Hospital Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions: A Nationwide Validation Study in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures and Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Background Data

3.2. Confirming the Questionnaire Domains

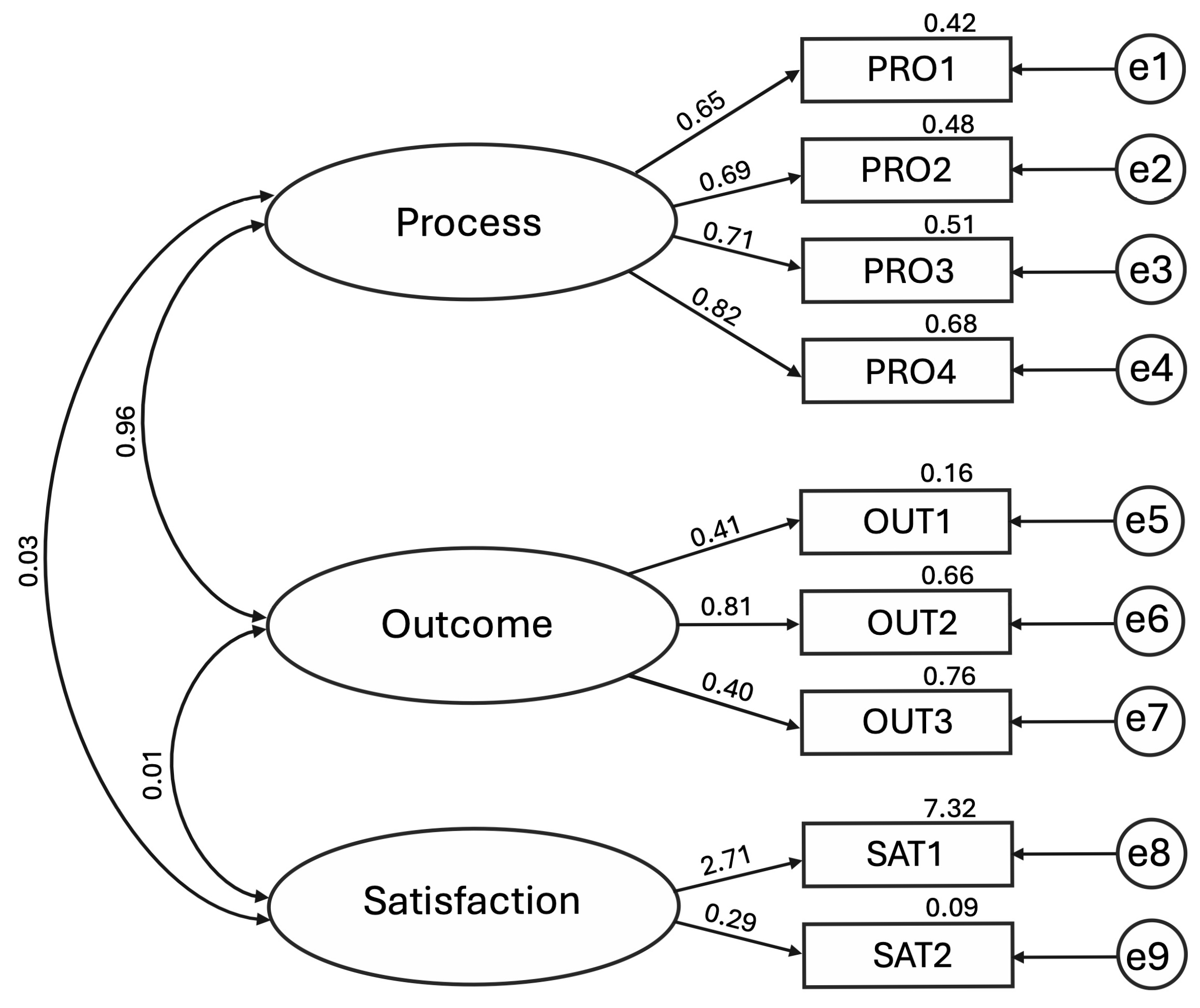

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMOS | Analysis of Moment Structures |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CPOE | Computerised Physician Order Entry |

| DRP | Drug-Related Problem |

| EAHP | European Association of Hospital Pharmacists |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

| LHU | Local Health Unit |

| LTCFs | Long-Term Care Facilities |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| OUT | Outcome (Latent Factor) |

| PCLOSE | P of Close Model Fit |

| PCNE | Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe |

| PI | Pharmacist Intervention |

| PRO | Process (Latent Factor) |

| RFI | Relative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SAT | Satisfaction (Latent Factor) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error of Unstandardised Regression Weights |

| SRW | Standardised Regression Weights |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| URW | Unstandardised Regression Weights |

| χ2 | Chi-square |

References

- Delgado-Silveira, E.; Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés, M.; Muñoz-García, M.; Correa-Pérez, A.; Álvarez-Díaz, A.M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J. Effects of Hospital Pharmacist Interventions on Health Outcomes in Older Polymedicated Inpatients: A Scoping Review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 509–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.A.; Jalal, Z.; Cheema, E.; Haque, M.S.; Jenkins, D.; Yahyouche, A. Impact of the Pharmacist-Led Intervention on the Control of Medical Cardiovascular Risk Factors for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in General Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, A.; Sloeserwij, V.; Pouls, B.; Leendertse, A.; de Gier, H.; Bouvy, M.; de Wit, N.; Zwart, D. Clinical Pharmacists in Dutch General Practice: An Integrated Care Model to Provide Optimal Pharmaceutical Care. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarenne, J.; Mongaret, C.; Vermorel, C.; Bosson, J.L.; Gangloff, S.C.; Lambert-Lacroix, S.; Bedouch, P. Characteristics of Hospital Pharmacist Interventions and Their Clinical, Economic and Organizational Impacts: A Five-Year Observational Study on the French National Observatory. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 47, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calloway, S.; Akilo, H.; Bierman, K. Impact of a Clinical Decision Support System on Pharmacy Clinical Interventions, Documentation Efforts, and Costs. Hosp. Pharm. 2013, 48, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatiha Mahomedradja, R.; Wang, S.; Catherina, K.; Sigaloff, E.; Tichelaar, J.; Adriaan Van Agtmael, M. Hospital-Wide Interventions for Reducing or Preventing in-Hospital Prescribing Errors: A Scoping Review. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2025, 24, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.; Falcão, F.; das Cavaco, A.M. Documentation and Classification of Hospital Pharmacist Interventions: A Scoping Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 90, 722–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.A.; Wolverton, D.; Stamopoulos, M.; Zunich, R.; Niznik, J.; Ferreri, S.P. An EHR-Based Method to Structure, Standardize, and Automate Clinical Documentation Tasks for Pharmacists to Generate Extractable Outcomes. JAMIA Open 2023, 6, ooad034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossart, A.R.; Canning, M.L.; Yong, F.R.; Freeman, C.R. Benchmarking Hospital Clinical Pharmacy Practice Using Standardised Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2431181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpiat, B.; Conort, O.; Juste, M.; Rose, F.; Roubille, R.; Bedouch, P.; Allenet, B. The French Society of Clinical Pharmacy ACT-IP© Project: Ten Years Onward, Results and Prospects. Pharm. Hosp. Clin. 2015, 50, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, K.A.; Tremp, R.M.; Hersberger, K.E.; Lampert, M.L.; GSASA Working group on clinical pharmacy. Demonstrating the Clinical Pharmacist’s Activity: Validation of an Intervention Oriented Classification System. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 37, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, S.; Steurbaut, S.; Cortoos, P.J.; Wuyts, S.C.M. Development and Partial Validation of Be-CLIPSS: A Classification System for Hospital Clinical Pharmacy Activities. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 46, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.; Falcão, F.; Cavaco, A.M. Development and Validation of a Feasible Questionnaire to Assess Pharmacists’ Attitudes to Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions in Hospital Settings. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.R. Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis to Manage Discriminant Validity Issues in Social Pharmacy Research. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D. Assessing Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Fit and Model Revision, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780195339888. [Google Scholar]

- Assembleia da República. Lei n.o 131/2015—Estatuto Da Ordem Dos Farmacêuticos; Diário da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015; pp. 7010–7048.

- Hochhold, D.; Nørgaard, L.S.; Stewart, D.; Weidmann, A.E. Identification, Classification, and Documentation of Drug Related Problems in Community Pharmacy Practice in Europe: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2025, 47, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenet, B.; Bedouch, P.; Rose, F.-X.; Escofier, L.; Roubille, R.; Charpiat, B.; Juste, M.; Conort, O. Validation of an Instrument for the Documentation of Clinical Pharmacists’ Interventions. Pharm. World Sci. 2006, 28, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–462. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker, R.; Lomax, R. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-84169-890-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Hampshire, UK, 2009; ISBN 9353501350. [Google Scholar]

- Farmacêuticos em Números—Ordem dos Farmacêuticos. Available online: https://www.ordemfarmaceuticos.pt/pt/numeros/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Schepers, G. Pharmacist Intervention Documentation in US Health Care Systems. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 38, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHPA Committee of Specialty Practice in Clinical Pharmacy. SHPA Standards of Practice for Clinical Pharmacy. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2013, 43, S42–S46. [Google Scholar]

- Al-jedai, A.; Nurgat, Z.A. Electronic Documentation of Clinical Pharmacy Interventions in Hospitals. In Data Mining Applications in Engineering and Medicine; Karahoca, A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-4286-7. [Google Scholar]

- Langebrake, C.; Ihbe-Heffinger, A.; Leichenberg, K.; Kaden, S.; Kunkel, M.; Lueb, M.; Hilgarth, H.; Hohmann, C. Nationwide Evaluation of Day-to-Day Clinical Pharmacists’ Interventions in German Hospitals. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, C.P.; Farmer, C. A Brief Analysis of Clinical Pharmacy Interventions Undertaken in an Australian Teaching Hospital. J. Qual. Clin. Pract. 2001, 21, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihbe-Heffinger, A.; Langebrake, C.; Hohmann, C.; Leichenberg, K.; Hilgarth, H.; Kunkel, M.; Lueb, M.; Schuster, T. Prospective Survey-Based Study on the Categorization Quality of Hospital Pharmacists’ Interventions Using DokuPIK. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-da-Silva, R.; Alves, J.M.; Vieira, C.; Silva, A.M.; Marques, J.; Morato, M.; Polónia, J.J.; Ribeiro-Vaz, I. Motivation and Knowledge of Portuguese Community Pharmacists Towards the Reporting of Suspected Adverse Reactions to Medicines: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Community Health 2022, 48, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, S.; Underhill, J.; Horák, P.; Batista, A.; Miljkovic, N.; Gibbons, N. EAHP European Statements Survey 2018, Focusing on Section 1: Introductory Statements and Governance, Section 3: Production and Compounding, and Section 4: Clinical Pharmacy Services. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2019, 29, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruc Poje, D.; William Fitzpatrick, R.; Stevens, C.; Machin, C.; Underhill, J.; Horák, P.; Batista, A.; Süle, A.; Miljković, N.; Plesan, C.; et al. Investigation of the Hospital Pharmacy Profession in Europe. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2024, 32, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafourifard, M. Survey Fatigue in Questionnaire Based Research: The Issues and Solutions. J. Caring Sci. 2024, 13, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushanab, D.; Atchan, M.; Elajez, R.; Elshafei, M.; Abdelbari, A.; Hail, M.A.; Abdulrouf, P.V.; El-Kassem, W.; Ademi, Z.; Fadul, A.; et al. Economic Impact of Clinical Pharmacist Interventions in a General Tertiary Hospital in Qatar. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, A.; Gillibert, A.; Membre, S.; Mondet, L.; Lenglet, A.; Mary, A. Acceptance Factors for In-Hospital Pharmacist Interventions in Daily Practice: A Retrospective Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 811289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langebrake, C.; Hohmann, C.; Lezius, S.; Lueb, M.; Picksak, G.; Walter, W.; Kaden, S.; Hilgarth, H.; Ihbe-Heffinger, A.; Leichenberg, K. Clinical Pharmacists’ Interventions across German Hospitals: Results from a Repetitive Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, D.S.; Alavandi, P.; Allen, J.M.; Avery, L.M.; Buatois, E.; Connor, K.A.; Martello, J.L.; Michienzi, S.M.; Trujillo, T.C.; Ybarra, J.; et al. Addressing Challenges of Providing Remote Inpatient Clinical Pharmacy Services. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzour, A.S.; Hoad-Reddick, G.; Shahid, M.; Steinke, D.T.; Tully, M.P.; Williams, S.D.; Lewis, P.J. Patient Prioritisation for Hospital Pharmacy Services: Current Approaches in the UK. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2021, 28, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.M.; Veettil, S.K.; Donaldson, D.; Kategeaw, W.; Hutubessy, R.; Lambach, P.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. The Impact of Pharmacist Involvement on Immunization Uptake and Other Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1499–1513.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.S.; Silva, M.P.; Miranda, Í.K.S.P.B.; Calumby, R.T.; de Araújo-Calumby, R.F. Impact of Clinical Pharmacy in Oncology and Hematology Centers: A Systematic Review. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 27, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, C.; Dura, J.; Tran, A.; Lam, S.W.; Naelitz, B.; Willner, M.; Geyer, K. Effect of Clinical Pharmacist Interventions on Cost in an Integrated Health System Specialty Pharmacy. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2021, 27, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N.R.; Armistead, L.T.; Blanchard, C.M.; Rhoney, D.H. The Pharmacist’s Professional Identity: Preventing, Identifying, and Managing Medication Therapy Problems as the Medication Specialist. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 4, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwez, M.; Chanoine, S.; Lepelley, M.; Vo, T.H.; Pluchart, H.; Mazet, R.; Allenet, B.; Pison, C.; Briault, A.; Saint-Raymond, C.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of Pharmacists’ Interventions on Multidisciplinary Lung Transplant Outpatients’ Management: Results of a 7-Year Observational Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaudin, P.; Boyer, L.; Esteve, M.A.; Bertault-Peres, P.; Auquier, P.; Honore, S. Do Pharmacist-Led Medication Reviews in Hospitals Help Reduce Hospital Readmissions? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 82, 1660–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Salahudeen, M.S.; Bereznicki, L.R.E.; Curtain, C.M. Pharmacist-Led Interventions to Reduce Adverse Drug Events in Older People Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 3672–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographics | N (n) |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 42 (10) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 234 (90.0) |

| Man | 26 (10.0) |

| Hospital Pharmacy Specialist | |

| Yes | 180 (69.2) |

| No | 80 (30.8) |

| Education Level | |

| BSc | 43 (16.5) |

| MPharm | 145 (55.8) |

| Postgraduate | 31 (11.9) |

| MSc | 34 (13.1) |

| PhD | 7 (2.7) |

| Years Working in Hospital Pharmacy | |

| ≤5 | 69 (26.5) |

| 6–10 | 52 (20.0) |

| 11–15 | 39 (15.0) |

| 16–20 | 35 (13.5) |

| 20–25 | 31 (11.9) |

| >25 | 34 (13.1) |

| Institution Type | |

| Hospital—Local Health Unit | 205 (78.8) |

| Primary Care—Local Health Unit | 4 (1.5) |

| Private Hospital | 41 (15.8) |

| Long Term Care Facilities (LTCFs) | 10 (3.8) |

| Beds Number | |

| <100 | 29 (11.2) |

| 100–250 | 47 (18.1) |

| 251–500 | 91 (37.3) |

| 501–1000 | 53 (20.4) |

| >1000 | 31 (11.9) |

| Not applicable | 3 (1.2) |

| Hospital Pharmacy Area (multiple selection allowed) | |

| Clinical Pharmacy—Inpatients | 183 (70.4) |

| Clinical Pharmacy—Outpatients | 129 (49.6) |

| Oncology | 122 (46.9) |

| Compounding | 99 (38.1) |

| Management | 95 (36.5) |

| Acquisitions | 86 (33.1) |

| Pharmaceutical Consultation | 67 (25.8) |

| Pharmacokinetics | 66 (25.4) |

| Clinical Trials | 52 (20.0) |

| Pharmacy Residency Program | 3 (1.2) |

| Other | 19 (7.3) |

| Clinical Service Assigned (multiple selection allowed) | |

| General Medicine | 32 (12.3) |

| Oncology/Haematology | 25 (9.6) |

| General Surgery | 24 (9.2) |

| ICUs | 20 (7.7) |

| Day Hospitals | 19 (7.3) |

| Paediatrics | 16 (6.2) |

| Emergency | 13 (5.0) |

| Obstetrics & Gynaecology | 11 (4.2) |

| Orthopaedics | 10 (3.8) |

| Nephrology | 9 (3.5) |

| Cardiology | 8 (3.1) |

| Infectious Diseases | 6 (2.3) |

| Neurology | 6 (2.3) |

| Operating Room | 6 (2.3) |

| Other | 48 (18.5) |

| Not assigned to any particular service | 26 (10) |

| Not applicable | 74 (28.5) |

| N (n) | |

|---|---|

| PI Documentation Methods | |

| Microsoft Excel | 111 (42.7) |

| CPOE | 97 (37.3) |

| EHR | 69 (26.5) |

| Google Forms | 28 (10.8) |

| Paper | 29 (11.2) |

| Microsoft Access | 24 (9.2) |

| Other | 30 (11.5) |

| PIs are NOT recorded | 18 (6.9) |

| PI Classification Methods | |

| In-house developed classification | 108 (41.5) |

| Validated Classification | 7 (2.7) |

| 1 (0.4) |

| 1 (0.4) |

| 1 (0.4) |

| 4 (1.5) |

| PIs are NOT classified | 145 (55.8) |

| Level of Agreement n (%) | Level of Disagreement n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Items | |||

| 253 (97.3) | 7 (2.7) | |

| 238 (91.5) | 22 (8.5) | |

| 245 (94.5) | 15 (5.8) | |

| 248 (95.4) | 12 (4.6) | |

| 224 (86.2) | 36 (13.8) | |

| 138 (53.1) | 122 (46.9) | |

| Affective Items | |||

| Process |

| 242 (93.1) | 18 (6.9) |

| 202 (77.7) | 59 (22.3) | |

| 239 (91.9) | 21 (8.1) | |

| 250 (96.2) | 10 (3.8) | |

| Outcome |

| 260 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| 253 (97.3) | 7 (2.7) | |

| 251 (96.5) | 9 (3.5) | |

| Satisfaction |

| 61 (23.5) | 199 (76.5) |

| 38 (14.6) | 222 (85.4) |

| Factor | Item | SRW | URW | SE | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | PRO1 | 0.648 | 1.000 | – | |

| PRO2 | 0.693 | 1.408 | 0.151 | ||

| PRO3 | 0.711 | 1.074 | 0.113 | ||

| PRO4 | 0.823 | 1.154 | 0.109 | 0.52 | |

| Outcome | OUT1 | 0.406 | 1.000 | – | |

| OUT2 | 0.814 | 2.995 | 0.493 | ||

| OUT3 | 0.402 | 1.653 | 0.359 | 0.33 | |

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | 2.706 † | 1.000 | – | |

| SAT2 | 0.293 | 0.100 | 0.672 | n.a. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Machado, S.; Falcão, F.; Cavaco, A.M. Hospital Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions: A Nationwide Validation Study in Portugal. Pharmacy 2025, 13, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060159

Machado S, Falcão F, Cavaco AM. Hospital Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions: A Nationwide Validation Study in Portugal. Pharmacy. 2025; 13(6):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060159

Chicago/Turabian StyleMachado, Sara, Fátima Falcão, and Afonso Miguel Cavaco. 2025. "Hospital Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions: A Nationwide Validation Study in Portugal" Pharmacy 13, no. 6: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060159

APA StyleMachado, S., Falcão, F., & Cavaco, A. M. (2025). Hospital Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Documenting and Classifying Pharmaceutical Interventions: A Nationwide Validation Study in Portugal. Pharmacy, 13(6), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13060159