Pharmacist–Physician Collaboration to Improve the Accuracy of Medication Information in Electronic Medical Discharge Summaries: Effectiveness and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Study Design

2.2. Electronic Information and Prescribing Systems Used in the Study Hospital

2.3. Preparation of EDSs Prior to the Intervention

- A hospital physician (usually an intern or junior medical officer) prepared a discharge prescription, then printed and signed the paper copy. Hospital policy was that all medications intended to be taken after discharge were to be included on the prescription, regardless of whether or not they needed to be dispensed, to ensure an accurate electronic record;

- A hospital pharmacist reviewed the paper discharge prescription and performed medication reconciliation by comparing the prescription with the patient’s inpatient medication administration record and pre-admission medication history (which had been recorded and verified by a pharmacist upon admission to hospital) to identify unintended discharge prescription discrepancies (e.g., omitted medications, unnecessary medications, dose errors, dose-form errors);

- The pharmacist discussed discrepancies with the prescriber, and amendments to the discharge prescription were agreed:

- For amendments that did not require a new paper prescription (e.g., cessation of medication, addition of medication that did not need to be dispensed because the patient had a supply at home, change of dosage/directions), the pharmacist and/or doctor annotated and signed the amendment on the paper prescription. The hospital doctor was expected to also make the amendment in the e-prescription record, but there was no mechanism to ensure or check that this was done;

- For other amendments, the pharmacist requested a new prescription be printed and signed by the hospital physician;

- Using the pharmacist-verified paper prescription, discharge medications were dispensed by the hospital’s pharmacy department. Scanned copies of the processed paper prescription were stored electronically;

- The hospital physician, again usually a junior, prepared the EDS:

- The electronic record of the discharge prescription was imported into the EDS by clicking on a link within the EDS;

- Information about medication changes and reasons for changes were manually entered into the EDS.

- The EDS was signed off by the hospital physician and automatically transmitted electronically to the patient’s primary care physician.

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Sample Selection

- were discharged to another hospital;

- died in hospital;

- did not take any medications prior to admission and were not prescribed medications on discharge;

- did not have a completed EDS in the medical record;

- had missing records that were required for the audit (e.g., pharmacist-verified “Medication History on Admission” form or pharmacist-reviewed and reconciled paper discharge prescription).

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Clinical Significance of Medication Changes and EDS Discrepancies

2.8. Time Required and Barriers to Delivering the Intervention

2.9. Primary Outcome Measures

- Proportion of EDSs with one or more clinically significant medication list discrepancies;

- Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were stated in the EDS;

- Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were both stated and explained in the EDS.

2.10. Secondary Outcome Measures

- Number of EDS medication list discrepancies per patient;

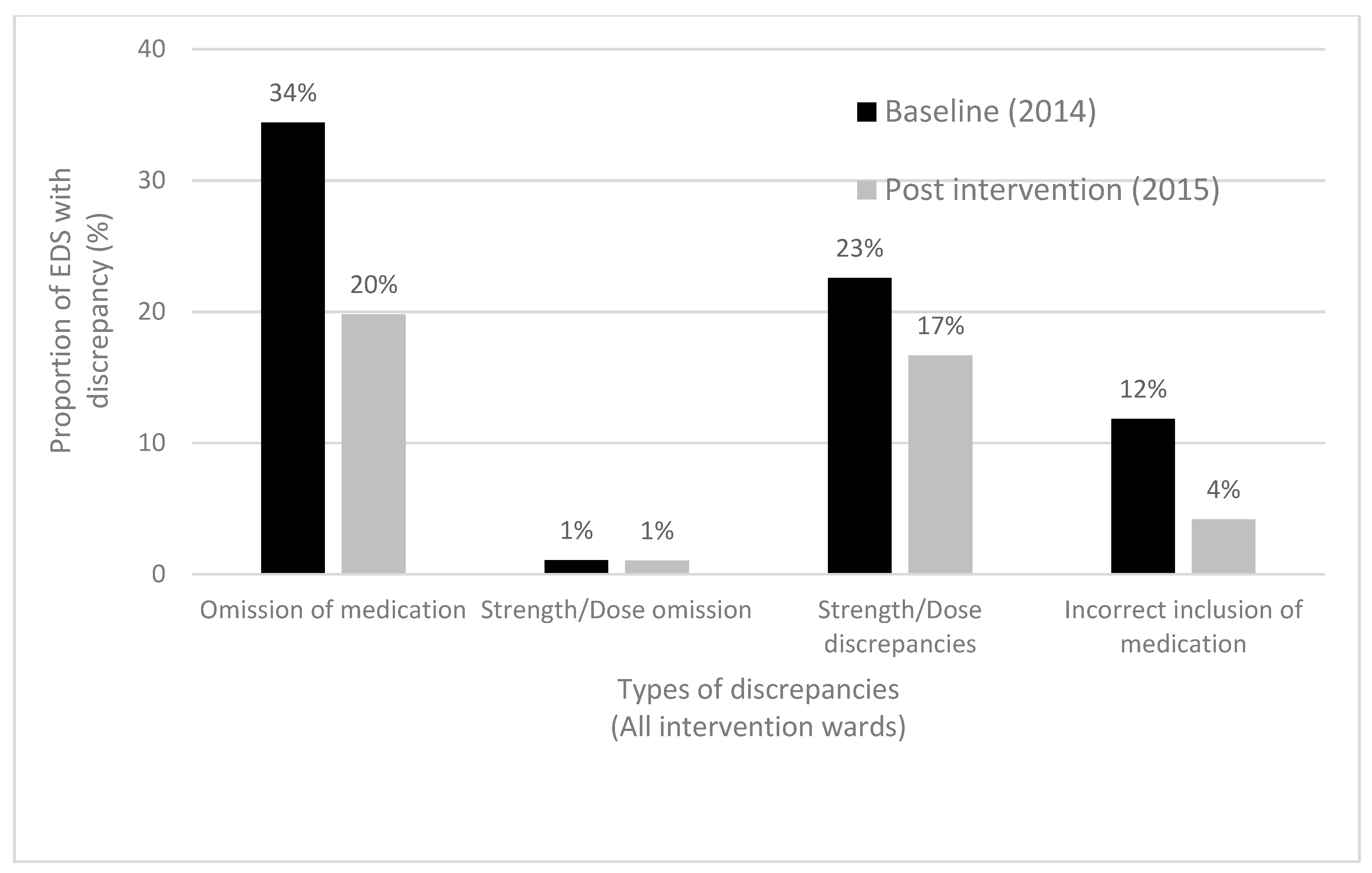

- Types of medication list discrepancies;

- Proportion of EDSs with evidence of pharmacist verification;

- Time required by pharmacists to deliver the intervention.

2.11. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. All Pilot Intervention Wards: Baseline (2014), Post-Intervention (2015)

3.1.1. Study Sample

3.1.2. Accuracy of Medication Lists in EDSs

3.1.3. Communication of Medication Changes in the EDS

3.2. Aged Care Wards: Baseline (2014), Post-Intervention (2015), Post-Intervention (2017)

3.2.1. Study Sample

3.2.2. Accuracy of Medication Lists in EDSs

3.2.3. Communication of Medication Changes in the EDS

3.3. Pharmacist Verification of EDS Medication Lists

3.4. Time to Deliver the Intervention

3.5. Barriers to Delivery

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwarz, C.M.; Hoffmann, M.; Schwarz, P.; Kamolz, L.; Brunner, G.; Sendlhofer, G. A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis on the risks of medical discharge letters for patients’ safety. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group Inc. National Quality Use of Medicines Indicators for Australian Hospitals; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2014. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/national-indicators-quality-use-medicines-qum-australian-hospitals (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Kripalani, S.; LeFevre, F.; Phillips, C.O.; Williams, M.V.; Basaviah, P.; Baker, D.W. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007, 297, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roughead, E.E.; Semple, S.J.; Rosenfeld, E. The extent of medication errors and adverse drug reactions throughout the patient journey in acute care in Australia. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2016, 14, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakib, S.; Philpott, H.; Clark, R. What we have here is a failure to communicate! Improving communication between tertiary to primary care for chronic heart failure patients. Intern. Med. J. 2009, 39, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cornu, P.; Steurbaut, S.; Leysen, T.; De Baere, E.; Ligneel, C.; Mets, T.; Dupont, A.G. Discrepancies in medication information for the primary care physician and the geriatric patient at discharge. Ann. Pharmacother. 2012, 46, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleli, E.; Naccarella, L.; Pirotta, M. Communication at the interface between hospitals and primary care—A general practice audit of hospital discharge summaries. Aust. Fam. Physician 2013, 42, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammad, E.A.; Wright, D.J.; Walton, C.; Nunney, I.; Bhattacharya, D. Adherence to UK national guidance for discharge information: An audit in primary care. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Mulo, B.; Skinner, M. Transition from hospital to primary care: An audit of discharge summary—Medication changes and follow-up expectations. Intern. Med. J. 2014, 44, 1124–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Elliott, R.A.; Richardson, B.; Tanner, F.E.; Dorevitch, M.I. An audit of the accuracy of medication information in electronic medical discharge summaries linked to an electronic prescribing system. Health Inf. Manag. J. 2018, 47, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowasser, D.A.; Collins, D.M.; Stowasser, M. A randomised controlled trial of medication liaison services—Patient outcomes. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2002, 32, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.A. Falling through the cracks: Challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.J.; Murff, H.J.; Peterson, J.F.; Gandhi, T.K.; Bates, D.W. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherington, E.M.; Pirzada, O.M.; Avery, A.J. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: Observational study. Qual. Saf. Health Care. 2008, 17, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivji, F.S.; Ramoutar, D.N.; Bailey, C.; Hunter, J.B. Improving communication with primary care to ensure patient safety post-hospital discharge. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2015, 76, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, A.V.; Patel, B.K.; Roberts, M.S.; Williams, D.B.; Crofton, J.H.; Morris, N.M.; Wallace, J.; Gilbert, A.L. An audit of medicines information quality in electronically generated discharge summaries—Evidence to meet the Australian National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2017, 47, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P.R.; Weidmann, A.E.; Stewart, D. Hospital discharge information communication and prescribing errors: A narrative literature overview. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2016, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, S.; Adenew, A.B.; Arundel, C.; Maron, D.D.; Kerns, J.C. Medication errors despite using Electronic Health Records: The value of a clinical pharmacist service in reducing discharge-related medication errors. Q. Manag. Health Care 2016, 25, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Elliott, R.A.; Taylor, S.E.; Garrett, K. Development and evaluation of an hospital pharmacy generated interim residential care medication administration chart. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2012, 42, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, M.; Hill, A.; Wynn, A.; Kelly, L. Accuracy of pharmacist electronic discharge medicines review information transmitted to primary care at discharge. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, A.B.; McLachlan, A.J.; Brien, J.E. Pharmacy-led medication reconciliation programmes at hospital transitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, A.; Midlov, P.; Hoglund, P.; Larsson, L.; Bondesson, A.; Eriksson, T. Improved quality in the hospital discharge summary reduces medication errors—LIMM: Landskrona Integrated Medicines Management. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, E.Y.; Roman, C.P.; Mitra, B.; Yip, G.S.; Gibbs, H.; Newnham, H.H.; Smit, V.; Galbraith, K.; Dooley, M.J. Reducing medication errors in hospital discharge summaries: A randomised controlled trial. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 206, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.E.; Rofe, O.; Vienet, M.; Elliott, R.A. Improving communication of medication changes using a pharmacist-prepared discharge medication management summary. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duedahl, T.H.; Hansen, W.B.; Kjeldsen, L.J.; Graabæk, T. Pharmacist-led interventions improve quality of medicine-related healthcare service at hospital discharge. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2018, 25, e40–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderton, M.; Callen, J. Are general practitioners satisfied with electronic discharge summaries? Health Inf. Manag. 2007, 36, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, B.H.; Djønne, B.S.; Skjold, F.; Mellingen, E.M.; Aag, T.I. Quality of medication information in discharge summaries from hospitals: An audit of electronic patient records. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeys, C.; Kalejaiye, B.; Skinner, M.; Eimen, M.; Neufer, J.; Sidbury, G.; Buster, N.; Vincent, J. Pharmacist-managed inpatient discharge medication reconciliation: A combined onsite and telepharmacy model. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 2159–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebaaly, J.; Parsons, L.B.; Pilch, N.A.; Bullington, W.; Hayes, G.L.; Easterling, H. Clinical and financial impact of pharmacist involvement in discharge medication reconciliation at an academic medical center: A prospective pilot study. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 50, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craynon, R.; Hager, D.R.; Reed, M.; Pawola, J.; Rough, S.S. Prospective daily review of discharge medications by pharmacists: Effects on measures of safety and efficiency. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2018, 75, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafzadeh, M.; Schnipper, J.L.; Shrank, W.H.; Kymes, S.; Brennan, T.A.; Choudhry, N.K. Economic value of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation for reducing medication errors after hospital discharge. Am. J. Manag. Care 2016, 22, 654–661. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.A.; Perera, D.; Mouchaileh, N.; Antoni, R.; Woodward, M.; Tran, T.; Garrett, K. Impact of an expanded ward pharmacy technician role on service-delivery and workforce outcomes in a subacute aged care service. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2014, 44, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.M. Interdisciplinary collaboration in the provision of a pharmacist-led discharge medication reconciliation service at an Irish teaching hospital. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 37, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marvin, V.; Kuo, S.; Poots, A.J.; Woodcock, T.; Vaughan, L.; Bell, D. Applying quality improvement methods to address gaps in medicines reconciliation at transfers of care from an acute UK hospital. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, V.; deClifford, J.M.; Lam, S.; Subramaniam, A. Implementation and evaluation of a collaborative clinical pharmacist’s medications reconciliation and charting service for admitted medical inpatients in a metropolitan hospital. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2016, 41, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.H.; May, J.A. The challenge of discharge: Combining medication reconciliation and discharge planning. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 206, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) All Pilot Intervention Wards | (b) Aged Care Wards only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (2014) | Post-Intervention (2015) | Baseline (2014) | Post-Intervention (2015) | Post-Intervention (2017) | |

| No completed electronic discharge summaries (EDSs) in Cerner | 8 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Scanned copy of pharmacist-reviewed and reconciled discharge prescription missing, incomplete ^ or illegible * | 14 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Pharmacist-verified ‘Medication History on Admission’ form absent from medical record | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Patient discharged to another hospital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Total | 22 | 24 | 5 | 7 | 20 |

| Demographics | Baseline (2014) (n = 93) | Post-Intervention (2015) (n = 96) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 79 (65–85) | 81 (70–86) |

| Gender | ||

| Male, number (%) Female, number (%) | 40 (43) 53 (57) | 47 (49) 49 (51) |

| Length of admission (days), median (IQR) | 6 (4–21) | 6 (3–17) |

| Number of regular medications on discharge, median (IQR) | 9 (5–12) | 8 (5–11) |

| Number of changes to pre-admission medication regimen made in hospital, median (IQR) | 4 (3–7) | 4 (2–6) |

| Number of clinically significant changes to pre-admission medication regimen made in hospital, median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) |

| Baseline (2014) (n = 93) | Post-Intervention (2015) (n = 96) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of EDS medication list discrepancies | 129 | 53 | N/A |

| Proportion of EDSs with one or more medication list discrepancies, n (%) | 62/93 (67) | 36/96 (38) | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) number of EDS medication list discrepancies per patient | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| Total number of clinically significant medication list discrepancies | 63 | 15 | N/A |

| Proportion of EDSs with one or more clinically significant medication list discrepancies, n (%) | 40/93 (43) | 14/92 (15) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were stated in the EDS, n (%) | 222/417 (53) | 296/366 (81) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were stated AND explained in the EDS, n (%) | 206/417 (49) | 245/366 (67) | <0.001 |

| Proportion of EDSs with evidence of pharmacist verification, n (%) | N/A | 45/96 (47) | N/A |

| Baseline (2014) (n = 41) | Post-Intervention (2015) (n = 42) | Post-Intervention (2017) (n = 76) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 84 (80–90) | 82 (76–84) | 82 (72–87) |

| Gender | |||

| Male, number (%) Female, number (%) | 17 (41) 24 (59) | 24 (57) 18 (43) | 31 (41) 45 (59) |

| Length of admission (days), median (IQR) | 20 (7–29) | 17 (7–36) | 33 (19–51) |

| Number of regular discharge medications, median (IQR) | 9 (7–12) | 9 (6–11) | 9 (5–13) |

| Number of medication changes, median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3.25–6) | 7 (6–11.25) |

| Number of clinically significant medication changes, median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–6) | 7 (5–11) |

| Baseline (2014) (n = 41) | Post-Intervention (2015) (n = 42) | Post-Intervention (2017) (n = 76) | p-Value (All Groups) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of EDS medication list discrepancies | 43 | 15 | 58 | N/A |

| Proportion of EDSs with one or more medication list discrepancies, n (%) | 26/41 (63) | 11/42 (26) * | 27/76 (36) * | 0.001 |

| Median (IQR) number of EDS medication list discrepancies per patient | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) * | 0 (0–1) * | <0.001 |

| Total number of clinically significant medication list discrepancies | 23 | 6 | 27 | N/A |

| Proportion of EDSs with one or more clinically significant medication list discrepancies, n (%) | 18/41 (44) | 5/42 (12) * | 18/76 (24) * | 0.003 |

| Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were stated in the EDS, n (%) | 109/219 (50) | 185/212 (87) * | 464/612 (76) *,# | <0.001 |

| Proportion of clinically significant medication changes that were stated AND explained in the EDS, n (%) | 94/219 (43) | 141/212 (67) * | 403/612 (66) * | <0.001 |

| Proportion of EDSs with evidence of pharmacist verification, n (%) | N/A | 27/42 (64) | 52/76 (68) | 0.65 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elliott, R.A.; Tan, Y.; Chan, V.; Richardson, B.; Tanner, F.; Dorevitch, M.I. Pharmacist–Physician Collaboration to Improve the Accuracy of Medication Information in Electronic Medical Discharge Summaries: Effectiveness and Sustainability. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010002

Elliott RA, Tan Y, Chan V, Richardson B, Tanner F, Dorevitch MI. Pharmacist–Physician Collaboration to Improve the Accuracy of Medication Information in Electronic Medical Discharge Summaries: Effectiveness and Sustainability. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleElliott, Rohan A., Yixin Tan, Vincent Chan, Belinda Richardson, Francine Tanner, and Michael I. Dorevitch. 2020. "Pharmacist–Physician Collaboration to Improve the Accuracy of Medication Information in Electronic Medical Discharge Summaries: Effectiveness and Sustainability" Pharmacy 8, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010002

APA StyleElliott, R. A., Tan, Y., Chan, V., Richardson, B., Tanner, F., & Dorevitch, M. I. (2020). Pharmacist–Physician Collaboration to Improve the Accuracy of Medication Information in Electronic Medical Discharge Summaries: Effectiveness and Sustainability. Pharmacy, 8(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010002