Abstract

This explorative, qualitative study examines the use and effectiveness of resources of multilinguality, with particular regard to the development of causal links in geography classes. Contentual and linguistic strategies of multilingual pupils in creating causal links were collected and evaluated systematically. This was done by means of a qualitative content analysis of oral, cooperative lesson sequences. A model on how to deal with multilingual, systemic learning settings is presented as a resulting hypothesis.

1. Introduction

Approximately 30% of students in Germany possess a migrant background and non-German family language (e.g., Turkish or Russian) [1] (p. 93). The effect is a heterogeneity in experiences, intercultural backgrounds and spoken languages in families and schools—with all the potential connected hereto [2,3,4]. This lingual and cultural heterogeneity is currently being considered in subject teaching in no more than a negligible manner. Multilingual learning opportunities offer both cross-curricular, everyday life-integrating [5] and subject-specific language support [6]. Furthermore, the research field of multilinguality is of high importance for around 140 German schools abroad, with their approximately 84,000 students, as well as around 1100 DSD schools (schools offering the German Language Diploma) with around 368,000 students [7] (pp. 1–6). Especially since the teaching of geographical content in the context of teaching German as a foreign language (DaF) or in subject-related learning at German schools abroad takes place in multilingual realities, it is highly interesting to find out what effects multilingual learning settings have in these learning situations. In Germany as well, language promotion in geography classes has become a relevant research field in recent years [8,9,10,11]. Most publications attend to language-sensitive teaching [12,13,14]. There is, however, still a lack of research into the potential of multilinguality for teaching geography [15].

Resources of multilinguality have so far been ignored when organizing, planning and conducting geography lessons [16]. Therefore, this article examines the effects and potential of the presence of more than two languages on functional learning in geography classes. The reference framework for this study is teaching causal links, based on geographical content and technical language within the German school system abroad. The ability to make causal links, which is particularly important in geography lessons, is one of our “most central cognitive competences” [17] (p. 1) that enables pupils to understand the complex system of causality (e.g., the phenomena of climate change) in our world. According to the authors, the assumption is obvious that multilingual learning settings support students in fulfilling the various contentual and linguistic challenges occurring when creating causal links.

Due to the increased language awareness [18,19] and other cognitive transfer strategies [20] of multilingual learners, however, it could offer enormous potential for teaching systemic thought processes [21,22] in geography lessons [23] (p. 4), especially with regard to the development and verbalization of causal links. At the core of the analysis are linguistic strategies of students (n = 10) for developing contentual causal connections for the exemplified topic of tourism. The qualitative, explorative study was carried out in May 2019 in Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan).

The central research questions are:

- What is the influence of the particular strategies and resources of multilingual students on the contentual understanding of a topic in the classroom?

- What effect do multilingual strategies in cooperative learning methods have on the creation of causal speech acts?

Following a brief presentation of the current state of research on language-sensitive geography teaching, the concept of multilinguality is introduced. Then, linguistic and cognitive resources of multilingual students are identified based on existing research results. Proceeding from this theoretical basis, the empirical results are presented and discussed. Finally, ideas for multilingual geography teaching are developed.

2. Complex Language Brings about Complex Thinking?

The starting point for this study is the assumption that establishing multilingual geography classes may be a constructive contribution to subject-specific language promotion, in particular for promoting geography-related, causal speech acts. Thus, the significance of language and language awareness for learning geography will be depicted in the following.

2.1. Significance of Language and Language Awareness for the Subject of Geography

Language is the medium, object and target of learning at school [24] (p. 32). Language has several central functions in learning. As a medium, language enables communication and interaction (communicative function). Furthermore, language is the basis for learning content and thus for the development of skills and desired competences (cognitive function). Language is also an object or a tool of learning (epistemic function), both to tap into subject-related knowledge resources and to master subject-related language production [13] (pp. 10–15), [25] (pp. 10–11). In addition, language is a medium for assessing students’ performance [26] (p. 13). Due to this central importance of language, the topic of subject-related language promotion or language-sensitive specialist teaching has received increased attention in recent years, including in geography lessons. Budke & Weiss [27] (p. 127) define language-sensitive geography teaching as teaching “which considers the subject-specific linguistic requirements for understanding and answering geographic questions in the classroom, based on students’ preconditions.” (translated).

The necessary subject-related language competences are termed subject-related language register [9] (p. 224). Language promotion is supposed to happen at the level of words (e.g., technical terms as elements of the system), at the level of sentences (e.g., expressing a causal link using conditional clauses) and at the textual level (e.g., when reading technical texts). According to Budke & Kuckuck [28] (p. 22), this kind of language promotion in geography classes leads to the following academic language competences (CALP, [29]): a. informational competence, b. knowledge and application of technical terms/language, c. competence to perform communicative actions, e.g., developing an argument or presenting content, d. discourse competence, and e. metacognitive skills which lead to developing a specific language awareness. Strategies to support language activities may, for example, be scaffolds [30] (p. 35) that, e.g., reduce language barriers when developing causal links [31] (pp. 31–33). The aim of subject-related language promotion is the reduction of language barriers for acquiring knowledge and the creation of subject-related language awareness.

So far, aspects of multilingual didactics have predominantly been researched in foreign language classes [3,32,33] or bilingual subject classes [10]. The studies by Weissenburg [34,35] form an exception, where multilinguality in geography was explicitly examined. The intra- and intersubjective potential of spatial learning in the context of multilingual, sensitive geography teaching were worked out exemplarily by the author. In their empirical study, Repplinger & Budke [16] examined experiences and language use by multilingual students in both classroom and non-classroom contexts. They did not only work out the positive anticipations of monolingual German-speaking students but also those of the multilingual ones regarding multilingual lessons—potentially resulting in increased motivation, raised interest and more active participation. Furthermore, students have a very favorable attitude towards using authentic materials and towards an expected mutual intercultural gain. Budke & Maier [15] have been able to show that the majority of surveyed students with multilingual backgrounds had been unable to apply their proper language skills in their school days.

2.2. Metacognition and Language Awareness

Language awareness and metacognition exert great effects on both the learning process and learning success [36] (pp. 95–99). Language awareness is defined “as explicit knowledge about language and as a conscious perception and sensitivity during language acquisition, lessons and use” (ALA, 2012, quoted after [37] (p. 7)). For the formation of language awareness, an awareness has to be raised for declarative (i.e., contentual) and procedural (i.e., strategic) knowledge [38] (p. 255). By means of metacognition, students make their own learning processes (and language) an object of their thinking. Thus, they learn to monitor and control them [39] (p. 218). Metacognitive principles and phases in the classroom perform a central role in the development of language awareness and thus technical linguistic skills [40] (p. 14).

Language awareness is therefore of central importance for language promotion in geography lessons [10] (p. 77), [12] (pp. 83–97). Improved language skills allow and enhance content-oriented learning processes [41] (p. 11). More sophisticated language skills furthermore permit more complex thought processes and lead to more complex language production [13] (p. 15). Language awareness is also a crucial element when it comes to detecting language deficits and defining development goals. It is important for learning and applying strategies to overcome shortcomings [40] (p. 19).

Hauska [40] and Jessner [18,42] have been able to give evidence that multilinguality exerts a positive influence on the development of language awareness and metacognitive strategies. This positive finding is particularly relevant for the presented study. It can be assumed that by deliberately choosing and comparing languages, by using multilingual material or by carrying out multilingual teaching sequences, the resources of multilingual learners are activated. Multilingual geography teaching could thus have a reinforcing effect on the development of language awareness [18] (pp. 24–25). Multilinguality, language awareness and metacognitive skills are mutually strongly interconnected, positively affecting the development of causal language competences.

3. Complex Systems and Their Causality

Human–environment systems and their causal interrelations are fundamental issues in geography lessons. Insight into the contentual and linguistic peculiarities of these systems is a precondition for the targeted development of (multilingual) promotion strategies in the context of causal links. This happens to initiate higher degrees of geographical systemic competences (modeled after Mehren et al. [22] (p. 6)).

3.1. Complex Systems and Causality as Learning Objectives in the Geography Classroom

A central topic in geography lessons is complex systems [43] (p. 10). This comprises, for example, the totality of relations and phenomena connected with traveling in the context of an integrated tourism model [44] (p. 3, p. 51). According to Müller [45] (pp. 37–39), a complex system is constituted by elements (e.g., players, like tourists or travel agencies), the degree of connectedness (e.g., system organization, intensity of touristic exploitation) and the space–time dynamics (e.g., temporal and spatial development of organizational processes, tourist figures, touristic offers). The starting point for analyzing a system can be a complex, geographical problem, e.g., the observation that a human–environment system is fragile, not sustainable or dysfunctional. One example is the destruction of the ecosystem by the overexploitation of resources through tourism. The target might be to analyze the causes of destruction and overexploitation and to examine the connections between touristic potential and touristic exploitation in order to understand the consequences. This analysis puts students in a position to define an operational goal (e.g., environmental protection) and develop solution strategies (e.g., sustainable forms of tourism) to alter the system according to these targets. Frequently, an important object for analysis in complex systems is causalities, or more specifically, causal links.

Causality is a functional relation between a cause and an effect. This relation bears three aspects: (a) its effectiveness, i.e., the potential to evoke a certain effect or the very causing (e.g., spatial changes through tourists, as a result of effects), (b) the effecting (e.g., players, geological factors) and (c) the interdependencies of cause and effect (e.g., motifs and interests of players). An effect cannot be placed before its cause in time [46] (p. 290). Luhmann [47] sees causality positioned within a system which only appears in dynamic (disbalanced) systems. Moreover, causality is always self-referential, i.e., it exclusively refers to relations between elements in the same system. The attribution of cause and effect happens, however, from outside by an observer [47,48] (p. 91). A causal scheme is valid only for one system (“limitational”). In geography lessons, causal thinking is an operation which often means concluding backwards from observable effects (e.g., decline of species, pollution) to their causes (e.g., lifestyles, touristic trends, consumer behavior). Subsequently, the relation (e.g., more tourists, increased resource consumption) is reconstructed logically. These operational components are then expressed/converted in written or oral language [49] (p. 98).

3.2. Linguistic Features of Causal Links in the Geography Classroom

The verbalization of causal thinking requires a specific content-related language register. This is in each case bound to the specific situation of its use, which is predefined by the geographic content and its inherent structure [9] (p. 242). Thereby, three distinct levels determine a causal connection from a linguistic (and thus also geographic) point of view: real-world (geographic) relations, speaker’s assumptions and attitudes (subjective, mental spatial concepts) and the speech act situation (didactic space in the geography classroom; after Sweetser, [50]). A causal speech act in the geography classroom is commonly understood as a sentence made of technical terms, indicative verbs, main/subordinate clause constructions as well as conjunctions/adverbs/prepositions. These elements will be briefly presented in the following (Figure 1; [51] (pp. 20–22).

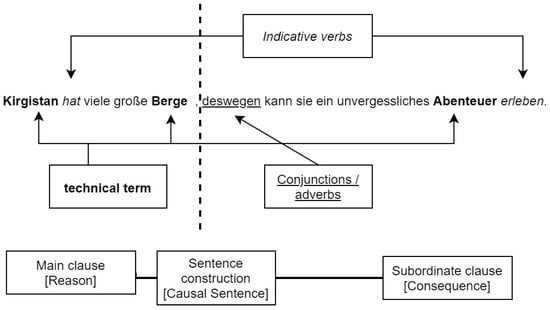

Figure 1.

Characteristics of causal speech acts.

Content-related geographical technical terms (e.g., “destination”) or phrases consisting of nouns and adjectives (e.g., “touristic potential”) mark the system elements and their spatial localization. Verb constructions (e.g., “reduce”, “require”) or adverbial phrases (e.g., “due to the high consumption…”) express the time, direction and intensity of the causal interdependence, thus characterizing the relations between the elements [52] (pp. 256–259), [53] (p. 108). Using adverbial clauses consisting of a main/subordinate clause construction allows the marking of cause and effect on the sentence level. Different sentence types feature specific (causal) attributes. Causal sentences allow a reason (“Why?”) to be connected with a consequence. Conditional sentences connect a reason with a condition (“Under which condition?”). Consecutive sentences connect a cause with a consequence [54] (p. 328). Less common are, for example, concessive sentences. The example given (Figure 1) is a causal sentence. The subordinate clause (therefore, she can experience an unforgettable adventure) has the function to define a consequence for the reason (Kyrgyzstan possesses many high mountains) in the main clause (carrier sentence) [55] (p. 378). Main and subordinate clause are introduced with a (causal) conjunction, subjunction or adverbs, e.g., “as” and “because”, “since”, “that’s why” (in the example Figure 1 with the adverb “because of this”). They express the dependence between cause and effect. They work as causal markers on a lexical level [52] (pp. 258–262). A successful causal speech act in a geographic sense is contentually and linguistically coherent. Linguistic coherence occurs where spatial, temporal and causal encoding allow a linguistic attribution of cause and effect [49] (p. 280). Contentual coherence means that this very linguistic attribution of a cause to an effect corresponds to the current state of geographical or scholarly knowledge.

4. Multilinguality—A Resource for Developing Causal Links?

Multilinguality or multilingualism is omnipresent, be it on Instagram or in popular music. The various forms of using more than one language permeate directly or indirectly every facet of human life, from multilingual social arrangements up to multilingual individuals [56] (p. 4).

4.1. Multilinguality—Characterization of An Everyday Phenomenon

In contrast to the term multilingualism, which is more commonly used in the current literature and focuses more on the acquisition process and the result of this process, the term multilinguality is used in this study. Multilinguality refers more to the individual, inner constructs of the speakers, their emotions, attitudes, preferences and mindsets [57] (pp. 15–24). In fact, there exists no unitary concept of multilinguality or multilingualism.

A rough differentiation is made between internal and external multilinguality [58] (pp. 345–346). Internal multilinguality, which this article focuses on, refers to individuals who use more than one language separately or in a mixing manner, at diverging degrees of competence [59] (p. 3). Several languages are connected interactively as an “internal multilinguality” in their cognitive system (“plurilingualism”, [60] (p. 214)). This implies, however, that individuals create many of their own variations of one or several languages [2] (p. 8). Lüdi and Nelde [61] (p. VIII) define multilinguality as “a repertoire which allows to satisfy everyday communication needs, both oral and written, in different situations and interchangingly in several languages.” Herdina und Jessner [62] explain the acquisition and the use of different languages in their “dynamic model of multilinguality (DMM)” in the following way: languages are understood as complex, interacting and adaptive systems, that interfere mutually and are additionally influenced by external factors [63] (p. 212). A multilingual individual disposes of the linguistic knowledge and the contextual/social experience to decide as to how and when a domain-specific language is appropriate in a given social situation [64] (p. 17). Beyond this, there are differences between types of multilinguality in relation to the age at the beginning of and its intensity in the course of the acquisition process.

Whether the acquisition process happens naturally or controlled, combined or coordinated, simultaneously or successively, also influences the development of internal multilinguality [65] (p. 19). Differences in the acquisition processes are causes for asymmetric competence levels. Müller et al. [66] explain these differences with a domain-specific development, based on the frequency of use, the appropriateness and the practicability. Therefore, multilingual speakers are able to communicate better or worse in different languages, depending on the situation, content and target group. Multilinguality is presented as a social situation in which, apart from the standard or national language, several languages are spoken [59] (p. 3). This can be designated as external multilinguality. Hu [60] (p. 214) describes external multilinguality as “additive coexistence of several languages in a society”; according to Gogolin [67] (p. 342), it is a “coexistence of one or several main communication languages”. This includes aspects of social and institutional multilinguality (e.g., several languages in governmental institutions, like schools; Garibova [68] (pp. 30–32)). Origin-related heterogeneity, spatially related language varieties and dialects generally determine the multilinguality of a society. A special variant of external multilinguality is diglossia.

4.2. Multilinguality—A Resource for the Development of Causal Links in the Geography Classroom?

Cook [69] brings up a multi-competence of multilingual learners that is expressed in a (a) lingual, (b) cognitive, (c) intercultural and (d) communicative dimension. Based on earlier studies, the following types of potential (cf. Figure 2) of this multi-competence can be identified for the acquisition of a technical language (here, causal speech acts):

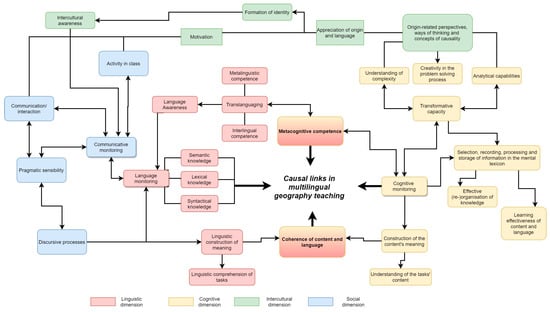

Figure 2.

Possible effects of multilingualism on the development of causal language actions (own presentation).

- (a)

- Jessner [42] (pp. 35–37) [18,70] explains the augmented speech act competence of multilingual learners by a raised metalinguistic and interlinguistic awareness. Other authors justify the linguistic competences of multilingual individuals through the concept of “translanguaging” [71,72] (p. 5). Translanguaging is the dynamic and functionally integrated use of different languages and language varieties. Predominantly, it is, however, a process of knowledge construction that goes beyond language(s) [20] (p. 15) (Figure 2: linguistic dimension). Both approaches refer to a linguistic and cognitive metasystem which, via permanent monitoring processes, enables multilinguistic individuals to communicate more flexibly, more creatively and more compatibly to the situation [73] (p. 89). These metasystems and monitoring processes are manifested through code-mixing and code-switching strategies. Code-mixing means lexical, syntactical merging of different languages. Code-switching, on the other hand, means the changing of languages while maintaining their lexical and syntactical structures [74] (pp. 63–64), [75] (pp. 1–3). The linguistic metasystem leads, among the majority of multilingual individuals, to a higher syntactical and semantic understanding, as well as an extended lexical knowledge [63], depending on what language(s) are activated and used (language mode; [76] (p. 9), [77] (pp. 610–613)). This allows multilinguals to deal with language in a more complex way, i.e., finding matching technical terms or verb or sentence constructions more easily or identifying mistakes (“language management”). Moreover, in language acquisition, they are more capable of developing mental concepts of technical terms or of conserving or expanding language skills (“language care”; “Sprachpflege”; [18] (pp. 24–25), cf. Figure 2: linguistic dimension). Content, meaning and language can possibly be constructed more coherently through more conscious monitoring and control of language production and language repertoire [39] ((p. 214); cf. Figure 2: contentual and linguistic coherence). A side effect of multilingual lesson sequences is the reduction of language monitoring processes, for a lesser need of internal and external language monitoring enables a freer use of languages. Thus, learners may invest learning-related activities into problem-solving and doing the very tasks [74] (pp. 74–75). This does not only raise the probability of learning the technical language successfully but also that of solving language-based, complex, problem-oriented tasks [78].

- (b)

- Because of their process-oriented, changing use of different language systems and structures and the connected use of different multiple meaning systems, as well as their subjective attitudes, multilingual individuals possess a transformative capacity (Figure 2: cognitive dimension) that not only affects the present language systems but also cognition processes [20] (p. 27) (cf. Figure 2: cognitive monitoring). Lewis et. al. [71] maintain that through this transformative capacity, cognitive processing skills, particularly when listening and reading, are promoted. Additionally, the multilingual language concept enhances the assimilation and accommodation of information in the mental lexicon [79] (p. 217). Language and content would then not only stimulate a linguistic translation but also a search for parallel linguistic expressions in the second (L2) and third language (L3). This switching between and within language(s) augments the transfer of meaning and the understanding of lexical and syntactic structures. This “language networking” increases the depth of cognitive processing and thereby the cross-linking in the mental lexicon, having a distinctively positive effect on learning [80] (p. 173) (cf. Figure 2: information processing in the mental lexicon). What follows further is an improved capacity to (re-) organize knowledge bases (i.a. [81], Figure 2). Language awareness facilitates the selection of information from memory, which is required for communication in oral and written form [82] (pp. 65–66). Furthermore, it is often mentioned that multilingual learners show increased creativity when dealing with problem-solving processes [63] (p. 212) (cf. Figure 2: e.g., creativity in problem-solving processes). Jessner [18] suggests that multilingual individuals, compared with monolingual ones, demonstrate stronger analytical skills. Bialystok [19] finally found that increased language awareness leads to a more intense and more complex activation of mental representations of what had already been learned, yet coded in a different language, be it previous experiences or declarative knowledge (cf. also [83]). The intensified activation of present knowledge increases the probability of understanding tasks (cf. Figure 2: task understanding) and solving complex problems, to verbalize them and incorporate/transfer them into everyday contexts [19] (p. 204), [84] (pp. 20–24).

- (c)

- Language is also an expression of identity. Multilingual lesson sequences foster a positive appreciation of the learners’ background and language. Multilinguality in the classroom thus promotes identity formation and personal development [85] (p. 25, p. 36), resulting in positive self-esteem (cf. Figure 2). Additionally, origin-related experiences, views and influence factors become an object of learning processes [3] (pp. 54–55) (Figure 2). This as a whole strengthens emotions related to learning, affecting the volitional and metacognitive control of learning behavior. Thereon depend i.a. learning motivation, the application of cognitive resources, as well as strategies of information intake and memorization [86] (pp. 153–180) (cf. Figure 2 motivation). Taking linguistic plurality into account in itself positively affects functional and intercultural learning [87] (p. 125). What is more, linguistically and culturally typical conceptualizations and ways of thinking are available for elaborating functional content and thus for functional learning [83] (cf. Figure 2: ways of thinking and causality concepts).

- (d)

- A raised language awareness finally affects social competences in a favorable way. Bredthauer [32] highlights the social dimension of multilingual lesson sequences. They increase motivation to learn languages and to participate in classroom activities. This again strengthens social and thus communicative activities of learners (cf. Figure 2: activity in the classroom; communication/interaction). Furthermore, language awareness leads to increased communicative sensitivity and metapragmatic skills [88] (p. 17). Auer [89] explains elevated discourse and interaction capabilities by language-integrating code-mixing and code-switching strategies.

Both have been described as bringing about an improved speech act capability [3] (p. 18). Therefore, multilingual individuals possess a higher “pragmatic sensitivity” [62] (p. 106) (cf. also Figure 2) and may better adapt to the language needs of their counterparts. Considering student-related multilinguality for lesson planning would finally be just another dimension of a student-oriented, internally differentiated, individual, inclusive and resource-centered learning setting [32] (pp. 280–281).

Furthermore, no studies exist so far on the actual effects of multilinguality in the context of the subject geography. It is primarily for this reason that the present study analyzes the use of multilingual learning settings and the important accompanying aspects that need to be considered.

5. Research Design

To investigate the research questions, a qualitative intervention study was conducted, with an explorative survey approach and inductive category formation [90] (pp. 222–223). The central analytical approach is qualitative content analysis according to Mayring [91,92]. The study was conducted in a quasi-experimental design; the date of the survey was in May 2019 [93] (p. 115).

5.1. Target Group, Developmental Situation and Socio-Cultural Background

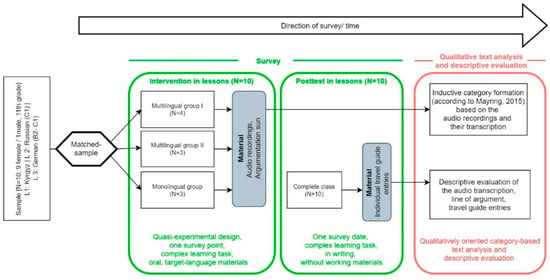

The sample group (n = 10) consisted of multilingual students in the 11th grade (9 female/1 male) at a governmental school in Bishkek/Kyrgyzstan (cf. Figure 3). One author of the present study worked as a teacher for the 16- to 17-year olds within the German foreign school service (Zentralstelle für das Auslandsschulwesen, ZfA) for the subjects German as a foreign language and German regional studies. The goal was to prepare students for the German language diploma, level II (C1).

Figure 3.

Survey design.

Besides the promotion of all basic language skills (reading, speaking, listening, writing), teaching thinking tools and strategies for successfully passing the written communication exam (discussion; “problem-focused argument”) was central. Potential exam topics were explicitly geographical issues, namely “migration” and “environment”. The study was conducted during four lessons. The group of students was picked because of their trilinguality. This yields a transfer potential to German schools abroad as well as German domestic schools, where, by now, there are also many multilingual children. The students’ mother tongue is Kyrgyz. Additionally, Russian is spoken at a native speaker level. Language skills in German are predominantly on the level B2-C1 [60]. The individual language proficiency in the third language (German) was measured based on the German language diploma, level II (Deutsches Sprachdiplom/DSD II). Students mostly belong to a better educated, urban, Kyrgyz social milieu. Learning German is generally highly favored in Kyrgyzstan, and the Sotylganow-Gymnasium in Bishkek enjoys a particularly good reputation in this respect.

5.2. Background of Material Development

Materials, tasks and tests of the present study were piloted in a 10th grade sample, tested and slightly modified [94]. Departing from a complex, problem-oriented question (“Why ought Ms. Angelika H. visit Kyrgyzstan?”), students were asked to elaborate cause–effect relations on the topic “The touristic potential of Kyrgyzstan”. The given information was based on three different topical pieces of material consisting of continuous texts in the German language (a. natural environment’s potential, b. touristic infrastructure, c. cultural space’s potential). To avoid contentual overload [95], each of the materials contained no more than 6 core pieces of information on each topical aspect. By means of this information, 10–15 factually plausible causal connections could be established. To minimize further language barriers and contentual overload, students were given scaffolding offers on 4 levels: at the sentence level, technical terms and unknown words were explained. At the sentence level, an explanation on the use of conjunctions in causal sentence structures (e.g., “if-then-connections”) was provided. A graphic presentation of causality was used to visualize the connection between word and sentence level. An argumentation sun (“Argumentationssonne”, [96]) was offered to aid with syntactical structuring of causal speech acts. Speech acts of multilingual and monolingual groups were compared in order to examine the influence of multilingual strategies and resources and their effects. The composition of the three groups took place according to a “matched sample” [90,93]. In order to increase the internal validity of the study [90] (p. 184, p. 203), two multilingual groups, that were allowed to use all potentially available languages, were established (cf. Table 1). On the one hand, relatively homogenous groups were to be formed, regarding capabilities and language skills. On the other hand, the effect of capability and language skills was to be reduced, being confounding variables that may distort results [97] (p. 5). Matching pairs were formed with regard to their German language skills (DSD II results), as well as their marks in mathematics, biology, Kyrgyz literature and Russian. In order to research metalinguistic and problem-solving strategies for establishing causal links, group discussions were recorded with mobile phones. Additionally, written results of the introduction, of the audio recordings, an observation protocol of the experimental situation and individually written guidebook entries (post-test) by students were included (Figure 3) for a methodological triangulation [98] (p. 267), [99] (p. 110). The guidebook entries were created in a lesson later on, with the target of checking the contentual quality of causal links. Thereof, the authors were hoping to conclude on the general learning effectiveness of the lessons. Moreover, individual data (guidebook accounts) were used to monitor the students’ metalinguistic competences (cf. Table 2). Causal links that were established in the scope of cooperative learning and formed contentual and linguistic duplicates were erased or accounted for only with single value (cf. Table 2).

Table 1.

Oral language actions of the multilingual groups in the group work phase.

Table 2.

Written language actions in the group work phase (argumentation sun).

5.3. Category Formation and Analysis Methods

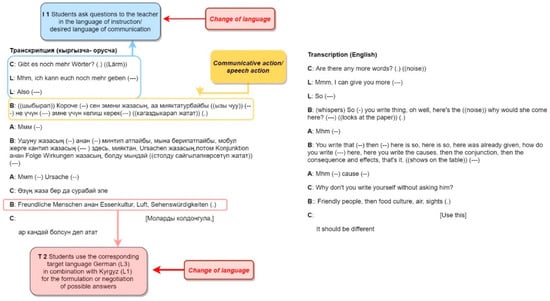

The material was analyzed by means of the approach of qualitatively oriented category-based text analysis (“qualitativ orientierte kategorienbasierte Textanalyse”, e.g., [91,92]). The basis of the analysis was the transcribed discussion records (Figure 4) of the cooperative task-solving situation.

Figure 4.

Transcription of the audio recordings of a multilingual group and examples for the assignment of the categories.

Based on the transcripts (evaluation unit; [91] (p. 88)), inductive analytical categories were formed (Figure 4). Individual categories designate specific resources and strategies of multilingual students (e.g., T 2, Figure 4), which were applied when dealing with a geographical problem issue and used for developing causal links (category definition; “Kategoriendefinition”; [91] (p. 88). For category formation (selection criteria; “Selektionskriterium”), various forms of translanguaging, like language variations, language-switching or language innovation (e.g., “code-mixing), were examined at word and sentence level ([91] (p. 70); Figure 4). As a coding unit (“Kodiereinheit”; [91] (p. 88), a meaningful speech act (“Sprachhandlung”; [100] (p. 140), Figure 4.) was determined. A speech act was, according to the speech act theory by Searle [101], understood as the communicative unity of locutionary act, propositional act, illocutionary act and perlocutionary act (cf. Figure 4). Individual speech acts in the transcript were then identified and categorized, based on identifiable contentual or linguistic (communicative) relations which were required by the students’ situative, task-related, multilingual solution strategy (Figure 4, categories I 1 and T 2).

In two subsequent reduction phases, the categories were overworked and intra-coder tests conducted. After the final material stage, an inter-coder test was conducted for interpersonal reliability testing [92] (p. 550). Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the transcripts followed.

For a quantitative, descriptive analysis of the results, the causal links of the argumentation sun (Figure 5, transcript of two causal links) and the guidebook entries (Figure 6) were checked as to the correct contentual and linguistic construction of the effect relationship. They were analyzed and evaluated regarding the linguistically and contentually coherent use of technical terms (e.g., “nature”), indicative verbs/adverbs (e.g., “leads to”), conjunctions (e.g., “because”) and a main clause–subordinate clause construction (analysis of causal links, cf. [31]).

Figure 5.

Causal links from the argumentation sun of a multilingual group as examples.

Figure 6.

Travel guide entry about the tourism potential of a schoolgirl—post-test.

Beyond this, the individually written guidebook entries were evaluated regarding the used spatial information and causal speech acts. The variety of materials used was expected to generate high internal and external validity, reliability and objectivity of the qualitative content analysis, and is moreover to make sure that artefacts do not lead to false conclusions [90] (p. 184).

5.4. Results

In the following, the linguistic actions with regard to the individual products are explained descriptively. Subsequently, the results of the content analysis are presented.

5.4.1. Descriptive Depiction of Communicative Actions

The multilingual group produced 186 speech acts with a total of 843 words (Table 1) during the oral, cooperative work phase (Table 1). The monolingual group, which was only permitted to communicate in German, as it is the case in common language lessons, however, had only 98 speech acts consisting of a total of 515 words (Table 1.). There is a first hint that, concerning interaction and communication, multilingual learning settings are more fruitful than monolingual ones. One remarkable feature is the great number of pauses among the multilingual group. This may be a sign that they require higher cognitive processing efforts, compared with the monolingual group (Table 2). The language used by the multilingual group during the cooperative tasks was mainly Kyrgyz, followed by German (25%) and Russian (9%, Table 1).

What sticks out about how the groups managed the content is that the multilingual ones showed a greater number of contentual aspects (Table 2), causal links (Table 2) and a higher range of expressions in their written speech acts (Table 2). Apparently, the multilingual method has a positive effect on the creation and communication of formal links. The monolingual group produced various repetitions, providing the same contentual aspects that were hence not noted as separate speech acts.

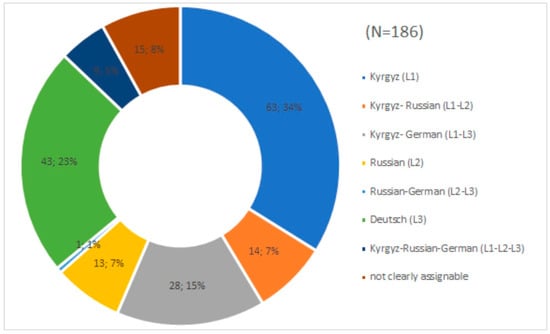

The share of languages used by the multilingual group I in the course of the oral work stage (cf. Figure 7) is dominated by Kyrgyz with 34%, followed by German with 23%. The most prominent language-switching within a single communicative act happened between Kyrgyz and German (15%). This can likely be explained by the given task, since the product of the communicative action (individual guidebook entries) had to be written in German at the end of the lesson. What is interesting is the scarce use of all three languages within the scope of a single communicative action (at just 5%), the little exclusive use of the Russian language (7%) and the rare switching between Russian and German (1%, cf. Figure 7). All three aspects provide evidence on the immanent correlation between the uses of available language systems, affected by the monolingual materials and the speech act product in the target language.

Figure 7.

Share of languages in the communicative activities of multilingual groups during the teaching intervention.

What stuck out in the post tests was the low number of causal links (n = 14) in a total of 109 written speech acts concerning the individual guidebook entries (cf. Table 3). Although the use of several languages had positively affected the establishment of causal links, students were only partly able to reproduce these in their written work. This gives a clue that written communication in the foreign language poses a particularly great challenge, probably needing targeted didactic support. Multilingual groups did not continuously produce a higher range of vocabulary in the post-test (Table 3); they used, however, on average, more contentual aspects (Table 3), being a clue for the greater factual quality of the texts produced. It should be highlighted that the causal links produced by the three groups show a significant degree of contentual and linguistic coherence and thus a higher degree of correctness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Individual written language actions in the post-test.

5.4.2. Qualitative Results of the Content Analysis on the Post-Tests

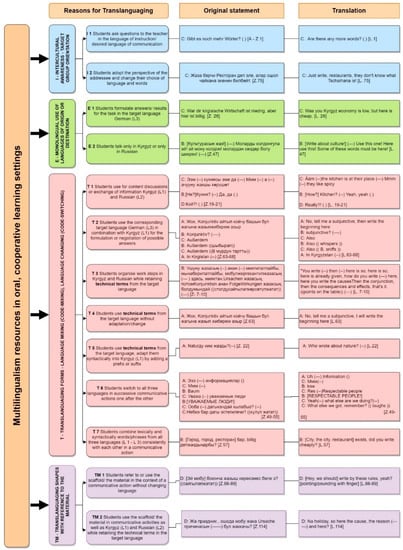

The inductive category formation [91] (ch. 5.3.), based on the transcript of the multilingual group, yielded four central categories. Each of them characterizes different forms of translanguaging or the use of resources of multilinguality (cf. Figure 8). Intercultural awareness (I, Figure 8, blue) depicts the language choice of multilingual students according to their counterparts’ language abilities (cf. also Figure 4). Monolingual use of heritage language and target language (E, Figure 8, green) depicts communicative actions that took place either only in the mother tongue Kyrgyz or the target language, German. Speech acts that occurred in Russian only were not recorded as a separate category and summed up in E 2 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Resources and strategies of multilingual pupils in cooperative, oral learning settings within the exploratory study (inductive category building according to Mayring, 2015, own presentation).

Forms of translanguaging in the field of multiorality (T 1-7, Figure 8, pink) are marked by language-mixing (T 1, T 2, T 6; Figure 8) at the sentence level without altering individual words and with no language shifting between finished secluded communicative actions. Additionally, there are communicative actions where code-switching at the sentence level and code-mixing strategies at the word level, normally by altering geographical or grammatical technical terms, appear simultaneously (T 3, T4, T 7, Figure 8). Reference to the material in connection with forms of translanguaging was given the category TM (Figure 8, violet). For discussing complex issues, work organization and in the case of contentual or linguistic communication difficulties (Figure 8, T1), the multilingual group used Kyrgyz (L 1) and Russian (L 2). Thereby, technical terms at the word level were often taken from the target language, German (L 3), and incorporated syntactically or semantically (code-switching). This happened, however, supposedly only in those cases where the contentual/semantic representation of the word in language L3 was known to everyone in the classroom. The use of those specific terms in L 3 helped then as a lexical means to reduce langue challenges (Figure 8, T 4-T 6). Technical terms were furthermore assimilated through code-mixing strategies, like, e.g., adding a prefix or suffix.

Contentual language production for achieving particular results took place in the target language, German, when technical terms and important phrases in the target language, German (L 3), played a major role. Here, Kyrgyz (L 1) or Russian (L 2) had a coordinating, organizing function and were used when words were missing in German (L 3). In these situations, semantically matching “spare words“ from L 1 and L 2 were used, which closed the lexical gaps in the target language (Figure 8, T 2). The students communicated in their target language, as soon as lingual and contentual problems as well as unclarities had been cleared up. Another prerequisite was a sufficient (technical) language register to execute the discursive speech acts (Figure 8, E 1). Basically, language-switching happened for functional reasons, i.e., effectivity and efficiency of the communicative act with regard to the communication objective. Depending on availability and functional fitting, an optimal balance between the communicative intention and available language means (mental lexicon) of the active language system was strived for. Changing the language was either prompted by a trigger word (e.g., technical terms) or by an external stimulus (e.g., the task, multilingual material, students’ work, teacher’s stimulus; tab 8, E 2). Supposedly, also, changing the language increased the matching of the communicative intention and available linguistic means. If none of the situations mentioned above occurs, normally, no language change takes place. Contentual reference to the given material (e.g., texts or scaffold) which was written in L 3 presumably triggered two strategies. Where the words in L 3 were known and the language structure of the material was useful for solving the task, both contentually and linguistically, no language change took place (Figure 8, TM 1). If, however, reference to the material (in L 3) happened with regard to the desired communication product and students faced linguistic or contentual difficulties, the language was changed. Additionally, the linguistic systems of L 1 and L 2 were applied as a support for decoding and constructing the target language (Figure 8, TM 2).

6. Discussion

In the course of the study, students showed very positive reactions to the given opportunity to use their multilingual resources for task-solving. High motivation and readiness to work were the consequence and confirmed the findings of Repplinger & Budke [16]. Based on the results (ch. 5.4), it can be concluded that the free choice of language by itself promotes a functional activation of multilinguals’ resources (ch. 4.2.). This leads to a more complex contentual understanding of geographical topics (Table 3). Multilingual lesson sequences promote declarative and procedural cognition processes that affect learning and stimulate functional learning (i.a. [20,102]). This underlines the importance and potential of multilingual learning settings in the German domestic and foreign school system. Multilingual learning settings open an additional opportunity for interdisciplinary and subject-related language and learning promotion. The outcomes of this study suggest that the lingual heterogeneity of students, often perceived as a shortcoming or source of disturbance, might rather be a major potential. This is particularly effective when teaching central cognitive competences, like problem-solving or thinking in systems [43] (pp. 8–11), within the frame of the geography classroom (e.g., causal links referring to climate change). High motivation and the absence of language barriers through the free choice of language and without compulsory communication in the target language raise the scope of communicative actions. This elevates interactions in the classroom as well as learning-related activation level and thus the intensity of the communicative problem-solving process (Table 3, i.a. [103]). Multilingual individuals are able to reduce linguistic complexity in a problem-solving process in a more targeted way by using different languages (code-switching) and connecting language varieties (code-mixing) and by activating their extended mental lexicon in cooperative learning methods. They are also better at constructing contentual aspects and their significance (Table 3). This can be compared with the results of Roche [82] and Bär [102], who stated better learning outcomes due to the transfer effects resulting from an increased language awareness of multilingual learners. Communicative actions are made in relation to the language skills of the addressee, probably brought about by a pragmatic sensitivity [62] (p. 106); ch. 4.2.)—insofar as students are aware of the preferred language of their counterpart and understanding is facilitated as a consequence (Figure 8, I 1-2).

Fundamentally, the supposition is at hand that using all languages (L 1-L3, Figure 7) helps in that understanding processes and contentual negotiation processes could be done in a more targeted and efficient way [74] (pp.74–75). This begins with task clarification and securing task understanding and stretches over coordination and controlling of the work process up to the strategies for contentual understanding, e.g., meaningful reading (“sinnentnehmendes Lesen”; transformative capacity/”transformative Kapazität”, [20] (p. 15); ch. 4.2.). The linguistic and cognitive metasystem [42] (pp. 35–37) and the enhanced language awareness of multilinguals [104] presumably lead to greater linguistic and contentual coherence and thereby a more distinct correctness and a higher number of causal links (Table 3). With regard to the results of the monolingual group in particular, it can be concluded that using multilingual resources in the geography classroom has a positive effect on content-related communicative actions (Table 3, Figure 8 T 1-7 and TM 1-2) and thus supports functional learning (cf. also [80]). Whether advantages are generated for learning the technical language could not be concluded from this study. In the course of this survey, it has, however, become obvious that multilinguality likely has no influence on the construction of multi-causal links—a finding that corresponds with previous studies, where mono-causal links had also been found to be predominant [31,105]. Likewise, the enriching effect of an intercultural grasp on causal links did not come into identifiable effect in the present study. The individual language systems are used according to their functional meaningfulness or caused by a stimulus (trigger-words; [74,82]). Since the given material was only monolingual (German, L 3), the Russian language system was activated merely in a limited scope [76]. Possibly, linguistic and contentual resources were therefore not adequately exploited. Kyrgyz (L 1) was used as a linguistic referential system (“language mode”, ch. 4.2, Figure 7). Code-switching for technical terms and product-oriented communicative actions was founded on functionally mobilized speech act skills [106] (p. 56). It depended, nevertheless, on the scope of the inter-individual technical register. An explanation for the rarity of contentual discussions might be that the audio recording, in connection with the Kyrgyz error culture, had a significant impact on students’ behavior (reactivity, [98] (p. 371). Long pauses in conversations, the great amount of filling words and conversational particles, obvious unease (side activities, laughter), as well as the little language flow and faltering communication give evidence for avoidance strategies on the one hand and thinking breaks for language shifting on the other (avoidance of efforts, [107] (pp. 8–14)). A clear distinction between the two can hardly be accomplished.

7. Conclusions

This study makes it clear that overcoming the “monolingual habit” (“monolingualer Habitus“; [108] (pp. 30–34)) at schools, in connection with a resource-oriented approach in dealing with multilinguality, has a variety of positive effects on the communicative actions of multilingual students. This has been worked out particularly for geography classes. Free choice of the language supports the use of multilingual resources and strategies (cf. Table 4: permitting multilinguality). Thereby, functional learning—here, specifically, the establishment of causal links—is encouraged and promoted. What is particularly significant is the positive effect of multilingual orality on the increased contentual and linguistic coherence of causal links in geography classes. This is reflected in the multilingual students’ correct lingual representations of functional (geographical) causalities, e.g., by the appropriate choice of syntactical (e.g., sentence types) and lexical (e.g., conjunctions/subjunctions) means. Multilingual content might, especially in the German school sector abroad, allow an effective acquisition of knowledge in regional studies and geography through negotiation processes, speech synthesis and language-mixing. In the German domestic school system, multilunguality might likewise bring about positive effects concerning communicative and inclusive aspects. Pupils with a migrant background and non-German languages of origin in particular may interact and participate in the lesson more actively [84]. Raised participation may increase attention, enhance the chances of their learning success and thus the acquisition of subject-related contentual and linguistic competences. This means, specifically for geography lessons, making the cultural and linguistic heterogeneity an object of learning on the one side and a starting point for learning on the other (cf. Table 4). Using the present congnitive and linguistic resources in a functionally and didactically elaborate manner may thus be applied in a profitable way for obtaining technical competences [43] (pp. 5–8).

Table 4.

Multilingualism in geography lessons for the promotion of causal language acts (modified and supplemented after Prediger, Uribe & Kuzu, 2019).

A central precondition is a positive attitude of the teacher towards multilingual teaching approaches [109] (pp. 5–6). Duarte [110] (p. 13) recommends teachers to create secure spaces where they experiment with several languages and may functionally operationalize multilingual learning for their own context and their own targets. With reference to Prediger, Uribe & Kuzu [84] (p. 24), different options on how to deal with multilinguality in geography classes have been developed and presented (cf. Table 4). Handling multilinguality in geography classes functionally, i.e., from “allowing multilinguality” to “reflecting on multilinguality” (cf. Table 4), can enable the productive application and promotion of multilingual-communicative competences (MMK) [3] (pp. 321–323). Additionally, it would pose an enriching element to lessons in a multilingual school practice. On the input part, teachers ought to initiate tasks, materials and communication stimuli in such a way as to allow multilingual communication situations or products (cf. Table 4: actions and examples). Aimed didactic application of multilinguality can promote the multilingual competences of students and help to achieve targets in the subject itself (e.g., fostering the understanding of human geographical systems, [43] (p. 14)). This can be accomplished through, e.g., functional valorization of origin-related spatial interpretative schemes, of intercultural knowledge, of diverging construction of meaning within geographical concepts, of available linguistic comparison structures, etc. (Table 4: encouraging multilinguality). According to our findings, multilinguality can improve the quality of students’ addressing of lesson content as well as their interaction in the classroom (cognitive and volitional function). The application of several languages can, beyond this, be used for differentiation and individual support (scaffolding function, [111] (p. 134)). Potential objections, like that of a lack of control over classroom processes by the teacher or the insufficient target-orientation in students’ work, can be rejected as unjustified, based on present empirical evidence [110] (pp. 12–13). Learning in the target language and technical language can be secured by respective reformulation in German at the end of central lesson sequences, flanked by metalingual phases (epistemic function, Table 4, reflecting multilinguality) [80] (pp. 172–173). There, metacognitive phases seem crucial, enabling the establishment of language awareness related to both technical and target languages. This promotes not only the extension of the technical register but is at the same time a prerequisite for a consolidation of geographical knowledge and thinking. This is because improved linguistic skills allow, after all, more complex contentual and methodical strategies of understanding and thus more profound (geographical) insights [112] (pp. 64–65). This study also reveals that, apart from empirical testing and conceptualization of the possible uses named above, (multilingual) support measures must be developed and scholarly elaborated, aiming at teaching multi-causal, systemic strategies of thinking and their linguistic representation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and A.B.; Data curation, J.H.; Investigation, J.H.; Methodology, J.H. and A.B.; Supervision, A.B.; Validation, J.H. and A.B.; Visualization, J.H.; Writing—original draft, J.H.; Writing—review & editing, J.H. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung (Hg.) (Ed.) Bildung in Deutschland 2018: Ein Indikatorengestützter Bericht Mit Einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration; wbv: Bielefeld, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomen-Welke, I.; Dirim, I. Mehrsprachigkeit in der Klasse: Wahrnehmen-aufgreifen-fördern. In Mehrsprachigkeit in der Klasse wahrnehmen—Aufgreifen—Fördern, 1. Aufl.; Oomen-Welke, I., Ed.; Fillibach bei Klett: Stuutgart, Germany, 2013; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, G. Kompetenzentwicklung und Mehrsprachigkeit: Eine Unterrichtsempirische Studie zur Modellierung Mehrsprachiger Kommunikativer Kompetenz in der Sekundarstufe II, 1st ed.; Gießener Beiträge zur Fremdsprachendidaktik; Narr Francke Attempto: Tübingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolin, I.; Hansen, A.; Leseman, P.; McMonagle, S.; Rauch, D. (Eds.) Handbuch Mehrsprachigkeit und Bildung, 1st ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Titz, C.; Hasselhorn, M. Sprachförderliche Maßnahmen im Elementarbereich. Ein erfolgsversprechender Weg zur Prävention von Bildungsmisserfolg. In Sprachliche Bildung—Grundlagen und Handlungsfelder; Becker-Mrotzek, M., Roth, H.-J., Eds.; Waxmann: Munster, Germany, 2017; pp. 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner, U.; Prediger, S. Alltagsintegrierte Sprachbildung im Fachunterricht—Fordern und Unterstützen fachbezogener Sprachhandlungen. In Konzepte zur Sprach- und Schriftsprachförderung entwickeln; Titz, C., Geyer, S., Ropeter, A., Wagner, H., Weber, S., Hasselhorn, M., Eds.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; pp. 228–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zentralstelle für das Auslandsschulwesen. ZfA-Kurz Gefasst. Available online: https://www.auslandsschulwesen.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/Webs/ZfA/DE/Publikationen/ZfAkurzgefasst.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Budke, A.; Kuckuck, M.; Meyer, M.; Schäbitz, F.; Schlüter, K.; Weiss, G. (Eds.) Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern, 1st ed.; Waxmann Verlag GmbH: Munster, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, V.; Ganteford, C. Sprachliche Bildung im Fachunterricht. In Migration und Geographische Bildung; Geographie; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Eds.; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Language awareness in Geography education: An analysis of the potential of bilingual Geography education for teaching Geography to Language learners. Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 8, 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Böing, M.; Grannemann, K.; Lange-Weber, S. Cluster Gesellschaftswissenschaften. In Sprachsensibles Unterrichten Fördern: Angebote für den Vorbereitungsdienst, 1st ed.; Oleschko, S., Grannemann, K., Eds.; W. Kohlhammer Gambh: Arnsberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 70–100. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A.; Schäbitz, F.; Reich, J. Sprachsensibles Material für die Kartenauswertung in Vorbereitungsklassen und im sprachbewussten Geographierunterricht. In Sprache im Geographieunterricht: Bilinguale und Sprachsensible Materialien und Methoden; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Munster, Germay, 2017; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Oleschko, S.; Weinkauf, B.; Wiemers, S. Praxishandbuch Sprachbildung Geographie: Sprachsensibel unterrichten-Sprache fördern, 1st ed.; Ernst Klett Sprachen GmbH: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze, S. Sprachsensibler Geographieunterricht. In Sprachliche Vielfalt im Unterricht; Danilovich, Y., Putjata, G., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Maier, V. Multilingualität in Schule und Hochschule—Erfahrungen und Vorstellungen von Studierenden im Lehramt Geographie. GW Unterr. 2019, 1, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repplinger, N.; Budke, A. Is multilingual life practice of pupils a potential focus for Geography lessons? Eur. J. Geogr. 2018, 9, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann, M. An Introduction. In The Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner, U. Language Awareness in Multilinguals: Theoretical Trends. In Language Awareness and Multilingualism; Cenoz, J., Gorter, D., May, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. Bilingualism in Development: Language, Literacy, and Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 39, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehren, R.; Rempfler, A.; Buchholz, J.; Hartig, J.; Ulrich-Riedhammer, E.M. System competence modelling: Theoretical foundation and empirical validation of a model involving natural, social and human-environment systems. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2018, 55, 685–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehren, R.; Rempfler, A.; Ulrich-Riedhammer, E.; Bucholz, J.; Hartig, J. Wie lässt sich Systemdenken messen? Darstellung eines empirisch validierten Kompetenzmodells zur Erfassung geographischer Systemkompetenz. Geogr. Aktuell Sch. 2015, 37, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, A.; Beller, S. Current Perspectives on Cognitive Diversity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisen, J. Handbuch Sprachförderung im Fach: Sprachsensibler Fachunterricht in der Praxis; Grundlagenwissen, Anregungen und Beispiele für die Unterstützung von sprachschwachen Lernern und Lernern mit Zuwanderungsgeschichte beim Sprechen, Lesen, Schreiben und Üben im Fach; Ernst Klett Sprachen GmbH: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ehret, C. Mathematisches Schreiben; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Deutsch lernt man im Deutschunterricht. In Sprache als Lernmedium im Fachunterricht: Theorien und Modelle für das sprachbewusste Lehren und Lernen; Michalak, M., Lemke, V., Goeke, M., Eds.; Narr Francke Attempto: Tübingen, Germany, 2015; pp. 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Weiss, G. Sprachsensibler Geographieunterricht. In Sprache als Lernmedium im Fachunterricht: Theorien und Modelle für das sprachbewusste Lehren und Lernen, 2nd ed.; Michalak, M., Ed.; Schneider Verlag GmbH: Hohengehren, Germany, 2017; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Kuckuck, M. Sprache im Geographieunterricht. In Sprache im Geographieunterricht: Bilinguale und sprachsensible Materialien und Methoden; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Munster, Germay, 2017; pp. 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum age question and some other matters. Work. Pap. Biling. 1979, 19, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, P. Scaffolding Language Scaffolding Learning: Teaching English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom, 2nd ed.; Heinemann: Portsmouth, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heuzeroth, J.; Budke, A. Formulierung von fachlichen Beziehungen- Eine Interventionsstudie zur Wirkung von sprachlichen Scaffolds auf kausale Sprachhandlungen im Geographieunterrichtunterricht. J. Geogr. Educ. (to be submitted for publication).

- Bredthauer, S. Mehrsprachigkeitsdidaktik an deutschen Schulen—Eine Zwischenbilanz. DDS 2018, 110, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, B. Mehrsprachigkeit, 2nd ed.; Facultas: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weißenburg, A. “Der mehrsprachige Raum“—Konzept zur Förderung eines mehrsprachig sensiblen Geographierunterrichts. GW Unterr. 2013, 131, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Weißenburg, A. Mehrsprachiger Fachsprachenaufbau im Geographieunterricht. GW Unterr. 2018, 149, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hasselhorn, M.; Gold, A. Pädagogische Psychologie: Erfolgreiches Lernen und Lehren, 3., Vollständig Überarbeitete und Erweiterte Auflage; Verlag W. Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner, C.; White, J. Language Awareness and Multilingualism: A Historical Overview. In Language Awareness and Multilingualism, 3rd ed.; Cenoz, J., Gorter, D., May, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lockl, K.; Schneider, W. Entwicklung von Metakognition. In Handbuch der Entwicklungspsychologie; Hasselhorn, M., Schneider, W., Bengel, J., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2007; pp. 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm, K. Metakogntion. In Metzler Lexikon Fremdsprachendidaktik; Surkamp, C., Ed.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Haukas, A. Metacognition in Language: Learning and Teaching. In Metacognition in Language Learning and Teaching; Åsta, H., Bjørke, C., Dypedahl, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allemann-Ghionda, C.; Stanat, P.; Göbel, K.; Röhner, C. Migration, Identität, Sprache und Bildungserfolg –Einleitung zum Themenschwerpunkt. In Migration, Identität, Sprache und Bildungserfolg: 55. Beiheft, 1st ed.; Allemann-Ghionda, C., Ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner, U. Metacognition in Multilingual Learning. In Metacognition in Language Learning and Teaching; Åsta, H., Bjørke, C., Dypedahl, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie. Bildungsstandardsstanddards im Fach Geographie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss: Mit Aufgabenbeispielen, 9th ed.; Selbstverlag: Bonn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Freyer, W. Tourismus: Einführung in die Fremdenverkehrsökonomie, 11., Überarbeitete und Aktualisierte Auflage; Lehr- und Handbücher zu Tourismus, Verkehr und Freizeit; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, B. Komplexe Mensch-Umwelt-Systeme im Geographieunterricht mit Hilfe von Argumentationen erschliessen: Am Beispiel der Trinkwasserproblematik in Guadalajara (Mexikao). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cologne, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asmuth, C. Kausalität. In Metzler Lexikon Philosophie, 3.,Aktualisierte Auflage; Prechtl, P., Burkard, F.-P., Eds.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2008; p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziale Systeme: Grundriß Einer Allgemeinen Theorie, 17. Auflage; Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Volume 666. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, J. Luhmann-Lehrbuch; UTB Soziologie; Fink: Paderborn, Germany, 2004; Volume 2486. [Google Scholar]

- Dörner, D. Die Logik des Mißlingens: Strategisches Denken in komplexen Situationen, 13. Auflage; Rowohlt: Hamburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, E. From Etymology to Pragmatics-Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Breindl, E.; Walter, M. (Eds.) Der Ausdruck von Kausalität im Deutschen: Eine korpusbasierte Studie zum Zusammenspiel von Konnektoren, Kontextmerkmalen und Diskursrelationen; Amades; Inst. für Dt. Sprache: Mannheim, Germany, 2009; Volume 38. [Google Scholar]

- Blühdorn, H. Kausale Satzverknpüfungen im Deutschen. Pandaemonium Ger. 2006, 10, 253–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabunde, R. Semantik- die Bedeutung von Wörtern und Sätzen. In Linguistik: Eine Einführung (Nicht nur) für Germanisten, Romanisten und Anglisten; Dipper, S., Klabunde, R., Mihatsch, W., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rödel, M. Kausalsatz. In Metzler Lexikon Sprache, 5th ed.; aktualisierte und berarbeitete Auflage; Glück, H., Rödel, M., Eds.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Hoberg, U.; Hoberg, R. Duden: Deutsche Grammatik. Duden pur.; Dudenverlag: Mannheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, D.M.; Fishman, J.A.; Aronin, L.; Ó Laoire, M. (Eds.) Current Multilingualism: A New Linguistic Dispensation; Contributions to the Sociology of Language /CSL; de Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Volume 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronin, L.; Laoire, M.Ó. Exploring Multilingualism in Cultural Contexts: Towards a Notion of Multilinguality. In Trilingualism in Family, School and Community; Bilingual education & bilingualism; Hoffmann, C., Ytsma, J., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini, R. Multilingualism and Multicompetence: A Conceptual View. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.C. Multilingualism: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. Mehrsprachigkeit. In Metzler Lexikon Fremdsprachendidaktik; Surkamp, C., Ed.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; pp. 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdi, G.; Nelde, P.H. Instead of a foreword: Codeswitching as a litmus test for an integrated approach to multilingualism. In Codeswitching; sociolinguistica; Lüdi, G., Nelde, P.H., Eds.; Niemeyer: Tübingen, Germany, 2004; Volume 18, pp. VII–XII. [Google Scholar]

- Herdina, P.; Jessner, U. A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism: Perspectives of Change in Psycholinguistics; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK; Buffalo, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner, U.; Allgauer-Hackl, E. Mehrsprachigkeit aus einer dynamisch-komplexen Sicht oder warum sind Mehrsprachige nicht einsprachig in mehrfacher Ausführung? In MehrSprachen?—PlurCur!: Berichte aus der Forschung und Praxis zu Gesamtsprachencurricula; Allgäuer-Hackl, E., Brogan, K., Henning, U., Hufeisen, B., Schlabach, J., Eds.; Schneider: Seine, France, 2015; pp. 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Trim, J.L.M. (Ed.) Gemeinsamer europäischer Referenzrahmen für Sprachen: Lernen, lehren, beurteilen; Klett-Langenscheidt: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Bot, K. Dynamische Modellierung von Spracherwerb. In Mehrsprachigkeit und Sprachenerwerb; Kompendium DaF/DaZ Band 4; Roche, J., Terrasi-Haufe, E., Eds.; Narr Francke Attempto: Tübingen, Germany, 2018; pp. 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, N.; Kupisch, T.; Schmitz, K. (Eds.) Einführung in die Mehrsprachigkeitsforschung; Gunter Narr Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolin, I. Mehrsprachigkeit. In Stichwort: Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft; Gogolin, I., Kuper, H., Krüger, H.-H., Baumert, J., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiedbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Garibova, J. Mehrsprachigkeit. Historische und kommunikative Aspekte. In Mehrsprachigkeit und Sprachenerwerb; Kompendium DaF/DaZ Band 4; Roche, J., Terrasi-Haufe, E., Eds.; Narr Francke Attempto: Tübingen, Germany, 2018; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, V.J. Evidence for Multicompetence. Lang. Learn. 1992, 42, 557–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessner, U. The nature of cross-lingusitic interaction in the multilingual system. In The Multilingual Lexicon; Cenoz, J., Hufeisen, B., Jessner, U., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.; Jones, B.; Baker, C. Translanguaging: Origins and development from school to street and beyond. Educ. Res. Eval. 2012, 18, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S.; García, O. Translanguaging. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-181 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Jessner, U. Linguistic Awareness in Multilinguals: English as a Third Language; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehl, C. Codeswitching, mentale Vernetzung und Sprachbewusstheit. In Ein Kopf-Viele Sprachen: Koexistenz, Interaktion und Vermittlung; Müller-Lancé, J., Riehl, Claudia, Maria, Eds.; Shaker Verlag: Herzogenrath, Germany, 2002; pp. 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Riehl, C. Code-Switching. Available online: https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/61752/1/RiehlCode-Switching.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Grosjean, F. Bilingual and Monolingual Language Modes. En 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.L.; Fox Tree, J.E. More on language mode. Int. J. Biling. 2014, 18, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamot, A.U. Issues in Language Learning Strategy Research and Teaching. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2004, 1, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Neveling, C. Mentales Lexikon. In Metzler Lexikon Fremdsprachendidaktik; Surkamp, C., Ed.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Schüler-Meyer, A.; Prediger, S.; Wagner, J.; Weinert, H. Bedingungen für zweisprachige Lernangebote. Videobasierte Analysen zu Nutzung und Wirksamkeit einer Förderung zu Brüchen. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 2019, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazak, C. Introduction: Theorizing Translanguaging Practices in Higher Education. In Translanguaging in Higher Education beyond Monolingual Ideologies; Bilingual education & bilingualism; Mazak, C., Carroll, K.S., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK; Buffalo, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 104, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, J. Modellierung von Mehrsprachigkeit. In Mehrsprachigkeit und Sprachenerwerb; Kompendium DaF/DaZ Band 4; Roche, J., Terrasi-Haufe, E., Eds.; Narr Francke Attempto: Tübingen, Germany, 2018; pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Prediger, S.; Redder, A. Mehrsprachigkeit im Fachunterricht am Beispiel Mathematik. In Handbuch Mehrsprachigkeit und Bildung, 1st ed.; Gogolin, I., Hansen, A., Leseman, P., McMonagle, S., Rauch, D., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prediger, S.; Uribe, Á.; Kuzu, T. Mehrsprachigkeit als Ressource im Fachunterricht: Ansätze und Hintergründe aus dem Mathematikunterricht. Learn. Sch. 2019, 86, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fürstenau, S. Mehrsprachigkeit als Vorraussetzung und Ziel schulischer Bildung. In Migration und schulischer Wandel: Mehrsprachigkeit, 1st ed.; Fürstenau, S., Gomolla, M., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Schiefele, U. Emotions- und motivationspsychologische Bedingungen der Lernleistung. In Psychologie des Lernens und der Instruktion; Enzyklopädie der Psychologie Praxisgebiete Pädagogische Psychologie Bd. 2; Weinert, F.E., Birbaumer, N.-P., Graumann, C.F., Eds.; Hogrefe Verl. für Psychologie: Göttingen, Germany, 1996; pp. 153–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bredella, L. Interkulturelles Lernen. In Metzler Lexikon Fremdsprachendidaktik; Surkamp, C., Ed.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gnutzmann, C. Bewusstheit/Bewusstmachung. In Metzler Lexikon Fremdsprachendidaktik; Surkamp, C., Ed.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, P. Competence in performance: Code-switching und andere Formen bilingualen Sprechens. In Streitfall Zweisprachigkeit—The bilingualism controversy, 1st ed.; Gogolin, I., Neumann, U., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 12., Überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, 2. Auflage; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.R.; Cook, T.D.; Campbell, D.T. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs: Designs for Generalized Causal Inference; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weichhold, M. Pretest. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, 2nd ed.; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Paas, F.; Renkl, A.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory: Instructional Implications of the Interaction between Information Structures and Cognitive Architecture. Instr. Sci. 2004, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckuck, M. Argumente arrangieren mit der Argumentationssonne. In Diercke-Kommunikation und Argumentation; Budke, A., Ed.; Westermann: Braunschweig, Germany, 2012; pp. 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Schwieter, J.W. Recognizing the Effects of Language Mode on the Cognitive Advantages of Bilingualism. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamnek, S.; Krell, C. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Mit Online-Materialien, 6., Überarbeitete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pryzborski, A.; Wohlrab-Sahr, M. Forschungsdesigns für die qualitative Sozialforschung. In Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung, 2. Auflage; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Röska-Hardy, L. Sprechen, Sprache, Handeln. In Intention—Bedeutung—Kommunikation: Kognitive und handlungstheoretische Grundlagen der Sprachtheorie, [Elektronische Ressource]; Preyer, G., Ulkan, M., Ulfig, A., Eds.; Humanities Online: Frankfurt, Germany, 2001; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J.R. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language, 34. Auflage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, M. Förderung von Mehrsprachigkeit und Lernkompetenz: Fallstudien zu Interkomprehensionsunterricht mit Schülern der Klassen 8 bis 10. Ph.D. Thesis, Giessen University, Giessen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Prediger, S.; Kuzu, T.; Schüler-Meyer, A.; Wagner, J. One mind, two languages—Separate conceptualisations? A case study of students’ bilingual modes for dealing with language-related conceptualisations of fractions. Res. Math. Educ. 2019, 21, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]