Balancing Assessment with “In-Service Practical Training”: A Case Report on Collaborative Curriculum Design for Delivery in the Practice Setting

Abstract

1. Background and Introduction

- (i)

- To describe the structures necessary to operationalize these new requirements.

- (ii)

- To explain the alignment of student contact hours in the online modules with placement hours.

- (iii)

- To define Preceptors and their scope.

- (iv)

- To outline the criteria for curriculum design.

- (v)

- To define and explain the two stages of the work programme, i.e., Stage 1: Establishment of Working Group (WG) and Stage 2: Curriculum Design.

- (i)

- To designate the outcomes achieved and their linkage to CCF, learning outcomes, assessment, teaching, and learning.

- (ii)

- To describe the outputs achieved, and to discuss in the context of the literature.

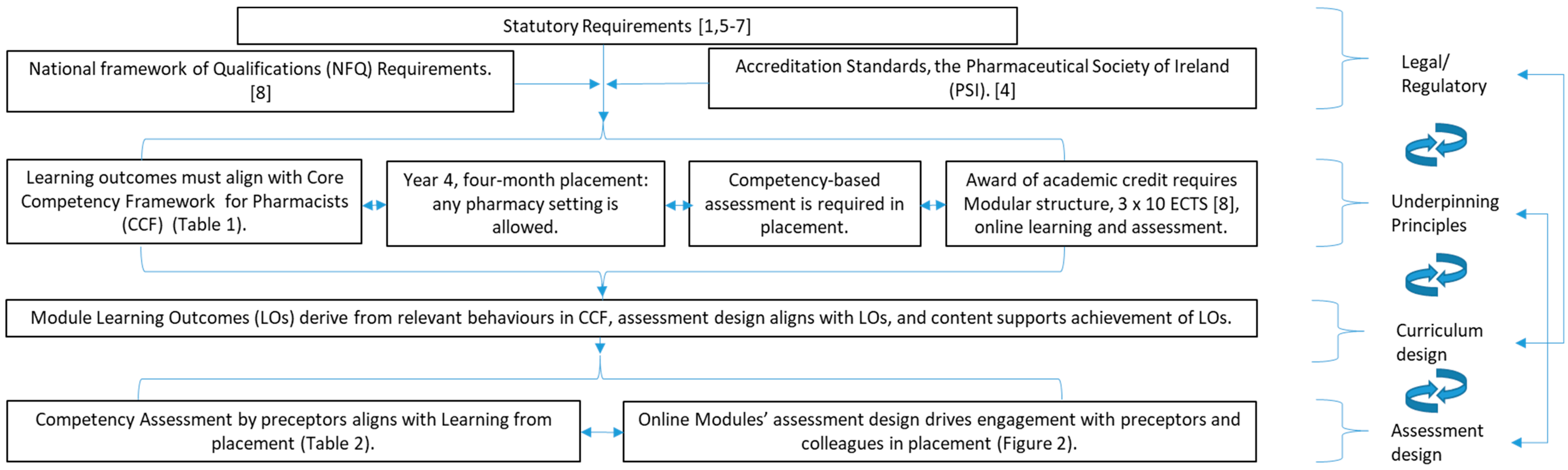

2. Planning Phase

2.1. Structures

2.2. Alignment of Student Contact Hours

2.3. Preceptors and Their Scope

2.4. Criteria for Curriculum Design

- Materials should be co-delivered to students from all three HEIs while on Year 4 placement, from September to December of that academic year;

- there should be no requirement for students to attend the HEI at any stage during the placement;

- activities that require access to patients or patients’ records should be excluded;

- learning outcomes to be derived from the same CCF behaviours as used for the placement assessment;

- alignment with 30 ECTS academic credit for Year 4 of the Degree award, and with student workload of a maximum 20 h per week for a total of 15 weeks is a requirement;

- there should be no additional preceptor workload when designing activities/assessment; and

- standards and/or regulations for curriculum design, and for progression and award of Degrees, at all three HEIs were to be accommodated.

2.5. Stages of Work Programme

3. Implementation Phase

3.1. Module Links to CCF

- The WG reviewed behaviours listed in the three Domains in the CCF and recommended that 51 behaviours be included (Appendix A, Table A1).

- Each module was linked to a number of CCF competencies and behaviours relevant to the range of placement types possible in Year 4 (Appendix A, Table A1).

- These behaviours guided the development of LOs for each module.

3.2. Module Learning Outcomes (LOs)

- Module learning outcomes were devised based on covering the cognitive (knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis), affective, and psychomotor domains relevant to a student in Ireland. [42]

- Eight LOs were agreed for each module, of which three LOs were common across each module—i.e., (i) Participate in accordance with the behaviours in domain [x] of the CCF; (ii) Integrate knowledge and skills to ensure safe and effective practice; and (iii) Demonstrate engagement in reflective practice and continuing professional development.

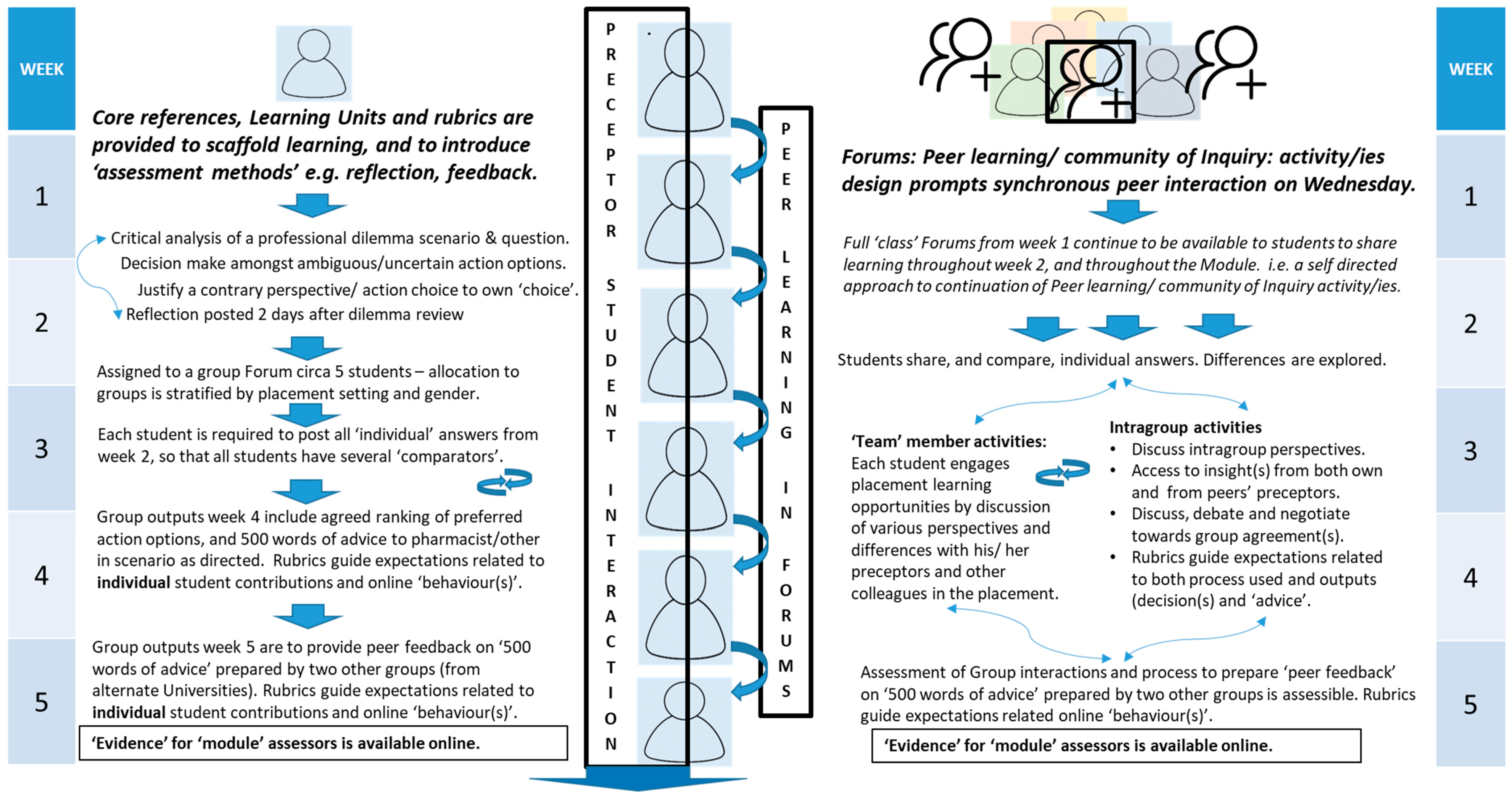

3.3. Approaches to Assessment

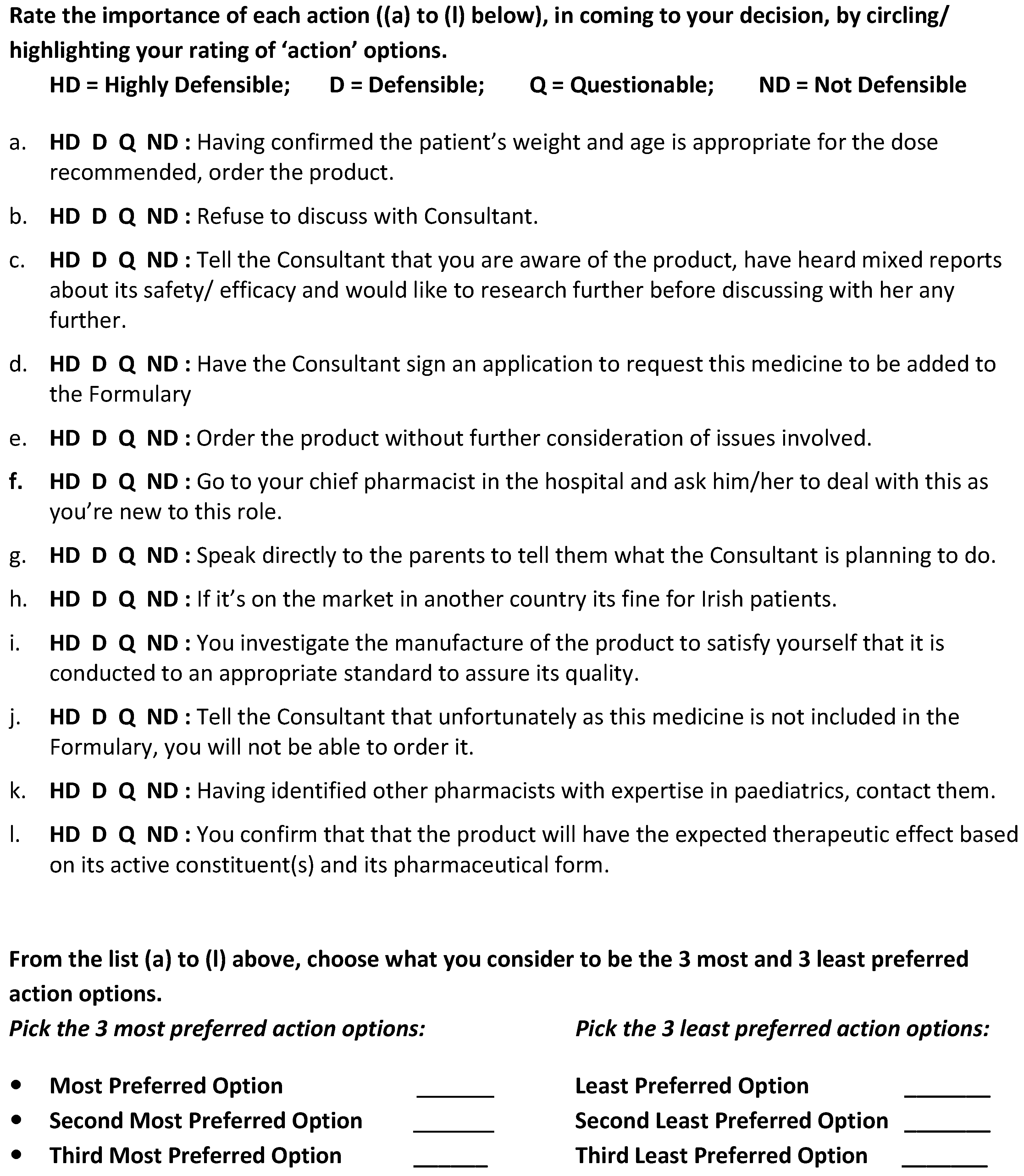

- Each module included one case-based assessment, to assist in achieving the LOs, that requires (i) Individual and group work, and (ii) self- and peer assessment (Figure 2).

3.4. Approaches to Teaching and Learning

- Student workload was determined to be ten hours per week on structured learning (directed learning (DL)) activities, and 10 h per week on personal learning (self-directed learning (SDL)) activities.

- 30 h per week were assigned to placement related activity.

- Reference to DL included provision of nine 20 min interactive vodcasts/Learning Units (LUs) and two ‘core references’, that collectively supported achievement of the LOs and completion of assignments in each module.

3.5. Outputs

- Three 10 ECTS Modules, each of which aligned with 200 to 250 h of student effort, [43] were developed.

- Credits aligned with 10ECTS are divided between individual (50%) and group activities (50%). Nine LUs were developed, and weekly synchronous, online activities which include self-directed learning, individual and group activities are aligned with scheduled time online, between 1:00 p.m. and 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday afternoons.

- Case video (Appendix A, Table A3) is used as a vehicle to pose relevant questions and motivate discussion within groups. Two core references, available to students prior to viewing the video, provide background information for the case.

- All student activities/outputs were collated to the group’s online discussion Forum i.e., all ‘evidence’ is available in the one discussion Forum.

- Detailed rubrics, with a total of 10 criteria, provided guidance to students and to assessors. (See Appendix A, Table A4 for individual activities rubric and Appendix A, Table A5 for group activities rubric).

- A student guidance booklet and a module co-ordinator information booklet were developed.

- Weekly announcements, reminding students of activities and related expectations of them during that week, were prepared.

- A weekly schedule, of student learning and assessment, is provided in Appendix A, Table A6.

4. Review Phase

4.1. Challenges

4.2. Learnings

4.3. Recommendations for Future Work

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CCF Behaviours Aligned with Year 4 Online Modules |

|---|

| Professional Practice Module |

| 1.1 Practices ‘patient-centred’ care |

| 1.1.1 Demonstrates a ‘patient-centred’ approach to practice |

| 1.1.2 Ensures patient safety and quality are at the centre of the pharmacy practice |

| 1.2 Practices professionally |

| 1.2.2 Demonstrates awareness of the position of trust in which the profession is held and practises in a manner that upholds that trust |

| 1.2.3 Treats others with sensitivity, empathy, respect and dignity |

| 1.2.4 Takes responsibility for their own actions and for patient care |

| 1.2.7 Recognises their scope of practice and the extent of their current competency and expertise and works accordingly |

| 1.2.8 Maintains a consistently high standard of work |

| 1.3 Practices Legally |

| 1.3.2 Understands and applies the requirements of both Irish and European pharmacy and medicines law |

| 1.3.3 Demonstrates an awareness of other legislation relevant to their practice setting including as appropriate data protection law, health and safety law, employment law, consumer law, equality law and intellectual property rights |

| 1.3.4 Demonstrates an understanding of the requirements of the regulatory framework to authorise a medicinal product including the quality, safety and efficacy requirements |

| 1.4 Practices ethically |

| 1.4.1 Understands their obligations under the principles of the statutory Code of Conduct for Pharmacists and acts accordingly |

| 1.4.2 Makes and justifies decisions in a manner that reflects the statutory Code of Conduct for pharmacists and pharmacy and medicines law |

| 1.4.3 Recognises ethical dilemmas in practice scenarios and reasons through dilemmas in a structured manner |

| 1.5 Engages in appropriate continuing professional development (CPD) |

| 1.5.1 Understands and accepts the importance of life-long learning for pharmacists |

| 1.5.2 Demonstrates the ability to critically reflect on their own practice and skills, to identify learning and development needs |

| 1.5.3 Takes personal responsibility for engaging in CPD and achieving learning and professional development goals |

| 1.5.4 Identifies and undertakes appropriate learning activities and programmes that meet identified learning needs |

| Personal Skills Module |

| 2.1 Leadership skills |

| 2.1.1 Inspires confidence and applies assertiveness skills as appropriate |

| 2.1.2 Leads by example by acting to ensure patient safety and quality within the pharmacy environment |

| 2.1.3 Builds credibility and portrays the profession in a positive light by being professional and well informed |

| 2.2 Decision-making skills |

| 2.2.2 Makes decisions and solves problems in a timely manner |

| 2.2.3 Gathers information from a number of reliable sources and people to enable them to make well-founded decisions |

| 2.2.4 Communicates decisions comprehensively including the rationale behind decisions |

| 2.2.5 Ensures that relevant professional, ethical and patient safety factors are fully considered in decisions into which they have an input |

| 2.2.6 Distinguishes between important and unimportant issues |

| 2.2.7 Demonstrates an attention to detail and accuracy in decision-making |

| 2.2.8 Recognises when it is appropriate to seek advice from experienced colleagues, refer decisions to a higher level of authority or to include other colleagues in the decision |

| 2.3 Team working skills |

| 2.3.1 Recognises the value and structure of the pharmacy team and of a multiprofessional team |

| 2.3.5 Demonstrates a broad understanding of the services delivered by other healthcare professionals and disciplines |

| 2.4 Communication skills |

| 2.4.1 Uses effective verbal, non-verbal, listening and written communication skills to communicate clearly, precisely and appropriately |

| 2.4.3 Uses appropriate language and checks understanding |

| 2.4.4 Demonstrates respect, cultural awareness, sensitivity and empathy when communicating |

| 2.4.5 Demonstrates influencing and negotiation skills to resolve conflicts and problems |

| Organisation and Management Skills Module |

| 6.1 Self-management skills |

| 6.1.1 Demonstrates organisation and efficiency in carrying out their work |

| 6.1.2 Ensures their work time and processes are appropriately planned and managed |

| 6.1.3 Demonstrates the ability to prioritise work appropriately |

| 6.1.4 Takes responsibility as appropriate in the workplace |

| 6.1.5 Demonstrates awareness of the responsibility of their position |

| 6.1.6 Ensures punctuality and reliability |

| 6.1.7 Reflects on and demonstrates learning from critical incidents |

| 6.2 Workplace management skills |

| 6.2.1 Demonstrates an understanding of the principles of organisation and management |

| 6.2.2 Works effectively with the documented procedures and policies within the workplace |

| 6.2.3 Understands their role in the organisational structure and works effectively within the management structure of the organisation |

| 6.2.5 Addresses and manages day to day management issues as required in their position of responsibility |

| 6.3 Human resources management skills |

| 6.3.3 Engages with systems and procedures for performance management |

| 6.3.4 Supports and contributes to staff training and continuing professional development |

| 6.5 Quality assurance |

| 6.5.1 Recognises quality as a core principle of medicines management and healthcare provision |

| 6.5.2 Understands the role of policies and procedures in the organisational structure and in the provision of healthcare |

| 6.5.3 Contributes to the development, implementation, maintenance and training of staff on standard operating procedures, as appropriate to their level of responsibility |

| 6.5.4 Contributes to regular audit activities and reports and acts upon findings |

| Module Title | Professional Practice (Extracts from Module Descriptor) |

|---|---|

| Credit | 10 ECTS |

| Elective/Mandatory | Mandatory |

| Sequence | Year 4 Placement Module 1 |

| Indicative Weekly Schedule | Directed/Structured

|

| Duration | 6 weeks [1 week orientation + 5 weeks of module] |

| Module Coordinators | Assoc. Prof. Cicely Roche (TCD) Dr. Laura Sahm (UCC) Dr. Matthew Lynch (RCSI) |

| Pre-requisites | Completion of year 3 |

| Module Rationale | This module focuses on CCF Domain 1, Professional Practice and helps students develop the concept of what it means to be a pharmacist. The module will encompass the legal, ethical, and professional challenges faced by pharmacists in their working environment. It will also help raise awareness of the importance and necessity of lifelong learning. |

| Module Aim | This module aims to help students develop their knowledge, skills, and attributes in CCF Domain 1, Professional Practice. |

| Learning Outcomes |

|

| Structure and Content | Indicative syllabus/content Week 1:

Week 2:

Week 3:

|

| Learning Time | Each week students will have a combination of learning online and in their placement setting. Students will spend 30 h per week learning in their placement, and this will be supported by 10 h of directed study (online learning activities, completing core and recommended reading, and completing assessment activities). Students will also be expected to complete self-directed learning activities of 10 h per week. |

| Assessment | Case-based Online Assessment [100%]

CA sign-off on Level 3 in relevant behaviours listed above by the end of the 4-month placement |

| Indicative Reading | See ‘full’ module descriptor—Includes two core references |

| (a) Scenario/case development [18,20,21]. |

|

| (b) Question posed at the end of the scenario (September 2018). |

|

| (c) Development of 12 Action options for use in the first Module [18,20,21] | 12 action options are required for each case. In order to facilitate variation of options in subsequent years, Module coordinators are encouraged to prepare a minimum of 18 (6 × 3) when first developing a case. Development of the 12 options is not intended to be a ‘scientific’ process, rather that the action options are approximately equivalent and/or that none is obviously better than the other three and ordering of the 12 behaviours in the final ‘learning and assessment’ presentation is not random. Options are dispersed throughout (a) to (l), front loading from the ‘personal interest’ category, and ‘back-loading’ slightly from the ‘societal best interests’ options.

|

| Year 4: Professional Practice Module 190228v2.0 CR/LS/ML | Rubric for Individual Component: Individual Constructivism, Critical and Integrative Thinking and Reflective Practice are Emphasised. | Total: 50% of Module MARKS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria (Weighting is 10% per Criterion) | Exceptional Level 5 × 5 | Excellent Level 4 × 5 | Very Good Level 3 × 5 | Borderline Level 2 × 5 | Limited Level 1 × 5 | Unacceptable Level 0 × 5 | Aligned with Learning outcome Numbers |

| Identifies Professional/Ethical concepts in the scenario and what leads to a dilemma, and critical review in a professional manner. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation | Comprehensive and accurate coverage of the concepts in the scenario, and the dilemma itself and clear linkage with values in the CoC, frameworks for decision-making, relevant legislation and issues of consent and confidentiality as appropriate. | Accurate and well informed regarding concepts in the scenario and the dilemma itself and links with CoC or frameworks for decision-making with some omissions or errors. | Generally accurate with respect to identification of concepts with some omissions or errors. Poor linkage with CoC, frameworks for decision-making or legislation as appropriate. Or posts to group’s forum <24 h ‘late’ | Does not directly address the concepts, the dilemma or link with CoC, frameworks for decision-making or legislation as appropriate. Or posts to group’s forum >24 h ‘late’ | Does not address the concepts in the dilemma. Or does not answer the question(s) posed. Or does not post to group’s forum. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

| Makes and justifies decisions in a manner that reflects the statutory Code of Conduct for pharmacists and pharmacy and medicines law. (CCF) | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation | Answers the question, offers a critical analysis of the scenario and justifies action choice in an integrated, logical, and relevant manner. Wordcount: 230–270 | Answers the question, offers some analysis of the scenario and justifies action choice in a relevant manner. Wordcount: 230–270 | Answers the question and offers some analysis of the scenario without specifically justifying the choice made. WC: <230 or >270 | Answers the question(s), relating answers to questions posed, but states own opinions and choices rather than seeking to explain a reasoned action option. WC: <200 or > 300 | No evidence of trying to develop a reasoned approach to choosing and justifying an action option. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

| Action choices aligned with ‘expert’ view. (i.e., student rates and ranks action options provided). | Completes activity and posts to group’s forum by the deadline(s) and both top rank choices align with expert view. | This grade is not an option for this criterion | Completes activity and posts to group’s forum by the deadline(s) and one top rank choice aligns with expert view. | Completes & posts to group’s forum within 24 h of deadline, and one top rank choice aligns with expert view. | Completes & posts to group’s forum more than 24 h after deadline, and neither top rank choice aligns with expert view. | Does not complete or does not post to group’s forum. | 4, 7 |

| Take your choice of least preferred option and explain how a pharmacist might justify this choice as a preferred course of action. (100 words) | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | Demonstrates understanding of how poor professional decision-making might arise and how pharmacists might try to justify same. Wordcount: 90–110. | Demonstrates understanding of how poor professional decision-making might arise or how pharmacists might try to justify same. Wordcount: 90–110. | States examples of alternate decisions that might be taken without specifying how pharmacists might try to justify same. Or posts to group’s forum <24 h ‘late’. WC: <90 or >110 | Gives one example of an alternate decision that might be taken but does not clarify how a pharmacist might try to justify same. Or posts to group’s forum >24 h ‘late’. WC: <80 or >120 | Examples of alternate actions /justifications are not plausible in the context of pharmacy practice. Or does not post to group’s Forum. | 2, 5, 6 |

| Reflects on own initial response to the scenario in the context of the 12 action options provided plus general reflection in the intervening two days. Refer to Learning Unit 3, Lifelong Learning. 150 words | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation | Critical reflection: This form of reflection shows, in addition to dialogic reflection, evidence that the learner is aware that the same actions and events may be seen in different contexts, and that the different contexts may be associated with different explanations. Wordcount: 135–165 | Dialogic reflection: This writing suggests that there is a ‘stepping back’ from the events and actions which leads to a different level of discourse. There is a sense of discourse with the ‘self’ and an exploration of the role of the ‘self’ in events and actions. The quality of judgements and of possible alternatives for explaining and hypothesising are also considered. The reflection is analytical or integrative, linking factors and perspectives. Wordcount: 135–165 | Descriptive reflection: This is a description of events, that also shows some evidence of deeper consideration … but in relatively descriptive language. There is no real evidence of the notion of alternative viewpoints in use. Or posts to group’s forum <24 h ‘late’. WC: <135 or >165 | Descriptive writing: This is a description of events …. It does not show evidence of reflection. Note: Some parts of a reflective account will need to describe the context—but in the case of ‘descriptive writing’, the writing does not go beyond description. Or posts to group’s forum >24 h ‘late’ WC: <120 or >180 | Does not complete the reflection. Or does not post to group’s forum. | 1, 3, 8 |

| Year 4, Professional Practice Module 190229v2.0 CR/LS/ML | Rubric for Group/Teamwork Component (accounts for 50% of marks); Emphasis on Social Constructivism, Professionalism, and Peer Review | Total 50% of Module Marks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria (Weighting is 10% per criterion) | Exceptional Level 5 × 5 | Excellent Level 4 × 5 | Very Good Level 3 × 5 | Borderline Level 2 × 5 | Limited Level 1 × 5 | Unacceptable Level 0 × 5 | Aligned with Learning Outcomes |

| Strategy to address the scenario posted to include: Content, appropriateness of advice, structure and referencing, Note 1: Referencing is to be Vancouver style. References are not included in ‘wordcount’ calculation. Note 2: For this criterion, the same mark will be awarded to all group members. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | Comprehensive, accurate, and well-informed overage of the concepts in the scenario/dilemma. The group provides cogent, well-reasoned ‘advice’, derived from the evidence base, to the pharmacist. References are of a high standard and are well integrated with the advice (Vancouver style). Wordcount (WC): 450–550 words | Accurate and well informed regarding concepts in the dilemma. The group posts appropriate ‘advice’ to the pharmacist References are of a high standard but not integrated with the argument (Vancouver style). WC: 450–550 | Occasional omission of key factors that should be addressed in response to the scenario presented. Advice provided meets minimal standard. References are provided, but are of a minimal standard. Advice posted after the deadline, but within the same day. WC: <450 or >550 | Omission of many of the key factors that should be addressed in response to the scenario presented. Or advice provided is not of minimal standard. Or referencing is absent or of a very poor standard. Or advice is posted after the due date, but up to 24 h after due date. WC: <400 or >600 | Advice has not been posted within 24 h after due date. Or advice failed to fulfil any of the module learning outcomes. | 1, 2, 3, 7, 8 |

| Demonstrates professionalism and observes netiquette when preparing 500 words of advice, and when ranking action options as a group. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | The group at all times engaged in the consideration of the scenario in a highly professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | The group generally engaged in the consideration of the scenario in a mostly professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | The group intermittently engaged in the consideration of the scenario in a professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | Significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which is recognised, but not satisfactorily addressed within the group discussion. | Significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which does not appear to have been recognised. Or not submitted. | 1, 2, 3, 8 |

| Achieves reasoned consensus regarding most and least preferred action options in order of preference, using a clearly defined process. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | Achieves reasoned consensus regarding most and least preferred actions (3 of each), using a clearly defined process. | Achieves reasoned consensus regarding most and least preferred actions (3 of each) with tendency to use ‘voting’ to reach decision(s) (as opposed to using voting to inform decision-making process. | Achieves reasoned consensus regarding most and least preferred actions (3 of each) without clearly identifying ranking. | Achieves consensus regarding most and least preferred action options in order of preference. Any individual student contributions are minimal and are independent of group discussion and do not demonstrate reflective listening. | Group does not post all 6 choices by the due date Any individual student failing to make 3 contributions to the discussion, to the minimum standard required. | 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 |

| Group undertakes and agrees Peer Review A in a manner that demonstrates professionalism and observes netiquette Note that: Learning Unit 7, ‘Being Professional’, includes guidance on peer review. This peer review activity should reflect expectations outlined in Criterion 1 of this rubric. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | Provides a specific, targeted, realistic, implementable sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Provides a specific, targeted, realistic, implementable sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group at all times engaged in the peer review process in a highly professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | Provides an appropriate sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Provides an appropriate sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group generally engaged in the peer review process in a mostly professional, patient focused and dignified manner. | Provides a specific, but non-implementable sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Or provides a non-specific sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group intermittently engaged in the peer review process in a professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | Provides feedback that is not specific, is unrealistic and is non-implementable. Or significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which is recognised, but not satisfactorily addressed within the group discussion. | Doesn’t provide feedback. Or significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which does not appear to have been recognised. | 1, 3, 4, 5, 8 |

| Group undertakes and agrees Peer Review B in a manner that demonstrates professionalism and observes netiquette. Note that: Learning Unit 7, ‘Being Professional’, includes guidance on peer review. This peer review activity should reflect expectations outlined in Criterion 1 of this rubric. | Answer fulfils all requirements for a level 4 answer and, in addition, is exceptional in its overall arguments and presentation. | Provides a specific, targeted, realistic, implementable sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Provides a specific, targeted, realistic, implementable sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group at all times engaged in the peer review process in a highly professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | Provides an appropriate sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Provides an appropriate sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group generally engaged in the peer review process in a mostly professional, patient focused, and dignified manner. | Provides a specific, but non-implementable sentence of ‘reinforcing’ feedback. Or provides a non-specific sentence of ‘how advice might be improved’. The group intermittently engaged in the peer review process in a professional, patient-focused, and dignified manner. | Provides feedback that is not specific, is unrealistic and is non-implementable. Or significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which is recognised, but not satisfactorily addressed within the group discussion. | Doesn’t provide feedback. Or significant breach of netiquette on an individual or collective basis which does not appear to have been recognised. | 1, 3, 4, 5, 8 |

| Week | Learning and assessment activity/-ies |

|---|---|

| OW | Student access to all VLE functionality required for activities and assessment are confirmed during OW including:

|

| Moduleweek 1 |

|

| Moduleweek 2 |

|

| Module week 3 |

|

| Module week 4 |

|

| Module week 5 |

|

References

- Pharmacy Act. 2007. Available online: http://www.oireachtas.ie/documents/bills28/acts/2007/a2007.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (PSI). Interim Accreditation Standards for the Level 9 Master’s Degree Awarded on the Successful Completion of The National Pharmacy Internship Programme. 2010. Available online: https://www.thepsi.ie/Libraries/Consultations/Interim_Accreditation_Standards.sflb.ashx (accessed on 24 April 2019).

- Wilson, K.; Langley, C. Pharmacy Education and Accreditation Reviews (PEARs) Project. Report Commissioned by the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland. 2010. Available online: https://www.thepsi.ie/Libraries/Education/PEARs_Project_Report.sflb.ashx (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (PSI). Accreditation Standards for the Five-Year Fully Integrated Master’s Degree Programmes in Pharmacy. 2014. Available online: https://www.thepsi.ie/Libraries/Education/5Yr_Prog_Accreditation_Standards_FINALApproved_03102014.sflb.ashx (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (PSI). Core Competency Framework for Pharmacists. Available online: https://www.thepsi.ie/gns/Pharmacy_Practice/core-competency-framework.aspx (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (Education and Training) (Integrated Course) Rules 2014 [S.I. No. 377 of 2014]. Available online: https://www.thepsi.ie/Libraries/Legislation/SI_2014_0377_PSI_Education_and_Training_Integrated_Course_Rules_2014.sflb.ashx (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (Education and Training) (Integrated Course) Rules 2017 [S.I. No. 97 of 2017]. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2017/si/97/made/en/pdf (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- European Commission (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS)). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/resources-and-tools/european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system-ects_en (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- General Level Framework, a Framework for Pharmacist Development in General Pharmacy Practice, 2nd ed.; Competency Development and Evaluation Group (CoDEG): London, UK, 2007; Available online: http://www.codeg.org/fileadmin/codeg/pdf/glf/GLF_October_2007_Edition.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2019).

- Hussey, T.; Smith, P. The uses of learning outcomes. Teach. High. Educ. 2003, 13, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treleaven, L.; Voola, R. Integrating the development of graduate attributes through constructive alignment. J. Mark. Educ. 2009, 30, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Constructing learning by aligning teaching: Constructive alignment. In Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 2nd ed.; SRHE and Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2004; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Huball, H.; Burt, H. An integrated approach to developing and implementing learning centred curricula. Intern. J. Acad. Dev. 2004, 1, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini Reddy, Y.; Andrade, H. A review of rubric use in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods; Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, S.; Teunissen, P.W.; Dornan, T. Experiential learning: Transforming theory into practice. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rest, J.; Narvaez, D.; Bebeau, M.J.; Thoma, S.J. Postconventional Moral Thinking: A Neo-Kohlbergian Approach; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, S.J.; Bebeau, M.J.; Bolland, A. The role of moral judgment in context—Specific professional decision making. In Getting Involved: Global Citizenship Development and Sources of Moral Values; Sense Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bebeau, M.J.; Thoma, S.J. “Intermediate” concepts and the connection to moral education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 11, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, C.; Thoma, S.J.; Grimes, T.; Radomski, M. Promoting peer debate in pursuit of moral reasoning competencies development: Spotlight on educational intervention design. Innov. Pharm. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, C.; Thoma, S.J. Insights from the defining issues test on moral reasoning competencies Development in community pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, C.; Thoma, S.; Wingfield, J. From workshop to E-Learning: Using technology-enhanced “Intermediate Concept Measures” as a framework for pharmacy ethics education and assessment. Pharmacy 2014, 2, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, N.; Smith, D. Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1995, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. Reflection in Learning and Professional Development; Kogan: Lonfon, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schon, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Towards a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions; Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S. Student facilitators’ habits of mind and their influences on higher-level knowledge construction occurrences in online discussions: A case study. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2011, 48, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrastinski, S. A theory of online learning as online participation. Comput. Educ. 2009, 52, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palloff, R.M.; Pratt, K. Assessing the Online Learner: Resources and Strategies for Faculty; Jossey Bass: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sthapornnanon, N.; Sakulbumrungsil, R.; Theeraroungchaisri, A.; Watcharadamrongkun, S. Social constructivist learning environment in an online professional practice course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Assessment of/for/as Learning: Principles. Dublin, Ireland, 2016. Available online: https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/resource-hub/student-success/assessment-of-for-as-learning/#!/Principles (accessed on 28 April 2018).

- Amin, Z.; Boulet, J.R.; Cook, D.A.; Ellaway, R.; Fahal, A.; Kneebone, R.; Maley, M.; Ostergaard, D.; Ponnamperuma, G.; Wearn, A.; et al. Technology-enabled assessment of health professions education: Consensus statements from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norcini, J.; Anderson, B.; Bollela, V.; Burch, V.; Costa, M.J.; Duvivier, R.; Galbraith, R.; Hays, R.; Kent, A.; Perrott, V.; et al. Criteria for good assessment: Consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaefli, A.; Rest, J.R.; Thoma, S.J. Does moral education improve moral judgment? A meta-analysis of intervention studies using the Defining Issues Test. Rev. Educ. Res. 1985, 55, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, W.Y. Teaching ethics—A direct approach. J. Moral Educ. 1990, 19, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, R.G.; Arbaugh, J.B. Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, R.M.; Kuh, G.D.; Klein, S.P. Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.M.; Kuh, G.D. Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Res. High. Educ. 2004, 45, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Handley, K.; Millar, J.; O’Donovan, B. Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assess Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vai, M.; Sosulski, K. Essentials of Online Course Design: A Standards Based Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ellaway, R.; Coral, J.; Topps, D.; Topps, M. Exploring digital professionalism. Med. Teach. 2015, 37, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.; Hyland, A.; Ryan, N. Implementing Bologna in Your Institution. Writing and Using Learning Outcomes: A Practical Guide. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238495834_Writing_and_Using_Learning_Outcomes_A_Practical_Guide (accessed on 28 April 2019).

- Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI). Irish National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ). Dublin, Ireland, 2012. Available online: https://www.qqi.ie/Articles/Pages/National-Framework-of-Qualifications-%28NFQ%29.aspx (accessed on 28 April 2019).

| Domain | Competency |

|---|---|

| Professional practice | Practises ‘patient-centred’ care Practises professionally Practises legally Practises ethically Engages in appropriate continuing professional development |

| Personal skills | Leadership skills Decision making skills Team working skills Communication skills |

| Supply of medicines | Manufactures and compounds medicines Manages the medicines supply chain Reviews and dispenses medicines accurately |

| Safe and rational use of medicines | Patient consultation skills Patient counselling skills Reviews and manages patient medicines Identifies and manages medication safety issues Provides medicines information and education |

| Public health | Population health Health promotion Research skills |

| Organisation and management skills | Self-management skills Workplace management skills Human resources management skills Financial management skills Quality assurance |

| Level | Rating | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| N/A | Cannot | Student not exposed to this behaviour in the training establishment. |

| 1 | Rarely | Very rarely meets the standard expected. No logical thought process appears to apply. |

| 2 | Sometimes | Rarely meets the standard expected. Much more haphazard than “mostly”. |

| 3 | Mostly | Standard practice usually met with occasional lapses. |

| 4 | Consistently | Demonstrates the expected standard practice with rare lapses. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roche, C.; Flood, M.; Lynch, M.; Sahm, L.J. Balancing Assessment with “In-Service Practical Training”: A Case Report on Collaborative Curriculum Design for Delivery in the Practice Setting. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030093

Roche C, Flood M, Lynch M, Sahm LJ. Balancing Assessment with “In-Service Practical Training”: A Case Report on Collaborative Curriculum Design for Delivery in the Practice Setting. Pharmacy. 2019; 7(3):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030093

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoche, Cicely, Michelle Flood, Matthew Lynch, and Laura J. Sahm. 2019. "Balancing Assessment with “In-Service Practical Training”: A Case Report on Collaborative Curriculum Design for Delivery in the Practice Setting" Pharmacy 7, no. 3: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030093

APA StyleRoche, C., Flood, M., Lynch, M., & Sahm, L. J. (2019). Balancing Assessment with “In-Service Practical Training”: A Case Report on Collaborative Curriculum Design for Delivery in the Practice Setting. Pharmacy, 7(3), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7030093