Community Pharmacist Prescribing: Roles and Competencies—A Systematic Review and Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Population (P): Community pharmacists

- Intervention (I): Prescribing roles

- Comparison (C): Traditional roles of pharmacists

- Outcome (O): Barriers and facilitators influencing practice and patient care outcomes, inferred competencies for safe and effective prescribing

- RQ1: What tasks do community pharmacists perform, and in which settings or models is prescribing carried out?

- RQ2: What legal and regulatory frameworks define pharmacists’ prescribing authority, eligibility, and permitted medications?

- RQ3: What barriers and facilitators influence community pharmacists’ prescribing practices and patient care outcomes?

- RQ4: What skills, qualifications, and competencies can be inferred for safe and effective prescribing, and how can these be assessed?

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Articles addressing the roles or prescribing practices of community pharmacists;

- Articles published between 2015 and 2025;

- Articles published in English;

- Articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals;

- Original or primary source studies, including descriptive, experimental, quasi-experimental, cross-sectional, and longitudinal designs.

- Articles not addressing community pharmacist prescribing or community pharmacist roles;

- Articles published before 2015;

- Articles published in languages other than English;

- Articles published in non-scientific journals, incomplete, or non-peer-reviewed publications;

- Secondary source studies such as reviews, editorials, and commentaries.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

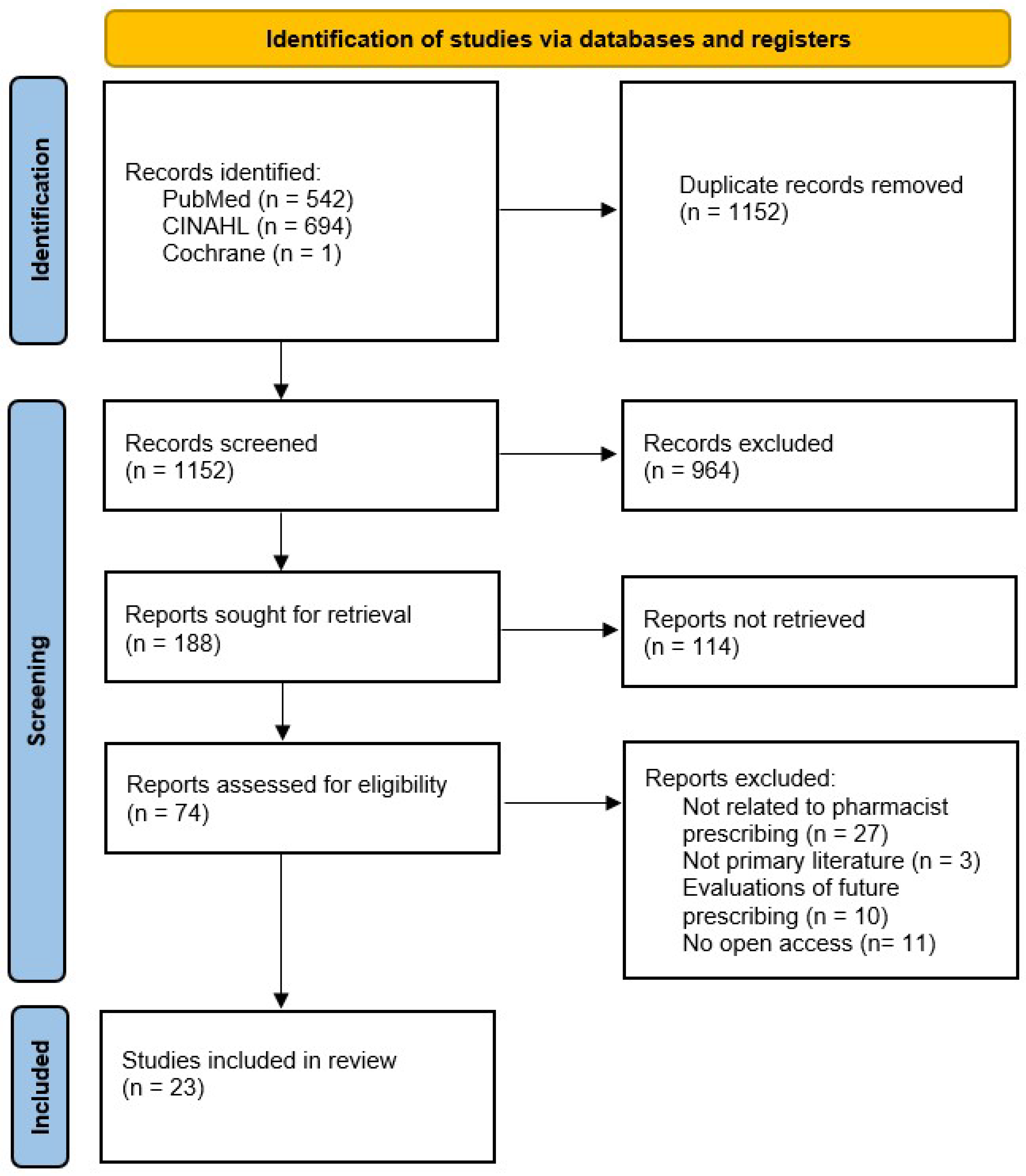

2.3. Selection Process

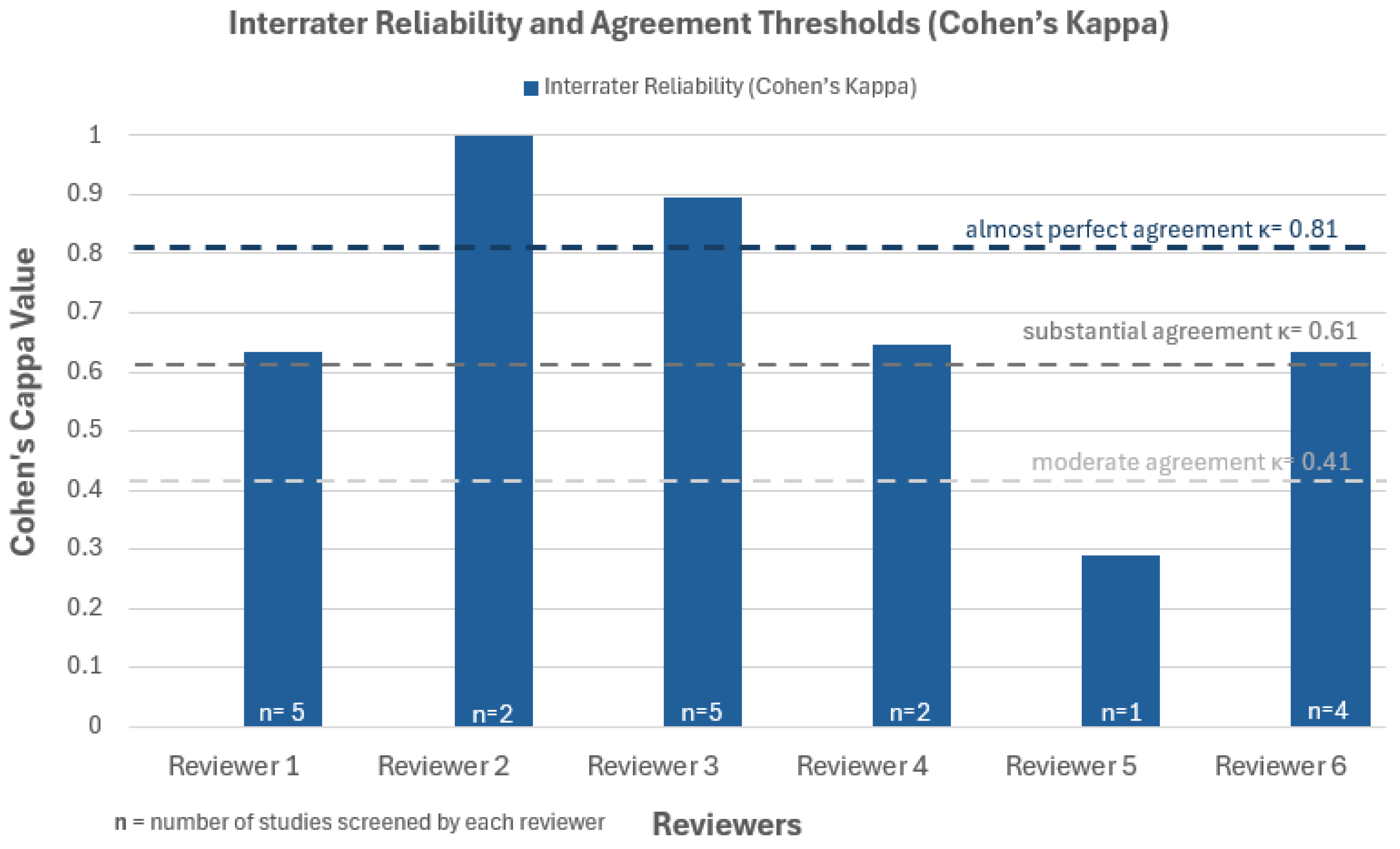

2.4. Data Collection and Risk of Bias Assessment

- High quality (≥80%)

- Moderate quality (60–79%)

- Low quality (<60%)

- <0.00 = Poor

- 0.00–0.20 = Slight

- 0.21–0.40 = Fair

- 0.41–0.60 = Moderate

- 0.61–0.80 = Substantial

- 0.81–1.00 = Almost perfect

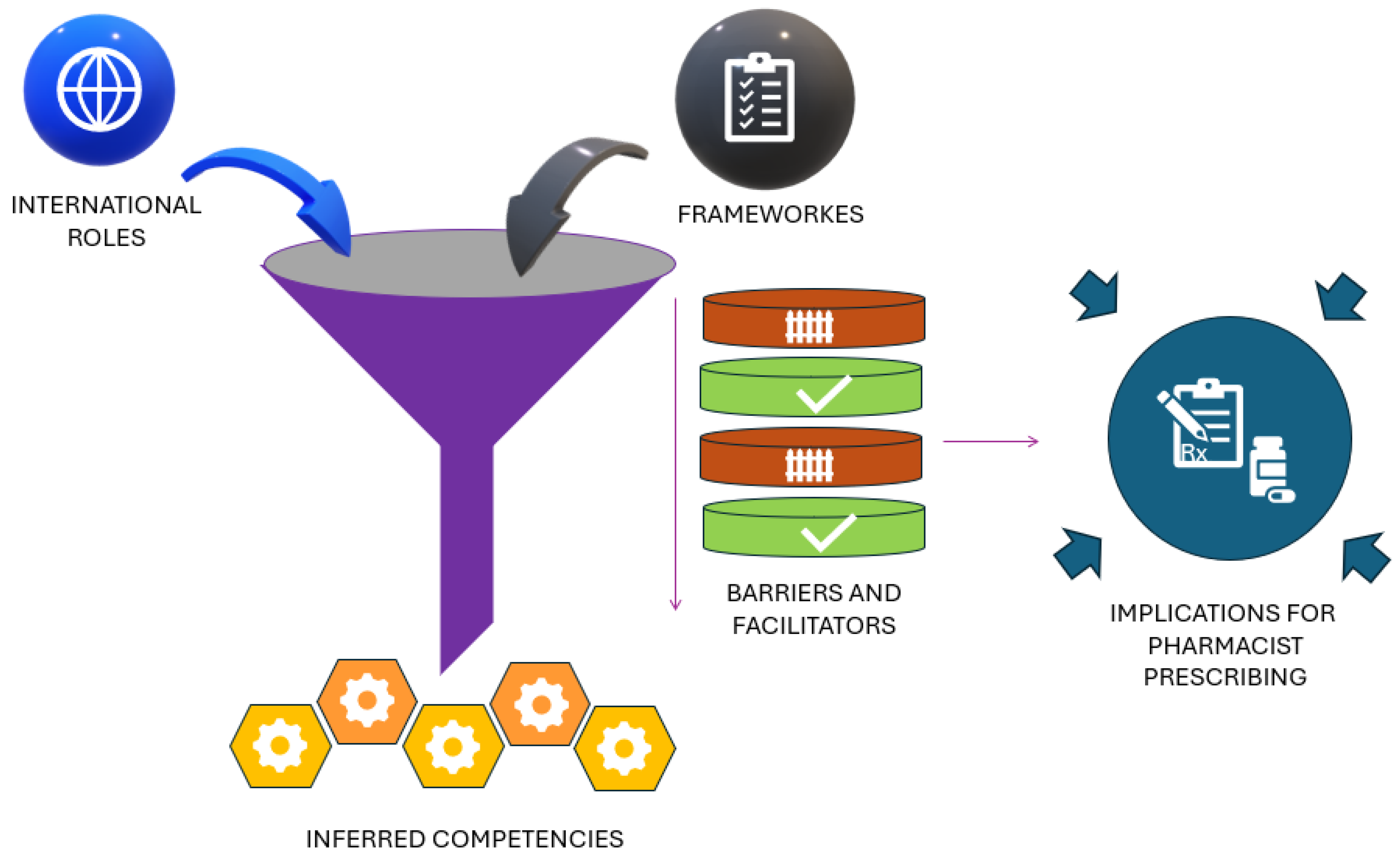

2.5. Synthesis Methods

2.6. Assessment of Reporting Bias and Certainty

3. Results

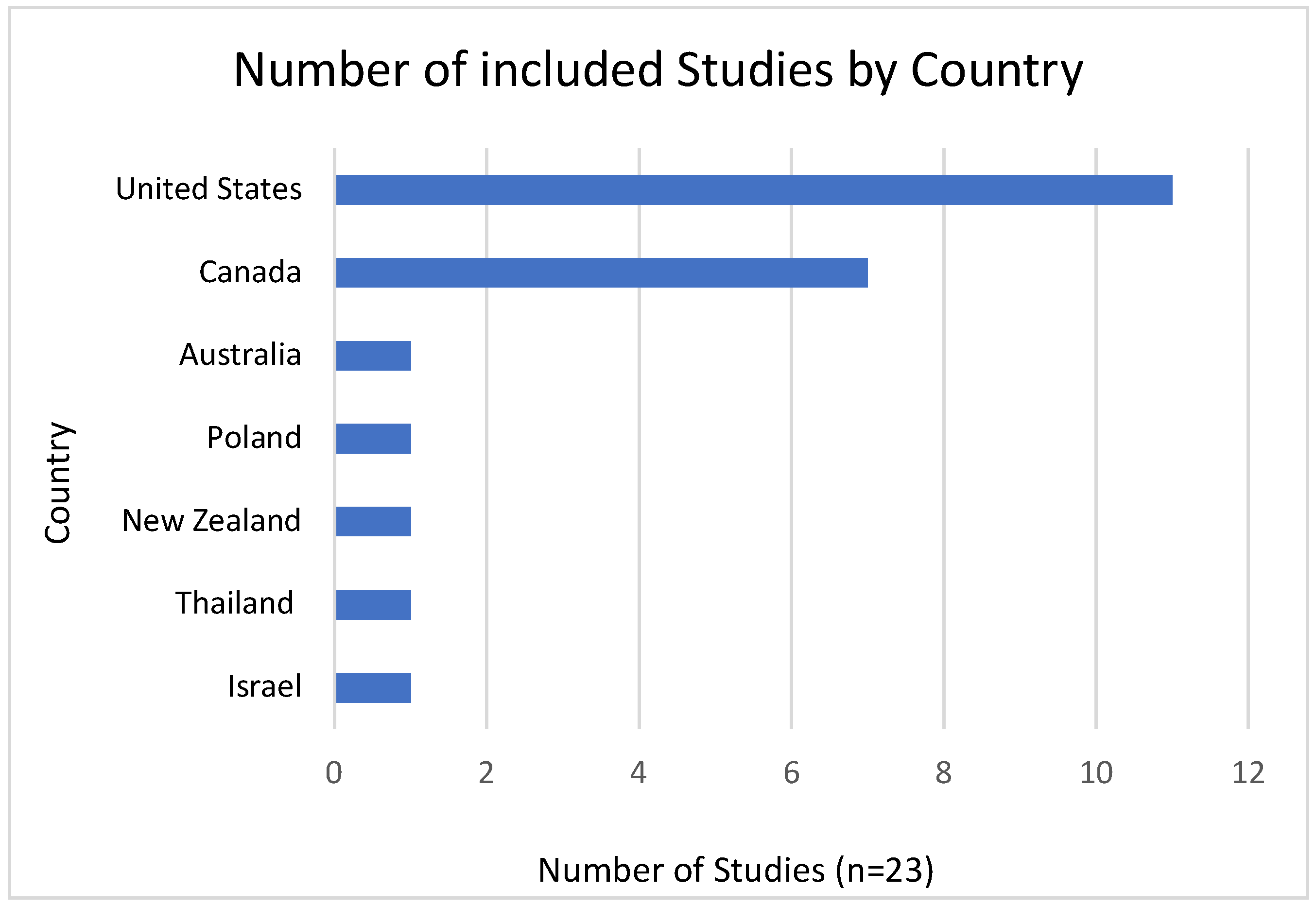

3.1. Screening Results

Study Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. Synthesis of Findings (Development of Key Themes)

3.3.1. International Role

- Clinical Role Expansion

- 2.

- Public Health and Accessibility

- 3.

- Readiness and Self-Perception

3.3.2. Regulatory Framework

- 1.

- Legal Authority and Scope

- 2.

- Emergency Exemptions and Pandemic-Driven Change

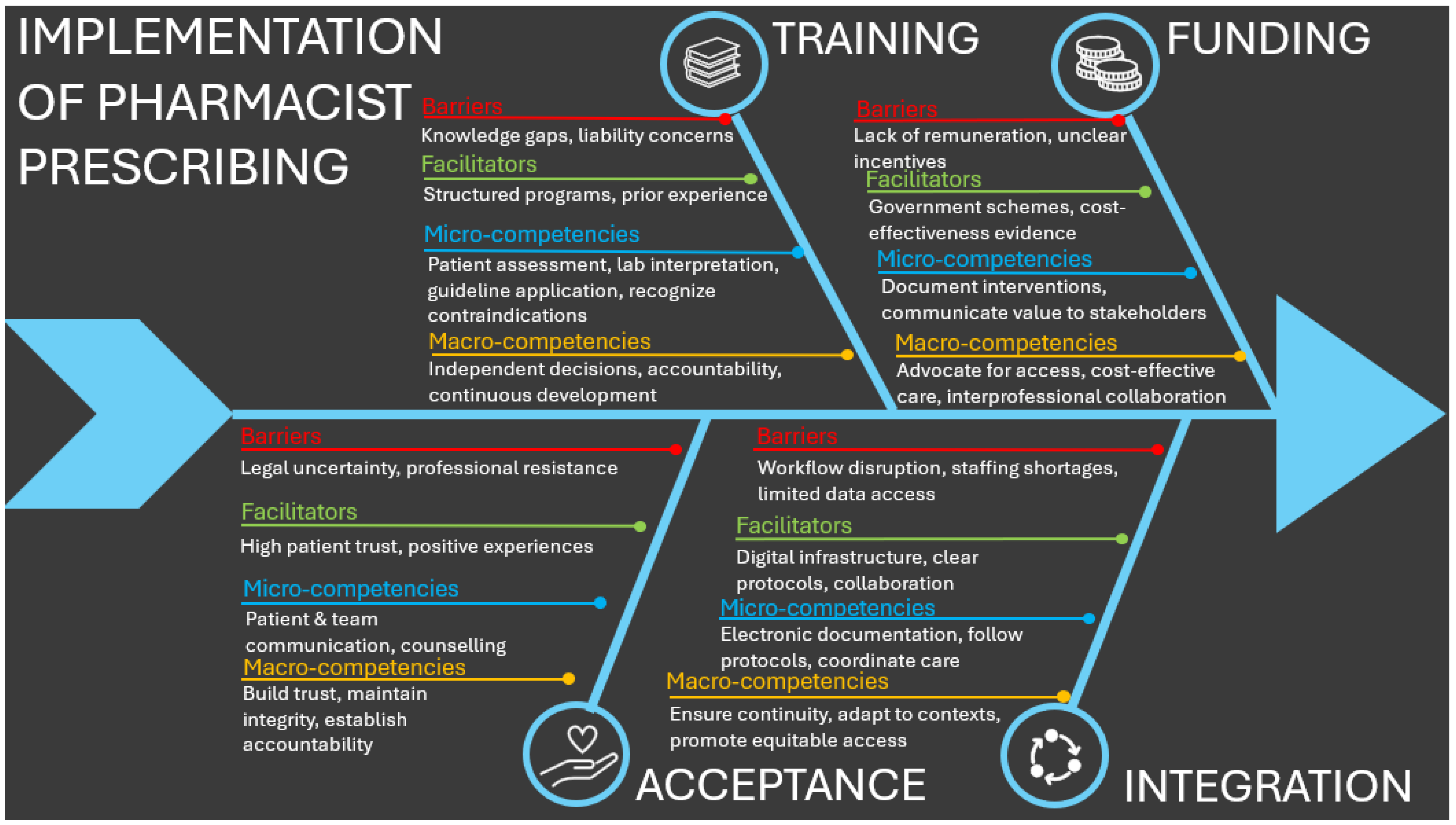

3.3.3. Barriers and Facilitators

- 1.

- Training:

- 2.

- Funding:

- 3.

- Acceptance:

- 4.

- Integration:

3.3.4. Inferred Competencies

3.3.5. Implications for Pharmacist Prescribing

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| GPs | General Practitioners |

| HbA1c | Glycosylated Hemoglobin |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| NOAC | Novel Oral Anticoagulant |

| NRK | Naloxone Rescue Kit |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| UTI | Urinary Tract Infection |

Appendix A. Risk of Bias Assessment Raw Data

| Author, Year | CASP-Tool | Raw Score | Score (%) | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 11/11 | 100 | High quality |

| [38] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 11/11 | 100 | High quality |

| [41] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 11/11 | 100 | High quality |

| [31] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 10.5/11 | 95.5 | High quality |

| [29] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 10.5/11 | 95.45 | High quality |

| [26] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 10.5/11 | 95.45 | High quality |

| [33] | Qualitative Research | 9.5/10 | 95 | High quality |

| [37] | Cohort Studies | 13/14 | 92.86 | High quality |

| [32] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 10/11 | 90.91 | High quality |

| [28] | Qualitative Research | 9/10 | 90 | High quality |

| [20] | Qualitative Research | 9/10 | 90 | High quality |

| [40] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 9.5/11 | 86.36 | High quality |

| [35] | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | 11/13 | 84.6 | High quality |

| [30] | Qualitative Research | 8/10 | 80 | High quality |

| [39] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 8.5/11 | 77.27 | Moderate quality |

| [23] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 8.5/11 | 77.27 | Moderate quality |

| [36] | Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | 10/13 | 76.92 | Moderate quality |

| [24] | Cohort Studies | 10.5/14 | 75 | Moderate quality |

| [25] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 8/11 | 72.73 | Moderate quality |

| [34] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 7/11 | 63.64 | Moderate quality |

| [27] | Systematic reviews with meta-analysis of observational studies | 6/10 | 60 | Low quality |

| [21] | Descriptive/Cross-Sectional Studies | 6/11 | 54.5 | Low quality |

| [42] | Qualitative Research | 3.5/10 | 35 | Low quality |

| Author, Year | Checklist Items | Cohen’s Kappa | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | 10 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [24] | 10 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [33] | 1 | Almost perfect | |

| [42] | 10 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [41] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [31] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [39] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [26] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [23] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [40] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [21] | 11 | 1 | Almost perfect |

| [38] | 11 | 0.48 | Moderate |

| [20] | 10 | 0.47 | Moderate |

| [25] | 11 | 0.41 | Moderate |

| [36] | 13 | 0.31 | Fair agreement |

| [29] | 11 | 0.29 | Fair agreement |

| [32] | 11 | 0,29 | Fair agreement |

| [35] | 13 | 0.29 | Fair agreement |

| [34] | 11 | 0.22 | Fair agreement |

References

- World Health Organization. Health and Care Workers: Protect. Invest. Together. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/universal-health-coverage/who-uhl-technical-brief---health-and-care-workers.pdf?sfvrsn=553b2ed5_3&download=true (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Mesbahi, Z.; Piquer-Martinez, C.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Martinez-Martinez, F.; Amador-Fernandez, N.; Zarzuelo, M.J.; Dineen-Griffin, S.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Pharmacists as independent prescribers in community pharmacy: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2025, 21, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraux, A.; Bonnan, D.; Ramond-Roquin, A.; Faure, S. The community pharmacist as an independent prescriber: A scoping review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 64, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.R. Rational prescribing: The principles of drug selection. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.J.; Weaver, K.K.; Adams, J.A. Revisiting the continuum of pharmacist prescriptive authority. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebara, T.; Cunningham, S.; MacLure, K.; Awaisu, A.; Pallivalapila, A.; Stewart, D. Stakeholders’ views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1883–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, M.R.; Ma, T.; Fisher, J.; Sketris, I.S. Independent pharmacist prescribing in Canada. Can. Pharm. J. 2012, 145, 17–23.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.; Duerden, M.; Payne, R.A. Deprescribing: A primary care perspective. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 24, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apothekerkammer, Ö. Die Österreichische Apotheke in Zahlen. The Austrian Pharmacy—Facts and Figures. 2009. Available online: https://docplayer.org/73957142-Die-oesterreichische-apotheke-in-zahlen-the-austrian-pharmacy-facts-and-figures.html (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Rose, O.; Eppacher, S.; Pachmayr, J.; Clemens, S. Vitamin D testing in pharmacies: Results of a federal screening campaign. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2025, 18, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apothekerkammer, Ö. Rezeptpflichtgesetz, § 4 Abs. 6 1972. Available online: https://www.apothekerkammer.at/infothek/rechtliche-hintergruende/arzneimittelrecht/rezeptpflichtgesetz (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Rose, O.; Egel, C.; Johanna, P.; Clemens, S. Pharmacist-Led Prescribing in Austria: A Mixed-Methods Study on Clinical Readiness and Legal Frameworks. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Commission. Health at a Glance: Europe 2024: State of Health in the EU Cycle. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-europe-2024_b3704e14-en.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Santos, C.M.; de Mattos Pimenta, C.A.; Nobre, M.R. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CASP, C.A.S.P. 2023. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Gisev, N.; Bell, J.S.; Chen, T.F. Interrater agreement and interrater reliability: Key concepts, approaches, and applications. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2013, 9, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafie, S.; Richards, E.; Rafie, S.; Landau, S.C.; Wilkinson, T.A. Pharmacist Outlooks on Prescribing Hormonal Contraception Following Statewide Scope of Practice Expansion. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.; Su, J.; Nguyen, M.; Ly, M.; Wu, I.; Tracy, D.; Song, A.; Apollonio, D.E. Pharmacist furnishing of hormonal contraception in California’s Central Valley. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2024, 64, 226–234.e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.H.; Rafie, S.; Griffin, B.; Shealy, K.; Stein, A.B. Pharmacist self-perception of readiness to prescribe hormonal contraception and additional training needs. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2020, 12, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spann, N.; Hamper, J.; Griffith, R.; Cleveland, K.; Flynn, T.; Jindrich, K. Independent pharmacist prescribing of statins for patients with type 2 diabetes: An analysis of enhanced pharmacist prescriptive authority in Idaho. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, S108–S114.e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Hartung, D.M.; Middleton, L.; Rodriguez, M.I. Pharmacist Provision of Hormonal Contraception in the Oregon Medicaid Population. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachyrycz, A.; Shrestha, S.; Bleske, B.E.; Tinker, D.; Bakhireva, L.N. Opioid overdose prevention through pharmacy-based naloxone prescription program: Innovations in health care delivery. Subst. Abus. 2017, 38, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Rafie, S.; Zhang, Z.; Singh, A.V.; Bird, C.E.; Sridhar, A.; Sullivan, J.G. An Evaluation of the Implementation of Pharmacist-Prescribed Hormonal Contraceptives in California. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingman, D.A.; Schmit, C.D. Authority of Pharmacists to Administer Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Alignment of State Laws with Age-Level Recommendations. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, A.M.; McCullough, C.; Fadda, R.; Ganguly, B.; Gustafson, E.; Severson, N.; Tomlitz, J. Facilitators and barriers to implementing pharmacist-prescribed hormonal contraception in California independent pharmacies. Women Health 2020, 60, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, K.; Rafie, S.; Grindlay, K.; Gutierrez, H.; Grossman, D. Pharmacist Intentions to Prescribe Hormonal Contraception Following New Legislative Authority in California. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 32, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.; McCauley, G.; Thaxton, L.; Borrego, M.; Sussman, A.L.; Espey, E. Perspectives on prescribing hormonal contraception among rural New Mexican pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2020, 60, e57–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Trenaman, S.; Stewart, S.; Liu, L.; Fisher, J.; Jeffers, E.; Lawrence, R.; Murphy, A.; Sketris, I.; Woodill, L.; et al. Uptake of community pharmacist prescribing over a three-year period. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 9, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.; Rowe, L.; Kennie-Kaulbach, N.; Bishop, A.; Kontak, J.; Stewart, S.; Morrison, B.; Sketris, I.; Rodrigues, G.; Minard, L.V.; et al. Increased self-reported pharmacist prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Using the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and facilitators to prescribing. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, L.D.; Rosenberg-Yunger, Z.R.S. Pharmacists expanded role in providing care for opioid use disorder during COVID-19: A qualitative study exploring pharmacists’ experiences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 232, 109303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, K.; Bootsman, N.; Kuntz, A.; Taylor, J. Evaluating pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 23, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, R.K.; Fradette, M.; Lin, M.; Youngson, E.; Lau, D.; Bungard, T.J.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Dolovich, L.; Healey, J.S.; McAlister, F.A. Stroke Risk Reduction in Atrial Fibrillation Through Pharmacist Prescribing: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2421993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyuki, R.T.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N.; Jones, C.A.; Hemmelgarn, B.R. The Effectiveness of Pharmacist Interventions on Cardiovascular Risk: The Multicenter Randomized Controlled RxEACH Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodill, L.; Bodnar, A. A novel model of care in anticoagulation management. Healthc. Manag. Forum. 2020, 33, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ung, E.; Czarniak, P.; Sunderland, B.; Parsons, R.; Hoti, K. Assessing pharmacists’ readiness to prescribe oral antibiotics for limited infections using a case-vignette technique. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauld, N.J.; Zeng, I.S.; Ikram, R.B.; Thomas, M.G.; Buetow, S.A. Antibiotic treatment of women with uncomplicated cystitis before and after allowing pharmacist-supply of trimethoprim. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laopaiboonkun, S.; Chuaychai, A.; Yommudee, K.; Puttasiri, P.; Petchluan, S.; Thongsutt, T. Antibiotic prescribing for acute uncomplicated cystitis among community pharmacists in Thailand. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 32, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Placzek, J.; Wrzosek, N.; Owczarek, A. Assessment of Pharmacists Prescribing Practices in Poland—A Descriptive Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzberg, E.; Nathan, J.P.; Avron, S.; Marom, E. Clinical and other specialty services offered by pharmacists in the community: The international arena and Israel. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2018, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.I.; Dainty, A.R.J.; Moore, D.R. Towards a multidimensional competency-based managerial performance framework. J. Manag. Psychol. 2005, 20, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Desborough, J.; Parkinson, A.; Douglas, K.; McDonald, D.; Boom, K. Barriers to pharmacist prescribing: A scoping review comparing the UK, New Zealand, Canadian and Australian experiences. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, F.; Akel, M.; Sacre, H.; Haddad, C.; Tawil, S.; Safwan, J.; Hajj, A.; Zeenny, R.M.; Iskandar, K.; Salameh, P. The specialized competency framework for community pharmacists (SCF-CP) in Lebanon: Validation and evaluation of the revised version. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2023, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NPS MedicineWise. Prescribing Competencies Framework: Embedding Quality Use of Medicines into Practice 2021. Available online: https://www.nps.org.au/assets/NPS/pdf/NPS-MedicineWise_Prescribing_Competencies_Framework.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Jusline.at. § 36a ApoG—Apothekengesetz. 2024. Available online: https://www.jusline.at/gesetz/apog/paragraf/36a (accessed on 30 September 2025).

| Database | Search Date | Search String (Descriptors & Boolean Operators) |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 20 January 2025 | ((community AND pharmacist AND prescribing AND service AND pharmacy) NOT hospital) |

| CINAHL (EBSCOhost) | 21 January 2025 | ((community AND pharmacist AND prescribing AND service AND pharmacy) NOT hospital) |

| Cochrane Library (Ovid) | 22 January 2025 | ((community AND pharmacist AND prescribing AND service AND pharmacy) NOT hospital) |

| Authors, Year | Country | Study Design | Focus and Key Area | Population/Medication(s) | Barriers (−)/Facilitators (+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mansell et al., 2015 [34] | Canada (Saskatchewan) | Cross-sectional survey | Patient-reported outcomes (incl. satisfaction, and health-seeking) after pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists Medication(s): Various prescription agents for minor ailments (e.g., antiviral creams, antihistamines, antibiotics) | − Lack of feedback for most events, limited capture of minor ailment prescriptions + High patient satisfaction with symptomatic improvement and service quality, with most patients trusting pharmacists |

| Tsuyuki et al., 2016 [36] | Canada (Alberta) | Multicenter RCT | Cardiovascular risk management (pharmacist-led case finding, prescribing, and test-and-treat interventions) Key areas: Current role; Prescribing settings and models; Barriers and facilitators) | Community pharmacists (n = 56 sites), patients at high cardiovascular risk (n = 723) Medication(s): Antihypertensives, lipid-lowering agents, antidiabetics, smoking cessation aids | − Short follow-up as targeted outcomes [Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C), blood pressure, HbA1c, sustained smoking cessation] require longer to show full effects. + Improved clinical outcomes (significantly reduced cardiovascular risk and improved control of blood pressure, lipids, glycemic status, and smoking cessation); pharmacist training program |

| Bachyrycz et al., 2017 [25] | United States (New Mexico) | Registry analysis | Implementation of naloxone prescribing Key areas: Regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists certified under the Naloxone Pharmacist Prescriptive Authority Program (n = 196); patients at risk of opioid overdose [n = 133 reported Naloxone Rescue Kit (NRK) prescriptions] Medication(s): Naloxone (intranasal, via NRK) | − Rural access, limited pharmacist certification, stigma, reimbursement + Direct access, patient engagement |

| Ung et al., 2017 [38] | Australia (Western Australia) | Quantitative cross-sectional survey using case vignette methodology | Prescribing appropriateness for infections (prescribing oral antibiotics) Key areas: Current role; Prescribing settings and models; Barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists (n = 82); 425 case vignette responses across various infection types Medication(s): Amoxicillin, trimethoprim, flucloxacillin, cephalexin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | − Diagnostic uncertainty (specifically in complex infections), training needs + High prescribing confidence for common infections: Urinary Tract Infection (UTIs), cellulitis, and acne |

| Gauld et al., 2017 [39] | New Zealand | Before-and-after study | Trimethoprim supply in women with uncomplicated cystitis and stewardship Key areas: Regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists (n = 139 pharmacies pre, n = 120 post), women aged 16–65 with uncomplicated cystitis Medication(s): Trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin | − Low uptake, public awareness gaps + Guideline-conformant prescribing; effective stewardship |

| Batra et al., 2018 [26] | United States (California) | Telephone mystery shopper survey | Access to hormonal contraception Key areas: regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Retail pharmacies in California (n = 457), stratified by rurality and pharmacy type Medication(s): Hormonal contraceptives (pill, patch, ring, injection) | − Low pharmacists’ service participation, unclear incentives, variable implementation fidelity + Pharmacists‘ protocol compliance |

| Dingman et al., 2018 [27] | United States (50 states + District of Columbia) | Legal analysis using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Public Health Law Program database and standardized coding algorithm | HPV vaccine authority across states Key areas: Regulatory framework; Barriers and facilitators | Not applicable (legal jurisdictions) Medication(s): HPV vaccine | − Age restrictions (only 22 states permitted vaccination of 11–12-year-olds, many laws imposed age restrictions or required prescriber involvement, limiting access) + Legal access in many states: n = 5 allowed prescriptive authority (no third party), n = 32 allowed general third-party authorization, and n = 3 required patient-specific authorization |

| Schwartzberg et al., 2018 [42] | Israel (with international comparison) | Policy review | Comparison of pharmacist service models (Israel vs. International) Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Not applicable Medication(s): Emergency supply, statins, antihypertensives, inhaled corticosteroids, and vaccines | − Lack of time, insufficient remuneration, limited access to medical records + Expanded legal authority in Israel (prescribing, vaccination, and emergency dispensing)—aligning with international trends |

| Anderson et al., 2019 [24] | United States (Oregon) | Retrospective Medicaid claims analysis | Evaluation of contraceptive pharmacist-led prescribing Key areas: Prescribing settings and models, Regulatory framework | community pharmacists (n = 162) Medication(s): combined oral contraceptive pills, progestin-only pills, transdermal patches | − Racial access disparities + High reach among new users |

| Vu et al., 2019 [29] | United States (California) | Cross-sectional survey | Readiness to prescribe contraception Key areas: Current role; Barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists in California (n = 121) Medication(s): hormonal contraceptives | − Time constraints, liability concerns, lack of reimbursement + High comfort and intent with clinical tasks such as identifying contraindications and providing patient education. |

| Rafie et al., 2019 [20] | United States (California) | Semi-structured interviews | Pharmacists’ perspectives on prescribing hormonal contraception prior to statewide protocol implementation. Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; regulatory framework; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists (n = 30) from urban, suburban, and rural settings Medication(s): hormonal contraceptives (pill, patch, ring, injection) | − Knowledge gaps, religious objections, limited private space, reimbursement issues, liability concerns. + Public health benefit of expanded access and willingness to participate under appropriate conditions |

| Gomez et al., 2020 [28] | United States (California) | Structured telephone interviews | Implementation in independent pharmacies Key area: Barriers and facilitators | Pharmacists (n = 36) from independent pharmacies Medication(s): Hormonal contraceptives | − Lack of reimbursement, business risks, liability concerns, and time/resource limitations impeded implementation. + Support of the expansion of roles and high potential to increase access. |

| Stone et al., 2020 [22] | United States (21 states) | Cross-sectional survey | Training needs for contraception prescribing Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; barriers and facilitators | Pharmacists in 21 US states (n = 823) Medication(s): Hormonal contraceptives (pill, patch, ring, injection) | − Inadequate curriculum coverage, limited familiarity with clinical guidelines, and preference for additional training formats + Higher confidence with experience or residency training and readiness to prescribe |

| Herman et al., 2020 [30] | United States (New Mexico) | Semi-structured telephone interviews | Rural pharmacists’ readiness in prescribing contraception Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; regulatory framework | Rural community pharmacists (n = 21) from diverse regions across New Mexico Medication(s): Hormonal contraceptives (pill, patch, ring, injection) | − Insufficient training, lack of reimbursement, and liability concerns, with limited support infrastructure in rural practice settings. + Pharmacists recognized their accessibility and trusted rural role, expressing willingness to expand contraception prescribing. |

| Spann et al., 2020 [23] | United States (Idaho) | Pilot study | Implementation and patient acceptance of pharmacist-led statin prescribing for type 2 diabetes. Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists in four Albertsons pharmacies, patients with type 2 diabetes eligible for statin therapy Medication(s): moderate-intensity statins | − Difficulty contacting patients, delays due to mail-in lab tests, and a lack of integration with electronic health records. + Positive patient perception and successful implementation |

| Woodill and Bodnar, 2020 [37] | Canada (Nova Scotia) | Evaluation of Community Pharmacist-led Anticoagulation Management Service based on qualitative and quantitative data | Model evaluation based on Point-of-care International Normalized Ratio (INR) test, assessment and dosage adjustment prescribing, counselling and providing support in adherence tools Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; barriers and facilitators | Community Pharmacists (n = 106), patients (n = 946), primary care providers (n = 237; physicians = 225, nurse practitioners = 12) Medication(s): Warfarin, Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) | − Manufacturer test strip error (was not identified) + Effective prescribing model; improved time in therapeutic range outcomes for patients. In addition, cost-effective solution for health systems |

| Zimmermann et al., 2021 [41] | Poland | Retrospective data analysis | COVID-related expansion of prescribing from emergency-only to broad pharmacist prescribing Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Pharmacists from community pharmacies (n = 842) and national prescribing dataset (n = 18,529 prescriptions Medication(s): Cardiovascular, respiratory, dermatological, alimentary tract, nervous system, anti-infectives | − Lack of reimbursement, unclear legal definitions of “health risk” limited practical implementation + Expanded legal access across various conditions including chronic diseases and minor ailments, significantly increasing access |

| Bishop & Rosenberg-Yunger, 2022 [33] | Canada | Semi-structured interviews | Examination of Canadian pharmacists’ use of an emergency exemption to provide opioid agonist therapy during COVID-19 Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; regulatory framework; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community and primary care pharmacists (n = 19) who used the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act exemption Medication(s): Opioid agonist therapy (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone, hydromorphone) | − Stigma, lack of training and infrastructure, time burden, and variability in pharmacy willingness to provide opioid use disorder services. + Improved continuity of care, facilitate harm reduction, and expand access through clinical assessments, prescription transfers, and emergency supplies. |

| Grant et al., 2023 [32] | Canada (Nova Scotia) | Cross-sectional survey | Prescribing changes during COVID-19 Key areas: prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists (n = 190) prescribing, Medication(s): Antibiotics, hormonal contraceptives, antifungals, antivirals, antihistamines, smoking cessation aids, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) treatments, acne therapy, vaccines | − Lack of remuneration, staffing shortages, and workflow constraints + Increase in prescribing volume particularly for government-funded services and in categories like renewals and uncomplicated cystitis. |

| Grant et al., 2023 [31] | Canada (Nova Scotia) | Cohort study based on health data | Prescribing trends and access over 3 years Key areas: current role of community pharmacists; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists in Nova Scotia (n = 1182); patient cohort (n = 372.203) Medication(s): GERD treatments, vaccines, contraceptives, antibiotics, smoking cessation aids | − Socioeconomic gaps, lower uptake in urban/high-income areas, logistical challenges related to reimbursement and lab integration. + Increased prescribing; high uptake for approved conditions such as GERD, vaccination, and contraception; care gaps in underserved populations. |

| Laopaiboonkun et al., 2024 [40] | Thailand | Cross-sectional survey | Guideline adherence in UTI prescribing Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists (n = 349) Medication(s): ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin | − Diagnostic confusion in distinguishing between complicated and uncomplicated cystitis, highlighting diagnostic gaps, especially, especially in older pharmacists + Strong guideline adherence |

| Azad et al., 2024 [21] | United States (California—Central Valley) | Mixed-methods study | Contraception access in rural areas Key areas: Prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacists in 11 Central Valley counties (n = 576 pharmacies contacted, n = 75 furnishing) Medication(s): hormonal contraceptives (oral contraceptives) | − Lack of reimbursement, low public awareness, limited pharmacist certification, and time/staffing constraints + High accessibility, privacy, cost-effectiveness |

| Sandhu et al., 2024 [35] | Canada (Alberta) | RCT | Evaluation of anticoagulant prescribing in atrial fibrillation Key areas: Current role of community pharmacists; prescribing settings and models; barriers and facilitators | Community pharmacies (n = 27); patients with untreated or undertreated atrial fibrillation (n = 80) Medication(s): Oral anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, apixaban, rivaroxaban) | − Recruitment and physician resistance, logistical constraints such as the COVID-19 pandemic + Increased guideline-concordant anticoagulant, better patient adherence, satisfaction, guideline use |

| Role | Legal/Regulatory Framework | Micro-Competency (Professional Skills) | Macro-Competency (Person-Level, Overarching) | Role Context/Performance (Professional Excellence in Social Context) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Role Expansion |

|

|

| Role involves exercising independent clinical judgment, collaborating effectively with healthcare teams, and adapting practices to dynamic patient and organizational contexts, demonstrating professional excellence and accountability |

| Public Health and Accessibility |

|

|

| Role requires balancing public health priorities with patient safety, promoting equitable access, and contributing to community health, enacting professional responsibility in societal contexts |

| Readiness and Self-Perception |

|

|

| Role emphasizes safe and accountable prescribing, reflective practice, and continuous adaptation to evolving professional responsibilities, reinforcing trust and professional integrity within social and healthcare contexts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clemens, S.; Eisl-Raudaschl, L.; Pachmayr, J.; Rose, O. Community Pharmacist Prescribing: Roles and Competencies—A Systematic Review and Implications. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060157

Clemens S, Eisl-Raudaschl L, Pachmayr J, Rose O. Community Pharmacist Prescribing: Roles and Competencies—A Systematic Review and Implications. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060157

Chicago/Turabian StyleClemens, Stephanie, Lea Eisl-Raudaschl, Johanna Pachmayr, and Olaf Rose. 2025. "Community Pharmacist Prescribing: Roles and Competencies—A Systematic Review and Implications" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060157

APA StyleClemens, S., Eisl-Raudaschl, L., Pachmayr, J., & Rose, O. (2025). Community Pharmacist Prescribing: Roles and Competencies—A Systematic Review and Implications. Pharmacy, 13(6), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060157