How Have Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) Been Implemented in Pharmacy Education? A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

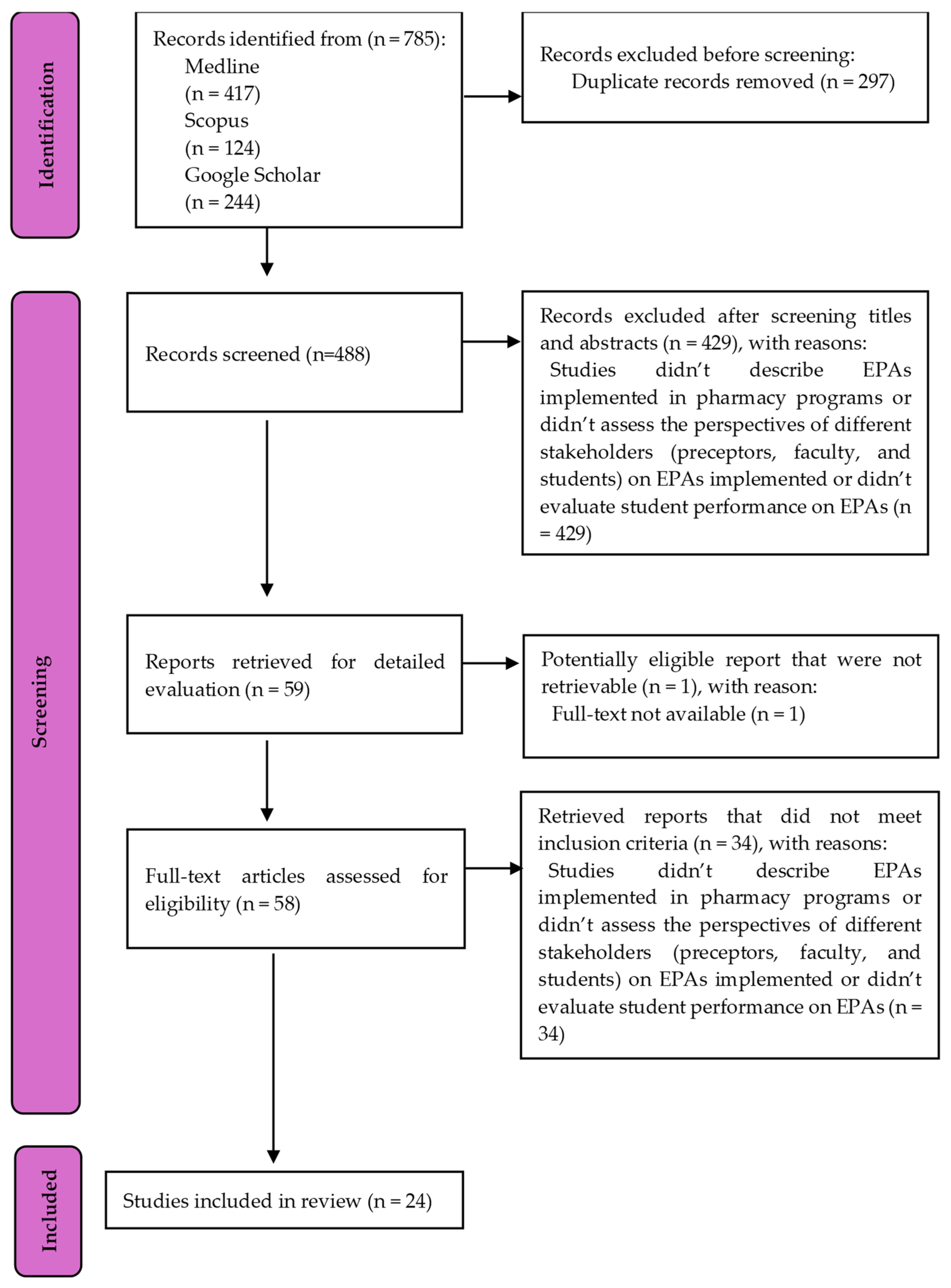

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Use of EPAs in Teaching and Learning

3.2. Facilitators, Barriers, and Recommendations to Improve the Use of EPAs

3.3. Student Performance on EPAs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koster, A.; Schalekamp, T.; Meijerman, I. Implementation of Competency-Based Pharmacy Education (CBPE). Pharmacy 2017, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Cate, O.; Scheele, F. Competency-based postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad. Med. 2007, 82, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Cate, O. An updated primer on entrustable professional activities (EPAs). Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2019, 43 (Suppl. 1), 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Cate, O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 176–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyaratne, C.; Galbraith, K. Implementation and Evaluation of Entrustable Professional Activities for a Pharmacy Intern Training Program in Australia. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 88, 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, A.L.; McKenna, L. Entrustable professional activities in entry-level health professional education: A scoping review. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.T.; Pittenger, A.L.; Stolte, S.K.; Plaza, C.M.; Gleason, B.L.; Kantorovich, A.; McCollum, M.; Trujillo, J.M.; Copeland, D.A.; Lacroix, M.M.; et al. Core Entrustable Professional Activities for New Pharmacy Graduates. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Key Elements for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (“STANDARDS 2025”); Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.Y.; Lounsbery, J.L.; Schweiss, S.; Pittenger, A.L. Preceptor and resident perceptions of entrustable professional activities for postgraduate pharmacy training. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westein, M.P.D.; de Vries, H.; Floor, A.; Koster, A.S.; Buurma, H. Development of a Postgraduate Community Pharmacist Specialization Program Using CanMEDS Competencies, and Entrustable Professional Activities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyaratne, C.; Vienet, M.; Galbraith, K. Development and Validation of Entrustable Professional Activities for Provisionally Registered (Intern) Pharmacists in Australia. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikubiri, H.; Corré, L.; Johnson, J.L.; Marotti, S. Evaluating a medication history-taking entrustable professional activity and its assessment tool—Survey of a statewide public hospital pharmacy service. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyaratne, C.; Galbraith, K.A. Review of Entrustable Professional Activities in Pharmacy Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 83, ajpe8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, A.L.; Gleason, B.L.; Haines, S.T.; Neely, S.; Medina, M.S. Pharmacy Student Perceptions of the Entrustable Professional Activities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivkin, A.; Rozaklis, L.; Falbaum, S. A Program to Prepare Clinical Pharmacy Faculty Members to Use Entrustable Professional Activities in Experiential Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Stewart, R.; Smith, G.; Anderson, H.G.; Baggarly, S. Developing and Implementing an Entrustable Professional Activity Assessment for Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, L.L.; Kinsey, J.; Nykamp, D.; Momary, K. Evaluating Practice Readiness of Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience Students Using the Core Entrustable Professional Activities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.; Drame, I.; McKoy-Beach, Y.; Adesina, S. A Six-Semester Integrated Pharmacy Practice Course Based on Entrustable Professional Activities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 848017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eudaley, S.T.; Brooks, S.P.; Jones, M.J.; Franks, A.S.; Dabbs, W.S.; Chamberlin, S.M. Evaluation of student-perceived growth in entrustable professional activities after involvement in a transitions-of-care process within an adult medicine advanced pharmacy practice experience. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.N.; Murphy, J.A.; Lengel, A.J.; Cruz, B.D. A level of trust: Exploring entrustable professional activities as a feedback tool in a skills lab. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2023, 15, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, C.; Fowler, M.; Wang, S.; Wong, E.; Ivy, D. Descriptive survey of pharmacy students’ self-evaluation of Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPE) and practice readiness using entrustable professional activities. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 23, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, R.D.; Gratz, M.A.; Marwitz, K.K.; Hanson, K.M.; Isch, J.; Robison, H.D. Development, Validation, and Reliability of a P1 Objective Structured Clinical Examination Assessing the National EPAs. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtaynberg, J.; Rivkin, A.; Rozaklis, L.; Gallipani, A. Multifaceted Strategy That Improves Students’ Achievement of Entrustable Professional Activities Across Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmes-Patel, A.T.; Allen, S.M.; Djuric Kachlic, M.; Schriever, A.E.; Driscoll, T.P.; Tekian, A.; Cheung, J.J.H.; Podsiadlik, E.; Haines, S.T.; Schwartz, A.; et al. Preceptor Perspectives Using Entrustable Professional Activity-Based Assessments During Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 101332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L.; Hamrick, J.; Fetterman, J.; Brooks, K. Preceptors’ perceptions of an entrustable professional activities-based community introductory pharmacy practice experience curriculum. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, E.A.; Dillon, A.J.; Bourland, K.; Rybakov, I.; Cluck, D.B.; Veve, M.P. You’ll have to call the attending: Impact of a longitudinal, “real-time” case-based infectious diseases elective on entrustable professional activities to enhance APPE readiness. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2024, 16, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, J.B.; Elmes-Patel, A.T.; Allen, S.M.; Djuric Kachlic, M.; Schriever, A.E.; Driscoll, T.P.; Tekian, A.; Cheung, J.J.H.; Podsiadlik, E.; Haines, S.T.; et al. Longitudinal Preceptor Assessment of Entrustable Professional Activities Across Introductory and Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, T.A.; Richter, L.M.; Dewey, M.; Vigen, K. Multisite survey of pharmacy student perspectives of the layered learning model and ability to participate in core entrustable professional activities during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, A.P.; Richardson, C.L.; Mundell, A.; Lau, W.M.; Nazar, H. Exploring the role of pharmacy students using entrustable professional activities to complete medication histories and deliver patient counselling services in secondary care. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2021, 4, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbery, J.L.; Von Hoff, B.A.; Chapman, S.A.; Frail, C.K.; Moon, J.Y.; Philbrick, A.M.; Rivers, Z.; Pereira, C. Tracked Patient Encounters During Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences and Skill Self-assessment Using Entrustable Professional Activities. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.A.; Marciniak, M.W.; McLaughlin, J.; Melendez, C.R.; Leadon, K.I.; Pinelli, N.R. Exploratory Analysis of Entrustable Professional Activities as a Performance Measure During Early Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjoquist, L.K.; Bush, A.A.; Marciniak, M.W.; Pinelli, N.R. An Exploration of Preceptor-Provided Written Feedback on Entrustable Professional Activities During Early Practice Experiences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, K.; Crescenzi, A.; Pinelli, N.R. Preceptor perceptions of a redesigned entrustable professional activity (EPA) assessment tool in pharmacy practice experiences. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2023, 15, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, K.; Pinelli, N.R.; Persky, A.M. Redesigned Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA) Assessments Reduce Grade Inflation in the Experiential Setting. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croft, H.; Gilligan, C.; Rasiah, R.; Levett-Jones, T.; Schneider, J. Development and inclusion of an entrustable professional activity (EPA) scale in a simulation-based medicine dispensing assessment. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2020, 12, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Hart, N.L.; Rowe, A.S.; Gatwood, J.; Wheeler, J. Incorporation of a mock pharmacy and therapeutics committee as an entrustable professional activity supporting task. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.C.; Kanbar, R.; Btaiche, I.F.; Mansour, H.; Elkhoury, R.; Aoun, C.; Karaoui, L.R. Entrustable professional activities-based objective structured clinical examinations in a pharmacy curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, A.L.; Copeland, D.A.; Lacroix, M.M.; Masuda, Q.N.; Mbi, P.; Medina, M.S.; Miller, S.M.; Stolte, S.K.; Plaza, C.M. Report of the 2016–17 Academic Affairs Standing Committee: Entrustable Professional Activities Implementation Roadmap. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 81, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmes, A.T.; Schwartz, A.; Tekian, A.; Jarrett, J.B. Evaluating the Quality of the Core Entrustable Professional Activities for New Pharmacy Graduates. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, V.; Frontino, M.; Melissen, P.; Barros, M. Student pharmacist perceptions of community advanced pharmacy practice experiences and the impact on professional development. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida Romani, L.F.; de Morais Martins, U.C.; Lima, M.G. Characteristics and outcomes of practice experiences in community pharmacies: A scoping review. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2025, 17, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Protocol | Notes | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medline (Pubmed) | ((((((((((Education, Pharmacy[Title/Abstract]) OR (Students, Pharmacy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Pharmaceutic*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Pharmaceutical Education[Title/Abstract])) OR (Pharmacy Education[Title/Abstract])) OR (Pharmacy Student[Title/Abstract])) OR (Pharmacy Students[Title/Abstract])) OR (pharmacy[Title/Abstract])) OR (pharmacist[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((((((Implementation[Title/Abstract]) OR (implement*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Evaluation[Title/Abstract])) OR (outcome*[Title/Abstract])) OR (assessment[Title/Abstract])) OR (performance[Title/Abstract])) OR (perspective*[Title/Abstract])) OR (perception*[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((entrustable professional activities[Title/Abstract]) OR (EPA[Title/Abstract])) OR ((entrustable professional activity[Title/Abstract])) | Time-restricted research (2016 to 2025); language (English, Portuguese and Spanish | 8 July 2025 |

| Scopus | “Education, Pharmacy” OR “Students, Pharmacy” OR “Pharmaceutic” OR “Pharmaceutical Education” OR “Pharmacy Education” OR “Pharmacy Student” OR “Pharmacy Students” OR “pharmacy” OR “pharmacist” AND “Implementation” OR “implement” OR “Evaluation” OR “outcome” OR “assessment” OR “performance” OR “perspective” OR “perception” AND “entrustable professional activitie” OR “EPA” OR “entrustable professional activity” | Time-restricted research (2016 to 2025); language (English, Portuguese and Spanish) | 8 July 2025 |

| Google Scholar | Education OR Pharmacy OR Pharmacist “entrustable professional activities” OR “entrustable professional activity” | Search ordered by relevance; time-restricted research (2016 to 2025) | 8 July 2025 |

| Inclusion criteria | Studies that describe EPAs implemented in pharmacy education or assess the perspectives of different stakeholders (preceptors, faculty, and students) on EPAs implemented or evaluate student performance on EPAs Studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages Diverse types of studies, such as experience reports, program descriptions or evaluations, observational studies, experimental or quasi-experimental studies, and qualitative and mixed-methods studies Studies published from 2016 to 2025 |

| Exclusion criteria | Studies about professional development initiatives for pharmacists and pharmacy staff, postgraduate-level experiences, and pre-registration internships for provisionally registered pharmacists Studies that did not describe or assess an actual experience of EPA implementation Studies that assessed perceptions of EPAs not actually implemented Studies that assessed student learning but did not adopt EPAs in evaluations |

| Characteristics | Number of Papers (%) |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | |

| 2019–2021 | 11 (45.8) |

| 2022–2025 | 13 (54.2) |

| Country | |

| USA | 21 (87.5) |

| Australia | 1 (4.2) |

| Lebanon | 1 (4.2) |

| United Kingdom | 1 (4.2) |

| Study design | |

| Quantitative | 17 (70.8) |

| Mixed-methods | 4 (16.7) |

| Qualitative | 2 (8.3) |

| Experience report | 1 (4.2) |

| Variables | Number of Papers (%) |

|---|---|

| EPAs assessed | |

| Core EPAs recommended by the AACP for new pharmacy graduates in the USA | 16 (66.7) |

| List of EPAs designed specifically for educational programs | 6 (25.0) |

| One specific EPA or supporting task | 2 (8.3) |

| Type of educational activity with EPAs implemented | |

| Practice experiences | 15 (62.5) |

| Courses | 7 (29.2) |

| A sequence of skill lab-based courses and practice experiences | 1 (4.2) |

| All the four professional years from one PharmD program | 1 (4.2) |

| Use of EPAs in teaching and assessment | |

| Direct practice observation in practice experiences by preceptors | 19 (79.2) |

| Student self-assessment of performance through a structured form | 3 (12.5) |

| Product evaluation | 3 (12.5) |

| Case-based discussion or case-based study | 2 (8.3) |

| Reflective activity | 2 (8.3) |

| Not informed | 1 (4.2) |

| Variables | Number of Papers (%) |

|---|---|

| Facilitators | |

| Facilitate student assessment of competencies | 5 (20.8) |

| Facilitate assigning grades to the students | 3 (12.5) |

| Facilitate feedback to the students | 1 (4.2) |

| Provide additional opportunities for preceptor development | 1 (4.2) |

| Barriers | |

| Difficulties in using EPA-based instruments for assessment | 7 (29.2) |

| Heavy workload | 3 (12.5) |

| Some EPAs are not applicable to workplace settings | 3 (12.5) |

| Insufficient faculty involvement and resource constraints | 1 (4.2) |

| Recommendations | |

| Adopt more user-friendly EPA-based assessment tools | 3 (12.5) |

| Decrease the number of assessments | 1 (4.2) |

| Additional training in the EPAs’ framework and EPA-based assessments | 1 (4.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, L.C.O.A.d.; Romani, L.F.d.A.; Lima, M.G. How Have Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) Been Implemented in Pharmacy Education? A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060156

Souza LCOAd, Romani LFdA, Lima MG. How Have Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) Been Implemented in Pharmacy Education? A Scoping Review. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060156

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Luiz Claudio Oliveira Alves de, Luciana Flavia de Almeida Romani, and Marina Guimaraes Lima. 2025. "How Have Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) Been Implemented in Pharmacy Education? A Scoping Review" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060156

APA StyleSouza, L. C. O. A. d., Romani, L. F. d. A., & Lima, M. G. (2025). How Have Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) Been Implemented in Pharmacy Education? A Scoping Review. Pharmacy, 13(6), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060156