Abstract

Trade is considered one of the main drivers of a country’s economic growth and development. Therefore, a successful analysis that identifies the bilateral trade flows, their determinants, and the regional integration costs and benefits opens new horizons for international trade perspectives. This study examines the effects of new and existing regional agreements on the international trade patterns of Western Balkan countries based on the Albanian case. In this regard, an extended trade gravity model is applied with a panel data set of trade flows between Albania and 43 of its regional strategic partners during the period of 2008 to 2022. This work considers two different similarity indexes to explain the effect of the economic structures of partner countries on their trade volumes: the relative factor endowment and the absolute factor endowment. The first is used to test the Linder Hypothesis, and the latter is used to test the effect of similarity in economic size between trading partners. Empirical results indicate that the effect of the selected explanatory variables, such as transportation costs, economic size, economic strength, exchange rate, and their relative as well as absolute endowment, is within expectations. Unexpectedly, the domestic economic size and strength are found to be insignificant in explaining the import flows and inversely proportional to the exports of Albania. Finally, it is indicated that trade flows are clearly dependent on traditional ties rather than on new incentives like the Open Balkan, which cannot offer a new regional center of gravity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the gravity of the Open Balkan initiative has been tested for one of the participating countries. The study concludes that while the Open Balkan initiative shows potential, the Berlin Process remains a more reliable path toward EU integration for Albania.

1. Introduction

Trade is one of the main engines driving the development and growth of an economy, as it is directly linked to the creation of better jobs, the reduction of poverty, and the diversification of economic opportunities, particularly in developing countries (Rudrappa and Veerabhadrappa 2024; Vijayasri 2013). Global economic integration allows economies across the world to be more interconnected than ever before and catalyzes the trade of goods and services among them. As a result, in addition to the great development of international trade, there has also been an increase in the role and number of international trade agreements (Baccini et al. 2011; Cremona 2010). According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), nowadays there are around 360 regional trade agreements (RTAs) of different levels of integration in force. Basically, RTAs are found to be a useful instrument for overcoming the geographical, infrastructural, and political divisions between countries in order to facilitate trade flows, the movement of people, capital exchange, and the spread of innovation (Wignaraja et al. 2012). Therefore, a successful analysis that identifies the bilateral trade flows, their determinants, and the regional integration costs and benefits opens up new horizons for a country’s trade policies.

A common tool employed for explaining bilateral trade flows between countries or regions is the trade gravity model. Starting from the very first conceptualization in the 1960s to the modern day, it represents one of the most widespread and successful frameworks for analyzing trade determinants, potentials, policies, patterns, and openness (Porto 2020). Initially, the literature on trade gravity models identified as the determinant factors of trade volumes the size of the economies, their structure, and the connectivity between partner countries. Most recently, several exogenous factors that impact trade flows, such as exchange rate, population, area, GDP per capita, foreign direct investment, number of workers, trade openness, Gini index, oil price, and similarity between economies, as well as different dummy variables for different trade agreements, contiguity, language, culture, emigration, colonies, war or political conflicts, and bilateral agreements, among others, have extended and outperformed the traditional trade gravity model (Bikker 2007, 2009; Freeman and Teulings 2020).

For more than half a century, trade flows on a global level have experienced unprecedented growth, which has had a clear upward trend over time (Blonigen et al. 2012; Marjit et al. 2019). There are several factors that are found to influence the progress of trade flows, like geographical distance, economic level, exchange rate, trade openness, governmental policies, and prices (Ronci 2004; Vollrath et al. 2009; Zannou 2010). Recent research indicates that the increase in trade flows has had a regional nature, as trade exchange is found to be stronger within regional blocks (Chortareas and Pelagidis 2004). In fact, the last few decades have been characterized by a continuous failure of multilateral trade negotiations at the WTO, pushing the concerned countries to adopt free trade agreements (FTAs) as an alternative solution (Buckley et al. 2008). For this reason, the number of FTAs increased significantly at a global level, from 50 in 1990 to more than 360 in 2023, becoming a defining feature of the new world trade system1 (Dent 2010; Matsushita and Lee 2019). The USA had the best part of the contribution to this trend due to the high number of bilateral and multilateral FTAs pursued over time in different parts of the world (Fink and Reichenmiller 2005). Furthermore, Mastel (2004) argues that FTAs are becoming one of the driving forces of their economic policy. Europe and the Asia-Pacific region represent two other key players in the pattern of preferential FTAs, with a comparable total number of concluded agreements (Horn et al. 2011; Hufbauer and Schott 2009). Other regions are also making great progress in eliminating trade barriers or are in the process of doing so (Bergsten 1996). For example, the free trade area of the African continent is expected to exceed a $2.5 trillion GDP in a market of 1.2 billion people, while that of North America spikes at around $6 trillion annually (Gathii 2019; Nahler 2009).

In the last three decades, the post-communist economy of Albania has been demonstrated to be constantly open toward regional integration in order to access new markets and fulfill the needs of the internal one (Bulaj 2018; Panagiotou 2011). The transition of Albania from a centrally planned state into an open market economy in the early 1990s was followed by a dramatic growth in trade flows (Çupi and Muça 2020). Only in the last two decades have imports grown by more than 250% and exports by more than 600%, transforming it into a strong regional and international market. According to the Albanian Institute of Statistics (INSTAT), Albanian imports and exports peaked in 2022 at about ALL 950 and ALL 487 billion of goods, increasing significantly compared with the previous year as they experienced about 19% and 32% of growth, respectively. However, the existing poor infrastructure, the lack of vision in fulfilling business needs, and the inability of the private and public sectors to adapt to the newly installed economic system became a burden for the Albanian economy in order to fulfill all expectations (Bulaj 2018). The trade balance remains negative, and it has deteriorated in these two decades by more than 130%. Furthermore, Albania failed to maximize its zone of influence, as its trade flows are found to be dependent on traditional ties with neighboring countries like Italy, Kosovo, Greece, North Macedonia, and Serbia, which cover more than 50% of imports and exports (Fetahu 2014).

The recent literature indicates several factors that explain the significant growth of trade flows in the Balkans during the last decades, including the integration of international production networks (Ganić 2013; Shimbov et al. 2016), the CEFTA regional agreement (Baranenko and Milivojevic 2012), and capital inflows (Axarloglou and Pournarakis 2005). Their main partner remains the EU, which covers around 69% of exports and 54% of imports, followed by the internal markets of the Western Balkans, Russia, China, and Turkey2. Furthermore, there are clear indicators that this trade has a great potential for further growth (Montanari 2005). However, Hysa and Nikolli (2014) put into question the importance of such growth, as they highlighted that several authors find a negative relationship between this trade and economic growth. Such results expose the complex nature of trade in the Balkans and the need for more efforts to understand the trade patterns of this region.

Even though the literature review identifies several authors who have analyzed the determinants of Albanian trade flows, research in this field remains scarce. In all cases, the range of explanatory variables is restricted, does not consider all the levels of regional integration, or suffers from the selected econometric approach. Furthermore, there is no deep discussion on the importance of new regional incentives such as the Open Balkan. As a result, there is still no clarity, and several questions about Albanian trade patterns remain unanswered. What are the determinants of Albanian trade flows? What is the effect of existing regional trade agreements (RTAs) on Albanian trade patterns? Is the Open Balkan a new possible center of gravity for Albania in their path toward EU accession? In this research, we aim to give answers to these questions by employing an extended trade gravity model and a panel data set of trade flows between Albania and 43 of its regional strategic partners during the period 2008–2022. The estimated results explain the bilateral trade flows of Albania and analyze the Albanian trade patterns in reference to the existing regional trade agreements or to future possible ones, such as those with the EU. For the first time, we assess from an economic point of view if the Open Balkan initiative has the strength to be transformed into a new regional center of gravity for the Albanian economy and become an alternative to the Berlin Process in their path toward EU accession.

The remainder of this paper continues with a broad literature review regarding trade gravity models, with a special focus on applications that analyze trade patterns in Europe, the Western Balkans, and Albania. Next, the Section 3 explores, one more time, the traditional trade gravity model, different approaches to extend it, and several econometric issues related to the model selection. The Section 4 opens with a broad analysis of the Albanian economic background and trade flows, and then it continues with a description of the data set and the model specification. Following, the estimated results are interpreted for both cases of import and export equations. In the Section 6, we summarize the conclusions of this work and provide several policy implications.

2. Literature Review

The gravity model, starting from the very first conceptualization in Tinbergen (1962) to the modern day, represents one of the most widespread and successful frameworks for analyzing the determinants of international trade and related policies (Yotov et al. 2016). It can predict well the impact of trade policy changes, particularly over the medium term (Freeman and Teulings 2020). The changes and developments of the last six decades sharpened and improved the gravity model to the point of being referred to as the workhorse of international trade (Greaney and Kiyota 2020). Several authors have proposed different specifications of the trade gravity model, resulting in a wide spectrum of applications. Baier and Bergstrand (2007), Linnemann (1966), and McCallum (1995), among others, can be considered some of the most popular applications that nowadays serve as the basis for a whole new generation of gravity models (Melnyk et al. 2018). Capoani (2023), Jadhav and Ghosh (2023), and Metin and Tepe (2021) provide a broad literature review on the trade gravity models’ theoretical foundations from their origins to the modern day.

A great deal of attention has been dedicated to the evaluation of the common economic areas and some of their typical elements, like the common market, trade facilitation, free trade agreements, and currency unification (Arghyrou 2000; Baier and Bergstrand 2007). Some authors, like Breuss and Egger (1999), Filippini and Molini (2003), and Lampe (2008), analyze the trade flows of different regions based on panel data and observe the effects of various explanatory variables. Anderson and Marcouiller (2002) consider an insecurity index in order to capture the effect of institutional quality and corruption. Recently, Holzner and Gligorov (2004) found that the absence of such institutions is associated with the phenomenon of increased informal trade, as corrupted countries generally tend to build an informal trading network among each other rather than being open to international trade (Duc et al. 2008). Their results indicate that inadequate institutions have a similar restrictive effect on trade as tariffs do. This result was in line with North (1990), who argues that even though governments have a controversial effect on economies, the presence of good institutions, trade agreements, and regional economic unions has a direct positive effect on international trade. On the other side, De Benedictis et al. (2005) found that the presence of free trade agreements between EU countries and Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) was a determinant factor in expanding trade flows. Kepaptsoglou et al. (2010) provided a comprehensive review of studies employing the gravity model and concluded that the effect of FTAs is robust and effective. The positive effect of FTAs on trade flows is further supported by Mui (2011) and Chandran (2017), who find it to be stronger among the member countries. However, the literature review indicates that there are several concerns related to the effects of FTAs. Ramaswamy et al. (2021) highlighted that certain free trade agreements might have a negative effect on trade. Empirical results further indicate that the trade gravity model overpredicts the trade expansion within FTA members (Derosa and Gilbert 2005) and that FTAs are found to be mainly beneficial to countries with higher economic potential (Yao et al. 2019).

A range of studies have employed the gravity model, which remains a simple and reliable model of factors, in analyzing EU trade patterns, identifying determinant factors of the process, and evaluating the effect of FTAs on trade (Lypko 2022; Virag-Neumann 2014). Results indicate that there is an advanced level of integration in the Euro area and that for many members, the welfare effect of the single market dominates quantitatively (Bussière et al. 2008; Felbermayr et al. 2018). For example, the Euro was estimated to increase intrablock trade flows by around 15% during 1998–2002 compared with the preceding decade (Flam and Nordström 2006; Rose 2000). Other factors that were found to have a positive direct effect on trade patterns are labor standards (Samy and Dehejia 2011), harmonization of technical regulations (Vancauteren and Weiserbs 2005), geographical distance (Leitão and Tripathi 2013), preferential policies (De Benedictis and Salvatici 2011), EU accession (Bussière et al. 2008; Stack and Pentecost 2011), and trade agreements (Spies and Marques 2009). Other studies consider several entities within Europe, such as Central and Eastern Europe (Bussière et al. 2008; Lypko 2022; Ravishankar and Stack 2014; Wang and Winters 1992), Southeast Europe (Christie 2002), selected EU candidates (Braha et al. 2015), the Baltic Sea Region (Byers et al. 2000; Cipkutė 2017; Paas and Tafenau 2005), the Mediterranean area (Kahouli and Maktouf 2015), the Eurasian Economic Space (Mogilat and Salnikov 2015), and the Western Balkan (Klimczak 2014; Pere and Ninka 2017).

After the 1990s, the literature on gravity models was mainly focused on evaluating several free trade agreements in Europe, like the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the European Union (EU), Central and Eastern European countries, and Baltic countries (BC) (De Benedictis et al. 2005). Their findings indicate that these free trade agreements resulted in a significant growth in trade flows among them. For example, Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1997) evaluated the effects of European regionalism by focusing on the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) for a four-decade period. Results indicate that European trade with the rest of the world has decreased over time. Soloaga and Winters (2001) evaluated the effect of trade blocks on trade patterns for a set of 58 countries and identified trade diversion for the EU and EFTA countries. Damijan and Masten (2002) evaluated the time-dependent efficiency of FTAs based on the trade patterns between Slovenia and other CEEC countries. They concluded that these agreements require a minimum of two to three years in order to become effective and that they are dependent on the nature of demand in the internal markets. Laaser and Schrader (2002) highlighted the significant progress made by Baltic countries in their path toward integration into Western Europe. Results indicate that the center of gravity of this process has a local nature as it is centered in the same region. Martin and Turrion (2003) evaluated the process of association agreements between OECD and EU countries by considering the trade flows between the OECD and CEECs. Their results confirmed that these agreements were a determinant factor in the new trade patterns between the EU and CEECs. Paas (2003) analyzed the trade flow patterns between EU members and Eastern European candidate countries. Results indicate that the Western and Eastern regions are weakly tied and that the trading patterns between them differ significantly. The role of the Central European Free Trade Area (CEFTA) and the Baltic Free Trade Area (BFTA) was explored by Adam et al. (2003), which highlighted their important role in the expansion of regional trade. According to the authors, the examples of CEFTA and BAFTA should be considered by CEEC countries as an alternative to their approach toward trade liberalization. Stack and Pentecost (2011) used a panel cointegration approach in their model in order to evaluate the importance and progress of European regional integration based on a sample of 12 EU members and 20 OECD countries. Sertić et al. (2024) investigated the effect of trade liberalization on trade patterns, taking as reference the implementation of such reform in Croatia during the period 2000–2021. More recently, the trade gravity model has been applied in evaluating the FTAs between EU and non-EU countries (Grübler and Reiter 2021; Jabri 2020; Tskhomelidze 2022).

In the last decades, attention has shifted to assessing the potential trade flows of Western Balkan (WB) countries as potential candidates to join the European Union (Pere and Ninka 2017). Pere and Ninka (2017) concluded that there is a clear trend among WB countries toward opening their economies and regional integration. Meanwhile, the WB region as a whole improved the levels of international trade, where the main trading partner remains the EU. They highlight the positive effects of cultural heritage, contiguity, EU ties, and large economies on these trade patterns. Montanari (2005) argued that there is a great potential for improvement in trade flows between the EU and WB and that these trade patterns depend on the geographical distance as well as the imposed trade policy. These results were confirmed by Braha et al. (2015), who found a weak performance in exports for the EU candidates. According to their gravity model, the exports depend on the size of the economy (GDP) and are reduced in proportion to the geographical distance from the trading partner. Similarly, Ristanović et al. (2020) evaluated Serbia’s trade patterns with EU countries and concluded that trade exchange depends on the distance of the trading partners. However, the economic potential of the EU countries was able to break this barrier, as trade with such developed countries is highly valued regardless of their distance. A series of studies identify several factors that impact trade flows in the WB countries. Among all, FTAs and common economic areas like EU membership (Dragutinovic-Mitrovic and Bjelić 2015), CEFTA (Dragutinovic-Mitrovic and Bjelić 2015; Matkovski et al. 2022; Toshevska-Trpchevska et al. 2022), and stabilization and association agreements (SAAs) (Mardas and Nikas 2008; Reiter and Stehrer 2021) are found to have a significant and positive contribution to boosting bilateral and regional trade flows. However, in the special case of North Macedonia, Mojsoska-Blazevski and Petreski (2010) find no additional gains from FTAs and CEFTA, in particular. Another factor of interest is the trade openness or trade facilitation. Toshevska-Trpchevska et al. (2024) investigated and confirmed the importance of the digital and sustainable component of trade facilitation measures applied in WB countries. They highlight that trade facilitation measures are important for improving trade levels. At the same time, it is also confirmed that intra-regional trade has been positively driven by social and cultural variables, economic and political activity, and technological progress (Bartlett 2008; Kaloyanchev et al. 2018; Kurtovic et al. 2017; Malaj et al. 2019).

The literature review indicates that several authors aimed to apply gravity models to evaluating Albanian trade patterns, with a special focus on the rapid economic and political developments of the last three decades. Xhepa and Agolli (2003) used an extended trade gravity model in order to evaluate trade patterns between Albania and 21 partner countries during the period 1994–2002. Results indicate that the divergence in size and the economic strength are found to be determinant factors of Albanian foreign trade, while distance is found to be a barrier to Albanian exports and imports. The authors highlight the importance of negotiating a new trading regime with EU countries in order to strengthen economic ties with such partners. Surprisingly, the trade patterns with other Balkan countries were found to be extremely marginal, pointing out the necessity of establishing a regional FTA in order to accelerate regional integration. The unexploited regional trade potential and the traditional trade ties with some EU countries were confirmed by Pllaha (2011), who analyzed trade flows between Albania and seven regional and EU partner countries. Gravity model estimates indicate optimal trade flows with the selected EU countries and marginal trade levels with regional partners, which can be improved by up to 90% compared with the actual levels. Sejdini and Kraja (2014) considered trade flows between Albania and 27 partner countries based on a trade gravity model, focusing on testing the Linder and Heckscher–Ohlin hypothesis. Braha et al. (2017) analyzed the key determinants of Albanian agricultural exports during 1996–2013 for a set of 46 importing partner countries. Regression estimates indicated a positive effect of GDP, contiguity, language similarities, exchange rate, and the presence of the diaspora on Albanian agricultural exports. Distance and all FTAs considered in this study were found to have a diminishing effect on the same. Osmani and Mitaj (2017) extended the trade gravity model with a wide range of explanatory variables in order to evaluate the trade scenarios that arise for Albania from CEFTA membership based on a sample of 21 trading partners. The results indicated that the trade creation variable was statistically insignificant as the trade exchange levels did not go beyond the normal levels. Feruni and Hysa (2020) interpreted the patterns of Albanian international trade with a special focus on the CEFTA membership. Surprisingly, even though the proposed gravity model was able to explain the Albanian trade flows by confirming the theoretical effects of GDP and distance, it indicated that the effect of CEFTA is insignificant. Merko et al. (2022) assessed the role of distance and economic size in the trade flows between Albania and 24 European trading partners during 2008–2020. Finally, Sejdari and Banda (2022) evaluated the trade patterns between Albania and 32 European reported trade countries, confirming the expected direction of the included variables: positive for GDP, negative for distance, and positive for FTA. An interesting feature of this research is the fact that the Mini Schengen Area was not a determinant factor of Albanian exports. They conclude that the trading potential of the Open Balkan Initiative is not yet considered in the existing research.

More details regarding the existing studies that evaluate Albanian trade flows are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Applications of the trade gravity model in evaluating Albanian trade flows.

3. Methods

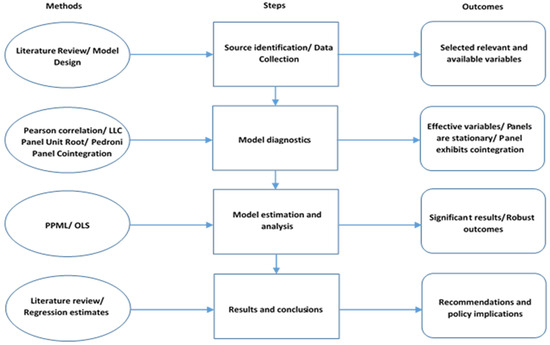

This work analyzes Albania’s trade patterns with international partner countries by employing a gravity model and panel data series. Figure 1 illustrates the four stages that compose the research process of this study, as follows:

- Stage 1: A broad literature is explored in order to identify relevant factors and econometric approaches employed in trade analysis. It continues with a summary of recent works that apply trade gravity models for the case of Albania, along with the sample selection, model, dependent and independent variables, and time period. This process enables the identification of the sources of relevant variables in explaining Albanian trade flows and the finalization of data collection.

- Stage 2: In this step, the model diagnostics are checked to assess the quality of the estimates and the validity of the assumptions.

- Stage 3: Having determined the validity of the model, in the third step, the ordinary least squares (OLS), fixed effects (FE), random effects (RE), and pseudo-Poisson maximum likelihood (PPML) are considered in estimating the regression parameters. We incorporate the OLS fixed and random estimators in order to verify the robustness of the results. The choice between the FE model, the RE model, and the pooled OLS model was determined through the Hausman test and the Breuch–Pagan Lagrange multiplier (LM). The results are first obtained through the traditional gravity equation and later through the extended one by including a range of relevant variables identified in the existing literature, such as trade potential, economic determinants, contiguity, and regional initiatives.

- Stage 4: Finally, in the last stage, the regression estimates are discussed separately for the import and export cases by comparing them with the findings of existing research. Several policy implications to alleviate critical causes are also presented.

Figure 1.

Flowchart diagram of the research process.

3.1. Classical Trade Gravity Model

The classical gravity model, also known as Tinbergen’s trade gravity model, is a powerful tool employed for analyzing bilateral trade flows and volumes (Ristanović et al. 2020). It is based on the logic of the “universal gravitation law”, which postulates that a particle in the universe attracts any other particle with a force that is proportional to their masses but inversely proportional to the square of their distance. The pioneering work of Tinbergen (1962) and Linnemann (1966) presented this idea in an economic context, as it is argued that the trade flow between two countries i and j has a positive relationship with the size of their economies (GDPs) and a negative relationship with the transportation cost, which is usually captured by the distance between them. The basic form of the gravity model is the following:

The variable denotes trade flow from country i to country j, is the GDP of country i, is the GDP of country j, is the geographical distance between their capital cities, is the constant, and , , and are the parameters of the variables. Considering that this analysis is built upon the analogy between trade flows and universal gravitational forces, Equation (1) can be rewritten in the following stochastic form in order to consider the theoretical deviations:

The term represents the random error, which is considered to be independent of the explanatory variables. The existing literature suggests the log linearization technique through natural logarithms in order to present the equation in an additive form and make it suitable for the application of different regression analysis methods:

The GDP factor as a measure of economic power is sometimes replaced by alternative elements like gross income, GDP per capita, population, or GDP based on purchasing power parity (Melnyk et al. 2018). However, the latter one is generally agreed to be the most accurate as it is able to reflect the differences among the considered countries. It is expected that the GDP will have a positive effect on trade flows as it depends directly on market demand and, as a result, on income itself (Chen et al. 2008). On the other side, the geographical distance between the capital cities, which are the economic centers of two countries, is used as a proxy for elements like transport costs and trade tariffs and is expected to have a negative effect on trade flows. This expectation is justified by the fact that trade with distant countries generally implies increased transportation costs, communication barriers, and information-sharing restrictions.

3.2. Extended Trade Gravity Model

The gravitational approach to analyzing trade flows found a wide application starting in the 1960s and was further extended by introducing new explanatory variables in order to optimize the analysis. Chen et al. (2008) classify them into two categories: (I) exogenous factors that impact trade flows, like exchange rate, population, area, GDP per capita, foreign direct investment, number of workers, trade openness, Gini index, oil price, and similarity between economies; and (II) dummy variables for different trade agreements, contiguity, language, culture, emigration, colonies, war or political conflicts, and bilateral agreements, among others. The pioneers of the revolution in this field are Anderson (1979) and Bergstrand (1985), as they were the first to introduce improvements in the classical model, followed by an abundance of approaches that aimed for a proper assessment of trade flows (Ristanović et al. 2020).

In this point of view, if we consider n-explanatory variables in the extended model, the new stochastic form, canonical and log-linearized, would be the following:

The extension of the gravity model with such relevant variables linked it with several theories of international trade (Peci et al. 2010). One of the most interesting economic conjectures that explains international trade patterns is the Linder Hypothesis (Linder 1961). It asserted that the intensity of international trade between two countries depends on the similarity of their demand structures. In other words, countries with comparable income per capita will have similar preferences for goods; as a result, these countries will develop similar industries and have increased interest in trading with each other. A common proxy for this hypothesis is the relative factor endowment (RFE), which captures the difference in income per capita between two trading countries (Martínez-zarzoso and Vollmer 2016). Considering the GDP per capita of the importer country i () and the GDP per capita of the exporter country j () in year t, the RFE index is calculated as follows (Gruber and Vernon 1970):

In theory, the coefficient of this variable is expected to be negative, as a higher value of the index means more differences in the demand structure of the two countries and, as a result, less intensity in the bilateral trade between them (Brodzicki et al. 2017). On the other side, a positive coefficient indicates that it holds the factor proportions theory (Heckscher 1919; Ohlin 1933). This economic theory, also known as the Heckscher–Ohlin model, was tested by Helpman and Krugman (1985) and Helpman (1987). It evaluates the trade patterns of a country relative to its factor abundance of production potential and natural resources. Their findings indicate that the Heckscher–Ohlin principles do not correctly explain the trade flow between industrialized countries because it is far more dependent on the countries’ similarities than their differences. Based on these two approaches, Bergstrand (1985) finds distinct roles for the total GDP and GDP per capita in explaining bilateral trade flows.

The idea of Helpman (1987) that the similarity between countries is a determinant factor of their bilateral trade flows was captured by Debaere (2005) through the following index (SIM) in Equation (7). This index ranges from 0 to 0.5, where the minimum value indicates total economic divergence and the maximum value indicates total economic convergence between each country pair. However, it was concluded that the similarity factor is more significant in explaining bilateral trade flows among more developed countries compared with the less developed ones.

International trade flows depend on the balance between production costs in the currency of the exporter and revenue in the currency of the importer. The increase in the exchange rate of a country over other countries will decrease exports as they become more expensive and, at the same time, increase imports as they become cheaper. For this reason, fluctuations in exchange rates are found to have a direct effect on trade incentives. Mehtiyev et al. (2021) argue that the effects of these fluctuations over trade are double-edged, as they can be either positive or negative. For this reason, this element has been a point of debate in different works on international trade flows. Simakova (2016) presents a broad description of the literature on both cases.

The broad literature indicates that the second group of explanatory factors, the dummy variables, is generally expected to have a positive effect on trade (Host et al. 2019). In this point of view, the existence of trade agreements, contiguity, language, culture, emigration, ex-colonies, and bilateral agreements is associated with higher levels of trade among the respective countries. However, Alhadid et al. (2022) state that the dummy variable that indicates political tensions among countries has a negative impact on trade flows.

3.3. Econometric Issues

A close overview of the existing literature in this field indicates that it was common for classical research to stick to cross-sectional analysis (Alam et al. 2009). In recent years, panel methods that combine country and time effects have found wide applications in analyzing trade flows due to their convenience and flexibility (Baltagi et al. 2024; Hsieh et al. 2022). The advantage of this approach lies in the fact that, in addition to capturing the relevant time-series relationship between variables and the unobservable individual effect between each trading pair, it also ensures increased sample size, higher variability, more degrees of freedom, and less collinearity through the independent variables (Ristanović et al. 2020). Another benefit of the panel data is that it avoids the bias generated through omitted variables, as the time-space modeling of this approach is efficient in controlling the unobserved heterogeneity (Baltagi 2005). However, it is challenging for this approach to curb the effect of unobserved heterogeneity (Hsiao 2007).

There are three common approaches used in the literature for fitting the data. (I) The fixed effect (FE) assumes correlation among the unobserved variables and the error term. This technique’s drawback is that it omits several relevant explanatory variables that are time-invariant, like the dummy variables of cultural ties, distance, and contiguity. (II) The random effect (RE) does not assume such correlation. (III) Ordinary least squares (OLS) is more efficient if the relationship between the dependent and independent variables is time-invariant (Kareem et al. 2016).

According to Motta (2019), it is common to estimate models with the log-linear specification of the gravity model. However, there are two unfortunate consequences of this approach that call it into question. First, this transformation suffers from the inconsistency of the estimates due to the presence of heteroscedasticity, which is common in panel data samples (Silva and Tenreyro 2006). And second, the existence of zero values in the panel matrix creates additional theoretical and technical issues. This is because in the original Newtonian concept, the gravitational force can never be zero regardless of the distance between two objects, while it is common to see zero trade between country pairs in specific years. Bellégo et al. (2022) provide a summary of the main issues related to zero trade scores and identify the main procedures used to overcome them. One of the pioneering and most influential approaches that directed this issue was suggested in Silva and Tenreyro (2006). They propose a simple Poisson pseudo maximum likelihood (PPML) estimator following the ideas of Winkelmann (2008) and Cameron and Trivedi (2013), which is able to address the two abovementioned issues. The comparison with the existing estimation techniques indicates that PPML is the only approach to be robust in the presence of heteroscedasticity, and it handles zero trade scores (Silva and Tenreyro 2006).

4. Data and Variables

4.1. Background

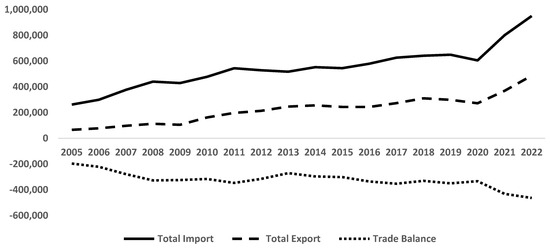

The political changes of the early 1990s led to the transition of Albania from a centrally planned state into an open market economy. As a result, it experienced a fast growth of import flows in conditions of low domestic production, which failed so far to fulfill the needs of the internal market. Only in the last two decades have import flows grown by more than 250%. During the same period, the export flows have grown dramatically, by more than 600%, transforming it into a strong regional and international exporter. However, as seen in Figure 2, the trade balance remains negative, and it keeps deteriorating over time, by more than 130%. This is mainly caused by poor infrastructure, a lack of vision in fulfilling business needs, and the inability of the private and public sectors to adapt to the newly installed economic system (Sejdini and Kraja 2014).

Figure 2.

Trade of Goods in Albania during 2005–2022 (mln ALL).

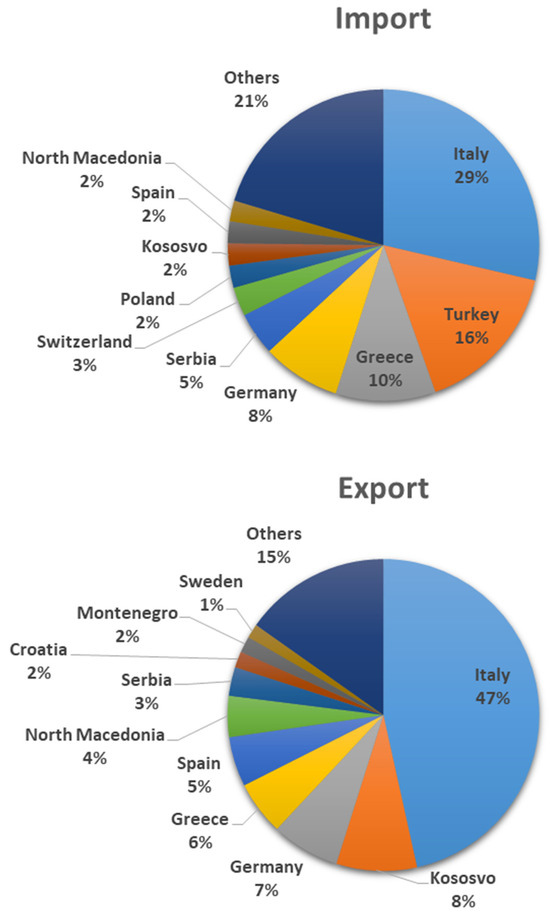

In 2022, Albanian imports and exports peaked at about ALL 950 and 487 billion of goods, increasing significantly compared with the previous year, as they experienced about 19% and 32% of growth, respectively. Figure 3 depicts the top destinations of Albanian exports and countries of origin for Albanian imports in 2022. In both cases, Italy (IT) dominates the Albanian trade market, followed by other neighboring countries like Kosovo (KS), Greece (GR), North Macedonia (MK), and Serbia (RS). Obviously, there are recorded significant shares of trade flows with other strategic European (Germany (DE), Poland (PL), Switzerland (CH), Spain (ES), and Croatia (HR)) and international (Turkey (TR), USA, China (CN), and Saudi Arabia (SA)) partners. This behavior is in accordance with existing economic theories, as the trade flow amount is generally reduced with the increase in distance between partners.

Figure 3.

Largest trading partners of Albania.

This massive expansion of the post-communist Albanian economy in the last three decades implies an increasing interest in regional integration in order to access new and alternative markets. In this way, the traditional strong attachment to the Italian, Greek, and other EU economies was extended in 2006 by increased trade flows with Western Balkan countries through the endorsement of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA)3 (Džananović et al. 2021). Even though it represents the lowest level of regional integration, it was able to replace all the existing bilateral trade agreements in the region. The next milestone toward stronger regional cooperation and fast EU integration is the Berlin Process4, which aims to foster more effective cooperation between the EU and the Western Balkans through the synchronization of monetary and fiscal policies. It represents a high-level cooperation platform between Western Balkan countries, the United Kingdom, and several EU countries like Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Croatia. The objective is to transform the Western Balkans into a mini-EU structure by gradually improving regional standards until full membership in the EU (Musliu 2021). However, the Albanian expectations were not fulfilled completely, as the European projects on infrastructure, transport, and energy required independent investment that was far beyond the country’s capabilities (Džananović et al. 2021). Other initiatives that significantly impacted cooperation between Albania and other Western Balkan countries were the Western Balkan Fund5 and the Regional Cooperation Council6.

Starting in 2019, the Western Balkan countries suffered increased Euroscepticism with the decision of the EU commission to implement a five-year moratorium on the union’s admission of new members, and especially the veto of France and the Netherlands against the opening of EU negotiations for Albania and North Macedonia (Kamberi 2021). In these conditions, the Western Balkan countries, under the initiative of Albania, Serbia, and North Macedonia in 2019, promoted the “Open Balkan”, which represents a new opportunity for regional cooperation outside the EU integration route. Even though this initiative aims to improve the level of regional cooperation through the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital among its members, it has failed so far to go beyond intergovernmental due to continuous national and international criticism7. It was limited to only three members after the categorical rejection of Kosovo and the uncertainty of the Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro governments about joining this initiative. The support was limited even from the EU side, as there is a fear of distraction from and duplication of the Berlin Process. For Albania, which stands between a possible central role in the Open Balkan initiative and the EU perspective, provided by the Berlin Process only, has come the moment to take a clear side (Kamberi 2021). From a political point of view, Kamberi (2021) argued that the only choice for the WB countries should be the Berlin Process, as their only final destination is the EU. However, it would be of interest for the stakeholders to assess from an economic point of view if the Open Balkan initiative has the strength to be transformed into a new regional center of gravity for the Albanian economy.

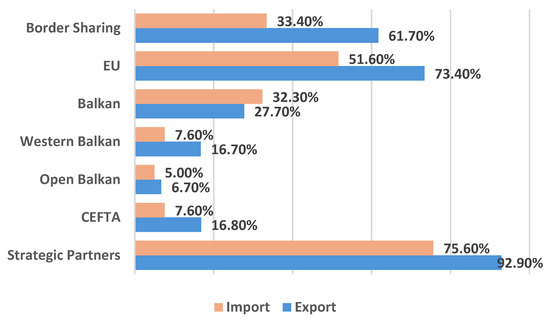

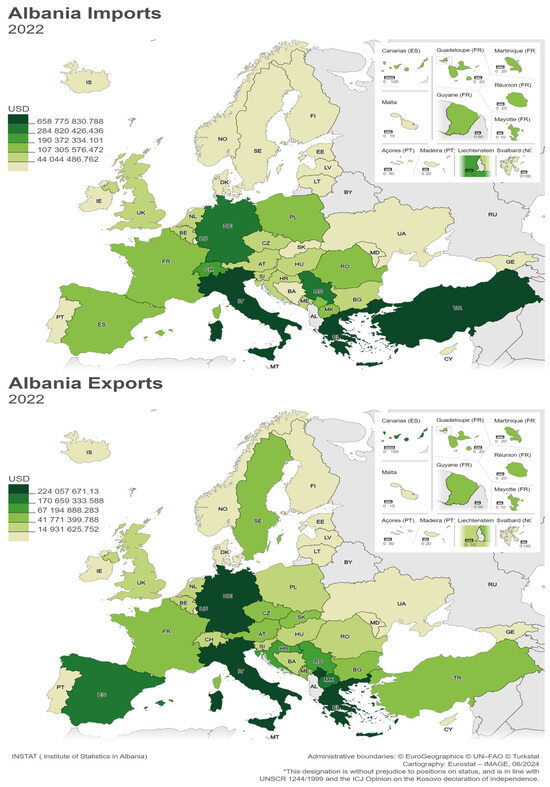

Figure 4 provides a better understanding of the share of Albanian trade flows for different levels of regional cooperation. It is obvious that the EU dominates the Albanian export and import flows, followed by the neighboring countries, all Balkan countries, CEFTA, and Western Balkan. The assumed Open Balkan partners cover the smallest share of Albanian trade flows by scoring roughly 7% of exports and 5% of imports. Considering that the focus of this work is the effect of regional integration of Albanian trade flows, we introduce the term “strategic partners” to present the 43 regional partners presented in Table 2, which are European countries, members of the Council of Europe8, or members of the EU Political Community9. These countries are the destination for 93% of Albanian exports and the countries of origin for 76% of Albanian imports, and these values are expected to grow as there are strong ties rooted in various EU strategies. Figure 5 visualizes the distribution of Albanian imports and exports across the selected regional partners.

Figure 4.

The share of Albanian trade flows for different levels of regional cooperation.

Table 2.

List of Albanian trading partners considered in this study.

Figure 5.

Albania export destination and import origin (2022).

4.2. Data Set and Models Specification

This panel study covers yearly data for Albania and 43 of its regional strategic trading partners, specified in Table 2, that cover the majority of its total imports and exports during the period 2008–2022. The panel data set includes 11610 scores corresponding to 792 observations and 18 variables considered in the study that were obtained from the Albanian Institute of Statistics (INSTAT) and the World Bank databases. Only two countries, Andorra and Liechtenstein, whose data were not available for any of the indicators, were deleted from the sample. However, the selected sample is representative enough as it contains more than 95% of the targeted partner countries. More details about the definition and the source of each variable are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Definition of key variables.

Following this terminology, the traditional and extended OLS log linear gravity model given in Equations (3) and (5) for imports and export flows can be formulated as follows:

In order to avoid eliminating zero observations in cases of no trade between Albania and partner countries in specific years, we adopt a simple and convenient fix approach by adding 1 to all import and export values. This adjustment was based on the analysis of Bellégo et al. (2022) that highlights the popularity of this approach with the assumption of small bias. Their analysis indicates that this popular fix that treats zero observations equally to the non-zero ones, although fundamentally flawed, can lead to qualitatively acceptable results. Alternative approaches, like the high-dimensional fixed effects (HDFE) and Heckman selection model, could provide more accurate estimates. However, this work employs the popular fix method in order to have comparable results with existing works that employ the same, as well as to avoid difficulties in finding identification restrictions or exclusion of variables (Gómez-Herrera 2013). Following Silva and Tenreyro (2006), the four abovementioned equations are reformulated by replacing and with and , respectively. Additionally, we run the PPML regression, where trade volumes are measured only in levels without any further transformation, as it is generally preferred to an OLS log linear model (Motta 2019).

In addition to the GDP and the distance, which are used as proxies for economic size and transport costs, respectively, the extended model employed in this work includes several other indicators that are found to be relevant in the existing literature. The GDP per capita of trading partners is included as a common factor that determines the economic strength of countries. Generally speaking, the higher the income level of trading partners, the more trade flows there are between them due to an increased strength of purchasing power (Chen et al. 2008). Obviously, the respective regression coefficient is expected to be positive. Another determinant of the trade volumes identified in the literature is the exchange rate (Sejdini and Kraja 2014). It is a crucial element in facilitating international trade as the trading partners generally use different currencies. In our case, an increased rate of ALL relative to foreign currencies may imply fewer exports due to the higher price of goods and services and more imports as they become cheaper. This work considers two different similarity indexes in order to explain the effect of the economic structures of partner countries on their trade volumes: the relative factor endowment and the absolute factor endowment. The first is used to test the Linder Hypothesis, and the latter is used to test the effect of similarity in economic size between trading partners.

The effect of regionalism on Albanian trade volumes is captured through several dummy variables that are classified into two groups. The first group presents the geographical factor through the contiguity dummy (BORD) and Balkan dummy (BAL). Normally, such countries are expected to have significant trade levels among each other due to the short distance, better transport links, and traditional and cultural ties. The second group of dummy variables captures the importance of existing (Western Balkan, CEFTA, and EU) or aimed (Open Balkan Initiative) multilateral trade agreements of Albania. The existing literature generally identifies a positive effect of such custom unions on trade flows (Hsieh et al. 2022). Table 4 depicts the summary statistics of all the variables included in the selected models.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of key variables.

5. Results

To ensure that all variables included in this study are effective, a simple Pearson correlation analysis is performed. The results are displayed in Table 5 and indicate generally low or moderate correlation levels, with the exception of two pairs of high correlation: with and with , which score more than 0.7.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficients between key variables.

Next, we check the stationarity of the variables included in the selected gravity models in order to conduct an appropriate panel regression analysis.

The results obtained from the LLC (Levin et al. 2002) panel unit root test are reported in Table 6 and confirm the stationarity of the data, which are integrated at level I(0) and at first difference I(1). In other words, for all the variables, the null hypothesis that panels contain unit roots is rejected in favor of the alternative one that panels are stationary. Furthermore, because some of the variables are not integrated into the level, we further examined the panel cointegration through the Pedroni (1999) test. In both the imports and exports models, the panel exhibits cointegration among the variables, as the null hypothesis of no integration is rejected at the 1% level for all seven respective tests. The results displayed in Table 7 confirm that the long-run relationship among the selected variables can be modeled through OLS.

Table 6.

LLC panel unit root test.

Table 7.

Pedroni panel cointegration test.

5.1. Model Selection

In this study, in addition to the PPML estimator, we also incorporate the OLS fixed and random estimators in order to verify the robustness of the results. At this point, it is necessary to choose between the fixed effect (FE) model, which is suitable for analyzing the impact of variables that vary over time; the random effect (RE) model, which, in addition to the previous one, can also handle time-invariant variables; and the pooled OLS model, also known as simple linear regression. Considering that the selected sample is a random one, we start our analysis by performing the FE and RE effect regression for each of the models 10 and 11. The Hausman test was applied under the null hypothesis that the difference in coefficients is not systematic, which indicates that the RE model is the most suitable. Results indicate that it is appropriate to use RE, as the chi statistics of these models were 9.10 and 8.19 (not significant), respectively.

With caution, it is necessary to test the presence of RE by using the Breuch–Pagan Lagrange multiplier (LM) under the null hypothesis that the variance of the RE is zero, which indicates a more appropriate pooled OLS regression. The chi statistics for each of the models 10 and 11 were 499.09 and 166.65, respectively, both significant at the 1% level of confidence. As a result, the pooled OLS was rejected in all the cases, and our analysis is built upon the models selected by the Hausman test.

5.2. Estimation Results and Analysis

After validating the selected panel data, we continue our analysis by performing the regression analysis. Table 8 presents the regression outcomes resulting from the traditional and extended gravity models based on the techniques specified in the previous section. The first and second columns report the RE estimates of the traditional and extended gravity models of Albanian imports with as the dependent variable, as a popular solution for dealing with zeros. In columns three and four, the same models are re-estimated through PPML with as the dependent variable. The remaining columns, five to eight, report similar models for the cases of exports with dependent variables and , respectively. Furthermore, we evaluate the effect of each significant variable based on the formula

as proposed by Silva and Tenreyro (2006), where is the estimated regression coefficient.

Table 8.

RE and PPML regression estimates.

5.2.1. Import Equations

A close observation of the results indicates that the RE and PPML are remarkably similar to each other in the traditional gravity model. However, in the extended models, the RE and PPML coefficients differ from each other in terms of impact and significance. PPML generally generates larger estimates, an improved number of significant variables, and a better goodness of fit as compared with 0.751 of the RE. In other words, for the PPML model, 96.4% of the variation in the input flows is explained by the variation of the selected independent variables.

The GDP-related variables, GDP and GDP per capita of Albania, are found to be not significant in explaining the import flows of Albania, opposing in this way the traditional assumptions of the gravity model theory that the size and strength of the domestic economy are determinants of trade flows (Kushtrim Braha et al. 2015; Feruni and Hysa 2020; Pllaha 2011; Xhepa and Agolli 2003). On the other side, the GDP-related variables of the partner country behave differently when measured in terms of level or scale and when the model is alternated. The GDP resulted in a positive and statistically significant coefficient, which indicates that the larger the partner country’s economy, the more imports are expected to flow into Albania from that country. The role of the economy size is larger under PPML, as the estimated elasticity is 1.777 compared with 0.957 under RE. Meanwhile, the GDP per capita of the partner country is not significant in the RE model but is negative and significant in the PPML case. In other words, the more developed the partner country, the fewer imports are expected in Albania.

Geographical distance, as was expected, is a significant factor influencing negatively the import flows of Albania, as their intensity is reduced with the distance to the trade partner. This can be explained by the fact that, generally, a higher distance means lowered transportation costs and higher information costs (Brodzicki et al. 2017). This effect is stronger in the RE case, as it is expected to reduce more than 80% of Albanian imports from distant partner countries, whereas the PPML estimates indicate an average reduction of around 70%. Pllaha (2011), who finds a similar effect of distance on trade flows, relates it to the poor transport network, the lack of traditional trade ties due to long-term isolation, and the cross-border corruption of post-communist Albania. This impact of the distance factor can be reduced through the process of regional and EU integration, which aims to create common markets and reduce trade barriers (Xhepa and Agolli 2003).

The exchange rate was found to have a small and significant positive effect on Albanian imports, opposing existing studies that find a certain independence of trade variation (Xhepa and Agolli 2003). This can be explained by the continuous strengthening of the Albanian currency (ALL) in the last 10 years, which has made the price of goods and services from partner countries cheaper.

The absolute factor endowment is found to have a positive and significant effect on Albanian imports in the PPML model only. This result is in support of Helpman’s (1987) theory, as Albania tends to import more from countries with similar economic structures and comparable levels of development. On the other side, the relative factor endowment similarity index is found to be a significant positive factor in explaining Albanian import flows in both the RE and PPML models. In other words, Linder’s (1961) hypothesis does not apply in the case of imports, as the more difference there is in demand characteristics between Albania and partner countries, the higher import flows are expected to be. This result contradicts the previous findings in Sejdini and Kraja (2014), who argue that the Linder Hypothesis holds as the RFE index of their model was found to have a significant negative sign.

The importance of geographical distance as a determinant factor in explaining import flows in Albania is confirmed by the positive and significant coefficients of the dummy variables that control for contiguity and Balkan countries. Contiguity, similarly to Sejdini and Kraja (2014) and Xhepa and Agolli (2003), is significant in the case of the PPML model, and it is expected that Albanian imports from neighboring countries will be 275% higher than from countries that do not share a border. This effect is still high even for all Balkan countries, which generally have a short distance from Albania compared with the rest of the sample. The coefficient is positive and significant in both models, indicating that Albania imports almost 144% in the RE case, and 95% in the PPML case, more from Balkan countries than other countries.

Similarly to previous studies of Albanian trade, like Pere and Ninka (2017), the EU dummy is found to have a negative coefficient and the CEFTA dummy a positive one in the PPML model. In other words, FTAs like CEFTA raise the expected Albanian imports from other member countries by more than 126%, while it is expected to have around 34% fewer imports from EU members than from other, non-EU partners. Albania imports more from a well-established market like CEFTA but less from the EU countries. It is clear that Albania, as a non-EU member, cannot benefit from the free trade flows of the common trade area and the common market rules.

Finally, results indicate that the dummy variable of Open Balkan is found to have a strong and positive effect on Albanian imports in the RE model but is not significant in the PPML model. The dummy variable that represented the six Western Balkan countries—Albania, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia—was found to be insignificant in all models and, as a result, was dropped from the model.

5.2.2. Export Equation

The results indicate that the RE and PPLM are similar to each other in the traditional gravity model, but their coefficients differ from each other in the extended model. PPML generates a higher number of significant variables and a better goodness of fit as , compared with 0.641 of the RE.

GDP and GDP per capita of Albania are found to be not significant in explaining the export flows of Albania in the PPML model, opposing in this way the traditional assumptions of the gravity model theory, like in Feruni and Hysa (2020), Pllaha (2011), Sejdari and Banda (2022), and Xhepa and Agolli (2003), that the size and strength of the domestic economy are determinants of trade flows. However, the RE model indicates that the economic size of Albania is inversely proportional to the export flows, which is well explained by the domestic economic strength. On the other side, the GDP of partner countries resulted in a positive and statistically significant coefficient, which indicates that the larger the partner country’s economy, the more exports are expected to flow from Albania toward it. The role of the economy size is smaller under PPML as the estimated elasticity is 0.705, compared with 1.562 of the RE. The effect of the GDP per capita of a partner country is found to be ambiguous, as the RE estimated elasticity is significant and positive, but it is negative in the PPML case.

Similarly to what is found in Sejdari and Banda (2022), geographical distance is a significant factor influencing negatively the export flows of Albania. On average, there are expected to be around 95% fewer Albanian exports to distant partner countries, whereas the PPML estimate is around 70%. Increasing the cost of transactions and insurance might affect the price of exported goods and services, resulting in fewer exports (Braha et al. 2015).

The exchange rate was found to have a significant negative effect on Albanian exports. As explained previously, the continuous strengthening of the Albanian currency (ALL) in the last 10 years has made the price of Albanian goods and services very expensive for the partner countries.

The absolute factor endowment has been found to have no effect on Albanian exports. Meanwhile, the role of the relative factor endowment similarity index seems to be ambiguous in explaining Albanian import flows, as the estimated elasticity is negative in the RE and positive in the PPML. The findings of the existing research (Sejdini and Kraja 2014; Xhepa and Agolli 2003) suggest that the similarity variable is negatively related to trade flows. As a result, the greater the divergences between trading markets, the more exports are expected to flow from Albania.

The importance of geographical distance as a determinant factor in explaining import flows in Albania is also confirmed in the case of exports by the positive and significant coefficient of the contiguity dummy. Exports to countries to which Albania shares a border are higher relative to the countries with which it does not share one (Mitaj and Osmani 2017). It is significant in the PPML model, and it is expected that Albanian exports to border-sharing countries will be almost 500% higher than to countries that do not share a border. However, it seems that the Albanian exports find it hard to go beyond the contiguity level. The Balkan countries that were positively affecting Albanian imports are found to have a negative effect in the case of exports. It predicts that exports to Balkan countries are almost 50% smaller than exports to other countries. This result can be explained by the fact that Balkan countries have similar market sizes and, as a result, a reduced tendency to import from each other.

Similarly to Pere and Ninka (2017), the EU dummy in PPML is found to have a positive effect on Albanian exports, predicting that exports to EU countries are expected to be almost 70% higher than to non-EU partners. The same effect is found to be greater than 225% in the RE model. Contrary to what is stated in Feruni and Hysa (2020), the CEFTA dummy is found to be positive in the PPML export model. This trade agreement, similarly to Braha et al. (2015) and Mitaj and Osmani (2017), increases the overall export potential and raises expected Albanian exports by 84%. The lack of trade barriers and the reduction in trade costs, enabled by trade liberalization, might be directly boosting export flows. Similarly, Ferataj and Nikolli (2021) found that the reduction in tax costs within the framework of the CEFTA agreement increases the purchase of goods from Albania by more than 500%.

Finally, results indicate that the dummy variable of Open Balkan is found to have a strong and positive effect on Albanian exports in the PPML model but is not significant in the RE model. PPML predicts that Albanian exports to the countries involved in this initiative are on average 178% larger than to countries that are not part of it. Similarly to the import case, the Western Balkan dummy was dropped due to not being significant in any of the models.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Regional integration is a fundamental step for Albania in its long path toward European Union accession. In a moment where the EU enlargement does not seem to get the green light, Albanian policy should be directed to other mechanisms like the Berlin Process and the Open Balkan in order to consolidate the dynamics of this process. These two initiatives cannot be operated simultaneously as they share the same objectives, so it is fundamental for Albania and other Western Balkan countries to stick to the most advantageous one. Considering that economic cooperation and the common trade area are the backbone of these initiatives, it is of great interest to further understand the economic patterns of Albania in the region and beyond. What are the global economic factors determining the regional economic cooperation of Albania? How strong is the effect of current economic relations between Albania and other partner countries? Is the Open Balkan a new center of gravity for Albania, or should it stick to the safe path of the Berlin Process? The answer to this question represents the main objectives of this research paper.

In this work, we employ a single-country trade gravity model to evaluate the determinants of Albanian imports and exports relative to 43 strategic regional trading partners, shown in Table 2, that cover the majority of its total annual imports and exports during the period 2008–2022, as indicated in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The selected period of time includes crucial political events for Albania as they work toward strengthening their position in the region, starting with NATO membership in 2009. The evaluation is performed based on the traditional and extended OLS log linear and PPML in level gravity models by using the statistical software STATA 14.2. The final regression model, in addition to the GDP and the distance, which are used as a proxy for the economic size and transport costs, respectively, is extended in order to check for the economic structures of partner countries through GDP per capita, exchange rate, and two similarity indexes and the economic integration of Albania in the region through dummy variables such as contiguity, Balkan, Western Balkan, Open Balkan, European Union, and CEFTA, as shown in Table 3.

The recent literature indicates that other factors, such as political stability, political tensions, trade policies, or technological advancement, can have a significant effect on determining a country’s trade patterns. This factor is seldom considered by existing studies that analyze Albanian exports and imports, and as a result, it can be an interesting objective of future research. However, because our main objective was to evaluate the effect of regionalism on Albanian trade volumes, we mainly focused on dummy variables that capture the role of existing (Western Balkan, CEFTA, and EU) or aimed (Open Balkan Initiative) Albanian multilateral trade agreements. The rest of the employed variables include indicators that are already found to be relevant in explaining Albanian tare patterns, as summarized in Table 1.

The results, shown in Table 8, indicate that transport costs and trade tariffs, which are captured by the geographical distance indicators, have a strong hindering effect on both Albanian imports and exports. So far, it seems that Albania has failed to diversify its trading markets by staying loyal to its traditional ties with countries such as Italy, Turkey, Kosovo, Greece, and China. This inability to further expand the trading potential in the region can be related to the poor infrastructure of Albania as well as the lack of facilities for trade procedures. As a result, stakeholders and Albanian authorities need to deeper investigate the relationship between trade patterns and “distance” factors in order to implement the necessary policies and incentives to address these issues.

The GDP-related variables of Albania are found to be not significant in explaining the import flows of Albania. Theoretically speaking, continuous GDP growth should be translated into increased production of domestic goods and services and, as a result, a reduced trade deficit. In reality, the Albanian trade deficit has increased significantly as imports grow much faster than exports. The reason for this anomaly can be found in the low degree of competitiveness of the domestic products and the inability to properly promote them in the domestic and regional markets. This logic also explains why the economic size of Albania is inversely proportional to exports, which are better explained by economic strength. However, these last results about exports should be taken with reservations due to the ambiguity across the models.

On the other side, the economic size of partner countries is found to have a positive impact on both input and output flows. This result is not a surprise, as the main trading partners of Albania that covered more than 70% of Albanian imports and exports during this period are Italy, China, Turkey, Greece, Germany, Spain, and the USA, which are relatively large economies. This is confirmed by the positive sign of the RFE index, which indicates that the Linder Hypothesis does not hold in the case of Albanian trade. However, Albania has so far failed to intensify trade with countries such as Switzerland, Ireland, Austria, the Netherlands, and all the Nordic countries, which have an economic level that is far superior to our traditional partners. Instead, the tendency is to import more from countries with similar economic structures.

Another important factor that has a great effect on the trade deficit growth of Albania is the exchange rate. The continuous appreciation of ALL currency relative to partner country currencies, especially the EUR, which is the dominant foreign currency in trade exchanges, increases the price of Albanian goods and services. In other words, it makes imports less expensive and Albanian exports more expensive in the regional markets.

Results indicate that Albanian trade flows are clearly dependent on traditional ties, such as those with neighboring countries, or on well-established trade agreements such as CEFTA. However, there seem to be some asymmetries between Albanian imports and exports when the level of regional integration is extended. The former has a local nature, as results indicate it depends more on the regional Balkan market than on the large EU market, while the latter seems to have broken the distance barrier and reached larger markets.

Even though there is some ambiguity across models, the Open Balkan countries seem to have a certain positive effect on Albanian trade flows. However, when this variable, which represents only North Macedonia and Serbia, is extended to include more countries that are aimed at being involved in this initiative, such as Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, and Montenegro, the results are insignificant. These results indicate that this initiative cannot offer a new center of gravity for Albania, which should stick to the Berlin Process as a safer gateway toward the EU market.

Western Balkan countries share several economic similarities as they represent small and underdeveloped countries whose level of investment, and consequently growth, is highly dependent on foreign savings. Trade is generally limited by poor transport infrastructure, trade barriers, corruption, and political tensions. However, the common objective is to catch up with the EU economies, and there is total agreement to reach it through intra-regional economic integration (Kaloyanchev et al. 2018). In this context, the EU represents by far the main trading partner of the WB countries, followed in second place by the intra-regional market (Pere and Ninka 2017). However, generalizing the results of this paper to other WB countries should be taken with reservations as these countries have different levels of industrialization, consumer demand, economic and technological development, size, and population (Sanfey et al. 2016).

To expand this research, future works should consider other factors of importance that may affect the trade patterns of the whole Balkan region, like corruption, the quality of governmental institutions, conflicts, language, ethnicity, and immigration, among others. The literature review indicates that such factors are significant at an international level but are seldom considered in studies about the Balkan region. Such findings can assist their public policymaking and the implementation of strategies for EU membership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and A.B.; methodology, G.Z., A.B. and A.H.; validation, G.Z., A.B. and A.H.; formal analysis, G.Z. and A.B.; resources, G.Z. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and A.H.; supervision, G.Z.; project administration, A.B. and A.H.; funding acquisition, A.B. and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the American University of the Middle East and the American College of the Middle East.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The research data considered in the study were obtained from the Albanian Institute of Statistics (https://www.instat.gov.al/al/temat/tregtia-e-jashtme/tregtia-e-jashtme-e-mallrave/, accessed on 2 March 2023) and the World Bank databases (https://data.worldbank.org/, accessed on 2 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/region_e.htm, accessed on 2 March 2023. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | https://cefta.int/, accessed on 2 March 2023. |

| 4 | https://www.berlinprocess.de/, accessed on 23 March 2023. |

| 5 | https://wbfeuproject.org/, accessed on 10 December 2023. |

| 6 | https://www.rcc.int/, accessed on 2 March 2023. |

| 7 | https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/the-open-balkan-initiative-complements-the-berlin-process, accessed on 5 March 2023. |

| 8 | https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/46-members-states, accessed on 10 April 2023. |

| 9 | https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_ATA(2022)739209, accessed on 11 January 2024. |

References

- Adam, Antonis, Dora Kosma, and Jimmy McHugh. 2003. Trade-Liberalization Strategies What Could Southeastern Europe Learn from Cefta and Bafta? IMF Working Paper, WP/03/239. Washington, DC: European Department. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, Mahmudul, Uddin Gazi, and Taufique Raziuddin. 2009. Import Inflows of Bangladesh: The Gravity Model Approach. International Journal of Economics and Finance 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alhadid, Rami, Alaa Hatoqai, and Ahmad Shalein. 2022. “Jordan’s Trade Flow Amid Regional Political Tensions”. 10. Amman. Available online: https://www.cbj.gov.jo/Default/Ar (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Anderson, James E. 1979. A Theoretical Foundation for the Gravity Equation. The American Economic Review 69: 106–16. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, James E., and Douglas Marcouiller. 2002. Insecurity and the Pattern of Trade: An Empirical Investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics 84: 342–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghyrou, Michael G. 2000. EU Participation and the External Trade of Greece: An Appraisal of the Evidence. Applied Economics 32: 151–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axarloglou, Kostas, and Mike Pournarakis. 2005. Capital Inflows in the Balkans: Fortune or Misfortune? The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 2: 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, Leonardo, Andreas Duer, Manfred Elsig, and Karolina Milewicz. 2011. The Design of Preferential Trade Agreements. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:151186765 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Baier, Scott L., and Jeffrey H. Bergstrand. 2007. Do Free Trade Agreements Actually Increase Members’ International Trade? Journal of International Economics 71: 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, Badi H. 2005. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley Publishers, vol. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, Badi H., Peter H. Egger, and Katharina Erhardt. 2024. The Econometrics of Gravity Models in International Trade. In BT—The Econometrics of Multi-Dimensional Panels: Theory and Applications. Edited by Laszlo Matyas. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 381–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranenko, Elena, and Sanja Milivojevic. 2012. Bilateral Trade Flows between Western Balkan Countries. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:58894616 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Bartlett, Will. 2008. Regional Integration and Free-Trade Agreements in the Balkans: Opportunities, Obstacles, and Policy Issues. Economic Change and Restructuring 42: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, Tamim, and Barry J. Eichengreen. 1997. Is Regionalism Rimply a Riversion? Evidence from the Evolution of the EC and EFTA. In Regionalism versus Multilateral Trade Arrangements, NBER-EASE. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 6, pp. 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellégo, Christophe, David Benatia, and Louis-Daniel Pape. 2022. Dealing with Logs and Zeros in Regression Models. arXiv arXiv:2203.11820. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten, C. Fred. 1996. Competitive Liberalization and Global Free Trade: A Vision for the Early 21st Century. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:153869667 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Bergstrand, Jeffrey H. 1985. The Gravity Equation in International Trade: Some Microeconomic Foundations and Empirical Evidence. The Review of Economics and Statistics 67: 474–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, Jacob A. 2007. An International Trade Flow Model with Substitution: An Extension of the Gravity Model. Kyklos 40: 315–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, Jacob A. 2009. An Extended Gravity Model with Substitution Applied to International Trade. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:153941231 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Blonigen, Bruce A, National Bureau, Wesley W Wilson, and Oregon June. 2012. The Growth and Patterns of International Trade. Maritime Policy & Management 40: 618–35. [Google Scholar]

- Braha, K., A. Qineti, A. Cupák, and E. Lazorcakova. 2017. Determinants of Albanian Agricultural Export: The Gravity Model Approach. AGRIS On-Line Papers in Economics and Informatics 9: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braha, Kushtrim, Artan Qineti, Sadudin Ibraimi, and Amir Imeri. 2015. Trade and integration: A gravity model of trade for selected eu candidate countries. Paper presented at the International Conference of Agricultural Economists, Milano, Italy, August 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Breuss, Fritz, and Peter Egger. 1999. How Reliable Are Estimations of East-West Trade Potentials Based on Cross-Section Gravity Analyses? Empirica 26: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]