Pharmacy Practice and Education in Finland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Design

- pharmacy:

- ○

- practice (community, hospital, and industrial);

- ○

- legislation;

- ○

- education and training;

3. Evaluation and Assessment

3.1. Organization of the Activities of Pharmacists, Professional Bodies

3.2. Pharmacy Faculties, Students, and Courses

3.3. Teaching and Learning Methods—Student Hours

3.4. Subject Areas

3.5. Impact of the Bologna Principles [3]

3.6. Impact of European Union (EU) Directive 2013/55/EC [2]

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- University education will have

- ○

- a first-cycle degree (undergraduate, three years) with “international recognition of the first cycle degree as an appropriate level…”, providing the qualifications needed for immediate employment.

- ○

- the above will be followed with a Master degree (M.Sc., two years), and eventually a Ph.D. degree (four years)

- Qualifications in both cycles can be obtained in several EU countries; in an “extreme” case (going beyond the typical case of a semester spent abroad), a foreign B.Sc. could be accepted as a requirement for acceptance into the Finnish M.Sc. program.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkinson, J.; Rombaut, B. The 2011 PHARMINE report on pharmacy and pharmacy education in the European Union. Pharm. Pract. 2011, 9, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Commission Directive 2013/55/EU on Education and Training for Sectoral Practice Such as That of Pharmacy. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/?uri=celex:32013L0055 (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- The European Higher Education Area (EHEA)—Bologna Agreement of Harmonisation of European University Degree Courses. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Medicines Policy. Available online: https://stm.fi/en/pharmaceutical-service (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. Social Expenditure. Available online: https://stm.fi/en/expenditure (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Erasmus Programme for Student and Staff Exchange in the EU. Available online: https://info.erasmusplus.fr/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Atkinson, J. The Country Profiles of the PHARMINE Survey of European Higher Educational Institutions Delivering Pharmacy Education and Training. Pharmacy 2017, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnish Medicine’s Agency (FIMEA). Available online: https://www.fimea.fi/web/en (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- EFPIA—The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations: The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures, Key Data 2017. Available online: https://www.efpia.eu/publications/downloads/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Akava—Confederation of Unions for Professional and Managerial Staff in Finland in 2008. Available online: http://www.akava.fi/files/771/Akavalaiset_tyomarkkinat_2008.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2019). (In Finnish).

- Valvira (National supervisory authority for Welfare and Health). Available online: https://www.valvira.fi/web/en (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- AFP (Pharmacy Owners’ Association). Available online: https://www.apteekkariliitto.fi/en/association.html (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- SFL (Finnish Pharmacists’ Association). Available online: https://www.farmasialiitto.fi (accessed on 15 December 2018).

- Language Requirements in Finnish or Swedish for B. Sc. and M. Sc. Degrees. Available online: https://www.helsinki.fi/en/admissions/proving-your-language-skills (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Courses Taught in English in Helsinki. Available online: https://guide.student.helsinki.fi/en (accessed on 5 February 2019).

| Item | Number | Comments. |

|---|---|---|

| Community pharmacists | 772 M.Sc. pharmacists + 594 pharmacy owners = 1366 | There are additionally 3724 bachelor-level pharmacists working in community pharmacies. The total number of employees in community pharmacies is circa 8500. |

| Community pharmacies | 610 + 200 = 810 | 610 pharmacies and 200 subsidiary or branch pharmacies—the same medicines and services are available from both types of pharmacies. There are approximately 1 pharmacist (M.Sc.) and 4.5 bachelor pharmacists per pharmacy, and 6600 inhabitants per pharmacy. |

| Competences and roles of community pharmacists | Pharmacists work as the following:

Pharmacists provide services to help patients monitor the therapeutic control of blood sugar or blood pressure. | |

| Ownership limited to pharmacists? | Yes | A license to own a pharmacy is granted to a person having a 5-year degree in pharmacy with a 6-month traineeship (M.Sc. Pharm.). |

| Are there rules governing the geographical distribution of community pharmacies? [8] | Yes | The location of community pharmacies is based on the decision made by the Finnish Medicine’s Agency (FIMEA) (https://www.fimea.fi/web/en). FIMEA evaluates if there is a need for one (or multiple) community pharmacies in some particular area and specifies also the area where the pharmacy or pharmacies should be located. Within that specific area, pharmacies are free to choose their exact location. This system assures equal accessibility to medicines and pharmacy services for the whole population. |

| Are drugs and healthcare products available to the general public by other channels? | No | In Finland, medicines are sold to the public only from pharmacies, with the exception that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products may also be available in grocery shops. However, many pharmacies offer internet shop alternatives for healthcare products and over-the-counter drugs. Veterinary drugs are also available from veterinarians. |

| Item | Number | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Are persons other than pharmacists involved in community practice? | Yes | These are pharmacy technicians. Only persons with either a B.Sc.Pharm. or a M.Sc.Pharm. degree are allowed to dispense and counsel patients on medicines. A pharmacist (M.Sc.degree) is responsible for the operation of the pharmacy. |

| Their titles and number(s) | 3486 | Pharmacy technicians with upper secondary vocational education (corresponds to “pharmacy assistants”) |

| Their qualifications | ||

| Organization providing and validating the education and training. | Upper secondary vocational education | |

| Duration of studies | 2–3 years | |

| Subject areas | Pharmacy technicians study logistics, accounting, and information technology (IT) skills. Education consists of theoretical studies and a larger part of in-house training. | |

| Competences and roles | Pharmacy technicians: Their main task is to take care of medicine storage and logistics in the community pharmacy. They also take care, for example, of invoicing and operating of pharmacy IT systems. |

| Item | Number | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Number of hospital pharmacists | 696 | 605 (B.Sc.) + 91 (M.Sc.) |

| Number of hospital pharmacies | 154 | There are 24 hospital pharmacies that are in central hospitals and 81 medicine centers which are in other hospitals or healthcare centers. University hospitals are the largest hospitals in Finland. There are five university hospitals that are located in the bigger cities (Helsinki, Tampere, Turku, Oulu, and Kuopio: in cities where there is a university with a medical faculty). Central hospitals are the most central and larger hospitals in some other particular hospital districts. Each central hospital is under the supervision of a given university hospital. |

| Competences and roles of hospital pharmacists | In most hospitals, the hospital pharmacy or the medicine center is one of the medical service departments. The manager of a hospital pharmacy is required to have an M.Sc. in pharmacy, while the manager of a medicine centre is required to have an M.Sc. or B.Sc. in pharmacy. A manager of a hospital pharmacy or a dispensary is usually authorized by the medical director of the hospital. B.Sc. and M.Sc. hospital pharmacists used to have a logistic role in hospitals and healthcare centers. The role is now starting to change, and some pharmacists are working in the wards. A professional post-graduate specialization program for hospital pharmacists started in 2010 to ensure stronger competencies for the hospital pharmacists to work as clinical specialists (see more details of the specialized education in Table 7). |

| Pharmaceutical and Related Industries | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | Number | Comment |

| Number of companies with production, research and development (R&D) and distribution | 4 | Pharmaceutical production: 1598 million € (m€) Pharmaceutical exports: 852 m€; imports: 2010 m€ (balance −1158 m€) Research and development: 172 m€ Employment in the pharmaceutical industry: 5233 Pharmaceutical market value: 2246 m€ Share of generics in market sales: 25% The above figures are from The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures, European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations, EFPIA, Key figures 2017 [9]. |

| Companies with production only | 3 | |

| Companies with distribution only | 2 | |

| Number of pharmacists working in industry | 400 M.Sc. and 400 B.Sc. | |

| Other sectors | ||

| Number of pharmacists working in other sectors | 320 | This information is based on the report by Akava—Confederation of Unions for Professional and Managerial Staff in Finland in 2008 [10]. |

| Sectors in which pharmacists are employed | Academic sector, e.g., pharmacists working in universities and research organizations (160) Administration, e.g., pharmacists working in Finnish national authorities (Finnish Medicines Agency, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, National Insurance Institution) (60) Other: unspecified (100) | |

| Competences and roles of pharmacists employed in other sectors | Teaching, research, administration, management, and leadership Varying roles and competencies: specialist pharmacists (pharmacists specialized in some specific issues, for example, marketing authorizations, pricing and re-imbursement of medical products, IT-issues such as e-prescriptions and databases, medicine information), researchers, managers | |

| Item | Reply | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Registration of pharmacists | Yes. There are circa 2000 registered pharmacists in Finland. | Issued by Valvira (National supervisory authority for Welfare and Health) [11]. |

| Creation of community pharmacies and control of territorial distribution | Yes | Issued by Finnish Medicines Agency (FIMEA) [8]. From the FIMEA website: Under Section 40 of the Medicines Act, the operation of a pharmacy business requires a licence (pharmacy licence) issued by FIMEA. The conditions under which a pharmacy licence may be granted according to the Section 43 of the Medicines Act are as follows: “A pharmacy licence may be granted to citizen of a European Economic Area state who is a certified Master of Pharmacy and who has not been declared bankrupt or legally incompetent or who has not been assigned a person to supervise his or her interests. If there is more than one applicant, a pharmacy licence is granted to the applicant who can be considered to have the overall best potential for operating a pharmacy business. In assessing the potential, the applicant’s work in pharmacies and other pharmaceutical services and studies, managerial skills, and other activities pertinent to operating a pharmacy business must be taken into account.” |

| Ethical considerations and role of pharmacists in healthcare | Yes | There is an advisory board on ethical issues in pharmacies based on the co-operation between Pharmacy Owners’ Association (AFP [12]) and Finnish Pharmacists’ Association (SFL [13]). Additionally, there exists a national ethical code of conduct produced by abovementioned organizations. In order to strengthen the role of community pharmacies in healthcare and to support the professional development, the Association of Finnish Pharmacists established a national strategy in 1997 that concerned pharmacy services and pharmacy role in healthcare. This strategy highlighted the importance of medication counseling in community pharmacies: whenever medicines are dispensed, information should also be provided. National long-term programs focusing on chronic diseases (asthma, diabetes, and heart diseases) were organized to encourage local co-operation between pharmacies and other healthcare professionals and to develop the competency and counseling skills of pharmacy staff. |

| Quality assurance and validation of higher-education institution (HEI) courses for pharmacists | No | The universities providing pharmacy education have their own quality handbooks and quality assurance procedures. In the University of Helsinki, for example, feedback is collected from students and internal and external/international audits are made regularly. |

| Item | Reply and/or Number | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of HEIs for pharmacy | 3 | Helsinki, Kuopio, Turku. In total, there are 14 universities and 23 universities of applied sciences in Finland. |

| Public HEIs | 3 | |

| Organization of HEIs | ||

| Independent faculty | Yes | University of Helsinki, Faculty of Pharmacy |

| Attached to a medical faculty | Yes | University of Eastern Finland, Faculty of Health Sciences, in Kuopio |

| Attached to a science faculty | Yes | Åbo Akademi University, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, in Turku |

| Do HEIs offer B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees? | Yes | Universities of Helsinki and Eastern Finland |

| Do HEIs offer a M.Sc. Pharm. after a B.Sc. degree in another discipline? | Yes | |

| Finland | ||

| Teaching staff | ||

| Number of teaching staff (from Finland) | circa 260 | |

| Number of international teaching staff (from European Union (EU) MSs) | circa 30 | |

| Number of international teaching staff (non-EU) | circa 20 | |

| Number professionals (pharmacists and others) from outside the HEI, involved in education and training. | circa 50 | |

| Students | ||

| Places on entry after secondary school | 350 + 110 | The numbers are rounded. All students follow the same course for the first 3 years with 350 having the right to study only B.Sc. Pharm. (and taking up employment after graduating), and 110 going on for two further years to a M.Sc. Pharm. |

| Number of applicants for entry | 3000 | Approximately 6 applicants for 1 place. |

| Number that become professional pharmacists. | 350 B.Sc. + 110 M.Sc. | Around 350 take up employment after graduating B.Sc. and do not have the right to continue with the M.Sc. course. Around 110 continue with the M.Sc. course. |

| Number of international students (from EU member states (MS)) | circa 75 | Exchange students, mostly M.Sc. students |

| Number of international students (non-EU) | circa 20 | Exchange students, mostly M.Sc. students |

| Entry requirements following secondary school (national) | ||

| Specific pharmacy-related, national entrance examination | Yes | The same national entrance examination in pharmacy is used in all HEIs. |

| Is there a national numerus clausus? | No | Each institution sets its individual numerus clausus. |

| Advanced entry | ||

| At which level? | Some of the students have the right to pursue both B.Sc. and M.Sc. (Pharm.) degrees. Persons taken the B.Sc. (Pharm.) degree can apply to the Master’s level also later. | |

| Specific requirements for international students (EU or non-EU). | Language requirements in Finnish or Swedish for B.Sc. and M.Sc. | |

| Fees per year | ||

| For home students | 0 | There are no tuition fees for national or international B.Sc. and M.Sc. (Pharm.) degree students. |

| For EU MS students | 0 | |

| For non-EU students | 0 | |

| Helsinki | ||

| Teaching staff | ||

| Number of teaching staff (from Finland) | circa 120 | |

| Number of international teaching staff (from EU MSs) | circa 20 | |

| Number of international teaching staff (non-EU) | circa 20 | |

| Number professionals (pharmacists and others) from outside the HEIs, involved in education and training. | circa 25 | |

| Students | ||

| Places on entry after secondary school | 143 + 60 | All students follow the same course for the first 3 years with 143 having the right to study only B.Sc. Pharm. (and taking up employment after graduating), and 60 going on for two further years to a M.Sc. Pharm. |

| Number of applicants for entry | 1500 | Approximately 7 candidates per place. |

| Number becoming professional pharmacists. | 150 + 50 | |

| Number of international students (EU) | 50 | Exchange students, mostly M.Sc. students |

| Number of international students (non-EU) | 10 | Exchange students, mostly M.Sc. students |

| Entry requirements following secondary school | ||

| HEI has a specific pharmacy-related entrance examination | Yes | The same national entrance examination in pharmacy is used in all HEIs. |

| Advanced entry | ||

| At which level? | Some of the students have the right to pursue both B.Sc. and M.Sc. (Pharm.) degrees. Persons taken the B.Sc. (Pharm.) degree can apply to the Master’s level also later. | |

| Specific requirements for international students (EU/non-EU). | Language requirements in Finnish or Swedish for B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees [14]. For exchange students no specific language requirements. The courses taught in English in Helsinki are listed in Reference [15]. | |

| Fees per year | Free for all B.Sc. and M.Sc. (Pharm.) degree students. | |

| Item | Reply and/or Number | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Does your HEI provide specialized courses? | Yes | |

| In which years? | Both after completing the B.Sc. and the M.Sc. degree | |

| In which specialization (industry, hospital…)? | 1. Industrial pharmacy 2. Community and hospital pharmacy Specialization studies are post-graduate programs for pharmacists (both M.Sc. and B.Sc. Pharm.) working in these specialization areas. Studying takes place alongside work and study plan is tailored individually to support the student’s own development needs. The extent of studies is 60 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) for M.Sc. (Pharm.) and 40 ECTS for B.Sc. (Pharm.). Normative duration of studies is 3–4 years. The student fee is 6000 € for the M.Sc. graduates in Pharm. and 4000 € for the B.Sc. graduates in Pharm. (ca. 1500 €/year). | |

| What are the student numbers in each specialization? | 20 | In both specialization programs, the yearly intake of Bachelors and Masters is altogether 20. |

| Item | Reply | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Major changes before 2019 in Helsinki/Finland? | Yes | Four new positions for tenure track professors were appointed to the Faculty of Pharmacy. The professional specialization education programs were reformed 2016. The curricula for Bachelor’s and Master’s levels were reformed 2014–2017. A new organization was introduced in the university for degree study programs. The leaders and steering groups for the Bachelor and Master study programs took action in 2016. |

| Major changes envisaged in Helsinki/Finland? | Yes | The implementation of the new curriculum as a whole in the degree programs. |

| Method | Year 1 | % | Year 2 | % | Year 3 | % | Year 4 * | Year 5 ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture | 427 | 72 | 223 | 22 | 98 | 12 | 160 | |

| Practicals | 36 | 6 | 189 | 19 | 46 | 6 | 0 | |

| Project work | 70 | 12 | 41 | 4 | 120 | 14 | 95 | |

| Subtotal | 533 | 453 | 264 | 255 | ||||

| Traineeship Community | 0 | 0 | 520 (= 13 weeks) | 52 | 520 (= 13 weeks) | 62 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 533 | 973 | 784 | 255 | ||||

| Electives: choice | 61 | 28 | 49 | |||||

| Total | 594 | 1001 | 833 |

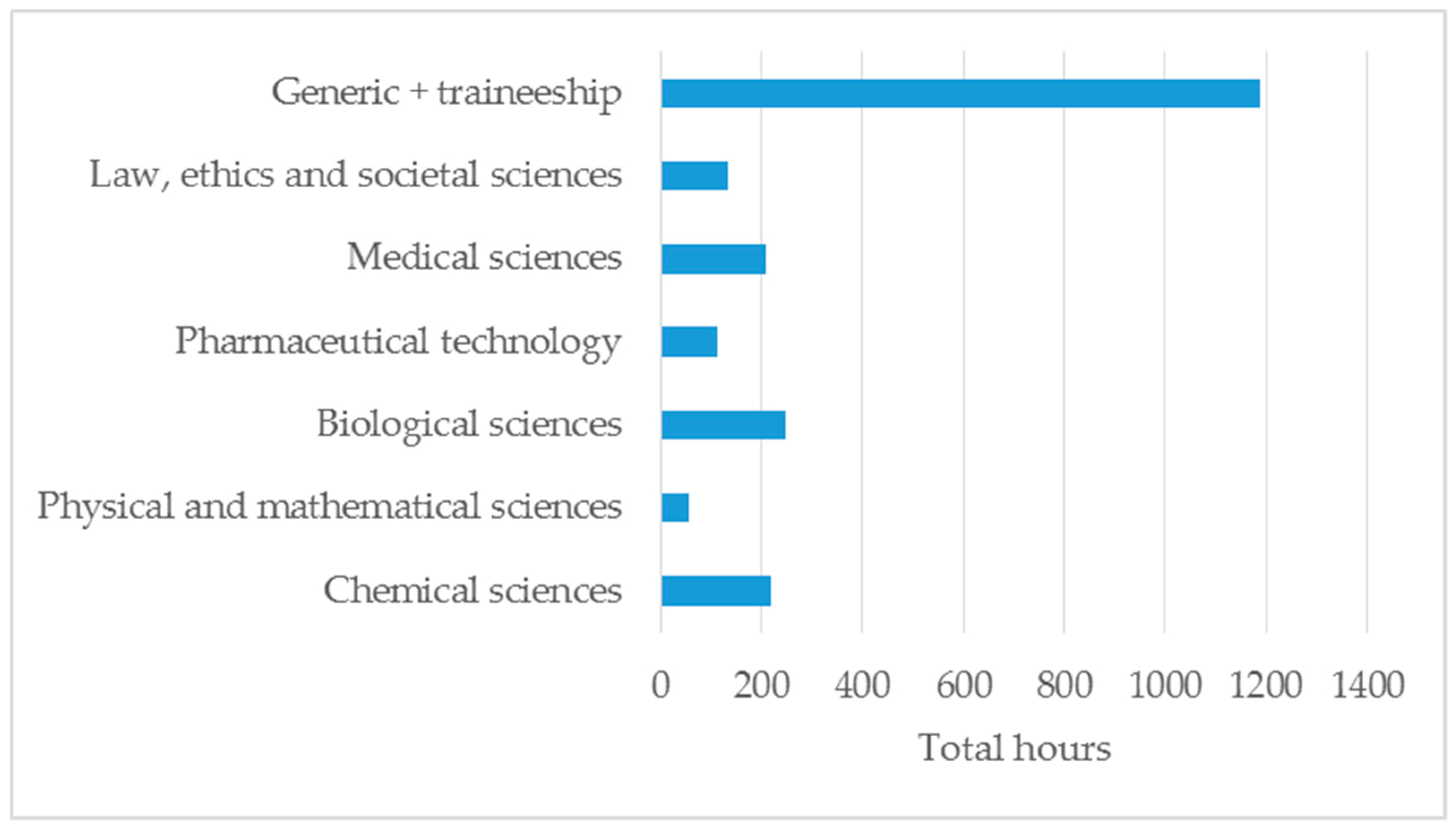

| Subject Area | Year 1 | % | Year 2 | % | Year 3 | % | Year 4 § | Total # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical sciences | 10 ECTS 112 h | 21 | 15 ECTS 108 h | 11 | 220 h | |||

| Physical and mathematical sciences | 3 ECTS 28 h | 5 | 2 ECTS 28 h | 3 | 56 h | |||

| Biological sciences | 10 ECTS 68 h | 13 | 12 ECTS 135 h | 14 | 203 h | |||

| Pharmaceutical technology | 5 ECTS 28 h | 5 | 5 ECTS 84 h | 8 | 112 h | |||

| Medical sciences | 23 ECTS 166 h | 32 | 11 ECTS 64 h | 6 | 4 ECTS 46 h | 7 | 276 h | |

| Law, ethics and societal sciences | 7 ECTS 99 h | 19 | 5 ECTS 36 h | 5 | 135 h | |||

| Generic subjects | 5 ECTS 24 h | 5 | 3 ECTS 56 h | 6 | 10 ECTS 68 h | 10 | 148 h | |

| Subtotal | 525 h | 475 h | 150 h | 255 h | 1150 h | |||

| Generic subjects + traineeship | 5 ECTS 24 h | 5 | 18 ECTS 576 h | 58 | 25 ECTS 588 h | 88 | 1188 h | |

| Total | 525 h | 995 h | 670 h | 255 h | 2445 h |

| Bologna Principle | Is the Principle Applied? | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Comparable degrees/diploma supplement | Yes | Each graduating student receives a diploma supplement in English |

| 2. Two main cycles (B and M) with entry and exit at B level | Yes | We have a 3-year Bachelor and a 2-year Master program according to the Bologna Agreement. In the University of Helsinki, entrance is permitted each year for 150 students (B.Sc.) and 55 students (M.Sc.). Bachelors graduate after 3 years, and Masters graduate after 5 years. It is possible for a person with a B.Sc. (Pharm.) to gain entrance in the M.Sc. (Pharm.) program if passing an entrance exam or on the grounds of good grades in the Bachelor level studies. Bachelors in Pharmacy are employed in Finland and Sweden in community pharmacies, hospital pharmacies, industry, etc. They constitute the main work force in Finnish community pharmacies. In other parts of Europe, the degree is not recognized. |

| 3. ECTS system of credits/links to LLL (life-long learning) | Yes | All our courses are built according to the ECTS system based on a yearly workload of 1600 h. We accept ECTSs obtained in other European countries to the full. Our students get ECTS points for the compulsory traineeship included in their degree. Since the traineeship is 6 months, the points given are 30, i.e., 5/month. All HEIs in Finland use ECTS-based credit points since 2005. The ECTSs gained before and after graduation are comparable. |

| 4. Obstacles to mobility | Yes | The biggest obstacle to student mobility is the strictly organized curriculum, which does not easily allow students to move. If they are willing to prolong their studies by a half or one year, mobility becomes much easier. In reality, this means that most of our exchange students choose to do their Master’s project abroad, because, by this stage in their university career, they have fewer compulsory courses. Language and financial considerations are not major obstacles to mobility. |

| 5. Erasmus staff exchange to HEI from elsewhere | Yes | Number of staff months: 0.25 |

| 6. Erasmus staff exchange from HEI to other HEIs | Yes | Number of staff months: 0.25 |

| 7. Erasmus student exchange to HEI from elsewhere | Yes | Number of student months: circa 250 All over Europe |

| 8. Erasmus student exchange from HEI to other HEIs | Yes | Number of student months: circa 50 |

| The Directive States | How Does/Will This Directive Statement Affect Pharmacy Education and Training? |

|---|---|

| “Evidence of formal qualifications as a pharmacist shall attest to training of at least five years’ duration…” | This statement does not apply to the first-phase B.Sc. degree in Pharmacy. This statement was obviously taken into consideration when the curriculum for the M.Sc. (Pharm.) degree was developed in 2006. |

| “…four years of full-time theoretical and practical training at a university or at a higher institute of a level recognized as equivalent, or under the supervision of a university” | Master students study 4.5 years at the university, so this requirement is fulfilled. |

| “…six-month traineeship in a pharmacy which is open to the public or in a hospital, under the supervision of that hospital’s pharmaceutical department” | Both Bachelor and Master students perform the six-month traineeship. At least three months have to be spent in a community pharmacy and the remaining three months can be spent in a community or hospital pharmacy. The first three months of traineeship are performed in the second study year and the second three months are performed during the third year. |

| “The balance between theoretical and practical training shall, in respect of each subject, give sufficient importance to theory to maintain the university character of the training” | This point was object of intensive discussion during the degree reform according to Bologna. From the university point of view, we need to place emphasis on the theoretical knowledge in order to prepare the students for further studies (Ph.D.). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirvonen, J.; Salminen, O.; Vuorensola, K.; Katajavuori, N.; Huhtala, H.; Atkinson, J. Pharmacy Practice and Education in Finland. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010021

Hirvonen J, Salminen O, Vuorensola K, Katajavuori N, Huhtala H, Atkinson J. Pharmacy Practice and Education in Finland. Pharmacy. 2019; 7(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirvonen, Jouni, Outi Salminen, Katariina Vuorensola, Nina Katajavuori, Helena Huhtala, and Jeffrey Atkinson. 2019. "Pharmacy Practice and Education in Finland" Pharmacy 7, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010021

APA StyleHirvonen, J., Salminen, O., Vuorensola, K., Katajavuori, N., Huhtala, H., & Atkinson, J. (2019). Pharmacy Practice and Education in Finland. Pharmacy, 7(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010021