The Impact of Philanthropic Donations on Corporate Future Stock Returns Under the Sustainable Development Philosophy—From the Perspective of ESG Rating Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Analysis

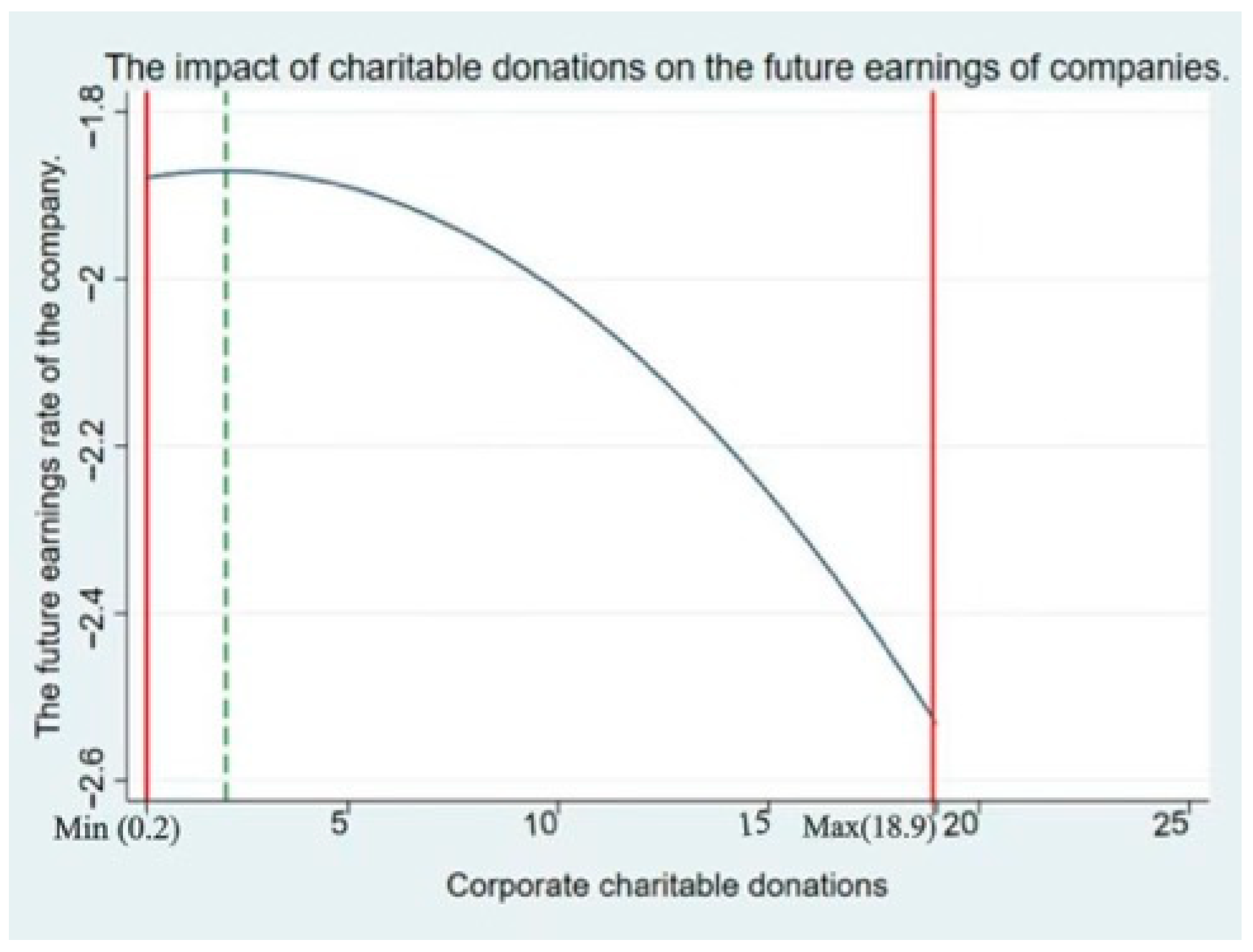

2.1. The Impact of Charitable Donations on Future Corporate Returns

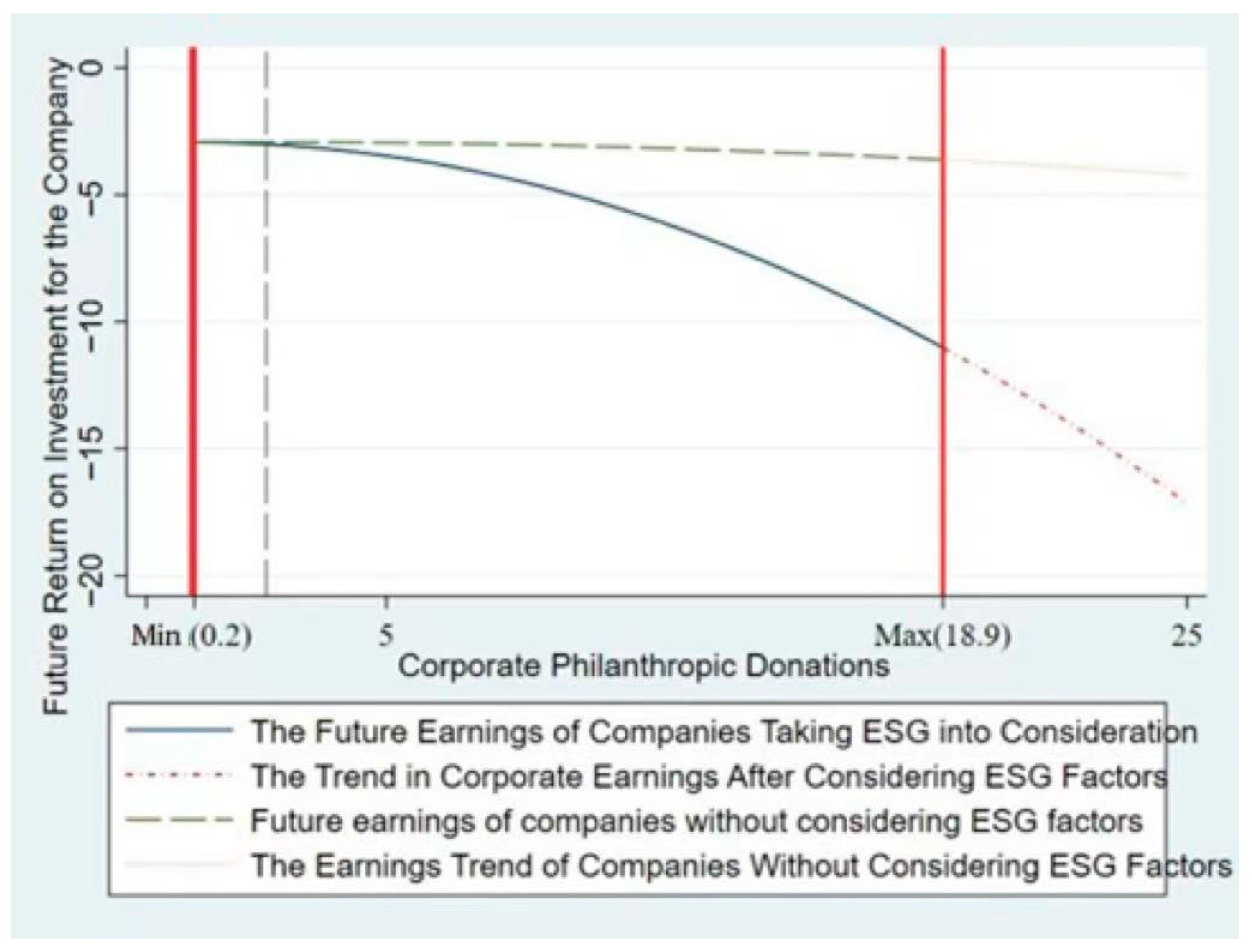

2.2. ESG Rating Constraints Accelerate the Diminishing Effect of Charitable Donations on Future Corporate Returns

3. Data Sources and Features

3.1. Data Sources and Model Design

3.1.1. Data Sources

3.1.2. Model Design

3.2. Variable Definitions

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Lagged Regression

4.4.2. Change in Future Returns Measurement

4.4.3. Change in ESG Measurement

4.4.4. Consideration of Outliers

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Heterogeneity in Ownership

4.5.2. Lifecycle Heterogeneity

4.5.3. Heterogeneity in Industry Competitiveness

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, R., & Audretsch, D. B. (2001). Does entry size matter? The impact of the life cycle and technology on firm survival. Journal of Industrial Economics, 49(1), 21–43. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=cP5JN5wNT8BtTf9op47C1IZLMiqjPB3D9yu0xpEQfEwDRyxkI1B57nfQgmj_cCsGDuEQM_YTiZhbNnDDZsYOyDfjpWO3AZ3mVwPZxLF0lBAwNBXTIm8gD_9n7tN6YHAIPWLqpiYE8BX0McMJAEgiCc28I2BHlssC0111YU6ZQrHYKt6Slf8WhzRiYSHqqLkY&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27(11), 1101–1122. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPn9XRSnJaqFk0bQUU58e7Ty-wEKQc1P-1k2CTOJVAwK-rCLlIQbNwkzINSz3DIFcXDggpjTUcEgdHQdGEXJeyON515I4GeMYETvGZXE-ty7D9SKk7YPiYurKCWSF9GES0FnJT7d-N1WuphmmM441Ox2vsWYV5q6qJx8KrgzVN0w4mbJOXaPLi2V&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barth, F., Hübel, B., & Scholz, H. (2022). ESG and corporate credit spreads. Journal of Risk Finance, 23(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H. M., & Meng, Y. (2019). Is corporate charitable donation hypocritical? A study based on the perspective of stock price crash risk. Accounting Research, (04), 89–96. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPmBIIETdyRW_63WuoQ0pRhS2g_68Bde2tDcOkTaK5xDeUxG3cXpqZh6mNiQP7vJVgMUVtTfBRqzblRu9IhMM08LjyhD7TsEjUfRQqEecYz7xxJtv2slozyWE2fh9DTxrY___VUSQ-caWVqjqdNmWK4J2Zsr79tykdZpyfhnzjPI2w==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chen, L., Yang, Y., & Wu, Y. (2023). The social catalyst of “good begets good”: The role of media reporting in enhancing corporate performance through charitable donations. Western Forum, 3, 50–63. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/50.1200.C.20230703.1704.002 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Chen, X. Y. (2025). Regulatory dilemmas and optimization paths of ESG regulation in China. Jianghuai Forum, (02), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Pan, Y., & Feng, S. (2014). Are corporate charitable donations “political contributions” in China? Evidence from changes in municipal party secretaries. Economic Research, 49(2), 74–86. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPm3fqGg9Qt3GGK9KL0ILjtas7U154oi67NgolYBkkOEP--V42_O5F0focZSqNzCvJfs50-U94pgf6aWbOAOy21n1zOj6lfYcKeAnktzbAKwSOl__KyYYIV07hOMwRXupcBc4yLSQ1emSTV3uxyVr3EFa5IiH42RSSAqot9-U6Vqrh27wD4WxG49&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Fang, X. M., & Hu, D. (2023). Corporate ESG performance and innovation: Evidence from A-share listed companies. Economic Research Journal, 58(02), 91–106. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPl3etSC7p9r0PRAJzH5cFwAXnZjZZ95JWtkKvGaXW_XEc7p8nudiYZvLtJWOOmfT7hmvltEa8RPbooJenV_C6xKGyV6eCmug84UXsD2YBTxgywELf6sITCgeOjZjUJ-vPRgbQXOQOrofXdOVh887ZjpUHvAk0wVzQmpTUOsEu5ENw_0NxpKD8v-&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Fombrun, C. J., & Gardberg, N. (2000). Who’s tops in corporate reputation? Corporate Reputation Review, 3(1), 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Chu, D., Lian, Y., & Zheng, J. (2021). Can ESG performance improve corporate investment efficiency? Securities Market Herald, 11, 24–34+72. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/44.1343.F.20211028.1139.004 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Gao, Y. Q., Chen, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2012). “Red scarf” or “green scarf”: A study on the motivation of charitable donations by private enterprises. Management World, 8, 106–114+146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S. L., Koch, A., & Starks, T. (2021). Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPn7wQ8JTFzmIxd6cTA4uVXRugK59GfEzpv5AK3_eNZviN2I7awgvyZTIcTiOmrmOuIYR2hLwTwMF31IWWPTx-pQZG9HAHvTK9Uqk4s1BZroN8Z4alyGCVOraUIh1uBk_egJE_FtEvaJj7sl6hNVcL1i9FoNeewcLzxQ7PDPnnPPtj1lv-XiRoUwemkEGDwxel-bvNsw4s27ag==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gu, L., & Peng, Y. (2022). The impact of charitable donations on corporate performance: The moderating effect of corporate lifecycle. Management Review, 3, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. C., Fu, X. R., & Li, P. C. (2024). Top managers’ cognition, open innovation, and enterprise digital transformation: An empirical study based on high-tech enterprises. Scientific Management Research, 42(03), 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F., Shen, Y., & Cai, X. (2020). Corporate governance effects of multiple large shareholders: A perspective from controlling shareholders equity pledges. World Economy, 2, 74–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., & Yu, J. (2021). The role and mechanism of the third distribution in promoting common prosperity. Zhejiang Social Science, 9, 76–83+157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., & Huang, S. (2022). From CSR to ESG: Evolution, literature review, and future prospects. Financial Research, 4, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. L., Hou, X. T., & Ge, C. F. (2017). Is charitable donation genuine or hypocritical? Perspective of corporate violations. Journal of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 4, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Y., Lin, Z. F., & Leng, Z. P. (2020). Does tax incentive increase corporate innovation? An empirical test based on the theory of corporate lifecycle. Economic Research, 55(6), 105–121. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPnFjFgvs6VOBhwAjbaDIHoGgecJHI2XoiHTfK_sNQAMsYDH9tjwcHjl5sLcktNF_w4dAMJChwPCPQzac9DtAuiBVDTQcDYdbSPq82G5vyjehed-AaIFSjDTqRWdJucfjd6f7ylbs1Ke4REwDO8vGP2AXnWO2TR9vNnrCT6y8U3lKckIih9z-vA0&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Liu, Y., & Yin, J. (2020). Stakeholder relationships and organizational resilience. Management and Organization Review, 16(5), 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q., Zhu, Y. M., & Lin, F. (2015). The optimal donation strategy of state-owned enterprises in a dilemma: Empirical findings based on the differences in property rights donations and their performance. China Industrial Economics, 9, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, B., Gold, A., & Gold, S. (2022). ESG disclosure and idiosyncratic risk in initial public offerings. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(3), 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y., Lv, M. H., & Xu, G. H. (2020). Charitable donations, corporate governance, and investment-cash flow sensitivity of listed companies. Management World, 17(2), 269–277. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=cP5JN5wNT8DtrCDKZYrb_DzTqLqqoDerlr8LUxdnMqE-LuVZXjtWX7rtyky3wNlDqnzQONPE_vDtSmPDhutsNOp5GmbwFY7nql_xU1v5LvEBYKFF7ShA5dXUVxXDhVf1TMkgPm9MYiWCZpftCayRR4tmo8NNnMY0BFuArx6Y0MveF65ozuDO5A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Song, K., Xu, L., & Li, Z. (2022). Can ESG investment promote banks to create liquidity? Dual effects of economic policy uncertainty. Financial Research, 2, 61–79. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPnHtDEUtwAasz3MwipjJ-4sTcKGfsZw0XvJOtS0G7i5-em5G5Oyl0FayzY2CxhIOOXltgT2JXIb5uRqA1-Mq7l8vdz0wCNXOftZSIqqmEHpXZtHlTETb1BAvmgp1CuNh7RMZuhZpSqvQ_d3Ldvk8GztLwZD2PdGpndt86MBqoI8QZPlHoc98eUV&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Song, Q. H., Zhou, X. Q., & Deng, X. (2023). ESG ratings and corporate environmental investment: Incentives or concealment? Financial Forum, 11, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. L., & Liu, X. (2022). Can corporate charitable donations get value returns? Dual perspectives on technological innovation and financial constraints. Journal of Hunan University of Technology (Social Science Edition), 27(4), 49–58. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPmDPn2FUcsRTGDWJdDmKfFI6HTkqPwpMYLCRyo6z_XZE1yXDlvCOCMD5uG210TVp7jRMkG8iHcejSrhnHoyae1AfCs8RYOVKVq6SkUU-5dk28UQu3V_xKTfRnCebkCO_Gkd_QzZzSRrrGb1EV-coQt5ZtSnlkUxS4INWqESSdp4Ow==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Wang, H., Choi, J., & Li, J. (2008). Too little or too much? Untangling the relationship between corporate philanthropy and firm financial performance. Organization Science, 19(1), 143–159. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPmNly_dUCpSSooWq5BcNV4hxjAtVB0-y72LSBRmyzd1p6qL8BIcgvcWM_AbIzfid4ox6lX0QdkfJ6pHq7Kl9ejONEOW9cgB0m8BvRmIszmT55pN7AJVwEGls5Iw9jzICFNfz7358EQFcYd6FbSCXviE2UzjbNan1-ER7scBOEOb4izj8O5by1Ok&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Liu, J. T., & Ge, M. (2023). Analysis and future development of China’s ESG ratings. Academic Exploration, 8, 67–78. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPl9Qn3IgOHNGZZrk-AVmYgNH7eo0yy42adDvN5MIoZXkIrbx3NnN2MkCiLQh_iknpFxfH1du11qEmgbc-8tAs4ICIb0FkGxyqN5lUmtMpLdeIdoqay74FXLI6uQ87TTKvjwG9dQWqv4WhqtWRG9ZUV1UZt7xnLe4iMqcFFjkofzQw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Wei, G. X. (2005). A review and brief comment on the theory of enterprise life cycle. Productivity Research, (06), 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P., Yang, K., Jiang, J. S., & Wang, H. (2023). Does corporate ESG performance affect the relevance of earnings-value? Financial Research, 6, 137–152+169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, W. D., & He, Q. (2005). A brief analysis of factors affecting corporate value. Finance and Accounting Monthly, 26, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. H., Shi, H. R., & Qin, Y. Z. (2019). The impact of the gap between internal and external corporate social responsibility on corporate value. Journal of Hunan University (Social Science Edition), 6, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., & Li, M. Y. (2021). The impact of major shareholders’ shareholding levels on open market repurchases: Mutual maintenance or mutual harm? Southern Finance, 3, 61–75. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/44.1479.F.20210518.1647.002 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Yan, W. X., Zhao, Y., & Meng, D. F. (2023). Research on the impact of ESG ratings on the financial performance of listed companies. Journal of Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, 6, 71–80. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1867.F.20231109.1050.008 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Yuan, Z. M., & Wang, P. L. (2021). Did the contagion effect of negative events affect the donations of affected companies? Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, 2, 17–27+158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Fu, L. H., & Zheng, B. H. (2018). Motivation for charitable donations by listed companies: Altruistic or selfish? Empirical evidence based on the earnings management of Chinese listed companies. Audit and Economic Research, 2, 69–80. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1317.F.20180206.2243.010 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Zhang, C. N. (2023). The impact of innovation investment on the future stock returns of listed companies [Master’s thesis, Northeastern University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. M. (2025). How open public data stimulates the vitality of the private economy: From the perspective of private investment. Modern Economic Research, (12), 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Ma, L. J., & Zhang, W. (2013). The political and corporate tie effect of corporate charitable donations: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Management World, 7, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. L. (2016). The “Charity Law” and the sustainable development of charity in China. Jianghuai Forum, 4, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. G., Li, Y. J., & Li, L. (2016). Research on the relationship between corporate charitable donations, acquisition of technological resources, and innovation performance: Based on the perspective of resource exchange between enterprises and governments. Nankai Management Review, 19(3), 123–135. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPmYOoczNPwAQInTJm1zflvVHWtOPB99wBJj2XN0_7lGT69H1loWNcu6lDeC5aXSi64oa-v5LCRJslNKfRSGhkdsU7f33LJArnncwZ3akSxTodGxvHEtcqm43aafktAyrTCL_kRjKcw3XVB1vDGqnUuVJZLcH2HBdseTw3jvibfeyw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Zhao, W. H., Ren, Y. Y., Zhang, L., & Liu, J. L. (2025). The impact of digitalization level of entrepreneurial enterprises on innovation performance. Studies in Science of Science, 43(5), 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. M., Chang, M. K., & Zhang, S. C. (2019). Charitable donations, government-business relationships, and corporate value. Accounting Friends, 4, 66–71. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/14.1063.f.20190123.1514.026 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Zou, P. (2019). Research on the dynamic adjustment mechanism and heterogeneity of charitable donations. Management Journal, 16(6), 904–914. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=A8ynNhXZdPnBkc58rRPOGP6d3lXYeH6RveBv3VcoJKpUHN7Hv4vZK_YjqTt6ohDUBq-5pF71lxmISJ1TiU-7ks1m-lcyhTu2yE-ZW_sLreDIgdvIhXHZ2EYjoW1n6N_2fBozP2apA5f9U4e6HhC1ecaP8PptytD8tNVH2F7pc67ubY0vhOn18A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 18 November 2025).

| Variable Names | Variable Symbols | Unit | Measurement Methods of Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm’s Future Return Rate | RET | % | Annual stock return rate considering cash dividends reinvestment—Annual risk-free interest rate |

| Corporate Charitable Donations | Dona | _ | Logarithm of the sum of donation amounts disclosed in social responsibility reports + 1 |

| ESG Constraints | Dona2 ESG | _ | Square of Dona Huazheng rating data (scaled from 1 to 100 points) |

| Book-to-Market Ratio | BTM | _ | Total assets/Total market value |

| Turnover Rate | Turn | % | Sum of daily turnover rates within the year |

| Firm Size | Size | _ | Logarithm of the total assets of the firm |

| Profitability | Roa | % | Net profit/Total assets |

| Shareholding Ratio of Major | LR | % | Sum of the shareholding ratios of the top ten shareholders |

| Shareholders Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Lev | % | Total liabilities/Total assets |

| Corporate Age | Age | _ | Observation year (current statistical cutoff date)—IPO year |

| Ownership Nature | State | _ | Dummy variable, takes the value of 1 for state-owned enterprises, and 0 otherwise |

| Board Size | Board | _ | Logarithm of the sum of the number of directors on the board + 1 |

| Ownership Concentration | Dttoprc | _ | Total liabilities/Total equity |

| Cash Flow | Cash | _ | Net cash flow from operating activities/Closing stock price on the last trading day of the year |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RET | 2625 | −2.2985 | 0.7087 | −3.8127 | 1.4813 |

| Dona | 2625 | 4.8272 | 2.0666 | 0.1823 | 18.9154 |

| Dona2 | 2625 | 0.1046 | 5.2505 | 0.0000 | 268.9600 |

| ESG | 2625 | 75.5461 | 5.7590 | 36.6200 | 91.4600 |

| BTM | 2625 | 0.6733 | 0.2834 | 0.0448 | 1.5592 |

| Turn | 2625 | 554.3063 | 534.8639 | 7.2479 | 8028.7980 |

| Size | 2625 | 4.5686 | 17.8550 | 0.0364 | 273.3190 |

| Roa | 2625 | 0.0489 | 0.0826 | −1.3584 | 0.7859 |

| LR | 2625 | 60.6766 | 15.0140 | 15.9300 | 97.9300 |

| Lev | 2625 | 0.4293 | 0.1929 | 0.0143 | 0.9886 |

| Age | 2625 | 11.0419 | 8.0858 | 1.0000 | 30.0000 |

| State | 2625 | 0.3029 | 0.4596 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Board | 2625 | 2.2368 | 0.1780 | 1.6094 | 2.9444 |

| Dttoprc | 2625 | 1.1187 | 2.1586 | 0.0145 | 86.7639 |

| Cash | 2625 | 2.8118 | 15.7662 | −23.1597 | 359.6100 |

| Variable | Dona | Dona2 | BTM | Turn | Size | Roa | LR | Lev | Age | State | Board | Dttoprc | Cash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dona | 1.0000 | ||||||||||||

| Dona2 | 0.1354 *** | 1.0000 | |||||||||||

| BTM | 0.1386 *** | −0.009 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| Turn | −0.2032 *** | −0.019 | −0.2543 *** | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| Size | 0.3264 *** | 0.0270 | 0.2769 *** | −0.1623 *** | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| Roa | 0.1066 *** | 0.0060 | −0.2639 *** | 0.0300 | −0.0444 ** | 1.0000 | |||||||

| LR | 0.1399 *** | 0.0353 * | 0.0200 | −0.0835 *** | 0.1911 *** | 0.1277 *** | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Lev | 0.1996 *** | 0.0060 | 0.4393 *** | −0.1869 *** | 0.2529 *** | −0.2866 *** | 0.0170 | 1.0000 | |||||

| Age | 0.1967 *** | 0.0120 | 0.3572 *** | −0.3609 *** | 0.1284 *** | −0.1324 *** | −0.2457 *** | 0.3407 *** | 1.0000 | ||||

| State | 0.1169 *** | 0.0290 | 0.3553 *** | −0.2499 *** | 0.2485 *** | −0.0862 *** | 0.0887 *** | 0.2793 *** | 0.4674 *** | 1.0000 | |||

| Board | 0.1373 *** | 0.0589 *** | 0.1666 *** | −0.1423 *** | 0.0847 *** | −0.0060 | 0.0050 | 0.0982 *** | 0.1914 *** | 0.2526 *** | 1.0000 | ||

| Dttoprc | 0.0538 *** | −0.0010 | 0.2087 *** | −0.0741 *** | 0.1382 *** | −0.1970 *** | 0.0140 | 0.5025 *** | 0.1469 *** | 0.1286 *** | −0.0010 | 1.0000 | |

| Cash | 0.2284 *** | 0.0417 ** | 0.1669 *** | −0.1128 *** | 0.7141 *** | 0.0070 | 0.1754 *** | 0.0874 *** | 0.0797 *** | 0.1698 *** | 0.1207 *** | 0.0300 | 1.0000 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RET | Dona | RET | |

| ESG | −0.7990 *** | ||

| (−3.0993) | |||

| Dona | 0.0096 ** | −0.0318 | |

| (2.1145) | (−0.8681) | ||

| Dona2 | −0.0023 *** | 0.0019 | |

| (−7.9006) | (0.6655) | ||

| ESG × Dona | 0.0009 * | ||

| (1.8638) | |||

| ESG × Dona2 | −0.0006 *** | ||

| (−2.6188) | |||

| BTM | −0.9186 *** | −494.5209 | −1.1609 *** |

| (−18.5844) | (−0.6202) | (−22.2923) | |

| Turn | 0.0001 *** | −0.1725 | 0.0002 *** |

| (4.9240) | (−1.1286) | (8.8586) | |

| Size | 0.0003 | 77.0650 ** | 0.0012 |

| (0.5592) | (2.2879) | (1.1551) | |

| Roa | 0.7755 *** | 458.4335 | 0.7823 *** |

| (6.6512) | (0.1831) | (4.6369) | |

| LR | −0.0009 | 9.4070 | −0.0011 |

| (−1.3404) | (0.9388) | (−1.2776) | |

| Lev | 0.5800 *** | −684.3735 | 0.6354 *** |

| (9.0728) | (−0.4716) | (7.5811) | |

| Age | 0.0043 *** | 23.3792 | 0.0085 *** |

| (3.0490) | (1.0892) | (4.2833) | |

| State | 0.0302 | −701.7180 | 0.0006 |

| (1.4655) | (−1.5962) | (0.0186) | |

| Board | −0.0840 * | 1187.9887 | −0.1559 ** |

| (−1.7040) | (1.3956) | (−2.1768) | |

| Dttoprc | −0.0106 *** | 267.7730 | −0.0221 *** |

| (−2.8923) | (1.0374) | (−3.3922) | |

| Cash | 0.0016 ** | 136.8017 | 0.0017 |

| (2.0687) | (1.5941) | (1.5115) | |

| Constant | −1.8804 *** | −80.9692 *** | −1.7756 *** |

| (−15.6346) | (−2.6585) | (−10.2283) | |

| Sample size | 2625 | 2622 | 2622 |

| R-squared | 0.667 | 0.125 | 0.240 |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES |

| F-value | 40.05 | 4.281 | 54.86 |

| Variables | Lagged One Period Explanatory Variables | Change in Measurement Approach for Dependent Variable | Replacement of ESG with Imputation Method | Consideration of Outliers’ Influence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| RET | RET | TobinQ | TobinQ | RET | RET | RET | RET | |

| LDona | −0.0024 | 0.0234 * | 0.0333 *** | 0.0304 ** | 0.0096 ** | 0.0250 ** | 0.0082 * | 0.0256 ** |

| (−0.3874) | (1.7140) | (3.3438) | (2.5259) | (2.1145) | (2.0642) | (1.9027) | (2.1128) | |

| LDona2 | −0.0013 *** | −0.0007 | −0.0067 *** | −0.0009 | −0.0023 *** | −0.0063 *** | −0.0024 *** | −0.0062 *** |

| (−3.7054) | (−0.3045) | (−9.1979) | (−0.5499) | (−7.9006) | (−8.3739) | (−8.3430) | (−8.4351) | |

| LDona × ESG | 0.0058 * | 0.0052 ** | 0.1323 ** | 0.0052 ** | ||||

| (1.7665) | (2.5581) | (2.4535) | (2.4471) | |||||

| LDona2 × ESG | −0.0011 ** | −0.0011 *** | −0.0247 ** | −0.0011 ** | ||||

| (−2.2957) | (−3.7300) | (−2.1159) | (−2.3321) | |||||

| BTM | −0.7519 *** | −4.3858 *** | −4.5707 *** | −4.5716 *** | −0.9186 *** | −4.5681 *** | −0.8763 *** | −4.5704 *** |

| (−12.9887) | (−27.0763) | (−28.8620) | (−29.3617) | (−18.5844) | (−29.3468) | (−19.7721) | (−29.2620) | |

| Turn | 0.0003 *** | −0.0002 *** | −0.0002 *** | −0.0002 *** | 0.0001 *** | −0.0002 *** | 0.0001 *** | −0.0002 *** |

| (8.4614) | (−4.6127) | (−5.1098) | (−5.1176) | (4.9240) | (−5.1420) | (5.2330) | (−5.1266) | |

| Size | 0.0008 * | 0.0028 *** | 0.0018 | 0.0019 * | 0.0003 | 0.0019 | 0.0003 | 0.0019 |

| (1.7280) | (2.9980) | (1.4648) | (1.7097) | (0.5592) | (1.5494) | (0.6683) | (1.5945) | |

| Roa | 1.7474 ** | 1.5530 *** | 1.4049 *** | 1.6051 *** | 0.7755 *** | 1.6104 *** | 0.9656 *** | 1.5932 *** |

| (2.3866) | (3.1456) | (3.1872) | (3.8471) | (6.6512) | (3.8804) | (7.8873) | (3.7881) | |

| LR | −0.0001 | −0.0007 | −0.0003 | −0.0002 | −0.0009 | −0.0001 | −0.0012 ** | −0.0002 |

| (−0.1461) | (−0.4565) | (−0.2179) | (−0.1205) | (−1.3404) | (−0.1025) | (−1.9881) | (−0.1320) | |

| Lev | 0.5129 *** | −0.3741 * | −0.3360 * | −0.3584 * | 0.5800 *** | −0.3591 * | 0.6369 *** | −0.3571 * |

| (5.2196) | (−1.9611) | (−1.7963) | (−1.9358) | (9.0728) | (−1.9390) | (7.8423) | (−1.9252) | |

| Age | 0.0060 *** | 0.0058 * | 0.0053 | 0.0048 | 0.0043 *** | 0.0049 | 0.0039 *** | 0.0048 |

| (4.1880) | (1.7744) | (1.5936) | (1.4227) | (3.0490) | (1.4430) | (3.0242) | (1.4362) | |

| State | 0.0519 ** | 0.1305 ** | 0.1081 * | 0.1270 ** | 0.0302 | 0.1235 ** | 0.0351 * | 0.1246 ** |

| (2.4239) | (2.2048) | (1.9318) | (2.2572) | (1.4655) | (2.1997) | (1.7918) | (2.2161) | |

| Board | −0.0668 | −0.2895 ** | −0.1629 | −0.1456 | −0.0840 * | −0.1541 | −0.0666 | −0.1545 |

| (−1.0716) | (−2.0183) | (−1.2369) | (−1.1282) | (−1.7040) | (−1.1893) | (−1.4497) | (−1.1926) | |

| Dttoprc | −0.0208 | 0.0497 ** | 0.0622 ** | 0.0622 ** | −0.0106 *** | 0.0633 ** | −0.0340 ** | 0.0633 ** |

| (−1.2783) | (2.1270) | (2.4508) | (2.5020) | (−2.8923) | (2.5343) | (−2.5369) | (2.5379) | |

| Cash | 0.0007 | 0.0076 | 0.0114 ** | 0.0098 * | 0.0016 ** | 0.0103 * | 0.0057 ** | 0.0103 * |

| (1.1024) | (1.5458) | (1.9881) | (1.7614) | (2.0687) | (1.8518) | (2.2526) | (1.8559) | |

| Constant | 0.3160 ** | 5.4842 *** | 5.2822 *** | 5.2537 *** | −1.8804 *** | 5.2906 *** | −1.9384 *** | 5.2935 *** |

| (2.2513) | (15.0083) | (15.5000) | (15.6885) | (−15.6346) | (15.7204) | (−16.6074) | (15.6832) | |

| Sample Size | 2339 | 2337 | 2625 | 2619 | 2625 | 2619 | 2625 | 2619 |

| R-squared | 0.293 | 0.724 | 0.705 | 0.708 | 0.667 | 0.707 | 0.693 | 0.707 |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F-value | 22.22 | 77.06 | 81.75 | 74.11 | 40.05 | 74.03 | 48.44 | 73.73 |

| Variables | State-Owned Enterprises | Nonstate-Owned Enterprises | Growth Stage | Mature Stage | Decline Stage | High Competition Level | Low Competition Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| RET | RET | RET | RET | RET | RET | RET | |

| Dona | 0.0587 *** | 0.0370 | 0.0318 | −0.0300 | 0.0162 | 0.0271 *** | 0.0308 *** |

| (2.6524) | (1.4567) | (0.7701) | (−1.3965) | (1.0595) | (2.6107) | (3.2110) | |

| Dona2 | 0.0007 | 0.0737 | −0.3250 ** | −0.3867 *** | 0.1413 ** | −0.0029 | −4.7710 |

| (0.3007) | (0.2762) | (−2.1621) | (−3.9880) | (2.3128) | (−0.9114) | (−1.1082) | |

| Dona × ESG | −0.0003 | 0.0116 * | 0.0016 | 0.0046 | −0.0014 | 0.0025 | 0.0048 *** |

| (−0.1096) | (1.7678) | (0.1840) | (1.4626) | (−0.6824) | (1.5893) | (3.1069) | |

| Dona2 × ESG | −0.0010 *** | −0.0018 | 0.0011 | 0.0015 *** | −0.0006 ** | −0.0001 | −0.0012 *** |

| (−2.9019) | (−1.3108) | (0.4111) | (3.8766) | (−2.0477) | (−0.3746) | (−3.5159) | |

| BTM | −3.8054 *** | −5.5795 *** | −0.5551 | −1.0451 *** | −1.0760 *** | −1.2875 *** | −0.8373 *** |

| (−10.1820) | (−20.7086) | (−1.2570) | (−3.8316) | (−7.0472) | (−17.3264) | (−12.9649) | |

| Turn | −0.0004 *** | −0.0002 *** | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 *** | 0.0002 *** | 0.0002 *** |

| (−3.8009) | (−3.9901) | (1.0809) | (0.5312) | (2.7572) | (6.8409) | (6.2116) | |

| Size | 0.0007 | 0.0135 * | 0.0535 ** | −0.0124 | 0.0002 | 0.0021 | 0.0010 |

| (0.8406) | (1.7467) | (2.3852) | (−0.6317) | (0.2638) | (0.7761) | (0.8075) | |

| Roa | 4.5933 *** | 0.8759 | 0.7092 | 1.1044 | 0.8626 ** | 0.8793 *** | 0.1633 |

| (3.4530) | (1.4627) | (1.2581) | (1.5868) | (2.5177) | (4.2508) | (0.5582) | |

| LR | −0.0009 | −0.0002 | −0.0060 | 0.0034 | −0.0012 | −0.0009 | 0.0002 |

| (−0.3363) | (−0.0904) | (−1.0626) | (0.6997) | (−0.5687) | (−0.6685) | (0.1302) | |

| Lev | 0.1218 | −0.3687 * | 0.8488 | −0.0068 | 0.6506 *** | 0.6791 *** | 0.1174 |

| (0.2981) | (−1.8996) | (0.8282) | (−0.0088) | (3.5660) | (6.1017) | (0.9239) | |

| Age | −0.0040 | 0.0095 | 0.0069 | 0.0121 | 0.0028 | 0.0125 *** | 0.0054 ** |

| (−0.6681) | (1.5957) | (0.6781) | (1.2366) | (0.7726) | (4.5118) | (2.0509) | |

| State | 0.0286 | 0.0469 | 0.0520 | −0.0078 | 0.0398 | ||

| (0.2577) | (0.3823) | (0.9733) | (−0.1683) | (0.9511) | |||

| Board | −0.3491 | 0.0864 | −0.4954 | −0.1565 | −0.1968 | −0.3463 *** | 0.0626 |

| (−1.5087) | (0.3797) | (−1.2346) | (−0.5035) | (−1.4297) | (−3.3751) | (0.7117) | |

| Dttoprc | 0.0150 | 0.0046 | −0.1080 | 0.0535 | −0.0283 *** | −0.0181 ** | −0.0218 |

| (0.4758) | (0.4018) | (−0.8535) | (0.3747) | (−3.6926) | (−2.3887) | (−1.5827) | |

| Cash | 0.0032 * | −0.0067 | −0.1121 *** | 0.0147 | 0.0089 *** | 0.0061 | 0.0002 |

| (1.8145) | (−0.8040) | (−2.8425) | (0.6200) | (2.6446) | (1.1408) | (0.1867) | |

| Constant | 5.2220 *** | 5.3930 *** | −1.1738 | −1.6490 * | −1.5174 *** | −1.3231 *** | −2.2784 *** |

| (6.8933) | (8.9802) | (−0.9307) | (−1.7757) | (−4.7456) | (−5.4003) | (−9.8453) | |

| Sample Size | 977 | 1824 | 63 | 110 | 526 | 1490 | 1449 |

| R-squared | 0.672 | 0.597 | 0.778 | 0.746 | 0.676 | 0.254 | 0.196 |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| F-value | 14.59 | 46.71 | 2.14 | 5.15 | 9.33 | 33.44 | 23.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. The Impact of Philanthropic Donations on Corporate Future Stock Returns Under the Sustainable Development Philosophy—From the Perspective of ESG Rating Constraints. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010005

Chen Y, Wang Y, Liu C. The Impact of Philanthropic Donations on Corporate Future Stock Returns Under the Sustainable Development Philosophy—From the Perspective of ESG Rating Constraints. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yunqiao, Yawen Wang, and Cunjing Liu. 2026. "The Impact of Philanthropic Donations on Corporate Future Stock Returns Under the Sustainable Development Philosophy—From the Perspective of ESG Rating Constraints" International Journal of Financial Studies 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010005

APA StyleChen, Y., Wang, Y., & Liu, C. (2026). The Impact of Philanthropic Donations on Corporate Future Stock Returns Under the Sustainable Development Philosophy—From the Perspective of ESG Rating Constraints. International Journal of Financial Studies, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010005