The Path to Poverty Reduction: How Do Economic Growth and Fiscal Policy Influence Poverty Through Inequality in Indonesia?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Survey

2.1. The Relationship Between Economic Growth, Inequality, and Poverty

2.2. The Correlation Between Fiscal Policy, Inequality, and Poverty

2.3. The Correlation Between Income Inequality and Poverty

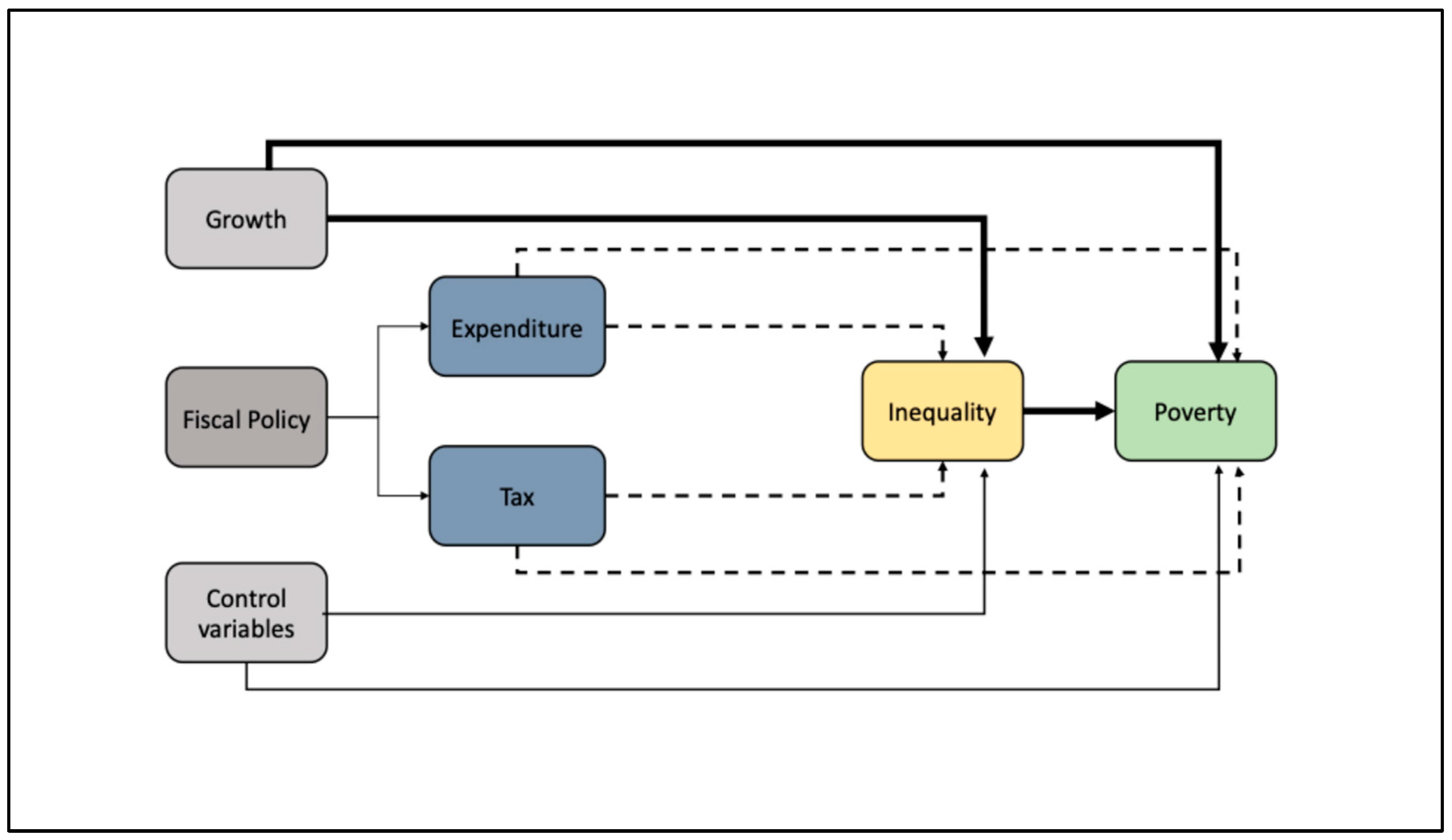

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

- GRDP per capita: This is measured via the gross regional domestic product (GRDP) per capita at nominal prices.

- Income inequality: Income inequality is measured using the Gini coefficient, which ranges from 0 to 1. A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates perfect equality, while a coefficient of 1 indicates the maximum inequality.

- Poverty: Poverty is measured with the poverty rate, defined as the percentage of the population living below the poverty line in each province. The poverty line is determined using the minimum income necessary to meet citizens’ basic needs, as defined by the BPS.

- Fiscal policy: Fiscal policy is represented by government expenditure and taxation. Government expenditure is measured as the total spending for education and health and for social assistance in millions of rupiah. Taxation is calculated as the total tax revenue collected in each province, also expressed in millions of rupiah.

3.2. Estimation Strategy and Econometric Model

- and are autoregressive coefficients (the effects of X and Y on themselves over time);

- and are cross-lagged coefficients (the effect of X on Y and vice versa);

- and are the residual errors, which are assumed to be normally distributed.

- = ;

- = (the matrix of the lagged predictors);

- = (the matrix of coefficients);

- is the covariance matrix of the errors, which is assumed to be diagonal with and as the variances of the residuals for X.

- Income Inequality Equation:where

- ○

- : Gini coefficient in province at time

- ○

- : Gini coefficient in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : poverty rate in province i at time − 1;

- ○

- : GRDP per capita in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : fiscal policy measure in province at time − 1;

- ○

- coefficients;

- ○

- : vector of control variables in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : province-specific fixed effects;

- ○

- : error term.

- Poverty Equation:where

- ○

- : poverty rate in province at time ;

- ○

- : poverty rate in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : income inequality in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : GRDP per capita in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : fiscal policy measure in province at time − 1;

- ○

- coefficients;

- ○

- : vector of control variables in province at time − 1;

- ○

- : province-specific fixed effects;

- ○

- : error term.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Regression Results for All Provinces

4.2.2. Regression Results for Heterogenous Impact on Poverty and Inequality Based on Region

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta, Pablo, Pablo Fajnzylber, and J. Humerto López. 2007. The Impact of Remittances on Poverty and Human Capital: Evidence from Latin American Household Surveys. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: http://econ.worldbank.org (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Adams, Richard H. 2003. Economic Growth, Inequality, and Poverty Findings from a New Data Set. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/f81680ff-8481-5679-9537-64a6667c2f01 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Adediyan, Aderopo Raphael, and Beatrice Onawunreyi Omo-Ikirodah. 2023. Fiscal and Monetary Policy Adjustment and Economic Freedom for Poverty Alleviation in Nigeria. Iranian Economic Review 27: 229–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamanda. 2020. The Effect of Government Expenditure on Inequality and Poverty in Indonesia. Info Artha 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Majid, Muhammad Tariq, and Muhammad Azam Khan. 2022. Economic Growth, Financial Development, Income Inequality and Poverty Relationship: An Empirical Assessment for Developing Countries. IRASD Journal of Economics 4: 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, Mary, Frank W. Agbola, and Amir Mahmood. 2023. The relationship between poverty, income inequality and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Modelling 126: 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkum, Darol, and Hattami Amar. 2022. The Influence of Economic Growth, Human Development, Poverty and Unemployment on Income Distribution Inequality: Study in the Province of the Bangka Belitung Islands in 2005–2019. Jurnal Bina Praja 14: 413–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, Simplice, and Nicholas M. Odhiambo. 2023. The effect of inequality on poverty and severity of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of financial development institutions. Politics and Policy 51: 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, Harry Azhar, Nisful Laila, and Gigih Prihantono. 2016. The Impact of Fiscal Policy Impact on Income in Equality and Economic Growth: A Case Study of District/City in Java. Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics 6: 229–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom, Katy. 2020. The Role of Inequality for Poverty Reduction Poverty and Shared Prosperity. Background Paper. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/prwp (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Bucheli, Marisa, Maximo Rossi, and Florencia Amábile. 2018. Inequality and fiscal policies in Uruguay by race. Journal of Economic Inequality 16: 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammeraat, Emile. 2020. The relationship between different social expenditure schemes and poverty, inequality and economic growth. International Social Security Review 73: 101–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerra, Valerie, Ruy Lama, and Norman Loayza. 2021. Links Between Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: A Survey. IMF Working Papers, 21/68. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- D’Attoma, Ida, and Mariagiulia Matteucci. 2024. Multidimensional poverty: An analysis of definitions, measurement tools, applications and their evolution over time through a systematic review of the literature up to 2019. Quality and Quantity 58: 3171–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Janvry, Alain, and Elisabeth Sadoulet. 2021. Development economics: Theory and practice. In Development Economics: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, Riyanto, Setyabudi Indartono, and Sukidjo. 2019. The Relationship of Indonesia’s Poverty Rate Based on Economic Growth, Health, and Education. International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding 6: 323–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnzylber, Pablo. 2018. Why Growth Alone Is Not Enough to Reduce Poverty What Can Evaluative Evidence Teach Us About Making Growth Inclusive? Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Fiszbein, Ariel, Dena Ringold, and Santhosh Srinivasan. 2011. Cash transfers, children and the crisis: Protecting current and future investments. Development Policy Review 29: 585–601. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2011.00548.x (accessed on 27 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Fosu, Augustin Kwasi. 2017. Growth, inequality, and poverty reduction in developing countries: Recent global evidence. Research in Economics 71: 306–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, Maria Jose, Maria Carmen Pérez-Lópe, and Lazaro Rodríguez-Ariza. 2020. From potential to early nascent entrepreneurship: The role of entrepreneurial competencies. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 17: 1387–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gweshengwe, Blessing, and Noor Hasharina Hassan. 2020. Defining the characteristics of poverty and their implications for poverty analysis. In Cogent Social Sciences. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis Inc., vol. 6, Cogent OA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Sean, and Claudiney Pereira. 2013. The Effects of Brazil’s High Taxation and Spending on the Distribution of Household Income. Public Finance Review 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Hal. 2021. What’s happened to poverty and inequality in Indonesia over half a century? Asian Development Review 38: 68–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, Kalle, Elia A. Machado, Andrew M. Simons, and Vis Taraz. 2022. More than a safety net: Ethiopia’s flagship public works program increases tree cover. Global Environmental Change 75: 102549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniguez-Montiel, Alberto Javier, and Takashi Kurosaki. 2018. Growth, inequality and poverty dynamics in Mexico. Latin American Economic Review 27: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Rabiul, Ahmad Bashawir Abdul Ghani, Irwanshah Zainal Abidin, and Jeya Malar Rayaiappan. 2017. Impact on poverty and income inequality in Malaysia’s economic growth. Problems and Perspectives in Management 15: 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouini, Nizar, Nora Lustig, Ahmed Moummi, and Abebe Shimeles. 2018. Fiscal Policy, Income Redistribution, and Poverty Reduction: Evidence from Tunisia. Review of Income and Wealth 64: S225–S248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, Nanak, and Ernesto M. Pernia. 2000. What is pro-poor growth? Asian Development Review 18: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, Nanak, Brahm Prakash, and Hyun Son. 2000. Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: An Introduction. In Asian Development Review. Singapore: World Scientific, vol. 18, Available online: www.worldscientific.com (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Kouadio, Hugues Kouassi, and Lewis Landry Gakpa. 2022. Do economic growth and institutional quality reduce poverty and inequality in West Africa? Journal of Policy Modeling 44: 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunawotor, Mark Edem, Godfred Alufar Bokpin, Patrick Asuming, and Kofi A. Amoateng. 2022. The distributional effects of fiscal and monetary policies in Africa. Journal of Social and Economic Development 24: 127–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, Simon. 1963. Quantitative Aspects of the Economic Growth of Nations: VIII. Distribution of Income by Size. Economic Development and Cultural Change 11: 2. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1152605 (accessed on 28 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lakner, Crishtoph, Daniel Gerszon Mahler, Mario Negre, and Espen Beer Prydz. 2022. How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? Journal of Economic Inequality 20: 559–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechheb, Houda, Ouakil Hicham, and Jouilil Youness. 2019. Economic Growth, Poverty, and Income Inequality. The Journal of Private Equity 23: 137–45. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26864455 (accessed on 27 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Nora. 2018. Fiscal Policy, Income Redistribution, and Poverty Reduction in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. New Orleans: Tulane University. Available online: http://www.commitmentoequity.org/publications-ceq-handbook/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Lustig, Nora, Carola Pessino, and John Scott. 2014. The Impact of Taxes and Social Spending on Inequality and Poverty in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay: Introduction to the Special Issue. Public Finance Review 42: 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, John W., George Davey Smith, Georgea A. Kaplan, and Jame S. House. 2000. Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ: British Medical Journal 320: 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malla, Manwar Hossein, and Pairote Pathranarakul. 2022. Fiscal Policy and Income Inequality: The Critical Role of Institutional Capacity. Economies 10: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, Gustavo A., and Luis Servén. 2022. Growth, inequality and poverty: A robust relationship? Empirical Economics 63: 725–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, Daisuke. 2023. Public debt and income inequality in an endogenous growth model with elastic labor supply. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies 17: 447–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, Jose G. 2010. The pattern of growth and poverty reduction in China. Ravallion Journal of Comparative Economics 38: 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musibau, Hammed Oluwaseyi, Abdulrasheed Zakari, and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary. 2024. Exploring the Fiscal policy-income inequality relationship with Bayesian model averaging analysis. Economic Change and Restructuring 57: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursini, Nursini. 2020. Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Development Studies Research 7: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursini, Nursini, Agussalim Agussalim, Sultan Suhab, and Tawakkal Tawakkal. 2018. Implementing Pro Poor Budgeting in Poverty Reduction: A Case of Local Government in Bone District, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 8: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nursini, Nursini, and Tawakkal Tawakkal. 2019. Poverty Alleviation in The Context of Fiscal Decentralization in Indonesia. Economics & Sociology 12: 270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, Anis. 2023. Inequality and the impact of growth on poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: A GMM estimator in a dynamic panel threshold model. Regional Science Policy and Practice 15: 1373–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Liyanage Devangi H., and Grace H. Y. Lee. 2013. Have economic growth and institutional quality contributed to poverty and inequality reduction in Asia? Journal of Asian Economics 27: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Dwight Heald, Steven Radelet, David L. Lindauer, and Steven A. Block. 2013. Economics of Development, 7th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Ravallion, Martin. 2001. Growth, Inequality and Poverty: Looking Beyond Averages. World Development 29: 1803–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, Martin, and Shaouha Chen. 2022. Is that really a Kuznets curve? Turning points for income inequality in China. Journal of Economic Inequality 20: 749–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, Jaleleddine Ben. 2012. Poverty, Growth and Inequality in Developing Countries Make a Submission Information. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 2: 470–79. [Google Scholar]

- Soava, Georgeta, Anca Mehedintu, and Mihaela Sterpu. 2020. Relations between income inequality, economic growth and poverty threshold: New evidences from EU countries panels. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 26: 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics of Indonesia. 2024. Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/en/publication/2024/02/28/c1bacde03256343b2bf769b0/statistical-yearbook-of-indonesia-2024.html (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Tanjung, Ali Mukti, and Didin Muhafidin. 2023. The Impact of The Policy of Increased Business and Property Tax on The Increase in the Poverty Rate in Indonesia. Cuadernos de Economía 46: 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tridico, Pasqualer. 2010. Growth, inequality and poverty in emerging and transition economies. Transition Studies Review 16: 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmanova, Aziza. 2023. The impact of economic growth and fiscal policy on poverty rate in Uzbekistan: Application of neutrosophic theory and time series approaches. International Journal of Neutrosophic Science 21: 107–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, Julia, and Nataliya Larionova. 2015. Macroeconomic and Demographic Determinants of Household Expenditures in OECD Countries. Procedia Economics and Finance 24: 727–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkovska, Ivana, and Borce Trenovski. 2023. Economic growth or social expenditure: What is more effective in decreasing poverty and income inequality in the European Union—A panel VAR approach. Public Sector Economics 47: 111–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Qiang, Ting Yang, and Rongrong Li. 2023. Does income inequality reshape the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis? A nonlinear panel data analysis. Environmental Research 216: 114575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, Eko, and Hidayat Amir. 2017. The Sources of Income Inequality in Indonesia: A Regression-Based Inequality Decomposition. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI). Available online: www.adbi.org (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- World Bank. 2020. Poverty & Inequality Context. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/108171597378171969/Revisiting-the-Impact-of-Government-Spending-and-Taxes-on-Poverty-and-Inequality-in-Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Yusuf, Arief Anshory, and Andy Sumner. 2015. Growth, Poverty and Inequality under Jokowi. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 51: 323–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gini | 476 | 0.359 | 0.041 | 0.245 | 0.459 |

| Poverty Rate | 476 | 11.386 | 6.139 | 3.42 | 36.8 |

| Ln GRDP per Capita | 476 | 3.489 | 0.573 | 2.232 | 5.258 |

| Ln Govt Expenditure for Education and Health | 476 | 8.899 | 0.897 | 5.878 | 11.134 |

| Ln Govt Expenditure on Social Safety Net | 476 | 5.602 | 0.766 | 3.227 | 8.268 |

| Ln Tax Revenue | 476 | 7.548 | 1.371 | 2.678 | 10.683 |

| Ln Investment | 476 | 8.868 | 1.686 | 3.195 | 12.282 |

| Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) | Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) | Indirect Effect on Poverty Through Inequality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inequalityt−1 | 0.8335 *** | 1.3333 | |

| (0.0269) | (0.8742) | ||

| Povertyt−1 | 0.0006 *** | 0.9355 *** | |

| (0.0002) | (0.0071) | ||

| lnGRDPper capitat−1 | 0.0001 | −0.2013 *** | 0.0001 |

| (0.0023) | (0.0736) | (0.0019) | |

| Taxt−1 | 0.0070 *** | −0.0219 | 0.0058 ** |

| (0.0018) | (0.0587) | (0.0015) | |

| Gov Education and Healtht−1 | −0.0073 * | −0.3074 ** | −0.0061 * |

| (0.0041) | (0.1313) | (0.0034) | |

| Gov Social Assistancet−1 | 0.0006 | 0.4427 *** | 0.0005 |

| (0.0036) | (0.1172) | (0.003) | |

| Investmentt−1 | −0.0008 | 0.0197 | −0.0007 |

| (0.0010) | (0.0316) | (0.0008) | |

| COVID-19t−1 | −0.0015 | 0.4137 *** | −0.0013 |

| (0.0024) | (0.0771) | (0.002) | |

| Constant | 0.0667 *** | 0.7547 | |

| (0.0196) | (0.6343) | ||

| N | 476 | 476 | 476 |

| Java Provinces | Non-Java Provinces | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) | Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) | Indirect Effect on Poverty Through Inequality | Inequality Equation (Direct Effect) | Poverty Equation (Direct Effect) | Indirect Effect on Poverty Through Inequality | |

| Inequalityt−1 | 0.7175 *** | 0.4253 | 0.7975 *** | 2.3991 ** | ||

| (0.0704) | (2.0755) | (0.0321) | (1.0854) | |||

| Povertyt−1 | 0.0005 | 0.9354 *** | 0.0008 *** | 0.9311 *** | ||

| (0.0009) | (0.0247) | (0.0002) | (0.0079) | |||

| lnGRDPper capitat−1 | 0.0082 | −0.2131 | 0.0035 | 0.0013 | −0.2553 *** | 0.0031 |

| (0.0062) | (0.1767) | 0.0172 | (0.0026) | (0.0848) | (0.0064) | |

| Taxt−1 | −0.0079 | 0.2781 | −0.0034 | 0.0034 | 0.0445 | 0.0082 |

| (0.0105) | (0.3019) | (0.0170) | (0.0022) | (0.0723) | (0.0064) | |

| Gov Education and Healtht−1 | −0.0034 | −0.2622 | −0.0014 | −0.0044 | −0.3810 ** | −0.0106 |

| (0.0100) | (0.2869) | (0.0082) | (0.0050) | (0.1671) | (0.0129) | |

| Gov Social Assistancet−1 | 0.0064 | 0.2333 | 0.0027 | −0.0026 | 0.5324 *** | −0.0062 |

| (0.0060) | (0.1728) | (0.0135) | (0.0045) | (0.1502) | (0.0112) | |

| Investmentt−1 | −0.0001 | −0.1083 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0274 | 0.0005 |

| (0.0028) | (0.0799) | (0.0012) | (0.0011) | (0.0367) | (0.0026) | |

| COVID-19t−1 | 0.0041 | 0.4969 *** | 0.0017 | −0.0032 | 0.3858 *** | −0.0077 |

| (0.0043) | (0.1255) | (0.0087) | (0.0028) | (0.0945) | (0.0076) | |

| Constant | 0.1452 *** | 0.4036 | 0.0828 *** | 0.2685 | ||

| (0.0450) | (1.3008) | (0.0234) | (0.7799) | |||

| N | 98 | 98 | 378 | 378 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agussalim, A.; Nursini, N.; Suhab, S.; Kurniawan, R.; Samir, S.; Tawakkal, T. The Path to Poverty Reduction: How Do Economic Growth and Fiscal Policy Influence Poverty Through Inequality in Indonesia? Economies 2024, 12, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12120316

Agussalim A, Nursini N, Suhab S, Kurniawan R, Samir S, Tawakkal T. The Path to Poverty Reduction: How Do Economic Growth and Fiscal Policy Influence Poverty Through Inequality in Indonesia? Economies. 2024; 12(12):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12120316

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgussalim, Agussalim, Nursini Nursini, Sultan Suhab, Randi Kurniawan, Salman Samir, and Tawakkal Tawakkal. 2024. "The Path to Poverty Reduction: How Do Economic Growth and Fiscal Policy Influence Poverty Through Inequality in Indonesia?" Economies 12, no. 12: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12120316

APA StyleAgussalim, A., Nursini, N., Suhab, S., Kurniawan, R., Samir, S., & Tawakkal, T. (2024). The Path to Poverty Reduction: How Do Economic Growth and Fiscal Policy Influence Poverty Through Inequality in Indonesia? Economies, 12(12), 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12120316