1. Introduction

IPO markets exhibit pronounced non-linearities, structural instability, and time-varying dynamics that render standard linear models inadequate. The dramatic swings from dot-com euphoria to post-financial crisis paralysis to pandemic-era surges suggest that IPO activity operates under distinct market regimes rather than following a stable data-generating process. Modeling these dynamics requires an approach that can both identify regime boundaries endogenously and account for the count data properties of IPO volume.

Our study extends

Greene’s (

2008) negative binomial regression framework by incorporating endogenous structural breaks identified through Bai-Perron multiple breakpoint regression testing to model the dynamics of U.S. IPO volume. We hypothesize that the decision to pursue an IPO is time- and state-dependent, captured simultaneously by structural breaks, market uncertainty, financing costs, and momentum effects. We focus on net IPOs (IPOs), defined as traditional IPOs excluding SPACs, direct listings, and other non-standard offerings.

To test this hypothesis, we first employ a Bai-Perron multiple breakpoint regression to identify structural breaks in IPO volume. We then examine the variance and median for IPOs for each of the Bai-Perron structural break regimes to assess if there are differences across time periods. Next, we model IPO activity with a negative binomial regression model. Our independent variables are the one-month lag of IPOs, the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index (VIX), and the market yield on U.S. Treasury securities at 10-year constant maturity (DGS10). We include five structural break indicator variables to capture the non-linearities and regime switches in the IPO market.

The results confirm our hypothesis, revealing distinct IPO regimes with notably different variances and medians. A traditional OLS model

1 without breaks incorrectly suggests that higher interest rates increase IPO activity, which contradicts sound financial theory. In contrast, our negative binomial regression with structural breaks reveals that market uncertainty (VIX) and financing costs (10-year rates) reduce IPO activity, while the one-month lag of IPO volume drives current period activity, properly accounting for count data characteristics and severe overdispersion.

3. Data

Our research is based on the monthly IPO volume for NYSE-, Nasdaq-, and AMEX-listed stocks, as reported on Jay Ritter’s website (

Ritter, 2025). This series includes only completed offerings; withdrawn filings are excluded, and re-registered offerings that are ultimately completed are counted once at their completion date. The average monthly values of VIX and DGS10, quoted on an investment basis, were extracted from the St. Louis FRED Database for the January 1995 to December 2024 sample period, which includes 360 observations. We begin our sample in 1995 to focus on the modern IPO market structure, avoiding potential confounding effects from the Savings and Loan crisis resolution and early Nasdaq structural changes.

We select explanatory variables based on established theories of IPO timing. VIX captures market uncertainty, which

Dicle and Levendis (

2018) and

Beaulieu and Bouden (

2015) show significantly affects IPO activity. The 10-year Treasury rate (DGS10) represents financing costs, as higher rates increase the cost of capital and make equity issuance relatively less attractive (

Pástor & Veronesi, 2005). Consistent with prior research, we include lagged IPO volume to capture persistence in IPO activity (

Brailsford et al., 2004).

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the examined variables. The data distributions of IPOs, VIX, and DGS10 are leptokurtic, with excess kurtosis values of 8.658, 9.300, and 2.175, respectively, indicating a strong prevalence of tail risks. The wide range of 0 to 151 for IPOs, along with its high excess kurtosis, reflects the volatile, cyclical, and time-varying nature of the IPO market.

The ADF and ADF Breakpoint are the Dickey–Fuller and Dickey–Fuller breakpoint unit root tests for the trend and intercept. IPO volume shows marginal evidence of stationarity (p-value = 0.083) under standard tests but clear stationarity (p < 0.01) when structural breaks are accounted for. Similarly, interest rates are non-stationary under conventional tests but achieve stationarity at the 5% level when breaks are modeled (p = 0.0199), demonstrating that ignoring structural breaks can lead to unnecessary variable transformations, which can result in incorrect statistical inference and inappropriate model specifications. VIX is stationary at 1% under both specifications, with the break test providing stronger evidence. The dramatic improvement in stationarity evidence when accounting for breaks (p < 0.01 versus p = 0.083 for IPOs) validates that our identified regimes represent genuine structural shifts in market dynamics.

4. Results

To identify structural breaks in IPO volume, we employ the

Bai and Perron (

2003) multiple breakpoint test:

where c

j represents the mean IPO level in regime j, I

jt is an indicator variable equal to 1 when observation t belongs to regime j (and 0 otherwise), and the break dates are endogenously determined by minimizing the sum of squared residuals of the time periods and statistically testing them with F-statistics. We test sequentially for L + 1 versus L breaks with 10% trimming and a maximum of five breaks.

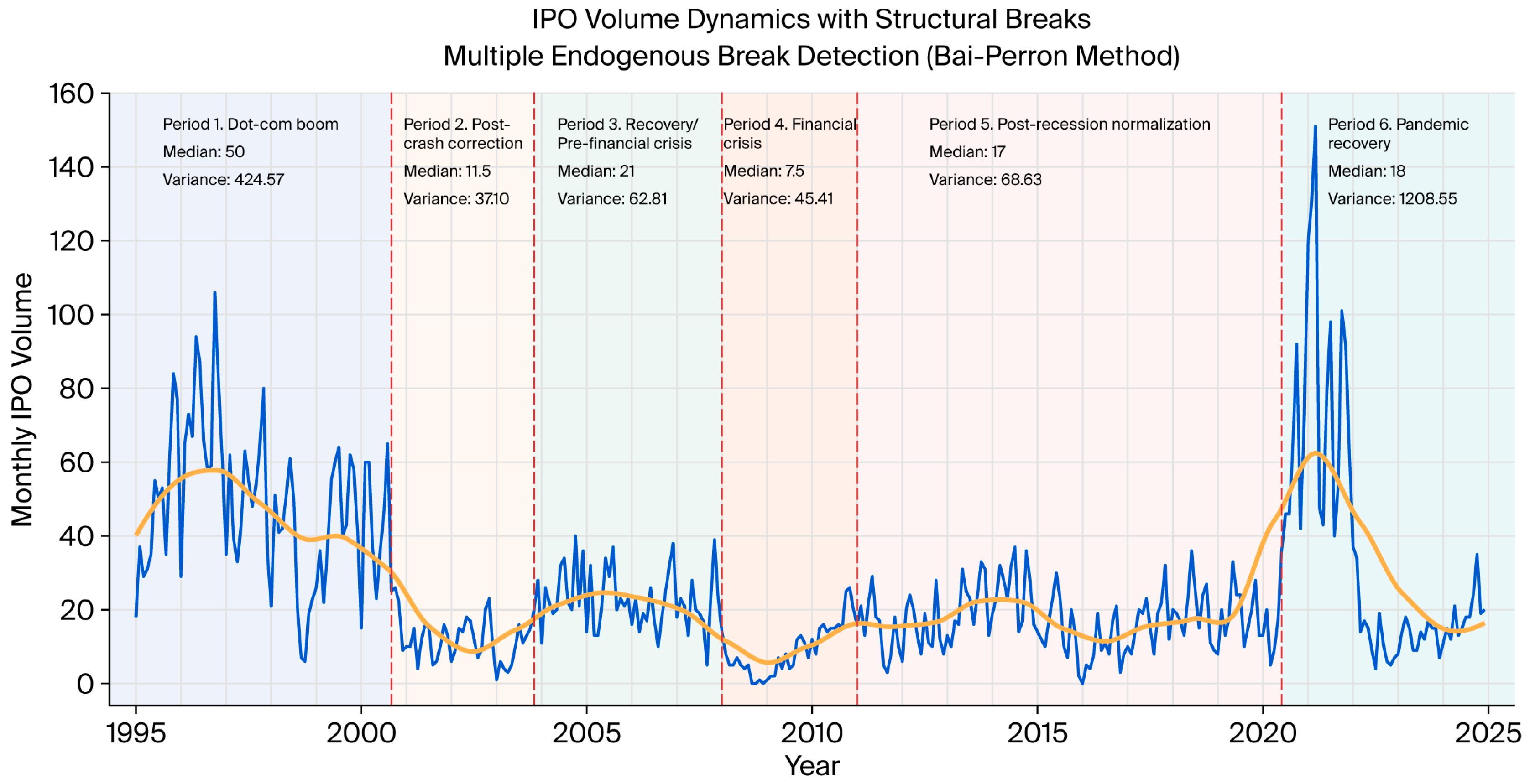

Our Bai-Perron analysis identifies structural shifts in the mean IPO rate through endogenous structural breaks, revealing the time-varying nature of IPO volume. The model identifies five structural breaks, corresponding to six distinct regimes of IPO activity. The economic significance of our endogenously identified breaks—coinciding with the dot-com crash, financial crisis, and pandemic—provides validation for the use of Bai-Perron for break detection, even in contexts involving count data of macroeconomic variables. Notably, the model identifies the pandemic-era break as May 2020, just two months after the World Health Organization declared the pandemic, demonstrating the method’s precision in detecting structural shifts. These periods include the dot-com boom (January 1995–August 2000), post-crash correction (September 2000–October 2003), recovery period/pre-financial crisis (November 2003–December 2007), financial crisis (January 2008–December 2010), post-recession normalization/pandemic onset (January 2011–May 2020), and pandemic recovery with inflation management (June 2020–December 2024).

Table 2 presents the Bai-Perron breakpoint test results, confirming all identified breaks are statistically significant at the 1% level.

As in

Herley et al. (

2023), we examine how variance and median IPO volumes differ across structural breaks (

Table 3). The variance in IPO volume is dramatic across regimes, ranging from 37.1 in the post-dot-com crash period from September 2000 to October 2003 to 1208.5 during the more recent period from June 2020 to December 2024, representing a 32-fold difference. Most strikingly, Period 6’s variance-to-mean ratio of 33.74 dwarfs all previous periods (which ranged from 2.77 to 8.75), suggesting a fundamental shift in IPO market dynamics rather than a temporary shock. Median IPO volumes vary from 7.5 to 50 IPOs per month across regimes. The wide variance and median ranges indicate fundamental instability in IPO activity, supporting the endogenous structural framework of our research. Refer to

Table 3 and

Figure 1 for additional details.

Using Greene’s (

2008) framework, the negative binomial framework is specified as:

We extend

Greene’s (

2008) framework in Equation (5) by incorporating endogenous structural breaks identified through Bai-Perron multiple breakpoint regression testing. The time-varying nature of IPOs is captured in our negative binomial regression model by indicator variables

–

, with Period 1 (January 1995–August 2000) serving as the baseline captured in the intercept:

Upon inspection, our IPO data exhibit severe overdispersion with an overall variance-to-mean ratio of 19.27 (see

Table 3), which violates the equidispersion assumption of a Poisson regression. Formal testing using the likelihood-ratio (LR) statistic, where our null hypothesis is

and our alternative hypothesis is

confirms this with an LR statistic of 153.92 and a

p < 0.001 (see

Table 4). The overdispersion is also evident across all time periods, with the variance-to-mean ratio ranging from 2.77 to 33.74, further underscoring the need to use a negative binomial regression approach for modeling IPO volume.

While Markov-switching models have been applied to IPO research assuming recurring hot and cold dynamics, our identification of six distinct regimes makes such approaches infeasible. A two-state Markov-switching specification, although estimable, cannot accommodate the six distinct regimes identified by our structural break analysis. Our Bai-Perron approach, which utilizes fixed regime indicators, offers a practical alternative that accommodates non-recurring structural changes. The proportion of months with zero IPOs is low (4 months, 1.1%), indicating that a standard negative binomial regression model can adequately accommodate them. Zero-inflated specifications address excess zeros beyond what a count distribution predicts; with only 1.1% zeros, such complexity is unwarranted. As

Cohn et al. (

2022) note, zero-inflated models are suitable when data exhibit excessive zeros, but identifying factors that affect exposure can be challenging.

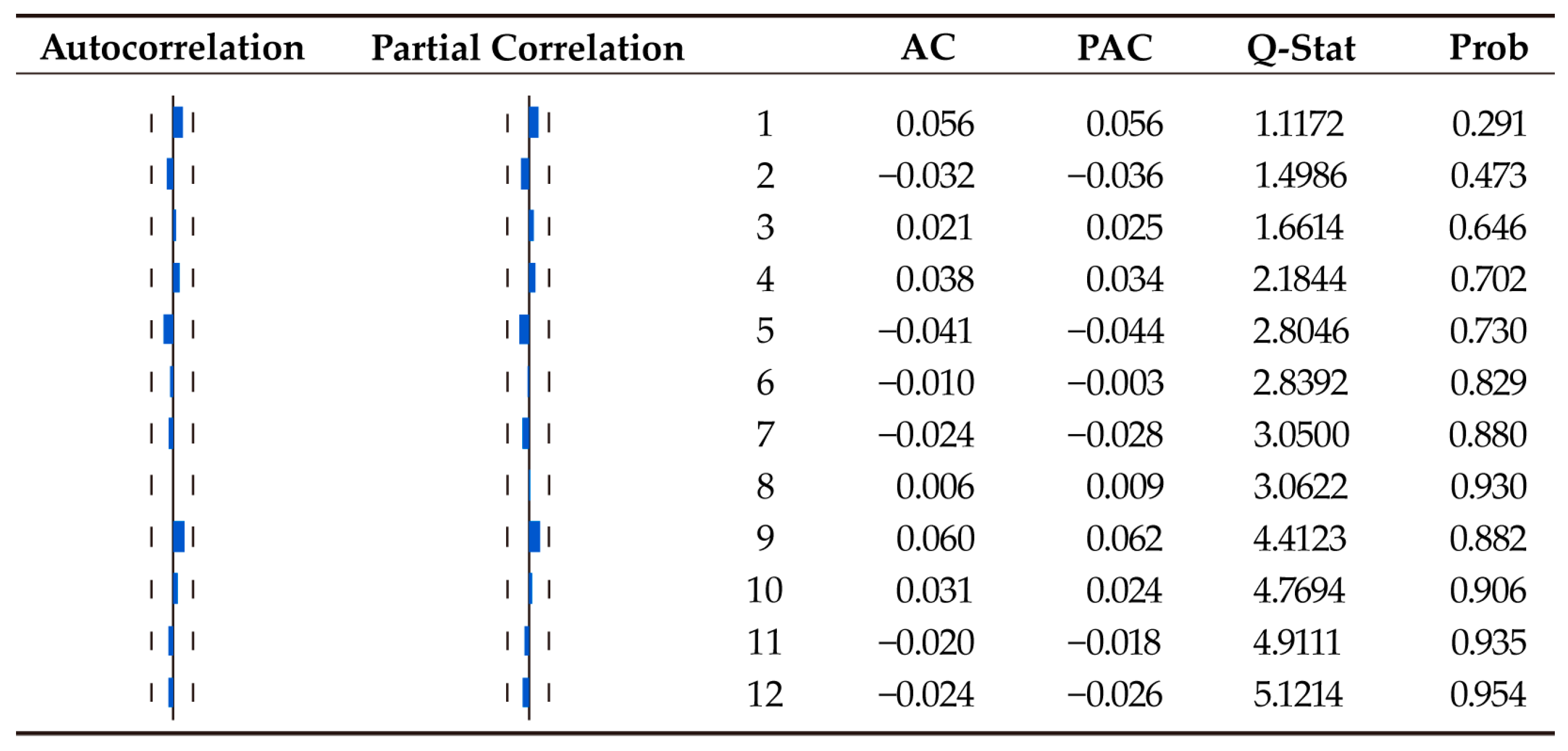

All variables, including the constant (which represents the baseline IPO activity), are statistically significant at the 1% level, except for DGS10, which is significant at the 5% level. Tests on squared residuals confirm the absence of heteroskedasticity or ARCH effects (maximum autocorrelation = 0.060, all

p-values > 0.29). Standard serial correlation diagnostics are less reliable for count model residuals, though the absence of patterns in squared residuals suggests adequate model specification. See

Figure A1 in

Appendix A.

Our regression coefficients are logarithmic; accordingly, we exponentiate them into count effects for economic interpretation. For example, with β1 = 0.017, we have exp(0.017) = 1.017. A practical interpretation of the coefficient is that each additional IPO in the previous month increases expected current IPOs by 1.7% (holding all other variables constant). Each one-point increase in VIX reduces expected IPOs by 3.7%, corroborating that market uncertainty deters or tempers IPO activity. Each one percentage point increase in 10-year Treasury rates reduces expected IPOs by 17.1%, reflecting the significant impact of financing costs on IPO decisions.

The post-crash correction period (D2) has 58.2% fewer IPOs than our baseline. The recovery period/pre-financial crisis period (D3) has 55.8% fewer IPOs. The financial crisis period (D4) has 75.1% fewer IPOs than the baseline, consistent with the frozen capital markets that followed Lehman’s collapse. The post-recession normalization/pandemic onset period (D5) has 74.7% fewer IPOs than the baseline. The pandemic recovery with the inflation management period (D6) has 62.3% fewer IPOs than the baseline. The constant represents the Period 1 baseline, which had the highest median IPO volume (50) and sustained high activity. All subsequent periods show significant reductions from this baseline (55.8–75.1%), indicating that the consistent high volume of the dot-com era was a historical anomaly.

To examine whether overdispersion varies across regimes, we estimate separate negative binomial models for each regime.

Table 5 presents the likelihood ratio tests for overdispersion across all six regimes.

Pre-crisis periods (Zones 1–3) exhibit no statistically significant overdispersion, as indicated by LR statistics that fail to reject the Poisson null. The 2008 financial crisis marks a structural shift: Zone 4 is the first period where overdispersion becomes statistically significant (LR = 19.19, p = 0.014). Notably, Zone 5 (post-recession normalization) exhibits no significant overdispersion (p = 0.38), suggesting that markets stabilized during this period. Post-May 2020, overdispersion returns with unprecedented intensity (LR = 33.40, p < 0.001). The negative binomial specification remains appropriate throughout, as it nests the Poisson distribution, yielding efficient estimates when overdispersion is minimal while accommodating the extreme variance observed in later periods.

The importance of our structural break specification is further illustrated by examining S&P 500 returns. In a baseline OLS model, log returns appear significant (β = 54.03, p = 0.035). However, this relationship becomes insignificant (β = 1.02, p = 0.430) in our structural break-adjusted negative binomial model, suggesting the apparent relationship reflects both variables responding to the same economic shifts rather than market returns directly driving IPO activity.

Robustness

We test whether our results hold with alternative specifications. Including a second lag IPO (−2) and Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) alongside our original variables, all structural breaks remain significant at the 1% level. The second lag is significant (p < 0.001), and EPU is marginally significant (p = 0.074). Our core finding remains: structural breaks identify distinct IPO regimes regardless of the specification used.

We also examine potential endogeneity concerns.

Table A1 in

Appendix A presents results using lagged values of VIX and DGS10. The results remain virtually unchanged, with both market uncertainty and financing costs continuing to have negative and statistically significant effects on IPO activity. The stability of coefficients across specifications (VIX: −0.031 vs. −0.038; DGS10: −0.193 vs. −0.187) confirms that our findings are robust to concerns about endogeneity.

To test whether our structural breaks capture autoregressive dynamics rather than genuine structural changes, we re-estimated the Bai-Perron model including three lags of IPO volume.

Table A2 presents the results. Early regimes show remarkable stability: Regime 1 remains stable, Regime 2 is identical across specifications, and Regime 3 shifts by only two months. The middle regimes (4–5) exhibit greater sensitivity to lag inclusion, reflecting the complex post-crisis dynamics of this period. Specifically, the lag-augmented model merges the 2008–2010 financial crisis with the subsequent post-Dodd–Frank normalization period into a single regime (2007M11–2018M04), obscuring a key structural distinction in IPO market conditions. Importantly, a distinct post-2020 regime persists across specifications, confirming that our core finding—the unprecedented overdispersion in recent years—is robust to model specification. We retain the original specification because its regime boundaries align with identifiable economic events (the dot-com crash, the financial crisis onset in January 2008, the post-crisis normalization beginning January 2011, and the pandemic), enhancing practical applicability.

Finally, to address concerns about the two-step procedure, we test for structural breaks in the residuals of the negative binomial model. The Bai-Perron test finds no significant breaks, confirming that our zone independent variables adequately capture the structural shifts.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to apply Bai-Perron breakpoint regression tests to financial count data, demonstrating that U.S. IPO volume dynamics necessitate the identification of multiple structural breaks and the use of proper count methods that account for overdispersion. The 32-fold variance increase across regimes post-dot-com (from 37.1 to 1208.5), coupled with persistent overdispersion, reveals instability in market structure that neither traditional OLS models nor two-state regime-switching approaches can adequately capture. Regime-specific likelihood ratio tests reveal that statistically significant overdispersion first emerges with the 2008 financial crisis (LR = 19.19, p = 0.014), subsides during the post-recession normalization period (p = 0.38), and returns with unprecedented intensity after May 2020 (LR = 33.40, p < 0.001). This suggests the financial crisis disrupted IPO market dynamics; markets partially healed during the subsequent decade, but the pandemic shattered this stability, creating the most volatile IPO environment in our sample.

The failure of IPO volumes to recover to their dot-com era baseline across multiple market cycles suggests that structural breaks represent permanent regime changes, not temporary shocks. The shift to higher variance regimes suggests that standard IPO timing models may require reconsideration. A baseline OLS specification without structural breaks yields a positive coefficient on DGS10 (+3.05,

p < 0.001), implying that higher interest rates increase IPO activity—directly contradicting financial theory. This sign reversal is consistent with

Cohn et al.’s (

2022) finding that log-linear approaches can produce wrong-signed coefficients when applied to count data. After accounting for structural breaks, the coefficient reverses to −0.187 (

p < 0.05), aligning with corporate finance theory.

Our methodology provides policymakers and practitioners with more accurate tools for monitoring IPO market health and timing market entry, as traditional methods often mask critical regime changes or employ a limited hot and cold approach. The identification of six distinct regimes—with statistically significant overdispersion emerging in 2008 and returning with unprecedented intensity after May 2020—suggests that IPO timing strategies based on pre-crisis patterns may no longer be applicable. Future research might examine whether similar patterns exist in other capital markets.