Exploration of Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting in a Tertiary Health Care Facility: A Qualitative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What do nurses know about the ME and MER system?

- What are the nurses’ attitudes toward MER?

- What are the barriers which could hinder nurses from reporting their MEs?

- What are the factors which could facilitate MER among nurses?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure and Interview Process

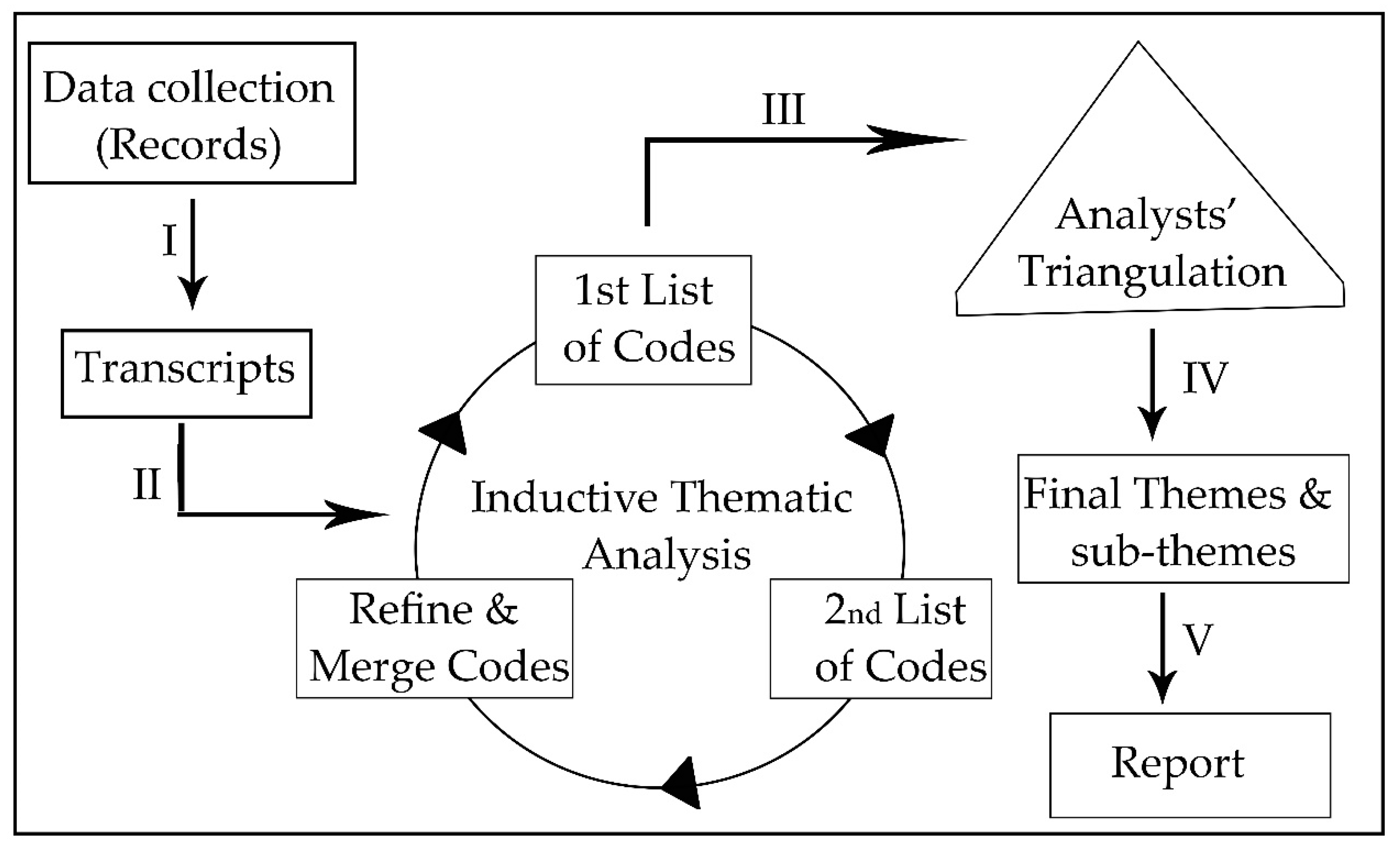

2.4. Data Analysis

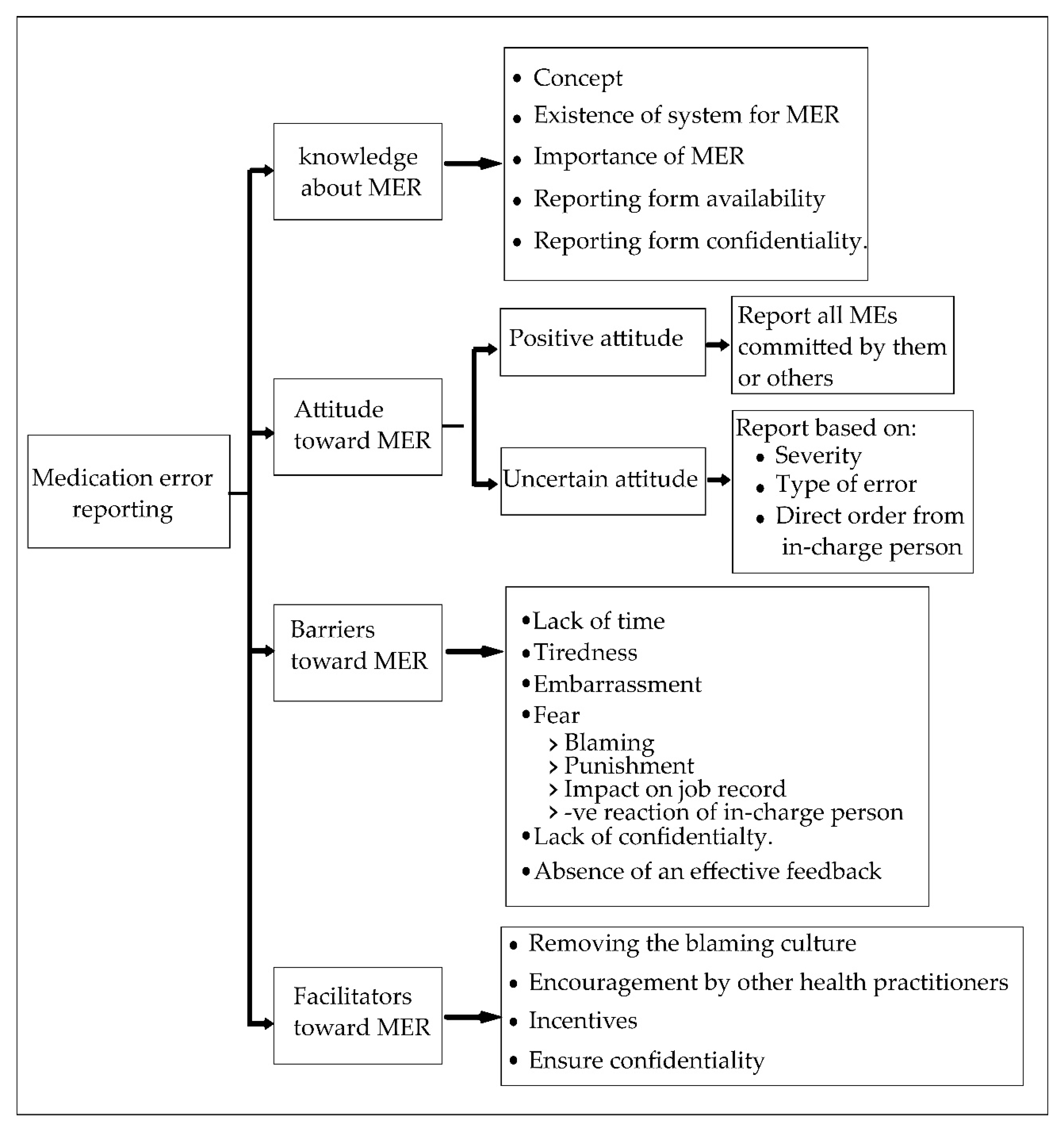

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge about MER

3.1.1. Concept of ME

“Medication error is an error when giving medication including dosage and also the type of medication, make sure to follow the 7Rs practice in the hospital.” (N1)

“Medication error is when something unwanted occurs such as wrong medication is given to the patient.” (N7)

“Medication error means giving wrong medication to the patient, which includes wrong dose, wrong route, and wrong documentation.” (N13)

3.1.2. The Existence of a System for MER and the Importance of MER

“Yes, we have a system for medication error reporting […] And, it is very important because it involves the quality of service which is being given to the patient and it is very important to monitor ME.” (N1)

“It is important because we want to improve the way of delivering care and serving the patient. To learn from reports, where and which thing can be done. So we have more information about what has been done and their consequences.” (N3)

“It is important because we want to detect what is ME and to prevent it from happening again.” (N7)

“Normally, we do root-cause analysis to find out when and how this happened. Sometimes it comes from the wrong prescription like wrong dose or wrong route or wrong frequency and then we find out how that happen and try to tackle.” (N5)

“It is to guide our practice […] Not add more error to this collection […] To avoid ME in future […] It is considered as a good resource.” (N4)

3.1.3. The Availability and Confidentiality of the Reporting Form

“The reporting form is available in the pharmacy department.” (N5)

“I have not seen the reporting form before. Because, so far, I did not make any error.” (N8)

“I have seen it; it is easy to fill, it does not need modification or re-designation.” (N1)

“The report is not too detailed like describing everything, but it underlines or highlights when the medication was given to the patient.” (N3)

3.2. Attitude of Nurses toward ME Reporting

3.2.1. Positive Attitude

“Nothing affects my decision to report, once the error occurs it should be reported.” (N4)

“It is not a matter of choice.” (N7)

“Once I detect an error, I cannot just ignore it, and I straightforward report it [...] We must make a report also because this is ME, and we must report whether it is serious or not.” (N2)

“Here in A and E department, it does not matter if the error is big, mild, or small, it must be reported.” (N8)

3.2.2. Uncertain Attitude toward ME Reporting

“If the error caused big and serious complication I have to report.” (N17)

“Based on the patient, I will see the effect on the patient first. My first concern is the patient, I will not report unless something happens to the patient. In this case, the doctor gives antidote and then there is an investigation and eventually, they will revert to me.” (N9)

“Based on the route of administration IV it should be reported.” (N18)

“I just inform the sister and the doctor, and let them choose to fill the form or not but as for investigation, I will come and join them” (N13)

“Some nurses, at first, they think about what happen and the problems associated with reporting, so they do not report.” (N12)

3.2.3. Reporting of Others’ Errors

“I will report if other staff nurse made a mistake.” (N1)

“I will report errors committed by others because this is in the best interest of the patient, and also it would help things go smooth in the future, for example, patient allergy …” (N3)

“If I made a mistake I would inform, also if others from my colleagues made a mistake, I would still inform.” (N6)

“No, I report only my errors. If my colleagues made mistakes, I would just advise her to report, but I will not report her error.” (N8)

3.3. Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting

3.3.1. Lack of Time

“We will be exposed to so many questions […] long time […] time to discuss the ME that was reported […] investigations take time. No other problems, just that it takes time to report and then questions from pharmacist or doctors. We do not have time for reporting. It is a long story and takes much time.” (N4)

“Sometimes, I decide not to report. Because, if there is an investigation we have to be presented, as you know it will take a long time and we will be all inconvenient.” (N9)

3.3.2. Tiredness

“Sometimes, we are tired. Once we are tired we decide not to report.” (N4)

3.3.3. Embarrassment

“Facing the embarrassment from my family and friends is tough. They will blame us.” (N4)

“They (family and friends) understand because these are not things that a person does on purpose. But facing them still difficult.” (N9)

3.3.4. Fear

“I fear from legal problems and disciplinary actions from the hospital.” (N8)

“Sometimes, I do not want to get into issues, I do not want people to come to ask me for investigation later.” (N2)

“If I report this will affect my record because everything will be recorded in my personal record.” (N9)

“Fearing others, especially the investigation, because in Malaysia all errors must be reported to your job record and they do disciplinary action.” (N4)

3.3.5. Negative Reaction from Sister In-Charge

“The sister will monitor me more.” (N8)

“Negative reaction from sister and matron […] they must not punish the staff, they must guide the staff and follow the staff and ensure that the stuff follows the standards.” (N4)

3.3.6. The Confidentiality of the Reporting Form

“I prefer to fill anonymous form […] Because I feel shy and would not work further. Also, I would feel sorry for the patient. So, I prefer to fill the form without names.” (N2)

“I prefer to fill the anonymous form as it is good for us. If mistakes have been done, the news of medication errors should be displayed without names being mentioned. In the future, if the people know that this person made a mistake, people would decide not to deal with this person again. This will damage the confidence of the nurse. In the future, they will not report and there will be no chance to learn from the mistakes.” (N6)

“Off course, if no names mentioned the number of reports will increase.” (N8)

3.3.7. Absence of Effective Feedback

“No one goes through all the errors and give me a feedback.” (N7)

“I did not receive any feedback for my ME report.” (19)

3.4. Facilitators to Improve ME Reporting

“Remove the blaming culture. The matron and sister in charge should guide the staff not blame them.” (N4)

“Tell the matron that if any person is involved in a medication error, she shall not be scolded.” (N7)

“There is no need to encourage us because this is our duty.” (N12)

“The sister in charge encouraged me to report.” (N9)

“Actually, among us, we as nurses encourage each other to report errors; also the sister in charge encourages us to do that.” (N8)

“Giving monetary rewards to the nurses.” (N3)

“I prefer to fill the form with no names and it is better not to include names.” (N2)

“I think as long as they can ensure the confidentiality of the person who reported, we will feel safe.” (N9)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stump, L.S. Re-engineering the medication error-reporting process: Removing the blame and improving the system. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2000, 57 (Suppl. 4), S10–S17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bifftu, B.B.; Dachew, B.A.; Tiruneh, B.T.; Beshah, D.T. Medication administration error reporting and associated factors among nurses working at the university of gondar referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2015. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, E.M.; Lee, W.K.; Sararaks, S.; Abdul Samad, A.; Liew, S.M.; Cheong, A.T.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Su, S.H.; Mohd Hanafiah, A.N.; Maskon, K.; et al. Medical errors in primary care clinics—A cross sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2012, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Reporting and Learning Systems for Medication Errors: The Role of Pharmacovigilance Centres; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salmasi, S.; Khan, T.M.; Hong, Y.H.; Ming, L.C.; Wong, T.W. Medication errors in the Southeast Asian Countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.H.; Ma, S.M. Willingness of nurses to report medication administration errors in Southern Taiwan: A cross-sectional survey. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2009, 6, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, H.; Shamsuddin, F.; Idris, N.; Hussin, A. Medication errors among nurses in government hospital. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, D.C.; Ibrahim, N.S.; Ibrahim, M.I.M. Medication errors among geriatrics at the outpatient pharmacy in a teaching hospital in Kelantan. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2004, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chua, S.S.; Tea, M.H.; Rahman, M.H.A. An observational study of drug administration errors in a Malaysian hospital (study of drug administration errors). J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009, 34, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samsiah, A.; Othman, N.; Jamshed, S.; Hassali, M.A.; Wan-Mohaina, W.M. Medication errors reported to the national medication error reporting system in Malaysia: A 4-year retrospective review (2009 to 2012). Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisby, M.; Nielsen, L.P.; Mainz, J. Errors in the medication process: Frequency, type, and potential clinical consequences. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2005, 17, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarvadikar, A.; Prescott, G.; Williams, D. Attitudes to reporting medication error among differing healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The qualitative research interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brod, M.; Tesler, L.E.; Christensen, T.L. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, N.; Arieli, T. Field research in conflict environments: Methodological challenges and snowball sampling. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyrick, J. What is good qualitative research? A first step towards a comprehensive approach to judging rigour/quality. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, L.A.; Nembhard, I.M.; Bradley, E.H. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009, 119, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, M.J.; Evans, S.M.; Smith, B.J.; Berry, J.G. Attitudes of doctors and nurses towards incident reporting: A qualitative analysis. Med. J. Aust. 2004, 181, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanghera, I.S.; Franklin, B.D.; Dhillon, S. The attitudes and beliefs of healthcare professionals on the causes and reporting of medication errors in a UK intensive care unit. Anaesthesia 2007, 62, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, R.; Carruthers, S.; Gardner, P.; Wright, J.; McEachan, R.R. Identifying the latent failures underpinning medication administration errors: An exploratory study. Health Serv. Res. 2012, 47, 1437–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajornboon, A.B. Using interviews as research instruments. E-J. Res. Teach. 2005, 2. Available online: http://www.culi.chula.ac.th/research/e-journal/bod/annabel.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Burnard, P.; Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuckett, A.G. Qualitative research sampling-the very real complexities. Nurse Res. 2004, 12, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 1999, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.Y.; Min, T.H.; Ming, E.J.C.; Sheng, J.Y.B.; Ahmad, K. Qualitative research on medication safety among nurses and pharmacists in hospital miri. Sarawak J. Pharm. 2015, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, S.M.; Perera, S.; Olshansky, E.F.; Studenski, S.A.; Nace, D.A.; Fridsma, D.B.; Hanlon, J.T. Identifying modifiable barriers to medication error reporting in the nursing home setting. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2007, 8, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkalmi, R. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, Perception and Barriers towards Pharmacovigilance Activities among Community Pharmacists and Final Year Pharmacy Students in Malaysia; Universiti Sains Malaysia: Penang, Malaysia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pharmaceutical Services Division. Guideline on Medication Error Reporting, 1st ed.; Ministry of Health: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2009; p. 30.

- Koohestani, H.R.; Baghcheghi, N. Barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors among nursing students. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 27, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Martowirono, K.; Jansma, J.D.; van Luijk, S.J.; Wagner, C.; Bijnen, A.B. Possible solutions for barriers in incident reporting by residents. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzibanjan, A.; Laaksonen, R.; Weiss, M.; Airaksinen, M.; Wuliji, T. Medication Error Reporting Systems—Lessons Learnt; International Pharmaceutical Federation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/Patient%20Safety/Medication%20Error%20Reporting%20-%20Lessons%20Learnt2008.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Potylycki, M.J.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ritter, M.; Capuano, T.; Gross, L.; Riegel-Gross, K.; Panik, A. Nonpunitive medication error reporting: 3-year findings from one hospital’s primum non nocere initiative. J. Nurs. Adm. 2006, 36, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.M.; Berry, J.G.; Smith, B.J.; Esterman, A.; Selim, P.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; DeWit, M. Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: A collaborative hospital study. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, H.P.; Yu, S.; Chu, C.; Hou, I.C.; Tang, F.I. Nurses’ attitudes and perceived barriers to the reporting of medication administration errors. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covell, C.L.; Ritchie, J.A. Nurses’ responses to medication errors: Suggestions for the development of organizational strategies to improve reporting. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2009, 24, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, M.B.; Abraham, I.; Lindenauer, P.K.; Rose, D.N. Improving nurse-to-patient staffing ratios as a cost-effective safety intervention. Med. Care 2005, 43, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride-Henry, K.; Foureur, M. Medication administration errors: Understanding the issues. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 23, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suresh, G.; Horbar, J.D.; Plsek, P.; Gray, J.; Edwards, W.H.; Shiono, P.H.; Ursprung, R.; Nickerson, J.; Lucey, J.F.; Goldmann, D. Voluntary anonymous reporting of medical errors for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, D.N.; Retrosi, T.; Ostrowski, G. Barriers to medication error reporting among hospital nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filep, B. Interview and translation strategies: Coping with multilingual settings and data. Soc. Geogr. 2009, 4, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Number (n = 23) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 22 | 95.7 |

| Male | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Race | Malay | 22 | 95.7 |

| Chines | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Age | ≤30 | 6 | 26.1 |

| 30–40 | 14 | 60.9 | |

| 41–50 | 2 | 8.7 | |

| 51≥ | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Education level | Diploma | 21 | 91.3 |

| Bachelor | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Experience in years | ≤5 | 5 | 21.7 |

| 6–10 | 6 | 26.1 | |

| ≥11 | 12 | 52.2 | |

| Practice site | Medical unit | 4 | 17.4 |

| ICU a | 9 | 39.1 | |

| CCU b | 2 | 8.7 | |

| A & E c | 3 | 13 | |

| Orthopaedic unit | 2 | 8.7 | |

| NICU d | 1 | 4.3 | |

| Paediatric unit | 2 | 8.7 | |

| Number of reports in the last 12 months | Never report | 18 | 78.3 |

| ≥1 | 5 | 21.7 | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dyab, E.A.; Elkalmi, R.M.; Bux, S.H.; Jamshed, S.Q. Exploration of Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting in a Tertiary Health Care Facility: A Qualitative Approach. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6040120

Dyab EA, Elkalmi RM, Bux SH, Jamshed SQ. Exploration of Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting in a Tertiary Health Care Facility: A Qualitative Approach. Pharmacy. 2018; 6(4):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6040120

Chicago/Turabian StyleDyab, Eman Ali, Ramadan Mohamed Elkalmi, Siti Halimah Bux, and Shazia Qasim Jamshed. 2018. "Exploration of Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting in a Tertiary Health Care Facility: A Qualitative Approach" Pharmacy 6, no. 4: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6040120

APA StyleDyab, E. A., Elkalmi, R. M., Bux, S. H., & Jamshed, S. Q. (2018). Exploration of Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers towards Medication Error Reporting in a Tertiary Health Care Facility: A Qualitative Approach. Pharmacy, 6(4), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6040120