Impacts of Regional Integration and Market Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Balances of Selected East African Countries: Potential Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area

Abstract

1. Background

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Model

3.1.1. Theoretical Framework

3.1.2. Empirical Model

3.2. Data and Sources

3.3. Model Estimation and Results

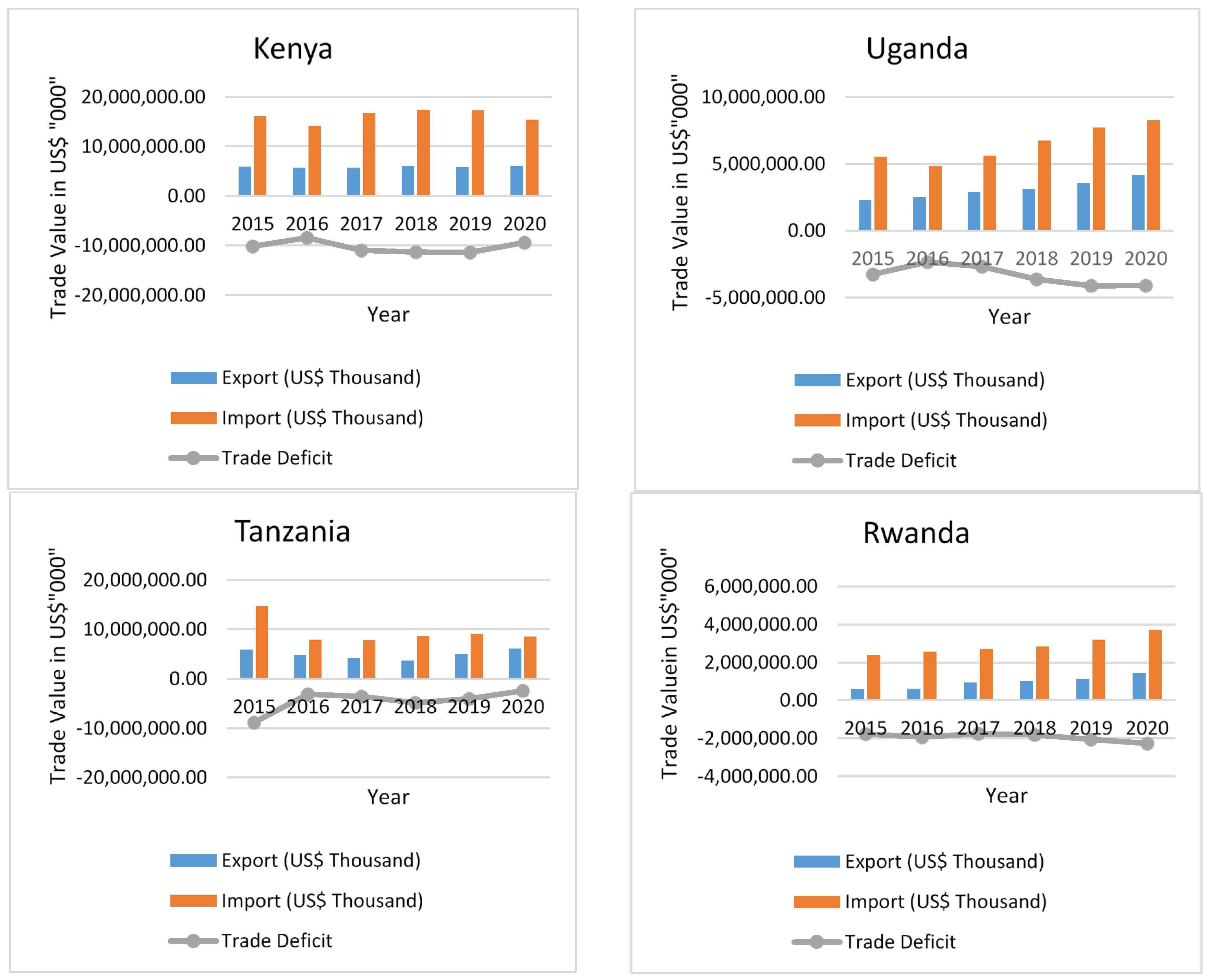

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.3.2. Unit Root Tests

3.4. Panel Regression Results for Bilateral Trade Balances

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Tariffs on Trade Balances

4.2. Impact of Active Participation in FTAs on Bilateral Trade Balances

4.3. Effect of Distance on Bilateral Trade Balance

4.4. Effects of Relative Income on Trade Balances

4.5. Effect of Exchange Rate on Bilateral Trade Balances

4.6. Effect of Relative Price on Bilateral Trade Balances

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Appendix A

TARGETED RESPONDENTS

|

| Issues to obtain stakeholder views on |

General views on the potential impacts of AfCFTA for countries in national trade balances.

|

TARGETED PARTICIPANTS

|

| Issues to seek perspectives of traders on |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 | Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo—DRC. |

| 2 | Rwanda, Burundi, and the DRC. |

| 3 | United Republic of Tanzania. |

| 4 | Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and the Federal Republic of Somalia. |

References

- Abrego, Lisandro, Mario de Zamaróczy, Tunc Gursoy, Salifou Issoufou, Garth P. Nicholls, Hector Perez-Saiz, and Jose-Nicolas Rosas. 2020. African Continental Free Trade Area Potential Economic Impact and Challenges. SDN/20/04. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Adeboje, Oluwafemi Mathew, Abiodun Folawewo, and Adeniyi Jimmy Adedokun. 2022. Trade Integration, Growth and Employment in West Africa: Implications for African Continental Free Trade Area (Afcfta). Preprint, in review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afesorgbor, Sylvanus Kwaku. 2017. Revisiting the effect of regional integration on African trade: Evidence from meta-analysis and gravity model. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 26: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afesorgbor, Sylvanus Kwaku. 2019. Regional Integration, Bilateral Diplomacy and African Trade: Evidence from the Gravity Model. African Development Review 31: 92–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union. 2018. Agreement Establishing The African Continental Free Trade Area. Available online: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36437-treaty-consolidated_text_on_cfta_-_en.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2003. Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle. American Economic Review 93: 170–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, Dennis R., Alfred J. Field, and Steven L. Cobb. 2010. International Economics, 7th ed. The McGraw-Hill Series Economics. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, Imtiaz, Lubna Khan, Fatima Farooq, and Tahir Suleman. 2020. Impact of International Trade and Trade Duties on Current Account Balance of the Balance of Payment: A Study of N-11 Countries. Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies 6: 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, Mohsen, and Taggert J. Brooks. 1999. Bilateral J-Curve between U.S. and her Trading Partners. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 135: 156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenton, Paul, Alberto Portugal-Perez, and Julie Régolo. 2014. Food Prices, Road Infrastructure, and Market Integration in Central and Eastern Africa. Policy Research Working Papers 7003. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, Mehmet. 2016. Currency Depreciation, Trade Balance and Intra-Industry Trade Interactions in Turkey’s OECD Trade. International Journal of Economics and Finance 8: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- East African Community. 2015. Agreement Establishing a Tripartite Free Trade Area among the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the East African Community and the Southern African Development Community. Available online: https://www.eac.int/documents/category/comesa-eac-sadc-tripartite (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- East African Community. 2024. Overview of EAC. Available online: https://www.eac.int/overview-of-eac#:~:text=The%20East%20African%20Community%20(EAC,of%20Uganda%2C%20and%20the%20United (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Echandi, Roberto, Maryla Maliszewska, and Victor Steenbergen. 2022. Making the Most of the African Continental Free Trade Area: Leveraging Trade and Foreign Direct Investment to Boost Growth and Reduce Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/37623 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Ekobena, Simon Yannick Fouda, Adama Ekberg Coulibaly, Mama Keita, and Antonio Pedro. 2021. Potentials of the African Continental Free Trade Area: A Combined Partial and General Equilibrium Modeling Assessment for Central Africa. African Development Review 33: 452–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, Bornhorst, and F Baum Christopher. 2001. ‘IPSHIN: Stata Module to Perform Im-Pesaran-Shin Panel Unit Root Test,’ Statistical Software Components. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s419704.html (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Fofack, Hippolyte, and Andrew Mold. 2021. The AfCFTA and African Trade—An Introduction to the Special Issue. Journal of African Trade 8: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furceri, Davide, Swarnali Ahmed Hannan, Jonathan Ostry, and Andrew Rose. 2019. Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs. IMF Working Papers 19: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusacchia, Ilaria, Jean Balié, and Luca Salvatici. 2022. The AfCFTA Impact on Agricultural and Food Trade: A Value Added Perspective. European Review of Agricultural Economics 49: 237–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geda, Alemayehu, and Addis Yimer. 2023. The Trade Effects of the African Continental Free Trade Area: An Empirical Analysis. The World Economy 46: 328–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, David M., and Roy J. Ruffin. 1996. Trade Deficits: Causes and Consequences. Economic Review-Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas 11: 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K. R. 1964. Keynesian Theory of Balance of Payments. The Indian Economic Journal 11: 367–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Robert E., and John B. Taylor. 1997. Macroeconomics, 5th ed. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Hans Grinsted, and Ron Sandrey. 2015. The Continental Free Trade Area—A GTAP Assessment. Stellenbosch: Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa (TRALAC). [Google Scholar]

- Jomit, C. P. 2014. Export Potential of Environmental Goods in India: A Gravity Model Analysis. Transnational Corporations Review 6: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbasi, Hassan. 2001. The Gravity Model and Global Trade Flows. Paper presented at the 75th International Conference on Policy Modelling for European and Global Issues, Brussels, Belgium, July 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Karingi, Stephen, and Simon Mevel. 2012. Deepening Regional Integration in Africa: A Computable General Equilibrium Assessment of the Establishment of a Continental Free Trade Area Followed by a Continental Customs Union. 332288:52. West Lafayette: Purdue University, Center for Global Trade Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Keho, Yaya. 2021. Determinants of Trade Balance in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU): Evidence from Heterogeneous Panel Analysis.” Edited by Robert Read. Cogent Economics & Finance 9: 1970870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Zakir Saadullah M., and Ismail M. Hossain. 2010. A Model of Bilateral Trade Balance: Extensions and Empirical Tests. Economic Analysis and Policy 40: 377–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korap, Levent. 2011. An Empirical Model for the Turkish Trade Balance: New Evidence from Ardl Bounds Testing Analyses. Munich Personal RePEc Archive 14: 38–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kouty, Manfred. 2021. Implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA): The Effects of Trade Procedures on Trade Flows. Research in Applied Economics 13: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Helga. 2005. A Gravity Model for Exports from Iceland. CAM Working Papers 2005-14. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, Department of Economics, Centre for Applied Microeconometrics. [Google Scholar]

- Laksono, Roosaleh Laksono, and Mohd Haizam Mohd Saudi. 2020. Analysis of the Factors Affecting Trade Balance in Indonesia. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 24: 3113–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, Maryla, Dominique van der Mensbrugghe, Maria Filipa Seara Pereira, Israel Osorio Rodarte, and Michele Ruta. 2020. The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects. Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/333178 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Ndukwe, F. O. 2004. Promoting Trade: Regional Integration and the Global Economy. In New Partnership for Africa’s Development. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, June 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ntara, Caroline K. 2016. Trading Blocs and Economic Growth: A Critical Review of the Literature. International Journal of Developing and Emerging Economies 4: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, ed. 2011. Trade for Growth and Poverty Reduction: How Aid for Trade Can Help; The Development Dimension. Paris: OECD.

- Phat, Le Trung Ngoc, and Nguyen Kim Hanh. 2019. Impact of Removing Industrial Tariffs under the European–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement: A Computable General Equilibrium Approach. Journal of Economics and Development, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, Michael, David Cheong, and Shintaro Hamanaka. 2011. Methodology for Impact Assessment of Free Trade Agreements. Manila: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, Mohammad, and Dilip Dutta. 2012. The Gravity Model Analysis of Bangladesh’s Trade: A Panel Data Approach. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business 13: 263–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygil, Mesut, Ralf Peters, and Christian Knebel. 2018. African Continental Free Trade Area: Challenges and Opportunities of Tariff Reductions. UNCTAD Blue Series Papers. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ser-rp-2017d15_en.pdf?Repec (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Shinyekwa, Isaac M. B., Enock N. W. Bulime, and Aida Kibirige Nattabi. 2021. Trade, Revenue, and Welfare Effects of the AfCFTA on the EAC: An Application of WITS-SMART Simulation Model. Business Strategy & Development 4: 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, Kazi, Umar Bamanga, and Md. Mahmudul Alam. 2018. Stata Command for Panel Data Analysis. Method. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songwe, Vera, Jamie Alexander Macleod, and Stephen Karingi. 2021. The African Continental Free Trade Area: A Historical Moment for Development in Africa. Journal of African Trade 8: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, Jan. 1963. Shaping the world economy. The International Executive 5: 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tralac. 2018. Trade Data Updates: Uganda Intra-Africa Trade and Tariff Profile. Available online: https://www.tralac.org/documents/publications/trade-data-analysis/1995-uganda-intra-africa-trade-and-tariff-profile-june-2018/file.html (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Tralac. 2022. Tralac 2022 Annual Conference Report. Available online: https://www.tralac.org/documents/events/tralac/4665-tralac-2022-annual-conference-report/file.html (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2023. Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade 2022 the Remarkable Trade Rebound of 2021 and 2022. Geneva: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, ed. 2019. Key Statistics and Trends in Regional Trade in Africa. New York and Geneva: United Nations. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctab2019d3_en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. 2020. Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area. UN. ECA. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10855/49247 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Weerasinghe, Erandi, and Tissa Ravinda Perera. 2019. Determinants of Balance of Trade in the Sri Lankan Economy. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance 10: 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2020. The African Continental Free Trade Area: Economic and Distributional Effects. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2023. Trade Has Been a Powerful Driver of Economic Development and Poverty Reduction. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade/brief/trade-has-been-a-powerful-driver-of-economic-development-and-poverty-reduction (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- World Integrated Trade Solution Data Portal. 2023. Trade Summary. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2023).

| Country | Kenya | Uganda | Tanzania | Rwanda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trade Partners | Burundi Democratic Republic of Congo Egypt Eswatini Mauritius Rwanda South Africa Tanzania Uganda Zambia | Burundi Democratic Republic of Congo Egypt Ethiopia Kenya Rwanda South Africa Sudan Tanzania Zambia | Burundi Democratic Republic of Congo Egypt Eswatini Kenya Malawi Mauritius Morocco Mozambique Rwanda South Africa Uganda Zambia | Burundi Cameroon Democratic Republic of Congo Ethiopia Kenya Malawi Tanzania Tunisia Uganda Zambia |

| Country | Variables | Obs | Mean | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | lnTBij | 193 | 1.326234 | 2.242506 | −8.119229 | 9.26279 |

| lnRPGNIji | 210 | 0.2160549 | 1.195267 | −2.124475 | 2.48567 | |

| lnRGDPji | 210 | −0.8272978 | 1.562378 | −3.660679 | 2.6534 | |

| lnDISTij | 210 | 7.334903 | 0.7293681 | 6.222874 | 8.170093 | |

| MFN trade Weighted Tariffij | 122 | 21.04924 | 15.36514 | 1.888869 | 84.50749 | |

| lnEXCHRij | 209 | −0.2217416 | 2.437015 | −3.605275 | 3.198146 | |

| lnRPji | 204 | 0.0294985 | 0.2148947 | −1.723159 | 0.5237281 | |

| Uganda | lnTBij | 207 | 0.992126 | 3.05202 | −5.77915 | 8.167259 |

| lnRPGNIji | 210 | 0.464031 | 0.944054 | −1.3207 | 2.915854 | |

| lnRGDPji | 210 | 0.443313 | 1.470261 | −2.64654 | 3.472573 | |

| lnDISTij | 210 | 7.084359 | 0.726786 | 5.929722 | 8.104289 | |

| MFN trade Weighted Tariffij | 188 | 12.98092 | 8.071677 | 0.342724 | 46.15428 | |

| lnEXCHRij | 210 | 3.581783 | 2.330288 | 0.325188 | 6.852314 | |

| lnRPji | 206 | −0.00289 | 0.392637 | −2.06667 | 2.917769 | |

| Rwanda | lnTBij | 186 | −0.80493 | 4.019844 | −14.4495 | 11.95249 |

| lnRPGNIji | 211 | −0.229929 | 0.814578 | −1.26144 | 2.403493 | |

| lnRGDPji | 211 | −0.82263 | 1.285054 | −2.57472 | 1.973745 | |

| lnDISTij | 211 | 6.989612 | 0.882561 | 5.179984 | 8.470689 | |

| MFN trade Weighted Tariffij | 151 | 20.00504 | 13.78315 | 0 | 89.87846 | |

| lnEXCHRij | 211 | 1.472818 | 2.441024 | −1.50447 | 6.13911 | |

| lnRPji | 205 | 0.067289 | 0.2964492 | −1.92725 | 1.018584 | |

| Tanzania | lnTBij | 272 | 0.7963187 | 2.789716 | −7.778935 | 8.567072 |

| lnRPGNIji | 273 | 0.4306175 | 1.128428 | −1.558972 | 2.545235 | |

| lnRGDPji | 273 | −.5543845 | 1.482554 | −3.164834 | 2.678648 | |

| lnDISTij | 273 | 7.402512 | 0.7117583 | 6.322888 | 8.752172 | |

| MFN trade Weighted Tariffij | 221 | 14.54257 | 11.85354 | 0.021007 | 83.78444 | |

| lnEXCHRij | 273 | 3.048566 | 2.114589 | −0.7200544 | 5.851021 | |

| lnRPji | 264 | −0.0558257 | 0.2429695 | −2.02887 | 0.8532615 |

| Country | EACACTIVE1 | COMESA ACTIVE 1 | SADC ACTIVE1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Kenya | 0 | 141 | 67.14 | 51 | 24.29 | ||

| 1 | 69 | 32.86 | 159 | 75.71 | |||

| total | 210 | 100.00 | 210 | 100.00 | |||

| Uganda | 0 | 133 | 63.33 | 51 | 24.29 | ||

| 1 | 77 | 36.67 | 159 | 75.71 | |||

| total | 210 | 100 | 210 | 100 | |||

| Rwanda | 0 | 153 | 72.51 | 65 | 30.81 | ||

| 1 | 58 | 27.49 | 146 | 69.19 | |||

| total | 211 | 100.00 | 211 | 100 | |||

| Tanzania | 0 | 203 | 74.36 | 126 | 46.15 | ||

| 1 | 70 | 25.64 | 147 | 53.85 | |||

| total | 273 | 100.00 | 273 | 100.00 | |||

| Kenya | Uganda | Tanzania | Rwanda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS Test | Fisher Type ADF Test | IPS Test | Fisher Type ADF Test | |||

| Ln Trade Balanceij | −2.5937 (0.0047) | −3.3426 (0.0004) | −2.7840 (0.0027) | |||

| Ln Relative GDPji | −2.5546 (0.0053) | −2.4496 (0.0072) | −3.4861 (0.0002) | −3.3403 (0.0004) | ||

| Ln Relative per capita GNIji | −2.3509 (0.0094) | −1.8246 (0.0340) | ||||

| MFN Weighted Tariffij | 54.3460 (0.0001) | 72.2212 (0.0000) | ||||

| Ln exchange rateij | −2.7862 (0.0027) | −1.9063 (0.0283) | −3.9592 (0.0000) | |||

| Ln relative priceji | −5.3095 (0.0000) | 93.6708 (0.0000) | −4.7435 (0.0000) | |||

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Natural Log of Bilateral Trade Balance (Ln TBij) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | Uganda | Tanzania | Rwanda | |||||

| Fixed Effects (fe) | Random Effects (re) | Fixed Effects (fe) | Random Effects (re) | Fixed Effects (fe) | Random Effects(re) | Fixed Effects (fe) | Random Effects (re) | |

| Ln Relative per Capita GNIji | 1.343 (1.3938) | −0.8370 (0.6402) | −2.2606 * (1.1905) | −0.1936 (0.4111) | 0.2555 (1.6687) | −0.9185 *** (0.3124) | −0.7465 (2.8348) | −2.5283 *** (0.7050) |

| Ln Relative GDPji | −3.627 ** (1.4222) | −0.1890 (0.4507) | 2.7820 ** (1.1836) | −0.17402 (0.2996) | −0.3990 (1.3553) | 0.3169 (0.2056) | −1.0971 (2.4331) | −1.3877 *** (0.4260) |

| Ln Dist. | −3.1418 ** (1.3081) | −2.1679 *** (0.5320) | 0.2581 (0.5015) | 0.4319 (0.7787) | ||||

| MFN trade Weighted Tariff | 0.0031 (0.0085) | (0.0082 (0.0086) | −0.03168 ** (0.0133) | −0.0588 *** (0.0144) | −0.0007 (0.0085) | −0.0064 (0.0091) | −0.0023 (0.0178) | −0.0017 (0.0179) |

| LnEXCHRij | 2.687 *** (0.6318) | 0.9492 ** 0.4276 | −0.2551 (0.5527) | −0.6433 *** (0.1378) | 0.4655 (0.7925) | −0.6762 *** (0.1909) | (0.2616) (1.4987) | −0.2765 (0.1732) |

| LnRPji | 3.632 *** (0.8577) | 1.3804 ** (0.6371) | 0.9135 (0.5789) | 1.1791 *** (0.3073) | 0.8472 (0.9370) | −0.5787 (0.4667) | 2.7557 (1.7885) | 2.029 ** (0.9783) |

| EAC | 0.3736 (0.5964) | −0.0281 (0.6192) | −2.852 *** (0.7066) | −4.4283 *** (0.5944) | 0.0246 ** (0.5262) | 0.0695 (0.5395) | −0.9463 (0.8323) | −1.0111 (0.7229) |

| COMESA | −2.651 *** (0.7093) | −2.6638 *** (0.6972) | 0.413084 0.546098 | 1.1101 ** (0.4452) | −0.3926 (0.7132) | −0.5498 (0.7000) | ||

| SADC | 0.6761 (0.6056) | |||||||

| _cons | 0.254557 (1.4224) | 26.30578 (9.5112) | 2.683117 1.755712 | 20.189 (3.7969) | −1.0177 (2.3566) | 1.1841 (3.6976) | −1.5586 (2.4127) | −3.0966 (5.2883) |

| Number of Obs. | 116 | 116 | 185 | 185 | 215 | 215 | 138 | 138 |

| Number of groups | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 10 |

| Hausman Test Results | chi2(7) = 32.66 Prob>chi2 = 0.0000 | chi2(7) = −14.38 chi2 < 0 ==> model does not meet asymptotic assumptions of the test | chi2(6) = 7.78 Prob>chi2 = 0.2546 | chi2(7) = 16.79 Prob>chi2 = 0.0188 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onono, P.; Omondi, F.; Mwangangi, A. Impacts of Regional Integration and Market Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Balances of Selected East African Countries: Potential Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area. Economies 2024, 12, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060155

Onono P, Omondi F, Mwangangi A. Impacts of Regional Integration and Market Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Balances of Selected East African Countries: Potential Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area. Economies. 2024; 12(6):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060155

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnono, Perez, Francis Omondi, and Alice Mwangangi. 2024. "Impacts of Regional Integration and Market Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Balances of Selected East African Countries: Potential Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area" Economies 12, no. 6: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060155

APA StyleOnono, P., Omondi, F., & Mwangangi, A. (2024). Impacts of Regional Integration and Market Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Balances of Selected East African Countries: Potential Implications of the African Continental Free Trade Area. Economies, 12(6), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12060155