An Evaluation of the Impact of Barcode Patient and Medication Scanning on Nursing Workflow at a UK Teaching Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Duration of drug administration rounds;

- Timeliness of medication dose administration;

- Active identification of patients by nurses;

- Active verification of medication by nurses (BCMA only);

- Walking patterns of nurses on the ward.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design and Data Collection

3. Results

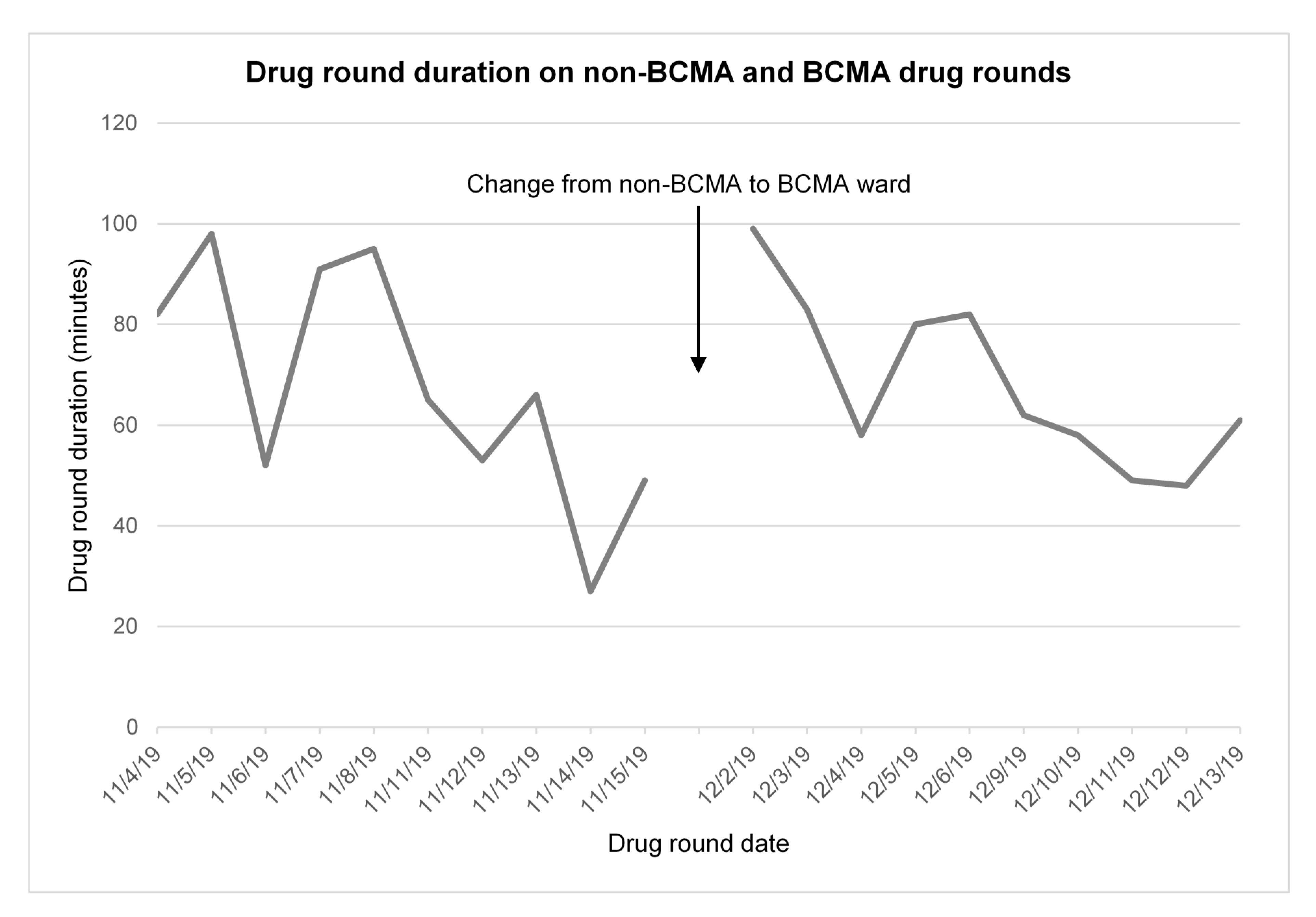

3.1. Drug Administration Round Duration

3.2. Timeliness of Medication Administration

3.3. Active Positive Patient Identification

3.4. Active Positive Medication Verification

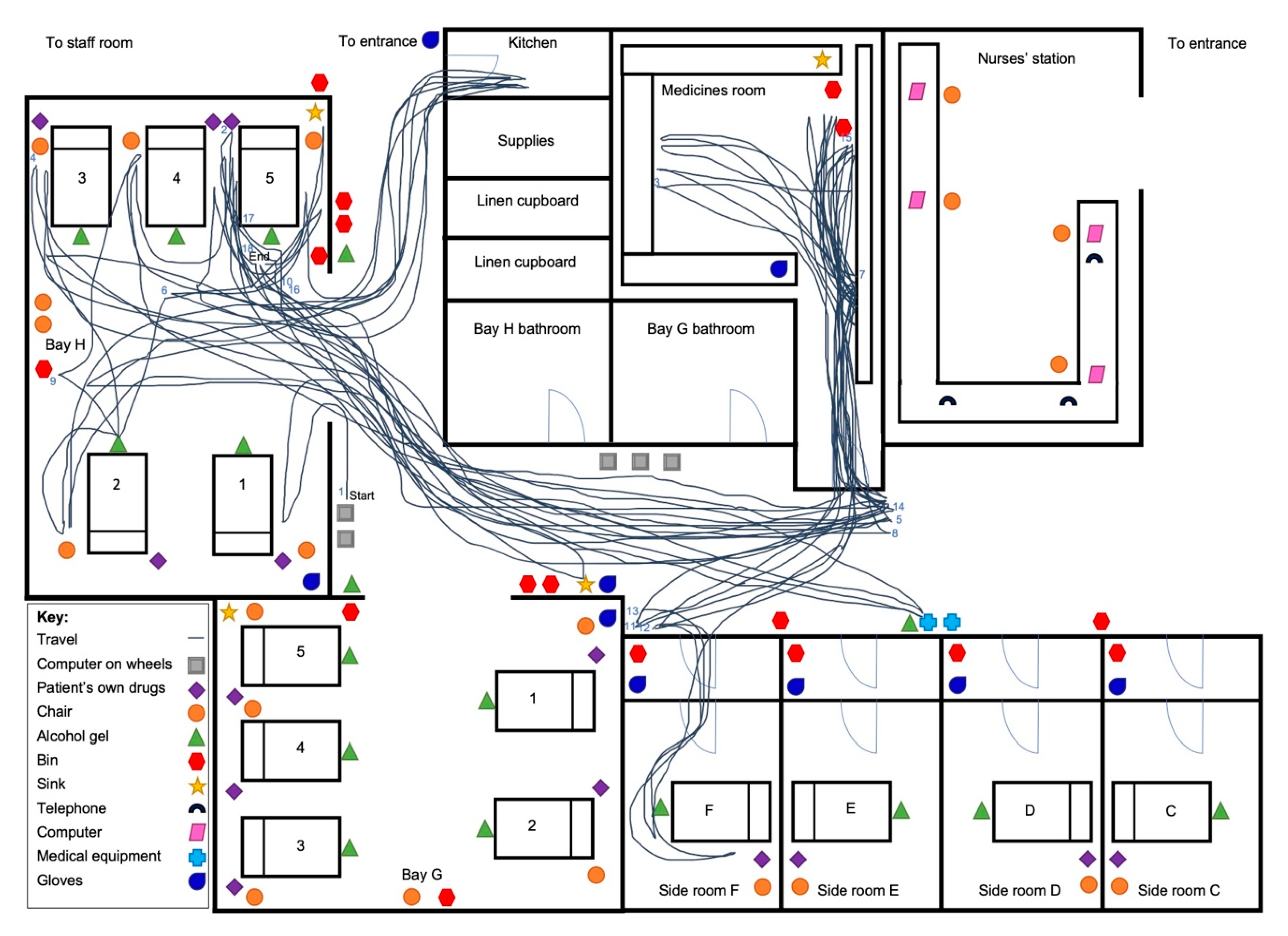

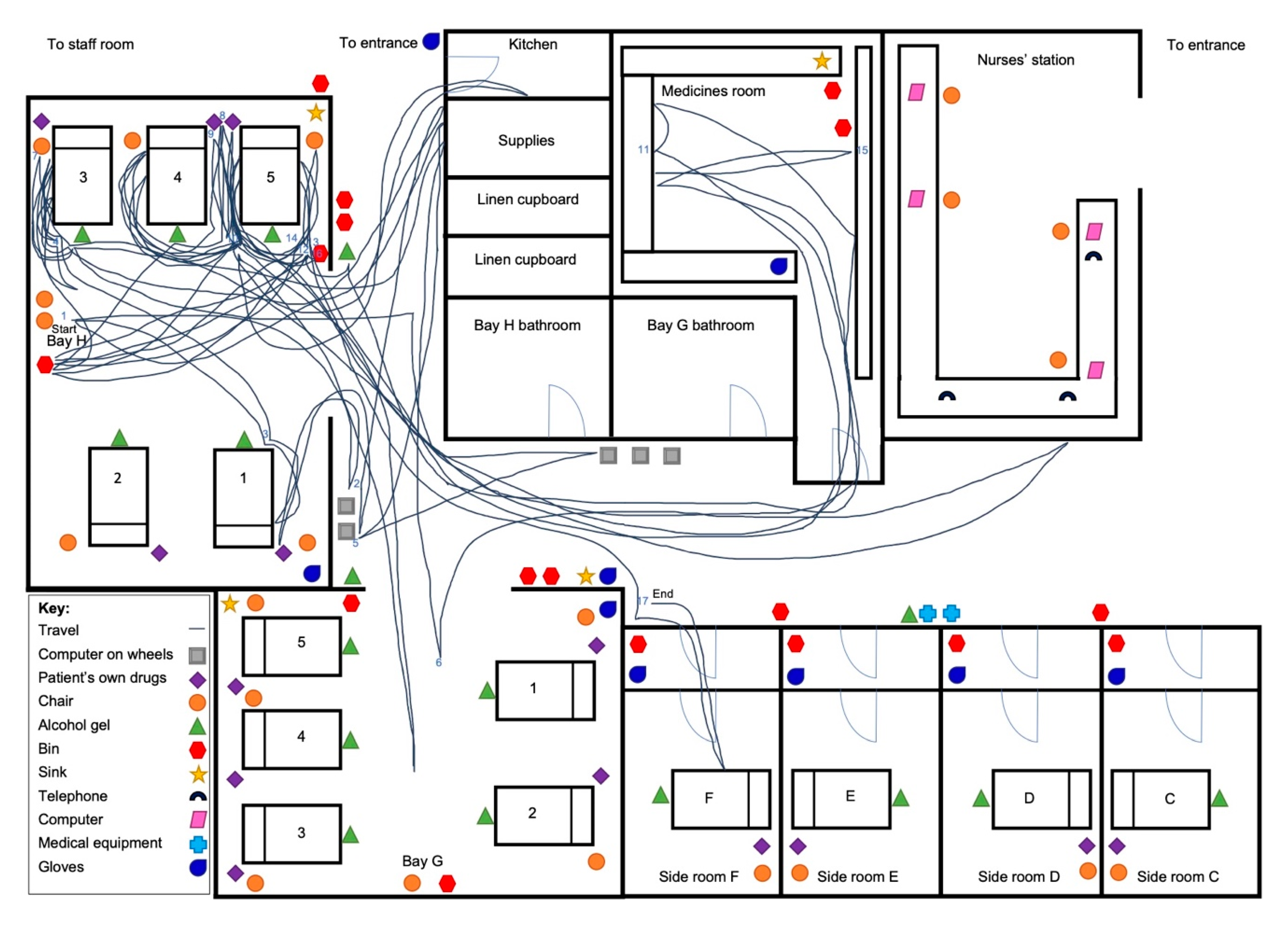

3.5. Observation of Nurse Walking Pattern around the Ward and General Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Comparison to Previous Research

4.3. Interpretations and Implications for Practice

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of Research

4.5. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhatti, S. Closed Loop Medicines Administration Toolkit Implementation Lessons Shared; Global Digital Exemplar Learning Network; 2019. Available online: https://future.nhs.uk/connect.ti/MedsOPDigitalLN/view?objectId=15208880 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Macias, M.; Bernabeu-Andreu, F.A.; Arribas, I.; Navarro, F.; Baldominos, G. Impact of a Barcode Medication Administration System on Patient Safety. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, E1–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, E.G.; Keohane, C.A.; Yoon, C.S.; Ditmore, M.; Bane, A.; Levtzion-Korach, O.; Moniz, T.; Rothschild, J.M.; Kachalia, A.B.; Hayes, J.; et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truitt, E.; Thompson, R.; Blazey-Martin, D.; NiSai, D.; Salem, D. Effect of the Implementation of Barcode Technology and an Electronic Medication Administration Record on Adverse Drug Events. Hosp Pharm. 2016, 51, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonkowski, J.; Carnes, C.; Melucci, J.; Mirtallo, J.; Prier, B.; Reichert, E.; Moffatt-Bruce, S.; Weber, R. Effect of barcode-assisted medication administration on emergency department medication errors. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013, 20, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, B.D.; O’Grady, K.; Donyai, P.; Jacklin, A.; Barber, N. The impact of a closed-loop electronic prescribing and administration system on prescribing errors, administration errors and staff time: A before-and-after study. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2007, 16, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.; Slebodnik, M.; Sands, L. Bar code technology and medication administration error. J. Patient Saf. 2010, 6, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppel, R.; Wetterneck, T.; Telles, J.L.; Karsh, B.T. Workarounds to barcode medication administration systems: Their occurrences, causes, and threats to patient safety. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 2008, 15, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, R.J.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J.; Faye, H.; Scanlon, M.C.; Karsh, B.T. Automation and adaptation: Nurses’ problem-solving behavior following the implementation of bar coded medication administration technology. Cogn. Technol. Work 2013, 15, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lee, T.T. Impact of bar-code medication administration on nursing activity patterns and usage experience in Taiwan. Comput. Inf. Nurs. 2011, 29, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, E.G.; Keohane, C.A.; Bane, A.; Featherstone, E.; Hays, B.S.; Dervan, A.; Woolf, S.; Hayes, J.; Newmark, L.P.; Gandhi, T.K. Impact of barcode medication administration technology on how nurses spend their time providing patient care. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2008, 38, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwibedi, N.; Sansgiry, S.S.; Frost, C.P.; Dasgupta, A.; Jacob, S.M.; Tipton, J.A.; Shippy, A.A. Effect of bar-code-assisted medication administration on nurses’ activities in an intensive care unit: A time–motion study. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2011, 68, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topps, C.; Lopez, L.; Messmer, P.R.; Franco, M. Perceptions of pediatric nurses toward bar-code point-of-care medication administration. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2005, 29, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaranayake, N.R.; Cheung, S.T.; Cheng, K.; Lai, K.; Chui, W.C.; Cheung, B.M. Implementing a bar-code assisted medication administration system: Effects on the dispensing process and user perceptions. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2014, 83, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, A.C.; Bane, A.; Fotakis, S.; Duffy, M.E.; Sevigny, A.; Poon, E.G.; Gandhi, T.K. Nurses’ satisfaction with medication administration point-of-care technology. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2007, 37, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carayon, P.; Wetterneck, T.B.; Hundt, A.S.; Ozkaynak, M.; DeSilvey, J.; Ludwig, B.; Ram, P.; Rough, S.S. Evaluation of nurse interaction with bar code medication administration technology in the work environment. J. Patient Saf. 2007, 3, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerner Corporation. Medication management 2020. Available online: https://www.cerner.com/gb/en/solutions/medication-management (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- McLeod, M.; Barber, N.; Franklin, B.D. Facilitators and Barriers to Safe Medication Administration to Hospital Inpatients: A Mixed Methods Study of Nurses’ Medication Administration Processes and Systems (the MAPS Study). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wilder, A.; Bell, H.; Franklin, B.D. The effect of electronic prescribing and medication administration on nurses’ workflow and activities: An uncontrolled before and after study. Saf. Health 2016, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.L. Measuring and accounting for the Hawthorne effect during a direct overt observational study of intensive care unit nurses. Am. J. Infect. Control 2017, 45, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome Measure | Method |

|---|---|

| Drug administration round duration | The time from opening the electronic record on the COW for the first patient to the time when the last medication dose was recorded as being administered on the COW for the last patient was recorded for each drug round. The timed drug round therefore encompassed any activities the nurse performed on the round and any interruptions. The number of patients taking one or more medications, the number of doses that were due and the number of doses that were administered were also recorded to facilitate data analysis. |

| Timeliness of medication administration | The time for which each dose of medication was scheduled and the time when it was actually administered was recorded. This included only doses of medication administered that could directly be observed as having been given. Medications that were administered ‘when required’ were excluded since a time difference could not be calculated for these. The difference between the administered time and the scheduled dose time was then determined for each dose on both wards. |

| Active positive patient identification activity | On the non-BCMA ward, an active positive identification was defined in line with hospital policy as the nurse confirming at least two patient identifiers (such as name and date of birth) either by manually checking the patient’s wristband or verbally asking the patient prior to medication administration. On the BCMA ward, an active positive identification was defined as the nurse scanning the barcode on the patient’s wristband or confirming two patient identifiers as before. The method used in each case was also recorded. |

| Active positive medication dose verification activity | The active verification of doses was only measured on the BCMA ward as it was not possible to determine whether a nurse had verified the medication as part of their thought process without BCMA. A positive verification involved the nurse scanning the barcode on the medication; we recorded whether this was done or not for each dose, together with any reasons why the medication doses were not scanned, and any potential workarounds observed. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barakat, S.; Franklin, B.D. An Evaluation of the Impact of Barcode Patient and Medication Scanning on Nursing Workflow at a UK Teaching Hospital. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030148

Barakat S, Franklin BD. An Evaluation of the Impact of Barcode Patient and Medication Scanning on Nursing Workflow at a UK Teaching Hospital. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(3):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030148

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarakat, Sara, and Bryony Dean Franklin. 2020. "An Evaluation of the Impact of Barcode Patient and Medication Scanning on Nursing Workflow at a UK Teaching Hospital" Pharmacy 8, no. 3: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030148

APA StyleBarakat, S., & Franklin, B. D. (2020). An Evaluation of the Impact of Barcode Patient and Medication Scanning on Nursing Workflow at a UK Teaching Hospital. Pharmacy, 8(3), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030148