Abstract

Song is a regular part of the lives of the little ones, from the family environment to school, where it becomes one of the most used tools in early childhood education due to its educational potential. Therefore, it is important to analyze in detail the content of the songs listened to by the youngest. This research starts with the hypothesis that children at an increasingly premature age listen to and play songs with sexist content, which may affect their future behavior. To confirm or refute it, a mixed methodology was used, using the questionnaire as instruments applied to 116 parents from 4 educational centers in A Coruña, and interviewing 7 teachers. The results indicate that schoolchildren are mainly exposed to musical genres not appropriate to their age, both in their family environment and in the classroom to a lesser extent, concluding that they listen to and play songs with sexist content, which may affect their future behaviors.

1. Introduction

In recent years, seeking an egalitarian society has been a constant concern, but it is a challenge that is difficult to achieve, and on which all social agents must undoubtedly collaborate. Society traditionally imposes on women very defined roles related to care, education of sons and daughters, food, and family—specific tasks in the private and domestic area. This is, of course, an important space, but a socially devalued one circumscribed under the “culture” of inferiority and female submission [1]. This made them historically receive less education than the men in their family. They had to try harder and they were not recognized on the same level as their peers, husbands, parents, etc. [2].

1.1. Historical Discrimination against Women

Undoubtedly, there is currently action that advocates reversing the situation [3], but the weight women have borne for so many years continues to take its toll and there are still gaps in a certain part of society that do not conceive that women’s capacities are equal to those of men. We still live in a world where discrimination reigns and is embedded in the deepest social codes of our society [4]. In this sense, the words of Rodríguez-Cao [5], translated by the authors, are clarifying when he affirms that

(…) female students obtain better results in what they study, but they continue to receive an implicit message that indicates their subordinate position in social, professional, and family ambits, contributing to the reproduction of patriarchal society (…) The possibility of choice offered by democratic society makes the differentiated socialization that girls and boys receive invisible (p. 74).

Indeed, it must be recognized that despite efforts, society remains uneven. People are treated differently based on their race, culture, social class, or sex in civilized countries. In the Spanish context, it should be noted that current legislation reflects the aspiration to equality between the sexes, and even the 1978 Constitution includes the need to prohibit any type of discrimination based on sex and introduces equal treatment and opportunities between women and men in all spheres of life.

However, despite the progress made and actions by the public authorities, equality between men and women in advanced societies has not been fully achieved. On many occasions, there are still differences in the distribution of household chores and childcare, access to positions of power, and the type of professions carried out by both sexes. Even today, attitudes and stereotypes that put women at a disadvantage are still in force [6]. One of the areas where we find many sexist elements is in music, specifically in many of the songs that society listens to and plays impassively [7], such as Latin musical styles like reggaeton, whose lyrics contain content directed, most of the time, towards perpetuating virile archetypes of power, dominance, and subordination over women, who, according to these messages, must live for and to please the desires of men [8].

In order to reduce the gap of this inequality, it is necessary for professionals from different scientific, educational, cultural, and administrative fields to promote openly anti-sexist action—individuals who question social hierarchies and follow ways of life that contribute to globalizing a social order committed to guaranteeing equality between women and men and, therefore, a more democratic and just 21st-century society [9]. In this sense, school is one of the fundamental pillars to achieving an egalitarian society that intends to eliminate any form of discrimination or subordination of one sex over another because of their differences, overcoming social inequalities and cultural hierarchies between men and women [10].

1.2. Song as a Transmitter of Values

Music accompanies us throughout our lives from the moment we are born, in all areas, often becoming the reflection of a certain society, since according to Mateos et al. [11] music “plays an important role in the construction of roles and stereotypes.” Therefore, due to the weight that music has in our lives, it is important to promote its value in the education of the youngest, so that as they grow older they naturally see music as an art that develops our cognitive, psychomotor, and affective-social abilities, brings us closer to the immediate reality, and fosters the formation of values, since, according to Garrido and González [12], “through its lyrics it can transmit certain values that shape our way of life,” because music plays an important role in the construction of roles and stereotypes.

Within the musical field, song is one of the most used tools, which even extends to other areas as a learning methodology to secure content or as a means of understanding the world around us. According to Giménez [13], it is the intersection of two very different worlds (music and lyrics) and constitutes a very useful element for the development of the person. It is not necessary to describe the importance of songs in the lives of students, as it is enough to observe children of all ages [14]. Undoubtedly, songs are one of the simplest ways of making and understanding music, since “they constitute models that are fixed in memory and facilitate later learning” [15]. It cannot be ignored that listening to music is one of the activities most valued and carried out by people [16].

In accordance with Barrios [17], Díaz [18], Díaz [19], and Giráldez and Pelegrín [20], among others, it is a primary formative element in education because it provides pleasure to learning. In this regard, Iturbe [21] agrees when he defends that music, and specifically songs, have great educational power, noting that half of his students admit to listening to music an average of 4 h a day. According to what he said (translated by the authors),

There is no subject at school with as much “workload” as music. And there is no educational program as effective as music. Music is a powerful instrument of socialization. Not only does it transmit a message, but it does so in an affective and effective way: The lyrics are mediated by music that opens our pores and lowers our defenses. The songs repeat messages that, by way of behavioral conditioning, can become part of our consciousness.

Certainly, it is common to use songs in the classroom as a powerful tool, taking advantage of their “great communicative capacity, potential and influence and their power to transfer messages” [22], hence the importance of the content of their lyrics. However, the youngest not only listen to songs in the classroom, but are immersed in an increasingly musical society, in which “the music that is heard today has changed its lyrics and messages in a radical way, for what has gone from romantic love to a more aggressive version of it” [23] (p. 14).

In the media songs are heard in which submissive and suffering women appear, an opinion that coincides with Ana Cano [11] when she states (translated by the authors) that what some genres transmit, like reggaeton,

it is a super strong indication of hypersexualization […] it endangers the sexual safety of many girls, who consume it, and in reality it is not always due to lack of access to communication, but because of the excess of support and exposure to this type of music.

In this regard, Carballo [24] assures that currently most of the songs most demanded by society include in their lyrics sexism, violence, and stereotypes that place women in social inequality, in some cases even justifying and promoting the appearance of this type of violence against women: “what is interesting is to show that in this phenomenon of symbolic violence, one of the mechanisms is to devalue the image of women through different forms of representation.”

2. Methodology

Scientific research is characterized among many aspects by its objectivity, empiricism, monitoring of the scientific method, and the establishment of a series of norms/laws that will be scientifically accepted as long as the contrary is not proven [25]. With this praxis, the reality regarding a question is investigated by means of analysis in the most trustworthy possible way. Methodology is understood as the “set of methods that are followed in a scientific investigation or in a doctrinal exposition” [26]. Methodology is one of the vital aspects of research work, since it can determine the achievement of the results or conclusions in an investigation regardless of the quality of the hypothesis and the established sample.

2.1. Objectives

This research starts from the hypothesis that children at an increasingly premature age listen to and plays songs with sexist content, which may affect their future behavior. To confirm or refute this hypothesis, the following objectives were set:

- To know the influence that new musical genres have within the family and school environments of children in pre-primary school education.

- To find out in which context children learn new musical genres.

- To find out the perception of parents regarding the possible impact of these genres on their children.

- To find out teachers’ perceptions of the possible repercussions of these genres on their children.

2.2. Design of the Research

To carry out this research, a mixed methodology based on the use of quantitative and qualitative research approaches was used. To do so, the most appropriate data collection techniques were selected to access the necessary information in order to respond to the targets pursued.

First, a sample was taken as a representation of the whole, with which, by analyzing the information collected and systematizing the data, the aim was to clarify the hypothesis by emphasizing the objectivity of scientific research [27,28].

2.3. Questionnaire

In this research, the methodological instrument used was the questionnaire. Following [29], it can be defined as “a technique that uses a set of standardized research procedures by means of which a series of data is collected and analyzed from a sample of cases representative of a broader population or universe, from the that it is intended to explore a series of characteristics.” The questionnaire was intended to measure a series of variables and feelings in the family environment of early childhood students, taking as a reference the Music@Home questionnaire [30]. This collecting data tool combines dichotomous (yes/no) questions with Likert scale ones (variables 1–5, with 1 being “totally disagree,” 2 “disagree,” 3 “neither agree nor disagree,” 4 “agree,” and 5 “totally agree”).

The questionnaire, aimed at parents of boys and girls from early childhood education centers in the Autonomous Community of Galicia and accessed online, was made up of 20 items, preceded by a first part with five demographic questions on sex, age, number of children, their age, and place of residence.

The second part asked about the type of music they expose their children to, musical styles they listen to at school, children’s liking of current songs, and the influence of the lyrics.

In order to provide the tool, teachers at the four centers were contacted by telephone and helped connect us with the parents of the students. Afterwards, the questionnaire was sent via e-mail to all the participants.

The analysis of the data obtained was carried out using the statistical program Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. It was chosen due to the fact that, despite being a program to carry out quantitative analyses, value labels can also be added and qualitative data parameterized in a simple way in order to develop an effective analysis. In this way, the data was structured according to the questions and different statistical analyses were carried out on them (mode, median, mean, etc.). Subsequently, links were established between some of the questions to find correlations that would help achieve the objectives of the investigation. Finally, a reliability analysis of this survey was also carried out, in which high reliability was verified according to Cronbach’s alpha.

As a complement to this research and after carrying out the analysis of the data from the questionnaires, a second collection of information was carried out via an interview methodological technique, which was included based on its double function:

- (a)

- To use it as described by Tuckman (1972) cited by Cohén and Manion [31], where it will serve as an instrument to obtain information regarding the objectives of the research:By providing access to what is inside a person’s mind, it makes possible to measure what a person knows (knowledge and information), what a person likes or dislikes (values and preferences), and what a person thinks (attitudes and beliefs).

- (b)

- As a complement to other research methods. In relation to this function, Kerlinger [32] assures that it could be used to track unexpected results, to validate other methods, or to delve into certain aspects related to the motivations that the respondents may have and that were not sufficiently defined after the use of other investigative techniques.

Indeed, the qualitative methodology allows us to understand and interpret social reality. It is also very helpful to see the relationship people have with their environment, how their experiences influence their lives, and the meaning they give them. The qualitative approach is therefore the most appropriate when what we seek is to understand the meaning that the subjects give to the social and educational experiences that they have [33]. To achieve this, it is essential to make a good selection of informants. In this study, the criteria of Patton [34] was used for the selection and the criterion of critical cases was applied—“the selection of critical cases points to those where the relationships to be studied become especially clear” [35]—to those to whom the objective of this study was explained, in addition to establishing a verbal confidentiality agreement, according to Cobos [36].

The recording of the interviews was carried out in a reliable way and respecting the criteria of stylistic literalism [37], which allowed the rigor of the information obtained to be maintained. They were subsequently transcribed and sent to the informants for validation before proceeding with the analysis.

2.4. Sample

This part required careful preparation prior to data collection. Based on the population, which is understood as a set of people or objects that have characteristics in common in a given place and time, we find the sample, this being a subset that represents the population. An improper choice can lead to inevitable errors in the results.

While 390 parents from 4 public educational centers were invited to participate in the study, only 116 contributed. On the other hand, the sample that assented to interviews coincided with the actual participants: 7 people.

A total of 100% of the questionnaire participants resided in the province of A Coruña, with 80% of them women and 20% men aged between 27 and 46 years, with the majority ranging between 30 and 40 years. The number of children of the parents was between 1 and 4, with families with 1 or 2 children predominating. The age range of the boys and girls was between 3 and 6 years, and in more than 60% of cases with siblings, they were the oldest.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Questionnaire Results

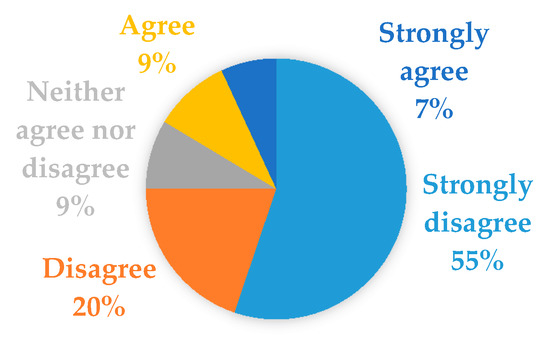

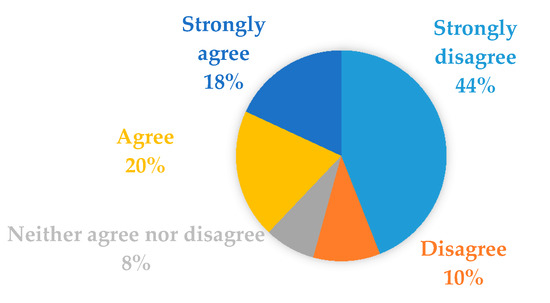

First, the data collected through the questionnaire is described and analyzed. As can be seen in Figure 1, only 7% of the subjects claimed to exclusively expose their son or daughter to children’s music of the 116 subjects in the sample, while 75% disagreed or completely disagreed with this statement, thereby affirming that their son or daughter listens to more musical genres.

Figure 1.

I only expose my child to children’s music.

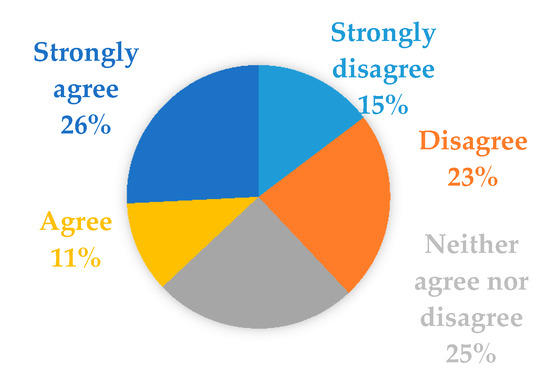

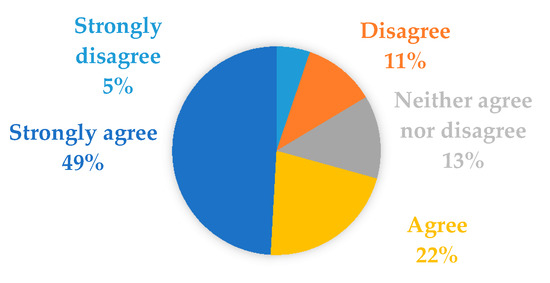

Next, it was asked if they considered that the music their child listens to in their environment was appropriate for their age, to which 37% answered affirmatively, while 38% considered that the music their children listen to was not appropriate (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

I consider the music my child listens to appropriate.

To the question of whether they preferred to sing children’s songs to their children, the answer was emphatic: 57% said that they do, while 33% do not.

When analyzing the data from question 9, 64% of the participants in the research assured that their children like to listen to children’s music, popular music, or traditional music, while 19% disagreed with this statement.

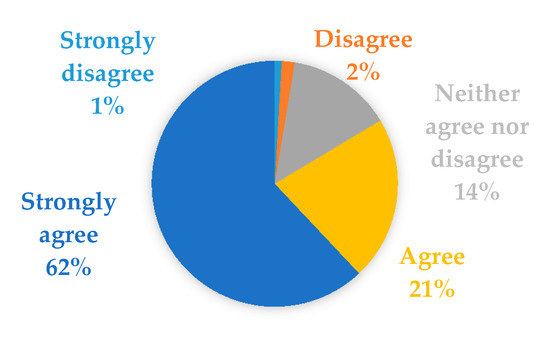

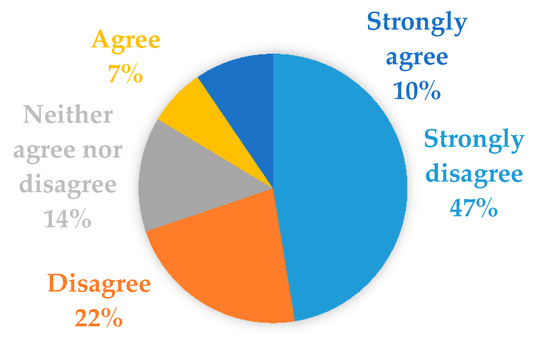

Figure 3 shows that 83.6% of the sample considered it important to know the content of the lyrics of the songs that their children listen to or sing in order to make a selection.

Figure 3.

I select the songs my child listens to/sings, taking into account the content of the lyrics.

Question 11 asked specifically about whether their children like to sing or dance to current songs, to which 78% answered affirmatively, despite the fact that the lyrics are not appropriate for their age. Only 8% completely disagreed with this statement (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

My child likes to sing or dance to current songs, even if the lyrics are not appropriate for their age.

In line with the previous question, it was asked whether the youngest in the house are exposed to current styles, such as reggaeton, trap, electronic music, etc. Only 54% of the sample responded negatively, and 38% of respondents acknowledged that their children are in contact with this type of music (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

My child is exposed at home to musical styles such as reggaeton, trap, electronic music, etc.

A total of 71% considered the lyrics of current music to influence their children’s vocabulary, while 16% disagreed with this statement (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

I believe that the lyrics of today’s music influence my child’s vocabulary.

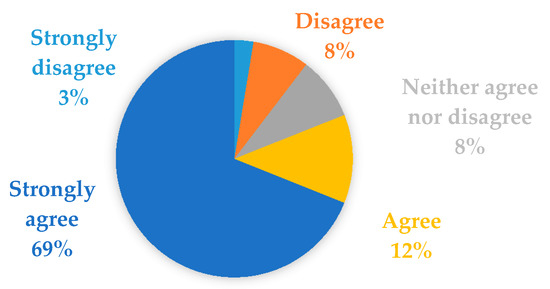

As can be seen in Figure 7, when it comes to allowing children to view music videos of songs from genres such as reggaeton or trap, the answer was forceful: 69% declared that they do not allow it, compared to 17% who do.

Figure 7.

I allow my child to view music videos of songs from genres such as reggaeton or trap.

Regarding the opinion of whether children should listen to all kinds of musical genres, 64% of the subjects considered that they should, compared to 24% who thought that they should not.

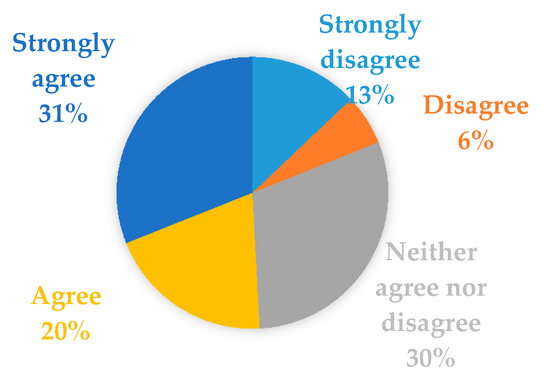

Next, it was asked if they considered new musical styles to have a negative impact on the education of their children, to which 51% responded affirmatively, compared to only 19% who considered that it does not. It is striking that 30% did not take a position in this regard (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

New musical styles have a negative impact on my child’s education.

In line with this, 61% considered that their children should not listen to songs with inappropriate lyrics, with only 12% being in favor. Again, a high percentage (27%) took no position regarding this question.

When question 19 asked if their child hums song lyrics that are not appropriate for their age, 77% said they do, compared to 7% that said they do not. A total of 16% had answers in the middle.

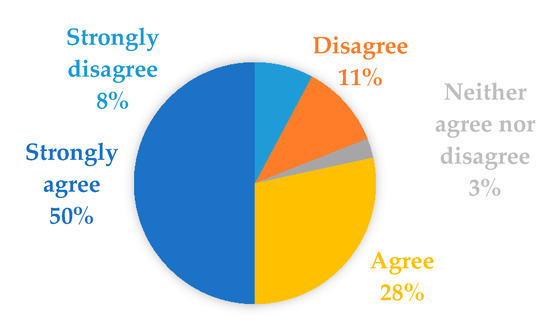

Finally, regarding the question “If you knew that the influence of current music could affect your child’s development, would you take measures to prevent it?” 81% affirmed that they would, compared to 11% who disagreed with this statement (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

If you knew that the influence of today’s music could affect your child’s development, would you take measures to prevent it?

3.2. Analysis of the Results of the Interviews

In order to understand certain aspects reflected therein, the research was completed with interviews with 7 teachers of early childhood education from the 4 educational centers in which the questionnaire was conducted, with ages ranging from 30 and 61 years old and extensive teaching experience. These were recorded and transcribed respecting the criterion of stylistic literalism [37]. To perform the analysis, the information was coded according to the categories presented below:

3.2.1. Musical Genres to Which They Expose Their Students

Most of the teachers interviewed affirmed that they expose their students to different styles of music, because as interviewee 2 affirmed, they expose their students “to all kinds of music”. Only two affirmed that they present their students with only children’s music, traditional music, or classical music (interviewees 6 and 7).

3.2.2. Most Appropriate Genres for Pre-Primary School Education

In line with the previous answers, in general the teachers considered that any genre was suitable for this educational stage, although it should be noted that interviewee 1 pointed out that students “should get used to listening to all kinds of music, especially those they do not usually listen to at home (classical)”. It should be noted that interviewee 7 was aware of the problem since she pointed out that “all music can be appropriate, reviewing the lyrics in advance”.

3.2.3. Music Listened to by Little Ones outside the Classroom

When we asked the teachers if they considered the music that the children listen to in their environment ideal, five of the subjects considered that it is not always the most appropriate. As interviewee 1 pointed out, “Not very. Normally, because of what they ask for, they listen to a lot of reggaeton, which is not the most appropriate, not because of the rhythm, but because of the lyrics.” It is worth noting the answer of the interviewee 3: “The broader the music, the better; everything is OK.”

3.2.4. Exposure in the Classroom to Current Music

Four of the seven teachers assured that they use current musical genres at some point in the school year with some frequency, such as when there is a party (carnival, birthdays), listening to the oldest children in the courtyard, and even in the music inside and outside the school: “When there is a party and we play music in the classroom to dance to for a while, I do play current music, pop, or reggaeton” (interviewee 1). On the contrary, three teachers affirmed that the students are not exposed at any time of the day to this type of musical genre.

3.2.5. Impact of New Styles on Education

When asked if they believe that new musical styles have a negative impact on the education of children of this age, six of the teachers interviewed confirmed that they believe that they do not affect their education, with respondent 1 alleging:

We must teach them to be critical from a young age. Listening to music should be like a movie or telling a story to children. If you analyze the meaning or the moment in which you put on each type of music, it should not have a negative impact.

Another teacher clarified that “at advanced ages they can be critical and analyze the lyrics, while the little ones would have no problem.” The only teacher who thought that they do have a negative impact alleged that in order to use them it would be necessary to “prepare them first in order to be able to analyze and be critical of certain lyrics” (interviewee 7).

3.2.6. Humming Current Songs in the Classroom

In relation to the question of whether they observed a student humming lyrics not suitable for their age from songs currently popular in society, all the interviewees agreed on the affirmative answer, with the most common songs that they heard being “Despacito” by Luis Fonsi, “Échame la culpa” by Luis Fonsi and Demi Lovato, “Chantaje” by Shakira, “Dame tu cosita”, and “Mayores” by Becky G, “Dura” by Daddy Yankee, and even “Gangnam Style”, to which most know the complete dance. In this regard, the interviewees reported that the children assure that they know these songs for various reasons: “My father sings this song to me”, “I know the song ‘Dame tu cosita’ by heart”, “I have it in my car”, “Mom puts it on at home”, “This is the music I like”, etc.

3.2.7. Importance of Knowing the Content of the Lyrics

When asked if they consider it important to know the content of the lyrics of the songs when choosing the music for their students, they agreed that it should be so, claiming that for this reason, “When I choose, I try to make the lyrics the most suitable possible, but boys and girls are in society and they will listen to everything. Therefore, my opinion is that they must face all kinds of genres” (interviewee 3).

Finally, we questioned the teachers interviewed about whether they would take respectful measures in the classroom if they knew that the influence of current music could affect the development of their students, to which all agreed that they would.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this research was to find out the influence that new musical genres have on children in early childhood education, given the concern that they are unduly exposed to songs with a marked sexist character. After analyzing the data, it is worrying that the percentage of parents (7%) and teachers who claim to expose the youngest exclusively to children’s music is minimal, since as Díaz indicates [38], it is important to bear in mind that parents and educators play a very important role in enhancing and developing the capacities for expression and communication needs that all children show from birth, and it is a great task to be prepared to be able to do the work of being a guide and educator in musical sensitivity. Along these lines, Arévalo [39] states that “children’s songs form the basis of a musical education class, especially in the first levels, where the beginning of singing is done in a playful way, in addition to reflecting the spirit of the youngest.” This data would not be negative if they were exposed to cultural music or musical genres without sexist content.

Once it was shown that the most popular musical styles are not the most appropriate for children, exposure in homes to musical styles such as reggaeton, trap, electronic music, etc. was studied in depth. More than half of the parents denied that they sing in the family, which was contradicted by the answers they offered to other questions and with the statements from the teachers, who said that the children declare that family members are the main people responsible for them listening to this type of music. However, schools also participate in the dissemination of these musical styles, even at specific moments such as celebrations, anniversaries, or festivities at school, ignoring that the lyrics usually contain messages that marginalize or denigrate women. It is surprising that the majority of the participating families were not aware of the type of music to which they subject their children, and even more amazing is that the educational environment itself contributes to spreading inappropriate songs with clearly discriminatory content towards women. According to [40], the references and interests of the boys and girls of our society undergo changes at the same speed as their environment changes.

Despite this, the parents and teachers of the youngest in A Coruña recognize that they listen to and sing songs that are not in accordance with their ages due to the content of the lyrics, which may negatively affect their perception of the equality of women. It is very important to know the content of the song lyrics before playing them at home or in the classroom to avoid the social inequality referred to by [24].

The same happens when they are allowed to view music videos of reggaeton or trap songs, since they should not see them due to the violence of their images. According to Vera [41], “at present, boys and girls are more television viewers than students. Television is increasingly part of their reference universe, and this causes changes in the attitude of boys and girls.” In line with this, Chao-Fernández e al. [42] and Santiago and Miras as quoted in [43] point out that the songs that boys and girls sing spontaneously often belong to some television series or popular song, which can bring about the following consequences:

- Showing the influence that media has on the youngest.

- Lack of imagination to invent games and songs and loss of originality and expression in boys and girls.

- Making little effort in school to try to preserve the cultural heritage of our ancestors.

- The progressive impoverishment of our language.

It should be added that this type of music brings with it the construction of roles and stereotypes [11], being in this case discriminatory, violent, and sexist.

5. Conclusions

After analyzing the results of this research, it can be affirmed that the hypothesis that children at an increasingly premature age listen to and play songs with sexist content has been confirmed, which may have an impact on their future behavior. This is confirmed based on the answers given to the proposed objectives, which are confirmed by the conclusions shown below.

Concerning the first objective regarding knowing the influence that new musical genres have within the family and school environment of children in early childhood education, it is concluded that a high percentage of children of these ages are exposed to musical styles that do not include children’s or traditional music, and genres that are not appropriate for their ages largely due to the content of their lyrics.

Regarding the second objective, which was to know in which context the child learns new musical genres, it is concluded that they primarily access these songs in the family environment, although schools also contributes to children learning them. This is worrying, since both families and teachers recognize that these types of songs are not suitable for children in particular, nor for society in general, and yet they do not put a stop to this situation.

Regarding the objective of finding out the perception of parents of the possible impact of these genres on their children, it can be concluded that they are aware that the content of the lyrics they listen to can influence their vocabulary, which is in line with the teachers’ perceptions, thus responding to the fourth objective. Fortunately, most of the younger schoolchildren who listen to and dance to these lyrics do not get the real message, but there is a risk that they are internalizing their content and that this affects their future behavior, especially when the songs are accompanied by the corresponding videos. It is likely that if the family members were really aware that the contents of the lyrics they hear can influence both the vocabulary and the behavior and values of their children, they would try to change habits. In short, we confirm that it is worrying that, despite the work to bring awareness to sexual discrimination, these songs with evident discriminatory content continue to be allowed, and that society in general is not aware that playing them in front of the youngest could lead to a perception of the attitudes reflected in these songs in the future.

Finally, it is necessary to point out the limitations of this study. It was not possible to access a larger sample because this study was conducted during confinement. In this regard, it is necessary to highlight that there are very few studies on this topic focused on the early childhood education stage, since most of the research focuses on other age ranges. It is therefore important in the future to continue deepening and expanding the study sample in order to reinforce the results obtained, which would increase reliability and credibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.-F., A.C.-F., and C.L.-C.; Methodology, software investigation, and resources, A.C.-F., C.L.-C., and R.C.-F.; Formal analysis, A.C.-F., R.C.-F., and C.L.-C.; Writing of the manuscript. R.C.-F., C.L.-C., and A.C.-F.; Supervision project, A.C.-F., R.C.-F., and C.L.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cobo, R. Repensando la democracia: Mujeres y ciudadanía. In Educar en la Ciudadanía. Perspectivas Feministas, 1st ed.; Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mato-Vázquez, D.; Chao-Fernández, R.; Suárez-Brandariz, R. Las Mujeres en las Artes y en las Ciencias. Reflexiones y Testimonios; Servicio de Publicaciones de la UDC: A Coruña, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, M. La masculinidad hoy: Un género obsoleto. VV.AA. Actas del Congreso Internacional e interdisciplinar Mundos de Mujeres Women’s Worlds 2008. In La Igualdad no es una Utopía. Nuevas Fronteras: Avances y Desafíos; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, C. Género y Cultura Escolar; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cao, L. Muller e Superdotación. In As Mulleres nas Artes e nas Ciencia. Reflexións e Testemuñas, 1st ed.; Mato-Vázquez, D., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la UDC: A Coruña, Spain, 2013; pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, M.A. La Ciudadanía y los Derechos de Mujeres y Hombres; Dirección General de la Mujer, Gobierno de Cantabria: Santander, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-de-Luna, E.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. Música y género: Análisis de una muestra de canciones populares. Comunicar 2002, 18, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Carrión, M. Música y Género: Estereotipos Sexuales a Través de la Música. 2011. Available online: http://recursostic.educacion.es/artes/rem/web/index.php/ca/curriculo-musical/item/360-m%C3%BAsica-y-g%C3%A9nero-estereotipos-sexuales-a-trav%C3%A9s-de-la-m%C3%BAsica?tmpl=component&print=1 (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Iglesias, A. Xénero, Igualdade e Cidadanía: O Compromiso das Universidades, 1st ed.; Mato-Vázquez, D., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la UDC: A Coruña, Spain, 2013; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, M.E. Coeducación: La unión perfecta de lenguaje y género. Rev. Semest. Iniciación Investig. Filol. 2011, 6, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, C.; Pita, A.; Vélez, M.; Cedeño, R.; Ruiz, J. Un análisis de la violencia y el sexismo desde el imaginario musical ecuatoriano de la región Costa. Rev. Comun. SEECI 2015, 38, 225–261. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, E.; González, E.M. Sexismo en las Canciones Disney; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, T. El uso pedagógico de las canciones. Eufonía 1997, 6, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Malbrán, S.; García, E. Lenguaje musical y didáctica: Tiempo y estructura métrica. In Fundamentos Musicales y Didácticos en Educación Infantil, 1st ed.; Riaño, M.E., Ed.; Publican: Santander, Spain, 2010; pp. 109–153. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.; Arriaga, C. Espacio y Tiempo. Revista de Ciencias Humanas 2013, 27, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Megías, I.; Rodríguez, E. Jóvenes Entre Sonidos: Hábitos, Gustos y Referencias Musicales; Instituto de la Juventud: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, P. Una propuesta de investigación: La música de tradición oral en un núcleo rural y su aplicación didáctica. Rev. Lista Electrónica Música Educación 2000, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M. El valor educativo de la canción en los juegos infantiles. Música Arte Proceso. 1999, 7, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M. Una educación musical por la diversidad y para la integración cultural. In L´activitat Docente. Intervenciò, Innovaciò, Intestigaciò, 1st ed.; Vallès, J., Ed.; Documenta Universitaria: Girona, Spain, 2011; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Giráldez Hayes, A.; Pelegrín, G. Otros Pueblos, Otras Culturas. Música y Juegos del Mundo; Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Iturbe, B. Sexo, sexismo, música y amor. Padres Maest. 2009, 325, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Colomo, E.; De Oña, J.M.; Vera, J. Análisis pedagógico de los valores transmitidos en las letras de las canciones con más impacto en 2010. Rev. Cienc. Educ. 2013, 233, 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C. El Sexismo a Través de la Música y su Impacto en el Desarrollo de la Identidad Infantil; Universitat Jaume I: Castelló, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, P. Música y violencia simbólica. Rev. Fac. Trab. Soc. UPB 2006, 22, 28–43. Available online: https://revistas.upb.edu.co/index.php/trabajosocial/article/view/256 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Ñaupas, H. Método de la Investigación: Cuantitativa-Cualitativa y Redacción de la Tesis; Ediciones de la U: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. Diccionario de la Lengua Española; Madrid, España, 2018, 23rd ed. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/?id=P7eTCPD (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Canales, M. Metodologías de Investigación Social; Lom Ediciones: Santiago, España, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Gortari, E. Métodos y técnicas. In El Método de las Ciencias. Nociones Preliminares, 1st ed.; De Gortari, E., Ed.; Editorial Grijalbo: México, México, 1979; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- García Ferrando, M. La encuesta. In El Análisis de la Realidad Social. Métodos y Técnicas de Investigación, 1st ed.; García, M., Ed.; Alianza Universidad Textos: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Politimou, N.; Stewart, L.; Müllensiefen, D.; Franco, F. A novel instrument to assess the home musical environment in the early years. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Métodos de Investigación Educativa; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Investigación del Comportamiento, Técnicas y Metodología; Interamericana: México, México, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, J.; LeCompte, M. Etnografía y Diseño Cualitativo en Investigación Educativa; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. La Gestión de la Calidad en Investigación Cualitativa; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cobos, A. La Construcción del Perfil Profesional de Orientador y de Orientadora. Estudio Cualitativo Basado en la Opinión de sus Protagonistas en Málaga. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2010. Available online: http://www.biblioteca.uma.es/bbldoc/tesisuma/17968501.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Pujadas, J. El método biográfico y los géneros de la memoria. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 2000, 9, 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M. La educación musical en la etapa 0–6 años. Rev. Electron. LEEME Lista Electrónica Eur. Música Educ. 2004, 14, 1–6. Available online: https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/LEEME/article/view/9750/9184 (accessed on 26 September 2019).

- Arévalo, A. Importancia del folklore musical como práctica educativa. Electron. LEEME Lista Electrónica Eur. Música Educ. 2009, 23, 1–14. Available online: http://musica.rediris.es/leeme/revista/arevalo09.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2019).

- Pérez-Moreno, J.; Reverté-Folch, L. Las actividades musicales preferidas de la voz de los propios niños y niñas de cuatro años. Un estudio de caso. Rev. Electrónica LEEME Electron. J. Music Educ. 2019, 43, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, A.L. Televisión y espectadores. Comunicar 2005, 25, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chao-Fernández, R.; Gisbert Caudeli, V.; Chao-Fernández, A. Contribución a la conservación del patrimonio musical en educación Primaria. Estudio de caso en Galicia en 2003 y 2019. Rev. Electrónica LEEME 2020, 45, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual Mejía, P. Didáctica de la Música en Educación Infantil; Pearson Pentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).