Financing Startups and Impact Investing: Evidence Across MENA Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What factors drive the financial success of impact-investing startups compared with conventional startups in MENA?

- (2)

- Do the determinants of success differ structurally between these two groups?

- (3)

- What challenges characterize startups engaged in impact investment relative to conventional firms.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Emergence and Definition of Impact Investment

2.2. Performance Debate: The Mission–Finance Trade-Off

2.3. Measuring Startup Financial Success: A Signaling Perspective

3. Methods

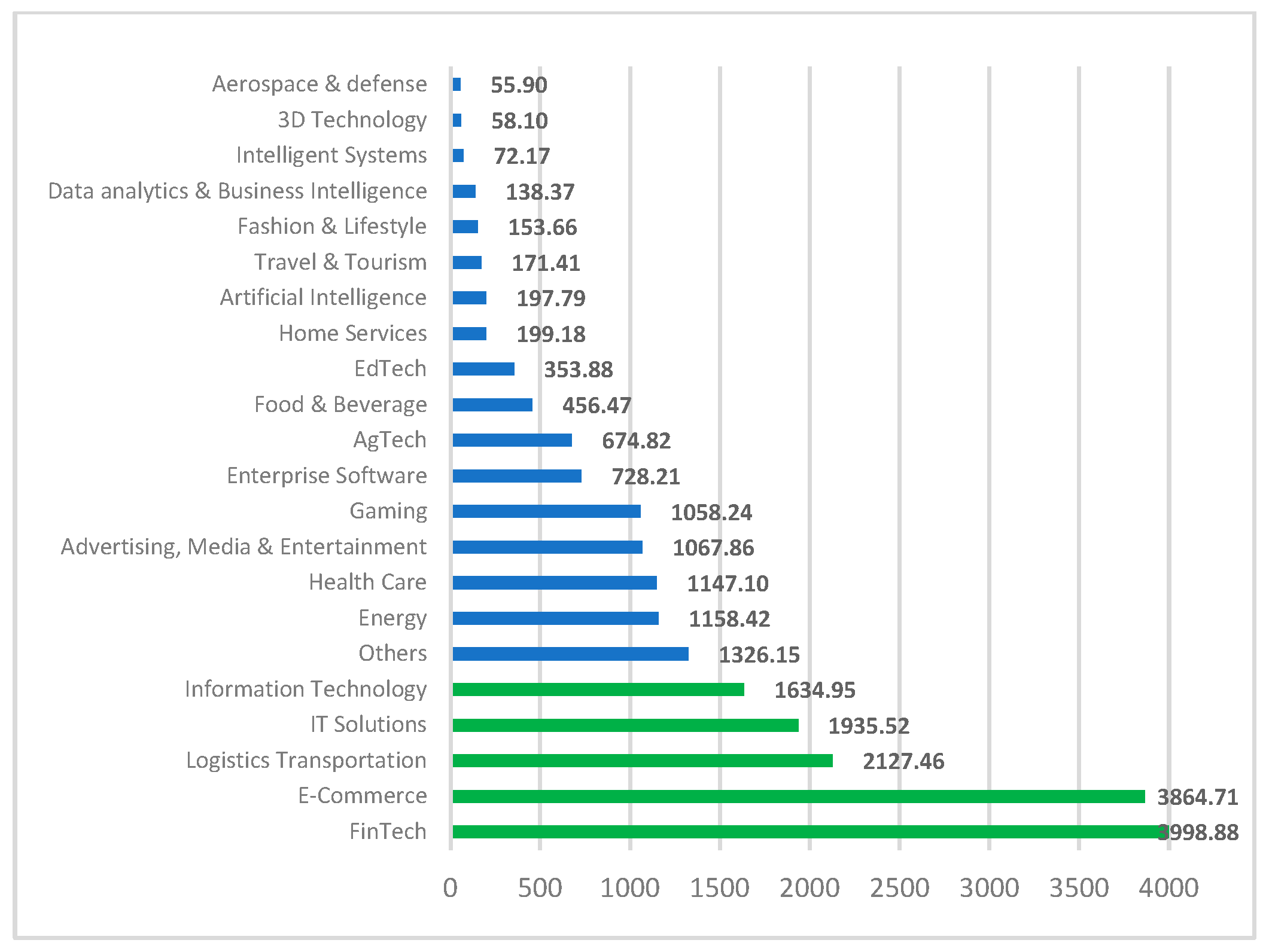

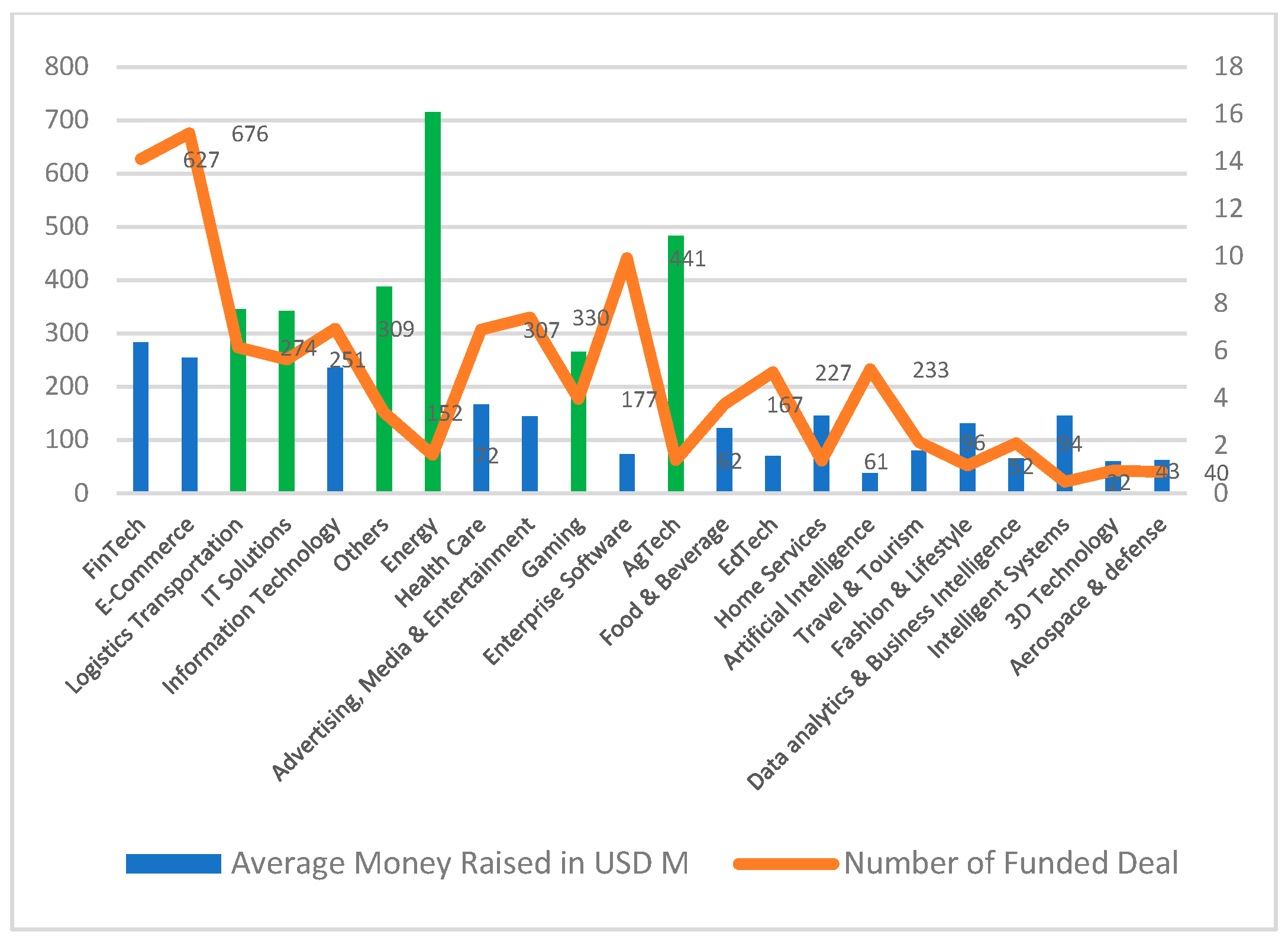

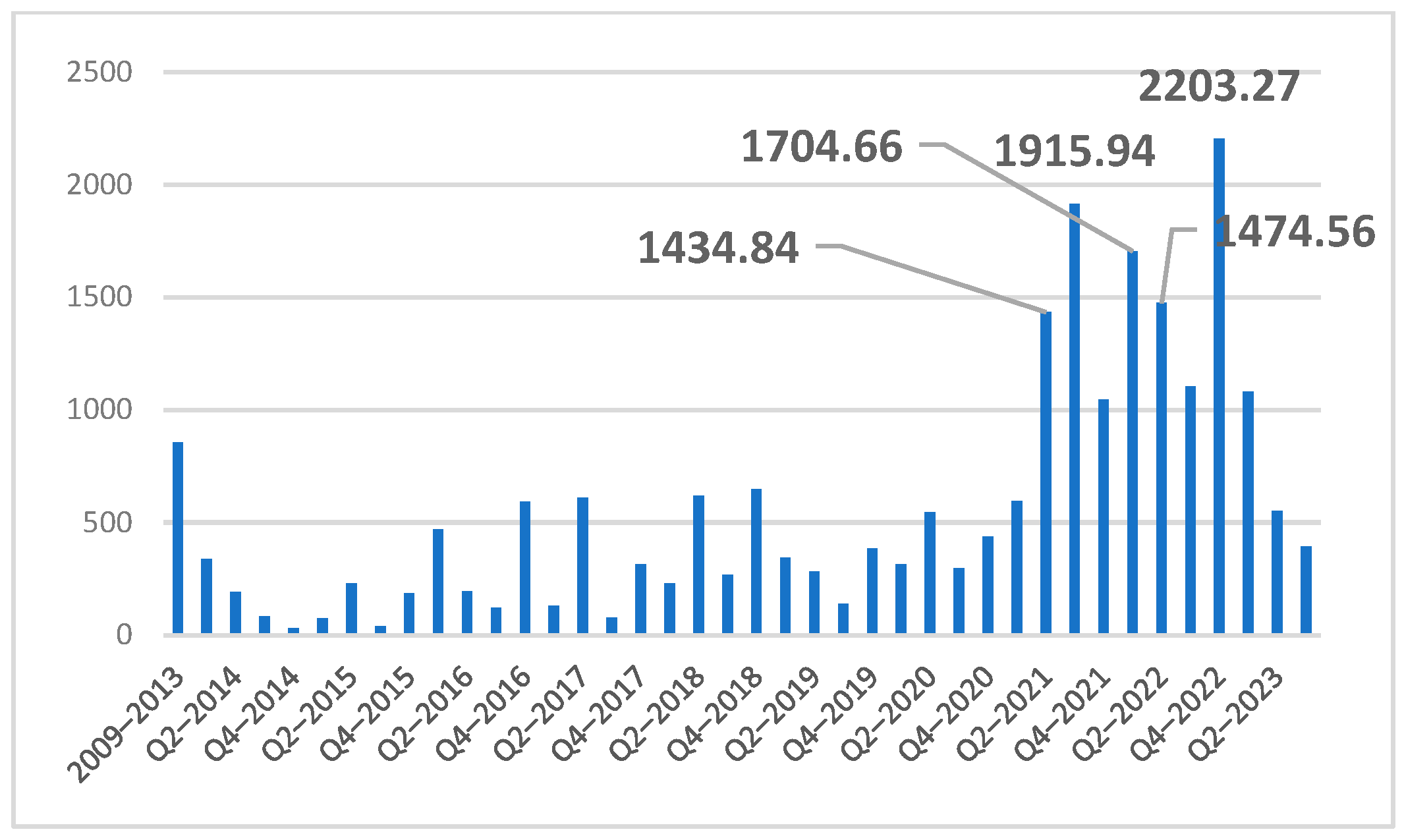

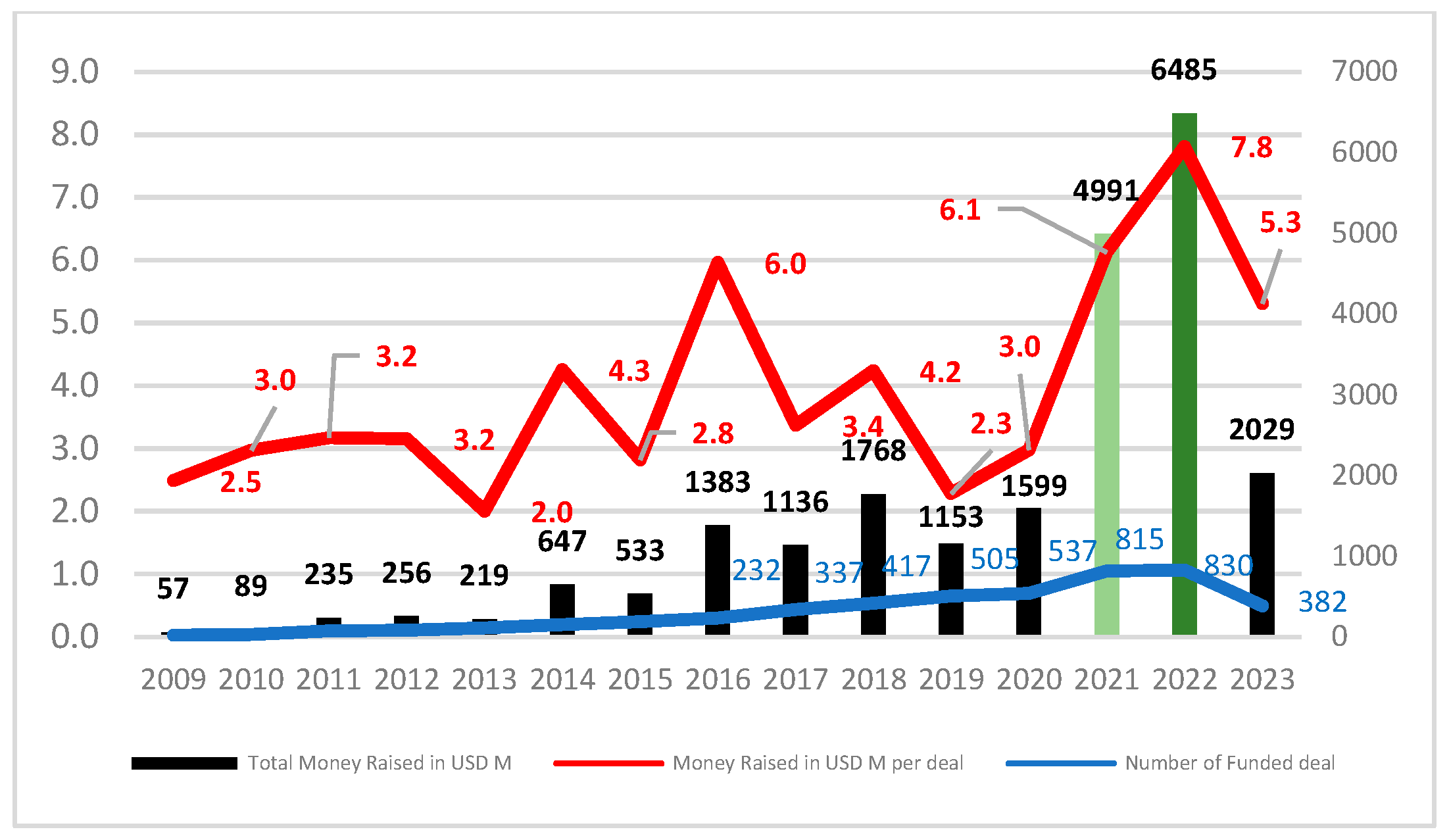

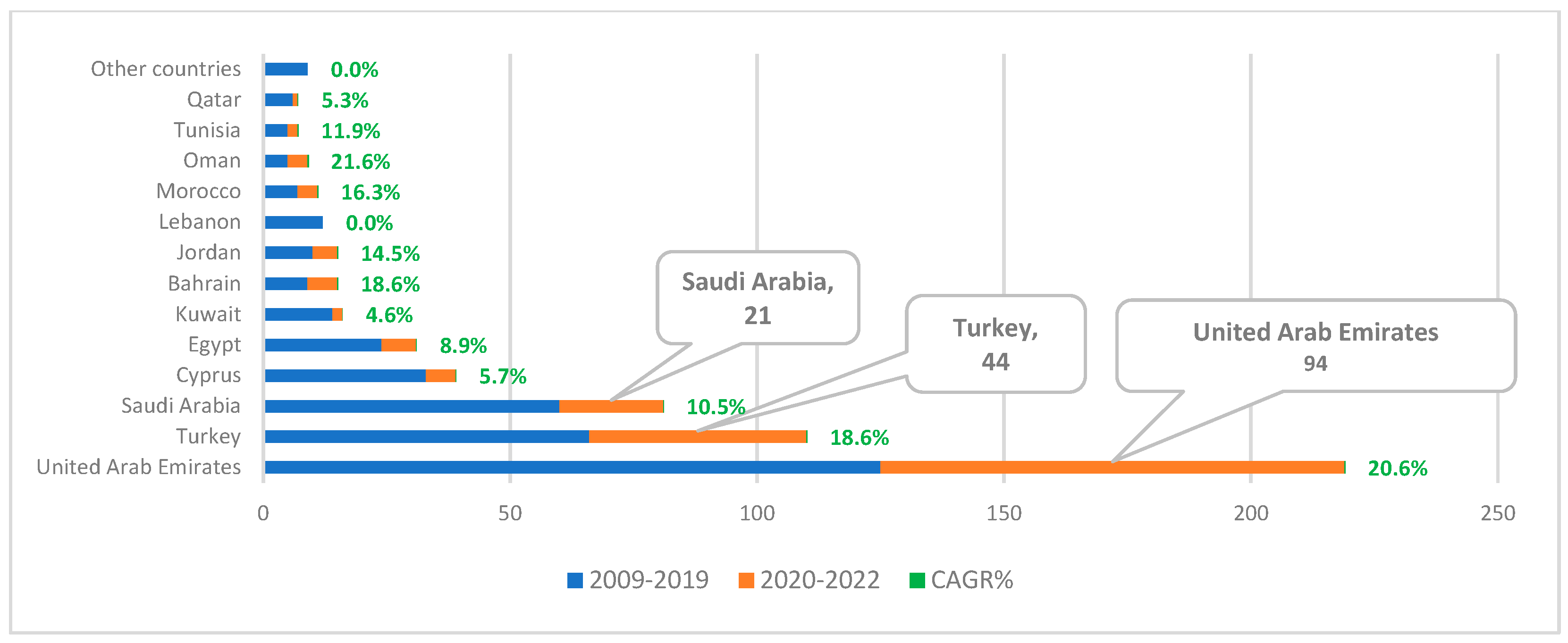

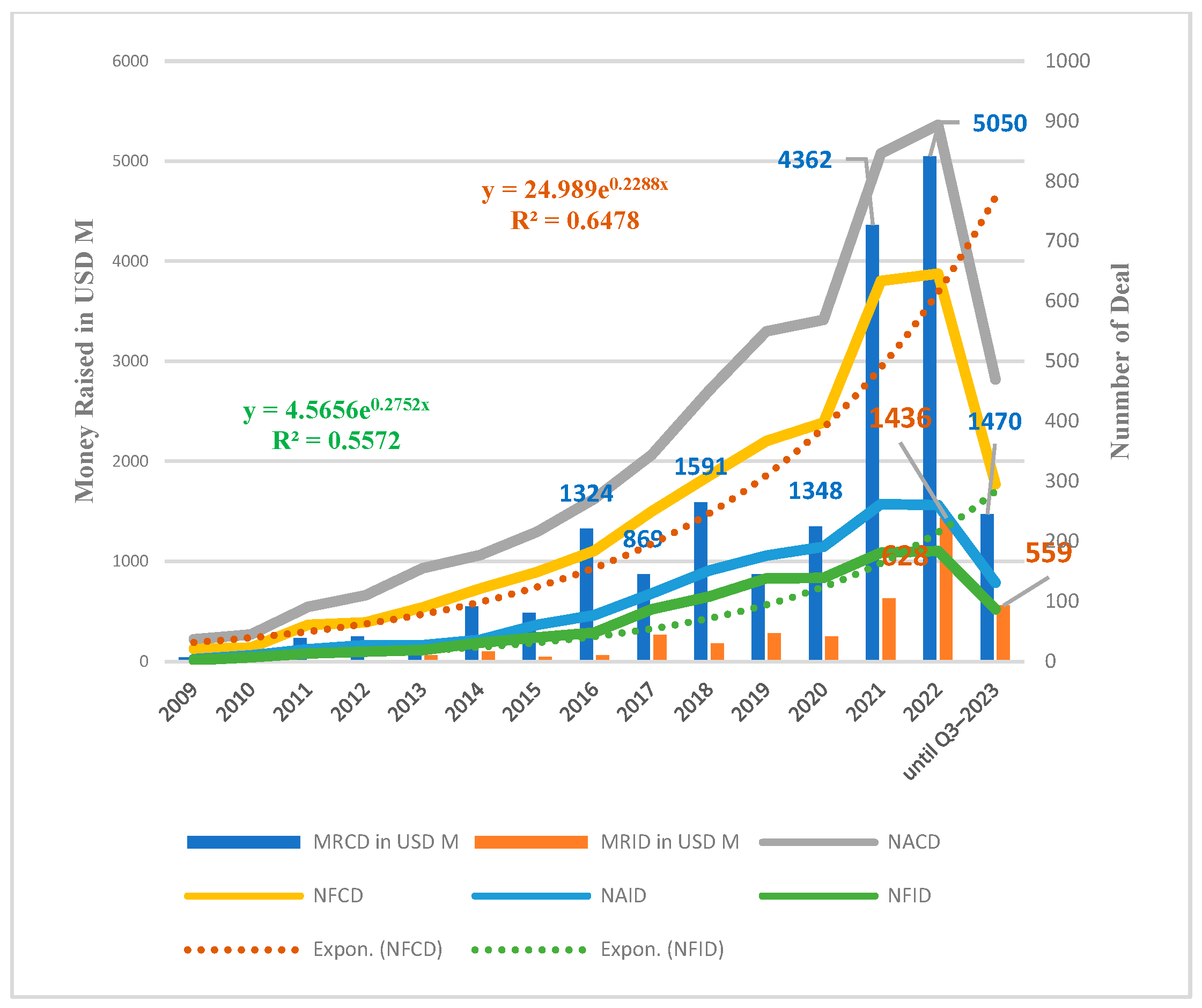

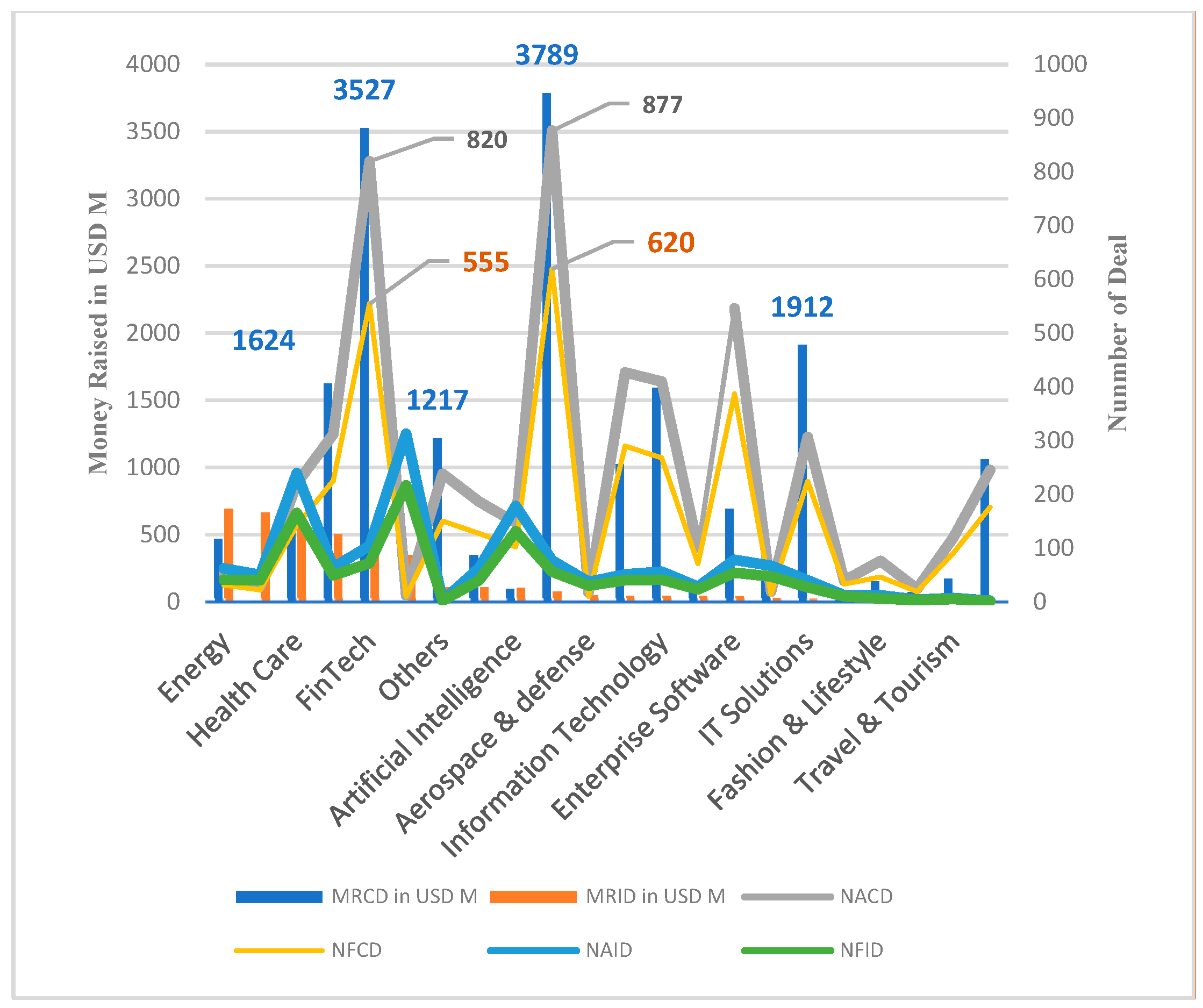

3.1. Sample, Data, and Landscape of Financing the MENA Ecosystem

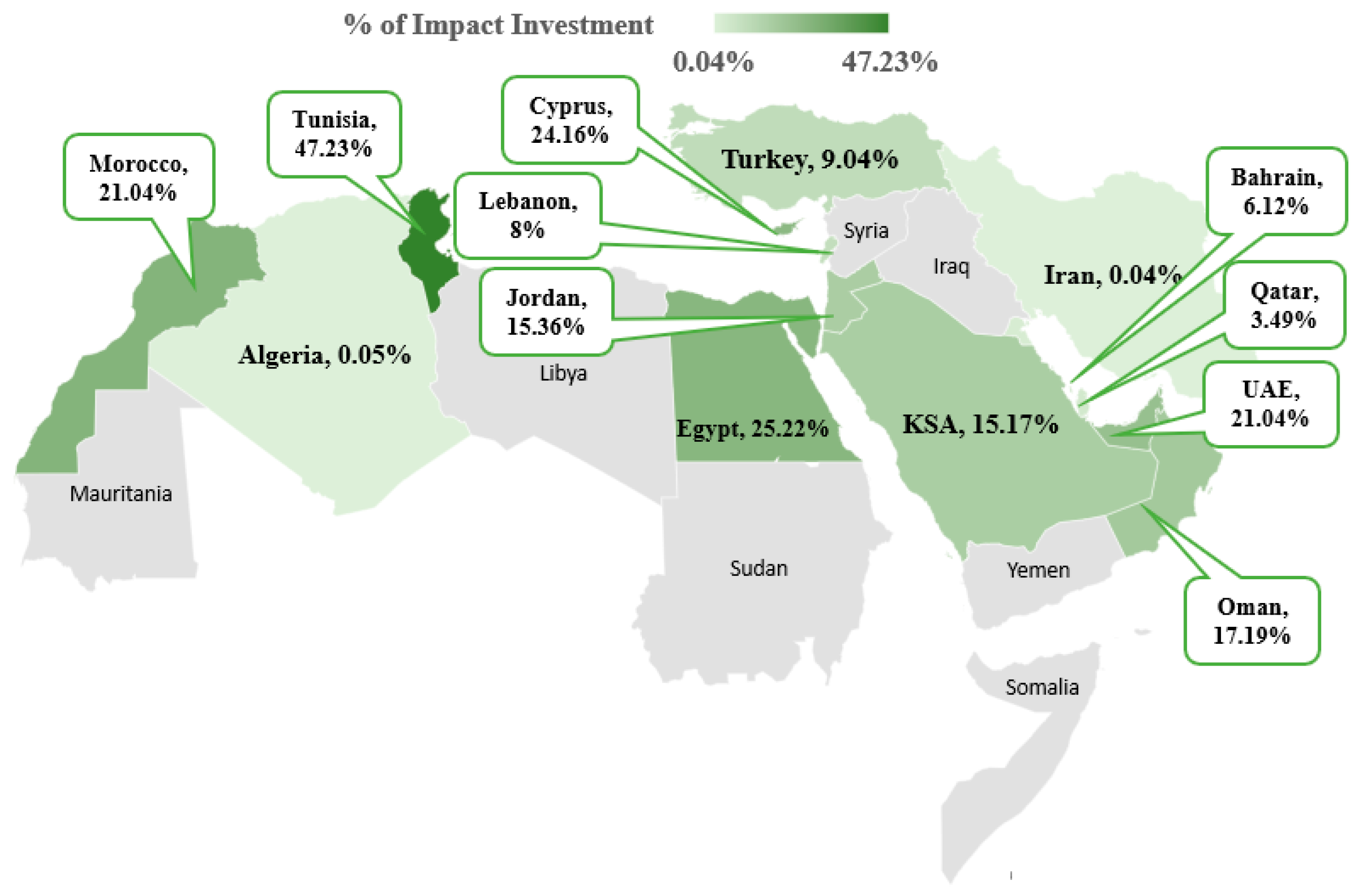

3.2. Impact Investment in the MENA Region

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

4. Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Correlation Matrix

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) lnMoneyR | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| (2) StartIMP | −0.05 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (3) CountryCode | 0.15 *** | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| (4) LOC | 0.12 *** | 0 | 0.16 *** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| (5) FundType | 0.34 *** | 0 | 0.03 ** | −0.03 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| (6) NFDeals | 0.36 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.02 | 0.05 *** | −0.02 * | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| (7) Nfounders | 0.15 *** | 0 | 0 | 0.04 ** | −0.03 * | 0.15 *** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| (8) Nempl | 0.26 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 *** | −0.02 * | −0.03 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| (9) NRound | 0.35 *** | 0.05 *** | −0.04 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.71 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.02 | 1 | |||||||||||

| (10) NInvestors | 0.43 *** | 0.01 | 0.05 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.04 ** | 0.49 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.61 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| (11) Age | 0.19 *** | 0.02 | −0.03 ** | −0.02 * | 0.38 *** | −0.1 *** | −0.06 *** | 0.35 *** | −0.02 | −0.11 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| (12) VC_Fin | 0.15 *** | 0.02 * | −0.03 ** | 0.03 ** | −0.06 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.09 *** | −0.05 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.18 *** | −0.07 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| (13) E_Com | 0.02 * | −0.14 *** | −0.03 ** | 0.04 *** | −0.05 *** | 0.03 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 ** | 0.04 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | 1 | |||||||

| (14) FinTech | 0.16 *** | −0.11 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.02 | 0.04 *** | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.06 *** | 0.16 *** | −0.08 *** | 0.02 | −0.15 *** | 1 | ||||||

| (15) IT_Sol | −0.03 ** | −0.06 *** | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 ** | −0.02 | 0.03 ** | −0.01 | −0.1 *** | −0.09 *** | 1 | |||||

| (16) Log_Transp | 0.07 *** | −0.04 *** | 0.03 ** | 0 | 0.02 | 0.05 *** | 0.04 ** | 0.06 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.09 *** | −0.08 *** | −0.05 *** | 1 | ||||

| (17) Inf_Tech | −0.03 ** | −0.07 *** | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | −0.04 *** | −0.03 ** | 0.01 | −0.05 *** | −0.05 *** | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.11 *** | −0.11 *** | −0.07 *** | −0.06 *** | 1 | |||

| (18) Energy | 0.05 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.01 | −0.05 *** | 0.08 *** | −0.03 ** | 0 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 * | 0.08 *** | −0.01 | −0.06 *** | −0.05 *** | −0.03 ** | −0.03 ** | −0.04 *** | 1 | ||

| (19) AgTech | 0 | 0.1 *** | 0.01 | 0 | 0.04 *** | 0.04 *** | 0 | 0.03 ** | 0.06 *** | 0.03 * | 0.01 | 0.02 * | −0.04 *** | −0.04 *** | −0.02 * | −0.02 * | −0.03 ** | −0.01 | 1 | |

| (20) H_Care | −0.03 * | 0.2 *** | −0.02 * | 0 | 0.02 * | −0.03 ** | −0.03 ** | 0.03 ** | −0.01 | −0.02 * | 0.04 ** | 0.02 | −0.11 *** | −0.1 *** | −0.07 *** | −0.06 *** | −0.08 *** | −0.04 *** | −0.03 ** | 1 |

| 1 | Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) is an investor initiative in partnership with the Financial Initiative of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP FI) and the United Nations (UN) Global Compact. |

| 2 | Environmental, social, and governance reflect the three key factors used to evaluate the sustainability and ethical impact of an investment. |

| 3 | A regional platform focused on startup ecosystems in the MENA region. |

References

- Agrawal, A., & Hockerts, K. (2019). Impact investing strategy: Managing conflicts between impact investor and investee social enterprise. Sustainability, 11(15), 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H., Yaqub, M., & Lee, S. H. (2023). Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: A scientometric review of global trends. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(2), 2965–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali-Yrkkö, J., Hyytinen, A., & Pajarinen, M. (2005). Does patenting increase the probability of being acquired? Evidence from cross-border and domestic acquisitions. Applied Financial Economics, 15(14), 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. M., Morse, A., & Yasuda, A. (2021). Impact investing. Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1), 162–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathaei, A., & Štreimikienė, D. (2023). Renewable energy and sustainable agriculture: Review of indicators. Sustainability, 15(19), 14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking and Finance, 22(6–8), 613–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J. H., Hirschmann, M., & Fisch, C. (2021). Which criteria matter when impact investors screen social enterprises? Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerner, H. (2012). The corporate ESG beauty contest continues: Recent developments in research and analysis. Corporate Finance Review, 17(3), 32. [Google Scholar]

- Brander, J. A., Du, Q., & Hellmann, T. (2015). The effects of government-sponsored venture capital: International evidence. Review of Finance, 19(2), 571–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstetter, L., & Lehner, O. M. (2015). Opening the market for impact investments: The need for adapted portfolio tools. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 5(2), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugg-Levine, A., & Emerson, J. (2011). Impact investing: Transforming how we make money while making a difference. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6(3), 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderini, M., Chiodo, V., & Michelucci, F. V. (2018). The social impact investment race: Toward an interpretative framework. European Business Review, 30(1), 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calopa, M. K., Horvat, J., & Lalic, M. (2014). Analysis of financing sources for startup companies. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 19(2), 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N. M., Stearns, T. M., Reynolds, P. D., & Miller, B. A. (1994). New venture strategies: Theory development with an empirical base. Strategic Management Journal, 15(1), 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collewaert, V., & Sapienza, H. J. (2016). How does angel investor-entrepreneur conflict affect venture innovation? It depends. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 40(3), 573–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M. G., D’Adda, D., & Quas, A. (2019). The geography of venture capital and entrepreneurial ventures’ demand for external equity. Research Policy, 48(5), 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M. G., Montanaro, B., & Vismara, S. (2023). What drives the valuation of entrepreneurial ventures? A map to navigate the literature and research directions. Small Business Economics, 61(1), 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, E. L., Salanță, I. I., Beleiu, I. N., Bordean, O. N., & Bunduchi, R. (2021). A systematic literature review on accelerators. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46(1), 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, A., Ughetto, E., Scellato, G., & Fontana, F. (2021). Social impact venture capital investing: An explorative study. Venture Capital, 23(4), 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I., Ioppolo, G., Shen, Y., & Rosen, M. A. (2022). Sustainability Survey: Promoting solutions to real-world problems. Sustainability, 14(19), 12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deias, A., & Magrini, A. (2023). The Impact of Equity Funding Dynamics on Venture Success: An Empirical Analysis Based on Crunchbase Data. Economies, 11(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D. J. (2004). Entrepreneurial finance: An overview of the issues and evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(2), 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Santamaría, C., & Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2021). Econometric estimation of the factors that influence startup success. Sustainability, 13(4), 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, N. O., & Bugg-Levine, A. (2010). Impact investments: An emerging asset class (Rockefeller Foundation). JP Morgan Social Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Drover, W., Busenitz, L., Matusik, S., Townsend, D., Anglin, A., & Dushnitsky, G. (2017). A review and road map of entrepreneurial equity financing research: Venture capital, corporate venture capital, angel investment, crowdfunding, and accelerators. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1820–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. (2015). Closing the loop—An EU action plan for the circular economy. In Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. EC. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, C. D., Szatmari, B., Sitruk, J. M. C., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2023). Getting off to a good start: Emerging academic fields and early-stage equity financing. Small Business Economics, 62(4), 1591–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E. d. S., Grochau, I. H., & Ten Caten, C. S. (2023). Impact investing: Determinants of external financing of social enterprises in Brazil. Sustainability, 15(15), 11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, D., & Pyka, A. (2023). Circular economy, bioeconomy, and sustainable development goals: A systematic literature review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroski, P. A. (1995). What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIIN. (2019). Core characteristics of impact investing. Global Impact Investing Network. Available online: http://www.thegiin.org (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- GIIN. (2021). Impact investing decision-making: Insights on financial performance. Global Impact Investing Network. Available online: www.thegiin.org (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Gray, J., Ashburn, N., Douglas, H. V., Jeffers, J. S., Musto, D. K., & Geczy, C. (2016). Great expectations: Mission preservation and financial performance in impact investing. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B., Lou, Y., & Pérez-Castrillo, D. (2015). Investment, duration, and exit strategies for corporate and independent venture capital-backed start-ups. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 24(2), 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, J. R. M. (2005). The value relevance of financial statements in the venture capital market. Accounting Review, 80(2), 613–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslanger, P., Lehmann, E. E., & Seitz, N. (2022). The performance effects of corporate venture capital: A meta-analysis. Journal of Technology Transfer, 48(6), 2132–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J., & Lukomnik, J. (2018). The purpose of asset management. Pension Insurance Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Hebb, T. (2013). Impact investing and responsible investing: What does it mean? Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, 3(2), 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, V., Kuncoro, A., & Turner, M. (1995). Industrial development in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höchstädter, A. K., & Scheck, B. (2015). What’s in a name: An analysis of impact investing understandings by academics and practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E. T., & Harji, K. (2012). Accelerating impact: Achievements, challenges and what’s next in building the impact investing industry. The Rockefeller Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J., Kim, J., Son, H., & Nam, D. I. (2020). The role of venture capital investment in startups’ sustainable growth and performance: Focusing on absorptive capacity and venture capitalists’ reputation. Sustainability, 12(8), 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczam, F., Siluk, J. C. M., Guimaraes, G. E., de Moura, G. L., da Silva, W. V., & da Veiga, C. P. (2022). Establishment of a typology for startups 4.0. Review of Managerial Science, 16(3), 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O., & Orpiszewski, T. (2025). Determinants of impact investments: Evidence from portfolio-level data. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Accounting, 6, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keasey, K., & Watson, R. (1991). The state of the art of small firm failure prediction: Achievements and prognosis. International Small Business Journal, 9(4), 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherbachi, S. (2023). Digital economy under fintech scope: Evidence from African investment. FinTech, 2(3), 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollenda, P. (2022). Financial returns or social impact? What motivates impact investors’ lending to firms in low-income countries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 136, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovner, A., & Lerner, J. (2015). Doing well by doing good? Community development venture capital. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 24(3), 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louche, C., Arenas, D., & van Cranenburgh, K. C. (2012). From preaching to investing: Attitudes of religious organisations towards responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(3), 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, I. C., Siegel, R., & Narasimha, P. N. S. (1985). Criteria used by venture capitalists to evaluate new venture proposals. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnitt. (2021). 2021 MENA VC impact investment report. Magnitt Report. Saudi Aramco Entrepreneurship Center Wa’ed. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, P. (1982). The Choice Between Equity and Debt: An Empirical Study. The Journal of Finance, 37(1), 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. (2013). Making impact investible. Impact Economy Working Papers, 4(4), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M. R., Wolfe, M. T., Kuratko, D. F., & Fisher, G. (2022). Examining entrepreneurial experience in relation to pre-launch and post-launch learning activities affecting venture performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(4), 759–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, A., Nor, F. M., Ramli, N. A., Basah, M. Y. A., & Aziz, M. R. A. (2023). The influence of ESG, SRI, Ethical, and impact investing activities on portfolio and financial performance—Bibliometric analysis/mapping and clustering analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(7), 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J., Portugal, P., & Guimarães, P. (1995). The survival of new plants: Start-up conditions and post-entry evolution. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogapi, E. M., Sutherland, M. M., & Wilson-Prangley, A. (2019). Impact investing in South Africa: Managing tensions between financial returns and social impact. European Business Review, 31(3), 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriesen, K. A. (2018). Impact investment market map. UNEP Financial Initiative and Global Compact. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, E., & Tenenbaum, B. H. (1993). Specialization versus diversification as a venture capital investment strategy. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(5), 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrisia, D., & Dastgir, S. (2017). Diversification and corporate social performance in manufacturing companies. Eurasian Business Review, 7(1), 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picken, J. C. (2017). From startup to scalable enterprise: Laying the foundation. Business Horizons, 60(5), 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, K., Ahmed, S. A., & Quinn, M. (2015). Data driven analysis of startup accelerators. Universal Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 3(2), 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressin, M. (2022). Start-ups as drivers of economic growth. Research in Economics, 76(4), 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J., & Müller, V. (2013). Does acquiring venture capital pay off for the funded firms? A meta-analysis on the relationship between venture capital investment and funded firm financial performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltuk, Y., & El Idrissi, A. (2015). Impact assessment in practice. J.P. Morgan Global Social Finance Research. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, N., Lehmann, E. E., & Haslanger, P. (2023). Corporate accelerators: Design and startup performance. Small Business Economics, 62(4), 1615–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuwaikh, F., & Dubocage, E. (2022). Access to the corporate investors’ complementary resources: A leverage for innovation in biotech venture capital-backed companies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefkes, M., Bjørgum, Ø., & Sørheim, R. (2025). Business angels investing in green ventures: How do they add value to their start-ups? Venture Capital, 27(1), 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., & Mungila Hillemane, B. S. (2023). An analysis of the financial performance of tech startups: Do quantum and sources of finance make a difference in India? Small Enterprise Research, 30(3), 374–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słowiński, R., Zopounidis, C., & Dimitras, A. I. (1997). Prediction of company acquisition in Greece by means of the rough set approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 100(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D. J. (1985). The problems facing new firms. Journal of Management Studies, 22(3), 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Te, Y. F., Wieland, M., Frey, M., Pyatigorskaya, A., Schiffer, P., & Grabner, H. (2023). Making it into a successful series a funding: An analysis of Crunchbase and LinkedIn data. Journal of Finance and Data Science, 9, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, E., Dell’Acqua, A., & Bovsunovsky, A. (2024). Diversification and size in venture capital investing. Eurasian Business Review, 14(2), 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelstad, B. (2016). Impact investing: A brief history. Capitalism and Society, 11(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Trinks, P. J., & Scholtens, B. (2017). The opportunity cost of negative screening in socially responsible investing. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykvová, T. (2018). Legal framework quality and success of (different types of) venture capital investments. Journal of Banking and Finance, 87, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M. (2004). Banks versus venture capital: Project evaluation, screening, and expropriation. Journal of Finance, 59(2), 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. (1994). The post-entry performance of new small firms in German manufacturing industries. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(2), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. E. (2014). Social investment: New investment approaches for addressing social and economic challenges. SSRN Electronic Journal, 15, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, B. (2021). Impact investing: A review of the current state and opportunities for development. Istanbul Business Research, 50(1), 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata-Molina, C., Bedoya-Villa, M., Castro-Gómez, J., Gutiérrez-Broncano, S., Román, E., & Rave-Gómez, E. (2025). Factors affecting the financial sustainability of startups during the valley of death: An empirical study in an innovative ecosystem. International Journal of Financial Studies, 13(2), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhyber, T. V., Lihonenko, L. O., Piskunova, O. V., Srivastava, P., & Huzik, T. A. (2021). Logit-model for predicting startup’s venture funding. Socio-Economic Problems of the Modern Period of Ukraine, 5(151), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algeria | Bahrain | Cyprus | Egypt | Iran | Jordan | |||||||

| Sectors | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD |

| 3D Technology | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3(3) | 0.12 | 2(2) | 0.17 | 1(1) | 0.03 |

| Advertising, Media, and Entertainment | 6(4) | 55.16 | 5(1) | 0.13 | 37(27) | 49.09 | 33(23) | 20.96 | 17(15) | 4.67 | 42(30) | 57.96 |

| Aerospace and Defense | 1(1) | 0.11 | - | - | 1(1) | 2.10 | 1(1) | 0.01 | - | - | 3(2) | 7.00 |

| AgTech | 1(1) | 0.08 | - | - | 1(1) | 17.46 | 8(4) | 0.38 | - | - | 2(1) | 0.10 |

| Artificial Intelligence | 2(2) | 0.22 | 5(2) | 13.80 | 16(13) | 10.90 | 26(18) | 7.30 | 1(0) | - | 12(10) | 3.59 |

| Data Analytics and Business Intelligence | 3(3) | 0.28 | - | - | 11(9) | 5.34 | 7(3) | 0.58 | 1(1) | 1.40 | 6(5) | 0.99 |

| E-Commerce | 4(2) | 0.05 | 15(13) | 7.23 | 9(7) | 19.19 | 148(106) | 604.79 | 15(9) | 11.13 | 52(39) | 67.19 |

| EdTech | 1(1) | 0.08 | 8(7) | 0.99 | 14(9) | 83.26 | 33(23) | 10.35 | 3(2) | 0.02 | 37(26) | 40.36 |

| Energy | 1(0) | - | - | - | 5(2) | 10.03 | 15(9) | 46.84 | - | - | 2(2) | 0.60 |

| Enterprise Software | 4(4) | 0.15 | 18(9) | 3.12 | 33(28) | 38.54 | 79(60) | 45.75 | 3(2) | 0.20 | 18(14) | 5.72 |

| Fashion and Lifestyle | 3(3) | 0.10 | - | - | 2(2) | 7.30 | 10(6) | 0.46 | 1(1) | 0.23 | 10(4) | 0.44 |

| FinTech | 2(2) | 0.10 | 14(11) | 268.39 | 56(45) | 233.90 | 101(66) | 715.29 | 10(3) | 0.71 | 28(26) | 298.84 |

| Food and Beverage | 1(0) | - | 12(8) | 28.99 | 1(1) | 0.18 | 33(27) | 63.62 | - | - | 9(6) | 0.97 |

| Gaming | - | - | 1(1) | 0.07 | 34(23) | 60.44 | 17(12) | 6.35 | - | - | 14(8) | 24.90 |

| Health Care | 2(0) | - | 7(5) | 0.40 | 12(7) | 5.18 | 83(53) | 75.90 | 7(2) | 0.15 | 15(13) | 55.01 |

| Home Services | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13(8) | 3.49 | 1(0) | - | 3(3) | 0.04 |

| Information Technology | 12(7) | 217.74 | 4(3) | 2.65 | 12(11) | 108.72 | 58(40) | 35.91 | 5(3) | 1.12 | 21(9) | 0.74 |

| Intelligent Systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1(1) | 0.10 | - | - | - | - |

| IT Solutions | 4(3) | 5.85 | 2(2) | 2.55 | 20(17) | 13.91 | 47(30) | 34.17 | 6(5) | 296.36 | 19(14) | 187.10 |

| Logistics Transportation | 4(1) | 0.16 | - | - | 7(5) | 25.50 | 43(33) | 219.82 | 1(1) | 22.39 | 2(0) | - |

| Others | 9(9) | 0.79 | 2(2) | 6.30 | 19(12) | 35.04 | 19(12) | 3.81 | 5(5) | 3.04 | 11(9) | 3.42 |

| Travel and Tourism | - | - | 3(3) | 0.08 | 13(11) | 7.70 | 8(7) | 1.82 | 6(5) | 27.60 | 1(1) | 0.03 |

| Grand Total | 60(43) | 280.85 | 96(67) | 334.71 | 303(231) | 733.78 | 786(545) | 1897.79 | 84(56) | 369.19 | 308(223) | 755.02 |

| Kuwait | Lebanon | Morocco | Oman | Qatar | Saudi Arabia | |||||||

| Sectors | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD |

| 3D Technology | - | - | 1(1) | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Advertising, Media, and Entertainment | 5(4) | 0.83 | 24(15) | 21.73 | 5(4) | 125.47 | 5(4) | 125.47 | 3(3) | 7.02 | 3(3) | 0.09 |

| Aerospace and Defense | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| AgTech | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1(0) | - | - | - |

| Artificial Intelligence | - | - | 14(12) | 2.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Data Analytics and Business Intelligence | - | - | 4(4) | 6.52 | - | - | - | - | 1(1) | 0.50 | 4(3) | 0.39 |

| E-Commerce | 12(8) | 23.15 | 12(6) | 2.62 | 5(3) | 0.45 | 5(3) | 0.45 | 11(6) | 2.01 | 8(5) | 11.20 |

| EdTech | 6(3) | 7.50 | 5(3) | 0.44 | 2(1) | 0.05 | 2(1) | 0.05 | 2(1) | 0.03 | - | - |

| Energy | - | - | 4(0) | - | - | - | - | - | 1(0) | - | - | - |

| Enterprise Software | 22(14) | 66.55 | 17(11) | 5.33 | 1(1) | 0.16 | 1(1) | 0.16 | 3(2) | 0.11 | 8(7) | 4.14 |

| Fashion and Lifestyle | 2(1) | 45.00 | 7(6) | 3.98 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FinTech | 7(6) | 7.15 | 18(12) | 26.06 | 7(5) | 18.98 | 7(5) | 18.98 | - | - | 3(3) | 0.96 |

| Food and Beverage | 6(2) | 1.43 | 15(9) | 23.53 | - | - | - | - | 3(2) | 1.65 | - | - |

| Gaming | - | - | 12(8) | 3.16 | - | - | - | - | 1(1) | 0.13 | - | - |

| Health Care | 6(5) | 3.71 | 15(10) | 4.05 | 6(6) | 8.30 | 6(6) | 8.30 | 2(2) | 0.36 | - | - |

| Home Services | - | - | 2(2) | 13.70 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Information Technology | 3(1) | 8.49 | 6(6) | 5.66 | 6(6) | 17.31 | 6(6) | 17.31 | 6(6) | 3.10 | 2(1) | 0.08 |

| Intelligent Systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IT Solutions | 1(0) | - | 5(3) | 20.33 | 2(2) | 9.00 | 2(2) | 9.00 | - | - | 1(0) | - |

| Logistics Transportation | 2(1) | 3.00 | 3(1) | 0.50 | 5(3) | 17.27 | 5(3) | 17.27 | 3(2) | 10.54 | - | - |

| Others | 2(1) | 520.00 | 4(0) | - | 1(1) | 0.12 | 1(1) | 0.12 | 2(1) | 8.00 | 1(0) | - |

| Travel and Tourism | - | - | 1(0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2(1) | 2.50 |

| Grand Total | 74(46) | 686.82 | 169(109) | 139.82 | 40(32) | 197.11 | 40(32) | 197.11 | 39(27) | 33.45 | 32(23) | 19.35 |

| Tunisia | Turkey | United Arab Emirates | Other Countries | All MENA Countries | ||||||||

| Sectors | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | AR(F) | MR in M USD | ||

| 3D Technology | 6(5) | 0.49 | 21(17) | 10.34 | 13(10) | 14.83 | - | - | 51(43) | 58.10 | ||

| Advertising, Media, and Entertainment | 6(2) | 0.14 | 142(94) | 88.41 | 118(81) | 605.92 | 6(6) | 7.11 | 478(330) | 1067.86 | ||

| Aerospace and Defense | 5(5) | 1.98 | 13(8) | 10.89 | 15(11) | 17.75 | - | - | 54(40) | 55.90 | ||

| AgTech | 7(6) | 1.43 | 28(23) | 24.32 | 20(16) | 589.51 | 1(0) | 78(62) | 674.82 | |||

| Artificial Intelligence | 4(4) | 0.35 | 132(105) | 51.16 | 69(41) | 41.05 | - | - | 325(233) | 197.79 | ||

| Data Analytics and Business Intelligence | 4(2) | 0.89 | 49(33) | 40.67 | 26(20) | 9.97 | 5(4) | 0.89 | 129(94) | 138.37 | ||

| E-Commerce | 12(11) | 1.68 | 249(178) | 816.14 | 243(174) | 1439.22 | 19(11) | 13.21 | 954(676) | 3864.71 | ||

| EdTech | 18(16) | 13.72 | 70(54) | 20.57 | 77(52) | 137.89 | 2(1) | 0.03 | 325(227) | 353.88 | ||

| Energy | 7(4) | 1.82 | 47(32) | 95.88 | 22(16) | 748.49 | 1(0) | - | 117(72) | 1158.42 | ||

| Enterprise Software | 8(8) | 5.35 | 195(134) | 155.81 | 124(85) | 114.61 | 11(9) | 4.25 | 624(441) | 728.21 | ||

| Fashion & Lifestyle | 3(2) | 0.63 | 21(11) | 7.27 | 20(10) | 85.81 | - | - | 88(52) | 153.66 | ||

| FinTech | 19(14) | 40.65 | 177(124) | 249.28 | 382(251) | 1317.39 | 3(3) | 0.96 | 924(627) | 3998.88 | ||

| Food and Beverage | 3(1) | 10.23 | 65(46) | 88.58 | 68(46) | 192.27 | 3(2) | 1.65 | 249(167) | 456.47 | ||

| Gaming | 3(2) | 0.22 | 131(91) | 779.51 | 22(21) | 179.41 | 1(1) | 0.13 | 247(177) | 1058.24 | ||

| Health Care | 7(4) | 18.83 | 127(85) | 99.09 | 106(75) | 699.32 | 2(2) | 0.36 | 459(307) | 1147.10 | ||

| Home Services | - | - | 28(20) | 158.39 | 14(8) | 11.46 | - | - | 86(61) | 199.18 | ||

| Information Technology | 11(4) | 0.69 | 120(80) | 114.00 | 146(96) | 1008.33 | 8(7) | 3.18 | 466(309) | 1634.95 | ||

| Intelligent Systems | - | - | 10(8) | 6.04 | 1(0) | - | - | - | 28(22) | 72.17 | ||

| IT Solutions | 4(4) | 0.77 | 105(80) | 81.70 | 87(65) | 1240.66 | 1(0) | - | 347(251) | 1935.52 | ||

| Logistics Transportation | 13(12) | 3.66 | 100(81) | 254.21 | 113(76) | 1282.78 | 3(2) | 10.54 | 376(274) | 2127.46 | ||

| Others | 2(1) | 0.10 | 61(37) | 43.66 | 74(47) | 658.90 | 3(1) | 8.00 | 240(152) | 1326.15 | ||

| Travel and Tourism | 4(3) | 0.24 | 30(21) | 33.62 | 49(37) | 81.64 | 2(1) | 2.50 | 127(96) | 171.41 | ||

| Grand Total | 146(110) | 103.86 | 1921(1362) | 3229.56 | 1809(1238) | 10,477.19 | 71(50) | 52.80 | 6772(4713) | 22,579.26 | ||

| Sector/Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Technology | - | 1.0 | - | - | - | 0.4 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 30.1 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 58.1 |

| Ad. Med., and Ent | - | 3.5 | 12.3 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 11.9 | 17.3 | 214.9 | 12.7 | 39.6 | 73.4 | 26.3 | 563.5 | 33.5 | 38.1 | 1067.9 |

| Aer. and Def. | - | - | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 3.4 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 12.6 | 55.9 |

| AgTech | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.5 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 48.1 | 105.8 | 502.0 | 2.3 | 674.8 |

| Art. Int. | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 62.7 | 39.6 | 39.0 | 16.0 | 197.8 |

| D. A. and Bus. Int | 0.5 | - | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 5.4 | 15.3 | 10.6 | 3.8 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 16.5 | 71.2 | 0.8 | 138.4 |

| E-Commerce | - | 20.7 | 35.4 | 122.1 | 84.2 | 88.4 | 61.5 | 392.8 | 101.3 | 339.5 | 221.7 | 272.1 | 821.5 | 745.6 | 557.9 | 3864.7 |

| EdTech | 14.0 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 5.6 | 21.6 | 0.7 | 22.4 | 3.7 | 34.4 | 95.1 | 12.1 | 85.3 | 34.4 | 17.3 | 353.9 |

| Energy | - | - | 65.3 | 0.5 | - | 75.0 | 0.3 | 7.5 | 20.6 | 1.7 | 94.7 | 7.2 | 4.0 | 720.0 | 161.4 | 1158.4 |

| Ent. Sof. | 16.5 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 24.2 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 52.5 | 13.2 | 15.3 | 40.1 | 81.1 | 101.5 | 281.6 | 83.6 | 728.2 |

| Fash. and Life. | - | - | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 46.7 | 2.3 | 51.2 | 5.6 | 11.1 | 31.5 | 153.7 |

| FinTech | 4.0 | 1.1 | 63.9 | 33.9 | 6.6 | 14.4 | 124.6 | 205.2 | 110.4 | 103.1 | 183.1 | 312.4 | 918.5 | 1391.2 | 526.5 | 3998.9 |

| Food and Bev. | - | - | - | 44.0 | 0.0 | - | 13.6 | 7.9 | 0.8 | 11.3 | 16.9 | 62.9 | 156.8 | 94.0 | 48.2 | 456.5 |

| Gaming | 5.7 | 11.5 | 17.5 | 0.6 | 21.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 12.6 | 18.1 | 378.5 | 549.8 | 34.4 | 1058.2 |

| Health Care | 4.0 | 12.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 56.5 | 361.4 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 71.5 | 68.4 | 18.7 | 94.9 | 116.9 | 117.4 | 208.1 | 1147.1 |

| Home Services | - | - | 13.5 | - | 0.5 | - | 1.6 | 9.4 | 11.5 | 14.5 | 2.5 | 132.6 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 199.2 |

| Inf. Tech. | 0.5 | 16.6 | 0.7 | 15.4 | 3.4 | 6.5 | 23.8 | 3.6 | 71.4 | 24.1 | 22.7 | 81.9 | 196.7 | 1134.2 | 33.3 | 1635.0 |

| Int. Sys. | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.7 | 0.5 | 54.7 | 1.4 | 9.0 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 72.2 |

| IT Solutions | 11.6 | 15.2 | 12.3 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 176.5 | 36.1 | 307.9 | 192.7 | 70.3 | 73.8 | 610.2 | 394.0 | 23.6 | 1935.5 |

| Log. Transp. | - | - | - | - | 11.7 | 17.0 | 77.0 | 379.7 | 298.0 | 258.9 | 182.7 | 141.4 | 393.3 | 326.3 | 41.3 | 2127.5 |

| Others | - | - | 8.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 32.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 5.5 | 544.4 | 22.4 | 103.3 | 442.6 | 16.8 | 149.4 | 1326.2 |

| Trav. and Tour. | - | - | 0.0 | - | 0.4 | 1.3 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 12.5 | 6.2 | 10.5 | 4.1 | 33.6 | 171.4 |

| All | 57.2 | 89.2 | 234.9 | 255.7 | 218.5 | 646.7 | 533.4 | 1383.2 | 1135.9 | 1767.5 | 1153.0 | 1598.8 | 4990.8 | 6485.5 | 2029.0 | 22,579.3 |

Ranked first in value of financed deals;

Ranked first in value of financed deals;  Ranked second in value of financed deals;

Ranked second in value of financed deals;  Ranked third in value of financed deals.

Ranked third in value of financed deals.| Types of Investors | Number of Investors | Headquarters in Capital | Number of Investments | Number of Exits | Number of Portfolio Organizations | Number of Lead Investments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venture capital | 361 (36) | 309 (28) | 3756 (356) | 233 (19) | 3108 (308) | 1135 (151) |

| Private equity firm | 99 (17) | 83 (14) | 321 (253) | 39 (39) | 292 (231) | 129 (111) |

| Corporate venture capital | 32 (2) | 25 (1) | 277 (49) | 21 (0) | 226 (41) | 114 (41) |

| Micro VC | 23 (1) | 18 (1) | 332 (1) | 31 (0) | 250 (1) | 109 (0) |

| VC and micro VC | 12 (1) | 8 (1) | 115 (2) | 7 (2) | 97 (2) | 46 (1) |

| VC and private equity | 45 (7) | 41 (5) | 337 (28) | 36 (3) | 299 (25) | 134 (11) |

| PE/VC/CVC and other partners | 84 (10) | 73 (8) | 1247 (136) | 98 (13) | 1027 (112) | 371 (38) |

| Individual/angel | 673 (34) | 436 (24) | 1245 (65) | 94 (10) | 1144 (62) | 156 (13) |

| Angel group | 33 (1) | 29 (1) | 345 (45) | 29 (2) | 293 (31) | 79 (9) |

| Investment partner, individual/angel | 97 (6) | 63 (4) | 616 (42) | 41 (0) | 481 (35) | 48 (5) |

| Angel group and other partners | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 130 (29) | 34 (2) | 114 (24) | 59 (5) |

| Accelerator | 46 (8) | 40 (6) | 612 (42) | 19 (0) | 575 (40) | 211 (25) |

| Accelerator and other partners | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | 38 (193) | 0 (6) | 36 (192) | 15 (56) |

| Family investment office | 32 (3) | 28 (3) | 166 (15) | 25 (1) | 137 (14) | 48 (6) |

| Incubator | 19 (3) | 19 (2) | 70 (8) | 3 (0) | 69 (7) | 45 (4) |

| Investment bank | 58 (4) | 53 (2) | 216 (5) | 33 (1) | 192 (5) | 105 (3) |

| Others | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 12 (5) | 3 (0) | 12 (5) | 3 (1) |

| Conventional investors (impact investors) | 1633 (138) | 1241 (105) | 9835 (1274) | 746 (98) | 8352 (1135) | 2807 (480) |

| All investors | 1771 | 1346 | 11,109 | 844 | 9487 | 3287 |

| Variable | Definition | Type of Variable | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headquarter of startup | Location of startup | Dichotomous: startup in the country’s capital = 1; 0, otherwise | (Henderson et al., 1995; Storey, 1994; Carter et al., 1994; Tykvová, 2018; Colombo et al., 2019) |

| Startup age | Age of company in years | Continuous | (Geroski, 1995; Singh & Mungila Hillemane, 2023; Berger & Udell, 1998) |

| Size of the startup | Number of employees | Continuous | (Keasey & Watson, 1991; Mata et al., 1995; Storey, 1985; Berger & Udell, 1998) |

| Investment | Number of investors Number of funders | Continuous | (Wagner, 1994; Storey, 1994; Rosenbusch et al., 2013; Collewaert & Sapienza, 2016) |

| Financing | Number of rounds Number of financed deals | Continuous | (Hand, 2005; Guo et al., 2015; Shuwaikh & Dubocage, 2022) |

| VC financing startups | Obtained finance from VC | Dichotomous; funded VC = 1; 0, otherwise | (Calopa et al., 2014; Singh & Mungila Hillemane, 2023) |

| Sector groups (top five sectors) | Impact startups: Fintech, logistics transportation, energy, agtech, health care. Conventional startups: E-commerce, fintech, IT solutions, logistics transportation, information technology | Dichotomous: e.g., startup invests in e-commerce = 1; 0, otherwise | (Croce et al., 2021; Jeong et al., 2020) |

| Type of funding (last funding type) | 1 = pre-seed, 2 = seed, 3 = series a, 4 = series b, 5 = series c, 6 = series d, 7 = series f, 8 = angel, 9 = corporate round, 10 = equity crowdfunding, 11 = initial coin offering, 12 = equity after initial public offering, 13 = private equity, 14 = undisclosed venture series, 15 = unknown or unfunded | The numerical values assigned do not imply any inherent order or ranking among the countries | (Croce et al., 2021) |

| Variables | Variable Label | All the Sample | Impact Startups | Conventional Startups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | ||

| TEFA (in USD) | TAFA | 7,129,543 | 37,744,782 | 3167 | 5,530,845 | 14,594,226 | 711 | 7,595,297 | 39,883,433 | 2456 |

| First Funding (in USD) | First funding | 3,642,087 | 22,294,330 | 3167 | 2,551,980 | 14,545,457 | 711 | 3,957,668 | 24,069,783 | 2456 |

| lnTEFA | lnTEFA | 13.22 | 2.20 | 3167 | 13.04 | 2.09 | 711 | 13.28 | 2.22 | 2456 |

| Startup Impact | StartIMP | 0.22 | 0.41 | 4381 | ||||||

| Localization | LOC | 0.80 | 0.40 | 4381 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 961 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 3420 |

| Funding Type | FundType | 4.18 | 4.44 | 4298 | 4.19 | 4.52 | 936 | 4.18 | 4.42 | 3362 |

| Number Funded Deals | NFDeals | 1.08 | 1.07 | 4381 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 961 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 3420 |

| Number of Founders | Nfounders | 1.81 | 0.95 | 3204 | 1.82 | 0.93 | 734 | 1.81 | 0.96 | 2470 |

| Number of Employees | Nempl | 150 | 830 | 4091 | 193 | 1061 | 908 | 138 | 751 | 3183 |

| Number of Rounds | NRound | 1.74 | 1.36 | 4310 | 1.85 | 1.55 | 942 | 1.70 | 1.29 | 3368 |

| Number of Investors | NInvestors | 2.77 | 3.28 | 3249 | 2.82 | 3.22 | 724 | 2.75 | 3.29 | 2525 |

| Startup Age | Age | 6.00 | 3.95 | 4193 | 5.75 | 3.62 | 921 | 6.07 | 4.04 | 3272 |

| VC Funding | VC_Fin | 0.32 | 0.47 | 4381 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 961 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 3420 |

| E-Commerce | E_Com | 0.13 | 0.34 | 4381 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 3420 | |||

| FinTech | FinTech | 0.12 | 0.33 | 4381 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 961 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 3420 |

| IT Solutions | IT_Sol | 0.06 | 0.23 | 4381 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 3420 | |||

| Logistics Transportation | Log_Transp | 0.05 | 0.21 | 4381 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 961 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 3420 |

| Information Technology | Inf_Tech | 0.08 | 0.27 | 4381 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 3420 | |||

| Energy | Energy | 0.02 | 0.14 | 4381 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 961 | |||

| AgTech | AgTech | 0.01 | 0.10 | 4381 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 961 | |||

| Health Care | H_Care | 0.07 | 0.26 | 4381 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 961 | |||

| Null Hypothesis, the Distribution of | Sig. | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| The distribution TEFA is the same across categories of startups | 0.007 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| The distribution of first round is the same across categories of startups | 0.001 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| The distribution of number of deals is the same across categories of startups | 0.098 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| The distribution of number of employees is the same across categories of startups | 0.078 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| The distribution of announced rounds is the same across categories of startups | 0.005 | Reject the null hypothesis |

| Models | Model 1: All Startups (N = 2302) | Model 2: Impact Startups (N = 532) | Model 3: Conventional Startups (N = 1770) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Beta | t-Test | TOL | VIF | Beta | t-Test | TOL | VIF | Beta | t-Test | TOL | VIF |

| (Constant) | 10.148 *** | 70.57 | 10.326 *** | 37.89 | 10.033 *** | 61.17 | ||||||

| StartIMP | −0.047 *** | −2.77 | 0.902 | 1.109 | ||||||||

| CountryCode | 0.108 *** | 6.56 | 0.954 | 1.048 | 0.078 ** | 2.32 | 0.960 | 1.042 | 0.117 *** | 6.20 | 0.948 | 1.055 |

| LOC | 0.061 *** | 3.71 | 0.956 | 1.046 | 0.038 | 1.11 | 0.964 | 1.037 | 0.067 *** | 3.56 | 0.951 | 1.051 |

| FundType | 0.266 *** | 15.01 | 0.812 | 1.231 | 0.177 *** | 4.73 | 0.771 | 1.297 | 0.287 *** | 14.23 | 0.823 | 1.215 |

| NFDeals | 0.262 *** | 11.24 | 0.472 | 2.117 | 0.348 *** | 7.21 | 0.465 | 2.152 | 0.236 *** | 8.87 | 0.474 | 2.111 |

| Nfounders | 0.073 *** | 4.43 | 0.942 | 1.062 | 0.047 | 1.37 | 0.920 | 1.087 | 0.076 *** | 4.02 | 0.941 | 1.063 |

| Nempl | 0.165 *** | 9.51 | 0.851 | 1.175 | 0.161 *** | 4.27 | 0.764 | 1.309 | 0.165 *** | 8.45 | 0.877 | 1.140 |

| NRounds | −0.078 *** | −2.99 | 0.375 | 2.669 | −0.114 ** | −2.13 | 0.377 | 2.653 | −0.066 ** | −2.18 | 0.373 | 2.684 |

| Ninvestors | 0.287 *** | 13.65 | 0.578 | 1.731 | 0.283 *** | 6.64 | 0.597 | 1.676 | 0.289 *** | 11.91 | 0.567 | 1.764 |

| Age | 0.104 *** | 5.62 | 0.749 | 1.335 | 0.193 *** | 4.88 | 0.695 | 1.438 | 0.086 *** | 4.13 | 0.771 | 1.298 |

| VC_Fin | 0.096 *** | 5.79 | 0.935 | 1.070 | 0.098 *** | 2.87 | 0.935 | 1.069 | 0.095 *** | 5.01 | 0.930 | 1.075 |

| E_Com | 0.038 ** | 2.17 | 0.864 | 1.158 | 0.042 | 2.16 | 0.889 | 1.124 | ||||

| FinTech | 0.112 *** | 6.46 | 0.854 | 1.171 | 0.078 ** | 2.31 | 0.956 | 1.046 | 0.116 *** | 5.90 | 0.868 | 1.151 |

| IT_Sol | −0.007 | −0.42 | 0.937 | 1.068 | −0.009 | −0.44 | 0.944 | 1.059 | ||||

| Log_Transp | 0.036 ** | 2.17 | 0.938 | 1.066 | 0.068 ** | 1.99 | 0.934 | 1.070 | 0.031 * | 1.64 | 0.949 | 1.054 |

| Inf_Tech | 0.004 | 0.23 | 0.919 | 1.088 | 0.007 | 0.33 | 0.931 | 1.074 | ||||

| Energy | 0.048 *** | 2.91 | 0.960 | 1.041 | 0.135 *** | 4.01 | 0.952 | 1.050 | ||||

| AgTech | −0.017 | −0.99 | 0.975 | 1.026 | 0.008 | 0.24 | 0.961 | 1.040 | ||||

| H_Care | 0.004 | 0.23 | 0.903 | 1.108 | 0.04 | 1.18 | 0.951 | 1.052 | ||||

| R2 | 0.418 | 0.444 | 0.416 | |||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.413 | 0.428 | 0.411 | |||||||||

| Fisher | 86.23 *** | 27.48 *** | 83.24 *** | |||||||||

| Durbin-Watson | 2.047 | 1.936 | 1.968 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mseddi, S. Financing Startups and Impact Investing: Evidence Across MENA Countries. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010007

Mseddi S. Financing Startups and Impact Investing: Evidence Across MENA Countries. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleMseddi, Slim. 2026. "Financing Startups and Impact Investing: Evidence Across MENA Countries" International Journal of Financial Studies 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010007

APA StyleMseddi, S. (2026). Financing Startups and Impact Investing: Evidence Across MENA Countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010007