A Momentum-Based Normalization Framework for Generating Profitable Analyst Sentiment Signals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Analyst Recommendation Literature

- 1 = Strong Buy (most bullish recommendation).

- 2 = Buy.

- 3 = Hold (neutral stance).

- 4 = Sell.

- 5 = Strong Sell (most bearish recommendation).

2.2. Momentum and Information Diffusion

2.3. Information Content and Market Efficiency

2.4. Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing Advances

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Sample Construction

- Sufficient Analyst Coverage: Large-cap stocks attract multiple analyst firms (mean coverage: 28 firms per stock after name standardization), providing rich data for within-firm normalization.

- Sector Diversification: Equal representation across sectors (Information Technology, Financials, Healthcare, Consumer Discretionary, etc.) prevents sector-specific biases.

- Market Representativeness: These 106 stocks represent the top market concentration holdings across each sector.

- Data Quality: Liquid stocks with continuous trading minimize microstructure noise.

- Analyst Grades Dataset: 68,660 individual rating events from 270 distinct brokerage firms.

- Consensus Recommendations: 7844 monthly aggregate recommendation distributions.

- Price Data: 17,308 monthly dividend-adjusted observations.

3.2. Rating Taxonomy and Standardization

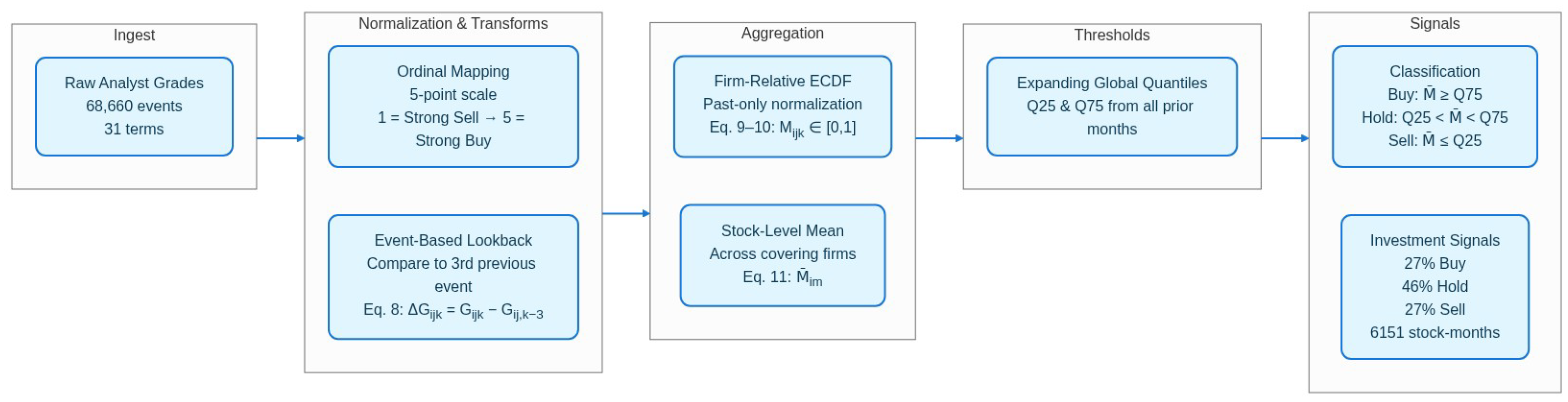

3.3. The Momentum Normalization Framework

3.3.1. Mathematical Formulation

- = count of historical grade changes by firm j that are strictly less than the current change.

- = half-weight for historical changes equal to the current change (standard ECDF convention for ties).

- The sum gives the rank position of the current change.

- = total count of all historical grade changes by firm j before month m.

- by construction (percentile rank).

- Only uses past data: ensures no look-ahead bias.

- Firm-specific: normalizes within each brokerage’s historical distribution.

- Cross-stock: includes firm j’s ratings on ALL stocks, not just stock i.

- = the investment signal for stock i in month m.

- = a stock i’s average momentum score in month m (from Step 3).

- = the 25th percentile calculated using all stocks’ momentum scores from months prior to m (expanding window).

- = the 75th percentile calculated using all stocks’ momentum scores from months prior to m (expanding window).

- Stock 1 (AAPL): 0.480;

- Stock 2 (MSFT): 0.720;

- Stock 3 (GOOGL): 0.250;

- … (103 more stocks).

- = 0.35;

- = 0.65.

- MSFT (0.720 ≥ 0.65) → Buy;

- AAPL (0.35 < 0.480 < 0.65) → Hold;

- GOOGL (0.250 ≤ 0.35) → Sell.

3.3.2. Comprehensive Illustrative Example: Goldman Sachs Rating Apple (AAPL)

3.4. Benchmark Models

3.4.1. Plurality Vote Method

3.4.2. Buy-Ratio Threshold Method

- Buy: BuyRatio ≥ 0.6.

- Hold: 0.4 < BuyRatio < 0.6.

- Sell: BuyRatio ≤ 0.4.

3.5. Data Coverage and Temporal Patterns

- Consensus-based models: 7633 symbol–month observations.

- Grade-based models (including momentum): 6151 symbol–month observations.

- Coverage gap: 1482 symbol–months (19.4%) have consensus data but no rating events.

- Provides monthly snapshots of aggregate analyst sentiment.

- Includes carried-forward ratings when no changes occur.

- Updates monthly regardless of analyst activity.

- Example: If 10 analysts cover AAPL and none change ratings in February, consensus still reports “10 Buy, 0 Hold, 0 Sell”.

- Requires actual analyst rating events (upgrades/downgrades).

- No observation if no analyst changes ratings.

- Captures periods of active information processing.

- Example: If no analyst changes AAPL ratings in February, no grade-based observation exists.

- Mean time since last analyst grade: 2.8 months.

- Distribution highly skewed: 66% have exactly a 1-month gap.

- Concentration in traditionally quiet periods (August, December).

- Lower volatility during missing months (mean realized volatility: 18.2% vs. 23.1% for covered months).

4. Performance Evaluation Framework

4.1. Return Calculation Methodology

4.2. Portfolio Construction and Statistical Testing

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Main Results: Portfolio Performance Comparison

- Economic Significance: The momentum framework generates economically meaningful return spreads that increase with investment horizon (0.96% → 1.36% → 1.94%), consistent with theoretical expectations of gradual information diffusion and price discovery processes.

- Statistical Significance: The momentum approach achieves robust statistical significance across all temporal horizons, with p-values consistently below conventional significance levels (p < 0.003 for all horizons).

- Logical Monotonicity: The momentum framework exhibits intuitive return ordering (Sell < Hold < Buy), while the Plurality Vote method displays paradoxical patterns, with Sell signals generating the highest returns, likely due to the extremely small sample size (57 observations) in the Sell category.

Statistical Significance and Robustness Analysis

- Null Hypothesis (): The true Buy–Sell spread equals zero (momentum signals have no predictive power).

- Alternative Hypothesis (): The true Buy–Sell spread differs from zero.

- Test Statistic: t = 3.66 indicates our observed spread (1.94%) is nearly four standard errors away from zero.

- p-value Interpretation: p < 0.001 means that if the null hypothesis were true (no predictive power), we would observe a spread this large or larger in fewer than 0.1% of random samples.

- 1-month horizon: Spread = 0.96%, t = 3.07, p = 0.002.

- 2-month horizon: Spread = 1.36%, t = 3.07, p = 0.002.

- 3-month horizon: Spread = 1.94%, t = 3.66, p < 0.001.

5.3. Signal Distribution Analysis

| Model | Buy | Hold | Sell | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plurality Vote | 5931 (77.7%) | 1645 (21.6%) | 57 (0.7%) | 7633 |

| Buy-Ratio Classification | 4145 (54.3%) | 1958 (25.7%) | 1530 (20.0%) | 7633 |

| Momentum-Based | 1635 (26.6%) | 2860 (46.5%) | 1656 (26.9%) | 6151 |

5.4. Robustness Analysis

5.4.1. Lookback Period Sensitivity Analysis

5.4.2. Quantile Threshold Research

5.4.3. Taxonomy Sensitivity Analysis

5.5. Sector-Specific Firm Performance Analysis

5.5.1. Methodology: Firm-Isolated Momentum Scoring

- Historical Context Preservation: Each firm’s momentum scores reflect its full behavioral history, avoiding sparse-data problems that could arise from sector-specific normalization.

- Cross-Sector Comparability: Firms covering multiple sectors can be evaluated consistently using a unified scoring methodology.

- Minimum Statistical Thresholds: We require at least five observations in each signal category (Buy/Hold/Sell) per firm–sector combination to ensure robust spread calculations, with a relaxed threshold of three observations for the Gold sector due to lower analyst coverage in precious metals equities.

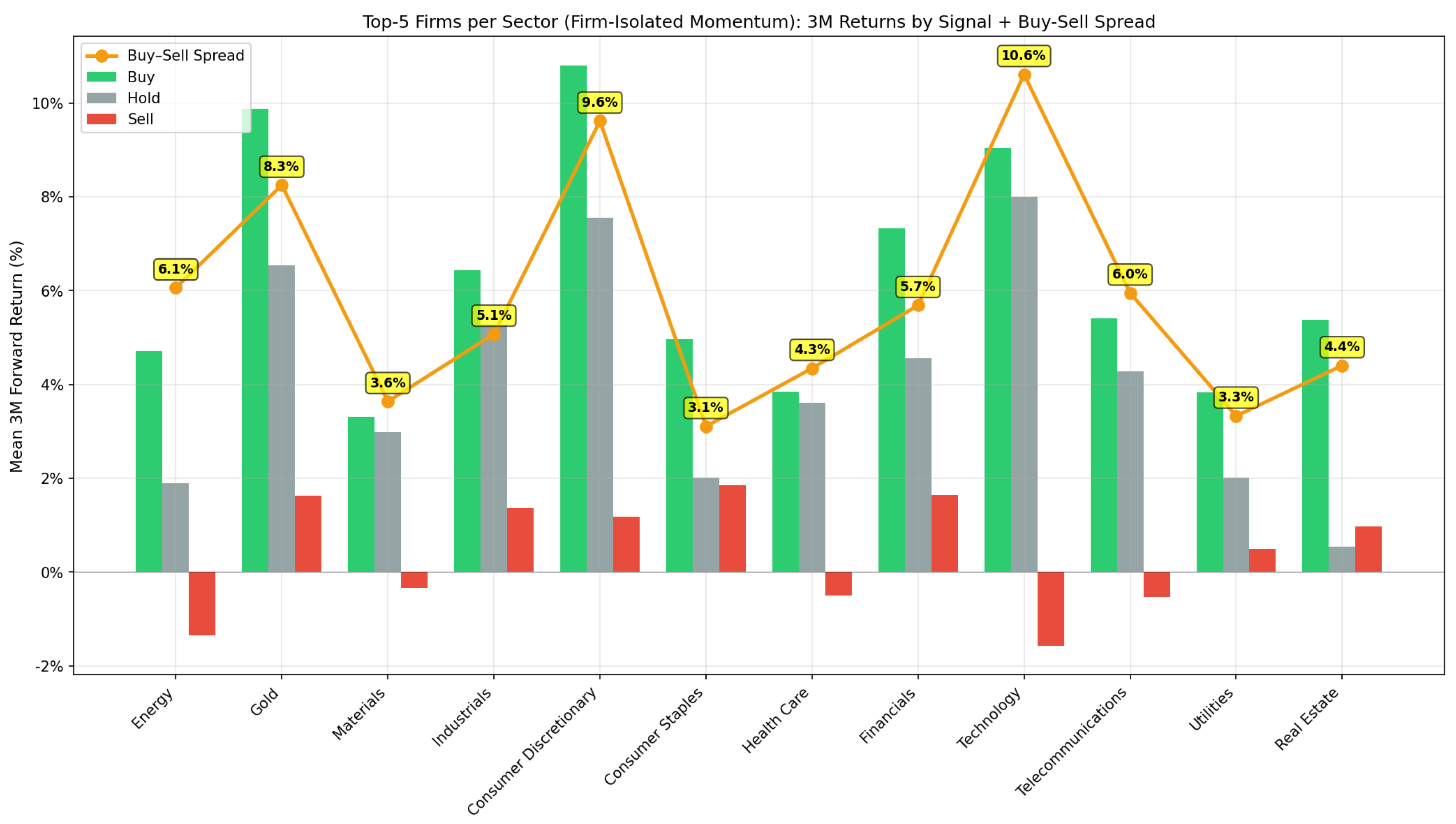

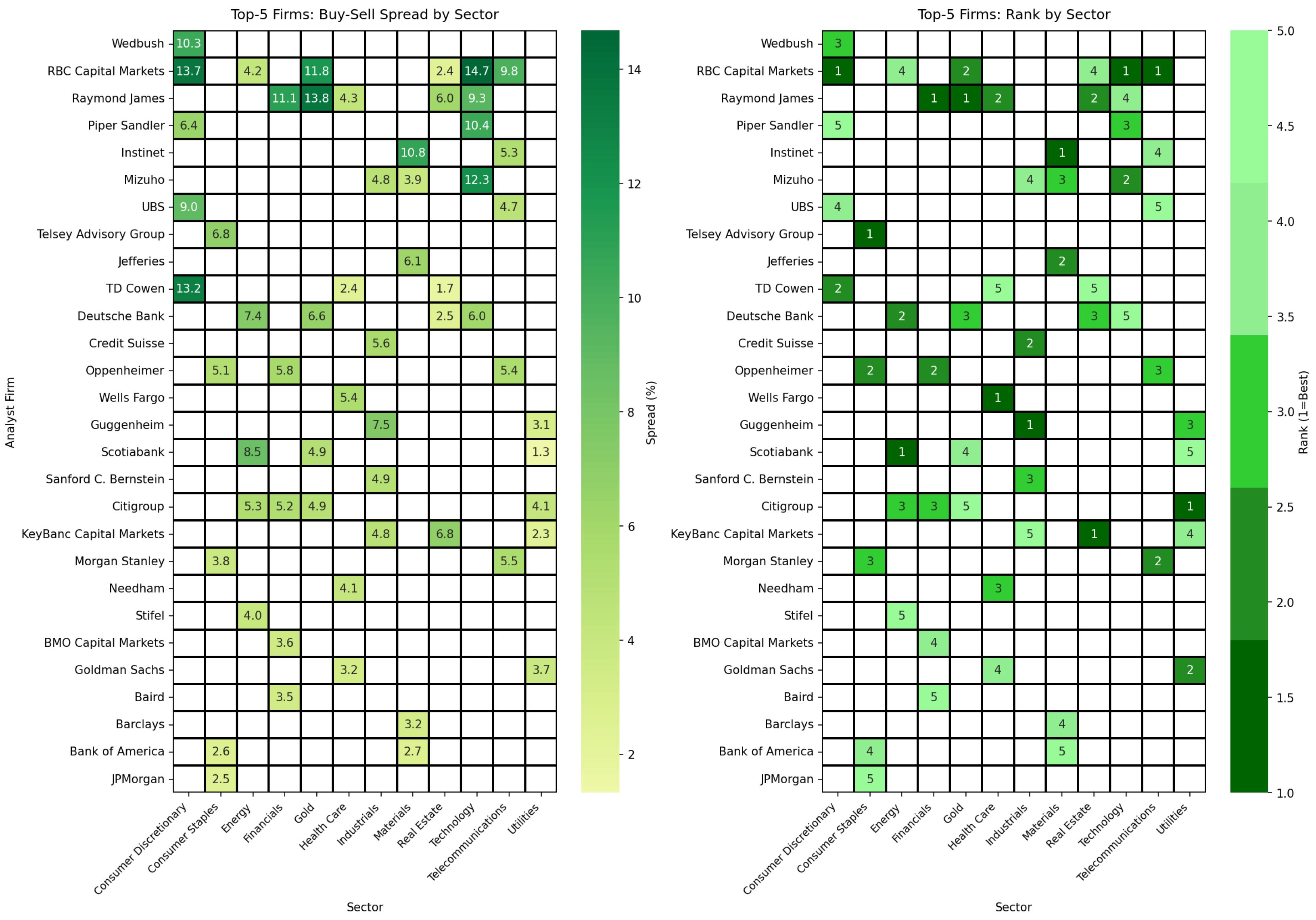

5.5.2. Top-Performing Firms by Sector

5.5.3. Sector Expertise Patterns

5.5.4. Aggregated Top-Five Performance vs. Baseline

5.5.5. Economic and Statistical Interpretation

- Expertise Concentration: By restricting to demonstrated top performers within each sector, the approach effectively filters for analysts with superior information access, processing capabilities, or industry-specific expertise.

- Behavioral Consistency: Firms ranking in the top five exhibit stable performance across time (see Section 5.5.7), suggesting persistent skill rather than transient luck.

- Information Asymmetry Exploitation: The largest improvements occur in sectors with complex business models (Technology: average 10.6%; Gold: 8.4%; Consumer Discretionary: 9.6%), where specialized knowledge provides greater competitive advantage.

5.5.6. Practical Implementation Considerations

- Continuous tracking of firm rankings within each sector.

- Periodic recalibration to adapt to evolving firm performance.

- A minimum of five observations per signal category (Buy/Hold/Sell) for reliable spread calculation per firm–sector pair (a threshold of 3 is used for sectors with lower analyst coverage, such as Gold).

- Large-cap equities with multiple analyst coverage.

- Institutional portfolios with access to comprehensive analyst data.

- Long-only strategies or long–short implementations.

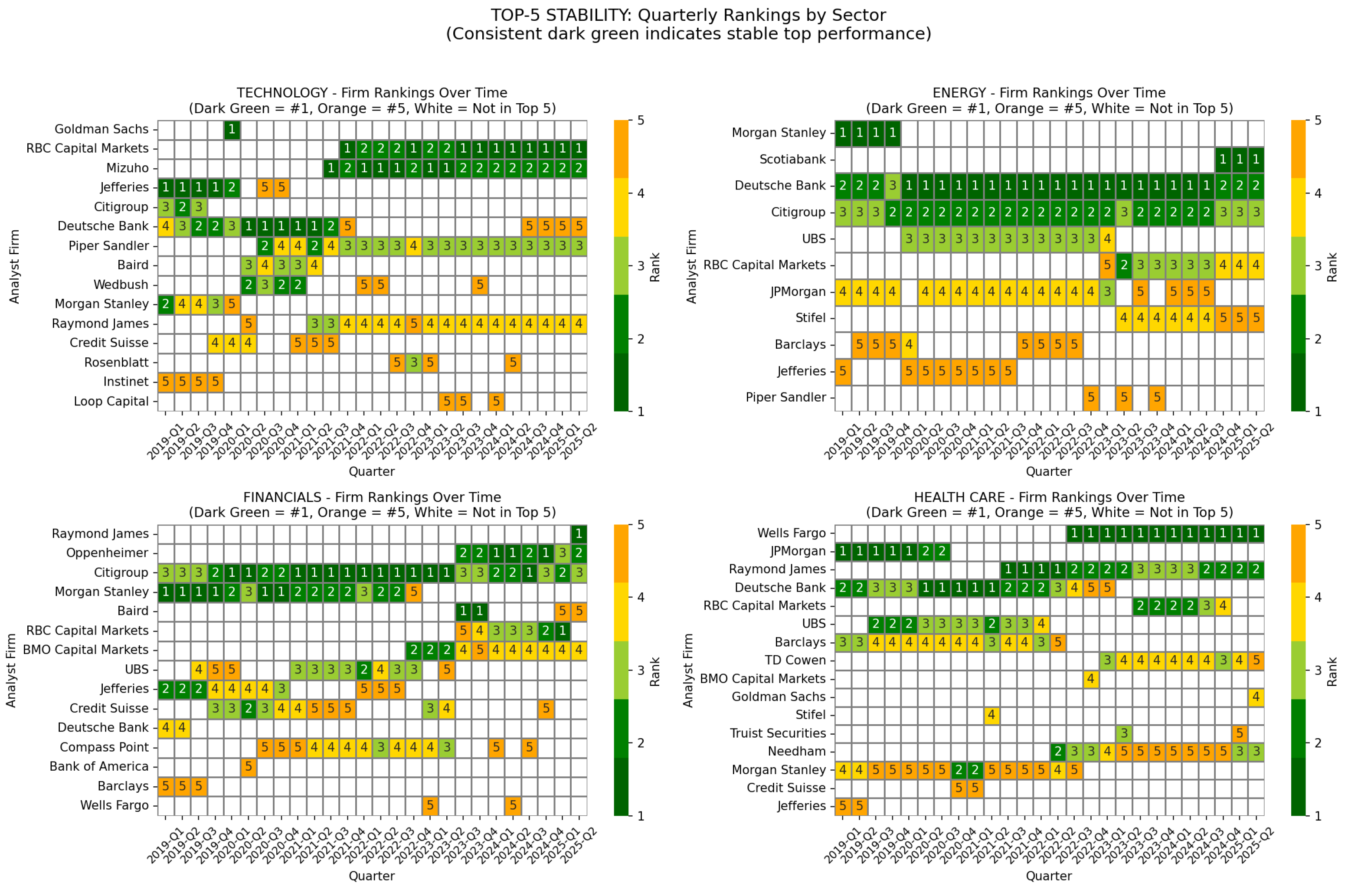

5.5.7. Temporal Stability Analysis

- Cross-Sector Consistency: Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley demonstrate strong temporal consistency, appearing in all four displayed sectors’ top-five rankings across multiple quarters. Deutsche Bank averages 58.7% presence, while Morgan Stanley averages 38.5% across these sectors, indicating robust analytical capabilities that persist across market conditions, despite not always achieving the highest spreads.

- Sector-Specific Variation: Energy and Financials exhibit higher ranking stability (top firms at 100% presence) compared to Technology (top firm at 76.9%), suggesting different dynamics in information advantage persistence across sectors.

- Left panel: Buy–Sell spread magnitudes across all firm–sector combinations, using the red-yellow-green gradient.

- Right panel: Within-sector rankings (1 = best to 5 = fifth), using the green intensity scale.

5.5.8. Implications for the Momentum Framework

6. Discussion and Practical Implementation

6.1. Economic Mechanisms and Literature Comparison

6.2. Out-of-Sample Validation

6.3. Risk-Adjusted Performance

6.3.1. Hold Portfolio Characteristics

- Quality Signal: Stable analyst sentiment often reflects consensus on fundamentally sound companies. When analysts collectively maintain positions without directional changes, this may indicate low uncertainty about firm quality and predictable earnings trajectories.

- Lower Volatility: Hold-classified stocks exhibit the lowest portfolio volatility (7.4% annualized vs. 8.3% for Buy and 9.4% for Sell), contributing to superior Sharpe ratios despite marginally lower returns.

- Defensive Characteristics: The Hold portfolio shows the most defensive market beta (−0.108 vs. −0.079 for Buy), potentially explaining its smaller maximum drawdown (−9.8% vs. −12.2%).

6.3.2. Understanding Long–Short Performance

- Stock Selection vs. Hedged Strategy: The framework excels at identifying stocks likely to outperform within their risk class (generating positive alpha for all signal categories), but the similar risk profiles prevent meaningful long–short alpha extraction.

- Level vs. Spread Information: All portfolios generate positive alpha relative to factor benchmarks, indicating the analyst sentiment signal captures information orthogonal to standard factors. Within our large-cap sample, this information advantage manifests as level (all portfolios elevated above benchmark) rather than spread (differential performance between Buy and Sell), though this pattern may differ in more heterogeneous stock universes.

- Implementation Guidance: Practitioners should employ the framework for long-only stock selection or tactical overweighting rather than market-neutral strategies. The Buy signal’s superior Sharpe ratio (1.28) relative to market benchmarks (0.73) validates this application.

6.4. Equilibrium Considerations and Implementation Context

6.5. Implementation Considerations

Baseline vs. Sector-Specific Methodology Selection

6.6. Limitations and Model Assumptions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECDF | Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function |

| GICS | Global Industry Classification Standard |

| CRSP | Center for Research in Security Prices |

| I/B/E/S | Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System |

Appendix A. Supplementary Results

Appendix A.1. Results Summary Against Significance Thresholds

| Criterion | Our Result | Threshold | Pass? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Sample Statistical Significance | ||||

| In-sample p-value (1M) | 0.0022 | <0.05 | ✓ | 1M spread significant at 0.5% |

| In-sample p-value (2M) | 0.0022 | <0.05 | ✓ | 2M spread significant at 0.5% |

| In-sample p-value (3M) | 0.0003 | <0.05 | ✓ | 3M spread significant at 0.1% |

| Multiple Testing Corrections (Benjamini–Hochberg) | ||||

| BH-adjusted p (1M) | 0.0032 | <0.05 | ✓ | Survives FDR correction |

| BH-adjusted p (2M) | 0.0032 | <0.05 | ✓ | Survives FDR correction |

| BH-adjusted p (3M) | 0.0006 | <0.05 | ✓ | Survives FDR correction |

| BH-adjusted tests | 12/15 | majority | ✓ | 80% survive multiple testing |

| Harvey et al. (2016) t > 3.0 Threshold | ||||

| Main 3M spread t-stat | 3.66 | >3.0 | ✓ | Exceeds Harvey threshold |

| Buy FF6 Alpha t-stat | 3.81 | >3.0 | ✓ | Exceeds Harvey threshold |

| Hold FF6 Alpha t-stat | 4.43 | >3.0 | ✓ | Strongest signal |

| Control Variable Robustness | ||||

| Buy coef. (+B/M + Size) | t = 2.71 | >2.0 | ✓ | Signal robust to controls |

| Buy coef. change | <1% | stable | ✓ | 0.0123 → 0.0126 |

| Risk-Adjusted Performance | ||||

| Buy Sharpe Ratio | 1.28 | >1.0 | ✓ | Solid risk-adjusted return |

| Hold Sharpe Ratio | 1.40 | >1.0 | Excellent risk-adjusted return | |

| Hold Max Drawdown | −9.8% | >−20% | ✓ | Best drawdown among signals |

| Net return (3M L-S) | +1.30% | >0% | ✓ | After transaction costs |

| Out-of-Sample Validation | ||||

| OOS 1M Retention | 107% | >50% | ✓ | OOS (+1.03%) exceeds IS (+0.96%) |

Appendix A.2. Risk-Adjusted Performance Metrics

| Metric | Buy | Hold | Sell | Long–Short |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Return (Monthly) | 1.25% | 1.23% | 1.14% | 0.11% |

| Mean Return (Annual) | 15.0% | 14.7% | 13.7% | 1.3% |

| Std Dev (Monthly) | 2.41% | 2.14% | 2.73% | 1.38% |

| Sharpe Ratio (Ann.) | 1.28 | 1.40 | 0.99 | −0.64 |

| Sortino Ratio | 1.75 | 2.04 | 1.35 | −0.94 |

| Max Drawdown | −12.2% | −9.8% | −15.7% | −12.1% |

| N Observations | 1635 | 2860 | 1656 | 76 months |

Appendix A.3. Market Benchmark Comparison

| Panel A: Benchmark Performance (January 2019–April 2025, 76 months) | ||||

| Benchmark | Mean Monthly | Std Dev | Sharpe Ratio | Cumulative |

| Market (MKT-RF) | 1.09% | 5.18% | 0.73 | 106.5% |

| Price Momentum (MOM) | 0.14% | 4.33% | 0.11 | 3.5% |

| Panel B: Portfolio vs. Market Comparison | ||||

| Portfolio | Sharpe | vs. Market | Improvement | |

| Buy | 1.28 | +0.55 | +75% | |

| Hold | 1.40 | +0.67 | +92% | |

| Sell | 0.99 | +0.26 | +36% | |

| Long–Short | −0.64 | −1.37 | −188% | |

Appendix A.4. Fama–French Factor Regressions

| Panel A: Alpha Estimates by Model and Signal | |||||

| Model | Signal | (Monthly) | (Annual) | t-Stat | p-Value |

| FF3 | Buy | 1.18% | 14.2% | 4.10 | 0.0001 |

| FF5 | Buy | 1.16% | 13.9% | 3.93 | 0.0002 |

| FF6 | Buy | 1.13% | 13.6% | 3.81 | 0.0003 |

| FF3 | Hold | 1.18% | 14.2% | 4.67 | <0.0001 |

| FF5 | Hold | 1.17% | 14.0% | 4.53 | <0.0001 |

| FF6 | Hold | 1.16% | 13.9% | 4.43 | <0.0001 |

| FF3 | Sell | 1.07% | 12.8% | 3.28 | 0.0016 |

| FF5 | Sell | 1.05% | 12.6% | 3.15 | 0.0024 |

| FF6 | Sell | 1.04% | 12.5% | 3.09 | 0.0029 |

| FF6 | Long–Short | −0.11% | −1.3% | −0.65 | 0.517 |

| Panel B: FF6 Factor Loadings (Buy Portfolio) | |||||

| Factor | t-Stat | Interpretation | |||

| Mkt-RF | −0.08 | −1.23 | Slight defensive tilt | ||

| SMB | 0.21 | 1.70 | Small positive size exposure | ||

| HML | −0.06 | −0.63 | Minimal value exposure | ||

| RMW | 0.12 | 0.83 | Slight quality tilt | ||

| CMA | −0.003 | −0.02 | Minimal investment factor exposure | ||

| MOM | 0.06 | 0.67 | Minimal momentum factor exposure | ||

Appendix A.5. Out-of-Sample Validation Details

| Signal Month | Horizon | N Buy | N Sell | Buy Ret | Sell Ret | Spread |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2025 | 1M | 16 | 24 | +3.96% | +3.37% | +0.59% |

| June 2025 | 1M | 20 | 19 | −0.73% | −2.24% | +1.51% |

| July 2025 | 1M | 27 | 44 | +4.01% | +4.92% | −0.91% |

| August 2025 | 1M | 19 | 12 | +2.79% | +0.28% | +2.51% |

| September 2025 | 1M | 24 | 18 | +1.46% | +0.01% | +1.45% |

| OOS Average | 1M | – | – | – | – | +1.03% |

| In-Sample | 1M | – | – | – | – | +0.96% |

| Retention Rate | – | – | – | – | – | 107% |

Appendix A.6. Multiple Testing Corrections

| Test | t-Stat | Raw p | BH Threshold | BH-Adj. p | Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Spread Results | |||||

| 3M Buy–Sell Spread | 3.66 | 0.0003 | 0.020 | 0.0006 | Yes *** |

| 1M Buy–Sell Spread | 3.07 | 0.0022 | 0.030 | 0.0032 | Yes *** |

| 2M Buy–Sell Spread | 3.07 | 0.0022 | 0.033 | 0.0032 | Yes *** |

| Factor-Adjusted Alphas (FF6) | |||||

| Buy Portfolio | 3.81 | 0.0003 | 0.023 | 0.0006 | Yes *** |

| Hold Portfolio | 4.43 | <0.0001 | 0.010 | 0.0002 | Yes *** |

| Sell Portfolio | 3.09 | 0.0029 | 0.040 | 0.0037 | Yes *** |

| Long–Short | −0.65 | 0.517 | 0.043 | 0.597 | No |

| Academic Thresholds | |||||

| Harvey et al. (2016) t > 3.0 | Main spreads (t = 3.07–3.66) and Buy/Hold alphas (t = 3.81–4.43) exceed threshold | ||||

| Bonferroni (/15) | Threshold = 0.0033; Main 3M spread (p = 0.0003) significant | ||||

Appendix A.7. Transaction Cost Analysis

| Portfolio | Gross 3M Return | Net 3M Return | Cost Impact | Break-Even Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buy | 4.68% | 4.39% | −0.29% | N/A |

| Hold | 3.44% | 3.15% | −0.29% | N/A |

| Sell | 2.74% | 2.45% | −0.29% | N/A |

| Long–Short | 1.94% | 1.30% | −0.64% | ∼130 bps |

Appendix A.8. Control Variable Regressions

| (1) Baseline | (2) + B/M | (3) + B/M + Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef. | t-Stat | Coef. | t-Stat | Coef. | t-Stat |

| Constant | 0.0345 *** | 12.61 | 0.0382 *** | 11.44 | 0.0123 | 0.24 |

| Signal_Buy | 0.0123 *** | 2.64 | 0.0126 *** | 2.69 | 0.0126 *** | 2.71 |

| Signal_Sell | −0.0070 | −1.52 | −0.0067 | −1.44 | −0.0066 | −1.43 |

| B/M Ratio | – | – | −0.0112 * | −1.93 | −0.0102 * | −1.68 |

| Log (Market Cap) | – | – | – | – | 0.0010 | 0.51 |

| Buy–Sell Spread | 1.94% | 1.92% | 1.93% | |||

| N | 6120 | 6120 | 6120 | |||

| R2 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |||

References

- Ali, U., & Hirshleifer, D. (2020). Shared analyst coverage: Unifying momentum spillover effects. Journal of Financial Economics, 136(3), 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, P., Mikhail, M. B., & Au, A. S. (2005). Information content of equity analyst reports. Journal of Financial Economics, 75(2), 245–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. M., Lehavy, R., McNichols, M., & Trueman, B. (2001). Can investors profit from the prophets? Security analyst recommendations and stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 56(2), 531–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brav, A., & Lehavy, R. (2003). An empirical analysis of analysts’ target prices: Short-term informativeness and long-term dynamics. The Journal of Finance, 58(5), 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, J. S., Cornell, B., Landsman, W. R., & Rountree, B. (2006). How do analyst recommendations respond to major news? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(1), 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T. C. (2006). The value of client access to analyst recommendations. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S., Kelly, B., & Xiu, D. (2020). Empirical asset pricing via machine learning. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(5), 2223–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. R., Liu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2016). …and the cross-section of expected returns. Review of Financial Studies, 29(1), 5–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H., Lim, T., & Stein, J. C. (2000). Bad news travels slowly: Size, analyst coverage, and the profitability of momentum strategies. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A. H., Wang, H., & Yang, Y. (2023). FinBERT: A large language model for extracting information from financial text. Contemporary Accounting Research, 40(2), 806–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, N., Kim, J., Krische, S. D., & Lee, C. M. (2004). Analyzing the analysts: When do recommendations add value? The Journal of Finance, 59(3), 1083–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, N., & Kim, W. (2006). Value of analyst recommendations: International evidence. Journal of Financial Markets, 9(3), 274–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (1993). Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. The Journal of Finance, 48(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z. T., Kelly, B., & Xiu, D. (2019). Predicting returns with text data. NBER working paper no. w26186. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3446492 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Liddell, T. M., & Kruschke, J. K. (2018). Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, J., Lockwood, L., Miao, H., Uddin, M. R., & Li, K. (2023). Does analyst optimism fuel stock price momentum? Journal of Behavioral Finance, 24(4), 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, R. K., & Stulz, R. M. (2011). When are analyst recommendation changes influential? The Review of Financial Studies, 24(2), 593–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H., Zhu, R., Wang, C., Yao, Z., & Zaremba, A. (2025). The gap between you and your peers matters: The net peer momentum effect in China. Modern Finance, 3(3), 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lira, A., & Tang, Y. (2023). Can ChatGPT forecast stock price movements? Return predictability and large language models. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4412788 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Malmendier, U., & Shanthikumar, D. (2007). Are small investors naive about incentives? Journal of Financial Economics, 85(2), 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S., & Alaghband, G. (2024). Fin-ALICE: Artificial linguistic intelligence causal econometrics. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(12), 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, R. D., & Pontiff, J. (2016). Does academic research destroy stock return predictability? The Journal of Finance, 71(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, K. L. (1996). Do brokerage analysts’ recommendations have investment value? The Journal of Finance, 51(1), 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ordinal Value | Rating Category | Specific Terms | Economic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Strong Buy | Strong Buy, Top Pick, Conviction Buy | Highest-conviction positive ratings designating a firm’s best investment ideas |

| 4 | Buy | Buy, Overweight, Outperform, Add, Accumulate, Long Term Buy, Market Outperform, Sector Outperform, Positive, Above Average | Standard positive ratings implying expected returns exceeding relevant benchmarks |

| 3 | Hold | Hold, Neutral, Equal Weight, Market Perform, Sector Perform, Peer Perform, In Line, Perform, Mixed, Average, Market Weight, Sector Weight | Neutral ratings implying expected returns consistent with relevant benchmarks |

| 2 | Sell | Sell, Underweight, Underperform, Reduce, Sector Underperform, Market Underperform, Negative | Standard negative ratings implying expected returns below relevant benchmarks |

| 1 | Strong Sell | Strong Sell | Highest-conviction negative ratings |

| Stage | Input Data and Context | Mathematical Operation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Event Lookback | Current Event (k): Goldman rates AAPL “Neutral” (3) Reference Event (): Goldman rated AAPL “Buy” (4) Context: A downgrade relative to the 3rd prior event. | −1 | |

| 2. Firm History | Goldman’s Prior Changes (): Context: How rare is a −1 change for this specific firm? | 3.5 | |

| 3. Normalization | Rank Position: 3.5 Total History (N): 13 Context: Convert rank to percentile score (ECDF). | 0.269 | |

| 4. Aggregation | Active Firms for AAPL (Month m): 1. Goldman Sachs () 2. Morgan Stanley () 3. JPMorgan () | 0.480 | |

| 5. Classification | Stock Score: 0.480 Global Quantiles (Expanding Window): (Sell Threshold) (Buy Threshold) | Logic: | HOLD |

| Dataset | Statistic | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Grades Dataset | Total Grade Events | 68,660 |

| Post-2019 Grade Events | 42,015 | |

| Unique Stocks | 109 | |

| Unique Analyst Firms | 270 | |

| Unique Grade Terms | 31 | |

| Consensus Dataset | Total Observations | 7844 |

| Post-2019 Observations | 7843 | |

| Unique Stocks | 110 | |

| Price Dataset | Total Monthly Prices | 17,308 |

| Unique Stocks | 106 | |

| Aligned Universe | Common Stocks (All Datasets) | 106 |

| Momentum Model Coverage | 6151 |

| Model | Signal | 1M Return | 2M Return | 3M Return | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plurality Vote | |||||

| Buy | 1.2% | 2.5% | 3.7% | 5929 | |

| Hold | 0.8% | 1.7% | 2.5% | 1645 | |

| Sell | 8.5% | 14.9% | 20.2% | 57 | |

| Buy–Sell Spread | −7.3% | −12.4% | −16.5% | ||

| t-statistic | −1.78 | −1.61 | −1.60 | ||

| p-value | 0.081 | 0.112 | 0.115 | ||

| Buy-Ratio | |||||

| Buy | 1.2% | 2.5% | 3.7% | 4145 | |

| Hold | 1.2% | 2.5% | 3.6% | 1956 | |

| Sell | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.1% | 1530 | |

| Buy–Sell Spread | +0.2% | +0.5% | +0.6% | ||

| t-statistic | 0.64 | 1.14 | 1.01 | ||

| p-value | 0.521 | 0.256 | 0.314 | ||

| Momentum-Based | |||||

| Buy | 1.84% | 3.11% | 4.68% | 1635 | |

| Hold | 1.14% | 2.34% | 3.44% | 2860 | |

| Sell | 0.87% | 1.74% | 2.74% | 1656 | |

| Buy–Sell Spread | +0.96% *** | +1.36% *** | +1.94% *** | ||

| t-statistic | 3.07 | 3.07 | 3.66 | ||

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Panel A: Calendar-Based Lookback (compare to rating N months ago, Q20/Q80 thresholds) | ||||||

| Lookback | 1M Spread | t-Stat | 2M Spread | t-Stat | 3M Spread | t-Stat |

| 3M-calendar | +0.41% | 1.31 | +0.58% | 1.29 | +1.48% ** | 2.68 |

| 4M-calendar | +0.63% * | 2.12 | +0.78% | 1.84 | +0.96% | 1.86 |

| 5M-calendar | +0.39% | 1.43 | +0.42% | 1.10 | +0.94% * | 1.99 |

| 6M-calendar | +0.56% * | 2.14 | +0.37% | 1.00 | +0.57% | 1.26 |

| Panel B: Event-Based Lookback (compare to Nth previous rating event, Q25/Q75 thresholds) | ||||||

| Lookback | 1M Spread | t-Stat | 2M Spread | t-Stat | 3M Spread | t-Stat |

| 2-event | +0.89% ** | 2.58 | +0.78% | 1.60 | +1.22% * | 2.07 |

| 3-event (selected) | +0.96% *** | 3.07 | +1.36% *** | 3.07 | +1.94% *** | 3.66 |

| 4-event | +0.67% * | 2.08 | +1.21% ** | 2.67 | +1.52% ** | 2.77 |

| 5-event | +0.82% ** | 2.57 | +1.19% ** | 2.65 | +1.53% ** | 2.84 |

| Panel A: Lookback Type Comparison (best threshold for each method) | |||||

| Lookback Type | Best Threshold | 3M Spread | t-Stat | p-Value | |

| Event-based (3-event) | Q25/Q75 expanding | 1.94% | 3.66 | 0.0003 | |

| Calendar-based (3-month) | Q20/Q80 expanding | 1.48% | 2.68 | 0.0074 | |

| Panel B: Threshold Configurations (Event-Based 3-Event Lookback) | |||||

| Threshold | Method | 3M Spread | t-Stat | p-Value | Significant? |

| Q25/Q75 | Monthly cross-sectional | 0.44% | 0.81 | 0.417 | No |

| Q20/Q80 | Monthly cross-sectional | 0.34% | 0.56 | 0.575 | No |

| Q15/Q85 | Monthly cross-sectional | 0.09% | 0.13 | 0.899 | No |

| Q25/Q75 | Expanding global | 1.94% | 3.66 | 0.0003 | Yes *** |

| Q20/Q80 | Expanding global | 1.70% | 2.76 | 0.006 | Yes ** |

| Q33/Q67 | Expanding global | 1.43% | 3.26 | 0.001 | Yes ** |

| Q25/Q75 | Rolling (12 m window) | 1.82% | 3.27 | 0.001 | Ye s ** |

| Sector | Top 5 Firms (Ranked) | Best Spread | Agg. Spread | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Discretionary | RBC Capital Markets (#1), TD Cowen (#2), Wedbush (#3), UBS (#4), Piper Sandler (#5) | 13.7% | 9.6% | 80% |

| Consumer Staples | Telsey Advisory Group (#1), Oppenheimer (#2), Morgan Stanley (#3), Bank of America (#4), JPMorgan (#5) | 6.8% | 3.1% | 100% |

| Energy | Scotiabank (#1), Deutsche Bank (#2), Citigroup (#3), RBC Capital Markets (#4), Stifel (#5) | 8.5% | 6.1% | 100% |

| Financials | Raymond James (#1), Oppenheimer (#2), Citigroup (#3), BMO Capital Markets (#4), Baird (#5) | 11.1% | 5.7% | 80% |

| Gold | Raymond James (#1), RBC Capital Markets (#2), Deutsche Bank (#3), Scotiabank (#4), Citigroup (#5) | 13.8% | 8.3% | 80% |

| Healthcare | Wells Fargo (#1), Raymond James (#2), Needham (#3), Goldman Sachs (#4), TD Cowen (#5) | 5.4% | 4.3% | 90% |

| Industrials | Guggenheim (#1), Credit Suisse (#2), Sanford C. Bernstein (#3), Mizuho (#4), KeyBanc (#5) | 7.5% | 5.1% | 100% |

| Materials | Instinet (#1), Jefferies (#2), Mizuho (#3), Barclays (#4), Bank of America (#5) | 10.8% | 3.6% | 90% |

| Real Estate | KeyBanc Capital Markets (#1), Raymond James (#2), Deutsche Bank (#3), RBC Capital Markets (#4), TD Cowen (#5) | 6.8% | 4.4% | 100% |

| Technology | RBC Capital Markets (#1), Mizuho (#2), Piper Sandler (#3), Raymond James (#4), Deutsche Bank (#5) | 14.7% | 10.6% | 70% |

| Telecommunications | RBC Capital Markets (#1), Morgan Stanley (#2), Oppenheimer (#3), Instinet (#4), UBS (#5) | 9.8% | 6.0% | 90% |

| Utilities | Citigroup (#1), Goldman Sachs (#2), Guggenheim (#3), KeyBanc (#4), Scotiabank (#5) | 4.1% | 3.3% | 100% |

| Methodology | Mean Spread (Across Sectors) | N (Obs) |

|---|---|---|

| Momentum: Sector-Specific Top-5 Firms | 5.84% | 5816 |

| Momentum: Full Framework | 1.94% | 6151 |

| Majority Vote | −1.37% | 11,741 |

| Buy-Ratio | −0.10% | 11,741 |

| Improvement Analysis (Sector-by-Sector Comparison): | ||

| Comparison | Mean Spread Improvement | |

| Top-5 vs. Majority Vote | +7.21 percentage points | |

| Top-5 vs. Buy-Ratio | +5.94 percentage points | |

| Metric | Buy | Hold | Sell | Long–Short |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly Return | 1.25% | 1.23% | 1.14% | 0.11% |

| Annualized Return | 15.0% | 14.7% | 13.7% | 1.3% |

| Annualized Volatility | 8.3% | 7.4% | 9.4% | 4.8% |

| Sharpe Ratio | 1.28 | 1.40 | 0.99 | −0.64 |

| Sortino Ratio | 1.75 | 2.04 | 1.35 | −0.94 |

| Max Drawdown | −12.2% | −9.8% | −15.7% | −12.1% |

| Factor | Buy () | Sell () | Same Direction? | L/S () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 1.13% *** | 1.04% *** | Both positive | −0.11% |

| Mkt-RF | −0.079 | −0.093 | Both negative | +0.014 |

| SMB | 0.215 | 0.154 | Both positive | +0.079 |

| HML | −0.063 | −0.109 | Both negative | +0.033 |

| RMW | 0.116 | 0.082 | Both positive | +0.049 |

| CMA | −0.003 | −0.002 | Both ≈zero | +0.024 |

| MOM | 0.058 | 0.021 | Both positive | +0.038 |

| Sector | Top-Firm Stability | Coverage | 3M Spread | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 100% | 100% | 6.1% | Sector-specific |

| Consumer Staples | 100% | 100% | 3.1% | Sector-specific |

| Industrials | 92% | 100% | 5.1% | Sector-specific |

| Real Estate | 92% | 100% | 4.4% | Sector-specific |

| Utilities | 92% | 100% | 3.3% | Sector-specific |

| Telecom | 100% | 90% | 6.0% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Materials | 96% | 90% | 3.6% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Health Care | 65% | 90% | 4.3% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Financials | 100% | 80% | 5.7% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Gold | 100% | 80% | 8.3% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Consumer Disc. | 85% | 80% | 9.6% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

| Technology | 77% | 70% | 10.6% | Baseline (incomplete coverage) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

McCarthy, S.; Alaghband, G. A Momentum-Based Normalization Framework for Generating Profitable Analyst Sentiment Signals. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010004

McCarthy S, Alaghband G. A Momentum-Based Normalization Framework for Generating Profitable Analyst Sentiment Signals. International Journal of Financial Studies. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarthy, Shawn, and Gita Alaghband. 2026. "A Momentum-Based Normalization Framework for Generating Profitable Analyst Sentiment Signals" International Journal of Financial Studies 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010004

APA StyleMcCarthy, S., & Alaghband, G. (2026). A Momentum-Based Normalization Framework for Generating Profitable Analyst Sentiment Signals. International Journal of Financial Studies, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijfs14010004