Development Aid and Export Resilience in Developing Countries: A Reference to Aid for Trade

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Motivation

3. Measurement of Export Resilience

(0.308) (1.053)

4. Model Specification

5. Econometric Approach

6. Interpretation of Empirical Outcomes

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| RESIL | Indicator of Export Resilience | Author’s computation—see Section 3 |

| PCI | The overall Productive Capacity Index. It measures the level of productive capacities along three pillars: “the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages which together determine the capacity of a country to produce goods and services and enable it to grow and develop” (UNCTAD 2006). It is computed as a geometric average of eight domains or categories, namely: information communication and technologies (ICTs), structural change, natural capital, human capital, energy, transport, the private sector, and institutions. Each category index is obtained from the principal components extracted from the underlying indicators, weighted by their capacity to explain the variance of the original data. The category indices are normalized into 0–100 intervals. | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Statistics portal: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx (accessed on 10 March 2021) See UNCTAD (2020) for a complete description of the methodology used to compute the indicator “PCI”. |

| ODA, AfTTOT, AfTINFRA, AfTPROD, AfTPOL | “ODA” is the real gross disbursements of the total Official Development Assistance (ODA), expressed in constant USD, 2018 prices. “AfTTOT” is the total real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade. “AfTINFRA” is the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade allocated to the build-up of economic infrastructure. “AfTPROD” is the real gross disbursements of Aid for Trade for building productive capacities. “AfTPOL” is the real gross disbursements of Aid allocated for trade policies and regulation. All four AfT variables are expressed in constant USD, 2018 prices. | Author’s calculation based on data extracted from the OECD statistical database on development, in particular, the OECD/DAC-CRS (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/Donor Assistance Committee)-Credit Reporting System (CRS). Aid for Trade data cover the following three main categories (the CRS Codes are in brackets): Aid for Trade for Economic Infrastructure (“AfTINFRA”), which includes transport and storage (210), communications (220), and energy generation and supply (230); Aid for Trade for Building Productive Capacity (“AfTPROD”), which includes banking and financial services (240), business and other services (250), agriculture (311), forestry (312), fishing (313), industry (321), mineral resources and mining (322), and tourism (332); and Aid for Trade policy and regulations (“AfTPOL”), which includes trade policy and regulations and trade-related adjustment (331). |

| NonAfTTOT | This is the measure of the development aid allocated to sectors in the economy other than the trade sector. It has been computed as the difference between the gross disbursements of total ODA and the gross disbursements of total Aid for Trade (both being expressed in constant prices 2018, USD). | Author’s calculation based on data extracting from the OECD/DAC-CRS database. |

| EXPORT | Exports of goods and services (constant 2010 USD) | World Bank Indicators (WDI) |

| EVI | This is indicator of structural economic vulnerability, also referred to as the Economic Vulnerability Index. It has been set up by the United Nations, specifically, the Committee for Development Policy (CDP), and has been used by the latter as one of the criteria for identifying LDCs. It has been computed on a retrospective basis for 145 developing countries (including 48 LDCs) by the “Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement International (FERDI)”. The EVI has been computed as the simple arithmetic average of two sub-indexes, namely, the intensity of exposure to shocks (exposure sub-index) and the intensity of exogenous shocks (shocks sub-index). These two sub-indexes have been calculated using a weighted average of different component indexes, with the sum of the components’ weights equalling one so that the values of EVI range between 0 and 100. For further details on the computation of the EVI, see for example Feindouno and Goujon (2016). | Data on EVI is extracted from the database of the Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement International (FERDI)—see online at: https://ferdi.fr/donnees/un-indicateur-de-vulnerabilite-economique-evi-retrospectif (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| TOTREV | This is the share of total public revenue (excluding grants and social contributions) in GDP. This variable is not expressed as a percentage. | Public Revenue Dataset developed by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). See online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/government-revenue-dataset (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| OPEN | This is the indicator of trade openness, measured by the share of the sum of exports and imports of goods and services in GDP. This variable is not expressed as a percentage. | Authors’ calculation based on data extracted from the WDI. |

| GDPC | Per capita Gross Domestic Product (constant 2010 USD). | WDI |

| TP | This is the indicator of trade policy, measured by the trade freedom score. The latter is a component of the Economic Freedom Index. It is a composite measure of the absence of tariff and non-tariff barriers that affect imports and exports of goods and services. The trade freedom score is graded on a scale of 0 to 100, with an increase in value indicating lower trade barriers (i.e., higher trade liberalization, whereas a decrease in value reflects increasing trade protectionism). | Heritage Foundation (see Miller et al. 2021) |

| FINPOL | This is the measure of financial policy (i.e., de jure financial openness). | This index has been computed by Chinn and Ito (2006) and was updated in July 2020. Its value ranges between 0 and 1. See: http://web.pdx.edu/~ito/Chinn-Ito_website.htm (accessed on 10 March 2021). For the purpose of the present study, we have transformed this index by multiplying its values by 100; thus, here, its values range between 0 and 100. |

Appendix B

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESIL | 327 | 0.108 | 0.252 | −0.868 | 1.443 |

| EXPORT | 327 | 44200 | 87100 | 76 | 559000 |

| EVI | 327 | 31.44 | 10.806 | 9.2242 | 70.045 |

| ODA | 327 | 967 | 1060 | 11 | 6090 |

| AfTTOT | 327 | 294 | 475 | 0.054762 | 3650 |

| AfTINFRA | 327 | 182 | 331 | 0.01176 | 3110 |

| AfTPROD | 327 | 107 | 179 | 0.016798 | 1890 |

| AfTPOL | 325 | 5.0352 | 15.2 | 0.001103 | 248 |

| NonAfTTOT | 327 | 673 | 680 | 11 | 3610 |

| PCI | 325 | 26.935 | 4.787 | 15.428 | 37.281 |

| TOTREV | 289 | 0.193 | 0.088 | 0.062 | 0.776 |

| OPEN | 327 | 0.729 | 0.319 | 0.199 | 2.043 |

| TP | 327 | 71.094 | 9.691 | 32.733 | 89.000 |

| FINPOL | 327 | 0.396 | 0.327 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| GDPC | 327 | 3960.701 | 3889.988 | 212.472 | 19,111.660 |

Appendix C

| Full Sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| Algeria | Gabon | Mozambique |

| Angola | Gambia, The | Myanmar |

| Argentina | Georgia | Namibia |

| Armenia | Ghana | Nepal |

| Bangladesh | Guatemala | Nicaragua |

| Belize | Guinea | Niger |

| Benin | Guinea-Bissau | Nigeria |

| Bhutan | Haiti | Oman |

| Bolivia | Honduras | Pakistan |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | India | Panama |

| Brazil | Indonesia | Paraguay |

| Burkina Faso | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Peru |

| Burundi | Jamaica | Philippines |

| Cabo Verde | Jordan | Rwanda |

| Cambodia | Kazakhstan | Senegal |

| Cameroon | Kenya | Sierra Leone |

| Central African Republic | Kyrgyz Republic | South Africa |

| Chad | Lao PDR | Sri Lanka |

| Chile | Lebanon | Sudan |

| Colombia | Lesotho | Tanzania |

| Comoros | Liberia | Thailand |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | Libya | Togo |

| Congo, Rep. | Madagascar | Tunisia |

| Costa Rica | Malawi | Turkey |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Malaysia | Uganda |

| Dominican Republic | Mali | Uruguay |

| Ecuador | Mauritania | Uzbekistan |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | Mauritius | Venezuela, RB |

| El Salvador | Mexico | Vietnam |

| Equatorial Guinea | Mongolia | Zambia |

| Eswatini | Mrocco | Zimbabwe |

| 1 | Information on the launch of this indicator can be found online at: https://unctad.org/fr/node/32056 (accessed on 10 March 2021). |

| 2 | The category of LDCs has been designated as such by the United Nations, and is used to refer to the poorest and most vulnerable countries to external and environmental shocks (for further information on LDCs, see online at: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/least-developed-countries (accessed on 10 March 2021)). |

| 3 | See the OECD document online at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/What-is-ODA.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021). |

| 4 | These included, for example, the insufficient development of hard and soft infrastructure that increases trade costs and erodes countries’ competitiveness in the international trade market. |

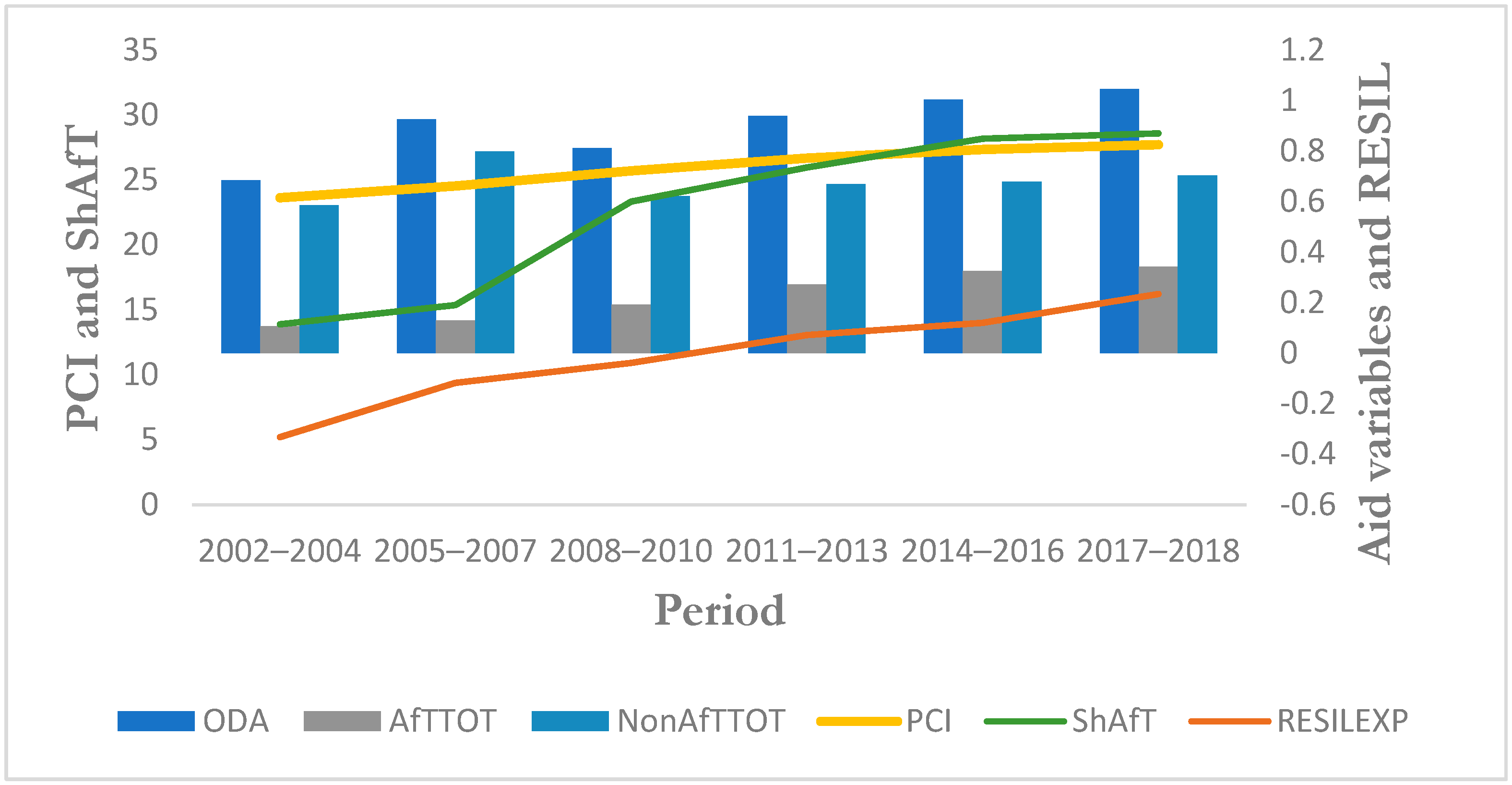

| 5 | As used in the empirical analysis, data has been averaged over non-overlapping sub-periods of three years. These sub-periods are: 2002–2004; 2005–2007; 2008–2010; 2011–2013; 2014–2016; and 2017–2018. |

| 6 | As mentioned earlier, there is no theoretical framework on the determinants of export resilience. |

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Fabrizio Zilibotti. 1997. Was prometheus unbound by chance? Risk, diversification, and growth. Journal of Political Economy 105: 709–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, James Robinson, and Yunyong Taicharoen. 2003. Institutional causes, macroeconomic symptoms: Volatility, crises and growth. Journal of Monetary Economics 50: 49–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aditya, Anwesha, and Rajat Acharyya. 2015. Trade liberalization and export diversification. International Review of Economics & Finance 39: 390–410. [Google Scholar]

- Agenor, Pierre-Richard. 2003. Benefits and costs of international financial integration: Theory and facts. The World Economy 26: 1089–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, Philippe, Akcigit Ufuk, and Howitt Peter. 2015. The Schumpeterian Growth Paradigm. Annual Review of Economics 7: 557–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aghion, Philippe, Emmanuel Farhi, and Kharroubi Enisse. 2019. Monetary Policy, Product Market Competition and Growth. Economica 86: 431–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Abri, Almukhtar. 2013. Real exchange rate volatility, terms-of-trade shocks, and financial integration in primary-commodity exporting economies. Economics Letters 120: 126–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, Almukhtar, and Baghestani Hamid. 2015. Foreign investment and real exchange rate volatility in emerging Asian countries. Journal of Asian Economics 37: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiti, Mary, and Weinstein David E. 2011. Exports and Financial Shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1841–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2001. Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzleí. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 8079. Cambridge: NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Martin, and Johansson Sara. 2010. Human capital and the structure of regional export flows. Technology in Society 32: 230–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderton, Robert, Benedetta Di Lupidio, and Jarmulska Barbara. 2020. The impact of product market regulation on productivity through firm churning: Evidence from European countries. Economic Modelling 91: 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Dan, and Saia Alessandro. 2017. Coping with Creative Destruction: Reducing the Costs of Firm Exit. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1353. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ariss, Rima Turk. 2016. Legal Systems, Capital Structure, and Debt Maturity in Developing Countries. Corporate Governance 24: 130–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheghian, Parviz, and Saidi Reza. 2002. Commodity Concentration and Export Earning Instability: The Case of Venezuela. Development Policy Review 17: 419–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auboin, Marc, and Meier-Ewert Moritz. 2003. Improving the Availability of Trade Finance during Financial Crises. WTO Discussion Paper. Geneva: World Trade Organization, Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/discussion_papers2_e.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Bacchetta, Marc, Bekkers Eddy, Piermartini Roberta, Rubinova Stela, Stolzenburg Victor, and Xu Ankai. 2021. COVID-19 and Global Value Chains—A Discussion of Arguments on Value Chain Organization and the Role of the WTO. WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2021-3. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, Dany, and Santos Miguel A. 2018. One more resource curse: Dutch disease and export concentration. Journal of Development Economics 132: 102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balavac, Merima, and Pugh Geoff. 2016. The link between trade openness, export diversification, institutions and output volatility in transition countries. Economic Systems 40: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, Richard, and Evenett Simon. 2020. Introduction. In COVID-10 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work. Edited by Richard Baldwin and Simon J. Evenett. A VoxEU.org eBook. London: CEPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Richard, and Tomiura Eiichi. 2020. Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19. In Economics in the Time of COVID-19. Edited by Baldwin and Weder di Mauro. A VoxEU.org eBook. London: CEPR Press, chp. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Barkas, Panagiotis, Honeck Dale, and Colomer Ester Rubio. 2020. International Trade in Travel and Tourism Services: Economic Impact and Policy Responses during the COVID-19 Crisis. Staff Working Paper ERSD-2020-11. Geneva: World Trade Organization (WTO). [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, Pepita, May van Schalkwyk, McKee Martin, Labonté Ron, and Stuckler David. 2021. COVID-19 and the collapse of global trade: Building an effective public health response. The Lancet Planetary Health 5: e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, Maria. 2020. The effect of communication and energy services reform on manufacturing firms’ innovation. Journal of Comparative Economics 48: 339–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassanini, Andrea, and Romain Duval. 2007. The determinants of unemployment across OECD countries: Reassessing the role of policies and institutions. OECD Economic Studies 2007: 7–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belhadi, Amine, Kamble Sachin, Chiappetta Jose Charbel Jabbour, Gunasekaran Angappa, Ndubisi Nelson Oly, and Venkatesh Mani. 2021. Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 163: 120447. [Google Scholar]

- Bleaney, Michael, and David Greenaway. 2001. The Impact of Terms of Trade and Real Exchange Volatility on Investment and Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Economics 65: 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowen, Alex, Cochrane Sarah, and Fankhauser Sameul. 2012. Climate change, adaptation and economic growth. Climatic Change 113: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bravo-Ortega, Claudio, and Julian Di Giovanni. 2006. Remoteness and Real Exchange Rate Volatility. IMF Economic Review 53: 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Briguglio, Lino, Cordina Gordon, Farrugia Nadia, and Vella Stephanie. 2009. Economic Vulnerability and Resilience: Concepts and Measurements. Oxford Development Studies 37: 229–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, Gillian, and Healy Adrian. 2018. Innovation and regional economic resilience: An exploratory analysis. The Annals of Regional Science 60: 265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brun, Jean-François, Carrère Celine, Guillaumont Patrick, and Jaime de Melo. 2005. Has Distance Died? Evidence from a Panel Gravity Model. World Bank Economic Review 19: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calì, Massimiliano, and Dirk Willem te Velde. 2011. Does Aid for Trade Really Improve Trade Performance? World Development 39: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanho, da Costa Neto N., and Romeu Rafael. 2011. Did Export Diversification Soften the Impact of the Global Financial Crisis? IMF Working Paper WP/11/99. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Canh, Nguyen Phuc, and Thanh Su Dinh. 2020. The Dynamics of Export Diversification, Economic Complexity and Economic Growth Cycles: Global Evidence. Foreign Trade Review 57: 234–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, Riccardo, Montobbio Fabio, and Morrison Andrea. 2021. Unemployment resistance across EU regions: The role of technological and human capital. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 31: 147–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiah, Mardy, and Zhong Angel. 2020. Trading from home: The impact of COVID-19 on trading volume around the world. Finance Research Letters 37: 101784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, Menzie, and Ito Hiro. 2006. What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions, and Interactions. Journal of Development Economics 81: 163–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coe, David, Subramanian Arvin, Natalia Tamirisa, and Bhavnani Rikhil. 2002. The Missing Globalisation Puzzle. IMF Working Paper WP/02/171. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Coelli, Federica, Moxnes Andreas, and Ulltveit-Moe Karen Helene. 2016. Better, Faster, Stronger: Global Innovation and Trade Liberalization. The Review of Economics and Statistics 104: 205–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveri, Andrea, Cozza Claudio, Nascia Leopoldo, and Zanfei Antonello. 2020. Supply chain contagion and the role of industrial policy. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics 47: 467–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Rob, Kozul-Wright Richard, Banga Rashmi, Capaldo Jeronim, and Gallogly-Swan Katie. 2021. Reforming the International Trading System for Recovery, Resilience and Inclusive Development. UNCTAD Research Paper No. 65-UNCTAD/SER.RP/2021/8. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola, Francesca, and Tan Shawn. 2017. Firms’ Export Decisions: Demand Trumps Financial Shocks. Policy Research Working Paper Series 7953; Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, Alan V. 2014. Local comparative advantage: Trade costs and the pattern of trade. International Journal of Economic Theory 10: 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- del Rosal, Ignacio. 2019. Export diversification and export performance by destination country. Bulletin of Economic Research 71: 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dennis, Allen, and Shepherd Ben. 2011. Trade Facilitation and Export Diversification. The World Economy 34: 101–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Caro, Paolo, and Fratesi Ugo. 2018. Regional determinants of economic resilience. Annals of Regional Science 60: 235–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Driscoll, John C., and Kraay Aart C. 1998. Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimation with Spatially Dependent Panel Data. Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 549–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, Romain, and Furceri David. 2018. The Effects of Labor and Product Market Reforms: The Role of Macroeconomic Conditions and Policies. IMF Economic Review 66: 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichengreen, Barry, and Leblang David. 2003. Capital Account Liberalization and Growth: Was Mr. Mahathir Right? International Journal of Finance and Economics 8: 205–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esfahani, Hadi Salehi, and Ramirez María Teresa. 2003. Institutions, Infrastructure, and Economic Growth. Journal of Development Economics 70: 443–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenett, Simon, Fiorini Matteo, Fritz Johannes, Hoekman Bernard, Lukaszuk Piotr, Rocha Nadia, Ruta Michele, Santi Filippo, and Shingal Anirudh. 2022. Trade Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. Evidence from a New Data Set. The World Economy 45: 342–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, Gianrico, and Roshelle W. Plutowski. 2021. Innovation Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspective and Controversy 95: 1574–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feindouno, Sosso, and Goujon Michaël. 2016. The Retrospective Economic Vulnerability Index, 2015 Update. Working Paper n°147. Clermont-Ferrand: Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement International (FERDI). [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Ling, and Lin Ching-Yi. 2013. Financial shocks and exports. International Review of Economics & Finance 26: 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, Michael, and Ruhwedel Ralf. 2001. Export variety and export performance: Empirical evidence from East Asia. Journal of Asian Economics 12: 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, Michael, and Ruhwedel Ralf. 2002. Export variety and export performance: Empirical evidence for the OECD Countries. Review of World Economics 138: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassebner, Martin, Keck Alexander, and The Robert. 2010. Shaken, not stirred: The impact of disasters on international trade. Review of International Economics 18: 351–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Atish, and Ostry Jonathan. 1994. Export Instability and the External Balance in Developing Countries. IMF Staff Papers 41: 214–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019a. Has the WTO’s Aid for Trade Initiative Delivered on Its Promise of Greater Mobilization of Development Aid in Favor of the Trade Sector in Developing Countries? International Trade Journal 33: 519–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2019b. Aid for Trade and Recipient-Countries’ Export Structure: Does Trade Policy Liberalization Matter? Arthaniti: Journal of Economic Theory and Practice 18: 56–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2020. Aid for Trade flows and Real Exchange Rate Volatility in Recipient-Countries. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy 13: 2250001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021a. Effect of Productive Capacities on Economic Complexity: Do Aid for Trade flows Matter? Journal of Economic Integration 36: 626–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021b. Productive Capacities, Economic Growth and Economic Growth Volatility in Developing Countries: Does Structural Economic Vulnerability Matter? Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy. Available online: https://doi/10.1142/S1793993325500012 (accessed on 10 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021c. Effect of Productive Capacities on Economic Resilience in Developing Countries. Preprints Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2021d. Effect of Development Aid on Productive Capacities. Kiel and Hamburg: ZBW—Leibniz Information Centre for Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Gradeva, Katerina, and Martínez-Zarzoso Inmaculada. 2015. Are Trade Preferences more Effective than Aid in Supporting Exports? Evidence from the ‘Everything But Arms’ Preference Scheme. The World Economy 39: 1146–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Gene M., and Helpman Elhanan. 2015. Globalization and growth. American Economic Review 105: 100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumont, Patrick. 2009. An Economic Vulnerability Index: Its Design and Use for International Development Policy. Oxford Development Studies 37: 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guillaumont, Patrick. 2017. Vulnerability and Resilience: A Conceptual Framework Applied to Three Asian Countries—Bhutan, Maldives, and Nepal. ADB South Asia Working Paper No. 53. Mandaluyong: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, Mona, Lim Jamus Jerome, Pancaro Cosimo, and Saborowski Christian. 2013. Trade openness reduces growth volatility when countries are well diversified. Canadian Journal of Economics 46: 765–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, Stephane. 2014. Economic Resilience—Definition and Measurement. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS6852. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, Kazunobu, and Mukunoki Hiroshi. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on international trade: Evidence from the first shock. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 60: 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, Rana, and Zaki Chahir. 2021. Trade facilitation and firms exports: Evidence from customs data. International Review of Economics & Finance 75: 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Herrendorf, Berthold, Richard Rogerson, and Ákos Valentinyi. 2014. Chapter 6—Growth and Structural Transformation. In Handbook of Economic Growth. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 2, pp. 855–941. [Google Scholar]

- Hundt, Christian, and Holtermann Linus. 2020. The role of national settings in the economic resilience of regions—Evidence from recessionary shocks in Europe from 1990 to 2014. Growth and Change 51: 180–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, Sangyeon, and Im Hyejoon. 2013. Financial shocks and trade finance: Evidence from Korea. Economics Letters 120: 104–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. 2021. World Economic Outlook: Managing Divergent Recoveries. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jolles, Maya, Meyermans Eric, and Vasicek Borek. 2018. Determinants of Economic Resilience in the Euro Area: An empirical Assessment of Policy Levers. Quarterly Report on the Euro Area (QREA). Brussels: Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission, vol. 17, pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Jiandong, Yi Wu, and Zeng Li. 2010. The Impact of Trade Liberalization on the Trade Balance in Developing Countries. IMF Staff Papers 57: 427–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, Farid, Birregah Babiga, and Châtelet Eric. 2014. The Impact of Natural Disasters on Critical Infrastructures: A Domino Effect-based Study. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 11: 217–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnan, Cynthia, and Townsend Robert. 2012. Kinship and financial networks, formal financial access, and risk reduction. The American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 102: 289–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kramarz, Francis, Martin Julien, and Mejean Isabelle. 2020. Volatility in the small and in the large: The lack of diversification in international trade. Journal of International Economics 122: 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Helga. 2012. Exports from a remote developed region: Analysed by an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of the gravity model. The World Economy 35: 953–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chunding, and Lin Xin. 2021. COVID-19 and trade: Simulated asymmetric loss. Journal of Asian Economics 75: 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuhong, and Zobel Christopher W. 2020. Exploring supply chain network resilience in the presence of the ripple effect. International Journal of Production Economics 228: 107693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, Daniela, Lo Turco Alessia, and Gallegati Mauro. 2016. Does product complexity matter for firms’ output volatility? Journal of Development Economics 121: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markusen, James R., and Venables Anthony J. 1999. Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. European Economic Review 43: 335–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, Ron, and Sunley Peter. 2015. On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography 15: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marto, Ricardo, Papageorgiou Chris, and Klyuev Vladimir. 2018. Building resilience to natural disasters: An application to small developing states. Journal of Development Economics 135: 574–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayunga, Joseph. 2007. Understanding and Applying the Concept of Community Disaster Resilience: A Capital-Based Approach’, Draft Working Paper Prepared for the Summer Academy, Megacities as Hotspots of Risk: Social Vulnerability and Resilience Building. College Station: Texas A&M University. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, Mösle Saskia, and Windisch Michael. 2020. Lessons from Past Disruptions to Global Value Chains. UNIDO Industrial Analytics Platform. Available online: https://iap.unido.org/articles/lessons-past-disruptions-global-value-chains (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Miller, Terry, Kim B. Anthony, James M. Roberts, and Tyrrell Patrick. 2021. 2021 Index of Economic Freedom. Washington, DC: Institute for Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation, Available online: https://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2021/book/index_2021.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Miranda-Pinto, Jorge. 2021. Production network structure, service share, and aggregate volatility. Review of Economic Dynamics 39: 146–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroudot, Sébastien. 2020. Reshaping the policy debate on the implications of COVID-19 for global supply chains. Journal of International Business Policy 3: 430–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, Pierluigi. 2011. Trade Openness and Developing Countries’ Vulnerability: Concepts, Misconceptions, and Directions for Research. World Development 39: 1489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munch, Jakob Roland, and Skaksen Jan Rose. 2008. Human capital and wages in exporting firms. Journal of International Economics 75: 363–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Board of Trade Sweden. 2020. Improving Economic Resilience through Trade—Should We Rely on Our Own Supply? Stockholm: The National Board of Trade Sweden, 51p, Available online: https://www.wita.org/atp-research/improving-economic-resilience/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Nordhagen, Stella, Igbeka Uduak, Rowlands Hannah, Shine Ritta Sabbas, Heneghan Emily, and Tench Jonathan. 2021. COVID-19 and small enterprises in the food supply chain: Early impacts and implications for longer-term food system resilience in low-and middle-income countries. World Development 141: 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, Maurice. 1994. Risk-taking, global diversification and growth. American Economic Review 84: 1310–29. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2017. OECD G20 Policy Paper on Economic Resilience and Structural Policies. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2020. Development Co-operation Report 2020: Learning from Crises, Building Resilience. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021. Fostering Economic Resilience in a World of Open and Integrated Markets—Risks, Vulnerabilities and Areas for Policy Action. UK Presidency of the G7. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Chang Hoon, and Reuveny Rafael. 2010. Climatic natural disasters, political risk, and international trade. Global Environmental Change 20: 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarreaga, Marcelo. 2016. Trade, Infrastructure and Development. FERDI Working Paper Development Policies n° 177. Clermont-Ferrand: Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Développement International (FERDI). [Google Scholar]

- Osakwe, Patrick, Santos-Paulino Amelia, and Dogan Berna. 2018. Trade dependence, liberalization, and exports diversification in developing countries. Journal of African Trade 5: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, Jayash, and Ryu Hanbyul. 2018. Natural disasters and human capital: The case of Nepal’s earthquake. World Development 111: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunov, Caroline, and Planes-Satorra Sandra. 2021. Science, Technology and Innovation in the Time of COVID-19. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 99. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Paunov Caroline, Rollo Valentina. 2016. Has the internet fostered inclusive innovation in the Developing World? World Development 78: 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, Adam, Wei Dan, and Paul Donald. 2018. Economic consequences of and resilience to a disruption of petroleum trade: The role of seaports in U.S. energy security. Energy Policy 115: 584–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Aida Caldera, and Röhn Oliver. 2016. How Do Policies Influence GDP Tail Risks? OECD Economics Department Working Papers ECO/WKP (2016) 63. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saltarelli, Francesco, Cimini Valeria, Tacchella Andrea, Zaccaria Andrea, and Cristelli Matthieu. 2020. Is Export a Probe for Domestic Production? Frontiers in Physics 8: 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Paulino, Amelia U. 2007. Aid and Trade Sustainability under Liberalisation in Least Developed Countries. The World Economy 30: 972–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmukler, Sergio L., and Vesperoni Esteban. 2006. Financial Globalization and Debt Maturity in Emerging Economies. Journal of Development Economics 79: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, Dauda, and Maciej Drozd. 2020. Barriers to Competition in Product Market Regulation: New Insights on Emerging Market and Developing Economies. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Sepehrdoust, Hamid, Davarikish Razieh, and Setarehie Maryam. 2019. The knowledge-based products and economic complexity in developing countries. Heliyon 5: e02979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Somville, Vincent, and Vandewalle Lore. 2019. Access to Banking, Savings and Consumption Smoothing in Rural India. Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Working Paper No. HEIDWP09-2019. Geneva: Graduatie Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Sondermann, David. 2018. Towards more resilient economies: The role of well-functioning economic structures. Journal of Policy Modeling 40: 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spatareanu, Mariana, Manole Vlad, and Kabiri Ali. 2018. Exports and bank shocks: Evidence from matched firm-bank data. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 47: 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulz, René. 1999. Globalization, Corporate Finance and the Cost of Capital. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 12: 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Hesar, Farhad, Sarker Tapan, Yoshino Naoyuki, Mortha Aline, and Vo Xuan Vinh. 2021. Quality infrastructure and natural disaster resiliency: A panel analysis of Asia and the Pacific. Economic Analysis and Policy 60: 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, Justice A., and Wünscher Tobias. 2017. Enhancing resilience to climate shocks through farmer innovation: Evidence from northern Ghana. Regional Environmental Change 17: 1505–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. 2006. The Least Developed Countries Report 2006: Developing Productive Capacities. Sales No. E.06.II.D.9. New York and Geneva: United Nations Publication. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. 2020. The Least Developed Countries Report 2020: Productive Capacities for the New Decade. Sales No. E.21.II.D.2. New York and Geneva: United Nations publication. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2016. Global Sustainable Development Report 2016. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Vannoorenberghe, Gonzague, Wang Zheng, and Yu Zhihong. 2016. Volatility and diversification of exports: Firm-level theory and evidence. European Economic Review 89: 216–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vijil, Mariana, and Wagner Laurent. 2012. Does Aid for Trade Enhance Export Performance? Investigating the Infrastructure Channel. The World Economy 37: 838–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Rong, Tan Junlan, and Yao Shuangliang. 2021. Are natural resources a blessing or a curse for economic development? The importance of energy innovations. Resources Policy 72: 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO (World Trade Organization). 2005. Ministerial Declaration on Doha Work Programme’, WT/MIN(05)/DEC. Paper presented at 18 December 2005 at the Sixth Session of Trade Ministers Conference, Ministerial Conference, Hong Kong, China, December 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Xiaoping, and Khazin Bassam Peter. 2020. Patent-Related Actions Taken in WTO Members in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2020-12. Geneva: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zeev, Nadav Ben, and Ifergane Tomer. 2021. Firing restrictions and economic resilience: Protect and survive? Review of Economic Dynamics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | PCI | PCI | PCI | PCI | PCI | PCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| PCIt−1 | 1.112 *** (0.0423) | 1.036 *** (0.0449) | 1.121 *** (0.0426) | 1.065 *** (0.0474) | 1.040 *** (0.0495) | 1.048 *** (0.0425) |

| PCIt−2 | −0.188 *** (0.0345) | −0.188 *** (0.0377) | −0.187 *** (0.0348) | −0.213 *** (0.0407) | −0.173 *** (0.0426) | −0.156 *** (0.0397) |

| Log(ODA) | 0.241 *** (0.0556) | |||||

| Log(AfTTOT) | 0.239 *** (0.0271) | |||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT) | 0.216 *** (0.0631) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 0.161 *** (0.0276) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 0.252 *** (0.0439) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 0.0956 *** (0.0234) | |||||

| OPEN | 0.104 (0.212) | 0.256 (0.172) | 0.0712 (0.204) | 0.204 (0.200) | 0.101 (0.198) | 0.240 (0.189) |

| TOTREV | 0.360 (0.539) | 0.0516 (0.527) | 0.732 (0.563) | 0.0496 (0.515) | 1.008 * (0.588) | 0.0336 (0.716) |

| FINPOL | 0.972 *** (0.158) | 0.996 *** (0.153) | 0.940 *** (0.170) | 0.866 *** (0.159) | 1.383 *** (0.151) | 1.047 *** (0.150) |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.402 *** (0.0945) | 0.626 *** (0.110) | 0.367 *** (0.0933) | 0.610 *** (0.106) | 0.538 *** (0.0776) | 0.431 *** (0.0832) |

| Constant | −5.909 *** (1.413) | −5.354 *** (0.781) | −5.374 *** (1.579) | −3.704 *** (0.752) | −5.357 *** (0.967) | −1.906 *** (0.472) |

| Observations-Countries | 321-87 | 321-87 | 321-87 | 321-87 | 321-87 | 319-87 |

| Number of Instruments | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0012 | 0.0011 | 0.0021 | 0.0054 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.9613 | 0.9189 | 0.9826 | 0.9652 | 0.9530 | 0.8480 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.3518 | 0.6664 | 0.3316 | 0.5059 | 0.7017 | 0.6199 |

| Variables | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(ODA)t−1 | 0.0974 *** (0.0351) | |||||

| Log(AfTTOT)t−1 | 0.0433 *** (0.00253) | |||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT)t−1 | 0.0814 ** (0.0377) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA)t−1 | 0.0201 *** (0.00629) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD)t−1 | 0.0264 ** (0.0106) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL)t−1 | 0.0235 *** (0.00324) | |||||

| Log(GDPC)t−1 | 0.777 *** (0.0255) | 0.714 *** (0.0280) | 0.817 *** (0.0301) | 0.745 *** (0.0306) | 0.760 *** (0.0269) | 0.786 *** (0.0391) |

| Log(TP)t−1 | 0.182 *** (0.0514) | 0.195 *** (0.0569) | 0.210 *** (0.0475) | 0.207 *** (0.0674) | 0.230 *** (0.0534) | 0.179 *** (0.0588) |

| FINPOLt−1 | −0.368 *** (0.107) | −0.396 *** (0.0900) | −0.306 *** (0.102) | −0.320 *** (0.0958) | −0.330 *** (0.0923) | −0.360 *** (0.115) |

| [FINPOLt−1]2 | 0.381 *** (0.109) | 0.423 *** (0.111) | 0.326 *** (0.114) | 0.371 *** (0.128) | 0.367 *** (0.0991) | 0.347 ** (0.137) |

| Constant | −8.595 *** (0.742) | −7.004 *** (0.326) | −8.683 *** (0.932) | −6.869 *** (0.357) | −7.187 *** (0.359) | −7.012 *** (0.359) |

| Observations-Countries | 427-93 | 426-93 | 426-93 | 426-93 | 426-93 | 420-93 |

| Within R2 | 0.2588 | 0.2493 | 0.2538 | 0.2455 | 0.2438 | 0.2670 |

| Variables | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| RESILt−1 | 1.094 *** (0.0558) | 1.046 *** (0.0535) | 1.091 *** (0.0550) | 0.999 *** (0.0484) | 1.094 *** (0.0574) | 1.057 *** (0.0504) |

| RESILt−2 | −0.334 *** (0.0396) | −0.260 *** (0.0319) | −0.335 *** (0.0395) | −0.246 *** (0.0325) | −0.276 *** (0.0360) | −0.349 *** (0.0369) |

| Log(ODA) | 0.0999 *** (0.0175) | |||||

| Log(AfTTOT) | 0.0736 *** (0.0103) | |||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT) | 0.126 *** (0.0201) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 0.0542 *** (0.00695) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 0.0830 *** (0.00925) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 0.0265 *** (0.00766) | |||||

| Log(TP) | −0.267 (0.183) | −0.366 ** (0.152) | −0.354 * (0.191) | −0.253 ** (0.124) | −0.524 *** (0.152) | −0.110 (0.131) |

| FINPOL | −0.557 *** (0.182) | −0.843 *** (0.170) | −0.509 *** (0.185) | −0.700 *** (0.156) | −0.652 *** (0.173) | −0.426 ** (0.212) |

| [FINPOL]2 | 0.496 *** (0.178) | 0.864 *** (0.157) | 0.444 ** (0.180) | 0.730 *** (0.147) | 0.568 *** (0.179) | 0.442 ** (0.209) |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.0224 (0.0233) | −0.000571 (0.0176) | 0.0449 * (0.0244) | 0.00205 (0.0143) | 0.00947 (0.0170) | −0.00980 (0.0157) |

| Constant | −0.876 * (0.501) | 0.310 (0.520) | −1.168 ** (0.544) | 0.264 (0.446) | 0.886 (0.559) | 0.198 (0.492) |

| Observations-Countries | 327-93 | 327-93 | 327-93 | 327-93 | 327-93 | 325-93 |

| Number of Instruments | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0007 | 0.0049 | 0.0005 | 0.0047 | 0.0014 | 0.0028 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.3339 | 0.6375 | 0.2480 | 0.6101 | 0.3982 | 0.5768 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.6788 | 0.8576 | 0.8469 | 0.6853 | 0.9189 | 0.7071 |

| Variables | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| RESILt−1 | 1.015 *** (0.0450) | 1.032 *** (0.0450) | 0.992 *** (0.0403) | 0.883 *** | 0.994 *** | 0.883 *** | 0.924 *** | 1.023 *** |

| RESILt−2 | −0.326 *** (0.0318) | −0.348 *** (0.0341) | −0.344 *** (0.0291) | −0.234 *** (0.0238) | −0.347 *** (0.0268) | −0.231 *** (0.0249) | −0.252 *** (0.0275) | −0.342 *** (0.0284) |

| Log(ODA) | 0.119 *** (0.0193) | 1.133 *** (0.182) | ||||||

| Log(PCI) | 0.270 ** (0.129) | −0.525 *** (0.160) | 6.144 *** (1.073) | 4.833 *** (0.904) | 4.700 *** (1.144) | 3.272 *** (0.835) | 3.473 *** (0.658) | 0.118 (0.294) |

| [Log(ODA)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.322 *** (0.0544) | |||||||

| Log(AfTTOT) | 1.107 *** (0.157) | |||||||

| [Log(AfTTOT)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.310 *** (0.0480) | |||||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT) | 0.890 *** (0.189) | |||||||

| [Log(NonAfTTOT)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.248 *** (0.0574) | |||||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 0.780 *** (0.157) | |||||||

| [Log(AfTINFRA)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.218 *** (0.0469) | |||||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 0.839 *** (0.122) | |||||||

| [Log(AfTPROD)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.236*** (0.0367) | |||||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 0.0816 (0.0671) | |||||||

| [Log(AfTPOL)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.0178 (0.0204) | |||||||

| Log(GDPC) | −0.0414 * (0.0239) | 0.114 *** (0.0307) | 0.0820 *** (0.0201) | 0.130 *** (0.0248) | 0.0730 *** (0.0179) | 0.0762 *** (0.0226) | 0.100 *** (0.0214) | 0.0154 (0.0156) |

| Log(TP) | −0.0424 (0.109) | −0.0635 (0.127) | −0.0636 (0.0980) | −0.0722 (0.0774) | −0.0282 (0.0903) | −0.107 (0.0786) | −0.0811 (0.0980) | 0.0314 (0.0808) |

| FINPOL | −0.574 *** (0.187) | −0.147 (0.200) | −0.643 *** (0.153) | −0.692 *** (0.150) | −0.665 *** (0.152) | −0.584 *** (0.134) | −0.600 *** (0.165) | −0.511 *** (0.173) |

| [FINPOL]2 | 0.590 *** (0.169) | 0.193 (0.184) | 0.615 *** (0.146) | 0.603 *** (0.143) | 0.633 *** (0.148) | 0.563 *** (0.122) | 0.530 *** (0.155) | 0.524 *** (0.149) |

| Constant | −0.331 (0.383) | −1.335*** (0.413) | −22.05 *** (3.547) | −18.02 *** (2.864) | −17.26 *** (3.695) | −11.98 *** (2.737) | −12.90 *** (2.092) | −0.825 (1.025) |

| Turning point of “PCI” | n.a. | n.a. | Exponential (1.133/0.322) = 33.74 | Exponential (1.107/0.310) = 35.55 | Exponential (0.890/0.248) = 36.19 | Exponential (0.780/0.218) = 35.8 | Exponential (0.839/0.236) = 35 | n.a. |

| Observations-Countries | 328-93 | 325-93 | 325-93 | 325-93 | 325-93 | 325-93 | 325-93 | 323-93 |

| Number of Instruments | 65 | 58 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0029 | 0.0011 | 0.0015 | 0.0055 | 0.0014 | 0.0065 | 0.0024 | 0.0032 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.5261 | 0.1924 | 0.4515 | 0.4872 | 0.3846 | 0.5351 | 0.2909 | 0.5062 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.1259 | 0.6573 | 0.2312 | 0.4664 | 0.2354 | 0.6645 | 0.2999 | 0.3264 |

| Variables | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| RESILt−1 | 0.861 *** (0.0559) | 0.761 *** (0.0553) | 0.854 *** (0.0581) | 0.773 *** (0.0535) | 0.756 *** (0.0534) | 0.816 *** (0.0591) |

| RESILt−2 | −0.273 *** (0.0419) | −0.182 *** (0.0350) | −0.279 *** (0.0434) | −0.179 *** (0.0357) | −0.198 *** (0.0359) | −0.283 *** (0.0373) |

| Log(ODA) | 0.0844 *** (0.0178) | |||||

| Log(AfTTOT) | 0.0742 *** (0.00921) | |||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT) | 0.107 *** (0.0221) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 0.0552 *** (0.00620) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 0.0736 *** (0.00832) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 0.0358 *** (0.00805) | |||||

| Log(TP) | −0.122 (0.184) | −0.261 * (0.149) | −0.239 (0.190) | −0.212 * (0.118) | −0.374 *** (0.138) | −0.149 (0.129) |

| FINPOL | −0.471 ** (0.188) | −0.913 *** (0.153) | −0.411 ** (0.196) | −0.622 *** (0.143) | −0.794 *** (0.148) | −0.610 *** (0.186) |

| [FINPOL]2 | 0.442 ** (0.176) | 0.922 *** (0.144) | 0.369 ** (0.181) | 0.652 *** (0.135) | 0.754 *** (0.157) | 0.599 *** (0.186) |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.0210 (0.0238) | 0.0122 (0.0197) | 0.0516 ** (0.0248) | 0.0102 (0.0153) | 0.0252 (0.0172) | 0.00747 (0.0158) |

| Constant | −1.285 *** (0.472) | −0.154 (0.490) | −1.457 *** (0.476) | −0.0738 (0.403) | 0.209 (0.491) | 0.125 (0.483) |

| Observations-Countries | 312-89 | 312-89 | 312-89 | 312-89 | 312-89 | 310-89 |

| Number of Instruments | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0013 | 0.0093 | 0.0009 | 0.0076 | 0.0043 | 0.0050 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.6923 | 0.7955 | 0.5684 | 0.8534 | 0.9597 | 0.5893 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.6074 | 0.6293 | 0.8138 | 0.5669 | 0.4975 | 0.5671 |

| Variables | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL | RESIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| RESILt−1 | 0.824 *** (0.0381) | 0.687 *** (0.0299) | 0.820 *** (0.0360) | 0.697 *** (0.0338) | 0.718 *** (0.0430) | 0.811 *** (0.0392) |

| RESILt−2 | −0.301 *** (0.0316) | −0.195 *** (0.0247) | −0.312 *** (0.0282) | −0.176 *** (0.0266) | −0.218 *** (0.0278) | −0.274 *** (0.0256) |

| Log(ODA) | 0.974 *** (0.147) | |||||

| [Log(ODA)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.275 *** (0.0444) | |||||

| Log(AfTTOT) | 0.962 *** (0.159) | |||||

| [Log(AfTTOT)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.266 *** (0.0487) | |||||

| Log(NonAfTTOT) | 0.736 *** (0.153) | |||||

| [Log(NonAfTTOT)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.202 *** (0.0464) | |||||

| Log(AfTINFRA) | 0.775 *** (0.131) | |||||

| [Log(AfTINFRA)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.216 *** (0.0388) | |||||

| Log(AfTPROD) | 0.926 *** (0.122) | |||||

| [Log(AfTPROD)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.263 *** (0.0361) | |||||

| Log(AfTPOL) | 0.191 *** (0.0383) | |||||

| [Log(AfTPOL)] × [Log(PCI)] | −0.0516 *** (0.0125) | |||||

| Log(PCI) | 5.380 *** (0.886) | 4.152 *** (0.922) | 3.926 *** (0.932) | 3.384 *** (0.686) | 4.094 *** (0.629) | 0.646 *** (0.194) |

| Log(TP) | −0.112 (0.0854) | −0.107 (0.0796) | −0.0589 (0.0842) | −0.194 ** (0.0786) | −0.117 (0.0961) | 0.0453 (0.0895) |

| FINPOL | −0.786 *** (0.132) | −0.666 *** (0.135) | −0.772 *** (0.126) | −0.562 *** (0.118) | −0.599 *** (0.144) | −0.428 *** (0.120) |

| [FINPOL]2 | 0.736 *** (0.128) | 0.587 *** (0.130) | 0.702 *** (0.125) | 0.567 *** (0.103) | 0.528 *** (0.135) | 0.408 *** (0.112) |

| Log(GDPC) | 0.0759 *** (0.0192) | 0.132 *** (0.0233) | 0.0692 *** (0.0173) | 0.0705 *** (0.0171) | 0.0974 *** (0.0201) | 0.00759 (0.0121) |

| Constant | −19.04 *** (2.821) | −15.65 *** (2.890) | −14.57 *** (2.937) | −11.88 *** (2.195) | −14.79 *** (2.004) | −2.548 *** (0.677) |

| Turning point of “PCI” | Exponential (0.974/0.275) = 34.53 | Exponential (0.962/0.266) = 37.21 | Exponential (0.736/0.202) = 38.23 | Exponential (0.775/0.216) = 36.16 | Exponential (0.926/0.263) = 33.82 | Exponential (0.191/0.0516) = 40.5 |

| Observations-Countries | 310-89 | 310-89 | 310-89 | 310-89 | 310-89 | 308-89 |

| Number of Instruments | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 |

| AR1 (p-Value) | 0.0018 | 0.0085 | 0.0015 | 0.0084 | 0.0039 | 0.0056 |

| AR2 (p-Value) | 0.9335 | 0.9664 | 0.9663 | 0.9046 | 0.8029 | 0.9186 |

| OID (p-Value) | 0.2417 | 0.4510 | 0.2234 | 0.5310 | 0.3693 | 0.2752 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gnangnon, S.K. Development Aid and Export Resilience in Developing Countries: A Reference to Aid for Trade. Economies 2022, 10, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070161

Gnangnon SK. Development Aid and Export Resilience in Developing Countries: A Reference to Aid for Trade. Economies. 2022; 10(7):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070161

Chicago/Turabian StyleGnangnon, Sèna Kimm. 2022. "Development Aid and Export Resilience in Developing Countries: A Reference to Aid for Trade" Economies 10, no. 7: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070161

APA StyleGnangnon, S. K. (2022). Development Aid and Export Resilience in Developing Countries: A Reference to Aid for Trade. Economies, 10(7), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070161