1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 period, many restrictions were applied to people and businesses. It is a fact that smaller companies have fewer resources to deal with adversity. The entrants in 2017, the focus of this study, are at the beginning of the learning curve. When entrepreneurs decide to open their companies, their behavior is guided by the expectation of profits, proof of their capacity, validation of their ideas and many other motivations. If these expectations are not met, adversities increase and losses persist; closing the business will likely be the most probable outcome.

According to

Porter (

2012), the attractiveness of the sector ends up being decisive in its future. Sectors with small margins require a high level of efficiency. For

Mazzucato and Kattel (

2020), the COVID-19 pandemic represented an enormous challenge for governments around the world, from providing support to citizens and assisting struggling companies to strengthening health services. According to

Paes and de Almeida (

2009), the differentiated taxation of small companies is based on two pillars: equity, reducing disproportionate costs borne by smaller companies, and social objectives of the government, such as poverty alleviation and income distribution. The initial cost constitutes an effective barrier to entry for small businesses, which sometimes opt for informality. Informality is an important source of inequality. In Brazil, there is great difficulty in opening companies, according to the Doing Business report (

World Bank 2020). Compared to 190 economies, Brazil ranks 124th overall. In terms of opening companies, it is in 138th position, and in paying taxes, it is in the worst position, 184th, highlighting the 1501 h per year spent on this task.

Using the World Bank’s concept of the social poverty line,

Bagolin et al. (

2022) highlight that Brazil reached a 30.4% social poverty rate in 2021, which is equivalent to 64 million Brazilians. Regarding informality, there are severe discrepancies between Brazilian regions (

IBGE 2022). According to the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE), based on field research conducted between 2018 and 2021 among closed companies, it was found that there was a higher proportion of people who were unemployed before opening the business who had less previous experience in the field, a higher proportion of those who opened due to customer or supplier requirements and a higher proportion of those who opened out of necessity. Around half of the companies that closed in 2020 considered the pandemic being the decisive factor for their closure (

SEBRAE 2023).

The state of Rio Grande do Sul is in the extreme south of Brazil and is subject to recurring droughts which affect its economy, with agriculture being its main industry. It is the second state in Brazil in generating Gross Value Added (GVA) from agriculture, behind only Paraná. It is responsible for a large part of the country’s production of soybeans, rice, wheat, corn, grapes and tobacco. The state has significant exports of soy and meat, mainly chicken and pork (

Feix et al. 2021). It is also not uncommon for floods to occur in some regions, due to concentrated precipitation and the connection between tributary rivers, the Guaiba River, Lagoa dos Patos, and the sea.

This article analyzes the survival rates of simple regime companies with state registration in Rio Grande do Sul (RS) in the Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS). The objective is to measure the survival of small companies established in 2017, over the period from 2017 to 2023, in order to identify the impact on sectors, such as agriculture, industry, commerce, construction and others, as well as regions and company sizes, with a focus on the closure of small businesses due to its high social repercussions. We also conduct an in-depth analysis of the trade subsectors specifically, as they represent 83% of the number of small businesses. The study aims to clarify where public policies need to focus in times of extreme situations by identifying the sectors, locations and sizes of companies that tend to suffer most. This will result in greater efficiency in the allocation of resources and support measures to mitigate the situation. The data are official from the State Revenue and correspond to information that allows the monitoring of 8931 companies in the Simples Regime of Rio Grande do Sul throughout the study period.

To have a more detailed analysis, we chose to classify these small businesses into three size categories. In this study, we chose to use annual revenue as a criterion instead of the number of jobs. The first includes companies with annual revenues of up to BRL 81,000 equivalent to USD 15,576.92

1, which would be equivalent to an Individual Microentrepreneur (MEI). The second range includes companies with revenues of up to BRL 360,000 (USD 69,230.77), which would be equivalent to a Microenterprise (ME), and in the next and final range, companies with revenues higher than that, but still classified as simple, are defined as a Small Business (EPP). EPPs have revenue limited to BRL 4.8 million annually (USD 923,076.92). In addition to this introduction, this article consists of

Section 2 which presents a review of the literature on small businesses and empirical studies.

Section 3 describes the methodological procedures used in the study.

Section 4 describes the simplified tax regime and the Brazilian government’s support for companies during the COVID-19 pandemic, and presents the results obtained in this research.

Section 5 presents the discussion and the future lines of research. The final section presents the study’s conclusions.

2. Literature Overview

According to

Porter (

2012), competition strategies can be summarized in three factors: cost leadership, differentiation and segmentation or reach. Porter warns that not all sectors of the economy are equally attractive, whether from the point of view of profitability or the factors on which it depends. This is a crucial point for survival analysis. Sectors have different access barriers, whether they be capital, technology, expertise, knowledge, or management. Sometimes, being competitive in a weak industry will do nothing in terms of sustainability. On the other hand, in sectors with high profitability, the company’s position may be sustainable even if it is not very competitive. For

Porter (

2012), there are five forces that determine competence: the entry of new competitors, the threat of substitute products, the negotiating power of customers, the power of suppliers and the rivalry of established companies. Barriers to entry can be enumerated as economies of scale, product differentiation, brand identity, cost variation, capital requirements, access to distribution channels, absolute cost advantage, government policy, and expected retaliation. The government can limit or even prohibit entry into sectors subject to state control through licensing and operating requirements. According to

Porter (

2012), the learning curve is also an important factor, as is access to government subsidies, so the time factor supports those already established in a time of crisis.

The economies of scale occur when the company increases its production level and generates a lower cost per unit. Companies that are unable to grow end up incurring higher unit costs and lower profit margins (

Varian 2010). For

Krugman (

1991), in the search for economies of scale and while at the same time minimizing transportation costs, industrial companies tend to locate themselves in regions of high demand, but the location of demand itself depends on the distribution of production.

For

Porter (

2013), some entrants, when they come from another company that decides to diversify their business, could capture part of the market, influencing prices and costs. This would be the case of a soda company entering the bottled water market. Therefore, not all entrants have the same initial conditions.

Regarding transaction cost theory,

Coase (

1937) describes transaction costs as the costs involved in using the market to carry out exchanges, including the costs of information, bargaining and decision making, and managing contracts. He argues that companies are established and grow by organizing production in a way that reduces these transaction costs. According to the author, the firm will grow as long as its internal transaction costs do not exceed the costs of carrying out the transaction in another firm or in the market.

From the Resource-Based View (RBV) perspective,

di Petta et al. (

2018) carried out a retrospective of Penrose’s work, which argues that companies should be understood as an administrative structure that links and coordinates individuals and productive resources. The objective of the managers is to explore the package of productive resources controlled by the company. In other words, a company’s internal resources are the basis of its competitive advantage. The authors conclude that there is a need for new research on the different ways companies grow and also on other ways of measuring this growth. They emphasize that a broad interpretation of the RBV must be adopted, especially within the context of an increasingly competitive global market.

According to

Teece et al. (

1997), the capabilities approach emphasizes the internal processes that a company uses and their evolution. It indicates that competitive advantage is not just a function of how the process is managed, but also arises from the assets the company possesses, as well as how they can be utilized and redeployed in a changing market.

Eisenhardt and Martin (

2000) conclude that long-term competitive advantage resides in resource configurations and not in dynamic capabilities. In less dynamic markets, RBV is improved by combining the path-dependent leverage strategy with the pioneering change strategy. For the authors, in high-speed markets, the duration of competitive advantage is unpredictable, time is central to strategy, and dynamic capabilities are themselves unstable. Change is the key strategy. An article by

Rashid and Ratten (

2020) studied the dynamic capabilities to understand how small business entrepreneurs are trying to survive and grow in an ecosystem affected by the coronavirus. The results point to the adoption of agile business models and effective business functions.

From the perspective of understanding the life cycle of firms,

Greiner (

1998) and

Churchill and Lewis (

1983) make great contributions. According to

Greiner (

1998), companies go through several stages that present challenges or crises in their growth trajectory. The author develops a model based on five dimensions of this process: the age and size of an organization, its stages of evolution and revolution and the growth rate of its industry. For

Greiner (

1998), the same organizational practices are not maintained throughout the life of the company. As it grows in sales volume or number of employees, the challenges of management, delegation, coordination, communication and collaboration increase, and the environment becomes more complex. Companies that survive a crisis generally enjoy four to eight years of continuous growth without a major economic setback.

For

Churchill and Lewis (

1983), small companies exhibit great variability, encompassing differences in size and capacity for growth, as well as in independence of action, organizational structures and management styles. Categorizing their growth presents a challenge. The authors argue that growth models relying solely on business size and company maturity are inadequate for small businesses, despite their utility in many respects. Their primary critique lies in the assumption within these models that a company must progress through all stages of development or face failure.

To address this, the authors proposed a five-stage model: existence, survival, success, takeoff, and resource maturity. Within the success stage, they identify sub-stages. The Success-Disengagement sub-stage allows the company to remain in it indefinitely as it demonstrates economic health, sufficient size and product market penetration to ensure economic success and earns average or above-average profits. During the Survival Stage, the company may either grow in size and profitability, transitioning into the success stage, or it can remain in the survival phase for an extended period, yielding reasonable returns and eventually closing down when the owner gives up or retires. Family stores are in this category. While some may be sold due to their economic viability, others may fail entirely, ceasing their operations when the owner retires or relinquishes control.

Different perspectives of the traditional staged models will consider a variety of paths or non-linearity in the firm growth.

Dobbs and Hamilton (

2007) analyze the literature on the growth of small businesses since the mid-1990s, covering everything from stochastic models to deterministic management models that continue to dominate the topic. The authors conclude that, despite the growing volume of applied research, there is still no theoretical body capable of explaining the growth of small businesses. Thus, the development of knowledge appears fragmented and not cumulative.

Hamilton (

2012) studies the growth process by analyzing the trajectories of sixty companies during the period from 1994 to 2007. He finds that the size of initial employment has some influence on the nature of the growth trajectory. Furthermore, smaller companies grew more frequently and with more continuity than larger companies, where growth occurred in relatively large, isolated steps, with little continuity. For

Audretsch and Mahmood (

1995), the specific characteristics of the individual establishment influence exposure to risk, and the ownership structure can substantially shape the probability of survival.

For

Agarwal and Audretsch (

2001), the relationship between company size and the probability of survival is shaped by technology and the phase of the industry’s life cycle. Even though the survival probability of small entrants is generally lower than that of their larger competitors, the relationship does not hold in mature phases of the product life cycle, or in technologically intensive products. In technologically intensive sectors, entry can be defined more by filling strategic niches, thus negating the impact of the size of entry on the probability of survival.

Recent studies highlight leadership, adaptation and innovation.

Quansah and Hartz (

2021) studied the strategic and behavioral adaptation of small business leaders, both in their decision-making processes and adaptive practices in periods of general crisis and intense competition. The authors highlight that approximately half of all new businesses fail within the first five years of operation. The results showed that successful leaders avoid organizational complacency and are agile and flexible in determining appropriate management strategies. In addition, they manage their time well, build strong and productive relationship networks and create positive cultures in the workplace.

Katare et al. (

2021) studied the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic shock on small businesses in the United States. According to the authors, the undercapitalized companies were more likely to suffer greater income losses, longer recovery times and be less resilient. Furthermore, the pandemic led to changes in the business model, but not all adaptive strategies led to better business results. A study by

Adam and Alarifi (

2021) associates innovation practices with the performance and survival of small- and medium-sized companies. The results showed that the innovation practices adopted by companies to face the repercussions of COVID-19 had a positive impact on business performance and probability of survival. They also indicated that external support strengthened the positive impact of innovation practices on the survival of companies, but not on their performance.

Recently,

Mazzucato (

2018) criticized business actions that only extract value through pricing policies or barriers to entry, exploiting some specific advantage, instead of creating value through the production of something new. The author classifies this as rent-seeking. In this sense,

Mazzucato (

2021) argues that the State needs to play a leading role in the development of markets that generate value.

In a study conducted by

SEBRAE (

2023) which was based on data from the Federal Revenue Service and field research carried out between 2018 and 2021, of the companies that were closed during 2020, Individual Microentrepreneurs (MEIs) have the highest failure rate among Small Businesses and 29% close after 5 years of activity. Microenterprises (Month) have an intermediate failure rate among Small Businesses, as 21.6% close after 5 years of activity. Small Businesses (EPPs) have the lowest failure rate among Small Businesses, with 17% closing after 5 years of activity. The highest failure rate is seen in commerce (30.2% close in 5 years) and the lowest in the extractive industry (14.3% close in 5 years). Our study presents similar results and confirms that companies with lower revenues are those with higher failure rates and, therefore, require greater support.

Empirical Case Studies

Several studies rely on employment data to classify company size using data from the Annual Social Information List (RAIS). A study by

Conceição et al. (

2018) analyzed the effects of

Simples Nacional on the longevity of industrial microenterprises in RS, based on RAIS microdata from the period 2007 to 2013. It identified that companies created in 2007 and opting for

Simples Nacional had a 30% lower chance of failure than non-opting companies. The sample included 3187 industrial establishments.

Rodas Céspedes et al. (

2020), in a study on the survival of companies in RS for the period 2007–2013, based on data from RAIS, uses the Kaplan–Meier procedure to obtain the survival functions of companies, depending on location, economic activity, and size. The Cox procedure was also used to determine the effect of company size. The results showed that survival is relatively higher in companies with a greater number of employed people. In this study, smaller companies (1 to 4 people employed) had the lowest survival rate, equivalent to 34% in year 7. It also detected the greater survival in companies located in the Northeast region of Rio Grande do Sul, using the concept of mesoregion.

According to

IBGE (

2023) in an analysis of company survival from 2017 to 2021, for companies created in 2016, the overall survival rate was 78.0% after one year of operation (2017) and it fell to 43.0% after five years (2021). They found a direct relationship between size and survival; that is, the larger the size of the entity, the higher the survival rate. For companies without employed personnel in the fifth year, the survival rate was 38.0%, followed by 53.8% for companies with 1 to 9 employees, and 69.4% for companies with 10 or more employees. A study by

Resende et al. (

2016) highlights the positive role played by company size in survival and the negative influence exerted by the minimum efficiency scale and the suboptimal scale. They also highlight regional inequalities as responsible for important variation in survival rates.

Fotopoulos and Louri (

2000) conducted a study on companies in Greece from 1980 to 1992, seeking to evaluate the role that location plays in the company’s survival. The results indicated that location in Greater Athens, compared to the rest of the country, positively affected survival, especially when it comes to smaller companies. This study is one of the few counterintuitive analyses.

Wennberg and Lindqvist (

2010) investigated the effects of five clusters on the survival and performance of new entrepreneurial firms in Sweden. They found evidence that a high concentration of employment in the cluster itself was related to better chances of survival; however, the results are weaker and inconsistent for measures of relative agglomeration such as location quotients.

Phillips and Kirchhoff (

1989), analyzing small companies in the United States, concluded that survival rates vary according to the sector, with the manufacturing industry being the highest (46.9%). According to the authors, two in five new small businesses survive at least six years and more than half of the survivors grow. Companies that grow double in their survival rate, and particularly if growth occurs earlier in the company’s life, have a greater probability of survival. On the international scene,

Mata and Portugal (

1994), analyzing Portuguese industrial companies, found that a fifth of them failed during the first year of life and only 50% survived four years.

Leurcharusmee et al. (

2022), when analyzing the survival of micro and small businesses in Thailand, using survey data from three rounds, assessed the impact of COVID-19 on the probability of survival in the tourism and manufacturing sectors. The Cox proportional hazards model and the Kaplan–Meier estimator were employed. The findings showed a gradual decrease in the probability of survival from the first week of interview and approximately 50% of small businesses were unable to survive more than 52 weeks during the COVID-19 pandemic. They also observed that the survival of companies primarily hinges on factors such as location, the number of employees and the adaptation of the business model to operate within the context of social distancing and online marketing. They particularly emphasize that retaining workers and avoiding reductions in working hours are among the main factors that enhance survival capacity.

An OECD study (

OECD 2015) analyzes the influence of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs/SMEs) in associated countries and members of the G20. It emphasizes that SMEs face challenges in accessing financing, and the tax system plays a dual role, sometimes supporting and sometimes hindering. Furthermore, it highlights that there is a tendency for debt to be the detriment of social capital and, not in the least, high compliance costs. In general, governments provide tax preferences and simplification measures aimed at SMEs to alleviate these conditions. According to the

OECD (

2015), younger companies tend to have a higher failure rate than older companies, with more than half of companies failing within the fifth year of operation. In 2012 data, the survival rates of selected countries in the fifth year were as follows: Hungary 27%, Spain 29%, Italy 38%, Portugal 39%, Slovenia and the Czech Republic 43%, Luxembourg 50% and Austria 55%.

3. Methods and Data

The objective of this study is to analyze the survival of 8931 business operating under the simplified taxation regime, established in 2017, in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, from 2017 to 2023. This period encompasses the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an extreme event that induced economic impacts worldwide. Moreover, Rio Grande do Sul frequently encounters extreme weather events including drought and flood. Identifying the businesses most affected by such extreme events, whether categorized by activity, location, or size, can facilitate the design of more effective public policies.

Survival analysis is one of the most applied statistical techniques today, especially the Kaplan–Meier estimator (

Kaplan and Meier 1958) and the COX model (

Cox 1972). The response variable for this type of analysis is the time elapsed until the occurrence of an event of interest, which is called the failure time, which in this case is the closure of the company. According to

Colosimo and Giolo (

2021), the objective of survival analysis is to determine the probability of survival and the risk of failure or closure of a group of companies, with the determinants being time itself and variables called covariates. According to

Carvalho et al. (

2011), survival analysis allows problems to be dealt with in which the occurrence of the event is not constant over time.

The main characteristic of the database is the presence of censorship; in this case, it is the companies that survived. Without the presence of censored data, statistical techniques such as regression could be applied. The Kaplan–Meier method may be limited when there is a small sample, or when there is competitive censorship or when looking at the long term. The method also does not use covariates, which is why the COX procedure is additionally applied. For

Govindarajulu and D’Agostino (

2020), the assumption that censorship must be independent of the real time of the event has been significantly underestimated in survival analyses. The author highlights the evolution that the Cox model brought with semiparametric analysis, allowing to combine the advantages of both models, nonparametric and parametric.

In this study, our interest is to determine to what extent small businesses in Rio Grande do Sul had their survival affected during the last seven years, when they were at certain times limited by the restrictions imposed during COVID-19. The data used in this study are from the State Revenue of RS, covering the period from 2017 to 2023. The companies created in 2017 and registered in the national Simples system, with declared revenues, are those that make up this study. The revenue reported to the State is used to define the size of the company, which is a differentiating factor of this work.

The variables used in this model are described in

Table 1. In the first analysis, there are a total of 8931 companies. A second analysis, restricted to the commerce sector, was carried out on 7455 companies with the same variables, where only the subsectors were differentiated.

There are three size ranges. The first range comprises companies with an annual revenue of up to USD 15,576, which would be equivalent to a Individual Microentrepreneur (MEI). The second range encompasses companies with revenue of up to USD 69,230, which would be equivalent to a Microenterprise (ME); in the next and final range, companies with revenues exceeding this would be classified as Small Businesses (EPP).

The second form of analysis is geographic location. The state of Rio Grande do Sul is divided into nine functional regions (

Estado do Rio Grande do Sul 2011). Furthermore, we analyzed using activities second to the National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE), which are condensed into six sectors (Agriculture, Industry, Construction, Commerce/Business, Financial, and the last Education and Health, and others).

Table 2 shows the distribution of the companies established in 2017, along with size, region and economic activity. They represent all companies that are registered with tax authorities and report their revenues. Companies which do not report any activity were not considered.

The study also uses Cox’s semiparametric technique, with the purpose of testing the effect of size, sector of activity and region. The survival function is defined as the probability of an observation not failing until a certain time t, that is, the probability of an observation surviving time t. This is written as:

T is the non-negative random variable. The cumulative distribution function is defined as the probability of an observation not surviving time t, i.e.,

The survival function is equal to 1 at the beginning of the period, and as time passes it tends to decrease or remain constant. The failure rate function λ(t) is useful for describing the lifetime distribution of companies, as it describes the way in which the instantaneous failure rate changes over time.

The increase in the function indicates that the company’s failure rate increases over time. In total, this study analyzed 8931 companies, with an event occurring in 3159 (35.4%) and 5772 being censored (64.6%). As an example, if the number of companies corresponding to year 1 is 82, and that to year 2 is 549, the estimate should decrease due to the failures that occur during these times. In year 1, there are 8931 companies at risk before t = 1 and 82 fail. Thus, the estimate of the conditional probability of failure in this range is 82/8.932 and the probability of surviving is 1 − 82/8.932 = 99.08%. In the second year, it would be 1 − (82 + 549)/8932 = 92.93%. This can be written as follows:

Survival analysis refers to the probability of a company surviving after a certain time; if formulated via risk analysis, it refers to the risk of a company closing after having survived a certain period (

Carvalho et al. 2011). The risk function can be obtained from the survival function. Therefore:

The estimation is carried out using the maximum likelihood method. For Kaplan–Meier, the probability of survival at moment t

j is estimated by the number of survivors at that moment, [R(t

j) − ΔN(t

j)], divided by the number of establishments at risk up to that moment R(t

j). Therefore:

The function can be represented according to strata originating from the classification of covariates and is thus able to evaluate the survival of subgroups, which may present important variations. The Log-rank hypothesis test is used to evaluate these subgroups. The null hypothesis is that the risk is the same for each extract. To estimate the effects of covariates, COX modeling is used. This model adopts proportional risks; that is, the risk of closing a company does not vary over time in relation to another company. This can be tested using a graphical approach or via the Shoenfeld Residuals Test (

Schoenfeld 1982).

4. Results

To support small businesses, Brazil adopted a simplified taxation regime called Simples Nacional. It is a shared tax collection and inspection regime created by Complementary Law 123/2006 and covers Micro and Small Businesses (EPPs). Companies, after formalizing their business at the Commercial Board or at the Notary’s Office, must opt for the Simples Nacional tax regime.

The regime is administered by a Management Committee shared between the federated entities (Union, States, Federal District and Municipalities). Simples, as it is called, unifies the calculation and payment of the following taxes: Corporate Income Tax (IRPJ), Contribution on Net Profit, Tax of Industrialized Products, Employer Social Security Contribution, the state ICMS and municipal Service Tax (ISSQN), and some other federal contributions. The basis for calculating and collecting the tax is the company’s revenue, and the rates have percentages scaled according to revenue. The lowest rate is 6% and it can reach 33%.

The State of Rio Grande do Sul (RS) also has its own simplified regime that expands the benefits of the national

Simples. The “

Simples Gaúcho” was established by Law No. 13,036 on 19 September 2008, and grants additional benefits to companies registered in national

Simples (

Estado do Rio Grande do Sul 2021). In 2021, in the context of a state tax reform that aimed for, in addition to fiscal sustainability, the economic efficiency of tax incentives, “

Simples Gaúcho” was redesigned, maintaining the ICMS exemption range at 0% for companies with an annual revenue of up to USD 69,230 (BRL 360,000), and extinguishing the eight subsequent bands that implied a scale of ICMS percentage discounts that varied from 40% to 3% for companies with revenues between USD 69,230 (BRL 360,000) and USD 692,307 (BRL 3,600,000).

4.1. The Government Support during COVID-19

The impact of COVID-19 on the Brazilian economy occurred within a unique context. The Brazilian economy was just recovering from a crisis entirely unique in 2015 and 2016, which persisted into 2017. It consisted of a political crisis, a crisis of governability that culminated in the impeachment of the President of Brazil and which had among its alleged reasons the disrespect of fiscal rules, and also of the economic crisis that the country had already been suffering and which was getting worse.

While world GDP followed a path of growth, Brazil was out of step. In 2018, the economy began to recover, and in 2020 it faced the pandemic and its consequences. Unemployment was already at a high level, above 9%, having reached 13.90 in March 2017; this gradually decreased only to rise again, reaching almost 15% during the COVID-19 period (

Figure 1).

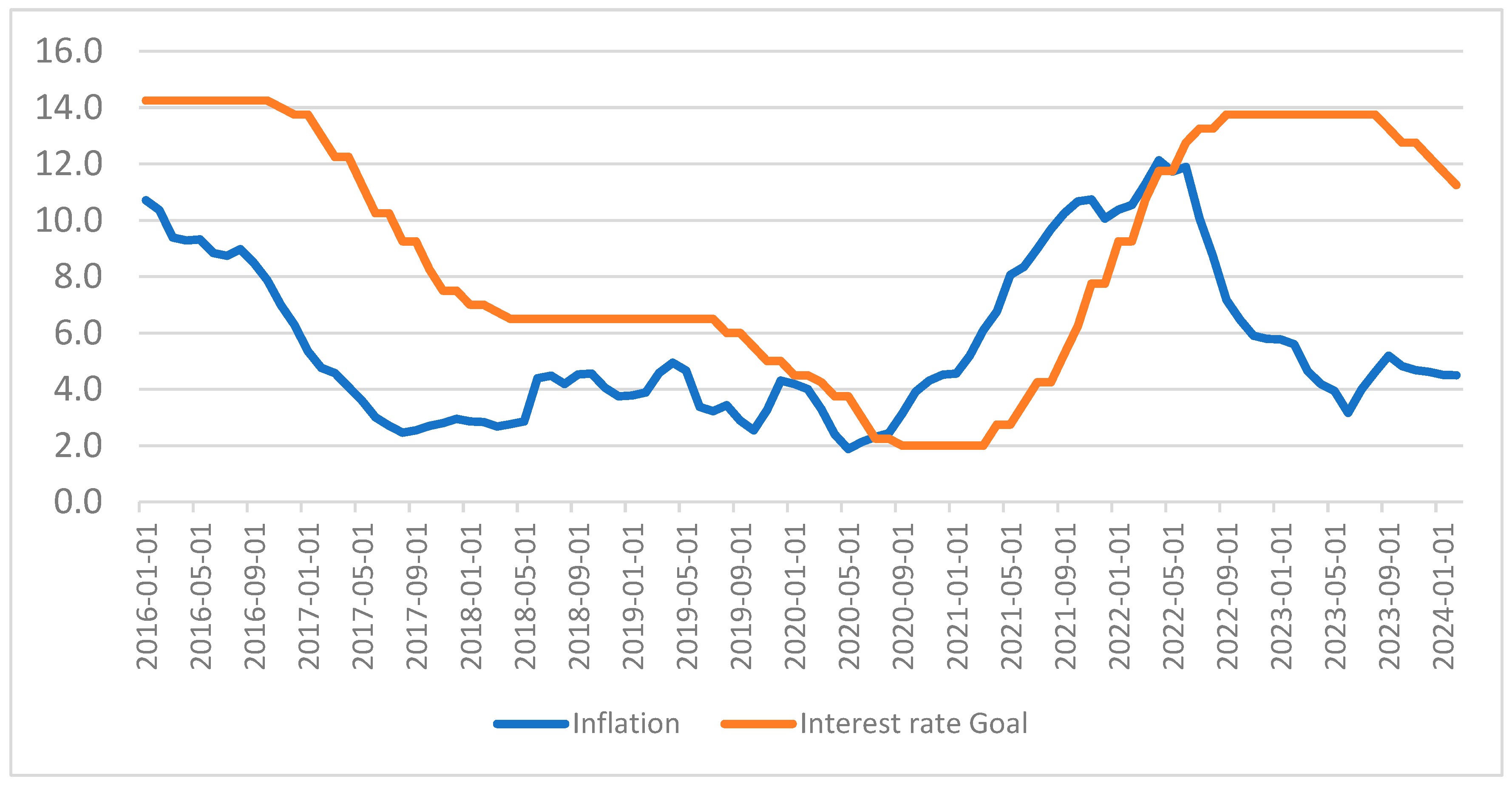

Inflation also played a crucial role in this scenario before and during COVID-19 (

Figure 2). It went through a period of strong deceleration, even falling below the target of the Central Bank of Brazil, which had been around 4%; this led to the promotion of a monetary policy of a certain degree of relaxation never before seen in the country. Nominal interest rates, which were already at 4%, were reduced to 2% per year. With the onset of logistical supply instability, inflation returned very strongly to the national scenario, prompting a very sharp increase in the interest rate with the aim of containing it; this was perhaps the greatest acceleration among all countries.

Many measures were taken at country and federal state level. Budgetary resources were used as well as a strong performance by public commercial and development banks to mitigate the economic slowdown.

Table 3 presents some of the measures adopted.

Regarding labor issues, the possibility of reducing working hours and also suspending employment contracts was provided for companies with an annual revenue of up to BRL 4.8 million. The Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) adopted a series of measures to release capital and liquidity to banks so that the financial system could provide appropriate responses to the situation (

BCB 2020).

Mazzucato and Kattel (

2020) argue that governments, to manage a pandemic, need dynamic capabilities that are often absent, such as the ability to adapt and learn, to align public services with citizens’ needs, and to govern data and digital platforms. In the RS state, projects in the fiscal area sought to contribute to the situation they were facing, such as the Devolve-ICMS (tax refund for low-income people) project, which reduces the regressivity of the consumption tax for people with the lowest income (

Tonetto et al. 2023a), and the Menor Preço Brazil application, which made it possible to find better prices and reduced travel and the risk of contagion, customized to search for products to combat COVID-19 (

Tonetto et al. 2023b). The Receita Certa project was also an attempt to improve citizen engagement (

Tonetto et al. 2024). RS’s tax administration has improved in recent years, and was notable for supporting companies’ tax compliance, and placing less emphasis on the punitive aspect.

SEBRAE/FGV (

2022), in a continuous survey repeated for 14 months with more than 13,000 responses, analyzed the impact of the pandemic on small businesses and shows that the recovery is relatively satisfactory. It points to a reduction in the proportion of companies reporting a reduction in their revenue. The research reveals that these companies obtained most of their loans in 2020 and 2021. However, it points to a reduction in expectations for the situation to return to normal and an increase in the proportion of entrepreneurs concerned about the future of their company. It reveals that some segments most affected, such as beauty, tourism, and fashion, still have revenues 30% or more lower than previously. And less affected sectors such as agriculture, industry and business services still show a 10% reduction compared to the previous situation. Regardless of the range (MEI, ME, EPP), everyone reports that the increase in costs is their main concern (50%), followed by the lack of customers (>20%).

According to

da Silva and Saccaro (

2019), in an analysis of the effects of credit from the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) on the survival of Brazilian companies created before 2002, for the period from 2002 to 2016, companies that used the BNDES Finame credit line had longer survival times than those that were not included. Furthermore, it was found that the smaller the company, the greater the effect of this financing on its survival. However, it had no effect on the survival of large companies.

Zhou et al. (

2023) analyzed the impact of government economic interventions to improve the survival of small-, micro- and medium-sized enterprises in the COVID-19 pandemic. The study concluded that tax relief was the most important intervention used to support firms during the pandemic. Cash grants and cheap credit were also used during the period but had little impact.

4.2. The Study Findings

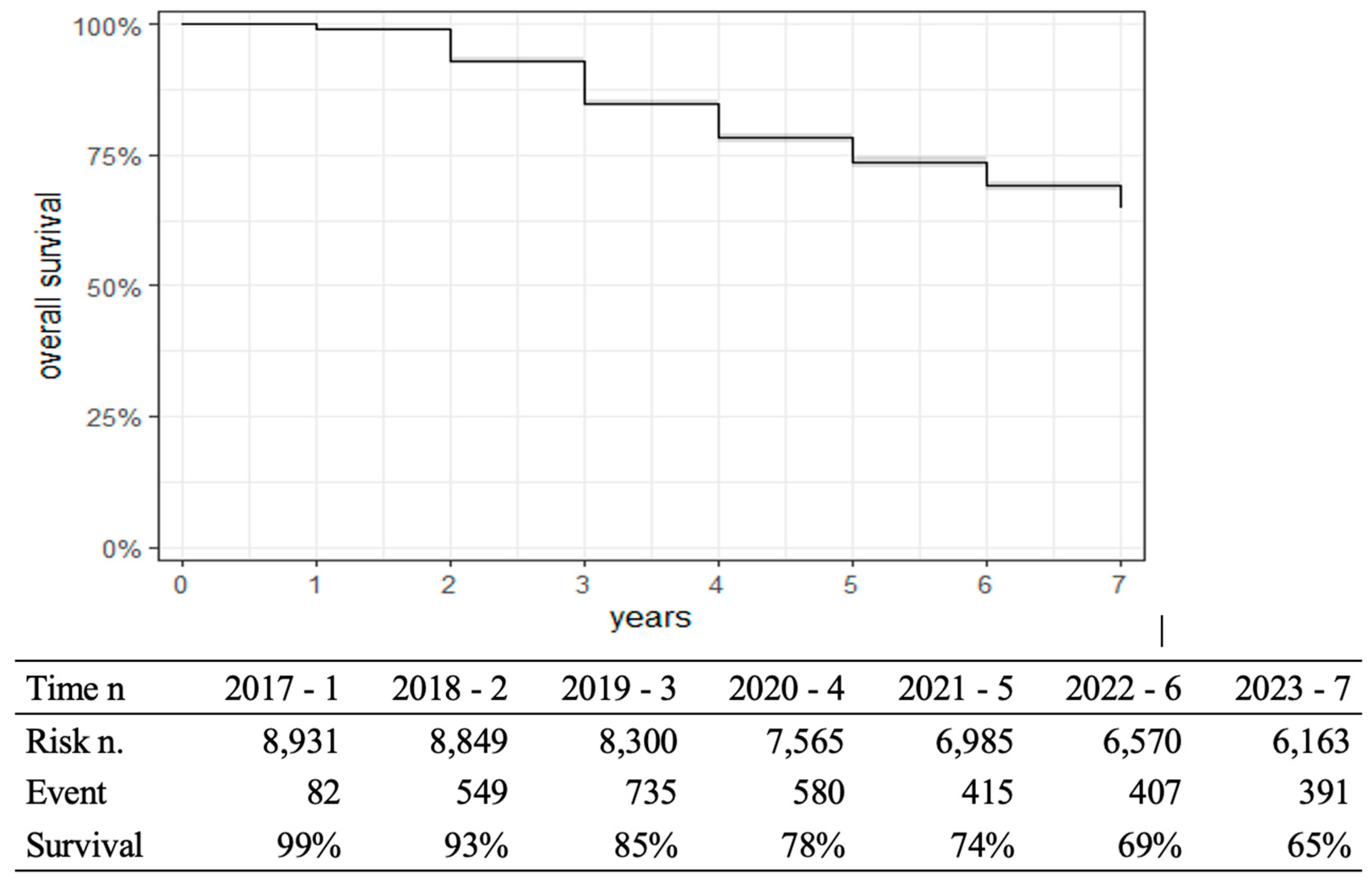

The global analysis represented in

Figure 3 shows the survival percentage year by year since 2017. The largest number of events occurred in 2019, followed by 2020, the first year of COVID-19. Later it was observed that the number of events remains stable.

The potential reasons for the excess of events in 2019 may be attributed to the challenges of company growth as advocated by

Greiner (

1998). Additionally, macroeconomic factors could have played a role, such as high unemployment. Another contributing factor could have been the limited access to credit, a situation that was only partially addressed from 2020 onwards, as reported by

SEBRAE/FGV (

2022).

In relation to the size of the companies, as shown in

Figure 4, the largest companies, with yearly revenues above USD 69,230 (BRL 360,000), have the highest survival rate (78%). And the smallest companies, with revenues of less than USD 15,576 (BRL 81,000), are the most affected, with only 39% surviving to year 7. Analyzing the first quartile of companies that close down their activities, it is observed that this occurs in the third year for Size 1, and in the fifth year for Size 2 companies, showing a greater resilience of the latter.

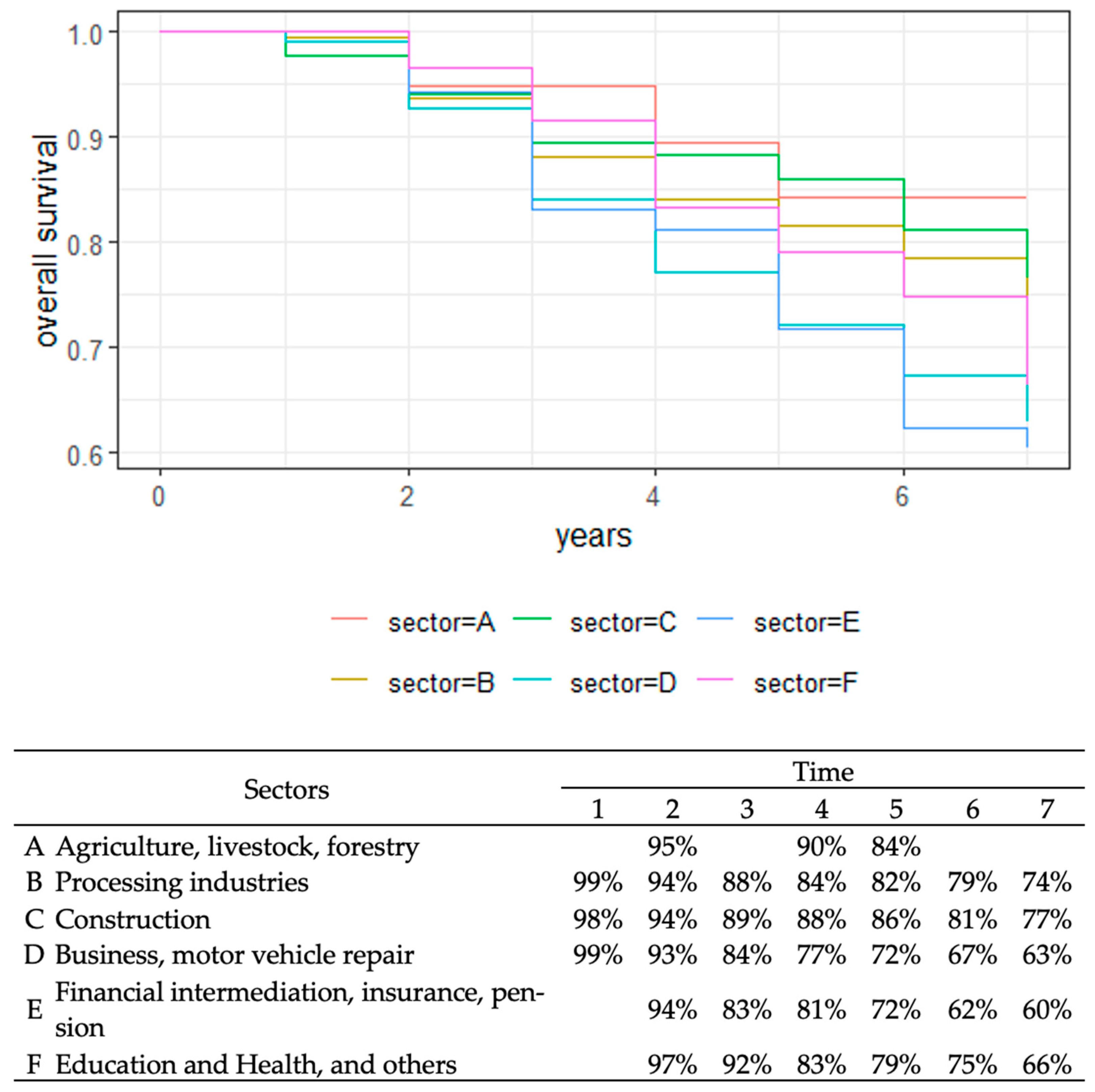

The analysis by sectors of economic activity shows trade (63%) and financial intermediation and insurance as the most affected (60%); this process deepened in 2019 and spread in the following years (

Figure 5). Financial intermediation and insurance showed a greater drop than commerce in 2021, probably due to the consequences of claims. The third most affected sector in its survival was education and health (66%). It is worth noting that 87% of events occur in the commerce sector and 9.7% in industry.

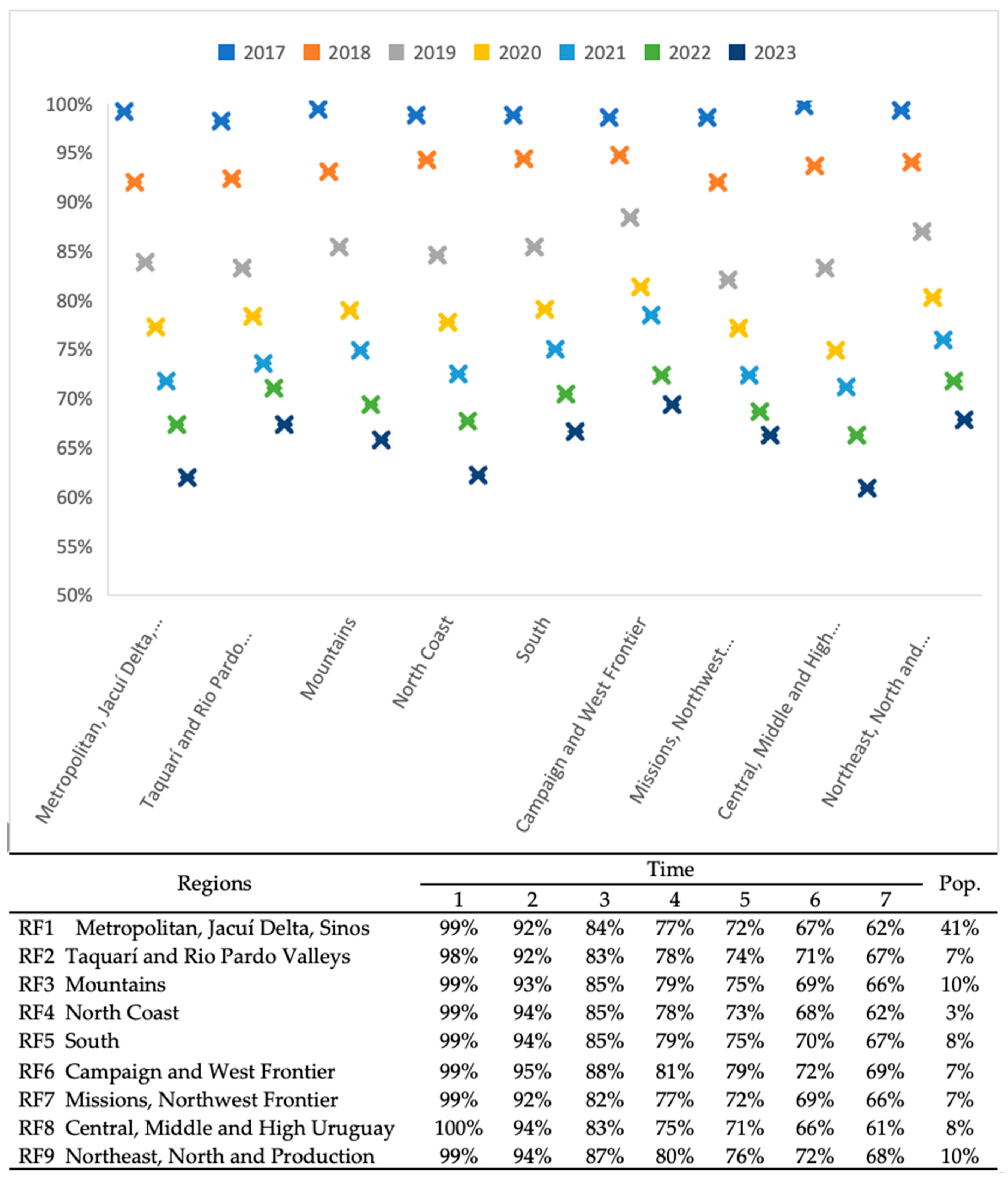

Figure 6 is based on the functional regions of the State (

Estado do Rio Grande do Sul 2011). The regions of Campaign and West Frontier, and also North, Northeast and Production stand out with higher survival rates in the seventh year, at 69% and 68%, respectively.

This may be attributed to the highest survival rate in these regions due to their production of primary products, sectors that were comparatively less affected by the pandemic. The Central (61%), Metropolitan (62%) and North Coast (62%) regions have the highest percentage of activity closures. It is interesting to note that the percentage of small business closure events is very similar to the region’s representation in the state’s population. This trend is surpassed more clearly only in the Mountains and on the North Coast. A study by

IBGE (

2023) reveals that company exit rates in the five Brazilian regions generally decreased from 2019 to 2021, with 2019 being the year with the highest number of exits in all regions. It considers homogeneous survival rates, with the South region having the highest probability of survival.

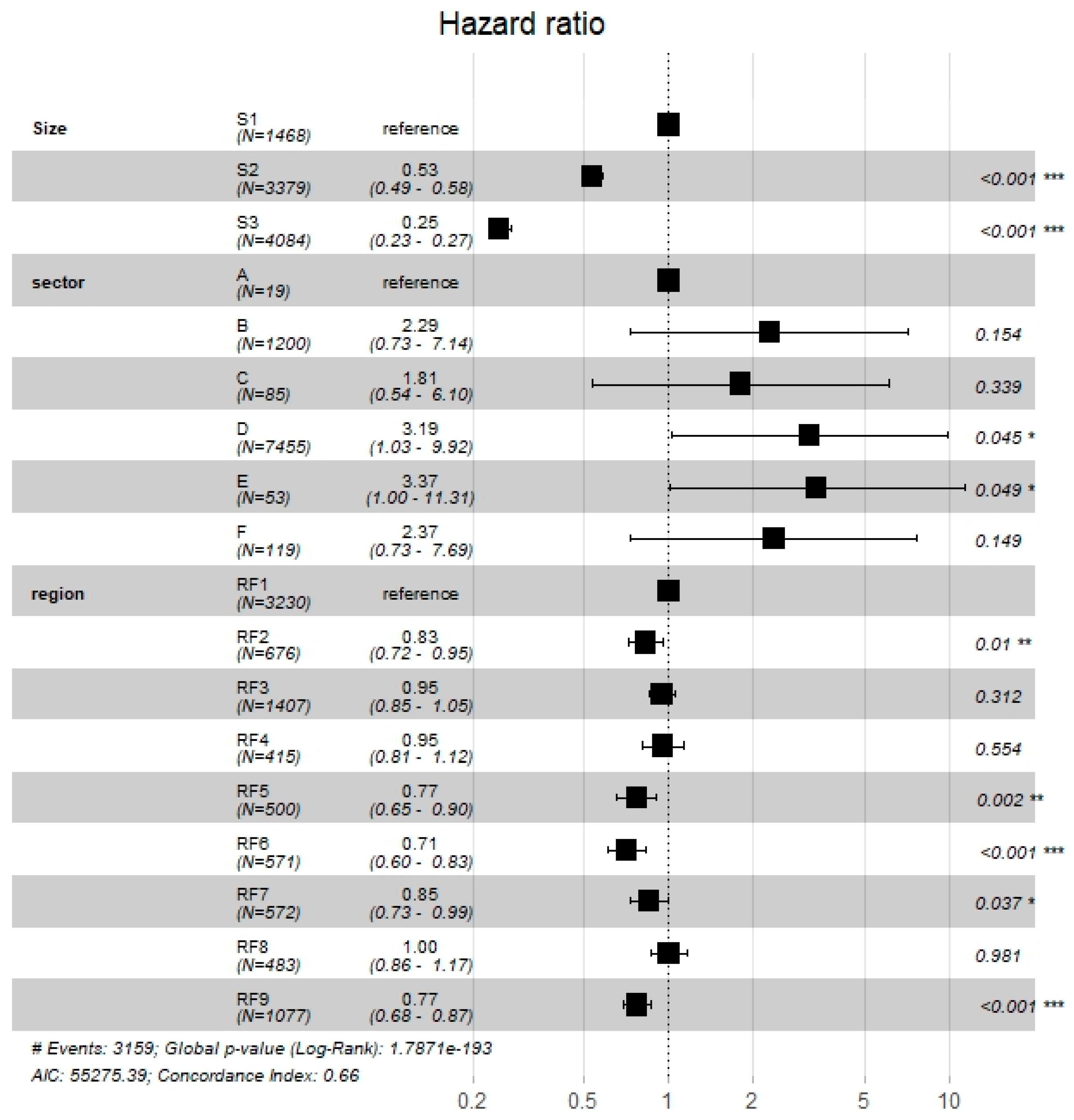

Unlike the Kaplan–Meier procedure, in which the time variable determines the survival and/or risk of failure of establishments, in the Cox model the risk of closure is the result of the effect of one or more explanatory variables, in this case the size of the small companies, their regional location and their economic activity. The choice of these three variables is based on the literature and similar empirical studies, and is dependent on the availability of information.

Figure 7 initially highlights sizes in relation to MEI, which is the smallest company size (S1). Microenterprises (S2) have 47% less chance of the event occurring, and EPPs that are larger (S3) have 75% less chance of the closure event occurring. Both are significant. This indicates a positive linear relationship between size and survival.

When comparing sectors, agriculture is the reference because it is the great economic strength of the state. The sectors of commerce (business) and financial intermediation and insurance stand out, with an increase of more than 200% in the number of events. In relation to regions, the metropolitan region serves as a reference as it represents 41% of the state’s population, including the capital Porto Alegre. According with

Figure 7, the most significant reductions in the percentage of events are found in regions 6 and 9, Campaign and West Frontier (−29%) and North, Northeast and Production (−23%), respectively.

Table 4 presents the risk proportionality test, where the null hypothesis assumes that the risks among establishments are proportional as time progresses. The sector and region variables present values that confirm the validity of the analysis. However, the size variable indicates the potential for stratification to be applied.

The second analysis is carried out exclusively on Commerce with a sample of 7455 companies and presents results similar to the previous one in terms of size and location.

The difference in results appears in the commerce subsectors, where transport has a survival rate that worsens by 60% compared to the automobile sector, which is the reference. This then followed by wholesale with a worsening of 168%, followed by the retail sector with 194%. The accommodation and food sector have a worsening of 209% (

Figure 8). It is worth noting that 2019 was a year of an average drop of 10% in the survival rate in the wholesale, retail and accommodation and food subsectors, and in 2020, the falls in retail (9%) and in accommodation and food (11%) remained high, returning to the average annual drop of 7% seen before in 2018 and after in 2021 onwards, in terms of these three most affected activities. The fuel, automobile and telecommunications sectors suffered less than the others.

5. Discussion and Future Lines of Research

The objective of this study was to analyze the survival rate of small businesses from 2017 to 2023, in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. This period is particularly important because during 2020 and 2021, many restrictions were adopted to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and companies had to adapt to these contingencies. Also, many actions were taken by the government. In order to carry out this analysis, we used the Kaplan–Meier procedure for survival analysis, complemented with the Cox procedure, to determine the effects of company sizes, sectors of economic activity and the regions where they operate on survival time. As the commerce sector is the one with the highest number of companies opening, a second analysis was carried out only with this sector using the same criteria, but only considering its most representative activities.

The results corroborate the relationship between size and survival, which can be inferred from the RBV literature which states the greater the resources, the greater the chance of survival. Empirical studies also highlight this relationship.

In the case of a major crisis such as this, sector-specific scenarios emerge. Some sectors or companies may experience less impact due to lower exposure, such as the fuel or communications sector, and may even find opportunities for growth. Despite increased travel restrictions, individual transport was favored over collective transport. Addressing employment protection measures, as adopted in Brazil, is supported by the study conducted by

Leurcharusmee et al. (

2022). Additionally, easier access to finance also appears to have had a significant effect. The

OECD (

2015) highlights the challenges small businesses face in accessing finance. The poorer outcomes observed in the metropolitan region, characterized by higher population and enterprise density, as well as increased competition, underscore the need for immediate assistance.

We highlight that the results found must be credited to multiple factors, with the COVID-19 pandemic as the main negative factor, added to the challenges that arise for the growth of small businesses highlighted in the literature (

Greiner 1998;

Churchill and Lewis 1983), the scarcity of resources (RBV theory), and credit restrictions in the previous period (

SEBRAE/FGV 2022). The counterpoint was government actions that provided a flood of credit to companies, aid to people, and tax relief, among others. The study of

Zhou et al. (

2023) emphasizes the importance of the tax relief. Some recent studies highlight the relevance of leadership, adaptation and innovation in times of crisis (

Quansah and Hartz 2021;

Katare et al. 2021;

Adam and Alarifi 2021).

Future Lines

A limitation of this study is the same one pointed out by the

OECD (

2015), which reports that there are many alternative definitions for the concept of small business among OECD and G20 countries. The simplified tax regime itself that serves as the area covered by this study is not the same among all Brazilian states. In RS, there is an extended simplified regime.

Another limitation is that it is restricted to just one Brazilian state, although it has a population size comparable to countries such as the Dominican Republic, Greece, Portugal, or Sweden, and a Gross Domestic Product similar to Angola or Ecuador. The methods used non-parametric and semi-parametric analysis that do not allow for more extensive conclusions.

We strongly recommend a continued analysis in the following years, especially after the implementation of the new Brazilian tax reform approved in 2023. Other lines of study may involve companies that exceed the simplified taxation limit, to verify that leaving the regime does not have a negative effect on the survival of companies. It is still possible to repeat this analysis model in the recent future, due to the damage that has occurred recently in May 2024, in the biggest climate catastrophe in the history of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, where cities remained flooded for a month, including part of the state capital and many cities in the metropolitan region.

Other lines of research can be dedicated to the zero-carbon economy in small companies and, not in the least, employee satisfaction. The ESG agenda must be gradually added to the practice and literature of small companies.

6. Conclusions

The results show the great significance for size, with microenterprises having a 47% improvement in survival rate and small-sized companies (EPP) an improvement of 75%, compared to those companies with revenues of up to USD 15,576 per year (MEI), the smallest. As for sectors, the study presented commerce and financial companies as significant, both with a worsening in the survival rate of more than 200% compared to the reference sector agriculture. The regions, when compared to the metropolitan region, generally presented a better survival rate; however, with great significance, these were only region 6, Campaign and West Frontier (−29%), and 9, Northeast, North and Production (−23%), followed by region 5, South (−23%) and 2, Taquari and Rio Pardo Valleys (−17%), and region 7, Missions, Northwest Frontier (−15%). Region 8, Central, Middle and High Uruguay, has a position identical to the metropolitan region, but is not significant.

The analysis restricted to Commerce highlights that the transport subsector presents a worsening of 60%, always in relation to the automobile sector, which is the reference, then the wholesale sector with a worsening of 168%, followed by the retail sector with 194% and the accommodation and food sector with 209%.

In general, government aid during the COVID-19 years appears to have been effective. Sectors that suffered most were commerce and financial companies, and within Commerce, retail and food and accommodation. Several sectors have shown great resilience. Size is highlighted as the most important factor. Commerce, as the sector with the highest entry, is naturally the most subject to the closure event, as in many cases it does not require as much capital or as much expertise. We can also infer that the review of Simples Gaúcho that took place in 2021 is adequate, as it maintains the benefit only for companies that in this study presented the lowest survival rate according to revenue size, (Size 1—39%, Size 2—60%).

The economic literature also tends to validate the results found, as the many barriers for entry, to grow and survive remain, especially in the Brazilian context (

Agarwal and Audretsch 2001;

Porter 2012;

OECD 2015;

World Bank 2020;

Rodas Céspedes et al. 2020). Our study presents similar results as

SEBRAE (

2023) and confirms that companies with lower revenues are those with higher closure rates and, therefore, require greater support. This also confirms that the highest closure rates were in commerce.

The results can be a proxy for public policies that are more targeted at the most vulnerable companies, depending on their economic activity and size, and can be extrapolated even at a global level. The results by region serve to make regional policies more efficient. They also contribute to deepening knowledge of the life cycle of small businesses and their disadvantages in times of catastrophes.

In any case, the database used in this study is robust, providing reliability for its results. This study can serve as a guide for public policies that aim to mitigate the vulnerabilities explained here.