Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

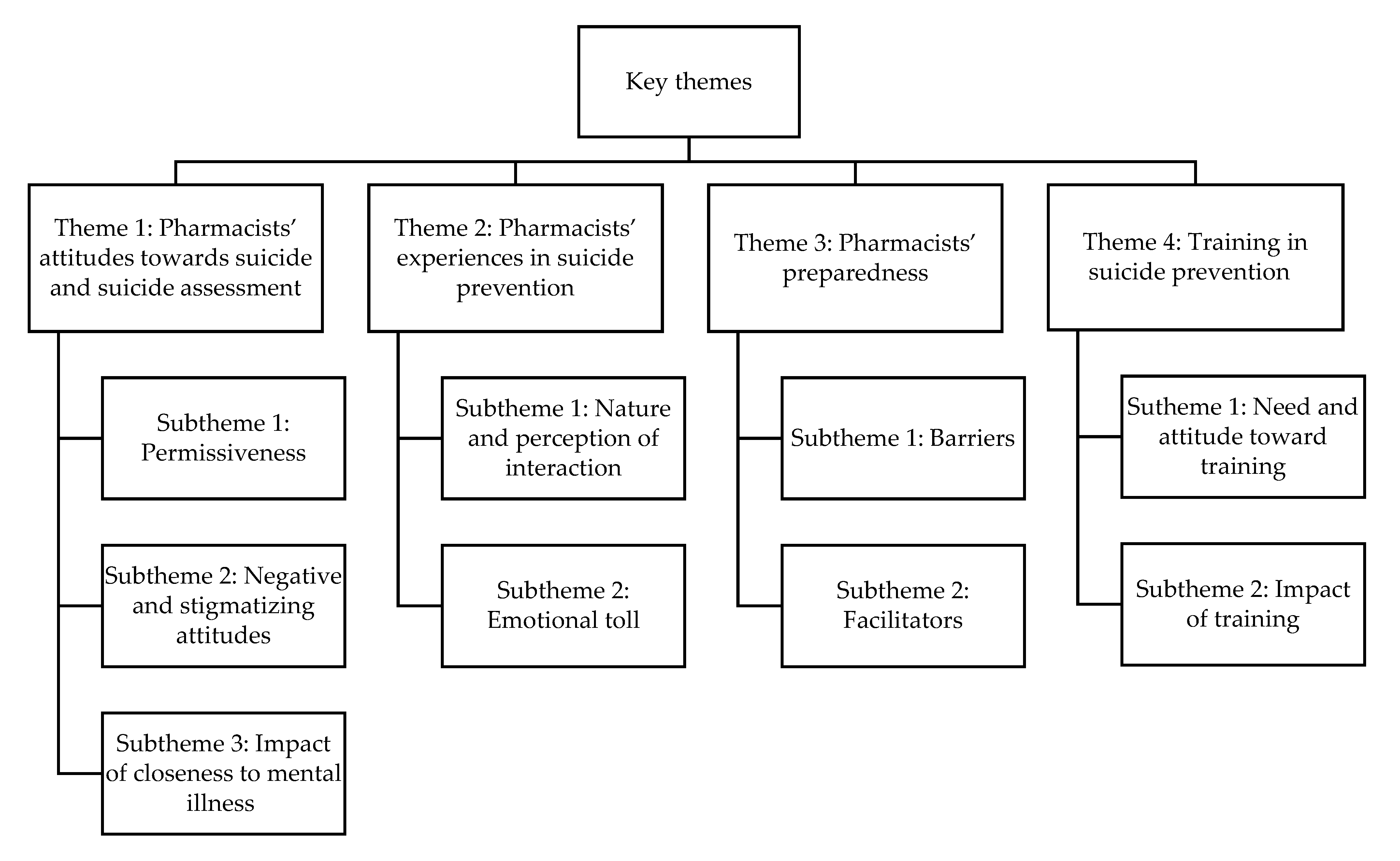

3. Results

3.1. Study Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Key Findings

| Author; Year of Publication; Country a | Objectives b | Study Design and Instruments Used | Number (n) of Pharmacists; Practice Setting; Practice Location j | Study Population Characteristics (Gender, Age) k | Personal Experience # and Suicide Training | Summary of Results |

| Kodaka M et al.; 2013; Japan [41] | Explore attitudes of pharmacists participating in BCPP Specialist seminar towards suicide and its association with demographic, occupational, and personal factors | Survey

|

|

|

|

|

| Coppens E et al.; 2014; Germany, Hungary, Ireland, and Portugal [40] | Improve CFs’ attitudes towards depression, knowledge of suicide, and confidence to detect suicidal behaviour; identify training needs | Single-group pre-and post-test evaluation

|

|

|

| |

| Murphy AL et al.; 2017 Australia and Canada [30] | Determine pharmacists’ attitudes to suicide | Survey

|

|

|

|

|

| Cates M et al.; 2017; US [34] | Determine if continuing education (CPE) on suicide prevention can positively affect pharmacists’ attitudes towards suicide prevention | Knowledge-based CPE activity with pre- and post-training surveys

|

| The mean total ASP score decreased from M = 33.1 (±SD 4.3) to M = 30.0 (±SD 6.6) (p < 0.001) indicating more positive attitudes towards suicide prevention after the educational activity Pharmacists will practice differently after CPE by: Having more awareness of suicide warnings Be more willing to assess people at risk of suicide Be more open to counselling and communicating with people at risk of suicide

| ||

| Painter N et al.; 2018; US [35] | Examine the effect of suicide prevention training program on participant’s perception, self-efficacy, and attitude towards suicide prevention | Question, Persuade, and Refer (QPR) Gatekeeper TrainingProgram and pre- and post-training surveys

|

|

|

|

|

| Murphy AL et al.; 2018; Australia and Canada [31] | Explore the practice experiences of Canadian and Australian community pharmacists’ in caring for people at risk of suicide | Thematic analysis of open-ended comments |

|

|

| |

| Murphy AL et al.; 2019; Australia and Canada [32] | Examine Canadian and Australian community pharmacists’ experiences with people at risk of suicide | Online survey |

|

|

|

|

| Murphy AL et al.; 2019; Australia and Canada [26] | Measure community pharmacists’ stigma of suicide | Survey

|

|

|

|

|

| Gorton H et al.; 2019; UK [39] | Explore current and potential role of community pharmacy teams in self-harm and suicide prevention | One-on-one semi-structured interviews |

|

|

| |

| Cates M et al.; 2019; US [38] | Determine pharmacists’ attitudes, interests, and perceived skills in suicide prevention | Survey

|

|

|

| More disagreement (29%) vs. agreement (25%) in interest in being directly involved in suicide prevention (e.g., screening or counselling at-risk patients) <50% agreed they have an interest in being indirectly involved in suicide prevention (e.g., distributing patient literature) 56% agreed they had an interest in receiving training in suicide prevention The ASP Scale: 90% reported they lack the necessary training >50% disagreed to feeling comfortable about asking patients direct, open questions on suicide Item “I resent being asked to do more about suicide” had an M = 1.8 (±SD 0.63), which indicated a positive attitude towards suicide prevention Items “It is easy for people not involved in clinical practice to make judgments about suicide prevention” and “I don’t feel comfortable assessing someone for suicide risk” had means of M = 3.28 (±SD 0.9), M = 3.11 (±SD 0.97), which indicated more negative attitudes towards suicide prevention. Inverse correlation found between ASP scores and participants’ interests in direct involvement in suicide prevention, indirect involvement in suicide prevention, and receiving training in suicide prevention (p < 0.001) * Perceived skills in suicide prevention had statistically significant correlations with interest in being directly involved in suicide prevention (p < 0.05) |

| Carpenter D et al.; 2020; US [36] | Develop and evaluate a measure to assess the frequency that pharmacy staff meet suicide at-risk patients; describe their interactions in suicide prevention and training preferences. | survey

|

|

|

| |

| Gillette C et al.; 2020; US [37] | Investigate community pharmacists’ attitudes towards suicide; identify pharmacist-reported barriers to suicidal assessment; evaluate facilitators and barriers to pharmacists conducting suicidal assessments | Online survey

|

|

|

|

|

| El-Den S et al.; 2022; Australia and Canada [33] | Explore the impact of providing suicide care on pharmacists and the support needed | Online survey

|

|

|

| 62% were encouraged by their experience in suicide care to upskill in mental crisis care 72% felt training in mental health crisis management was very important for community pharmacists 54% directly acknowledged/discussed the issue of suicide with patients More likely to report negative effects if previously interacted with patients at risk of suicide (p = 0.001) Factors that encouraged upskilling in mental healthcare (all p < 0.05): previous training previous interaction with patients at risk of suicide personal diagnosis with mental illness having a close contact who had attempted or died by suicide

|

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- ▪

- Databases used:

- -

- PubMed;

- -

- EMBASE;

- -

- Cochrane Central registration of controlled trials;

- -

- Cochrane Database of systemic reviews;

- -

- PsycINFO;

- -

- CINAHL.

- ▪

- Other sources:

- -

- Google;

- -

- Gray literature;

- -

- BASE;

- -

- EASY;

- -

- DuchDuchGo;

- -

- Arxiv.

- ▪

- Inclusion criteria

- -

- Studies that reported pharmacists’ experiences, attitudes, or trainings in suicide prevention and management.

- -

- Studies that involved pharmacists’ interactions with patients who have signs or risk factors for suicide.

- ▪

- Exclusion criteria

- -

- Studies not published in English;

- -

- Reviews, systemic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses, in vitro or in vivo studies, studies on animals;

- -

- Conference abstracts, proceedings, reports, letters to the editor, comments;

- -

- Studies where full text and/or abstract were not available;

- -

- Papers reporting only pharmacy students’ experience in suicide prevention programs;

- -

- Papers reporting on multiple health care professionals, where pharmacists’ data could not be extracted separately;

- -

- Studies examining pharmacists’ perspectives on dispensing medications with risk of misuse or being used in suicide;

- -

- Studies focused on pharmacists’ trainings and roles in mental illnesses not related to suicide.

- ▪

- Search terms:To obtain the final search terms, we used Mesh PubMed, looked at keywords from related articles, and consulted a librarian and researcher.

- (People): Pharmacist*;

- (Outcome): Suicide OR suicide prevention; OR suicide control OR self-killing OR self-harm OR Suicide* Ideation OR Suicide, Attempted; OR completed suicide OR suicide education OR suicide program OR suicide management OR suicide training OR suicidal;

- (Comparison/behaviour): attitudes OR clinical skills OR knowledge OR experience OR perceptions OR thoughts OR feedback OR opinion* OR sentiment* OR belief OR background OR interaction OR willingness OR confidence OR competent* OR readiness OR behaviour* OR behaviour* OR barrier OR challenge OR benefit OR ability* OR accept*.

- ▪

- Strategy:

- Search A;

- Search B;

- Search C;

- Combine A and B and C;

- Remove duplicates;

- Exclude reviews, scoping reviews;

- Screen titles and abstracts for papers about pharmacists’ perception, willingness, and attitude towards suicide prevention.

References

- WHO. Suicide. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Cerel, J.; Brown, M.M.; Maple, M.; Singleton, M.; van de Venne, J.; Moore, M.; Flaherty, C. How Many People Are Exposed to Suicide? Not Six. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.; Miller, G.F.; Barnett, S.B.L.; Florence, C. Economic Cost of Injury—United States 2019. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1655–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmedani, B.K.; Simon, G.E.; Stewart, C.; Beck, A.; Waitzfelder, B.E.; Rossom, R.; Lynch, F.; Owen-Smith, A.; Hunkeler, E.M.; Whiteside, U.; et al. Health Care Contacts in the Year Before Suicide Death. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Martin, C.E.; Pearson, J.L. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzinga, E.; de Kruif, A.; de Beurs, D.P.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Franx, G.; Gilissen, R. Engaging primary care professionals in suicide prevention: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukouvalas, E.; El-Den, S.; Murphy, A.L.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; O’Reilly, C.L. Exploring Health Care Professionals’ Knowledge of, Attitudes Towards, and Confidence in Caring for People at Risk of Suicide: A Systematic Review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, S1–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Gaynes, B.; Burda, B.U.; Williams, C.; Whitlock, E.P. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. In Screening for Suicide Risk in Primary Care: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Obando Medina, C.; Kullgren, G.; Dahlblom, K. A qualitative study on primary health care professionals’ perceptions of mental health, suicidal problems and help-seeking among young people in Nicaragua. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wärdig, R.E.; Hultsjö, S.; Lind, M.; Klavebäck, I. Nurses’ Experiences of Suicide Prevention in Primary Health Care (PHC)—A Qualitative Interview Study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.S.; Marcon, S.R.; Nespollo, A.M.; Santos, H.; Espinosa, M.M.; Oliveira, K.K.B.; Lima, J. Attitudes of health professionals towards suicidal behavior: An intervention study. Rev. Saude Publica 2022, 56, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.L.; Hillier, K.; Ataya, R.; Thabet, P.; Whelan, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Gardner, D. A scoping review of community pharmacists and patients at risk of suicide. Can. Pharm. J. 2017, 150, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenbrok, L.A.; Tang, S.; Gabriel, N.; Guo, J.; Sharareh, N.; Patel, N.; Dickson, S.; Hernandez, I. Access to community pharmacies: A nationwide geographic information systems cross-sectional analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1816–1822.e1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. About Community Pharmacy. Available online: https://psnc.org.uk/psncs-work/about-community-pharmacy/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- The Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Vital Facts on Community Pharmacy; The Pharmacy Guild of Australia: Barton, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eades, C.E.; Ferguson, J.S.; O’Carroll, R.E. Public health in community pharmacy: A systematic review of pharmacist and consumer views. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, H.C.; O’Reilly, C.; Berry, H.J.; Gardner, D.; Murphy, A. Understanding pharmacy staff attitudes and experience relating to suicide. In Pharmacy Practice Research Case Studies; Babar, Z.-U.-D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Chapter 6; pp. 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Beth Manders, J.K. Suicides in the UK: 2018 Registrations. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2018registrations#suicide-methods (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Han, J.; Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L.; Randall, R. Factors Influencing Professional Help-Seeking for Suicidality. Crisis 2018, 39, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, S.; Caley, C.F. Supporting patients with mental illness: Deconstructing barriers to community pharmacist access. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, O.; van Hout, H.; Nieuwenhuyse, H.; Heerdink, E. Impact of coaching by community pharmacists on drug attitude of depressive primary care patients and acceptability to patients; a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moose, J.; Branham, A. Pharmacists as Influencers of Patient Adherence. Pharm. Times Oncol. Ed. 2014, 21. Available online: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacists-as-influencers-of-patient-adherence (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Mey, A.; Knox, K.; Kelly, F.; Davey, A.K.; Fowler, J.; Hattingh, L.; Fejzic, J.; McConnell, D.; Wheeler, A.J. Trust and Safe Spaces: Mental Health Consumers’ and Carers’ Relationships with Community Pharmacy Staff. Patient—Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2013, 6, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, A.; McKee, J.; Hughes, C.; Pfeiffenberger, T. Community pharmacists’ attitudes toward providing care and services to patients with severe and persistent mental illness. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, S217–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.L.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Ataya, R.; Doucette, S.P.; Martin-Misener, R.; Rosen, A.; Gardner, D.M. A survey of Canadian and Australian pharmacists’ stigma of suicide. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312118820344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A.L.; O’Reilly, C.; Martin-Misener, R.; Ataya, R.; Gardner, D. Community pharmacists’ attitudes on suicide: A preliminary analysis with implications for medical assistance in dying. Can. Pharm. J. 2017, 151, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.L.; Ataya, R.; Himmelman, D.; O’Reilly, C.; Rosen, A.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Martin-Misener, R.; Burge, F.; Kutcher, S.; Gardner, D.M. Community pharmacists’ experiences and people at risk of suicide in Canada and Australia: A thematic analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. Int. J. Res. Soc. Genet. Epidemiol. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 53, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.L.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Ataya, R.; Doucette, S.P.; Burge, F.I.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Chen, T.F.; Himmelman, D.; Kutcher, S.; Martin-Misener, R.; et al. Survey of Australian and Canadian Community Pharmacists’ Experiences With Patients at Risk of Suicide. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 71, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Den, S.; Choong, H.J.; Moles, R.J.; Murphy, A.; Gardner, D.; Rosen, A.; O’Reilly, C.L. Exploring the impact of suicide care experiences and post-intervention supports sought among community pharmacists: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacy. 2022, 44, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cates, M.E.; Thomas, A.C.; Hughes, P.J.; Woolley, T.W. Effects of focused continuing pharmacy education on pharmacists’ attitudes toward suicide prevention. Pharm. Educ. 2017, 17, 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, N.A.; Kuo, G.M.; Collins, S.P.; Palomino, Y.L.; Lee, K.C. Pharmacist training in suicide prevention. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, D.M.; Lavigne, J.E.; Colmenares, E.W.; Falbo, K.; Mosley, S.L. Community pharmacy staff interactions with patients who have risk factors or warning signs of suicide. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillette, C.; Mospan, C.M.; Benfield, M. North Carolina community pharmacists’ attitudes about suicide and willingness to conduct suicidal ideation assessment: A cross-sectional survey study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 727–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cates, M.E.; Hodges, J.R.C.; Woolley, T.W. Pharmacists’ attitudes, interest, and perceived skills regarding suicide prevention. Ment. Health Clin. 2019, 9, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, H.C.; Littlewood, D.; Lotfallah, C.; Spreadbury, M.; Wong, K.L.; Gooding, P.; Ashcroft, D.M. Current and potential contributions of community pharmacy teams to self-harm and suicide prevention: A qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, E.; Van Audenhove, C.; Iddi, S.; Arensman, E.; Gottlebe, K.; Koburger, N.; Coffey, C.; Gusmão, R.; Quintão, S.; Costa, S.; et al. Effectiveness of community facilitator training in improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in relation to depression and suicidal behavior: Results of the OSPI-Europe intervention in four European countries. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 165, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaka, M.; Inagaki, M.; Yamada, M. Factors associated with attitudes toward suicide: Among Japanese pharmacists participating in the Board Certified Psychiatric Pharmacy Specialist Seminar. Crisis 2013, 34, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witry, M.; Karamese, H.; Pudlo, A. Evaluation of participant reluctance, confidence, and self-reported behaviors since being trained in a pharmacy Mental Health First Aid initiative. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remote. COBUILD Advanced English Dictionary; HarperCollins: Glasgow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lauber, C.; Rössler, W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2007, 19, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, A.N.; Lavigne, J.E.; Carpenter, D.M. A Scoping Review of Suicide Prevention Training Programs for Pharmacists and Student Pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassir, H.; Eaton, H.; Ferguson, M.; Procter, N.G. Role of the pharmacist in suicide prevention: Primely positioned to intervene. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2019, 49, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.L.; Gardner, D.M.; Chen, T.F.; O’Reilly, C.; Kutcher, S.P. Community pharmacists and the assessment and management of suicide risk. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. Des Pharm. Du Can. 2015, 148, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberté, M.-C.; Perreault, S.; Damestoy, N.; Lalonde, L. Ideal and actual involvement of community pharmacists in health promotion and prevention: A cross-sectional study in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chike-Obuekwe, S.; Gray, N.J.; Gorton, H.C. Suicide Prevention in Nigeria: Can Community Pharmacists Have a Role? Pharmacy 2022, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamal, L.; Jacob, S.A. Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010025

Kamal L, Jacob SA. Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy. 2023; 11(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamal, Lujain, and Sabrina Anne Jacob. 2023. "Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review" Pharmacy 11, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010025

APA StyleKamal, L., & Jacob, S. A. (2023). Pharmacists’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes towards Suicide and Suicide Prevention: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy, 11(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11010025