1. Introduction

Pharmacies are highly accessible health facilities where not only medications but also professional counsel and health promotion are provided by pharmacists. Pharmacists are highly trusted by the public and possess extensive knowledge of pharmacotherapy, human physiology, and disease prevention [

1,

2]. In Poland and other countries, where primary care physicians may be less available, pharmacists now undertake responsibilities like patient education and preventive care [

3,

4].

This enlarging role of the pharmacist is in harmony with global health strategies to extend access to and quality of prevention services outside the normal clinical setting [

5,

6]. Pharmacists are ideally positioned to deliver such services due to their regular contact with the community, professional credibility, and proficiency in both the pharmacological and lifestyle sides of healthcare.

In Poland, public health outreach efforts to more actively incorporate pharmacists are being promoted by legislative reforms and the broadening mission of pharmaceutical care [

7]. The changes hold out the promise of new roles for pharmacists as frontline health advisors and educators, particularly in underserved communities.

Women’s health remains a continuing public health issue. Preventive screening such as Pap smears, HPV testing, and mammograms is recommended but low in uptake, particularly among less educated women or women with lower socioeconomic status [

8,

9]. Young women, on the other hand, face mounting lifestyle-related risks of alcohol consumption, smoking, and physical inactivity [

10]. Due to these problems, health education according to women’s needs should be implemented [

11,

12].

Written educational materials, such as leaflets and brochures, have been used in healthcare for decades to help patients learn and manage their health. Since the 1970s, many studies have looked at how these materials improve patients’ understanding of diseases, treatments, and preventive measures for various conditions, from acute infections to chronic and cardiovascular diseases [

13,

14,

15].

Systematic reviews have consistently shown that educational leaflets can improve patient knowledge, understanding and satisfaction in the short term, particularly when the materials are clearly written and tailored to the target group [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, evidence on long-term retention and sustained behavior change remains inconsistent and is highly dependent on content quality, readability, health literacy, and contextual factors [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Recent reviews indicate that poorly designed educational materials often have limited effectiveness, particularly among individuals with low health literacy [

18,

21]. Unlike many previous studies focusing solely on short-term knowledge outcomes of generic patient information materials, the present study evaluates a pharmacist-developed leaflet within the real-world context of community pharmacy practice, combining knowledge assessment with users’ perceived usefulness and clarity [

15,

16].

In recent years, there has been growing attention on using plain language, effective visual design, and a focus on users when creating written materials. This is particularly important for addressing misinformation and reducing health disparities. Still, there is limited evidence regarding educational leaflets developed by pharmacists and their evaluation in community pharmacy settings, especially in women’s health [

17,

18].

Educational products dispensed by pharmacists, in the form of leaflets, can be good tools for health awareness and encouraging healthy behaviors [

20]. The efficacy of such materials and their impact on women’s knowledge were to be determined by the current study. The aim of this study was to evaluate the immediate impact of a pharmacist-developed educational leaflet on women’s health knowledge and its perceived usefulness, clarity, and acceptability.

2. Materials and Methods

Between September and December 2024, an internet-based survey was distributed to adult women aged 18 years and older residing in Poland. The survey was conducted in three parts: a pre-intervention knowledge test, reading the educational leaflet, and a post-intervention knowledge test. To assess the clarity and comprehensibility of the educational leaflet and survey questions, a pilot test was conducted with 10 women prior to the main study. Feedback from the pilot was used to refine the wording and layout of the materials. Data collected during the pilot phase were not included in the final analysis.

The patient education leaflet was developed in 2024 in the Department of Practical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Care at Poznan University of Medical Sciences within the framework of the academic project of patient education under pharmacists’ supervision. The educational leaflet was developed by a team of pharmacists, including community pharmacists with direct patient-care experience and academic pharmacists involved in pharmacy education and research. It was intended to provide understandable, evidence-based information for the benefit of women’s health literacy and preventive behavior.

The development followed a standard process: (1) topic choice from the most common questions pharmacists are asked in community practice (contraception, pregnancy testing, medication safety, and STI prevention); (2) preparation of draft text following WHO and CDC health literacy guidelines [

24,

25,

26]; (3) review by experts for clinical accuracy and plain language use; and (4) professional graphic design in a tri-fold A4 format (two-sided, full-color) with icons, pictograms, and short sections emphasizing key messages.

The leaflet design included bold headers, bullet-pointed advice, and infographic summaries for each topic. Visual coherence (blue–pink color scheme, sans-serif typeface, high-contrast text) was maintained to optimize readability and beauty.

The educational leaflet consisted of four main sections:

- (1)

Hormonal contraception and its correct use,

- (2)

Safe medication use during pregnancy and breastfeeding,

- (3)

Basics of pregnancy testing and interpretation of results,

- (4)

Prevention and home-testing of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Each section included short text, infographics, and QR codes connecting to reliable sources of medical information.

The educational pamphlet utilized in this study is presented in the

Supplementary Materials (File S1). It was the core intervention medium to improve women’s knowledge on health and was distributed digitally during the survey. The content and visual presentation were maximized for readability and interest according to plain-language and health communication principles.

To ensure the consistency and conciseness of the educational leaflet, its creation process involved consultation with formulators of health communication and pharmacists. The language was rendered simple to read, adhering to plain language guidelines, and presentation featured illustrations and bolded terms for ease of reading. Participants were recruited via online health discussion forums, women’s social media sites, and newsletters circulated within networks of pharmacies. An educational leaflet was digitally distributed as part of the online survey, and participants completed a pretest, read the leaflet, and completed a posttest during the same survey session. No in-person recruitment or direct pharmacist–patient interaction was conducted. Although the leaflet was designed for both digital and printed use in community pharmacy settings, in this study it was delivered exclusively in digital form as part of the online survey.

The post-intervention knowledge test was completed immediately after reading the educational leaflet during the same survey session. The knowledge test consisted of five questions covering four focus areas: hormonal contraception (one question), pregnancy testing (two questions), sexually transmitted infection (STI) self-testing (one question), and medication safety during pregnancy (one question). The same set of questions was used in both the pre- and post-intervention assessments. Objective knowledge was measured using a test, while perceived knowledge was assessed using self-assessment questions. Each knowledge question was scored dichotomously. A correct answer was awarded 1 point. Incorrect answers, unanswered questions, partially correct answers, and “I don’t know” responses were scored 0 points. Each participant’s overall knowledge score was calculated by summing the correct answers to all five questions, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 5. Knowledge scores were analyzed both at the individual question level and based on the total knowledge score. The original knowledge test is available in the

Supplementary Materials (File S2).

The respondents also completed a satisfaction questionnaire assessing the visual appeal, clarity, usability, and interest of the leaflet. This was a 15-item Likert-type questionnaire with some open-ended questions where respondents could leave spontaneous remarks about the aesthetics, clarity, tone, and perceived usefulness of the leaflet. Demographic data including level of education, age, and residential area (urban or rural) were collected to enable comparison of subgroup findings. The questionnaire consisted primarily of closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions were limited to optional comments regarding proposed changes to the leaflet and additional comments. Responses to these open-ended questions were analyzed using a descriptive qualitative approach, where comments were manually reviewed and grouped into broad thematic categories reflecting recurring suggestions or observations. The qualitative component was exploratory in nature and intended solely to complement the quantitative results. The original satisfaction survey questionnaire is provided in the

Supplementary Materials (File S3).

STATISTICA 12 and STATA 14 were utilized for data analysis. Statistical tests included chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis tests, and the significance level of α = 0.05 was defined.

Each respondent voluntarily consented to participate before participating in the study. The work was approved by the bioethics committee no. 579/24 at the Poznan University of Medical Sciences.

4. Discussion

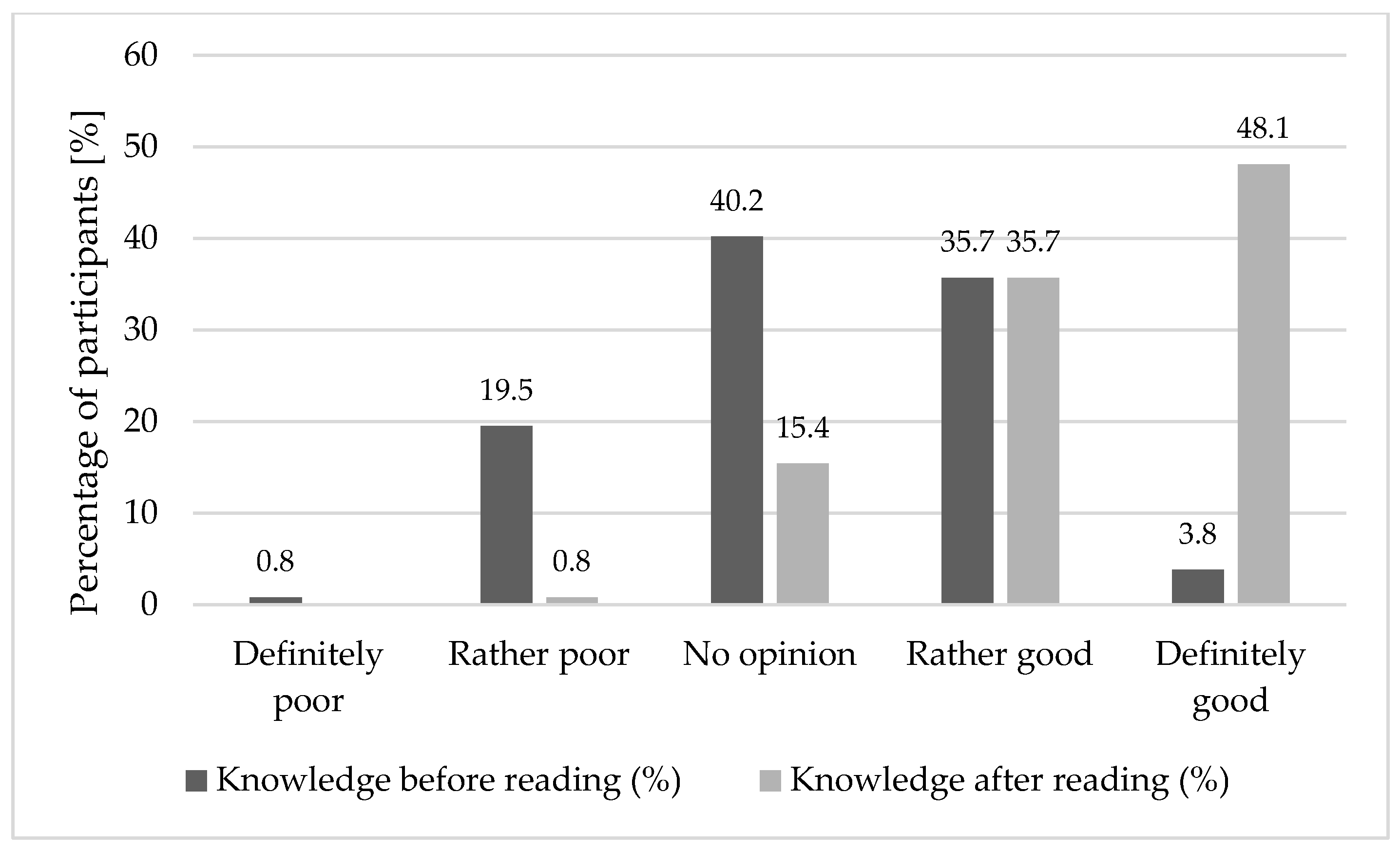

This study supports the impact that educational materials developed by pharmacists can have on increasing women’s knowledge about reproductive health. The most significant impact was seen in those who had the lowest pre-interventional knowledge, as seen in other research on the effectiveness of plain-language materials [

1,

12]. Although the study assesses immediate post-intervention outcomes, its contribution lies in demonstrating how pharmacist-designed written materials can function as a practical, acceptable, and scalable educational tool in community pharmacies.

The visual display of the leaflet, structure, and accessibility made comprehension easier, as suggested by WHO and CDC [

24] health communication principles. More importantly, participants who perceived the content as “clear” tended to achieve higher post-test scores, supporting research indicating that perceived clarity is a strong predictor of learning [

6].

Younger participants demonstrated the greatest knowledge improvement and reported higher satisfaction with the leaflet. Results are in accord with overall literature on the value of relevant health information [

11].

Open-ended answers corroborated this. Participants liked or preferred the tone, style, and convenience of accessing materials from pharmacies. These results concur with Kosycarz & Walendowicz’s research proving that personalization and availability increase engagement [

12]. Participants also liked pharmacists as expert, accessible teachers [

2,

4,

5].

Still, inequalities remain. Older women and women with lower educational attainment were less likely to rate the leaflet as easy to understand and tended to assign lower understandability scores. To address these differences, future interventions may benefit from combining written materials with oral counseling and multimedia content to enhance inclusivity and accessibility across diverse populations.

These findings also highlight the importance of transparency and reproducibility in pharmacist-led educational interventions. Transparency regarding the leaflet’s authorship, purpose, and design process is essential for replication. Future studies should publish visual examples or standardized templates to facilitate methodological reproducibility and cross-country comparison of pharmacist-led health education materials.

One notable finding was the impact of a single leaflet. Over 60% of women rated it as “definitely useful,” suggesting that even brief targeted education campaigns in pharmacies can contribute to public health. Earlier national policies suggest extending the role of pharmacists in prevention, especially among disadvantaged groups [

3,

7]. In the context of misinformation and declining screening rates [

8,

9], materials designed for use in community pharmacy settings may offer a less expensive, scalable, and consistent way.

In the broader public health context, the effectiveness of a single, well-designed educational leaflet is particularly noteworthy given the current challenges of misinformation, time constraints in healthcare, and declining participation in preventive programs. Women increasingly rely on informal or online sources of health information, which can be incomplete, inaccurate, or contradictory [

27]. Community pharmacies, as trusted and easily accessible healthcare providers, can therefore play a key role in countering misinformation by offering concise, evidence-based educational materials that align with national and international recommendations [

28].

Importantly, printed materials distributed through pharmacies can reach people who do not regularly utilize other parts of the healthcare system. This includes women who delay preventive screenings, avoid healthcare facilities due to anxiety or logistical barriers, or perceive their health problems as insufficiently serious to warrant a doctor’s visit [

29]. In such contexts, educational leaflets can serve as a low-threshold intervention, raising awareness and prompting reflection on health behaviors without the need for immediate consultation with a physician [

30].

The positive reception of the leaflet observed in this study supports the feasibility of incorporating similar materials into daily pharmacy practice. Even brief exposure to targeted educational content can contribute to improved awareness and preparedness for future health decision-making, especially when reinforced through repeated meetings or follow-up counseling.

In addition to the increased knowledge observed in this study, the results have a number of practical implications for community pharmacy practice and the broader organization of women’s health education. Community pharmacies are one of the most frequently visited points of contact with the healthcare system, often serving individuals who do not regularly use primary care or specialist consultations. Consequently, pharmacies provide low-threshold and easily accessible venues for health promotion, education, and preventive interventions, as demonstrated by recent analyses of the expanded role of community pharmacies in primary care systems [

31].

Educational leaflets developed by pharmacists can complement existing healthcare services by answering common patient questions in a structured and evidence-based manner. Previous studies have shown that educational interventions delivered by pharmacists in community pharmacies can improve patient knowledge, medication safety, and health decision-making [

32,

33]. Written materials can further standardize the quality of information provided, ensuring adherence to clinical recommendations and reducing the variability associated with informal or ad hoc counseling, particularly in areas such as reproductive health, self-diagnosis, and medication use [

32].

Integrating pharmacist-created educational materials into routine pharmacy workflows can also promote time-efficient interactions with patients. Given the increasing workload and time pressures in community pharmacies, written materials can serve as an extension of oral counseling, allowing patients to review information at their own pace and revisit key messages after the encounter [

33]. This approach can be particularly valuable for sensitive or stigmatized topics, where patients may be reluctant to initiate discussion or may benefit from private reflection. From a healthcare systems perspective, the use of standardized educational materials in community pharmacies can contribute to improving health literacy at the population level. Systematic review evidence suggests that community pharmacists play a vital role in preventive care and chronic disease management through patient education and counseling, supporting broader public health goals. Although this study did not assess behavioral outcomes, a better understanding of health-related issues is widely recognized as essential for making informed health decisions and engaging in preventative care [

34].

Finally, the development and evaluation of pharmacist-led educational tools aligns with ongoing efforts to strengthen the professional role of pharmacists beyond medication dispensing toward more patient-centered and preventative services. Actively engaging pharmacists in the creation and dissemination of educational materials can increase their visibility as credible sources of health information and facilitate closer integration of community pharmacies into multidisciplinary public health strategies [

34,

35].

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the educational leaflet covered a wide range of women’s health topics relevant to different stages of life; therefore, not all sections were equally relevant to all age groups. In particular, content regarding contraception, pregnancy, or breastfeeding may have been less relevant to older participants. However, the primary goal of the study was to assess the clarity, comprehensibility, and perceived usefulness of the educational materials developed by pharmacists, not their individual clinical usefulness.

Second, the study employed a pre–post design with assessments conducted immediately after the intervention, which primarily addresses short-term knowledge acquisition. Although this approach is commonly used in educational research, the improvement in posttest scores may partially reflect exposure to the information rather than sustained understanding. Because the posttest was conducted immediately after reading the leaflet, conclusions regarding long-term knowledge retention or behavior change cannot be drawn.

Third, the study relied on a sample of motivated volunteers recruited online, which may have increased participants’ willingness to engage with the educational content and may limit the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, although pharmacists developed the leaflet, the research team did not include a dedicated clinical expert in women’s health, which may have influenced content prioritization.

Finally, some age subgroups were relatively small, reducing the reliability of subgroup analyses and suggesting that future studies might consider combining smaller categories to increase statistical power.

4.2. Future Research

Overall, the results support the value of pharmacist-created educational leaflets as effective tools for improving short-term knowledge and awareness of women’s health. However, because this study assessed immediate knowledge acquisition, future research should adopt a longitudinal design to assess long-term retention and behavioral outcomes. In particular, studies examining educational materials developed and actively delivered by pharmacists during face-to-face consultations in community pharmacies could provide deeper insights into their actual effectiveness. Furthermore, including surveys assessing participants’ intended actions after viewing the educational materials could help us better understand the mechanisms by which pharmacist-provided education influences preventive behaviors and health decision-making.

5. Conclusions

Educational materials developed by pharmacists for community pharmacy practice may serve as a useful tool for improving women’s health knowledge and may support preventive care through short-term knowledge enhancement. Clear, interesting, and scientifically accurate leaflets work well with patients and promote awareness. Pharmacists need to be reminded to incorporate such material into day-to-day counseling, particularly in community pharmacies where access is common.

As misinformation and health disparities, particularly among women of lower socioeconomic status, rise, precision-crafted interventions based on evidence-based educational resources can equalize access to correct information. Because of their level of exposure and professional standing, pharmacists have to be motivated and empowered further to carry out educational outreach.

Pharmacist-provided educational programs and materials may be a low-cost public health intervention, particularly for countries bearing the burden of the health system or care disparities regions.

From a practical perspective, the results support the role of community pharmacists as key players in women’s health education. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to develop and disseminate evidence-based educational materials that address common patient questions and address knowledge gaps, as highlighted in previous studies on pharmacist-led patient education and pharmaceutical care [

27,

28]. Although this study assessed the leaflet as a standalone educational tool, incorporating such materials into routine pharmacy consultations could further enhance their impact.