1. Introduction

The relationship between compensation incentive and executive decision is a critical issue, particularly in emerging economies. Rationalizing CEO compensation is the key focus of compensation incentives, thus prompting scholars to similarly focus on the pay gap of executive teams (

Conyon et al., 2001;

Y.-F. Lin et al., 2013;

Kong et al., 2021;

M. Li & Chen, 2024). Defined as the compensation difference between the CEO and other senior executives, the executive pay gap influences internal governance mechanisms and overall organizational performance (

Dai et al., 2017). However, a disagreement remains regarding what the appropriate pay gap is for promoting company growth. China’s SOEs reform provides us with a unique institutional perspective, allowing us to discuss the divergence using the pay contract anomaly arising from the salary reform. Our study aims to explore how executive pay-rank inversion shapes M&A strategies in SOEs, contributing to the broader discourse on compensation and executive decision.

Previous literature offers two divergent perspectives regarding the optimal executive pay gap. Tournament view suggests that pay dispersion in the corporate hierarchy creates an arena for individuals to compete for promotions and rewards (

Yin & Zhang, 2014;

Kong et al., 2021;

Hallila et al., 2024). Appropriate pay levels effectively enhance managerial motivation, thereby contributing to firm value creation (

Eriksson, 1999;

Banker et al., 2016;

Pathan et al., 2023;

Zhong et al., 2023). Thus, maintaining a large pay gap is deemed necessary. However, some scholars argue from an entrenchment viewpoint that the large pay gap between the CEO and other executives reflects the power of the CEO and that powerful CEOs solidify their power and are thus more likely to misappropriate shareholders’ wealth. These gaps in executive pay may reflect agency problems, potentially reducing company value and performance (

Haß et al., 2015;

H. L. Chan et al., 2020;

Tan, 2024). In China’s salary reform, the recent emergence of the phenomenon of “pay-rank inversion” for executives of SOEs provides a unique opportunity for such a divergence in research.

In 2009, China’s Ministry of Finance, in collaboration with six other governmental departments, jointly introduced the “Guiding Opinions on Further Regulating the Remuneration Management of the Heads of Central Enterprises.” This policy is widely recognized as marking the beginning of China’s executive salary cap system. The principal intent of this reform was to address the increasing disparities in executive pay that emerged from earlier market-oriented compensation practices. Specifically, it established an executive remuneration ceiling anchored to the average salary of regular employees within central SOEs. Following its initial implementation, the government has continuously issued complementary policies to reinforce the effectiveness of this executive salary restriction initiative, targeting primarily senior positions such as chairpersons, CEOs, and party secretaries. However, this regulatory framework concurrently permitted market mechanisms to dictate the pay for lower-ranking executives, thereby unintentionally creating a compensation anomaly in certain SOEs where lower-level executives earned more than their senior counterparts—a phenomenon termed “executive pay-rank inversion.” The significance of this phenomenon lies in its departure from prior scholarly discussions, which predominantly concentrated on the motivational effects of positive incentive structures while largely neglecting the economic implications associated with negative incentive scenarios.

This study investigates the impact of executive pay-rank inversion on mergers and acquisitions (M&A) decisions within state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The focus on M&A activities is driven by several considerations. First, M&A activities have increasingly become critical tools for advancing SOE reforms and hold a prominent strategic position in Chinese government policy (

Liang et al., 2024). Second, executives typically play a pivotal role in M&A decisions due to their substantial discretionary authority (

Moeller et al., 2004;

El-Khatib et al., 2015;

J. Chen et al., 2024). Third, M&A processes are inherently complex and long-term in nature, marked by significant information asymmetry between shareholders and management. This characteristic frequently leads to pronounced agency conflicts (

Masulis et al., 2007;

Z. Chen et al., 2017), thus making M&A activities ideal for exploring the consequences of executive pay-rank inversion.

The theoretical relationship between executive pay-rank inversion and M&A decisions is ambiguous. On one side, information asymmetry and agency issues often result in decreased executive motivation and increased risk aversion (

Bertrand & Schoar, 2003). In line with tournament theory and equity theory, a reduction in explicit compensation incentives—particularly under pay-rank inversion conditions—could exacerbate these agency conflicts, undermining managerial motivation and diminishing willingness to undertake risky strategic initiatives such as M&As. On the other side, executives facing inadequate explicit incentives might resort to M&A activities as alternative mechanisms for personal advancement (

Shi et al., 2017;

Mishra, 2020). Additionally, empire-building theory suggests that CEOs may exploit M&A activities to obscure corporate risks and pursue personal benefits (

C.-Y. Chan et al., 2023). Given the critical importance of M&A decisions for SOE strategic development and the lack of consensus regarding the incentive effects of executive pay-rank inversion, this study is motivated to investigate how pay-rank inversion affects M&A decision-making within SOEs. By systematically examining this phenomenon, we aim to fill a significant empirical gap and contribute to the broader academic discourse concerning the design of optimal executive compensation gaps.

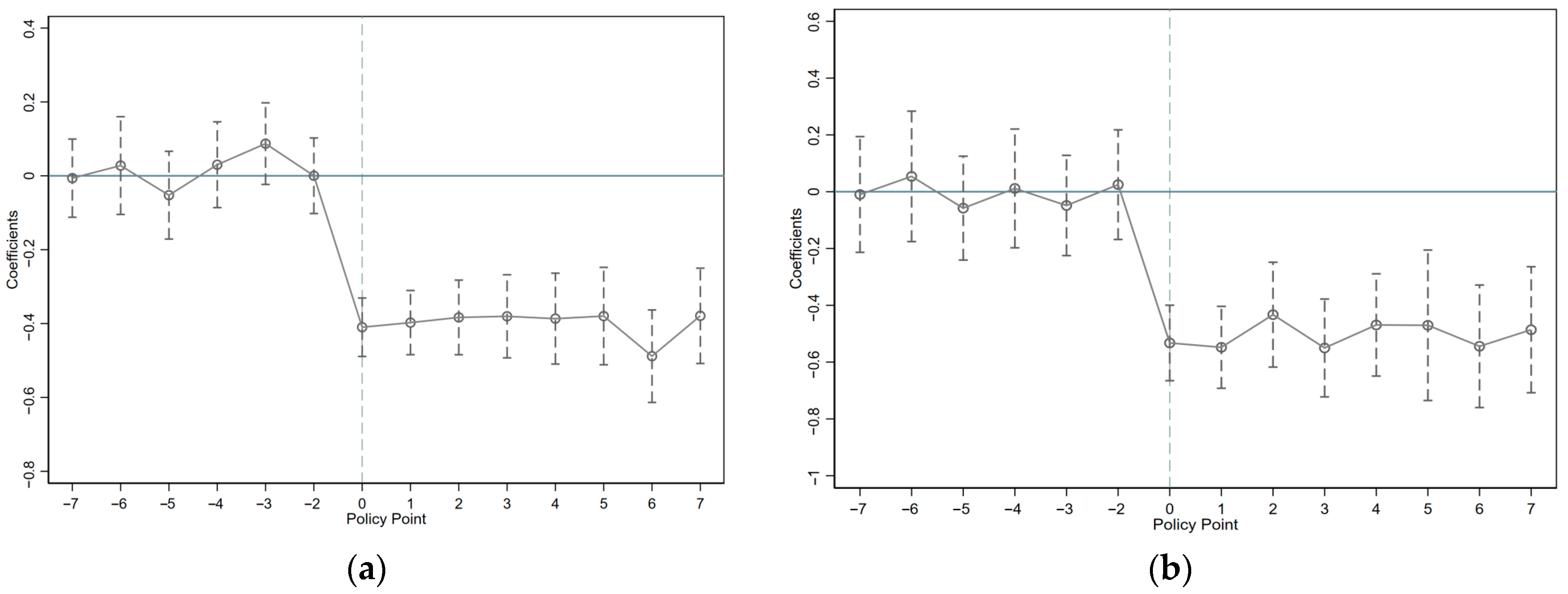

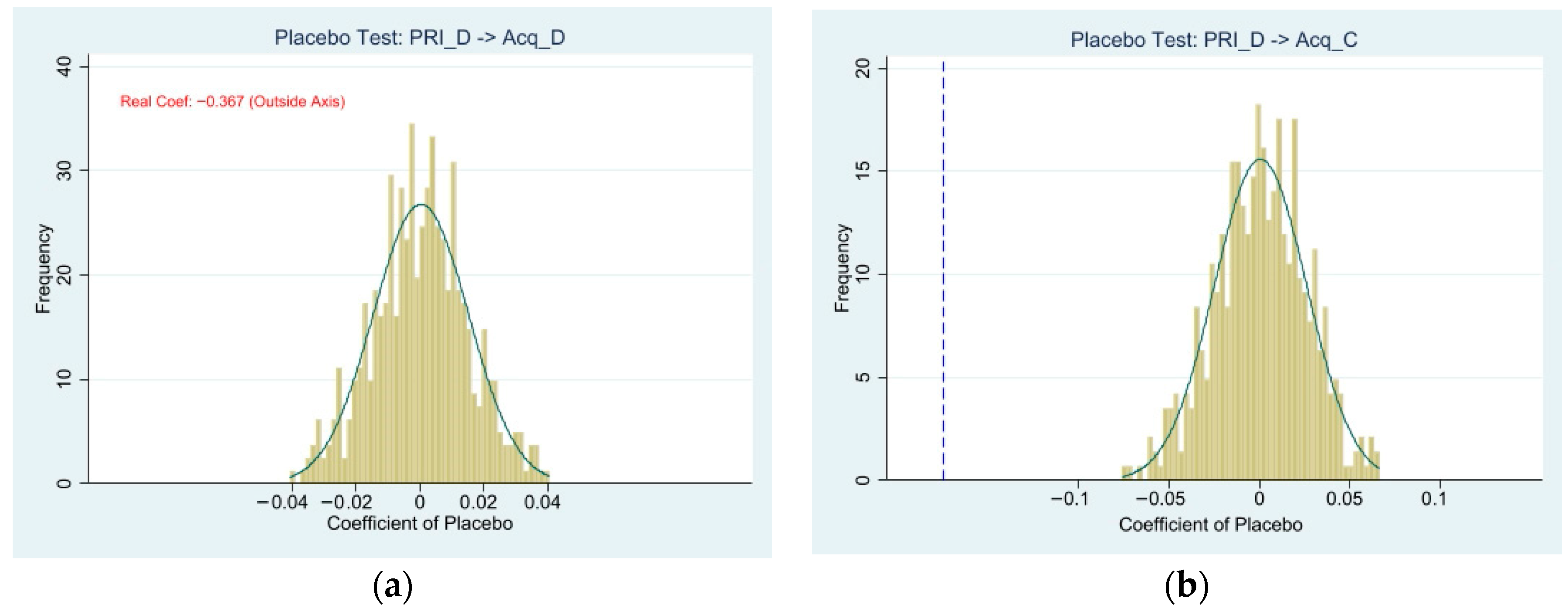

To empirically assess the relationship, we implement a difference-in-differences (DiD) model using data from A-share state-owned listed companies from 2007 to 2022, capturing both the occurrence and degree of pay-rank inversion and using the frequency and occurrence of M&As as measures of corporate acquisition intentions. The final sample consists of 3810 firm-year observations. Our baseline empirical results demonstrate that SOEs experiencing pay-rank inversion (the treatment group) exhibit significantly diminished intentions to engage in M&A activities relative to firms without pay-rank inversion (the control group). These findings are robust to multiple validity checks, with further analyses highlighting that pay-rank inversion primarily depresses M&A intentions by decreasing executive risk tolerance. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis reveals that longer CEO tenures and the presence of equity-based incentives considerably alleviate the negative impact of pay-rank inversion on M&A intentions. From an economic consequences perspective, firms experiencing pay-rank inversion also exhibit comparatively inferior M&A performance outcomes.

The paper contributes to the existing literature in several important respects. First, it extends the current understanding regarding how compensation incentives shape executive decisions. In contrast to earlier studies which predominantly explore optimal executive pay gaps for mitigating agency conflicts (

C. Lin et al., 2011;

Biggerstaff et al., 2019), our research uniquely emphasizes the adverse motivational effects arising from anomalous compensation structures. By investigating the economic consequences of pay-rank inversion, the paper enhances existing frameworks on executive compensation incentives.

Second, this study leverages the distinctive institutional context of China to explore how reforms to SOE executive compensation affect corporate strategic decisions, particularly those involving M&As. While prior literature has addressed the impacts of salary cap policies on corporate performance (

Tong et al., 2024), stock price crash risk (

Bai et al., 2019), managerial perquisites (

Bae et al., 2024), and financial investments (

Tian et al., 2024), the implications of executive pay-rank inversion on M&A strategies remain largely unexplored. Notably,

Tian et al. (

2024) document a positive impact of CEO pay-rank inversion on short-term financial investments. Given that M&As inherently entail higher risks, longer time horizons, and pronounced agency challenges compared to financial investments, they provide an ideal environment for comprehensively examining the broader consequences of pay-rank inversion. Furthermore, the clear observability and measurable long-term impact of M&A events (

Z. Li & Peng, 2021) make them particularly effective for evaluating institutional reforms in executive compensation.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Our paper uses the pay-rank inversion in SOEs as a natural experiment to examine how the anomaly compensation contract shapes firm’s M&A decisions. We find evidence that firms experiencing pay-rank inversion exhibit significantly lower M&A intentions. Pay-rank inversion severely curbs executives’ risk-taking, causing them to avoid high-risk, uncertain-return decisions, which in turn affects their M&A intentions. Moreover, CEO tenure and equity incentives can mitigate the negative impact of pay-rank inversion on M&A enthusiasm. Finally, the study reveals that pay-rank inversion hinders value realization during the M&A process.

Overall, our research uncovers the unforeseen effects of SOE compensation reforms, demonstrating the importance of a reasonable pay gap in the M&A decision-making process of state-owned enterprises. Theoretically, our study contributes to the literature on the executive pay gap and M&A by highlighting how pay-rank inversion shapes M&A decisions within state-owned enterprises. Previous studies have shown divergent views on how to establish a reasonable pay gap. Our study provides evidence on this issue from the perspective of negative compensation incentives. By demonstrating how pay-rank inversion affects M&A intentions and fosters poorer performance in M&As, our findings reveal the unforeseen effects of the Salary Restriction Order. This contribution is particularly relevant for emerging markets, where frequent reform practices do not always benefit the development of domestic state-owned enterprises.

Additionally, the study has clear implications. Firstly, SOEs could consider designing a fair salary gradient based on functions and qualifications to enhance motivation and risk-taking and reduce agency costs. Second, SOEs could reduce government interference in senior management appointments by ensuring stable tenures to facilitate long-term career planning. SOEs could introduce equity incentives to focus executives on long-term development, mitigate moral hazards from pay-rank inversion, increase risk-taking, and enhance M&A enthusiasm, thereby boosting SOE development and achieving high-quality growth of state-owned capital. Third, SOE salary reform should take potential negative effects into account. A rational compensation system is crucial for motivating executives and employees, enhancing work enthusiasm and self-monitoring, driving the enterprise towards high-quality development.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite offering robust empirical evidence, this study has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research.

First, regarding the measurement of our core explanatory variable, pay-rank inversion, this study adopts a specific perspective by focusing solely on the inversion between the top two tiers of SOE management (CEO and other high-level executives). However, some literature explores the phenomenon of pay inversion between the listed SOE and its controlling central enterprise (Group Company). Future studies should extend the scope to investigate the relationship between Group Company-level pay inversion and the listed firm’s M&A activities, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the incentive structure across the entire SOE hierarchy.

Second, in our heterogeneity analysis, we primarily focused on CEO characteristic variables, such as tenure and equity incentive level. Future research could incorporate a wider range of firm-level characteristics, such as corporate governance variables (e.g., board independence, internal control quality), to further explore how these factors modulate the relationship between pay-rank inversion and M&A decisions.

Finally, while this paper empirically verifies the mechanism via diminished risk-taking, pay-rank inversion may affect M&A decisions through other pathways, such as reduced CEO work motivation or engagement. Future work should integrate these alternative mechanisms to provide a deeper and more holistic understanding of the internal logic driving high-level executive decision-making under the condition of pay-rank distortion.