Recreation and Federal Land-Management Agencies, the Outdoor Recreation Industry, Non-Governmental Organizations, and Local Outdoor Recreation Providers. Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism at Utah State University. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c17e30fec4eb7fbe15edc2e/t/5c5080dacd83668ab22af4df/1548779757564/Elevating_Outdoor_Recreation_Together_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- South Dakota Game, Fish, and Parks. About Us. Available online: https://gfp.sd.gov/agency/ (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Manfredo, M.J.; Teel, T.L.; Don Carlos, A.W.; Sullivan, L.; Bright, A.D.; Dietsch, A.M.; Bruskotter, J.; Fulton, D. The changing socio-cultural context of wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.; Mitra, R.; Buliung, R.; Fusco, C.; Stone, M. Children’s outdoor playtime, physical activity, and parental perceptions of the neighborhood environment. Int. J. Play 2015, 4, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. What Is Environmental Education? Available online: https://www.epa.gov/education/what-environmental-education (accessed on 30 September 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Farrell, P.; Liu, H.-L. Gateway to Outdoors: Partnership and Programming of Outdoor Education Centers in Urban Areas. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110340

O’Farrell P, Liu H-L. Gateway to Outdoors: Partnership and Programming of Outdoor Education Centers in Urban Areas. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(11):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110340

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Farrell, Paige, and Hung-Ling (Stella) Liu. 2020. "Gateway to Outdoors: Partnership and Programming of Outdoor Education Centers in Urban Areas" Education Sciences 10, no. 11: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110340

APA StyleO’Farrell, P., & Liu, H.-L. (2020). Gateway to Outdoors: Partnership and Programming of Outdoor Education Centers in Urban Areas. Education Sciences, 10(11), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110340