1. Introduction

The traditional option pricing framework, as outlined in the seminal paper by

Black and Scholes (

1973), assumes a frictionless and liquid financial market. However, this framework does not hold when dealing with large-notional derivatives on illiquid assets that are subject to market impact. Empirical microstructure studies show that when large trades or block hedges are executed, liquidity is often depleted, producing immediate price adjustments (

Hasbrouck, 1991). A portion of this impact can persist, as documented in empirical analyses showing that large institutional metaorders leave lasting effects on prices (

Bouchaud et al., 2010;

Tóth et al., 2011). Consequently, the spot price of the underlying—and therefore any derivative hedge—may shift as a direct result of the hedging trades themselves.

A first approach to account for such frictions, most notably the Leland model (

Leland, 1985), incorporates transaction costs by inflating volatility. However, this method captures only the temporary cost of adjusting the hedge and ignores liquidity pressure or any feedback of the hedge on the underlying price. To incorporate such feedback effects, two principal approaches have emerged. The first is a full-hedging approach, introduced by

Liu and Yong (

2005) and further developed in

Loeper (

2018),

Said (

2020),

Bordag and Frey (

2008), and

Abergel and Loeper (

2017), which seeks to eliminate risk entirely but can become impractical because continuously adjusting the hedge can generate prohibitively high option prices, particularly near maturity or when the spot is close to the strike. The second is a partial-hedging approach, exemplified by

Jonsson and Sircar (

2002) and extended in utility- or gain-maximization frameworks such as

Guéant and Pu (

2017), which trade off hedging costs against residual risk but can inadvertently create incentives for the trader to profit from their own impact.

These types of model-driven price manipulation have been highlighted in several theoretical studies, which show that objective-function–based hedging frameworks can inadvertently create incentives for traders to influence prices through their own trades (

Horst & Naujokat, 2011;

Kraft & Kühn, 2011;

Roch, 2022). Such algorithmic or model-induced distortions fall under the broader category of new market manipulation described by

Lin (

2017), where price effects arise not from deliberate intent but as unintended consequences of the trading rules themselves. Empirical research also shows that derivatives markets can exhibit settlement-related distortions or manipulation incentives (

Griffin & Shams, 2018;

R. Jarrow et al., 2018;

Ni et al., 2005). Beyond these derivatives-specific patterns, microstructure research establishes that order flow contains both informational and liquidity-driven components (

Barclay & Warner, 1993;

Easley & O’Hara, 1996;

Huang & Stoll, 1997), and manipulation risks are more acute in settings where price impact includes a permanent component. Empirical studies show that such permanent components arise in institutional trading (

Almgren et al., 2005;

Bouchaud et al., 2010;

Tóth et al., 2011), making lasting price distortions more exploitable than purely temporary execution costs. Together, these observations reveal a conceptual gap: existing models lack a way to capture informational drivers of market impact while ensuring non-manipulable pricing.

To address this gap, we introduce an insider observer: an agent who shares the large trader’s informational advantage but exerts no influence on prices. As

R. A. Jarrow (

1994) explains, in the presence of derivatives the market effectively consists of two venues—the underlying and the derivative—and misalignment between them can create opportunities for manipulation. By analyzing the market from the insider’s perspective, we capture how informational asymmetry modifies the martingale pricing structure and thereby alters the hedging dynamics faced by the large trader. This interpretation—where the large trader’s trading rate reflects informed order flow in an analogous sense to classical microstructure models—motivates a conceptual distinction between informational and mechanical components of permanent impact. Unlike empirical decompositions of order flow into informed and liquidity-driven parts (

Barclay & Warner, 1993;

Easley & O’Hara, 1996;

Huang & Stoll, 1997), our separation is implemented through an insider filtration combined, which isolates only the informed part of permanent impact in the reference measure. This formulation aligns with literature on asymmetric information and filtration enlargement (

Amendinger et al., 1998;

Eyraud-Loisel, 2013;

Grorud & Pontier, 1998;

Hillairet, 2004), although—unlike some of these studies—we do not study the perspective of the uninformed trader.

A key part of our methodology relies on specifying a market-impact structure. The microstructure literature distinguishes between temporary and permanent price impact, and more elaborate formulations also include transient, decaying impact (

Almgren & Chriss, 2001;

Gatheral, 2010). Temporary impact reflects the instantaneous liquidity cost of a trade, whereas permanent impact captures the informational or mechanical footprint left on the mid-price, and both components are well documented empirically (

Hasbrouck, 1991;

Madhavan et al., 1997). In our framework, temporary impact is modelled entirely through a nonlinear transaction-cost function à la Almgren–Chriss, capturing only the mechanical execution cost of adjusting the hedge. Permanent impact is represented by a drift shift in the underlying price process and is decomposed through a Poisson mechanism: the trader knows the expected magnitude of the permanent price displacement (informational component), whereas the random jump arrival times reflect liquidity-driven uncertainty (mechanical component). The insider observer filters out the informational part and treats the mechanical component as exogenous noise, allowing only the latter to enter price formation under the reference measure. In contrast, we do not incorporate transient or decaying impact (

Gatheral, 2012;

Klock, 2014), as our objective is not to model order-book resilience but to isolate informational asymmetry from liquidity-driven price pressure within a tractable continuous-time setting.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 discusses the regulatory notes, challenges and example of unintended market manipulation within derivatives pricing and hedging. It provides a case example and introduces our problem reduction approach by hypothesizing a market with one large trader and an insider trader.

Section 3 describes the stock dynamics and the market impact model used in this paper. Based on this dynamics,

Section 4 explores the pricing equation for the insider trader and elaborates on information-neutral probabilities for asset valuation as a martingale.

Section 5 analyzes the portfolio dynamics of the large trader and formulates the mathematics of its hedging portfolio.

Section 5.2 explores the optimal hedging strategy for the large trader, addressing market manipulation within the stochastic control framework.

Section 6 presents a numerical implementation based on finite-difference methods, comparing the strategies of the large trader, the insider trader, and the classical Black–Scholes hedge. The model’s limitations, potential areas for future research, and the concluding remarks are then discussed in

Section 7 and

Section 8.

2. Challenges in Traditional Hedging Models and Motivation for Our Approach

Empirical microstructure studies show that large order flow generates measurable price pressure even in the absence of news (

Hasbrouck, 1991;

Madhavan et al., 1997). Consequently, large hedging trades in derivative markets can influence the underlying asset price, creating distortions that may appear as spurious price movements or unintended changes in the payoff structure. Understanding and mitigating such effects is essential for traders managing sizeable derivative positions in markets with limited liquidity. This section therefore outlines the forms of market manipulation that are most relevant to large traders, highlights the challenges faced by pricing models that may unintentionally induce these distortions, and introduces our methodological approach for addressing these concerns.

2.1. Regulatory Notes

There are two types of market manipulative strategies, relevant for our ecosystem that is discussed in the regulations.

Abusive Squeeze: An abusive squeeze occurs when a trader deliberately creates a market condition that amplifies their ability to profit from the subsequent price movements of an asset. This typically involves sequentially buying or selling a large quantity of the asset to influence its price in a manner that benefits their trading position. Such actions can lead to artificial price levels. In the context of derivatives, an abusive squeeze might involve a large trader influencing the underlying asset’s price of a derivative contract tied to it. Regulatory bodies recognize this behavior as a form of market abuse (

Financial Conduct Authority, 2005). Related distortions have also been characterized within the market microstructure literature, where conditions for profitable manipulation are formally derived (

Huberman & Stanzl, 2004;

R. A. Jarrow, 1992).

Payoff Manipulation: Payoff manipulation refers to scenarios in which a trader’s actions directly affect the payoff of a derivative instrument through their market impact. By strategically buying or selling the underlying asset, a trader can influence the settlement price of options or other derivatives to their advantage, particularly when holding sufficiently large positions. Such practices are prohibited under regulations designed to safeguard market integrity (

European Parliament and of the Council, 2014;

Financial Conduct Authority, 2005). Theoretical price-impact models likewise show that hedging flows or liquidity shocks can distort settlement levels and derivative payoffs (

Kraft & Kühn, 2011;

Roch, 2022).

One important consideration is that payoff manipulation can also arise unintentionally, for example when delta hedging is performed under models such as Black–Scholes that do not account for the price effects of the hedge itself. Empirical evidence of strike pinning and expiration-day distortions (

Ni et al., 2005) illustrates how such unintended effects can arise in practice.

2.2. Practical Example of Unintended Manipulative Strategies

As a result, the standard delta-hedging strategies derived from these models can inadvertently lead to market conditions that result in payoff manipulation. To further explain this, the following example illustrates how such unintentional manipulation can happen in the case of a KO (Knock-out) call option.

Example 1 (Payoff Manipulation for an Out-of-the-Money Knock-out Call Option).

Consider a large trader who holds a large position of a short-term, out-of-the-money Knock-out (KO) call option with a knock-out barrier set at 105, while the current stock price is 100. A KO call option is a type of barrier option that ceases to exist if the underlying asset’s price reaches or exceeds a specified level, known as the knock-out barrier. If an investor holds a KO call option with a barrier at 105 and the stock price hits 105, the option becomes void and worthless. This characteristic makes KO options particularly sensitive to price movements of the underlying asset near the barrier level, exposing them to potential manipulation more than other types of derivatives.

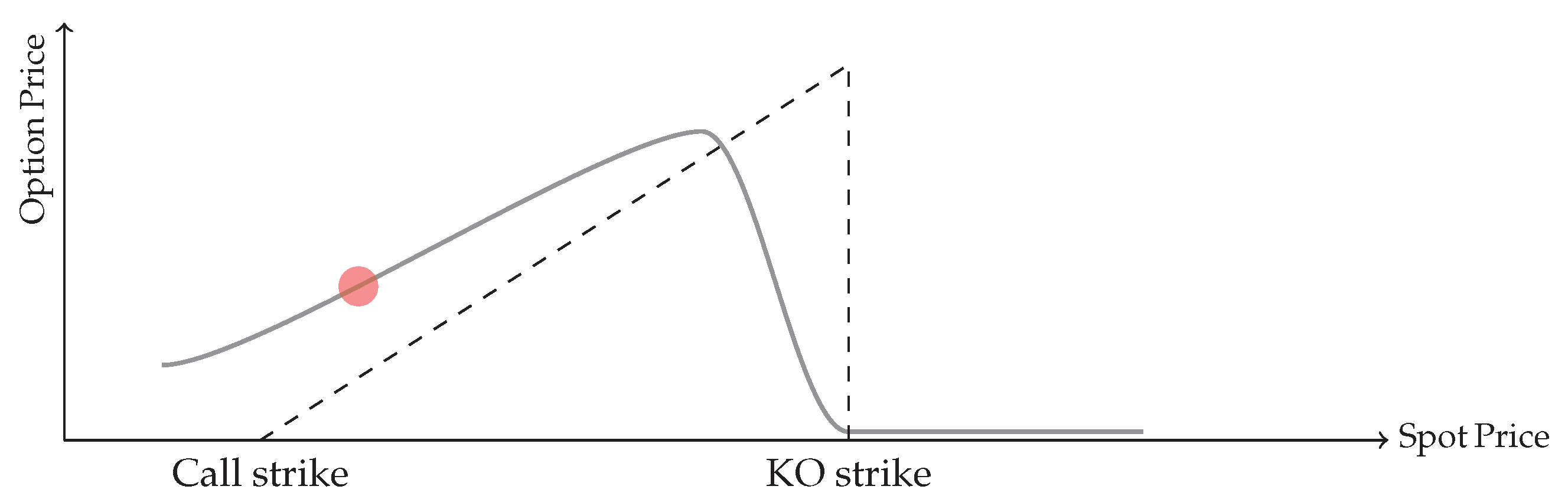

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the spot price of the underlying asset and the price of the Knock-out (KO) call option. In the figure, the horizontal axis represents the spot price of the underlying asset, while the vertical axis denotes the price of the option. The solid line shows how the price of the KO call option changes as the spot price varies. As the spot price increases but remains below the KO barrier, the option price increases, reflecting its growing value. However, as the spot price approaches the KO barrier, the potential for the option to become worthless at the barrier exerts downward pressure on its price. The dashed line represents the payoff of the option at expiry. This payoff is contingent on the spot price relative to the KO barrier. If the spot price remains below the KO barrier at expiry, the option payoff reflects its intrinsic value. Conversely, if the spot price reaches or exceeds the KO barrier, the option is knocked out, resulting in no payoff. In this figure, the current spot price, depicted via a red dot, is in the money (greater than the strike price) but still far from the KO barrier. Under a delta hedging strategy using the classical Black-Scholes model, the seller of the option must purchase more of the underlying asset to hedge their position as the option’s sensitivity to the spot price, i.e., the delta, increases. As delta increases, it reflects the growing sensitivity of the option’s price to changes in the spot price. To maintain a delta-neutral position and mitigate risk, the trader buys additional stock. This strategy offsets the option’s price changes with corresponding movements in the underlying asset.

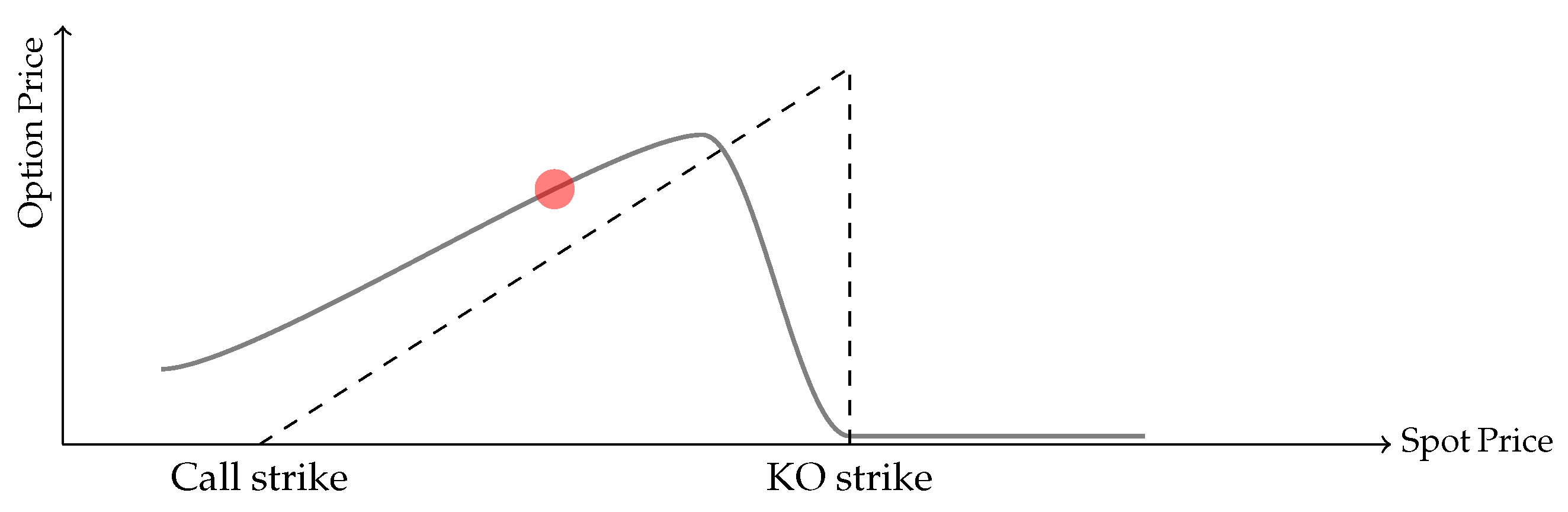

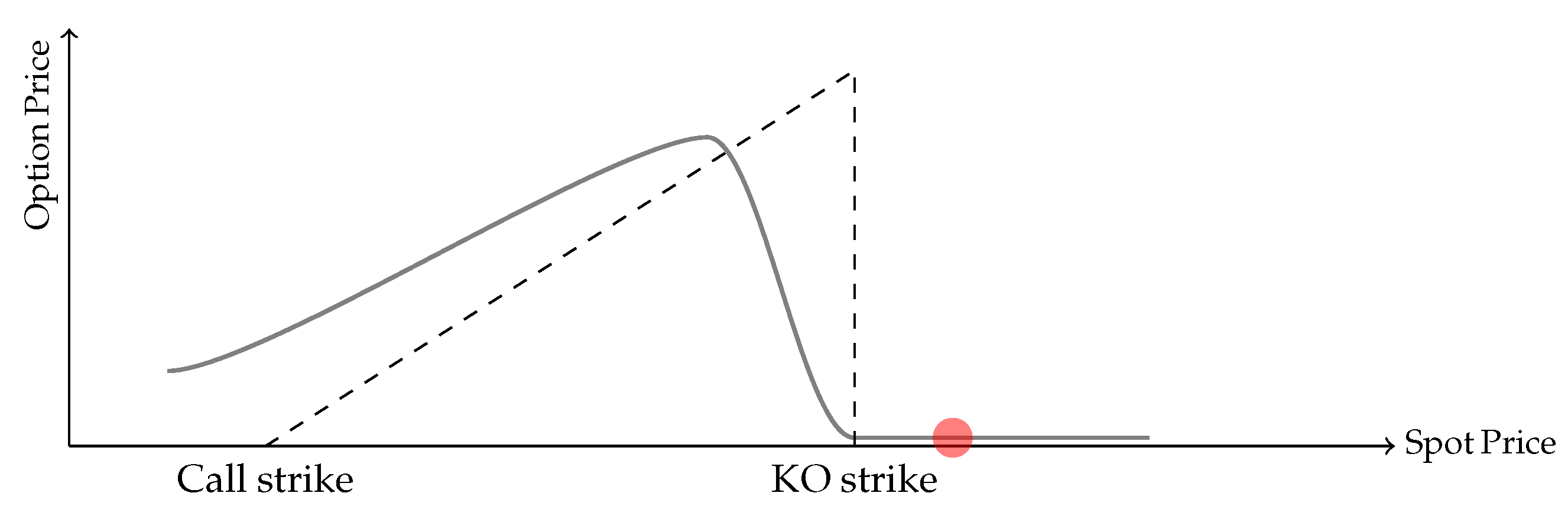

Now, let’s assume the stock price jumps closer to the barrier, but not too close, as illustrated in Figure 2. In this scenario, represented by the red dot moving further up, the stock price increases but still remains below the knock-out barrier. However, this aggressive hedging can drive the stock price closer to the knock-out barrier, potentially breaching it. When the barrier is breached, as shown in Figure 3, the KO condition is triggered, and the option becomes worthless, resulting in no payoff. Example 1 demonstrates how a trader’s hedging actions, dictated by models that do not account for market impact, can unintentionally manipulate the payoff of the option. Recognizing this oversight, risk managers and traders often adapt their strategies to mitigate the inefficiencies of these models.

In practice, traders and risk managers are aware of the potential for unintentional payoff manipulation. To mitigate this, a common heuristic method involves modifying the payoff structure by setting the barrier level slightly above the actual knock-out (KO) strike and shaping the option to behave like a reverse straddle, peaking at the KO strike. This adjustment smooths the payoff near the boundaries and reduces the option’s sensitivity to small movements in the underlying asset, thereby limiting the amplitude of daily delta adjustments required for hedging. By using this approach, traders effectively price and hedge a hypothetical payoff that is more likely to trigger a payment than the true payoff, resulting in selling the option at a higher premium. Although a detailed explanation of this heuristic lies beyond the scope of this paper, it illustrates that the challenges discussed earlier are well recognized in practice, and that practitioners routinely employ such adjustments to market manipulation risks.

2.3. Our Approach and the Ecosystem Studied in This Paper

The example above underscores the necessity for models that account for the market impacts of trading activities and sets some criteria for preventing market manipulation. Central to this is how a large trader’s knowledge of their market impact influences their hedges. To explore how this knowledge influences their actions, we introduce the concept of a hypothetical insider trader. This insider trader possesses the same information as the large trader but does not impact the market because their trades are too small to influence prices. By studying the option pricing and delta hedging strategies of this insider, we gain insights into how information alone, without the market impact, affects pricing and hedging strategies in derivatives trading. This construction parallels the informational component of order-flow dynamics documented in microstructure research, where informed and liquidity-driven trades are distinguished (

Easley & O’Hara, 1996;

Huang & Stoll, 1997), while deliberately excluding the liquidity-driven (mechanical) component of price impact in order to isolate informational effects.

Therefore, we hypothesize a market characterized by limited liquidity, with two types of actors:

1The large trader who has market impact and is aware of the effect of its own actions on the market.

The insider trader who possesses the same knowledge as the large trader but does not generate any market impact because its share execution size is small.

3. The Market Impact Model

We consider a finite, deterministic time horizon . Let be a complete probability space. Let be a standard Brownian motion and be a homogeneous Poisson process with intensity . We assume that the processes and are independent. The probability measure is traditionally called a real-world probability measure. Let be the filtration jointly generated by the processes and .

While leveraging a homogeneous Poisson process for its simplicity and tractability, we acknowledge the limitations this assumption may impose, particularly in more nuanced market contexts where a Cox process, with an intensity that adapts to market conditions and is -adapted, could offer a more refined model. Nonetheless, our focus remains on the homogeneous Poisson process to maintain model simplicity and computational feasibility.

The core of our model revolves around three

-adapted processes: the underlying spot price process

, the process

denoting the annualized rate of shares executed by a large trader, and the process

representing the evolving volume of shares held by the large trader. These processes are governed by the following dynamics:

with

and

. The asset’s drift, represented by

, is assumed to be a deterministic real function, and the constant volatility

is also deterministic.

In Equation (

1),

is a piecewise continuous and bounded function that specifies the

execution speed of the large trader’s orders, denoted by the trading strategy

, where

represents the annualized rate of share execution at time

t. Here we assume that, to conceal its order size, the large trader keeps this strategy hidden from the market; hence,

is known only to the large trader and to the insider trader.

While this goes beyond the scope of this paper, there are various algorithmic methods to conceal order size. The simplest is the price-taker approach, which places market orders that are immediately filled at the best available price. Another common method employs iceberg-type limit orders. See

Christensen and Woodmansey (

2013) for more details.

Moreover,

, a non-decreasing, square-integrable function, encapsulates the permanent market impact of the large trader’s actions, satisfying

. We postulate that during a brief interval

, the market’s liquidity is either sufficient to absorb the trade without any lasting impact or insufficient, leading to a permanent market impact. In scenarios where market liquidity can accommodate the trade volume, the executed orders do not result in a permanent change to the asset’s price. Conversely, when market depth is inadequate, the trading activity induces a permanent market impact, quantified by the function

.

2 This impact is realized at the occurrence of each Poisson jump, where the asset’s price adjustment is directly tied to the instantaneous trading rate.

Note that the market impact could be positive or negative depending on whether the shares are bought or sold. In the case of no trading activity by the large trader, Equation (

1) reduces to the standard Black-Scholes dynamics.

4. Option Pricing for the Insider Trader

The insider trader has access to the information about the trading policy of the large trader over time. Let be a deterministic interest rate process. We also assume that the holder of the stock benefits from a dividend yield of , as well as the presence of a securities lending market and a future market for the underlying stock. The holder of the stock bears a cost of carry b, which is the adjustment rate between the future market and the current value of the stock. These markets, although subject to liquidity issues, enable the holder to enter into short selling positions.

In the following theorem, we demonstrate the existence of a set of probability measures under which the asset price and the option value are martingales. This result is the main outcome of this section and formulates mathematically how the insider trader’s information affects the pricing of derivatives and the hedging strategies.

Theorem 1. Under the regularity condition:the following results hold: - 1.

There exists a set of probability measures where for any measure the returns of the discounted asset are martingales under the measure I.

- 2.

The option price for the insider trader is also a martingale under probability .

- 3.

We call the set of information-neutral probabilities. Then, among all the information-neutral measures, there exists a probability measure that minimizes the quadratic variation of the difference between the hedging portfolio and option value. We call the minimal variation information-neutral probability measure.

- 4.

The discounted return of the asset is a martingale under measure .

Moreover, the dynamic of the spot price under is described by where is a doubly stochastic Poisson process whose stochastic intensity process verifies for each .

- 5.

Furthermore, if the insider trader has entered into a transaction with terminal payoff , we call , the price of this option at time t and spot level S and the net volume of shares hold by the large trader V. Then, for all , the option price can be computed via the following partial differential equation:

Proof is available in

Appendix A. The demonstration of employs quadratic hedging and local risk-minimization techniques, akin to the approach of

Cont and Tankov (

2003);

Föllmer and Schweizer (

1990). Central to this proof is the application of the Girsanov Theorem to both the jump and Brownian processes. This application results in an adjustment of the drift term from

to

for the Brownian motion and modifies the intensity of jumps for the Poisson process. It’s noteworthy that under the conditions where

throughout the interval

or

, the Equation (

5) simplifies to the classical Black-Scholes partial differential equation.

It is worth noting that due to market incompleteness, the condition for the uniqueness of the martingale measure is not satisfied. As further elaborated in

Tankov and Voltchkova (

2009), when jumps coexist with a Brownian motion, the market becomes incomplete. This means that one cannot perfectly hedge all sources of variability using a conventional hedging portfolio comprising the underlying asset and a risk-free instrument. This also indicates the existence of numerous martingale measures.

We refer to Theorem 1 as defining an

information-neutral measure because, for an insider, the market-impact process

is not an exogenous source of uncertainty but a process known to them. Theorem 1 extends the classical risk-neutral change of measure to a probability measure under which, conditional on the insider’s information, the discounted asset price remains a martingale by which the informational advantage is incorporated and then filtered from the drift of the stock dynamics in Equation (

4). This result isolates the informational component of price dynamics from genuine market risk and provides the theoretical foundation for the subsequent pricing and hedging results developed under this framework. By analyzing the market from the insider’s perspective, we capture how informational asymmetry alters the martingale pricing structure.

5. Physical Delivery Option for the Large Trader

In this section, we consider a large trader hedging an option with a terminal payoff of cash and physical delivery of shares. Physical delivery is the most prevalent transaction type for stock options, wherein the buyer receives the underlying asset upon expiration. This differs from cash settlement, where the payoff is settled in cash. For further details on option types and settlement methods, we refer to

Cboe Inc. (

2022).

Definition 1. We define the hedging strategy account by the couplet , with representing the number of shares holding account, and an -adapted process representing the cash account, with as a constant and . The dynamics of these processes are described as follows:where the process represents the transaction costs process by the large trader and is defined by and , where g is a sufficiently regular function (we provide further details on the possible parametric modeling of g in Section 6.2). 5.1. Hedges Trading P&L

Definition 2. We define the P&L of trading activity, noted as , as the product-sum of , which is the number of shares held at time u, and the discounted asset return over the interval : Essentially,

represents the profit-and-loss resulting from delta rebalancing trading activities. Under any information-neutral measure

, the expectation is given by

because the discounted asset price is a martingale under

I.

However, under the historical measure

we may have

If the

is positive in expectation in the historical measure, it suggests that there are dynamic arbitrage opportunities in the market that can be exploited with the right knowledge. This kind of practice is flagged as “abusive squeeze,” as discussed in

Section 2, which manifests when an individual or entity exerts notable control over the supply, demand, or delivery processes of a qualifying or related investment.

5.2. Option and Hedges P&L

Proposition 1. At any time , we define as the accounting value

of the trading activity. The discounted accounting value at the terminal date T satisfies Proof is available in

Appendix A. The left-hand side of (

10) is the discounted value of the portfolio of shares and cash between

t and

T. The right-hand side decomposes this into trading P&L net of execution costs, consistent with the economic structure of a large trader’s hedging program.

Definition 3. We assume a physical delivery European option with an expiry date of T and a settlement date . Hereafter, denotes the terminal number of shares to be either delivered or received, and is the terminal cash transaction.

It is important to recall that represents the quantity of shares held by the large trader at time T. As such, the collective sum of and reflects the remaining shares in the large trader’s account at the terminal date. For effective hedging, and should have opposite signs. Specifically, if is positive, then should be negative, and conversely.

Any residual shares, represented as , need to be executed between the expiry and settlement dates. This execution cost is denoted as . Notably, at time T, the cost associated with executing these shares between T and is considered known. Hence, is -adapted.

To hedge their position, the large trader maintains a portfolio consisting of

in cash and

shares at time

t, using the same notation as in the previous section. Given the high hedging costs, the large trader may opt to leave some positions unhedged, anticipating favorable market movements to offset any potential issues arising from the unhedged portion. The final profit and loss at maturity seen from

t is then given by

Equation (

11) has three main components: the option payoff, the accounting value of the hedging portfolio, and the terminal cost of executing any missing shares between the option expiry time

T and the settlement date

for physical delivery options.

By combining Equations (

10) and (

11), we can obtain the following formulation for the terminal

:

On the right-hand side of Equation (

12), the first component represents the option payoff, and the second term is the profit and loss from trading activities, as defined in Equation (

7), due to changes in the value of the underlying asset during the option’s lifetime. The third term represents the temporary transaction costs of the delta-hedging program, while the last term represents the accounting value of the hedging portfolio at expiry.

5.3. Manipulating the Payoff Constraints and Problem Reduction

The trader’s objective is to ensure that the P&L is non-negative. Without considering market abuse restrictions, the large trader would therefore seek to maximize expected P&L by solving . Two key considerations arise.

First, we must determine under which probability measure the expectation of the P&L should be computed. A natural choice is the historical (real-world) measure, as it reflects actual probabilities. However, as discussed in Section 2, the expected trading P&L, denoted , is not zero under the historical measure. This implies that using the historical measure could introduce an incentive for manipulative strategies, such as squeeze arbitrage. In contrast, under the information-neutral measure, the expected is zero, which is desirable because it ensures that neither the trader nor the model has an informational incentive to influence prices for a higher expected trading profit.

Second, to prevent payoff manipulation, we refine the stochastic optimization problem by excluding the payoff component from Equation (

12). This modification removes any direct incentive to alter the option’s payoff and thereby eliminates one potential source of manipulation.

It is worth noting that these two points are necessary conditions but not sufficient to avoid market abuse. While these measures do not guarantee a market manipulation-proof model, they address essential aspects to minimize the risk of falling into model-induced market abuse.

Specifically, among the information-neutral probability measures, we deploy the minimum variance probability measure, which we developed and defined in detail in the previous section. Consequently, we reduce the problem to Equation (

13), to an optimization of the cost function per share

J acting as its solution:

Equation (

13) consists of two parts: the transaction costs of executing missing shares between the expiry date

T and the settlement date and the transaction costs of executing shares before the expiry date. Both terms act against each other, and the trader needs to strike a balance between buying shares too early and getting closer to a full delta hedge with fewer missing shares to recover in the future but paying extra costs because of executing the shares too quickly, or leaving its position partially unhedged. In the favorable scenario, the market will move in the trader’s direction, and the partial hedge will be closer to the full hedge. Otherwise, the trader will have some time between the expiry date

T and the settlement date

to execute the missing shares. Note that at the expiry date, the number of required shares is fixed and is no longer uncertain.

Theorem 2 establishes the relationship between the cost function

J and the partial differential equation (PDE) that governs it. The theorem states that

J can be deduced from the PDE expressed in Equation (

18), subject to the terminal condition in Equation (

19).

Theorem 2. Let denote the cost-per-share value function associated with (13). - 1.

Define the Radon–Nikodym density and introduce the probability measure byUnder , the Brownian motion and jump intensity satisfyand the stock price dynamics becomewhere is a doubly stochastic Poisson process with intensity . Changing numéraire from to the discounted stock measure transforms (13) into the reduced cost-per-share representation - 2.

The value function satisfies the Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation For any admissible control χ, the running cost contribution is and the optimal running term is The optimal execution rate is therefore

Proof is available in

Appendix A. It is important to note that

are dependent on

.

6. Numerical Results

In this section, we present numerical results focusing on the large trader hedging an out-of-the-money call option. We analyze the option costs, hedging dynamics for the large trader, and the implications for the insider trader. Additionally, we perform a sensitivity analysis on key model parameters.

6.1. Solving the Partial Differential Equations

To numerically solve the two-dimensional partial differential Equation (

18), we can use the dynamic programming approach described in Algorithm 1. First, we initialize the cost function

to the terminal condition

at the expiration time

T. Then, we discretize time into

intervals and iterate backward in time from

T to 0, updating

at each time step using Equations (

18), (

20) and (

21). We repeat this process for

n iterations to ensure convergence.

Once we have obtained the optimal hedging strategy

, we can use it to solve for the insider’s trader option price

using a finite difference scheme for the partial differential in Equation (

5). Finally, we obtain the values of

and

at time 0, denoted by

and

, respectively. More details on the finite difference scheme used to solve Equation (

18) are provided in the

Appendix A.

| Algorithm 1: Methodology for solving the large trader’s cost function |

- 1:

; - 2:

Discretize the time to intervals; - 3:

for

do - 4:

Using apply Equation ( 21) and solve ; - 5:

Using , apply Equation ( 20) and calculate ; - 6:

Using , solve Equation ( 18) and obtain .; - 7:

for do - 8:

Using apply Equation ( 21) and solve ; - 9:

Using , apply Equation ( 20) and recalculate ; - 10:

Using , solve Equation ( 18) and obtain ; - 11:

end for - 12:

Given , solve the insider’s trader option price using a finite difference scheme of the partial differential in Equation ( 5); - 13:

end for - 14:

Obtain and

|

Note that, to solve

in Equation (

5) as well as in Equation (

18), we employ a numerical scheme similar in structure to those used for path-dependent (e.g., Asian) options. The algorithm executes a set of two-dimensional finite-difference schemes in parallel—each corresponding to a discretized level of the grid, the net volume of shares held by the large trader. In each step, the PDE for

is first solved independently across all grid-levels, and a subsequent semi-Lagrangian remapping stage integrates the impact of changes across the grid. This approach alternates between the diffusion dynamics in

and the advection dynamics within the grid. A detailed presentation of this well-established method can be found in

Rogers and Shi (

1995).

From a computational point of view, the overall complexity of the numerical scheme scales linearly in each of the three discretization dimensions. At every time step, the implicit finite–difference solve in the dimension requires, for each of the values of V, the construction of a tri–diagonal matrix and the solution of a tri–diagonal linear system of size . Since a tridiagonal matrix algorithm is used, each such solve costs operations, yielding a total PDE cost of per time step. The optimization step that computes involves a directional search at each grid node ; because this search is local and terminates after a small number of updates, its total cost per time step remains . The semi–Lagrangian reorganization of the grid, which updates the solution according to the shift induced by V, also loops once over the entire grid and therefore contributes another operations per step. Summing all stages over the time steps of the backward induction, the total computational cost of the method is which reflects linear scaling in the spot discretization, the volume discretization, and the number of time steps.

6.2. Choice of Transaction Costs Parametrization

We first need to define a parameterization for the transaction costs function. Let

be a stochastic process with the dynamics defined by Equation (

23). The process

represents the transaction costs beared by the large trader:

where

is the (annualized) average volume,

is the impact factor, and

is the exponential factor. The form is consistent with the empirical microstructure literature, in which marginal execution cost grows sublinearly with trade size, commonly approximated by square-root or other concave laws (

Almgren et al., 2005;

Grinold & Kahn, 2000;

Zarinelli et al., 2015). For longer periods between the expiry and settlement date, an optimal purchase/liquidation algorithm can be applied, as explored in the literature (e.g.,

Almgren and Chriss (

2001)). However, in this study, we use a constant rate program for simplicity. In this case, the expected value of function

—the terminal cost of executing

x at time

between the expiry and settlement—can be expressed as Equation (

24) below.

Proposition 2. Assume the trader needs to execute X shares within a period of τ and chooses to do so at a constant execution speed of .3 Moreover, we assume that there are no dividends and lending costs during the time period from T to . Under these conditions, the expected value of the cost under an information-neutral measure is described by the following equation: Proof is available in

Appendix A. Overall, our cost model allows to capture the trade-off between the size of the trade

and the time until the settlement date

. Specifically, as

x increases, so does the cost of execution, but at a decreasing rate governed by the exponent

. In contrast, as

increases, the cost of execution decreases due to the larger time frame for trading. These properties parallel empirical observations that execution cost rises with urgency and notional size, but at a diminishing marginal rate.

6.3. Out of the Money Call Option

In this section, we present numerical results for a large trader who is the seller of a call option defined in

Table 1.

We also make the hypothetical parameter assumptions as per

Table 2. These assumptions, though hypothetical, fall within the realistic ranges commonly used in financial modeling and empirical studies. The annual drift rate,

, is within the range of U.S. annual returns of small-cap stocks as documented by

Damodaran (

2025). The volatility parameter,

, aligns with the historical range of the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX), which typically fluctuates between 10 and 20 during stable markets and exceeds 30 during periods of high market stress

VIX (

2025). The risk-free rate,

, reflects the low-interest-rate environment observed in the U.S. market during 2010–2020. Also, further in this section, we will provide sensitivity testing to the choice of parameters

,

, and

. Finally, for simplicity, we assume that the stock does not pay any dividends (

) and its lending yield is zero (

).

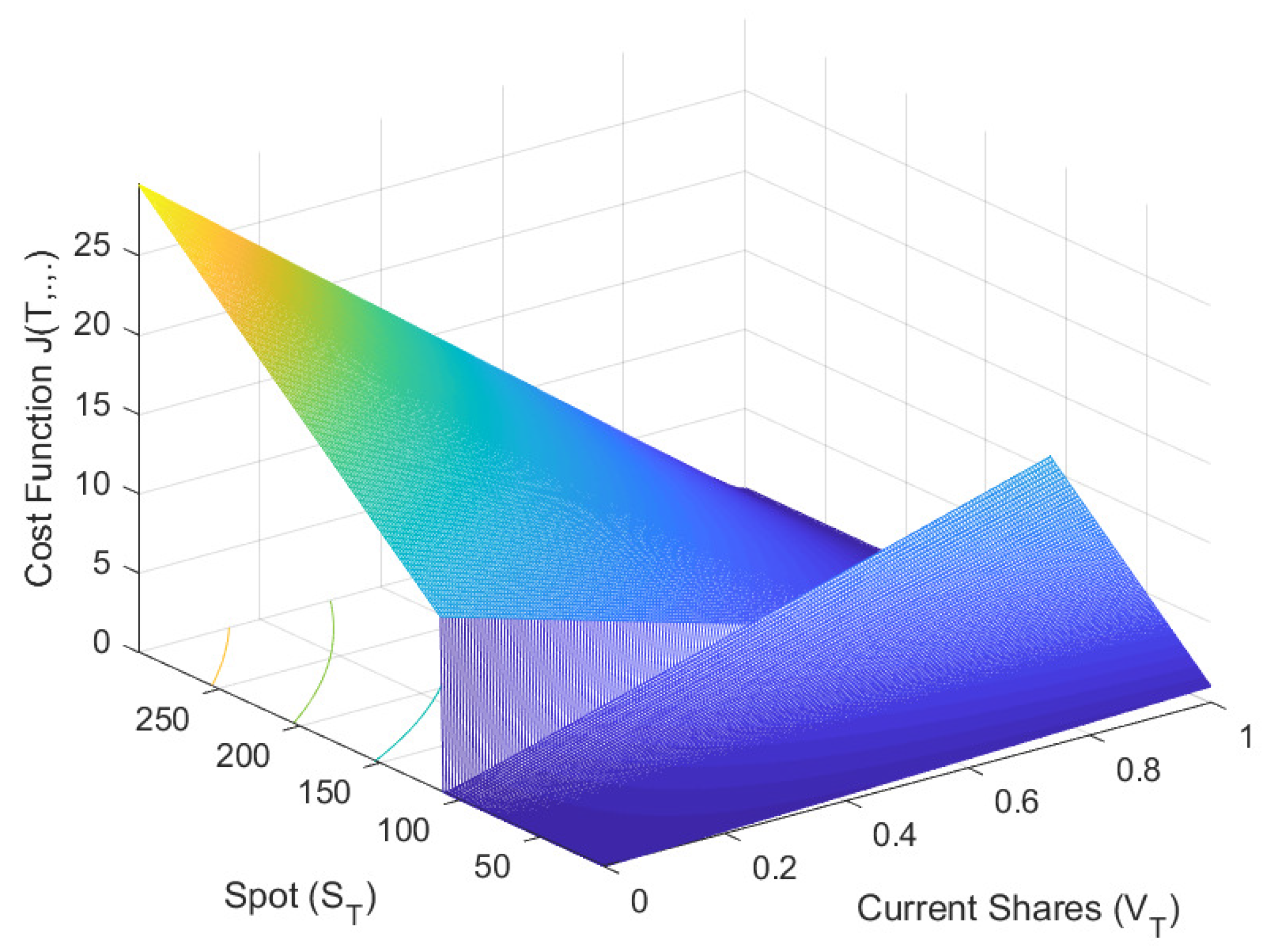

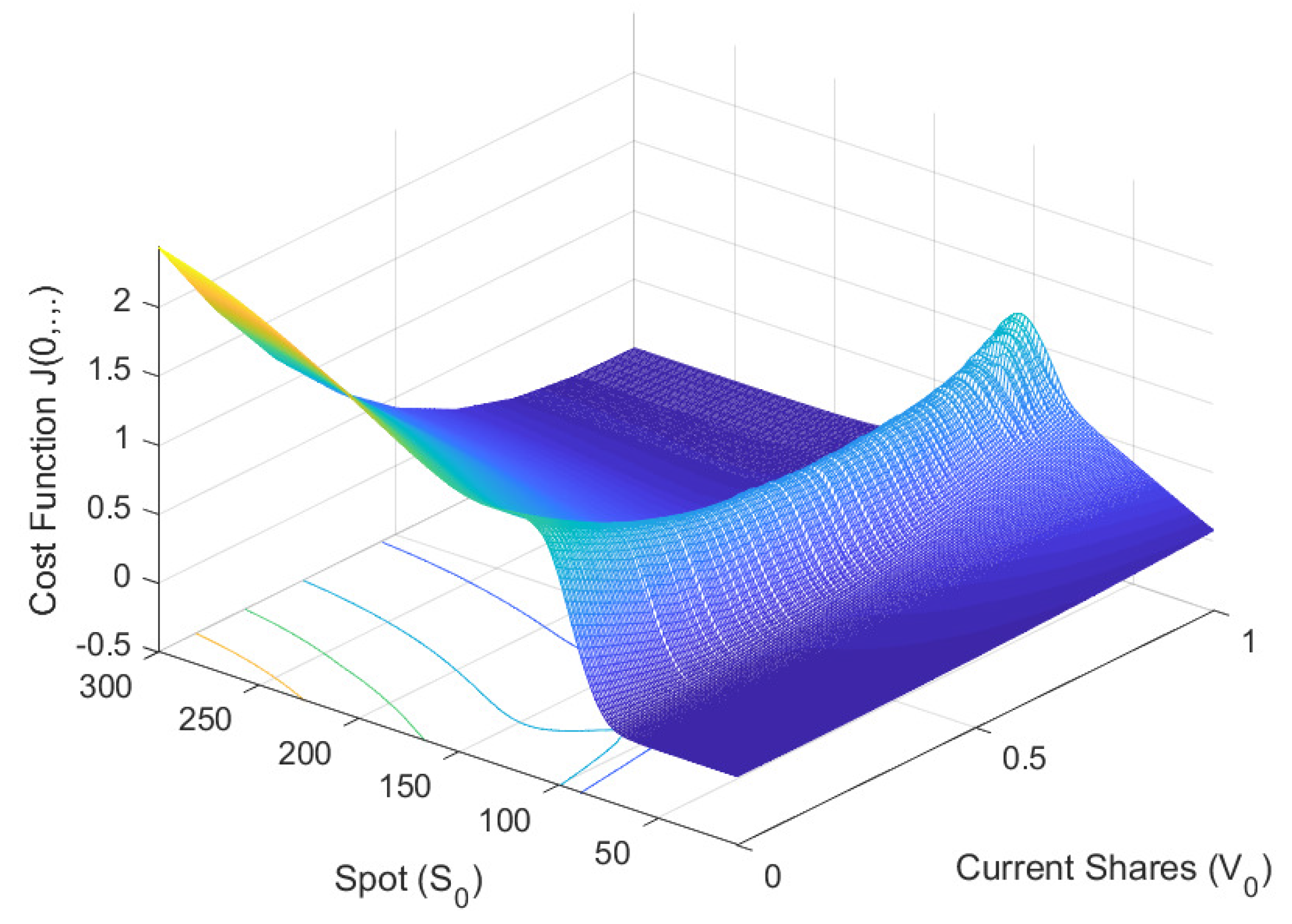

Figure 4 depicts the terminal cost function

J for the large trader’s call option. The graph illustrates different scenarios depending on the final stock price and the number of shares

to be delivered at expiration. When the option is in the money, i.e., the stock price is above the strike price, the cost function is zero since the large trader delivers the shares at no additional cost. Conversely, when the option is out of the money, i.e., the stock price is below the strike price, the large trader needs to purchase the notional amount of shares before the settlement date, leading to higher costs. As shown in the graph, the cost function varies across different corners but gradually flattens as we move backward in time, as observed in

Figure 5. These results are consistent with our cost model in Equation (

19), which assumes a linear relationship between the cost and the spot price of the stock. These properties parallel empirical findings that market impact increases with order size and urgency, but with a concave (diminishing marginal) dependence (

Almgren et al., 2005;

Zarinelli et al., 2015).

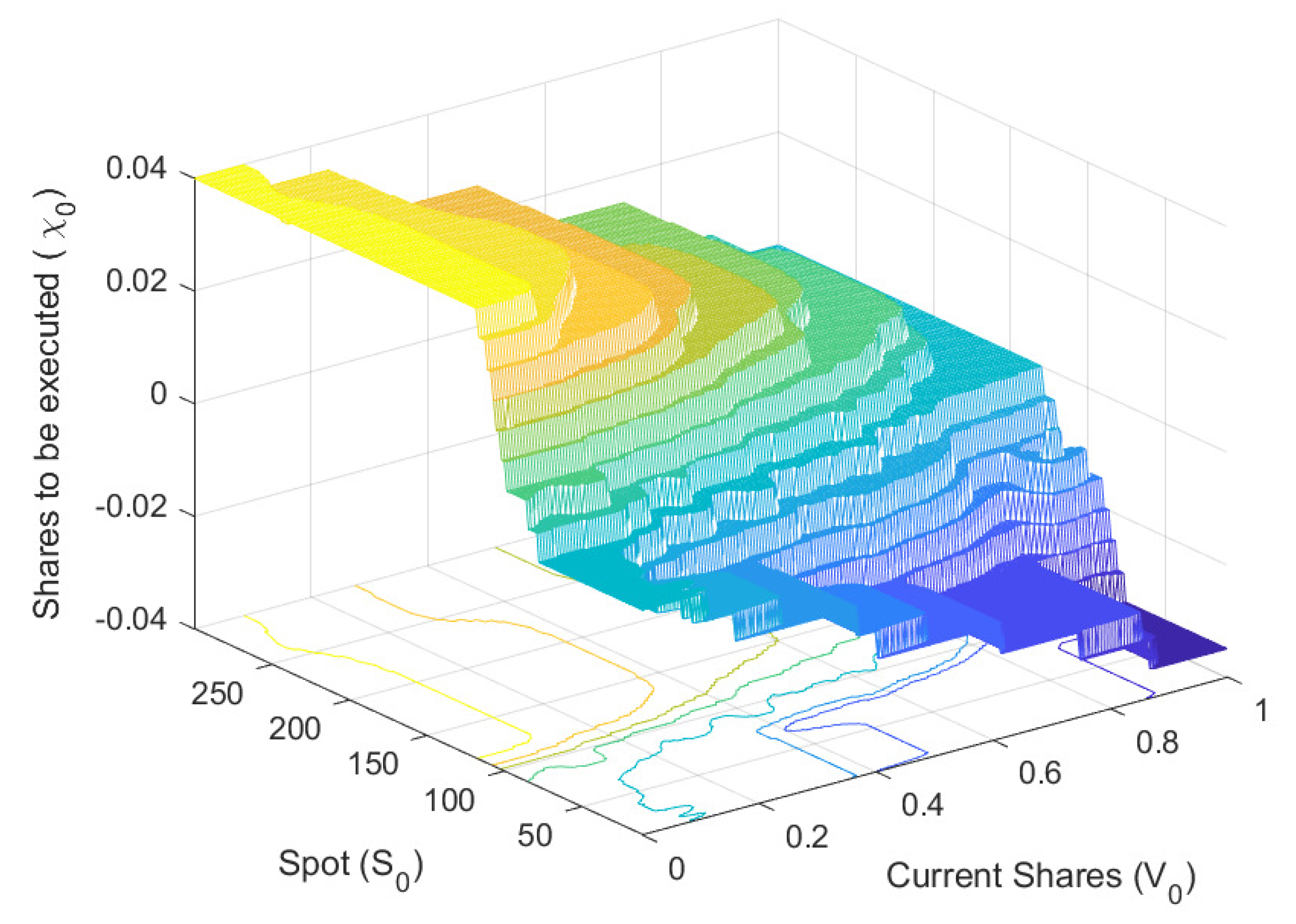

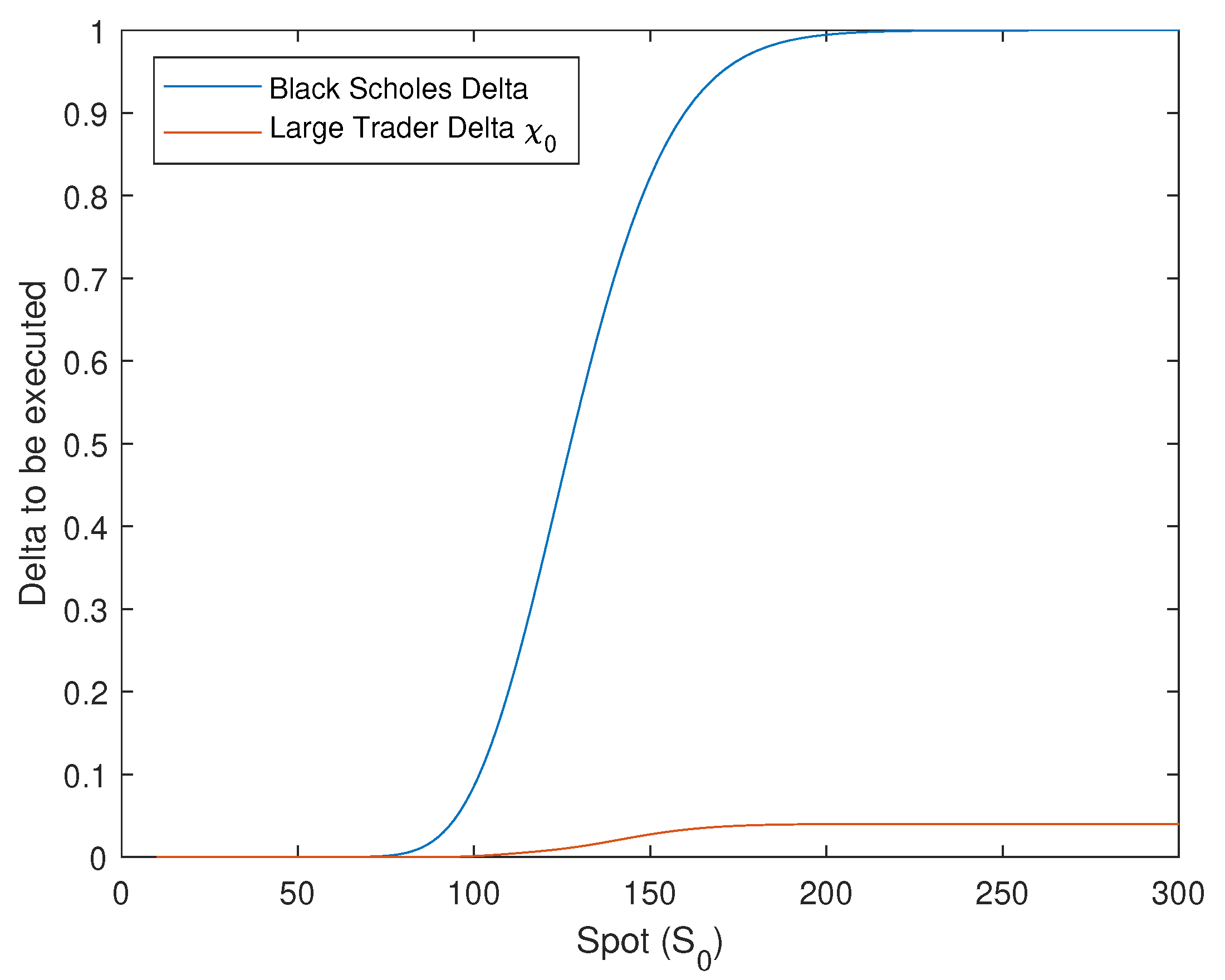

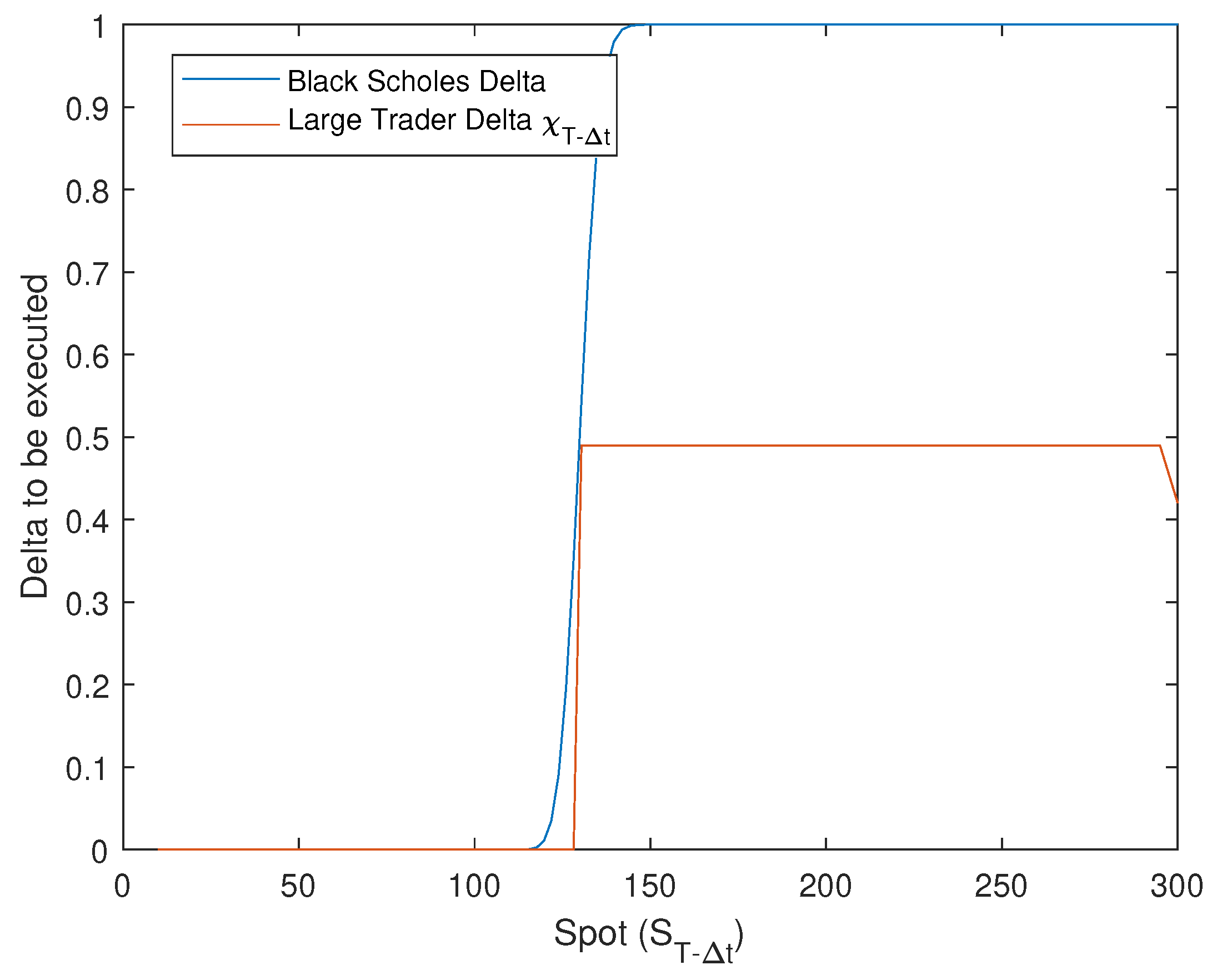

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the optimal amount of shares to be executed (

) at time 0 and just before expiry, respectively. Our findings suggest that the optimal

is much lower than the Black-Scholes Delta due to the high cost of a full hedge strategy. As shown in

Figure 8, the difference in Delta between the two strategies is significant. The large trader executes only a small percentage of

at time 0, whereas the Black-Scholes Delta is 100% for the same spot levels. However, as the expiry date approaches, the large trader’s optimal strategy gets closer to the Black-Scholes Delta, as illustrated in

Figure 9. This muted hedging intensity aligns with empirical evidence that large institutional traders hedge less aggressively than theoretical deltas because of market impact constraints (

Abergel & Loeper, 2017;

Kraft & Kühn, 2011).

Examining the impact of the large trader’s hedging strategy on the insider trader’s option price, as defined in

Table 3, provides valuable insights.

Figure 10 compares the insider trader’s option price with the Black-Scholes model for the same call option. The graph highlights the option’s increased convexity around the money and the higher prices than the Black-Scholes model when the option is in the money, surpassing even the intrinsic value. This phenomenon is due to the directional market impact of the large trader. If the spot price is in the money, the large trader will purchase shares, driving the spot price deeper into the money. The insider trader’s option price, therefore, reflects the market impact of the large trader, resulting in a higher option price than predicted by the standard Black-Scholes model. This upward deviation is consistent with empirical price-pressure effects documented in transaction-level studies (

Hasbrouck, 1991).

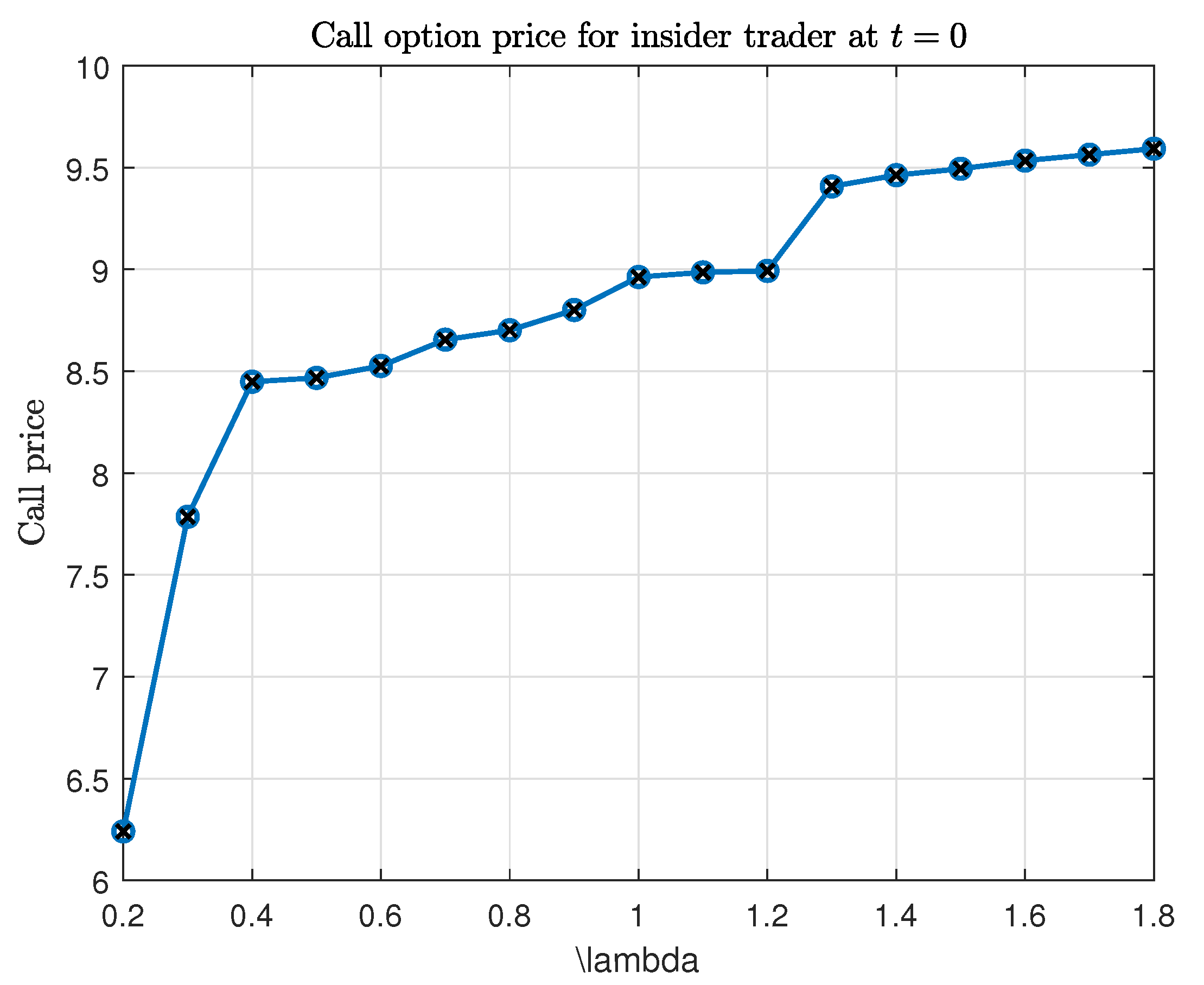

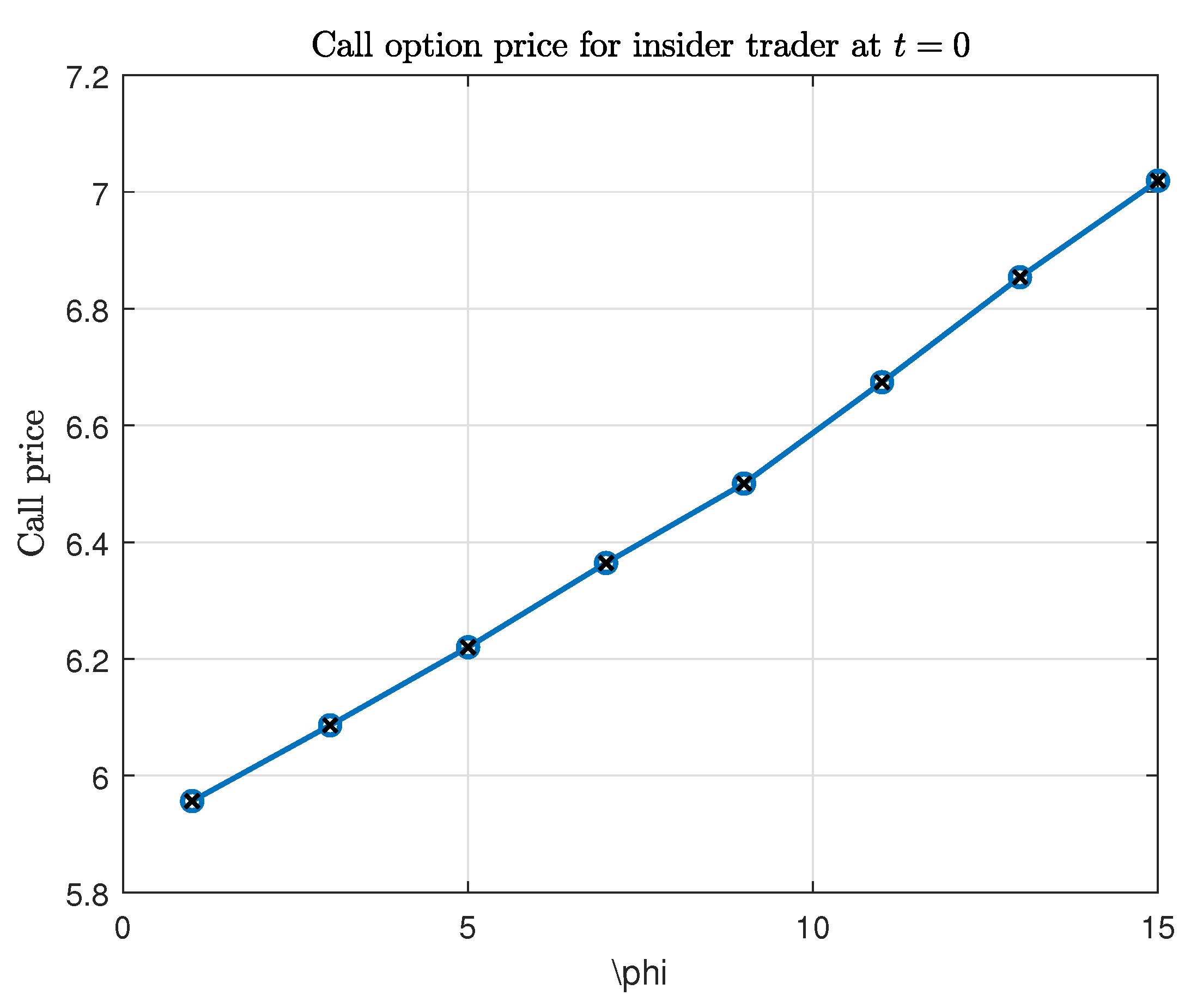

We would also like to highlight the fact that the insider option price is sensitive to parameters

,

,

as shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. Economically speaking, an increase in the market impact parameters

and

results in a higher call option price for the insider trader (for the option defined in

Table 1). Recall that

is the market impact factor, and

is the frequency of the market impact function. Higher values of these two parameters result in a higher market impact function and, accordingly, more divergence from the Black & Scholes price. These sensitivities resemble empirical relationships between participation rate, execution frequency, and permanent impact reported in equity microstructure (

Almgren et al., 2005), with the additional touch that in here we study the price of a convex payoff, i.e., a call option (

Cetin et al., 2006).

7. Discussion, Limitations and Further Research

While the model presented here is conceptually sound, it is worth acknowledging several shortcomings and directions for further research. These limitations also suggest how the framework may speak to broader questions in market microstructure, particularly concerning the interaction between informed trading, mechanical price impact, and liquidity fluctuations.

First and foremost, we have not proven mathematically that the model presented in this paper is non-manipulative. This challenge exists because, as of the date of this paper, market manipulation—and specifically payoff manipulation—has no formal mathematical definition to refer from which such a proof could be derived. This is potentially because any mathematical definition of manipulation would need to depend on the legal definition. The legal definition, however, has turned out to be subject to judicial interpretation, as illustrated by

Fletcher (

2018), which provides examples of differing legal interpretations.

Curato et al. (

2017) also note that defining manipulation in a mathematically consistent and empirically valid way remains an open problem. A similar challenge arises in the microstructure literature, where empirical evidence of settlement distortions and price-pressure effects (

Griffin & Shams, 2018;

Ni et al., 2005) has not yet produced a unified theoretical definition of manipulation. In short, before we can claim that a model is non-manipulative, two prerequisites are needed: (i) a legal definition that minimizes subjective interpretation and (ii) a general mathematical theory of market manipulation for derivatives. Developing such a general theoretical framework is outside the scope of this paper, but with the proposed method—which models the problem from the standpoint of an informed trader—we can assert that, through this framework, the large trader becomes effectively blind to the market impact of its own hedging activity. This method may prove useful for future research on formalizing market manipulation mathematically. In particular, the information-neutral construction proposed here may serve as a building block for microstructure models that explicitly separate informational asymmetry from mechanically induced price impact, in the spirit of

Glosten and Milgrom (

1985) and

Hasbrouck (

1991).

For completeness, we note that our market-impact specification also relates to a second strand of the market microstructure literature concerned with dynamic no-arbitrage and round-trip trading strategies. Classical results by

Huberman and Stanzl (

2004) and

Gatheral (

2010) show that permanent price-impact functions must satisfy linearity conditions to preclude profitable round trips. Furthermore,

Guéant (

2013) proved that other forms of market impact, which are not linear, also conform with the no-arbitrage condition. Although we do not include a full technical development here for reasons of conciseness and to maintain focus on the information-neutral framework, we verified that—under linear permanent impact—the Poisson permanent-impact specification used in this paper is consistent with these no-dynamic-arbitrage principles in the sense that round-trip trading does not yield positive expected P&L under certain condition.

Also, some of the intricacies of our model relate to the specification of the market-impact function, as summarized below:

The permanent-impact model presented in Equation (

1) operates at

random times, contrasting with deterministic formulations such as

Almgren and Chriss (

2001).

4 This randomness is plausible in markets with stochastic liquidity, as proposed in recent studies (

Almgren, 2012;

Barger & Lorig, 2019;

Klöck, 2012;

Ma et al., 2020), and our model follows this line of research while leaving empirical validation of stochastic market-impact functions for future research.

Another advantage of a stochastic market-impact specification is that this component of the underlying spot process becomes part of its

quadratic-variation term. If the impact were deterministic, it would enter the model at the same order as the drift. By introducing randomness, however, the market-impact term contributes directly to the volatility of the underlying asset. This modeling choice motivates a potential line of investigation: if market volatility arises primarily from the market impact of demand–supply imbalances, then the impact function itself should be of the same stochastic order as volatility. This idea is consistent with empirical evidence that short-term volatility is closely tied to order-flow imbalances and liquidity fluctuations (

Bouchaud et al., 2004;

Hasbrouck & Seppi, 2001). A natural extension would be to examine whether the information-neutral decomposition proposed here is borne out in transaction-level data.

Apart from the stochastic nature of market impact, our model assumes a Poisson jump process. This choice introduces discontinuities, representing periods with no jumps as times when market depth is sufficient to absorb trades without permanent impact. In practice, however, large transactions rarely exhibit such intervals. Alternative continuous-time formulations, such as exponential or Lévy-based specifications, could capture this behavior more realistically. Exploring these alternatives constitutes a promising avenue for future mathematical research.

Another limitation of a pure-jump specification is that when the jump intensity

is large—as in our model, where frequent market-impact events are intended—the Poisson process begins to approximate a one-sided continuous motion. This behavior increases numerical error in the PDE simulations, since the jump component is handled separately from the tridiagonal scheme used to solve the drift–diffusion part of the equation, see

Abeille et al. (

2023). From a microstructure perspective, understanding such numerical effects may be relevant for modelling high-frequency impact dynamics where order flow arrives in rapid bursts (

Curato et al., 2017).

Another assumption in our market impact model is the absence of a correlation between the stochastic liquidity process

and other external sources of spot volatility

. In practice, days with higher volatility are often associated with greater challenges in executing stock trades without significantly impacting the market. A more realistic model might assume some degree of correlation between

and

. This correlation is consistent with empirical evidence that periods of elevated volatility are associated with reduced liquidity supply, as documented in

Chordia et al. (

2001).

Lastly, one may observe that this paper provides a theoretical price for the insider trader but does not explicitly define a price for the large trader. In martingale asset–pricing theory, the price of a contingent claim is obtained as the expected value of its discounted payoff under a martingale measure. The martingale measure used here is the minimal-variance information-neutral measure, constructed based on the insider’s hedge , which is accessible to the insider because such a trader can execute it.

The situation differs for the large trader. The large trader hedges through the process

, not

. Therefore, the trading strategy of the large trader does not fully replicate the payoff, and no arbitrage-free “large-trader price” can be derived. Instead, we evaluated the expectation of temporary cost function, denoted

, under

as perceived by the insider, and determine an admissible hedging policy

based on that. The existence of an information-neutral martingale measure that is also accessible to the large trader remains an open question and is left for future research. If such measure exists, it can be then used also for obtaining the admissible hedging policy

.

5 8. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper examines the implications of a large trader’s activities on option pricing and hedging. We addressed an important but overlooked problem in the literature: how a large trader’s knowledge of their own trading activity can influence their actions. Therefore, a key contribution of this paper is its methodology to disentangle this knowledge from other factors influencing options’ hedging strategies.This separation between informational and mechanical components of order flow places the analysis squarely within the market microstructure literature, where this distinction plays a central role. To achieve this, we introduced the concept of an insider trader, who has the same information but does not impact the market.

Our analysis established the existence of information-neutral probability measures, under which the discounted asset prices are martingales for the insider trader. Using these information-neutral measures, along with necessary conditions for mitigating market manipulation, we derived a cost optimization function to establish a hedging policy for the large trader. This framework allows us to develop a hedging policy that accounts for transaction costs and market impact while taking into account some conditions for non-manipulative practices. These findings offer a practical and effective approach to pricing derivatives under market impact, which can be readily implemented by practitioners. In this respect, the framework contributes to the microstructure literature on large-trader models, permanent impact, and manipulation-resistant execution.

The paper concludes with numerical results that showcase the optimal delta-hedging strategy for an out-of-the-money call option. Our analysis indicates that the model proposes a more relaxed delta-hedging strategy compared to the Black and Scholes model. Additionally, the price of the call option for the insider trader is observed to be higher under market impact than the Black and Scholes model. These numerical patterns align with empirical findings in market microstructure, on price-pressure effects, and drift induced by directional order flow, and complement how this could impact option prices.

Although the analysis was developed under the assumption of a single large trader, several of our findings extend to environments with multiple strategic traders, provided that the insider trader can observe or infer their aggregate impact. Likewise, the construction of the information-neutral measure is not tied to the specific hedging objective studied here and can be adapted to other trading strategies. Future research may explore these extensions in greater depth, especially in settings where systemic behavior arise among different classes of large traders pursuing non-derivative trading strategies. In addition, the framework suggests several further directions for market microstructure research, including extension to multi-agent settings where several large or informed traders interact through liquidity constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and K.B.; Methodology, B.A., K.B. and A.E.; Software, B.A.; Validation, B.A., K.B. and A.E.; Formal analysis, B.A.; Investigation, B.A., K.B. and A.E.; Data curation, B.A.; Writing—original draft, B.A.; Writing—review & editing, B.A., K.B. and A.E.; Visualization, B.A.; Supervision, K.B. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest related to this paper from the authors.

Appendix A. Proofs

Proof of Theorem 1. By Itô formula applied to a process with jumps, the option price dynamics are given by

where

is the jump in the price of the option due to large traders’ activity

, and

is the continuous part of the spot movement.

On the other hand, the insider trader’s option hedging portfolio at time

t is given by

where the insider trader has

in shares and

in cash amount. Given that the notional is small, the insider trader—contrary to the large trader—can hedge its position without additional transaction costs. The dynamics of the portfolio

are as follows:

In our incomplete market, the option cannot be perfectly hedged by a self-financing portfolio. Therefore, we search for a hedging strategy that satisfies the following properties:

: If the market is complete, it is possible to find such that the quadratic variation is always zero. However, this is impossible due to the jump component of the market impact. One can only find a strategy that minimizes the quadratic variation, but it will not neutralize it.

The stochastic part of

can be formulated as:

Therefore, the quadratic variation of

reads as follows:

The insider trader minimizing the quadratic variation will obtain the following formula:

: The average (first order) option price movement is fully hedged by the portfolio.

We can derive the following partial differential equation:

On the other hand, we have

Combining the two equations above with Equation (

A1) we obtain that:

Let’s define the variable

, which represent a jump intensity, as

We also assume the regularity condition (

2) holds. This condition is necessary as otherwise

will not be positive almost surely, and the Feynman-Kac theorem could not be applied as the intensity of the Poisson process will not be positive.

Since this is not a self-financing portfolio, the trader can intervene at each time step by injecting or depleting cash to ensure that the hedging portfolio’s value matches the theoretical value of the option. Mathematically, the trader will inject

in cash into the hedging portfolio, ensuring that

. Therefore, due to these cash injections, the hedging portfolio’s value is continuously adjusted to equal the option price. Based on the definition of

and the assumption that the hedging portfolio is adjusted to satisfy

, we obtain:

Having the partial differential equation above, the most common technique would be to use the Feynman-Kac formula. However, the stochastic process derived is not an exponential Levy, so one has to be careful in using the Feynman-Kac technique for non-exponential-Levy processes. Using the Feynman-Kac formula, the equivalent stochastic equation for the spot price

under a probability measure that we call minimal-variance information neutral probability and note it as

is given by

where

is a doubly stochastic Poisson process with stochastic intensity process

. Also, the following equations hold under the

probability:

To validate our use of the Feynman-Kac technique, we prove that having the stochastic process of Equation (

A5) and the function

of Equation (

A7) would result in the partial differential equation in (

A4).

On the one hand, based on Equation (

A7), we have

On the other hand, applying Itô’s lemma to the function

:

where

is the continuous part of the diffusion of

S in the dynamics (

A5). Now, expanding the dynamics of (

A5) in (

A8) and (

A9), we obtain again the partial differential Equation (

A4). Therefore, our usage of the Feynman-Kac technique was valid.

Note that we have proved the existence of at least one element in the set of information-neutral probability measures, which is the . The existence of is sufficient proof for the existence of the set of information neutral measures and the fact that it is not empty. □

Proof of Proposition 1. Let

denote the discount factor at time

t with maturity

T. or the zero coupon bond price,

the discounted cash

, and

the discounted asset. Therefore:

On the other hand, given the fact that

—defined in Equation (

6)—is a finite variation process, we do have the following equation:

Let’s now call

, then one can write:

Taking the integration, we obtain:

which ends the proof of Proposition 1. □

Proof of Theorem 2. We assume

. Under the measure

, the stock price

satisfies

where

is the

—compensated doubly stochastic Poisson process with intensity

.

The discounted stock

is a strictly positive local martingale under

. Hence

is a positive

—martingale, which defines the measure

via (

14). By the Girsanov–Esscher theorem for semimartingales with jumps, the Brownian motion and intensity under

are given by (

15), and substituting these into the

–dynamics yields:

where

has intensity

.

Starting from the original definition of

J in (

13) and using the standard change-of-numéraire identity with the stock as numéraire,

we divide the original objective by

and obtain the representation (

17) under the stock-numéraire measure

:

Now fix

t and consider a small time step

. From (

17), we have:

where

.

We apply Itô’s formula with jumps to

under the stock dynamics (

16). Over

and for a fixed control

we obtain

where we use the shorthand

,

,

, and

. From (

16) and taking

in (

A14), we obtain

where we have written

and

for brevity.

Substituting this into (

A14), subtracting

from both sides, dividing by

, and letting

yields

with the terminal payoff

, which completes the proof. □

Proof of Proposition 2. Having Equation (

23) for the short-term cost, and with the strong assumptions that all shares requested will be executed, the long-term cost of execution of

X shares in

time is

Note that in our case,

is the constant execution rate. In case we have Equation (

23) for the short-term cost, the long-term cost of execution is as follows:

□

Notes

| 1 | There are other types of traders such as average traders who are too small to influence the market and are unaware of the large trader’s activities. However, this group of traders is not the focus of this paper. |

| 2 | In Equation ( 1), the size of the jump is denoted by , as opposed to . The notation is typically used to ensure the validity of the closed-form exponential representation of the process , which is a product of the impact of all jumps and the exponential Gaussian process, as detailed in Doléans-Dade ( 1970). In simpler terms, for the exponential formulation to hold, jumps need to be applied first to the spot price early at , followed by other sources of variation. However, in our model, an exponential expansion is not employed. From a financial perspective, this implies that while the jump increments are applied to the price at before other variations, its actual magnitude is determined at time t, not at . |

| 3 | While optimal purchase/liquidation algorithms for longer purchase periods are well-researched topics, as seen in works like Almgren and Chriss ( 2001), our focus here is on the constant rate program. There are compelling reasons for selecting a constant purchase program over a more intricate one. Notably, most derivatives desks do not prioritize optimizing their execution cost, placing greater emphasis on volatility instead. Thus, even if optimal algorithms are available, they might not be employed in derivatives trading. Our goal here is not to suggest how the purchasing should be executed but to understand the behavior in the most prevalent scenario. This reasoning drives our choice for a constant rate program. |

| 4 | Later, Gatheral ( 2010) proved that linearity of the permanent-impact function is a sufficient condition for no-arbitrage, while Guéant ( 2013) and others explored nonlinear and stochastic extensions. |

| 5 | A practitioner, however, may form a proxy valuation by combining the insider’s informational price with the large trader’s expected cost, but this is a heuristic and does not constitute an arbitrage-free price. |

References

- Abeille, M., Bouchard, B., & Croissant, L. (2023). Diffusive limit approximation of pure-jump optimal stochastic control problems. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 196(1), 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abergel, F., & Loeper, G. (2017). Option pricing and hedging with liquidity costs and market impact. In Econophysics and sociophysics: Recent progress and future directions (pp. 19–40). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Almgren, R. (2012). Optimal trading with stochastic liquidity and volatility. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics, 3(1), 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almgren, R., & Chriss, N. (2001). Optimal execution of portfolio transactions. Journal of Risk, 3, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almgren, R., Thum, C., Hauptmann, E., & Li, H. (2005). Direct estimation of equity market impact. Risk, 18(7), 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Amendinger, J., Imkeller, P., & Schweizer, M. (1998). Additional logarithmic utility of an insider. Stochastic Processes and Their Applications, 75(2), 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, M. J., & Warner, J. B. (1993). Stealth trading and volatility: Which trades move prices? Journal of Financial Economics, 34(3), 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, W., & Lorig, M. (2019). Optimal liquidation under stochastic price impact. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance, 22(2), 1850059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F., & Scholes, M. (1973). The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordag, L. A., & Frey, R. (2008). Pricing options in illiquid markets: Symmetry reductions and exact solutions. In Nonlinear models in mathematical finance: New research trends in option pricing (pp. 103–129). Nova Science Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchaud, J.-P., Farmer, J. D., & Lillo, F. (2010). How markets slowly digest changes in supply and demand. In T. Hens, & K. R. Schenk-Hoppé (Eds.), Handbook of financial markets: Dynamics and evolution (pp. 57–160). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchaud, J.-P., Gefen, Y., Potters, M., & Wyart, M. (2004). Fluctuations and response in financial markets: The subtle nature of “random” price changes. Quantitative Finance, 4(2), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cboe Inc. (2022). Equity options product specifications. Available online: https://www.cboe.com/exchange-traded-stock/equity-options-spec (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Cetin, U., Jarrow, R., Protter, P., & Warachka, M. (2006). Pricing options in an extended Black–Scholes economy with illiquidity. Review of Financial Studies, 19(2), 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordia, T., Roll, R., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2001). Market liquidity and trading activity. Journal of Finance, 56(2), 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H. L., & Woodmansey, R. (2013). Prediction of hidden liquidity in the limit order book of GLOBEX futures. The Journal of Trading, 8(3), 68–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cont, R., & Tankov, P. (2003). Financial modelling with jump processes. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Curato, G., Gatheral, J., & Lillo, F. (2017). Optimal execution with non-linear transient market impact. Quantitative Finance, 17(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, A. (2025). Historical returns on stocks, bonds and bills—United States. Available online: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histretSP.html (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Doléans-Dade, C. (1970). Quelques applications de la formule de changement de variables pour les semimartingales. Zeitschrift für Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie und Verwandte Gebiete, 16, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (1996). Liquidity, information, and infrequently traded stocks. Journal of Finance, 51(4), 1405–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and of the Council. (2014). Regulation (EU) No 596/2014 on market abuse (market abuse regulation). European Parliament and of the Council. [Google Scholar]

- Eyraud-Loisel, A. (2013). Quadratic hedging in an incomplete market derived by an influential informed investor. Stochastics an International Journal of Probability and Stochastic Processes, 85(3), 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Conduct Authority. (2005). FCA handbook: MAR 1.6.15 market abuse. Financial Conduct Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, G. G. (2018). Legitimate yet manipulative: The conundrum of open-market manipulation. Duke Law Journal, 68, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Föllmer, H., & Schweizer, M. (1990). Hedging of contingent claims under incomplete information. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. [Google Scholar]

- Gatheral, J. (2010). No-dynamic-arbitrage and market impact. Quantitative Finance, 10(7), 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatheral, J. (2012). Transient linear price impact and Fredholm integral equations. In J.-P. Fouque, & J. Langsam (Eds.), Representing, measuring and managing systemic risk (pp. 309–321). World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Glosten, L. R., & Milgrom, P. R. (1985). Bid, ask and transaction prices in a specialist market with heterogeneously informed traders. Journal of Financial Economics, 14(1), 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. M., & Shams, A. (2018). Manipulation in the VIX? Review of Financial Studies, 31(4), 1377–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinold, R. C., & Kahn, R. N. (2000). Active portfolio management. McGraw Hill New York. [Google Scholar]

- Grorud, A., & Pontier, M. (1998). Insider trading in a continuous time market model. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance, 1(03), 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéant, O. (2013). Permanent market impact can be nonlinear. arXiv, arXiv:1305.0413. [Google Scholar]

- Guéant, O., & Pu, J. (2017). Option pricing and hedging with execution costs and market impact. Mathematical Finance, 27(3), 803–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbrouck, J. (1991). Measuring the information content of stock trades. Journal of Finance, 46(1), 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbrouck, J., & Seppi, D. J. (2001). Common factors in prices, order flows, and liquidity. Journal of Financial Economics, 59(3), 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillairet, C. (2004). Equilibres sur un marché financier avec asymétrie d’information et discontinuité des prix [Ph.D. thesis, Université Paul Sabatier-Toulouse III]. [Google Scholar]

- Horst, U., & Naujokat, F. (2011). On derivatives with illiquid underlying and market manipulation. Quantitative Finance, 11(7), 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. D., & Stoll, H. R. (1997). The components of the bid-ask spread: A general approach. Review of Financial Studies, 10(4), 995–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberman, G., & Stanzl, W. (2004). Price manipulation and quasi-arbitrage. Econometrica, 72(4), 1247–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrow, R., Fung, S., & Tsai, S.-C. (2018). An empirical investigation of large trader market manipulation in derivatives markets. Review of Derivatives Research, 21(3), 331–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrow, R. A. (1992). Market manipulation, bubbles, corners, and short squeezes. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 27(3), 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrow, R. A. (1994). Derivative security markets, market manipulation, and option pricing theory. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 29(2), 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M., & Sircar, K. R. (2002). Partial hedging in a stochastic volatility environment. Mathematical Finance, 12(4), 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klock, F. (2014). Price manipulation in a market with interacting investor and venue choice. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics, 5(1), 607–649. [Google Scholar]

- Klöck, F. (2012). Regularity of market impact models with stochastic price (Working paper, May 14, 2012). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2057610 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kraft, H., & Kühn, C. (2011). Large traders and illiquid options: Hedging vs. manipulation. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 35(11), 1898–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, H. E. (1985). Option pricing and replication with transaction costs. Journal of Finance, 40(5), 1283–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. (2017). The new market manipulation. Emory Law Journal, 66(6), 1253–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., & Yong, J. (2005). Option pricing with an illiquid underlying asset market. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 29(12), 2125–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeper, G. (2018). Option pricing with linear market impact and nonlinear black–scholes equations. Annals of Applied Probability, 28(5), 2664–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G., Siu, C. C., Zhu, S.-P., & Elliott, R. J. (2020). Optimal portfolio execution problem with stochastic price impact. Automatica, 112, 108739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, A., Richardson, M., & Roomans, M. (1997). Why security prices change. Review of Financial Studies, 10(4), 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S. X., Pearson, N. D., & Poteshman, A. M. (2005). Stock price clustering on option expiration dates. Journal of Financial Economics, 78(1), 49–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, A. F. (2022). Hedging of American options in illiquid markets with price impacts. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance, 25(01), 2250001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L. C. G., & Shi, Z. (1995). The value of an Asian option. Journal of Applied Probability, 32(4), 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E. (2020). Market impact in systematic trading and option pricing [Ph.D. thesis, Université Paris-Saclay]. [Google Scholar]

- Tankov, P., & Voltchkova, E. (2009). Jump-diffusion models: A practitioner’s guide. Banque et Marchés, 99(1), 24. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, B., Lemperiere, Y., Deremble, C., de Lataillade, J., Kockelkoren, J., & Bouchaud, J.-P. (2011). Anomalous price impact and the critical nature of liquidity in financial markets. Physical Review X, 1(2), 021006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VIX & CBOE. (2025). CBOE volatility index (VIX) historical data. Available online: https://www.cboe.com/tradable_products/vix/vix_historical_data (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Zarinelli, E., Treccani, M., Farmer, J. D., & Lillo, F. (2015). Beyond the square root: Evidence for logarithmic dependence of market impact on size and participation rate. Market Microstructure and Liquidity, 1(02), 1550004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The spot price is in the money but still far from the knock-out (KO) strike. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 1.

The spot price is in the money but still far from the knock-out (KO) strike. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 2.

As the spot moves further up, the delta increases. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 2.

As the spot moves further up, the delta increases. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 3.

Large hedging activity drives the spot into the KO barrier. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 3.

Large hedging activity drives the spot into the KO barrier. The solid curve shows the price of the KO barrier option as a function of the spot price, while the dashed lines indicate the option strikes and the payoff discontinuity at the KO barrier. The red dot represents the current spot price (x-axis) and the corresponding barrier option price (y-axis).

Figure 4.

The terminal cost function for a hedged option. shall be read as a multiple of the notional. Colors encode the magnitude of the terminal cost function on the surface, with a continuous monotonic mapping from lower to higher values.

Figure 4.

The terminal cost function for a hedged option. shall be read as a multiple of the notional. Colors encode the magnitude of the terminal cost function on the surface, with a continuous monotonic mapping from lower to higher values.

Figure 5.

The cost function at time 0 for a hedged call option. Data source: Matlab simulation. Colors encode the magnitude of the cost function on the surface, with a continuous monotonic mapping from lower to higher values.

Figure 5.

The cost function at time 0 for a hedged call option. Data source: Matlab simulation. Colors encode the magnitude of the cost function on the surface, with a continuous monotonic mapping from lower to higher values.

Figure 6.

The optimal shares strategy function at time 0 for a call option. Data source: Matlab simulation. Colors encode the magnitude of the cost function on the surface, with a continuous monotonic mapping from lower to higher values.

Figure 6.