Abstract

The rapid popularization of digital technology is profoundly altering the employment landscape; especially in rural areas, the digital economy has opened up unprecedented channels to narrow the gender gap in non-agricultural employment. This study utilizes data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2014 to 2020, employing a two-way fixed effects model to systematically examine the impact of digital literacy on the non-agricultural employment transition of rural women. The findings demonstrate that integrating social learning theory with digital empowerment theory establishes a dual-pathway analytical framework for examining psychological capital and information environments. Through skill development and resource optimization, digital literacy significantly enhances rural women’s employment participation and occupational re-adaptability, with these effects varying across regions and generations. Furthermore, the study reveals how household economic resources and regional development levels exert differential influences on these outcomes by affecting the acquisition and application of digital skills. These findings expand theoretical understanding of non-agricultural employment mechanisms in the digital era and offer practical policy insights. They also provide evidence-based strategies for enhancing women’s employment quality, advancing gender equality, and promoting rural revitalization, offering valuable guidance for developing countries navigating employment challenges through digital transformation.

1. Introduction

The global digital transformation is fundamentally reshaping economic systems and employment structures, serving as a critical driver for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. World Bank data from 2023 indicates that between 2000 and 2022, the information technology services sector expanded at twice the rate of overall economic growth, with employment in digital services growing by 7% annually compared to just 1% for overall employment, clearly demonstrating digital technology’s transformative impact on labor markets (Autor, 2015). Digital literacy has evolved significantly from its original conceptualization as basic information processing capability (Gilster, 1997) to become a multidimensional skillset encompassing technical operation, content creation, and social participation (Martin & Grudziecki, 2006). This evolution reflects its current status as essential social capital in the digital era (Eshet, 2012). The dual characteristics of digital literacy, combining technological integration with social adaptation, provide a theoretical basis for understanding its empowering potential for vulnerable populations.

The unequal distribution of digital empowerment manifests most prominently along urban–rural and gender dimensions. Recent data from the European Union Statistics Office (2023) reveals a significant disparity: while internet penetration reaches 91%, merely 55.6% of the population possesses basic digital skills, with cross-country variations in ICT training further exacerbating the digital divide (Hargittai, 2002). China’s National Report on Digital Literacy and Skills Development (2024) highlights this inequality, showing that 19.83% of urban workers demonstrate advanced digital literacy compared to only 9.53% in rural areas. Rural women face particularly acute disadvantages, experiencing compounded digital exclusion at the intersection of geographic and gender barriers (Dijk, 2005). This exclusion has tangible economic consequences. Despite China’s rural e-commerce sector growing at 8.62% annually from 2020 to 2024, rural women’s limited digital access has prevented equitable participation in these technological benefits (Qiu et al., 2019). The persistent gender gap in digital skill distribution continues to constrain rural women’s economic opportunities in the digital transformation. The GSMA estimates that closing the mobile internet gender gap in low- and middle-income countries between 2023 and 2030 could add $1.3 trillion to global GDP while generating an additional $230 billion in revenue for the mobile communications industry. This underscores the significant economic and social value of addressing the digital gender divide.

Non-agricultural employment for rural women represents a critical mechanism for advancing both poverty reduction and gender equality objectives. However, persistent multidimensional barriers continue to constrain its development. Individual-level constraints include limited educational attainment (Estudillo & Otsuka, 1999; D. P. Sun et al., 2022; H. Liu et al., 2025), occupational skill deficits (Pan et al., 2021), health challenges (J. F. Sun et al., 2024), and marital status considerations (Deng & Luo, 2025). Family-level factors encompass traditional gender role expectations (Z. H. Yang & Chen, 2024), caregiving responsibilities (Van et al., 2013; Taye & Tesfaye, 2024; D. Yang et al., 2025), and household structure characteristics (G. Y. Sun & Sun, 2022). Societal-level barriers feature prominently in the form of digital skill gaps within increasingly technology-driven economies (Ding et al., 2025). These intersecting challenges perpetuate a cyclical pattern of limited skills, constrained earnings, and restricted development opportunities (Chang & Zhang, 2025). Digital literacy emerges as a particularly valuable competency in this context due to its dynamic and upgradable nature. By enabling continuous skill adaptation to technological changes and facilitating access to more stable income streams through digital tools, digital literacy offers a viable pathway to break this persistent cycle and support sustainable improvements in employment quality (Xu, 2024).

Existing research has demonstrated digital literacy’s positive impact on rural women’s non-agricultural employment through multiple channels, including information channel expansion (Boateng et al., 2018; L. L. Zhou et al., 2024; Miao et al., 2024; Fang et al., 2025) and increased employment probability (Ruan & Luo, 2024). Emerging studies have begun to explore longer-term effects, such as digital skills’ association with employment stability (D. Zhou et al., 2024) and economic independence-induced family power structure reorganization (Aguilera et al., 2021). However, three critical gaps exist in this field of research, whose significance is underscored by deficiencies in the existing literature. First, theoretical frameworks lack integration. While most studies acknowledge the multidimensional nature of digital literacy (L. L. Li et al., 2025), they often examine these attributes in isolation. For instance, prior research clearly depicts device usage patterns, yet analyses fail to extend to the interaction between underlying cognitive skills and family support environments, resulting in fragmented perspectives (W. L. Jiang & Zhao, 2022). Second, mechanism studies exhibit pronounced narrow-mindedness. The existing literature thoroughly reveals the direct benefits of explicit pathways like skill training and expanding information channels (Chen & Weng, 2024), yet systematic research demonstrating the implicit mediating role of psychological capital remains extremely rare. Third, research on non-agricultural employment primarily focuses on overall non-agricultural employment (J. Wang & Han, 2023; F. Liu et al., 2024), with relatively few studies examining the impact of digital literacy on rural women’s non-agricultural employment. This gap hinders the provision of decision support for enhancing rural women’s non-agricultural employment capabilities in the digital economy era.

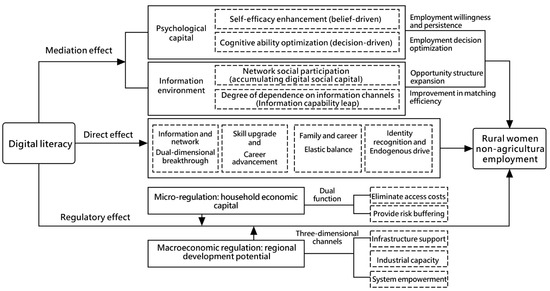

Building on social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977), this study constructs an analytical framework to examine the impact of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment among rural women and its underlying mechanisms through the dimensions of psychological capital and information environment. The framework specifically assesses long-term impacts on sustainable poverty reduction and gender equality outcomes.

This research makes three primary contributions. Firstly, it advances theoretical understanding by employing causal inference methods including instrumental variables to isolate digital literacy’s net effect on non-agricultural employment, thereby expanding social learning theory’s applications in digital economy contexts. Secondly, it elucidates the mechanisms fostering sustainable employment competitiveness through complementary psychological capital and information capability pathways. Thirdly, it proposes policy strategies that simultaneously address short-term needs and long-term capacity development. These integrated recommendations promote rural women’s high-quality employment while supporting poverty reduction, gender equity, and rural revitalization objectives, providing valuable guidance for global sustainable development initiatives.

The structure of this paper is as follows: after the introduction, the second part will describe the theoretical background related to digital literacy and rural women’s non-agricultural employment, and on the basis of which the research hypotheses will be formulated. The third part will present the research data and methodology, the fourth part shows the empirical results containing benchmark regression, robustness test, mechanism test, etc., and the fifth part elucidates the conclusion and recommendation, containing its limitations and future research plans.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Direct Impact of Digital Literacy on Non-Agricultural Employment Among Rural Women

Social learning theory emphasizes that individual capabilities serve as fundamental determinants of behavioral choices and development opportunities (Bandura & Walters, 1977). Digital literacy, which combines technological operation skills, information processing abilities, and social participation competencies, directly influences rural women’s transition to non-agricultural employment. This influence operates on multiple levels: it not only helps overcome immediate employment obstacles but also establishes foundations for sustainable development through persistent dynamic mechanisms. To comprehensively analyze this phenomenon, we integrate insights from digital empowerment theory (Dijk, 2005) and social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977), examining both short-term employment barrier reduction and long-term empowerment effects through a three-dimensional framework.

Firstly, digital technologies have transformed rural women’s access to employment opportunities by overcoming geographic and social barriers. Through mobile recruitment platforms and intelligent algorithms, they can now efficiently match with suitable jobs, while short videos and social media enable connections to broader professional networks. This dual advancement not only bypasses the limitations of traditional kinship-based information channels (Putnam, 2000) but also bridges gaps in digital literacy, granting access to diverse occupational models. These findings align with social learning theory, demonstrating how digitally mediated information shapes career decisions and creates sustained learning opportunities (X. Wang et al., 2023; Martínez-Nicolás et al., 2025). For instance, the process of transforming digital literacy into business acumen and practical skills significantly enhances the resilience and sustainability of women’s employment (Razzaq et al., 2024). This capacity building fundamentally elevates their long-term employment competitiveness and career control in the digital economy era.

Secondly, digital skill enhancement and professional development directly contribute to higher employment quality. Within the digital economy landscape, competencies in office software utilization and digital media management now constitute fundamental labor market prerequisites (Bejaković & Mrnjavac, 2020; Zhang et al., 2023). Rural women with digital literacy not only can overcome geographical and temporal constraints through e-commerce and digital inclusive finance (X. Yang et al., 2022) but can also leverage advanced digital capabilities such as data analysis and strategic optimization to effectively enhance employment security and broaden long-term career prospects. For instance, women equipped with cross-border e-commerce competencies can leverage global market trend analysis to optimize product strategies, thereby achieving sustainable income growth. This skillset advancement transcends traditional constraints imposed by both technical skill gaps and limited social capital, while simultaneously initiating a self-reinforcing cycle of enhanced employment quality and intergenerational resource accumulation (Aguilera et al., 2021).

Thirdly, digital literacy helps rural women balance family and work responsibilities more effectively, leading to more equitable gender roles while creating lasting empowerment through technology. Traditional gender roles often limit rural women’s job opportunities due to their heavy domestic workload (Connell, 2013). However, digital skills enable flexible work-from-home arrangements that overcome these barriers. Women can now care for their families while developing careers—not as a temporary solution, but through an ongoing process of learning and adaptation (Bandura & Walters, 1977) that gradually changes how households divide labor. This shift moves families away from traditional “male breadwinner” models toward more equal partnerships, helping break cycles of poverty while promoting gender equality across generations (Sen, 1999; Long et al., 2023; Tamang et al., 2025).

Fourthly, digital literacy enables lasting identity transformation and sustainable development. Rural women often face diminished self-efficacy due to entrenched domestic roles that conflict with digital-era skill demands (Hargittai, 2002; Debbarma & Chinnadurai, 2023). Through practical applications like creating digital content and managing network sales, digital literacy helps them develop professional identities as tech-savvy entrepreneurs. This facilitates a fundamental cognitive shift from reactive adaptation to proactive innovation (Mukherjee et al., 2024). The long-term impacts extend beyond individual career improvement. These transformed women become role models, creating ripple effects that help entire communities overcome employment barriers. This process generates self-sustaining rural development through a virtuous cycle where increased earnings enable education investments, which further enhance skills and opportunities (Tian & Li, 2024). Ultimately, such transformation advances both gender equality and rural revitalization objectives globally.

A comprehensive analytical framework has been constructed based on three dimensions: technology, structure, and individual. This framework integrates the “technology access” perspective of digital empowerment theory with the “sociocultural” perspective of social learning theory, while incorporating a dynamic analysis of digital literacy. It elucidates how digital literacy facilitates short-term employment transitions and catalyzes long-term empowerment. This integrated framework provides a more comprehensive theoretical toolkit for exploring non-agricultural employment among rural women. Building on this theoretical foundation, we propose:

Hypothesis 1.

Enhancing digital literacy can significantly increase non-agricultural employment opportunities for rural women.

2.2. The Indirect Mechanism of Digital Literacy on Non-Agricultural Employment Among Rural Women: A Dual-Path Analysis Based on Social Learning Theory and Digital Empowerment Theory

The triadic interaction model of social learning theory reveals the dynamic relationship among individual behavior, cognition, and environmental factors. This study constructs a dual-pathway framework based on social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977) and digital empowerment theory (Castells, 2011) to examine psychological capital formation and information environment transformation. This framework systematically explains how digital literacy overcomes structural constraints through dynamic mechanisms, with a particular focus on its role in promoting rural women’s employment.

2.2.1. Psychological Capital Dimensions: Mediation Through Self-Efficacy and Cognitive Ability

At the micro-level, digital literacy transforms psychological capital through two progressive mechanisms: belief reinforcement and decision optimization. Firstly, the self-efficacy pathway demonstrates intergenerational continuity. Through digital skills training and practical application, rural women develop mastery experiences that reduce technology-related anxiety while transmitting occupational confidence to subsequent generations via observational learning within families (Calderón et al., 2022). For instance, women proficient in e-commerce often become role models, gradually disrupting intergenerational cycles of poverty cognition (Sen, 1999; Lev-On et al., 2021). Secondly, the cognitive ability pathway follows a stage-based progression. Drawing on Piaget’s cognitive adaptation theory (Piaget & Inhelder, 2000), digital literacy initially disrupts traditional cognitive patterns through information assimilation, subsequently develops adaptive decision-making skills, and ultimately establishes lifelong learning capacities for the digital economy. This evolving cognitive advantage helps rural women avoid skill obsolescence and employment lock-in during industrial transitions (Kumar et al., 2024). Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Digital literacy promotes rural women’s non-agricultural employment through two complementary psychological capital pathways.

2.2.2. Information Environment Dimensions: Mediation Through Online Information Participation and Information Channel Reliance

Through an interactive transmission mechanism that combines online information participation with reliance on information channels, digital literacy facilitates the reconstruction of social capital and enhances digital capabilities. This enables rural women to transcend the constraints of the traditional-modern dichotomy, with its long-term effects exhibiting distinct phased characteristics. At the level of online information participation, digitally literate rural women exhibit a three-stage process of social capital development: initially leveraging platforms like short-video apps to transcend geographical constraints, expanding localized social networks (Putnam, 2000) into cross-regional digital communities (Sá et al., 2021); subsequently integrating into broader digital industry ecosystems through observational learning and practical engagement; and ultimately establishing sustainable knowledge-sharing communities that continuously generate new career opportunities (Chetty et al., 2018; J. Yang et al., 2024). This process preserves the core elements of trust and cooperation inherent in traditional social capital (Kabeer, 2005) while enabling intergenerational appreciation of social capital through sustained digital interaction, thereby constructing a durable and robust employment support system. Regarding information channel transformation, digital literacy facilitates dynamic skill-opportunity matching and exhibits a progressive impact pathway: in the short term, it manifests as enhanced information filtering capabilities to overcome temporal and spatial constraints (D. Zhou et al., 2024; Kodrat et al., 2024); in the medium term, it enables precise alignment with industry demands through data analysis; and in the long term, it fosters a resilient employment ecosystem where digital social capital and sustainable livelihoods are deeply integrated. For instance, rural women equipped with cross-border e-commerce skills can effectively mitigate market risks through real-time data analysis while expanding global business channels (Yu & Cui, 2019). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

Digital literacy promotes non-agricultural employment opportunities for rural women through synergistic mechanisms within the information environment dimension.

2.2.3. Family Economic Capital and Regional Development Potential: Long-Term Dynamic Effects of Dual-Level Regulation

The empowerment effect of digital literacy evolves dynamically through family-region coordination, forming a sustainable diffusion mechanism. At the micro-level of the household, disparities in family economic capital create divergent digital literacy trajectories. Economically advantaged households enable sustained investments in smart devices and advanced training, facilitating progression from basic tool use to strategic application (Gibson et al., 2024; Rohatgi & Gera, 2025). This generates intergenerational advantages through observational learning (Bandura & Walters, 1977), disrupting poverty cycles (Sen, 1999). Conversely, resource-constrained households often remain at basic operational levels due to limited reinvestment capacity, preventing the skill-income-reinvestment virtuous cycle and perpetuating low-skilled employment traps. At the regional level, developed regions amplify digital literacy’s impact through industrial diversification and robust infrastructure, where integrated 5G networks and public digital platforms reduce skill acquisition costs while scaling individual employment gains into collective entrepreneurship via e-commerce clusters (Y. Wang & Wu, 2025), thereby fostering regional development ecosystems. In contrast, underdeveloped regions exhibit fragmented outcomes; while digital literacy brings short-term income and employment improvements, institutional and infrastructure constraints hinder systemic employment transformation.

This dual-level analysis advances beyond traditional static frameworks by demonstrating how digital literacy converts short-term employment gains into lasting development momentum, transcending geographical limitations of social capital and technological access paradigms (Prayitno et al., 2022). It provides a dynamic model for understanding intergenerational employment quality improvement and regional gender equity advancement. Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

The effectiveness of digital literacy in promoting non-agricultural employment among rural women is moderated by household economic capital and regional development potential.

Building upon the preceding analytical framework, this study develops a comprehensive theoretical model, graphically represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Mechanism of Digital Literacy’s Impact on Rural Women’s Non-agricultural Employment.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

The data for this study are derived from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2014–2020 longitudinal survey data collected by the China Social Science Survey Center at Peking University. As a comprehensive national-level social tracking survey project, the CFPS employs a scientific sampling method combining stratified, multi-stage, and probability-proportional-to-size sampling, coupled with standardized questionnaire design, to systematically collect dynamic information at both the individual and household levels. The data quality has undergone rigorous validity and reliability testing and is widely utilized in academic research both domestically and internationally, demonstrating high authority and reliability.

This study is based on CFPS panel data from 2014 to 2020, focusing on rural women. Through a rigorous data screening and merging process, research subjects aged 16 to 65 were selected. The study used a standardized data cleaning program to systematically handle missing and abnormal values, ultimately obtaining 45,994 valid samples, laying a solid data foundation for subsequent empirical analysis.

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Non-Agricultural Employment Among Rural Women

This study utilizes data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) adult questionnaire to construct a binary dependent variable measuring rural women’s non-agricultural employment status. The variable selection process adheres to a three-tiered methodological approach. First, the target population is identified through rural residency and female gender criteria. Second, employment status is precisely operationalized using two key dimensions: engagement in non-agricultural work and active labor market participation. Respondents who simultaneously satisfy all four conditions—rural household registration, female gender, non-agricultural employment, and active employment status—are coded as 1, with all others coded as 0. This rigorous operationalization ensures sample homogeneity, establishes clear research boundaries, and provides robust data for empirical analysis.

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable: Digital Literacy

This study conceptualizes digital literacy as a multidimensional competency encompassing an individual’s ability to utilize digital technologies for information acquisition, learning, communication, and commercial engagement. Referring to Wang Jie’s theoretical framework (J. Wang et al., 2022), this construct is operationalized through five distinct dimensions: device operation, digital learning, network socialization, Online shopping, and digital entertainment, the specific indicators selected are listed in Table 1. Each dimension is measured using binary indicators that assess specific behaviors including mobile or computer internet access, network learning activities, social media usage, online shopping and digital entertainment consumption. The comprehensive digital literacy index is calculated by weighting five dimensional indicators using the entropy weighting method. This methodology minimizes subjective bias in weight assignment while ensuring statistical robustness, ultimately producing a continuous standardized index where higher values correspond to greater digital literacy proficiency among rural women respondents.

Table 1.

Digital literacy measurement indicator system.

3.2.3. Control Variables

This study addresses potential confounding factors in the analysis of rural women’s non-agricultural employment by selecting control variables from three key domains based on Wang Hanjie et al.’s framework (H. J. Wang, 2024). The individual characteristics domain includes age measured as a continuous variable, educational attainment coded on a four-point ordinal scale ranging from illiterate or semi-literate to associate degree or higher, marital status categorized as married versus unmarried including cohabiting divorced or widowed, and self-reported health status assessed through a five-point Likert scale. The household circumstances domain includes household size, logarithmically transformed annual household expenditure, number of children under 16, and number of elderly household members aged 65 and above. All variables are operationalized using direct questionnaire items to ensure consistency with the original data collection protocol while maintaining methodological rigor in controlling for potential confounding effects between digital literacy and employment outcomes.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

This study examines the pathways through which digital literacy influences rural women’s non-agricultural employment by analyzing two key dimensions: psychological capital and information environment. Within the psychological capital dimension, Within the psychological capital dimension, a 5-point Likert scale was employed to measure “confidence in one’s future.” A score of 1 indicates no confidence, while 5 signifies strong confidence. Higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy in personal capabilities and career decision-making. Cognitive ability is operationalized through intellectual level assessments, capturing individuals’ capacity to interpret labor market signals and optimize career strategies. The information environment dimension incorporates two variables: dependence on information channels, quantified using a 5-point scale measuring perceived importance of internet-sourced information following Chen Li’s methodology (Chen & Weng, 2024), and network social participation, assessed through weekly frequency of accessing political information network. These measures collectively evaluate both the efficiency of digital resource utilization and depth of network engagement, which shape employment-related information acquisition and policy awareness. The selected variables provide comprehensive coverage of the theorized mechanisms while maintaining strong correspondence with established theoretical frameworks and empirical measurement approaches. The variables used in this paper are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Definitions of main variables and descriptive statistical results.

3.2.5. Regulatory Variables

This study examines the contextual factors shaping digital literacy’s impact on rural women’s non-agricultural employment by incorporating household economic capital and regional development potential as moderating variables, capturing both micro-level resource foundations and macro-level environmental supports. Household economic capital is operationalized as the logarithm of per capita household net income, reflecting theoretical expectations that greater economic resources enable investments in digital devices and skill training that facilitate the translation of digital competencies into employment outcomes. Regional development potential is measured through city-level GDP, representing the concentration of non-agricultural employment opportunities, digital infrastructure quality, and technological application environments that collectively enhance digital literacy’s employment benefits. These moderators allow for systematic analysis of how varying resource endowments and institutional contexts differentially influence the relationship between digital literacy and labor market outcomes.

3.3. Model Design

3.3.1. Regression Model Construction

This study develops a panel data model to empirically examine the effects of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment outcomes among rural women.

Yit = α0 + α1Digitalit + βXit + μi + γi + εit

Among these, the dependent variable Yit represents the non-agricultural employment status of individual i in year t; the core explanatory variable Digitalit is the comprehensive digital literacy index of individual i in year t; Xit is the control variable related to the individual; μi is the provincial dummy variable; Yit is the time dummy variable; and εit is the random disturbance term.

3.3.2. Mechanism Validation Model

To further explore the underlying mechanisms through which digital literacy influences non-agricultural employment among rural women, this study builds upon Model (1) and, following Jiang Ting’s framework for testing mediating effects (T. Jiang, 2022), constructs the following mechanism verification model:

Mit = α0 + α1Digitalit + βXit + μi + γi + εit

Among these, Mit represents the instrumental variable. All other variables and coefficients are defined consistently with Model (1). By comparing the estimation results of Models (1) and (2), we can systematically deconstruct the transmission mechanism through which digital literacy influences non-agricultural employment via different mediating pathways.

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

The two-way fixed effects model reveals that digital literacy significantly enhances rural women’s non-agricultural employment, with coefficients consistently ranging from 0.016 to 0.059 across specifications (p < 0.01) in Table 3, confirming hypothesis H1. After controlling for provincial and time fixed effects and treating individuals as clusters, this effect remains robust, indicating that digital literacy is a key factor in promoting women’s non-agricultural employment.

Table 3.

Baseline Regression Results.

Analysis of individual characteristics reveals notable structural patterns. Age exhibits a pronounced negative association, reflecting service-sector demands for physical capacity and adaptability that disadvantage older workers despite digital skill compensation. Educational attainment, health status, and digital literacy exhibit synergistic effects, with higher education and better health facilitating skill conversion and career advancement. Married women face significant employment barriers due to caregiving responsibilities that fragment time availability (S. Y. Liu & Luo, 2024).

Family characteristics demonstrate dual constraint mechanisms through distinct pathways. Households with larger populations may opt for non-agricultural employment to secure additional income due to the pressures of daily life. Higher household expenditure reduces employment necessity via wealth effects, thereby diminishing the marginal utility of digital literacy. Regarding family caregiving responsibilities, the obligations to support elderly parents and raise children consistently suppress employment probabilities (Gao, 2025). These findings pinpoint specific policy intervention opportunities that could optimize the employment benefits derived from digital literacy.

4.2. Robustness Test Results

To validate the reliability of the regression findings, this study examines the stability of digital literacy’s impact on rural women’s non-agricultural employment through four robustness checks.

4.2.1. Exclusion of 2020 Samples

The COVID-19 pandemic induced systemic shocks across rural non-agricultural labor markets, particularly affecting service sector industries (J. F. Sun et al., 2024). To isolate potential confounding effects from this exceptional event, the analysis was replicated after excluding 2020 observations.

Table 4 demonstrates that digital literacy retains its robust positive effect on employment outcomes even after removing pandemic-related disturbances. This persistence confirms that digital literacy’s empowering function operates independently of transient macroeconomic conditions, instead reflecting its fundamental role in enhancing rural women’s employability and providing sustainable labor market resilience. The results substantiate digital literacy as an enduring capacity-building mechanism rather than a context-dependent phenomenon.

Table 4.

Robust tests 1 and 2.

4.2.2. Alternative Specification of Dependent Variable

The robustness assessment involved redefining the measurement of non-agricultural employment through expanded classification criteria. Table 4 Results in demonstrate that the positive association between digital literacy and employment outcomes remains statistically significant under broader operationalization. This persistence highlights digital literacy’s inclusive empowerment properties. The findings indicate that digital literacy effectively supports diverse employment forms across heterogeneous groups of rural women.

4.2.3. Winsorization Treatment

A 5% winsorization procedure was applied to all continuous variables to address potential bias from extreme observations. Table 5 shows that digital literacy retains its significant positive effect on non-agricultural employment after excluding outliers in income and expenditure distributions. This robustness confirms that the observed empowerment effects represent fundamental capacity-building mechanisms rather than artifacts of extreme values, demonstrating notable resilience to data noise and supporting the stability of sustainable employment outcomes.

Table 5.

Robust tests 3 and 4.

4.2.4. Modify Core Variable Measurements

Based on previous research (Luo & Mo, 2025; R. Li et al., 2025), replacing the entropy method with factor analysis for measuring digital literacy yielded a KMO value of 0.675 (greater than 0.6) and Bartlett’s test p = 0.000 (less than 0.05), confirming the suitability of factor analysis.

As shown in Table 5, after changing the measurement method, digital literacy still significantly positively influences non-agricultural employment among rural women at the 1% statistical level.

4.3. Endogeneity Test Results

Potential reverse causality and omitted variable bias may lead to spurious correlations between non-agricultural employment and digital literacy in Table 2. To establish robust causal inference, this study employs instrumental variable (IV) estimation and Heckman’s two-stage approach.

4.3.1. Instrumental Variable Approach

The Results of the instrumental variable approach are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results of the instrumental variable approach.

Following the methodology of digital literacy-related literature (Huang et al., 2019), an instrumental variable was constructed using historical urban telephone data from 1984. Specifically, this instrumental variable is derived by taking the natural logarithm of the interaction term between “the number of internet users nationwide in the previous year multiplied by the number of telephones in 1984.” The rationale is as follows: In terms of correlation, the penetration rate of telephones during the early stages of reform and opening-up effectively reflects the development level of regional communication infrastructure. Communication infrastructure serves as the foundation for digital economic development and exhibits a significant association with contemporary digital literacy levels. Regarding exogeneity, the historical communication data from 1984, used as an exogenous variable, is unaffected by contemporary economic shocks and uncorrelated with the model’s error term, thus satisfying the exogeneity requirement for instrumental variables. This instrumental variable design helps effectively control potential endogeneity issues and enhances the robustness of estimation results.

The two-stage least squares analysis yielded key empirical findings, jointly establishing robust causal evidence. The first-stage results indicate a statistically significant positive correlation between the instrumental variable and the endogenous dependent variable at the 1% significance level, supporting the theoretical expectation that improvements in regional internet infrastructure facilitate the acquisition of digital skills. The second-stage estimates in Table 6 show that, after addressing endogeneity issues, digital literacy continues to exert a statistically significant positive impact on employment outcomes at the 1% significance level, confirming its causal effect on labor market participation. Diagnostic tests validated the empirical methodology: the unidentifiability test yielded a p-value below 0.01, and the F-statistic exceeded the 10% threshold (16.38). Model identification at the 0.1% significance level confirms the absence of weak instrumentation issues. Collectively, these findings provide robust evidence that digital literacy significantly enhances rural women’s employment prospects, unaffected by reverse causality or omitted variable bias. This establishes digital empowerment as an effective human capital development strategy for sustainable economic growth.

4.3.2. Heckman Two-Stage Analysis

Sample selection bias may introduce endogeneity when examining how digital literacy affects rural women’s non-agricultural employment, potentially distorting estimation accuracy. The Heckman two-stage method addresses this concern to ensure robust conclusions.

In the first stage, the interaction term between the previous year’s national internet user count and the 1984 telephone count was employed as an instrumental variable, representing the level of regional digital infrastructure development. This macro-level indicator captures how local digital ecosystems influence individual behavior. The results in Table 7 demonstrate this instrument’s significantly positive coefficient at the level of 1%, confirming its validity. Areas with advanced digital infrastructure show greater individual access to digital technologies and higher propensity for non-agricultural employment participation, consistent with sustainable development’s digital ecosystem equity principles.

Table 7.

Heckman two-stage analysis results.

The second stage incorporates the inverse Mills ratio to correct selection bias. The significantly negative IMR coefficient reveals crucial methodological insights: unobserved heterogeneity in occupational skills and employment intentions simultaneously affects both sample selection and the digital literacy-employment relationship. Without correction, such factors could inflate digital literacy’s estimated effects, as more capable and motivated individuals typically exhibit both higher digital proficiency and employment rates. The IMR adjustment successfully isolates these confounding influences, yielding more accurate causal estimates of digital literacy’s true employment impact. This methodological refinement provides reliable evidence for designing digital empowerment policies that promote sustainable employment among rural women.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test Results

The enabling effect of digital literacy on rural women’s non-agricultural employment demonstrates significant variation across different socioeconomic contexts. This study examines heterogeneity through four key dimensions to identify boundary conditions and inform targeted policy interventions.

4.4.1. Regional Heterogeneity

This study examines regional differences in how digital literacy affects rural women’s non-agricultural employment. Using regional economic gradient theory, we analyze provincial data from eastern, central, and western China through grouped regression analysis. Table 8 results indicate that the positive impact of digital literacy is most pronounced in western regions. This regional advantage stems from three key factors: First, influenced by national policies, western regions’ economic development and digital infrastructure have created ideal conditions for technology-driven employment growth. Second, rural women in these areas effectively leverage digital platforms to overcome geographical constraints and efficiently access suitable job opportunities. Third, unlike the diversified industries in eastern and central regions that dilute the employment effects of digital technologies, the growth trajectory in western regions unleashes the potential of digital empowerment. These structural differences explain why digital literacy promotes employment more effectively in western regions than elsewhere. The findings highlight how local economic conditions shape the role of technology in rural labor markets.

Table 8.

Heterogeneous test results 1 and 2.

4.4.2. Age Heterogeneity

This study examines digital literacy’s employment effects across three age cohorts of rural women, revealing significant intergenerational differences. The results in Table 8 show that digital literacy most strongly promotes non-agricultural employment among women aged 16–35, particularly those who came of age during China’s digital transformation period, as their cognitive adaptation and technical proficiency enable efficient utilization of digital tools for flexible work opportunities. In contrast, women aged 36–65 experience limited employment benefits due to lower educational attainment, heavier family care burdens, and greater challenges in digital skill acquisition, constraining their ability to translate digital literacy into labor market advantages. These findings underscore how life-cycle factors—including technological exposure, human capital, and caregiving responsibilities—shape the effectiveness of digital empowerment in rural labor markets.

4.4.3. Household Size Heterogeneity

This study divided the sample into three groups based on household size: small households (1–6 people), medium-sized households (7–10 people), and large households (11 or more people) to examine the heterogeneous effects of digital literacy.

The results in Table 9 reveal distinct patterns across household sizes. In small households, concentrated resources facilitate greater access to digital devices and training, enabling women to efficiently match with employment opportunities through digital platforms. Medium households benefit from established labor collaboration and information-sharing networks, where digital literacy enhances employment outcomes through collective learning. In contrast, large households face resource dispersion and disproportionate caregiving burdens, which constrain time for digital skill development and application, ultimately limiting employment gains. These findings demonstrate how intra-household resource allocation and labor dynamics shape the effectiveness of digital literacy in rural labor markets.

Table 9.

Heterogeneous test results 3 and 4.

4.4.4. Educational Heterogeneity

This study examines how educational background influences digital literacy’s impact on rural women’s employment by comparing two groups: low educational attainment (junior high school or below) and high educational attainment (high school or above). The results in Table 9 reveal distinct mechanisms across education levels. For less-educated women, digital literacy compensates for educational disadvantages by overcoming information barriers, demonstrating strong employment-promoting effects. In contrast, among more-educated women with stronger human capital foundations, the marginal employment benefits of basic digital skills are reduced. This group requires advanced skill development, particularly in areas like data analysis and cross-border e-commerce operations, to achieve meaningful employment gains. These findings highlight how educational attainment shapes the pathway through which digital literacy influences labor market outcomes, suggesting the need for differentiated skill development approaches.

4.5. Mediating Effect Test

This study investigates the transmission mechanisms of digital literacy through a dual-pathway framework encompassing psychological capital and information environment dimensions. The analysis focuses on four core pathways: self-efficacy, cognitive ability, network social participation, and information channel dependency. The psychological capital dimension examines how digital literacy fosters endogenous empowerment by enhancing employment confidence and cognitive decision-making capabilities. The information environment dimension explores how digital technologies reshape employment information ecosystems and social network resources. Together, these dimensions elucidate the fundamental mechanisms through which digital literacy promotes non-agricultural employment among rural women.

4.5.1. Psychological Capital Mediation: Self-Efficacy Pathway

The results in Table 10 confirm the mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between digital literacy and non-agricultural employment, supporting hypothesis H2. The data indicate that digital literacy significantly enhances both employment outcomes and employment confidence at the 1% significance level. This relationship establishes a reinforcing cycle where digital skill acquisition strengthens self-efficacy, which in turn facilitates employment behavior transformation. Specifically, rural women with computer operation and network information processing skills develop successful experiences through digital job search and remote work matching. These positive experiences reinforce their belief in achieving employment through digital means. When self-efficacy reaches critical levels, employment behaviors evolve from passive waiting to active pursuit, manifested through participation in digital skills training or exploration of new occupational roles such as cross-border e-commerce support. This psychological-skill-employment synergy demonstrates how psychological capital regulates employment behavior while revealing how digital literacy, by cultivating intrinsic motivation, provides psychological foundations for sustainable employment. The findings help explain how digital interventions can disrupt the negative cycle of low confidence leading to low labor market participation.

Table 10.

Psychological capital dimension mechanism results.

4.5.2. Psychological Capital Mediation: Cognitive Ability Pathway

The regression results in Table 10 confirm cognitive ability’s mediating role between digital literacy and employment outcomes, supporting hypothesis H2. Digital literacy significantly enhances both non-agricultural employment probability at the 1% level and cognitive ability at the 5% level, establishing a transmission mechanism from digital skills to cognitive enhancement to employment quality improvement. This cognitive progression follows an efficiency-application pattern, where rural women with digital skills demonstrate stronger logical reasoning and information integration capabilities, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of cognitive development. These advantages help overcome low-skill employment traps through better industry analysis and career planning, facilitating upward mobility in employment quality. The results highlight cognitive ability’s critical role in sustainable career development.

4.5.3. Information Environment Mediation: Information Channel Dependence Pathway

Table 11 results substantiate information channel dependence as a meaningful mediator, supporting hypothesis H3. Digital literacy influences employment outcomes through dual pathways: direct effects on employment probability and indirect effects through improved information utilization capabilities. This mediation transforms how rural women interact with employment information, converting overwhelming data streams into targeted resource pools. Women proficient in digital skills effectively employ modern tools like smart algorithms and specialized databases to achieve precise job matching. By developing these information processing competencies, they gain measurable advantages in converting information access into concrete employment opportunities while simultaneously reducing job search costs and improving decision quality.

Table 11.

Information environment dimension mechanism results.

4.5.4. Information Environment Mediation: Network Information Pathway

Table 11 analysis confirms network information participation functions as a significant mediator, supporting hypothesis H3. Digital literacy simultaneously enhances employment outcomes and digital community engagement, establishing an integrated skills–social capital–opportunities pathway. This mediation enables innovative forms of social capital accumulation through active participation in social media platforms and professional network communities. Such digital engagement helps overcome traditional geographical constraints and gender barriers in employment access. The resulting expansion of network resources facilitates a crucial transition from isolated individual job seeking to collaborative collective development, with demonstrated improvements in both employment stability and long-term career potential.

4.6. Moderating Effect Test

4.6.1. The Moderating Effect of Household Economic Capital

Household economic capital moderates digital literacy’s employment impact through dual mechanisms of economic pressure transmission and career decision constraints. The empirical results in Table 12 demonstrate that per capita household net income’s interaction term shows significant positive moderation at the 1% level, indicating stronger digital literacy effects in economically advantaged households. Economically constrained households impose rigid requirements on women’s employment choices, limiting them to low-skill, immediate-income jobs with minimal digital skill demands. In these circumstances, digital literacy’s employment benefits remain suppressed as economic survival takes precedence over skill development. Conversely, economically secure households enable women to pursue career development based on interests, skills, and long-term potential. This environment fosters selection of digitally intensive occupations where skills can be fully utilized and progressively enhanced through positive feedback between application and advancement. The resulting occupational differentiation reveals how household resources fundamentally shape employment decision-making processes and digital literacy’s effectiveness.

Table 12.

Results of the moderating effect of household economic capital.

4.6.2. The Moderating Effect of Regional Economic Potential

Regional economic potential moderates digital literacy’s effects through synergistic digital infrastructure and socio-cultural mechanisms. County and year fixed effects are employed in Table 13. Digital literacy levels may vary across different years within the same county, and such variations influence rural women’s non-agricultural employment. The interaction term between digital literacy and prefecture-level city GDP indicates that in counties with higher regional economic potential, the positive impact of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment is weakened. This implies that for within-individual variation, the effect of digital literacy depends on changes in economic potential. Intra-individual variation primarily stems from changes over time in digital literacy, regional economic potential, and their interaction within the same county. These shifts drive fluctuations in rural women’s non-agricultural employment. After controlling for all variables, rural women’s non-agricultural employment exhibits a baseline level. Combining moderation effects, the flow pattern reveals that in economically underdeveloped regions, digital literacy serves as the key driver of non-agricultural employment, whereas in economically advanced regions, other factors (such as internet access and policies) may play a more significant role.

Table 13.

Results of the moderating effect of regional economic potential.

Table 13 employs county and year fixed effects. Digital literacy levels may vary across different years within the same county, and such variations influence rural women’s non-agricultural employment. The interaction term between digital literacy and prefecture-level city GDP indicates that in counties with higher regional economic potential, the positive impact of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment is weakened. This implies that for within-individual variation, the effect of digital literacy depends on changes in economic potential. Intra-individual variation primarily stems from changes over time in digital literacy, regional economic potential, and their interaction within the same county. These shifts drive fluctuations in rural women’s non-agricultural employment. After controlling for all variables, rural women’s non-agricultural employment exhibits a baseline level. Combining moderation effects, the flow pattern reveals that in economically underdeveloped regions, digital literacy serves as the key driver of non-agricultural employment; whereas in economically advanced regions, other factors (such as internet access and policies) may play a more significant role.

5. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

This study employs a social learning theory perspective and utilizes a two-way fixed-effects model to systematically analyze data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2014 to 2020, investigating how digital literacy influences non-agricultural employment among rural women. Findings reveal that digital literacy significantly enhances non-agricultural employment outcomes, though its effectiveness varies across regions, age groups, household sizes, and educational attainment. This indicates that digital literacy, as a transformative human capital asset, not only helps overcome structural employment barriers but also highlights the influence of contextual factors. Mechanism analysis reveals dual empowerment pathways: psychological capital development enhances employment confidence and career decision-making by boosting self-efficacy and cognitive abilities; information environment optimization strengthens resource acquisition and integration capabilities through expanded digital social participation and improved information channel utilization. Additionally, household economic capital and regional development potential emerge as key moderating variables—household resources determine skill acquisition opportunities, while regional conditions shape skill application scenarios, jointly influencing the effectiveness of digital literacy in translating into non-agricultural employment advantages.

Although this study systematically examined the impact of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment among rural women and its underlying mechanisms, the following limitations remain: First, the measurement method for digital literacy may have certain limitations. While this study constructed a composite indicator for digital literacy, this indicator still relies on a limited set of items from the China Family Panel Studies questionnaire, failing to fully capture the multidimensional nature of digital literacy. Future research may consider collecting richer primary data through field surveys to enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of measurement indicators. Second, although this study utilized the 2014–2020 CFPS panel data, data continuity remains insufficient. Access to longer-term, higher-frequency longitudinal data in future research would better confirm the dynamic causal relationship between digital literacy and non-agricultural employment. Third, the sample selection scope remains limited. This study focuses on rural women; subsequent research could broaden the sample scope to conduct cross-group comparisons, thereby gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the role of digital literacy in the labor market.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

This study proposes comprehensive policy recommendations in the following five areas in order to further promote the implementation of policies and enhance rural women’s capacity for off-farm employment and sustainable development in the digital economy:

First, a comprehensive “Tiered Digital Literacy Enhancement Program” should be implemented to establish a scientifically structured tiered training and targeted support system. This program must conduct precise group selection based on rural women’s age, educational background, and employment intentions, prioritizing coverage for those aged 16 to 45 with at least a junior high school education and clear non-agricultural employment aspirations. A simplified training pathway focused on short video applications, digital payments, and social marketing should be established for women aged 46 and above. Training content should be systematically advanced, progressing from foundational device operation and internet access to e-commerce operations, remote collaboration tools, and basic data analysis. Advanced courses covering platform management, digital compliance, and market strategy should be offered to those with entrepreneurial potential. It is recommended that county-level human resources departments lead the development of modular curricula in collaboration with vocational institutions and major digital enterprises to achieve sustainable empowerment through teaching individuals how to fish.

Second, establish an integrated social support system combining employment and childcare to effectively alleviate the family care burdens faced by rural women participating in training and employment. It is recommended to set up temporary childcare centers at township training centers and areas with high concentrations of female employment, providing free childcare services during training hours. Additionally, rural women who have secured non-agricultural jobs should receive monthly childcare subsidies ranging from 200 to 400 yuan, which should be incorporated into local employment support funds. Furthermore, actively guide community organizations to develop neighborhood mutual-aid childcare models. Coordinated by women’s federations or village committees, these arrangements would involve rotating childcare duties, forming low-cost community-based parenting support networks. This approach would free up rural women’s time and energy, unlocking their employment potential.

Third, to promote regional coordination and industrial integration, it is recommended to establish “Rural Women’s Digital Employment Incubation Centers” at the county level. These centers should integrate functions such as skills training, job matching, entrepreneurship incubation, and resource linkage. Operated jointly by governments, universities, and digital enterprises, they should focus on emerging sectors like rural e-commerce, digital agritourism, and remote services, providing end-to-end services from skill enhancement to actual employment. Clear, quantifiable targets should be established, such as training 500,000 rural women within three years, increasing non-agricultural employment rates by 5 to 8 percentage points, and successfully incubating at least 10,000 micro-enterprises led by rural women—including online stores and digital cooperatives. This will foster a virtuous cycle of digital employment that connects talent, industry, and regional development.

Fourth, a scientific dynamic monitoring and policy evaluation mechanism should be established, integrating digital literacy indicators with employment quality metrics into the rural revitalization performance evaluation system. Leveraging authoritative databases such as the China Panel Study, a multidimensional assessment framework encompassing digital literacy levels, non-agricultural employment stability, income growth rates, and career development trajectories should be developed. Regular publication of the Rural Women’s Digital Employment Development Report would provide evidence-based support for policy refinement and regional implementation. This approach facilitates a systemic shift from short-term employment promotion to long-term career development, thereby advancing the dual missions of gender equality and decent work within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Fifth, while advancing digital empowerment, it is imperative to prioritize and systematically address algorithmic bias, information harassment, and data privacy risks within cyberspace. It is recommended that all digital training programs incorporate a mandatory module on “Digital Security and Rights Protection”, covering personal information safeguards, strong password creation, and anti-fraud techniques. Dedicated sessions should guide participants in recognizing potential gender and regional biases in platform algorithms and mastering appeal and feedback mechanisms. Additionally, collaboration with cyberspace administration and public security departments should establish a “Green Channel for Rural Women’s Online Rights Protection”. This channel would provide rapid reporting and legal aid services for cyber harassment and data misuse, ensuring rural women gain self-protection capabilities as they access the digital world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and X.F.; methodology, S.P. and X.F.; software, S.P. and X.F.; validation, S.P. and X.F.; formal analysis, S.P. and X.F.; investigation, S.P. and X.F.; resources, S.P. and X.F.; data curation, S.P. and X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and X.F.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and X.F.; visualization, S.P. and X.F.; supervision, S.P. and X.F.; project administration, S.P. and X.F.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation Project of China [Grant No. 24CJY101; 21CJY001], Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission [Grant No. KJQN202300545], Higher Education Science Research Project of Chongqing Higher Education Society [Grant No.: CQGJ21B029], and Chongqing Municipal Education Science Planning Project [K25ZG2050043].

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/sjzx/gksj/index.htm (accessed on 26 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilera, F. J. G., Olivencia, J. J. L., Fontoura, E. E., & Fontoura, F. A. P. (2021). Social inclusion of rural women through digital literacy programs for employment. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(1), 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bejaković, P., & Mrnjavac, Ž. (2020). The importance of digital literacy on the labour market. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(4), 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, A., Asongu, S., Akamavi, R., & Tchamyou, V. (2018). Information asymmetry and market power in African banking industry. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 44, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D., Ortí, A. S., & Kuric, S. (2022). Self-confidence and digital proficiency: Determinants of digital skills perceptions among young people in Spain. First Monday, 27(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. A. (2011). Network theory of power. International Journal of Communication, 5(1), 773–787. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. Y., & Zhang, J. B. (2025). The impact of women’s livelihood choices on rural household cooking energy consumption: A case study of Hubei province. Resource Science, 47(04), 742–756. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., & Weng, Z. L. (2024). The impact of digital literacy on the employment quality of rural female labor. Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, (4), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, K., Aneja, U., Mishra, V., Gcora, N., & Josie, J. (2018). Bridging the digital divide in the G20: Skills for the new age. Economics, 12(1), 20180024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. (2013). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Debbarma, A., & Chinnadurai, A. S. (2023). Empowering women through digital literacy and access to ICT in Tripura. Research Journal of Advanced Engineering and Science, 9(1), 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X. J., & Luo, B. L. (2025). Is later better? The impact of age at first marriage on non-agricultural employment among rural women. Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, (05), 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijk, J. V. (2005). The deepening divide: Inequality in the information society. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S. L., Zou, T., & Liu, C. H. (2025). An empirical study on the impact of digital skills on gender wage gaps. Labor Economics Review, 18(01), 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Eshet, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 9(2), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estudillo, J. P., & Otsuka, K. (1999). Green revolution, human capital, and off-farm employment: Changing sources of income among farm households in Central Luzon, 1966–1994. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(3), 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S. L., Huang, Z. H., & Xu, X. N. (2025). The inclusive growth effects of digital financial development: A perspective on farmers’ non-agricultural entrepreneurship. Agricultural Technology Economics, (02), 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M. F. (2025). The impact of family care burdens on farmers’ land transfer behavior: A perspective on intergenerational and gender division of labor. Agricultural Technology Economics, (03), 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E. C., Gazi, S., & Arner, D. W. (2024). Digital finance, financial inclusion and gender equality: Strategies for economic empowerment of women. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, 46(1), 189–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster, P. (1997). Digital literacy. Wiley Computer Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monda, 7(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q. H., Yu, Y. Z., & Zhang, S. L. (2019). Internet development and manufacturing productivity enhancement: Internal mechanisms and Chinese experience. China Industrial Economics, (08), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. (2022). Mediating and moderating effects in empirical studies of causal inference. Chinese Industrial Economics, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W. L., & Zhao, X. (2022). Can internet use mitigate labor wage distortion?—Evidence from CFPS data. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 36(02), 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Gender and Development, 13(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodrat, D. S., Tambunan, D. B., & Hartono, W. (2024). Investigation of workplace literacy in Indonesia to enhance employability opportunities. Decision Science Letters, 13(2), 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Kumar, V., & Devi, N. (2024). Digital literacy: A pathway toward empowering rural women. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-On, A., Steinfeld, N., Abu-Kishk, H., & Pearl Naim, S. (2021). The long-term effects of digital literacy programs for dis-advantaged populations: Analyzing participants’ perceptions. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 19(1), 146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. L., Xu, J., Mei, Y., & Zeng, Y. W. (2025). The impact of digital literacy on farmers’ entrepreneurial decision-making: Empirical evidence from the China family panel studies. Journal of Agricultural and Forestry Economics and Management, 24(02), 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Chen, X., & Wei, D. (2025). Digital literacy and elderly household consumption: Micro evidence and influencing mechanisms. Guangxi Social Sciences, (04), 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F., Zhang, T. L., & Huang, P. (2024). Has digital inclusive finance improved income inequality?-Based on the Perspective of Non-agricultural Employment Transfer of Skilled Labor. Southern Finance, (06), 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Chen, H., & Wang, F. (2025). Has the development of digital villages enhanced farmers’ sense of fulfillment, happiness, and security? World Agriculture, (01), 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Y., & Luo, B. L. (2024). Does tutoring promote non-agricultural employment among rural women? Evidence from rural mothers in China. China Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition), 41(05), 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T. Q., Hoang, T. C., & Simkins, B. (2023). Gender gap in digital literacy across generations: Evidence from Indonesia. Finance Research Letters, 58, 104588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., & Mo, D. S. (2025). The impact of farmers’ digital literacy on the adoption of conservation tillage practices: An analysis based on CLES data. Chinese Journal of Agricultural Machinery and Chemistry, 46(08), 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A., & Grudziecki, J. (2006). DigEuLit: Concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, 5(4), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Nicolás, M., Catalina-García, B., & García-Galera, M. D. C. (2025). Access to the labour market in the digital society: The use and assessment of employment websites. Revista Latina de Comunicacion Social, 83, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y., Liu, Y., & Yin, Y. H. (2024). Enhancing digital literacy and promoting common prosperity: “Wealth” or “sharing”? Quantitative Economic Research, 15(04), 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, T., Ilavarasan, P. V., & Kar, A. K. (2024). Empowering through digital skills training: An empirical study of poor unemployed working-age women in India. Information Technology for Development, 30(3), 562–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M. M., Cai, S. K., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Does internet use promote non-agricultural employment among rural women? An empirical study based on survey data from four provinces: Jiangsu, Anhui, Henan, and Hubei. Agricultural Technology Economics, (08), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (2000). The psychology of the child. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Prayitno, P. H., Sahid, S., & Hussin, M. (2022). Social capital and household economic welfare: Do entrepreneurship, financial and digital literacy matter? Sustainability, 14(24), 16970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z. Q., Zhang, S. Q., Liu, S. D., & Li, G. H. (2019). From the digital divide to dividend disparity: A perspective from internet capital. Social Sciences in China, 40(01), 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq, A., Qin, S., Zhou, Y., Mahmood, I., & Alnafissa, M. (2024). Determinants of financial inclusion gaps in Pakistan and implications for achieving SDGs. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 13667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, S., & Gera, N. (2025). The augmenting role of digital banking in reconstructing women’s economic empowerment. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(2), 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R. H., & Luo, M. Z. (2024). Digital literacy, employment capacity, and non-agricultural employment of rural labor force. Hunan Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition), 25(04), 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sá, M. J., Santos, A. I., Serpa, S., & Ferreira, C. M. (2021). Digital literacy in digital society 5.0: Some challenges. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 10(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. P., Sun, Z. Y., Yu, B. T., & Li, Y. (2022). Has non-agricultural employment improved the well-being of rural residents? Southern Economy, (03), 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G. Y., & Sun, Y. P. (2022). The policy effects of rural women’s employment in China: A perspective based on labor transfer and release. Labor Economics Research, 10(05), 114–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. F., Wei, J. X., & Du, F. L. (2024). The buffering effect of agriculture on non-agricultural unemployment under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A re-examination of the labor pool function of agriculture. Chinese Rural Economy, (11), 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, S., Mishra, A., Vishwakarma, A., & Yadav, A. (2025). Impact of digital literacy on women empowerment with special reference to Uttar Pradesh, India. Abhigyan, 09702385251379161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye, T. T., & Tesfaye, W. M. (2024). Time poverty and women’s participation in non-agricultural work: Evidence from rural Ethiopia. Scientific African, 26, e02343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. P., & Li, J. Q. (2024). Can digital literacy alleviate female over-education—Evidence based on household tracking survey data. Journal of Shanxi University of Finance and Economics, 46(04), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. J. (2024). Digital literacy and farm household income: A discussion on the form of digital inequality. Chinese Rural Economy, (03), 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Cai, Z. J., & Ji, X. (2022). Digital literacy, rural entrepreneurship, and relative poverty alleviation. E-Government, 8, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Han, Y. (2023). A study on the impact of Internet use on non-agricultural employment of rural labor—Theoretical mechanism and micro evidence. Economic Issues, (09), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Yi, F., & Yang, C. (2023). “Promoting employment, supporting intelligence first”: The impact of digital literacy on non-agricultural employment of rural labour. Applied Economics Letters, 31(19), 2020–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Wu, Y. (2025). Digital economy, rural e-commerce development, and farmers’ employment quality. Sustainability, 17(7), 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. F. (2024). Digital literacy empowering remote work expectations: An empirical study based on the China general social survey. Dialectics of Nature, 46(12), 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., Ding, H., Deng, M. Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Under the same roof, different behaviors: Non-agricultural employment of couples and household consumption*—A heterogeneity analysis based on a collective decision-making model. Agricultural Technology Economics, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Zhang, T., & Zhang, L. (2024). Research on the influence of digital penetration on the entrepreneurial behavior tendency of rural residents in tourism. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26, 25549–25567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Huang, Y., & Gao, M. (2022). Can digital financial inclusion promote female entrepreneurship? Evidence and mechanisms. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 63, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. H., & Chen, Z. Z. (2024). The impact of clan culture on non-agricultural employment among rural women. Population and Development, 30(02), 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H., & Cui, L. (2019). China’s e-commerce: Empowering rural women? The China Quarterly, 238, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Xia, Y., & Abula, K. (2023). How digital skills affect rural labor employment choices? Evidence from rural China. Sustainability, 15, 6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D., Zha, F., Qiu, W., & Zhang, X. (2024). Does digital literacy reduce the risk of returning to poverty? Evidence from China. Telecommunications Policy, 48(6), 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. L., Qu, C. P., & Wang, S. M. (2024). The income growth effect of digital literacy on farmers. Western Forum, 34(02), 40–54. [Google Scholar]