Abstract

Objective: To describe the development of a community pharmacy-based intervention aimed at optimizing experience and use of antidepressants (ADs) for patients with mood and anxiety disorders. Methods: Intervention Mapping (IM) was used for conducting needs assessment, formulating intervention objectives, selecting change methods and practical applications, designing the intervention, and planning intervention implementation. IM is based on a qualitative participatory approach and each step of the intervention development process was conducted through consultations with a pharmacists’ committee. Results: A needs assessment was informed by qualitative and quantitative studies conducted with leaders, pharmacists, and patients. Intervention objectives and change methods were selected to target factors influencing patients’ experience with and use of ADs. The intervention includes four brief consultations between the pharmacist and the patient: (1) provision of information (first AD claim); (2) management of side effects (15 days after first claim); (3) monitoring treatment efficacy (30-day renewal); (4) assessment of treatment persistence (2-month renewal, repeated every 6 months). A detailed implementation plan was also developed. Conclusion: IM provided a systematic and rigorous approach to the development of an intervention directly tied to empirical data on patients’ and pharmacists’ experiences and recommendations. The thorough description of this intervention may facilitate the development of new pharmacy-based interventions or the adaptation of this intervention to other illnesses and settings.

1. Introduction

Mood and Anxiety Disorders (MADs) are the most prevalent mental illnesses in Canada [1]. In 2013, 11.6% of Canadians adults reported having a MAD [2]. MADs have been shown to be associated with chronic illnesses such as respiratory and heart diseases [1]. They also have negative consequences on patients’ social relationships and quality of life, increase the risk of suicide, and represent an important economic burden to society [3,4,5]. Antidepressants (ADs) are recommended by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) for the treatment of MADs, alone or in conjunction with psychotherapy [3,5]. According to the CANMAT guidelines, ADs should be continued for several weeks after full response: 6–24 weeks for depression [3] and 12–24 weeks for anxiety disorders [5,6]. MAD patients report several needs regarding ADs, and a high proportion of patients will end treatment prematurely [7,8,9,10,11].

Several studies have explored factors that negatively influence patients’ experiences with and adherence to ADs. A meta-ethnography conducted among patients with depression showed that patients constantly re-evaluate the relevance of antidepressant drug treatment and reassess their willingness to continue treatment [12]. Adverse effects [13,14], lack of support from the prescribing physician [14,15], lack of confidence in the efficacy of ADs [16], holding a negative opinion of ADs [12,13,17,18], and being strongly affected by the social stigma associated with the diagnosis of a mental health problem [16,19] appeared to negatively influence AD adherence and patients’ experiences with treatment. In a literature review [11], poor instruction about ADs, lack of follow-up from the prescribing clinician, patients’ fear of addiction, low motivation, lower depression severity, and a complex drug regimen were also associated with nonadherence in some studies.

Community pharmacists can play a pivotal role in addressing issues faced by patients prescribed ADs for MADs [20]. Community pharmacists have frequent interactions with these patients and some previous community pharmacy-based interventions conducted among patients with depression [21] or common mental illnesses (primarily anxiety or depression) [22] reported promising results for improving patients’ adherence to ADs. Findings from a systematic review [21] and meta-analyses of controlled trials reported significant effects on AD adherence (odds ratio of 2.5) for interventions delivered by pharmacists in outpatient clinics or community pharmacies but reported non-significant effects on the reduction of clinical symptoms [23]. Some of these reviews concluded that better results could be expected for adherence and reduction of clinical symptoms in better-designed interventions. Indeed, although interventions included patient education [22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], monitoring symptoms [24,25,26,27,28,29], and management of side effects [27,32], they mainly targeted one phase of AD adherence (initiation or maintenance) and most studies failed to provide a detailed description of the intervention content or the anticipated change process and did not control for the extent to which the intervention was implemented. All of these factors may have lowered the potential effects of the intervention. In addition, to the best of our knowledge, only one of these interventions was designed using behavior change theories and a structured approach to intervention development [22].

Intervention Mapping (IM) [33] is a step-by-step protocol that assists planners in developing complex health promotion interventions [34]. Each step of the intervention development is based on a qualitative participatory approach involving consultations with relevant stakeholders to elucidate the challenges and facilitating factors that may affect the success of the intervention [33]. Previous reviews of controlled studies report that interventions based on IM showed significant results on health promotion behaviors [35] and on the adoption of innovative health care practices [36]. More specifically, earlier studies have demonstrated that interventions based on IM significantly improved medication adherence for antiretroviral therapy [37] and drug treatment for depression and anxiety [22], among others. This highlights the relevance of using the IM process for designing interventions with potential for efficacy [33,38].

The aim of the present paper is to present the Intervention Mapping process that was followed for the development of a community pharmacy-based intervention aimed at optimizing the use of ADs for patients with MADs as well as their experience with the treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The current study was carried out in the province of Quebec, Canada. As recommended by the developers of the IM protocol [33], a qualitative participatory approach was used to construct and develop the intervention [39]. This involved collaboration between researchers and community pharmacists in order to share knowledge and develop actions that take into account the perspectives of different actors, and it took the form of a pharmacists’ committee that was involved in each step of the process. This committee consisted of four community pharmacists. The size of this group was judged appropriate to facilitate discussions as, prior to meetings with this pharmacists’ committee, we also gained important input on the role of community pharmacists for patients taking ADs by conducting one quantitative and three qualitative studies [40,41,42,43]. Committee members were identified through the contacts of the research group. To be included in the committee, members had to (1) be currently working as a community pharmacist, or to have worked as a community pharmacist and be currently involved in training pharmacy students; and (2) be available for and willing to participate in the intervention development meetings. The pharmacists’ committee included two men and two women. Committee members were all more than 40 years old and had extensive experience in community pharmacy (with pharmacy degrees obtained more than 15 years ago) as owners or salaried employees. Some of them knew each other prior to the establishment of the committee. Only one member reported significant previous experience in developing an intervention to improve medication adherence. As committee members were more familiar with the practices of community pharmacists than the research and intervention development processes, they were very conscious of the feasibility and the operational aspects of the intervention under development. Meetings with the committee were conducted to develop an understanding of pharmacists’ points of view, provide opportunities for sharing experiences, and to make decisions and integrate these decisions into a concrete intervention plan. The committee was facilitated by one expert in IM (HG) and two researchers (patient health education, LG; epidemiology, SL). One researcher (LG) was trained in cognitive behavioral approaches and more specifically in behavior change theories. One researcher (SL) was trained in social and cultural anthropology and epidemiology with an expertise in medication use research. This influenced the decisions made throughout the intervention development process, such as the selection of theoretical methods and practical applications as well as the concrete development of the intervention design. The facilitators’ roles were to provide the documentation necessary to support the reflective process prior to meetings and to facilitate the meeting discussions. Concretely, each meeting was devoted to one of the six steps of the IM protocol. At the beginning of each meeting, the facilitators presented the tasks associated with the step and provided the documentation needed to carry out the tasks. Occasionally, the facilitators supplied suggestions or a first draft as a basis for discussion. The number of meetings was not defined a priori and was dependent on the time necessary to complete the development of the intervention.

2.2. The Intervention Mapping Protocol for Designing Interventions

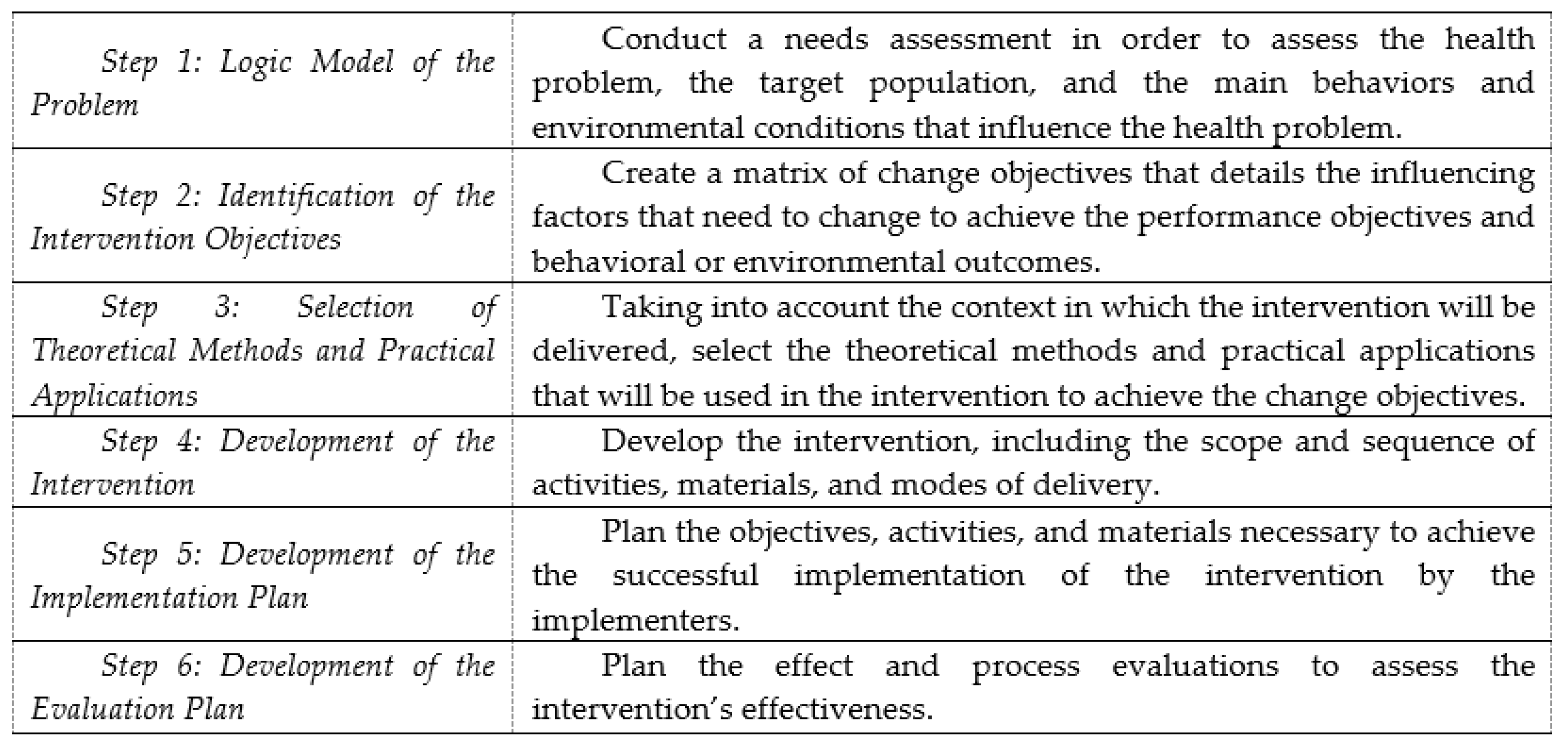

The step-by-step process of IM allows the development of health promotion interventions based on theories, scientific literature, and data collected in the field [33,38]. It comprises six fundamental steps that build on each other. Although IM is presented as a series of steps, the planning process is iterative rather than linear [33,38]. Each step is conducted in partnership with a steering committee composed of relevant stakeholders. The use of a participatory approach for the development of the intervention is at the core of the Intervention Mapping process. Figure 1 depicts these steps.

Figure 1.

Intervention Mapping protocol steps.

Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem. In IM [33], the development of an intervention should be preceded by a needs assessment in order to assess the health problem, the target population, the main behaviors and environmental conditions that influence the health problem, the main factors that influence these behaviors and environmental conditions, and the characteristics of previous interventions for a similar issue. This involves an extensive review of the literature and primary research.

Step 2: Identification of the Intervention Objectives. At this step, measurable behavioral and environmental outcomes are formulated. For some interventions, only behavioral or environmental outcomes may be relevant, while for other interventions, both are important. In the present study, only one behavioral outcome was formulated (e.g., each adult with a new prescription has an optimal experience with and use of ADs) since the achievement of this behavioral outcome was expected to improve the targeted health outcomes. Then, each behavioral outcome is subdivided into performance objectives, which are the logical and procedural steps necessary for the individual to achieve the behavioral outcomes [33] (e.g., the patient verbally commits to a systematic follow-up plan with the pharmacist). On the basis of the needs assessment, the factors influencing each behavioral outcome are linked to relevant performance objectives in a table, thereby creating a matrix of change objectives (e.g., the patient knows that he/she can contact a pharmacist) that details how these influencing factors need to change to achieve the performance objectives and behavioral outcomes.

Step 3: Selection of Theoretical Methods and Practical Applications. To operationalize the change objectives into practical applications that will be used in the concrete intervention, theoretically informed methods are selected, taking into account the context and environment in which the intervention will be delivered. The selection is based on a taxonomy developed by the originators of IM [33], the empirical effectiveness and feasibility of these methods for achieving the behavioral outcomes, and performance objectives in similar populations and settings [44,45,46]. One class of methods in this taxonomy is the “basic methods”, which are likely to influence several factors related to behavioral adoption. Other classes of behavior change methods are specific to a factor influencing behavior adoption (e.g., self-efficacy) and a theory (e.g., social cognitive theory).

Step 4: Development of the Intervention. This step involves the development of the intervention itself, including the scope and sequence of activities, materials, and modes of delivery. The intervention content and materials are determined in relation to the change objectives formulated in Step 2 and the theoretical methods and practical applications selected in Step 3. Finally, the whole intervention is verified to ensure that it meets the characteristics defined in Steps 1, 2, and 3.

Step 5: Development of the Implementation Plan. In a similar manner to what is described in Step 2, a matrix is elaborated for each behavioral outcome (e.g., drug therapy monitoring is systematically implemented) that describes what is needed to achieve the successful implementation of the intervention by the implementers (defined as those with a role in the implementation process). The influencing factors of each behavioral outcome (e.g., knowledge, self-identity) are identified based on the findings of the needs assessment and are linked to performance objectives to create a matrix of change objectives [33]. The change objectives are converted into practical applications based on a range of evidence and the taxonomy developed by Kok et al. [33,38].

Step 6: Development of the Evaluation Plan. Evaluations to assess the effects and processes of the intervention are designed by selecting evaluation objectives and deciding on indicators, their measures, and data collection procedures. Mixed research methods are usually involved in evaluation planning.

3. Results

3.1. Step 1: Logic Model of the Problem

A needs assessment was conducted that included literature reviews on several topics: (1) patients’ use of ADs and associated factors; (2) patients’ experience with ADs and associated factors; and (3) the characteristics, effects, and limits of community pharmacy-based interventions that target patients’ use of and experience with ADs. While patients’ experiences with ADs and the challenges patients face have been extensively documented in the published literature, there was a lack of information on patients’ experiences of pharmacy services and the actual and optimal pharmacy practices for this population. To complete the information collected from these reviews, three descriptive exploratory qualitative studies were conducted: (1) individual interviews with patients prescribed ADs (n = 14) [40]; (2) individual interviews with key informants in mental health and pharmacist practices (n = 21) [41]; and (3) focus groups with community pharmacists (n = 43) [42]. The aims of these studies were the following: (1) to describe community pharmacists’ current practices and challenges; (2) to explore the factors influencing the initiation of ADs and persistence for the whole length of treatment; and (3) the potential contributions of community pharmacists to improve patients’ use of and experience with ADs. Following these qualitative studies, a cross-sectional study was conducted among community pharmacists in the province of Quebec (n = 1609) to identify the psychosocial factors influencing whether pharmacists would deliver four interventions per year to enhance patients’ use of and experience with ADs [43]. The key findings of these studies are presented in Table 1. Findings from this needs assessment were presented and discussed at the first meeting with the pharmacists’ committee.

Table 1.

Synthesis of four studies conducted to assess patients’ and community pharmacists’ needs regarding antidepressant (AD) treatment (Step 1 of the Intervention Mapping protocol).

3.2. Step 2: Identification of the Intervention Objectives

The intervention objectives were formulated collaboratively with the pharmacists’ committee during the second meeting. The behavioral objective of the intervention was “each adult with a MAD who presents with a new prescription for ADs at pharmacy has an optimal experience with and use of ADs.” Six performance objectives were formulated in the following order: (PO1) the patient verbally commits to a systematic pharmaceutical follow-up plan with the pharmacist that includes at least four brief consultations; (PO2) the patient makes an informed decision to initiate ADs; (PO3) the patient takes the ADs as prescribed throughout the treatment period (dosage, time, and frequency); (PO4) the patient copes with the side effects of the treatment; (PO5) the patient assesses the benefits of taking the ADs; and (PO6) the patient makes an informed decision to persist with the treatment throughout the length of the prescription. Change objectives were formulated by crossing performance objectives to the influencing factors identified in Step 1: knowledge, attitude, self-efficacy, and intention (Table 2).

Table 2.

Matrix of objectives (Step 2 of the Intervention Mapping protocol). Behavioral outcome: Each adult with a Mood and Anxiety Disorder (MAD) presenting with a new prescription for ADs at pharmacy has an optimal experience with and use of ADs.

3.3. Step 3: Selection of Theoretical Methods and Practical Applications

In a third meeting with the pharmacists’ committee, theoretical methods and practical applications to change the influencing factors specified in Step 2 were organized into a coherent intervention. Participation, discussion, individualization, belief selection, reinforcement, and anticipation of the adaptation strategies to be employed were chosen (see Kok’s taxonomy for the definitions and associated practical applications) [38]. For example, reinforcement, derived from social cognitive theory [47] was translated into a practical application by pharmacists providing encouragement and rewards to patients. All the selected methods belong to the category of “basic methods” that are defined in IM as being useful for several individual influencing factors, including those identified in our study (e.g., participation may be useful in modifying knowledge, attitude and self-efficacy). The authors of the IM protocol recommend prioritizing these methods as their efficacy has been empirically and extensively demonstrated in interventions at the individual level. In addition, these basic methods were deemed to be the most promising in a context where the intervention is very brief and as likely to increase pharmacists’ adoption of the intervention. The full list of the selected theory-based methods and their translation into a range of practical intervention applications is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Theoretical methods, application parameters and practical applications (Step 3 of the Intervention Mapping protocol).

3.4. Step 4: Development of the Intervention Design

In a fourth meeting with the pharmacists’ committee, the intervention components were selected based on the needs assessment (see details in Step 1). The intervention components were identified based on the change objectives (Step 2). The resultant intervention was to consist of four patient consultations of 3–5 min each: (1) providing information (at initial ADs claim); (2) management of side effects (15 days after first claim); (3) monitoring treatment efficacy (at 30-day renewal); and (4) assessment of treatment persistence (at 2-month renewal). This fourth consultation was to be repeated every 6 months or as needed. The theoretical methods selected in Step 3 (participation, discussion, individualization, belief selection, reinforcement and anticipation of the adaptation strategies to be employed) and their associated practical applications are to be used concomitantly in each of these patient consultations (and not in one patient consultation in particular). These four patient consultations are to be supported by a brief written document that lists the essential information to discuss with the patient, can be used by the pharmacist during a consultation, and can be given to the patient (this document is currently in development). Some patients who discontinue treatment without informing the pharmacist would be identified at a subsequent visit through the pharmacy’s computer system (whatever the medication requested at that visit). However, no proactive procedure such as a telephone follow-up was planned. This was mainly because such follow-up could not realistically be carried out as part of pharmacists’ usual practices. Detailed information on the sequential components of the intervention is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sequence, content, objectives and documents used (Step 4 of the Intervention Mapping protocol).

3.5. Step 5: Development of the Adoption and Implementation Plan

To ensure the implementation of the intervention in community pharmacies, a second matrix targeting community pharmacists was developed. Three performance objectives were identified: (1) pharmacists become familiar with the content of the four consultations comprising the intervention and adopt this systematic drug therapy monitoring intervention; (2) pharmacists make adjustments to their environment to facilitate the implementation of the intervention; (3) the pharmacists and the pharmacy team decide on a specific date for initiating the intervention. Change objectives were formulated by crossing the performance objectives to the factors influencing pharmacists’ intention to provide four consultations monitoring patients’ use of and experience with ADs identified in our cross-sectional study [43]. Detailed information on this matrix of objectives and the associated theoretical methods and applications is provided in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Matrix of objectives for intervention implementation (Step 5 of the Intervention Mapping protocol). Behavioral outcome: A drug therapy monitoring intervention of four brief consultations is systematically implemented for adult patients with MADs presenting with a new prescription for ADs at pharmacy.

Table 6.

Theoretical methods, application parameters, and practical applications for the implementation of the intervention (Step 5 of the Intervention Mapping protocol).

3.6. Step 6: Development of the Evaluation Plan

The research protocol for evaluating the processes and effects of the intervention is currently under development. Objectives will be selected from those formulated (health and behavioral outcomes, performance and change objectives) to guide the effect evaluation; the process evaluation will be based on the parameters for use and the quality of the implementation. A pilot study should first be conducted to refine the intervention before conducting a large-scale study.

4. Discussion

This systematic process based on the IM protocol resulted in a comprehensive intervention built in partnership with community pharmacists; it was based on theoretical models, best available scientific evidence, and empirical data collected among the targeted populations (e.g., patients, community pharmacists, and leaders in pharmacy and mental health). This process is likely to increase the potential efficacy of the intervention thus developed and improve its implementation. This study is one of the few to offer a detailed description of the development process and the theoretical underpinnings of a pharmacy-based intervention designed to improve the use and experience of ADs for patients with MADs. Except for two interventions that were also modeled on IM [55,56], the vast majority of previous community pharmacy-based interventions intending to optimize experience and/or use of drug treatments for patients with mental illnesses did not seem to have been developed using a structured approach in terms of intervention development and behavior change theories.

During the development process, several benefits to using IM were observed. First, IM provided a systematic step-by-step approach to develop the intervention. IM offered a clear set of tasks to sequentially guide and focus the meetings with the pharmacists’ committee through different questions and decisions regarding the intervention development [34]. Second, IM provided a robust methodology to concretely integrate the results of the original qualitative and quantitative studies, carried out as needs assessment, into the intervention development process [40,41,42,43]. The results from these studies provided the researchers and pharmacists’ committee with a deep understanding of the challenges and incentives that may influence both pharmacists’ practices and patients’ experience with and use of ADs. It should be acknowledged that such extensive preliminary work is not always performed prior to intervention development meetings. In such cases, a greater number of participants and committee meetings are recommended for the development of the intervention. Third, the IM approach provided a template for reflecting and deciding on the extent and the exact modalities of community pharmacists’ involvement in the intervention [36]. IM guided the identification of key leverage points and provided useful checks and balances throughout the intervention development process [57]. The intent was to improve the effectiveness and relevance of the intervention from the perspective of patients, community pharmacists, and the population of Quebec [33]. Fourth, IM enabled the thorough description of this pharmacy-based intervention and of the rationale underlying the decisions. Such descriptions will facilitate the replication and analysis of this intervention in future studies and reviews [58]. It may also support the development of new pharmacy-based interventions or the adaptation of this intervention to other illnesses and settings.

Nevertheless, the limitations related to the use of the IM process should be highlighted. Mainly, the needs assessment and the intervention development process were time-consuming. This challenge has been reported in a previous study that used IM to improve medication adherence [57]. Since researchers, patients, pharmacists, and leaders in pharmacy and mental health may hold different perspectives, a significant amount of work was necessary to incorporate these different views and priorities into a concrete intervention. In addition, the iterative process inherent in intervention development may lead to multiple revisions of the intervention prior to obtaining a consensual version.

5. Conclusions

This paper described the systematic development of a community pharmacy-based intervention aimed at optimizing the use of and experience with ADs for patients with MADs. It was based on the IM protocol, which involves a step-by-step process and a qualitative participatory approach. Through this approach, IM offered a transparent, problem-solving procedure to address the needs of patients prescribed ADs and the challenges of community pharmacists’ practice; it makes use of theory, research evidence, and the perspectives of patients, community pharmacists, and leaders in pharmacy and mental health. The next phases of the research will involve conducting a pilot study to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of this intervention and a larger-scale study to evaluate the processes and impacts of the intervention. The planning process used was based on a robust methodology and resulted in a thorough description of the pharmacy-based intervention. This should facilitate its evaluation, replication, and adaptation to other illnesses or settings.

Author Contributions

S.L. and L.G. led the intervention mapping process and managed the design of the current intervention. T.S. wrote the manuscript. H.G. and D.V. provided comments for each step of the study and reviewed the manuscript. J.M. and J-P.G contributed to the design of the study and needs assessment. All authors approved the submitted version for publication. All authors declare that they had complete access to the study data that support the publication.

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Prends soin de toi (Take care of yourself) program (AstraZeneca, Lilly, Lundbeck and Merck). L. Guillaumie received a post-doctoral research scholarship from the Chair on Adherence to Treatments. The Chair on Adherence to Treatments was funded through unrestricted grants from AstraZeneca Canada, Merck Canada, Pfizer Canada, Sanofi Canada, and the Prends soin de toi program. At time of the study, S. Lauzier was a research scholar with funding from the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (Quebec Health Research Fund) in partnership with the Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (National Institute for Excellence in Health and Social Services).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the pharmacists who participated to the committee: Marie-Claude Boivin, Daniel Kirouac, Brigitte Laforest and Denis Villeneuve.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare that there is no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Report from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Canada; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015; p. 40.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Canada. Fast Facts from the 2014 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014.

- Lam, R.W.; McIntosh, D.; Wang, J.; Enns, M.W.; Kolivakis, T.; Michalak, E.E.; Sareen, J.; Song, W.Y.; Kennedy, S.H.; MacQueen, G.M.; et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 1. Disease burden and principles of care. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, R.W.; Kennedy, S.H.; Parikh, S.V.; MacQueen, G.M.; Milev, R.V.; Ravindran, A.V.; Group, C.D.W. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Introduction and methods. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzman, M.A.; Bleau, P.; Blier, P.; Chokka, P.; Kjernisted, K.; Van Ameringen, M.; Canadian Anxiety Guidelines Initiative Group on behalf of the Anxiety Disorders Association of Canada/Association Canadienne des Troubles Anxieux; McGill, U.; Antony, M.M.; Bouchard, S.; et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14 (Suppl. 1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Lam, R.W.; McIntyre, R.S.; Tourjman, S.V.; Bhat, V.; Blier, P.; Hasnain, M.; Jollant, F.; Levitt, A.J.; MacQueen, G.M.; et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, L.; Fontenelle, L.F. A review of studies concerning treatment adherence of patients with anxiety disorders. Patient Preference Adherence 2011, 5, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bull, S.A.; Hunkeler, E.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Rowland, C.R.; Williamson, T.E.; Schwab, J.R.; Hurt, S.W. Discontinuing or switching selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Ann. Pharmacother. 2002, 36, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, C.D.; Shaya, F.T.; Meng, F.; Wang, J.; Harrison, D. Persistence, switching, and discontinuation rates among patients receiving sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopram. Pharmacotherapy 2005, 25, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, M.; Marcus, S.C.; Tedeschi, M.; Wan, G.J. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the united states. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. Antidepressant adherence: Are patients taking their medications? Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malpass, A.; Shaw, A.; Sharp, D.; Walter, F.; Feder, G.; Ridd, M.; Kessler, D. “Medication career” or “moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Servellen, G.; Heise, B.A.; Ellis, R. Factors associated with antidepressant medication adherence and adherence-enhancement programmes: A systematic literature review. Ment. Health Fam. Med. 2011, 8, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Roy, T. Patient experiences of taking antidepressants for depression: A secondary qualitative analysis. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013, 9, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.; McCabe, R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivin, K.; Kales, H.C. Adherence to depression treatment in older adults. Drugs Aging 2008, 25, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Geffen, E.C.; Hermsen, J.H.; Heerdink, E.R.; Egberts, A.C.; Verbeek-Heida, P.M.; van Hulten, R. The decision to continue or discontinue treatment: Experiences and beliefs of users of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in the initial months: A qualitative study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2011, 7, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.C.; Jacob, S.A.; Tangiisuran, B. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antidepressants among outpatients with major depressive disorder: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirey, J.A.; Bruce, M.L.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Perlick, D.A.; Friedman, S.J.; Meyers, B.S. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001, 52, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Valera, M.; Chen, T.F.; O’Reilly, C.L. New roles for pharmacists in community mental health care: A narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 10967–10990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jumah, K.A.; Qureshi, N.A. Impact of pharmacist interventions on patients’ adherence to antidepressants and patient-reported outcomes: A systematic review. Patient Preference Adherence 2012, 6, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMillan, S.S.; Kelly, F.; Hattingh, H.L.; Fowler, J.L.; Mihala, G.; Wheeler, A.J. The impact of a person-centred community pharmacy mental health medication support service on consumer outcomes. J. Ment. Health 2017, 27, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readdean, K.C.; Heuer, A.J.; Scott Parrott, J. Effect of pharmacist intervention on improving antidepressant medication adherence and depression symptomology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickles, N.M.; Svarstad, B.L.; Statz-Paynter, J.L.; Taylor, L.V.; Kobak, K.A. Pharmacist telemonitoring of antidepressant use: Effects on pharmacist–patient collaboration. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2005, 45, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, D.A.; Bungay, K.M.; Wilson, I.B.; Pei, Y.; Supran, S.; Peckham, E.; Cynn, D.J.; Rogers, W.H. The impact of a pharmacist intervention on 6-month outcomes in depressed primary care patients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capoccia, K.L.; Boudreau, D.M.; Blough, D.K.; Ellsworth, A.J.; Clark, D.R.; Stevens, N.G.; Katon, W.J.; Sullivan, S.D. Randomized trial of pharmacist interventions to improve depression care and outcomes in primary care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2004, 61, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finley, P.R.; Rens, H.R.; Pont, J.T.; Gess, S.L.; Louie, C.; Bull, S.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Bero, L.A. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2003, 23, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, O.H.; van Hout, H.; Stalman, W.; Nieuwenhuyse, H.; Bakker, B.; Heerdink, E.; de Haan, M. A pharmacy-based coaching program to improve adherence to antidepressant treatment among primary care patients. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005, 56, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, J.; Taylor, S.; Grabham, A.; Stanford, P. Patient outcomes following an intervention involving community pharmacists in the management of depression. Aust. J. Rural Health 2006, 14, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosmans, J.E.; Brook, O.H.; van Hout, H.P.; de Bruijne, M.C.; Nieuwenhuyse, H.; Bouter, L.M.; Stalman, W.A.; van Tulder, M.W. Cost effectiveness of a pharmacy-based coaching programme to improve adherence to antidepressants. Pharmacoeconomics 2007, 25, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saffar, N.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Carter, P.; Adib, S.M. Effect of information leaflets and counselling on antidepressant adherence: Open randomised controlled trial in a psychiatric hospital in kuwait. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2005, 13, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, P.R.; Rens, H.R.; Pont, J.T.; Gess, S.L.; Louie, C.; Bull, S.A.; Bero, L.A. Impact of a collaborative pharmacy practice model on the treatment of depression in primary care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2002, 59, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, E.L.K.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Fernandez, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs. An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sabater-Hernandez, D.; Moullin, J.C.; Hossain, L.N.; Durks, D.; Franco-Trigo, L.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Martinez-Martinez, F.; Saez-Benito, L.; de la Sierra, A.; Benrimoj, S.I. Intervention mapping for developing pharmacy-based services and health programs: A theoretical approach. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garba, R.M.; Gadanya, M.A. The role of intervention mapping in designing disease prevention interventions: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durks, D.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Hossain, L.N.; Franco-Trigo, L.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Sabater-Hernandez, D. Use of intervention mapping to enhance health care professional practice: A systematic review. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, M.; Hospers, H.J.; van Breukelen, G.J.; Kok, G.; Koevoets, W.M.; Prins, J.M. Electronic monitoring-based counseling to enhance adherence among HIV-infected patients: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2010, 29, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, G.; Gottlieb, N.H.; Peters, G.J.; Mullen, P.D.; Parcel, G.S.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernandez, M.E.; Markham, C.; Bartholomew, L.K. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: An intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higginbottom, G.; Liamputtong, P. What is participatory research? Why do it? In Participatory Qualitative Research Methodologies in Health; Higginbottom, G., Liamputtong, P., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumie, L.; Ndayizigiye, A.; Beaucage, C.; Moisan, J.; Grégoire, J.-P.; Villeneuve, D.; Lauzier, S. Patient perspectives on the role of community pharmacists for antidepressant treatment: A qualitative study. Can. Pharm. J. 2018, 171516351875581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaumie, L.; Moisan, J.; Gregoire, J.P.; Villeneuve, D.; Beaucage, C.; Bordeleau, L.; Lauzier, S. Contributions of community pharmacists to patients on antidepressants-a qualitative study among key informants. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaumie, L.; Moisan, J.; Gregoire, J.P.; Villeneuve, D.; Beaucage, C.; Bujold, M.; Lauzier, S. Perspective of community pharmacists on their practice with patients who have an antidepressant drug treatment: Findings from a focus group study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2015, 11, e43–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauzier, S.; Guillaumie, L.; Humphries, B.; Moisan, J.; Grégoire, J.P.; Beaucage, C. Psychosocial factors associated with community pharmacists monitoring patients’ use and experience with antidepressant treatments: A cross-sectionnal study using the theory of planned behaviour. 2018; Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrin, V.; Sinclair, V.G.; Gardner, V. Theoretical approaches to enhancing motivation for adherence to antidepressant medications. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, D.E.; Hughes, C.M.; Cadogan, C.A.; Ryan, C.A. Theory-based interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults prescribed polypharmacy: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2017, 34, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljumah, K. Impact of pharmacist intervention using shared decision making on adherence and measurable depressed patient outcomes. Value Health 2016, 19, A19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Barden, J.; Wheeler, S.C. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion: Developing health promotions for sustained behavioral change. In Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research, 2nd ed.; DiClemente, R.J., Crosby, R.A., Kegle, M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Redding, C.A.; Evers, K.E. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt, G.A.; Donovan, D.M. Relapse Prevention; Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. Eur. Psychiatry 2007, 12, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, L.A. Medication Adherence in Bipolar Disorder: Understanding Patients’ Perspectives to Inform Intervention Development; London’s Global University: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, A.; Fowler, J.; Hattingh, L. Using an intervention mapping framework to develop an online mental health continuing education program for pharmacy staff. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2013, 33, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyne, J.M.; Fischer, E.P.; Gilmore, L.; McSweeney, J.C.; Stewart, K.E.; Mittal, D.; Bost, J.E.; Valenstein, M. Development of a patient-centered antipsychotic medication adherence intervention. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).