Perceptions of Pharmacy Students on the E-Learning Strategies Adopted during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Previously Identified Systematic Reviews on the Same and/or Similar Topics

2.2. Concepts and Definitions

2.3. Responsible for the Collection and Analysis of Selected Papers

2.4. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and PICOS

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Screened Databases and Timeframe

2.7. Keywords

3. Results

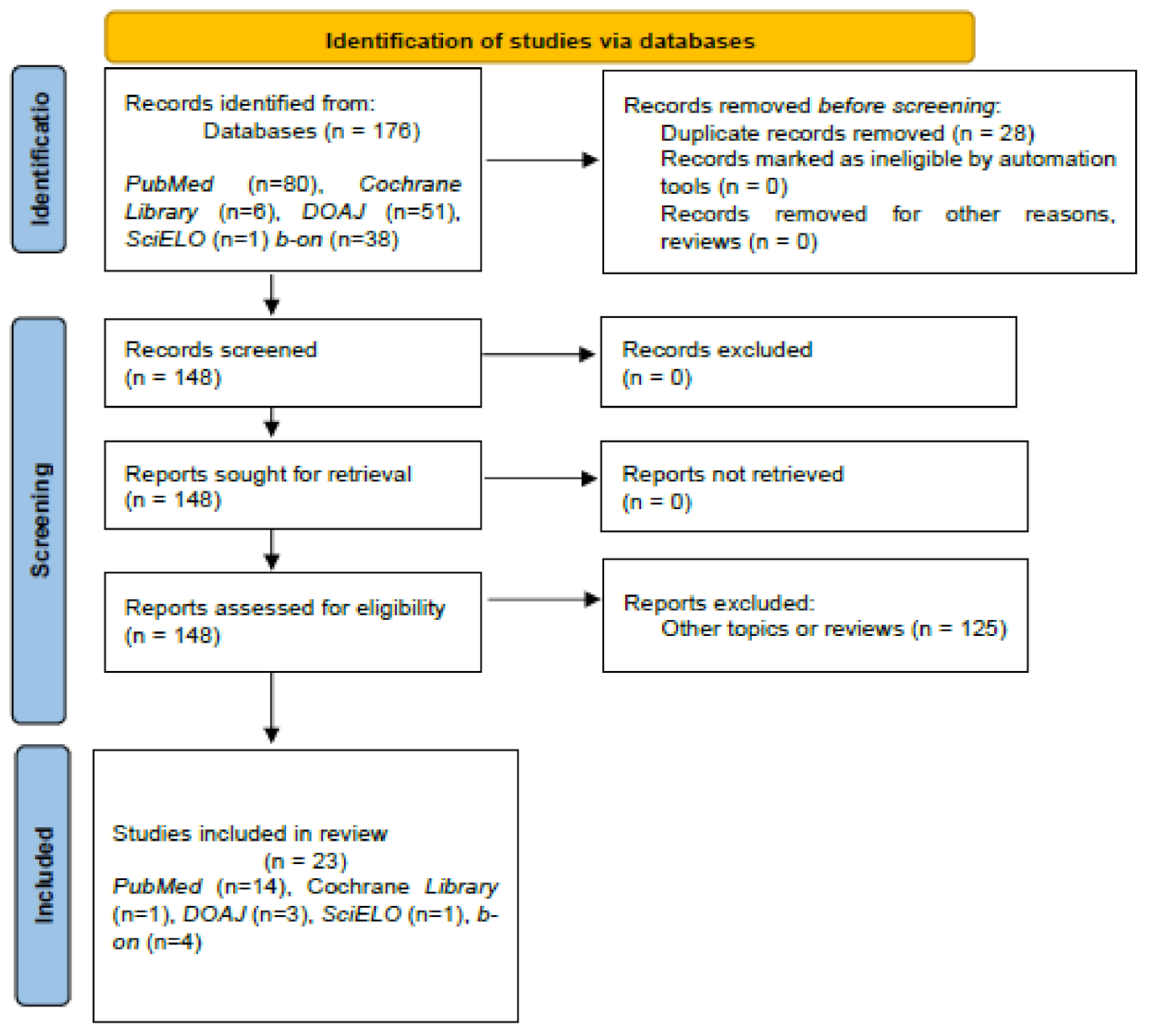

3.1. Selected Studies

3.2. Main Findings of Selected Studies

- Studies exclusively involving pharmacy students (n = 8);

- Studies simultaneously involving pharmacy students and other healthcare students (n = 6); and

- Studies related to the involvement of pharmacy students in specific courses/ activities (n = 9).

3.2.1. Studies Exclusively Involving Pharmacy Students

3.2.2. Studies Simultaneously Involving Pharmacy Students and Other Healthcare Students

3.2.3. Studies Related to the Involvement of Pharmacy Students in Specific Courses/Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. Studies Exclusively Involving Pharmacy Students

4.2. Studies Simultaneously Involving Pharmacy Students and Other Healthcare Students

4.3. Studies Related to the Involvement of Pharmacy Students in Specific Courses/Activities

4.4. Limitations of the Selected Studies, Practical Implications and Future Research

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almetwazi, M.; Alzoman, N.; Al-Massarani, S.; Alshamsan, A. COVID-19 impact on pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and opportunities. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2020, 28, 1431–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naciri, A.; Radid, M.; Kharbach, A.; Chemsi, G. E-learning in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojan, J.; Haas, M.; Thammasitboon, S.; Lander, L.; Evans, S.; Pawlik, C.; Pawilkowska, T.; Lew, M.; Khamees, D.; Peterson, W.; et al. Online learning developments in undergraduate medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 69. Med. Teach. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Santos, C.; Coutinho, A.; Cruz-Correia, R.; Ferreira, A.; Costa-Pereira, A. E-learning at Porto Faculty of Medicine. A case study for the subject ‘Introduction to Medicine’. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2007, 129 Pt 2, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Tagg, P.I.; Arreola, R.A. Earning a Master’s of Science in Nursing through distance education. J. Prof. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Coll. Nurs. 1996, 12, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaem, M.H.; Akkawi, M.E.; Nazar, N.; Ab Rahman, N.S.; Mohamed, M. Malaysian pharmacy students’ perspectives on the virtual objective structured clinical examination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Alami, Z.M.; Adwan, S.W.; Alsous, M. Remote Learning During COVID-19 Lockdown: A Study on Anatomy and Histology Education for Pharmacy Students in Jordan. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2021, ase.2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, K.; Javed, K.; Arooj, M.; Sethi, A. Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2020, 36, S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzych, G.; Schraen-Maschke, S. Interactive pedagogical tools could be helpful for medical education continuity during COVID-19 outbreak. Ann. De Biol. Clin. 2020, 78, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.A.A.; Wijesuriya, D.I.; Ekanayake, S.Y.; Rennie, A.E.W.; Lambert, C.G.; Gunawardhana, N. Online Delivery of Teaching and Laboratory Practices: Continuity of University Programmes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernasev, A.; Desai, M.; Jonkman, L.J.; Connor, S.E.; Ware, N.; Sekar, M.C.; Schommer, J.C. Student Pharmacists during the Pandemic: Development of a COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (COVKAP) Survey. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Ochoa, J.J.; Lopez-Aliaga, I.; Alferez, M.; Gomez-Guzman, M.; Lopez-Ortega, S.; Diaz-Castro, J. Lockdown. Emotional Intelligence, Academic Engagement and Burnout in Pharmacy Students during the Quarantine. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2020, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witze, A. Universities will never be the same after the coronavirus crisis. Nature 2020, 582, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinall, R.; Balan, P. Use of Concept Mapping to Identify Expectations of Pharmacy Students Selecting Elective Courses. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine. PubMed. Gov. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- SciELO. Scientific Electronic Library Online. Available online: https://scielo.org/en/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- b-on. Online Library of Knowldge. [Biblioteca do conhecimento online]. Available online: https://www.b-on.pt/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- DOAJ. Directory of Open Access Journals. Available online: https://doaj.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Cochrane Library. Cochrane Library website. Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/about-us (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Definition of perception. 2022. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/perception?q=perception (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Definition of satisfaction. 2022. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/satisfaction?q=satisfaction (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Definition of attitude. 2022. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/attitude?q=attitude (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Definition of opinion. 2022. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/opinion?q=opinion (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) website: PRISMA checklist and flow diagram. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James Cook University Australia. Systematic Reviews. Available online: https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/systematic-review/keywords (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Alghamdi, S.; Ali, M. Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdown in Saudi Arabia. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurshi, A. Investigating the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on pharmaceutical education in Saudi Arabia—A call for a remote teaching contingency strategy. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2020, 28, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karattuthodi, M.S.; Chandran, C.S.; Thorakkattil, S.A.; Chandrasekhar, D.; Poonkuzhi, N.P.; Ageeli, M.M.; Madathil, H. Pharmacy Student’s challenges in virtual learning system during the second COVID 19 wave in southern India. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2022, 5, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, G.M.M.; Matos, R.C.; Sousa, M.C.V.B.; Gomes, M.A.; Custódio, F.B.; Soares, C.D.V.; Pereira, E.A.J.; Lucas Mota, A.P.; Gonzaga no Nascimento, M.M.; Ruas, C.M. Assessment of satisfaction in emergency remote teaching from the student perspective. Preprint 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawaqfeh, M.S.; Al Bekairy, A.M.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Alkatheri, A.A.; Qandil, A.M.; Obaidat, A.A.; Al Harbi, S.; Muflih, S.M. Pharmacy Students Perceptions of Their Distance Online Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520963039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altwaijry, N.; Ibrahim, A.; Binsuwaidan, R.; Alnajjar, L.I.; Alsfouk, B.A.; Almutairi, R. Distance Education During COVID-19 Pandemic: A College of Pharmacy Experience. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2099–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Caliph, S.; Simpson, C.; Khoo, R.Z.; Neviles, G.; Muthumuni, S.; Lyons, K.M. Pharmacy Student Challenges and Strategies towards Initial COVID-19 Curriculum Changes. Healthc. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, D.K.; Hall, J.J.; Charrois, T.L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pharmacy students’ personal and professional learning. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavudeen, S.S.; Easwaran, V.; Mir, J.I.; Shahrani, S.M.; Aseeri, A.A.; Khan, N.A.; Almodeer, A.M.; Asiri, A.A. The influence of COVID-19 related psychological and demographic variables on the effectiveness of e-learning among health care students in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ Off. Publ. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2021, 29, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, E.Y.; Qablan, A.M.; Atrooz, F.Y.; Almomany, A.M.; Hajjo, R.M.; Almomani, H.Y. The Influence of Coronavirus Diseases 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and the Quarantine Practices on University Students’ Beliefs About the Online Learning Experience in Jordan. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 595874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Neklawy, A.F.; Ismail, A. Online anatomy team-based learning using blackboard collaborate platform during COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Anat. (New York N.Y.) 2022, 35, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasiri, N.R.; Weerakoon, B.S. Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceptions of allied health sciences undergraduates. Radiography 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosillo, N.; Montes, N. Escape Room Dual Mode Approach to Teach Maths during the COVID-19 Era. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Susamma, C. Quantitative Analysis of the Evolving Student Experience during the Transition to Online Learning: Second-Language STEM Students. J. Teach. Learn. Technol. 2021, 10, 373–385. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, P.M.; Rhein, E.; Nuffer, M.; Gleason, S.E. Educational Methods and Technological Innovations for Introductory Experiential Learning Given the Contact-Related Limitations Imposed by the SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann-Birkbeck, L.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Khan, S.A.; O’Donoghue, M.; Grant, G.D. Learner attitudes towards a virtual microbiology simulation for pharmacy student education. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann-Birkbeck, L.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Khan, S.A.; Cheesman, M.J.; O’Donoghue, M.; Grant, G.D. Can a virtual microbiology simulation be as effective as the traditional Wetlab for pharmacy student education? BMC Med Educ. 2021, 21, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.J. Online Chemistry Crossword Puzzles Prior to and during COVID-19: Light-Hearted Revision Aids That Work. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 3194–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Chau, H.V.; Heejung, B.; Meyer, L.; Islam, M.A. Performance of Pharmacy Students in a Communications Course Delivered Online During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, A.; Minshew, L.M.; Anksorus, H.N.; McLaughlin, J.E. Remote OSCE Experience: What First Year Pharmacy Students Liked, Learned, and Suggested for Future Implementations. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepp, K.; Volmer, D. Use of Face-to-Face Assessment Methods in E-Learning-An Example of an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Test. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, R. Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Topic Modeling Study. Education Sciences 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakoulis, K.; Patelarou, A.; Laliotis, A.; Wan, A.C.; Matalliotakis, M.; Tsiou, C.; Patelarou, E. Educational strategies for teaching evidence-based practice to undergraduate health students: Systematic review. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamanoudy, A.Z.; Al Fayz, F.; Hassanien, M. Adapting Blackboard-Collaborate Ultra as an Interactive Online Learning Tool during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2020, 8, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.; Nandi, N. Social Media and Medical Education in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. JMIR Med Educ. 2021, 7, e25892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, A.; Salmanizadeh, F. Bahaadinbeigy, K. Tele-pharmacy: A new opportunity for consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, S.; Li, D.; Jiang, D.; Liu, F.; Guo, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, R. The Establishment and Practice of Pharmacy Care Service Based on Internet Social Media: Telemedicine in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 707442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoular, S.; Huntsberry, A.; Patel, T.; Wettergreen, S.; Brunner, J.M. Transitioning Competency-Based Communication Assessments to the Online Platform: Examples and Student Outcomes. Pharm. (Basel Switz.) 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EQUATOR network. Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

| PICOS | Definition |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | Pharmacy students. |

| Intervention (I) | Any study that collects pharmacy students’ opinion, satisfaction, perception, or attitude on e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Comparison (C) | Both types of study, i.e., with or without a comparison/control group were included. |

| Outcome (O) | Pharmacy students’ perceptions, satisfaction, attitude and/or opinions on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Study design (S) | Any study (quantitative or qualitative) involving the collection of pharmacy students’ opinion or satisfaction or perception or attitude on e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Author, Year, Geographic Region, Database | Study Aim | Sample Size, Number of Pharmacy Students (Plus Other, If Applicable) | Methods | Findings | Discussion and Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies Exclusively Involving Pharmacy Students | |||||

| (Alghamdi et al., 2021) [29] Saudi Arabia and Egypt PubMed | To explore pharmacy students’ perceptions and assess their attitude towards online education during the lockdown. | 241 out of 312 replied | Questionnaire (response rate 77%). | Students manifested an easy access to the technology, online skills, motivation, and overall favorable acceptance for online learning and examinations. Responses: “I think I learn more in online education than in face-to-face education” (36.1 agree or strongly agree); “I prefer online education to face-to-face education” (50.3% agree or strongly agree); “I feel more comfortable participating in online course discussions than in face-to-face course discussions” (70.2% agree or strongly agree) and “Online education requires more study time than face-to-face education” (44.4% agree or strongly agree). | Students have general acceptance for online education. However, only around half of the students preferred online than face-to-face learning. |

| (Alqurshi, 2020) [30] Saudi Arabia PubMed | To investigate the effect emergency remote teaching has had on pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia, and to provide recommendations that may help set in place a contingency strategy. | 703 | Questionnaires: two Likert scales (one for students and other for teachers). | Students from half of the studied colleges (9 out of 18 colleges), in general presented a good student satisfaction, while students from six colleges ranged between satisfied and unsatisfied students, and students from three colleges included some very unsatisfied students. The most explanatory variables of students’ satisfaction were, as follows: number and type of assessments, internet connection issues, limited interactions during lectures, and difficult to concentrate during virtual classrooms. Overall, 45% of students declared lack of guidance accompanied by unfamiliar methods of assessments. Concerns on the lack of student–student and student–teacher interactions: >35% of students. | A good student satisfaction only was achieved in half of the studied colleges. Recommendations: proactive learning strategies were purposed to overcome limitations of student–student and student–teacher interactions. A guide may help students to overcome constrains with assessments. |

| (Karattuthodi et al., 2022) [31] India and Saudi Arabia DOAJ | To assess the quality of virtual education and students’ attitude and acceptance towards the new system during the second wave of COVID-19. | 482 | Questionnaire. | Among other things, students declared: after lockdown, if online classes are offered as an option, I will choose it (Strongly Disagree or Disagree or Slightly Disagree = 53.5%); I prefer regular classes due to the following reasons [To get more knowledge] (Slightly Agree, Agree or Strongly agree = 93.1%); I prefer regular classes due to the following reasons (to discuss topics in the physical presence of teacher) (Slightly Agree, Agree or Strongly agree = 96%) or I prefer regular classes due to the following reasons (to conduct research/ practical works in the laboratory.) (Slightly Agree, Agree or Strongly agree = 96.9%). | The overall attitude and acceptance from the students were not satisfactory. |

| (Mendes et al., 2021) [32] Brazil SciELO | To evaluate the satisfaction of the students studying Pharmacy with Emergency Remote Education, focusing on the learning process. | 401 | Questionnaire; 401 out of 1025 (39.1%) students replied. | Students’ satisfaction with the Emergency Remote Education was on average 3.12 (scale 1 to 5): 37.9% of students (satisfied or totally satisfied, 4 or 5). Low satisfaction, regarding the quality of practical classes (3.06): 37.4% of students (satisfied or totally satisfied, 4 or 5). | The online format seems to require some improvements, especially regarding the practical classes. Slightly less than half of the pharmacy students declared being satisfied or totally satisfied, 4 or 5. |

| (Shawaqfeh et al., 2020) [33] United Arab Emirates PubMed | To evaluate the pharmacy student distance online learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 309 | Cross-sectional survey: questionnaire to evaluate students’ preparedness, attitude, and barriers (response rate of about 75%). | Average preparedness score: 32.8 ± 7.2 (Max 45). Average attitude score: 66.8 ± 16.6 (Max 105). Average barrier score: 43.6 ± 12.0 (Max 75). Students with positive attitude regarding e-learning: 49.2%. Students who have identified barriers regarding e-learning: 34%. Preparedness and attitudes scores significantly varied between different academic years (p < 0.05), with better results for the fourth-year students. | E-Learning was related to some issues, such as lack of preparedness, recognition of barriers regarding online learning or around half of the students manifesting poor attitudes. Finalists seem to manifest more favourable attitudes. |

| (Altwaijry et al., 2021) [34] Saudi Arabia PubMed | To describe the experience of academic staff and students with distance education, during the COVID-19 pandemic, at a college of pharmacy in Saudi Arabia. | Students (n = 223) and Academic Staff (n = 38) | A mixed-method approach: (1) survey to evaluate experiences of academic staff and students and (2) a focus group discussion to explore their experiences plus a five-point Likert scale. Response rate 78%. | Most students selected the option “true for me” (online education): “The amount of interactions with instructors”; “The amount of interactions with classmates”; “The distance learning process provides a personal experience that can be compared to the experience in the classroom”; ”Comfort to conduct homework’s and assignments during distance learning” and ”Comfort to study online for a longer period”. Most students selected the option “neutral” (online education): “The quality of interaction with instructors or classmates”; “Time management during distances learning period”; and “Academic achievements satisfaction during the distance education period”. Barriers and challenges: communication compared to face to face and health issues due to long time screen (students and staff). | Overall, participants showed a positive perception about online education. However, students pointed to diverse neutral domains and challenges in online learning. |

| (Liu et al., 2021) [35] Australia DOAJ | To characterize pharmacy students’ challenges and strategies during COVID-19 curriculum changes. | First-, second-, third-, and fourth-year pharmacy students (groups of 30 or 10–12 students) * | Collection of student written reflections, followed by codification. Five coders using NVivo 12 (March–May 2020). | Most coded challenges: ‘negative emotional response’ (frustration and anxiety were frequently reported) and ‘communication barrier during virtual learning’. The total number of references (students’ citations) for challenges were 589. Benefits (number of references = 68): Having satisfying placement Experiences; Less travel commuting; More family time; and Feeling valued and helpful during the pandemic. Most coded strategies were ‘using new technology’ and ‘time management’. | The identified challenges, benefits and strategies may help researchers and/or educators on achieving an adequate e-learning guidance. Both positive and negative experiences were identified, but the number of citations for challenges were much higher than the number of citations for benefits. |

| (Nagy et al., 2021) [36] Canada PubMed | To understand how the learning of pharmacy students at the University of Alberta was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. | 53 out of 397 pharmacy students replied | Questionnaire (response rate 13%). Open-ended questions: (1) how has the COVID-19pandemic situation affected your learning; (2) from a pharmacy and pharmacy school perspective, what have you learned since the COVID-19 pandemic began; and (3) from a personal perspective, what have you learned about yourself since the COVID-19 pandemic began? | Thematic analysis, with identification of two main topic: remote learning (learning environment, knowledge transfer, knowledge retention, assessment) and mental health (appreciation, stress, extroversion, motivation). Most students have a negative perception of online learning: “most students gave an initial statement that their learning was “impacted at all levels” and that the pandemic was “detrimental to [their] education.” Among the motives of students frustration were: “it takes longer to get through material” and “it was difficult to keep track of schoolwork.” Several students: home environment “loud and distracting” which was “not conducive of productivity.” | Most students have a negative perception of online learning, with two main motives being identified (e-learning and mental health status). |

| Studies simultaneously involving pharmacy students and other healthcare students | |||||

| (Alavudeen et al., 2021) [37] Saudi Arabia PubMed | To evaluate health care students’ perception towards implementation of e-learning. | Mixture Medicine (95, 37.4%); Pharmacy (125, 49.2%); Nursing (27, 10.6%); Others (7, 2.8%) | Questionnaire (April 2020 to July 2020). | Main barriers of students’ acceptance of e-learning: accessibility, inexperience, and unpreparedness. Pharmacy students (n = 125, 100%): COVID-19 affects my social and psychological wellbeing (No, 56.8%); E-learning improved the skills (No, 14.4%); E-learning has more limitations (No, 8.8%); E-learning is the future of education (No, 56%); E-learning is effective and helpful (No, 33.6%). | Overall, there was a limited student acceptance of e-learning. Pharmacy students identified both negative (e-learning have more limitations than attendance learning and will be not the future) and positive points (improvement of skills, effectiveness, and helpfulness of e-learning), with just a little more than half of students declaring no impact on social and psychological wellbeing. |

| (Almomani et al., 2021) [38] Jordan, Canada, Houston, and United Kingdom PubMed | To study the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated quarantine on university students’ beliefs about online learning practice in Jordan. | Mixture Pharmaceutical sciences (434,74.2%), General sciences (96, 16.4%), Engineering (47, 8%), and Literacy and humanities (7, 1.2%) | Questionnaire. | Students from second to fourth years were more prepared to deal with online learning than first year students. The majority of students (803%) declared that the quality of online education decreased when compared to school education. The opinion about the quantity of online education during COVID-19 pandemic decreased for 43.8% of students. Only 48.2% of students will register in online classes in the coming future. 61.5% of students classified as not fair the evaluation process used during the quarantine. Additionally, online exams were less preferred by 68% of students when compared to the in-campus exams. | E-learning during the pandemic have negatively impacted students’ beliefs and thoughts. Students were unsatisfied with quality and quantity of materials, provision of online exams, and the evaluation process. |

| (Al-Neklawy et al., 2022) [39] Egypt and Saudi Arabia PubMed | To assess students’ recall, engagement, and satisfaction with the Blackboard (Bb) collaborate platform for online team-based learning (TBL), | Mixture 306 Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery; 53 Nursing; 25 Doctor of Pharmacy, and 11 in Medical Laboratory Sciences Program | Online survey (the response rate varied between 26% and 73% per course type). All TBL sessions were recorded. Study implementation: randomization of teams, application of individual and team readiness assurance test, case applications, discussions intra and inter-team, instructions, peer evaluation and administration of the survey. | A high satisfaction with TBL was verified for all groups of students. Mean scores varied between 3.9 and 4.9 (maximum = 5) (e.g., “online TBL helped me increase my understanding of the course material” or “online TBL helped me meet the course objectives). All replies presented a statistically significant positive difference from the neutral mid-point response (p < 0.05)). | Blackboard platform for online team-based learning sessions was a successful learning tool for all groups of students. |

| (Chandrasiri and Weerakoon, 2021) [40] Sri Lanka PubMed | To determine the perceptions of Allied Health Sciences undergraduates towards online learning during the COVID-19 outbreak. | Mixture Radiography 170 (32.8%) Nursing 129 (24.9%) Medical Laboratory Sciences 94 (18.2%) Pharmacy 75 (14.5%) Physiotherapy 50 (9.7%) | Online questionnaire (the response rate varied between 9.7% and 73.2% per course type). | Perception score: mean 20.4 (4.0) (SD); maximum 27; Positive > 18, Neutral = 18, Negative < 18). 59.7% agreed that online learning is more comfortable to communicate than conventional Learning. 48.3% manifested a negative perception in relation to the offer of practical and clinical subjects online. | Most students presented a global positive perception of e-learning. However, almost half of the students manifested neutral or negative perceptions on online e-learning, with a negative perception score, regarding the administration of practical and clinical issues online. |

| (Rosillo and Montes, 2021) [41] Spain b-on | To evaluate a gamification activity on mathematics, the Escape Room. | Mixture Course 2020–2021, HyFlex System (Pharmacy = 23; Nursing = 13) Course 2019–2020, face-to-face (Pharmacy = 20; Nursing = 9) Course 2018–2019, face-to-face (Pharmacy = 20; Nursing = 21) | Questionnaires. A dual-mode approach using HyFlex System: Students may connect in face-to-face mode, online, or a mixture of both in the Escape Room. | Communication had improved more in the seminars carried out through the “Escape Room” than in the traditional seminars: 71% students. No difficulties in using ICT, or information and communications technology: 89% students. It found to be working more with the Escape room than in the traditional way: 76% students. For both pharmacy and nursing students, the valuations were not statistically significant different between the three courses and attendance was slightly higher in the course of 2020–2021 (HyFlex System). | The classroom environment, the students’ attendance to theseminars and the motivation improved in the the HyFlex System (course 2020-2021), with similar performances to the face-to-face training (courses of 2019–2020 and 2018–2019). |

| (Simon and Susamma, 2021) [42] Sultanate of Oman DOAJ | To evaluate of the Evolving Student Experience During the Transition to Online Learning:Second-Language STEM Students. | Mixture Medicine (793), Pharmacy (279), Engineering (2180) and School of Foundation Studies (497) | Administration of a questionnaire in two phases: Phase 1—1st April 2020 (response rate 31.2%) and Phase 2—21st April 2020 (response rate 15.4%). The second phase was optimized, regarding the outputs of the Phase 1. | Mobile access over PC was preferred by students. WhatsApp was more readily accepted. Synchronous instruction engaging students were more accepted than the asynchronous ones. Overall Effectiveness of Online Teaching-Learning: phase 1 (adequate, good, and very good = 41.7%). and phase 2 (adequate, good, and very good = 71.2%). Optimizations in the second phase: (a) interactive sessions, (b) better technology, and (c) the volume of available materials for students was reduced, since students considered the online learning hard. | Students seemed to learn at a slower pace and in a different way using online options. Online learning may be optimized and adjusted to the needs of students. |

| Studies related to the involvement of pharmacy students in specific courses/ activities | |||||

| (Reynolds et al., 2021) [43] USA PubMed | To compare the effectiveness of distance-based experiential learning strategies to in-person experiential rotations, and explore student perceptions of knowledge, skills, and abilities gained through this adapted curriculum. | 6 | An in-person course to provide in-person introductory experiential practice experiences was redesigned to be provided on-line. A 28-question survey at the end of the program. The six participants were from University of Colorado’s International-Trained PharmD students. The Mann–Whitney U test was utilized (pre- and post-course completion), which is a non-parametric test suitable for small samples. | Students agreed or strongly agreed that the overall distance course, the remote health system activities (e.g., Hospital Tour, Dispensing Operations, Practice Models), and the community activities (e.g., MyDispense tasks) valuable. MyDispense is a collaborative network of academic pharmacists who have formulated cases, content, and questions in this program. Students’ outcomes between both settings (in-person vs. online) were not statistically significant different for knowledge, skills, and abilities, but improved in online activities. | The redesigned course constitutes an alternative educational modality. However, students declared that they preferred live over online activities. |

| (Al-Alami et al., 2021) [7] Jordan PubMed | To explore the effectiveness and student perspective of remote teaching of the theoretical anatomy and histology course. | 362 out 442 replied | Online-based validated questionnaire. | Around half of the students, and in some evaluated parameters slightly more, manifested positive perceptions. The less scored parameter was “the remotely-taught course contributed to a better understanding of the course content than I did before the lockdown” (40.8%). Both strengths (e.g., time flexibility) and weaknesses were identified (e.g., lack of face-to-face interaction, inadequate internet connectivity or other technical issues). | In general, pharmacy students’ perceptions regarding the effect of remote delivery of the theoretical anatomy and histology were positive, with a more restrictive output concerning the understanding of the content of the course (less than half). Some of the identified study weakness may be optimized in future training. |

| (Baumann-Birkbeck et al., 2021) [44,45] Australia and China b-on and Cochrane Libray | To evaluate pharmacy students’ attitudes toward a virtual microbiology simulation. | 39 (completed the post-VUMIE™ (virtual microbiology simulation) survey) and 20 (completed the post-wet lab survey) | Surveys, a Likert scale (pre and post -intervention) plus collection of students’ comments. Comparison between a VUMIE and a traditional wet laboratory (lab). Response rates: around 50% at initial survey and around 25% at endpoint of survey. | The scores of the Likert scale were slightly higher for VUMIE than post-wet lab (overall, score VUMIE: mean score for the common rated items: 3.8 ± 0.78 VUMIE and 3.4 ± 0.76 wet laboratory (lab)). However, more students reported a specific preference for the wet lab rather than VUMIE, regarding the collection of students’ comments. VUMIE™ produced a slightly higher post-intervention mean scores (knowledge, skills, and confidence) when compared to the post-intervention mean scores of the wetlab. | Both activities were considered interesting and engaging. Study evidence was not sufficient to suggest a complete replacement of the traditional lab experience by VUMIE. The use of VUMIE previous to traditional wet laboratory (lab) work was suggested. |

| (Pearson et al., 2020) [46] United Kingdom b-on | To explore the performance of online post-lecture chemistrycrossword puzzles as revision aids prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 132 first-year and 120 second-year | Questionnaire. An online post lecture chemistry crossword puzzles. | 80% of second-year students and just over 50% of first-year students found the crosswords helpful and would welcome more. In general, students agree with more crossword puzzles embedded within their online learning environment, with higher agreement scores for the second-year students. The three most scored online revision aids to help students were 1) instructional videos, 2) quizzes/puzzles and 3) practice questions. | Chemistry-themed online crossword puzzles were well-accepted by students, especially by the second-year students. Revision aids seems to be recommended in e-learning activities. |

| (Hussain et al., 2021) [47] USA b-on | To examine pharmacy student readiness, reception, and performance in a communications course during the COVID-19 pandemic and to compare that with the performance of students who completed the same course in person the previous year. | 2019 (n = 25) and 2020 (n = 32) | Course 2019: face-to-face (15 lectures). Course 2020: online (16 lectures). Pre-course and post-course surveys were administered (pre survey n = 31 and post survey n = 26). | Student’s performance was not statistically significant different between both cohorts. Students’ preference for online education had grown by the end of the course, while face-to-face e-learning declined. The score for “the course should continue to be offered online and indicated that their online learning experience met their expectations for the course” was clearly favourable; M = 4.38 (agree = 4 and maximum 5 = strongly agree) (SD = 0.89). Students had previous e-learning experience. | Overall, student expectations with the online communications course seem to have been met. This study support e-learning after the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| (Elnaem et al., 2021) [6] Malaysia PubMed | To investigate pharmacy students’ perceptions of various aspects of virtual objective structured clinical examinations (vOSCEs). | 231 out of 253 replied | Questionnaire. Response rate (91.3%). | Satisfied with vOSCE (53.2%). 49.7% of the students preferred to not have vOSCE in the future. The virtual OSCE was less stressful as compared to the conventional OSCE (36.8% strongly agree/agree). I feel that it would be more convenient to interact face to face with the examiners rather than a video call (53.7% strongly agree/agree). | Overall, only around half of the students were satisfied with vOSCE. vOSCE administration may need to be optimized in the future. |

| (Savage et al., 2021) [48] USA PubMed | To explore student perceptions following implementation of a three-station remote OSCE administered during spring of 2020 and utilize the feedback to develop strategies for future remote OSCE implementations. | 157 (156 replied the questionnaire). | Two OSCE stations were implemented: (1) conducting a medication history interview on Day 1 and (2) presenting a patient case to a pharmacist preceptor and providing medication education to a patient on Day 2. Three open-text prompts about the remote OSCE experience were applied, as follows: (1) “I liked…”, (2) “I learned… ”, and (3) “I suggest … ”, which were administered the day after this remote experience. All replies were coded. | In general, students described this experience as positive and “applicable to their future pharmacy practice”. Diverse themes arose from this experiment. For instance, Logistics (n = 65, 41.7%), Differences In-person Versus Remote (n = 59, 37.8%), and Skill Development (n = 43, 27.6%). Among others, students classified as positive to receive materials ahead of time, clear instructions, to stay at home comfortably, or staying on schedule. | Students’ perception about the online OSCE activity was positive. OSCE is relevant to simulate telehealth activities, which will be more disseminated in the future. Students agree with the application of OSCE in the future. |

| (Sepp et al, 2021) [49] Estonia PubMed | To compare the results of three face-to-face (2018–2019) and one electronically conducted (2021) OSCE tests, as well as students’ feedback on the content and organization of the tests. | 2018 (fourth-yearStudents: 12 (Auditorium); 2019 (fourth-year Students): 15 (Auditorium); 2019 (Assistant Pharmacists): 23 (Auditorium); 2021 (fourth-year Students): 28 (Zoom) | OSCE tests comprised diverse stations to simulate different themes (e.g., cough and sore; stuffy nose and allergy, dermatitis, etc., 3.5 min). Assessment of students at each station: establishing and ending contact; evaluation of symptoms, concomitant symptoms, comorbidities, and medications used; treatment recommendations; drug information; appropriate language use; and general health and well-being counseling. Student’s feedback was collected through a questionnaire. | Students were satisfied with the provision of OSCE test regardless of the environment (Auditorium vs. Zoom). The majority of students ranked OSCE as a “very good“ or “good“ learning method. Overall assessment of the OSCE test was not statistically significant different between face-to-face and Zoom OSCE. | The implemented zoom OSCE was feasible, effective, and students were satisfied with this practice. Overall assessment was similar between both Auditorium vs. Zoom OSCE. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pires, C. Perceptions of Pharmacy Students on the E-Learning Strategies Adopted during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10010031

Pires C. Perceptions of Pharmacy Students on the E-Learning Strategies Adopted during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy. 2022; 10(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10010031

Chicago/Turabian StylePires, Carla. 2022. "Perceptions of Pharmacy Students on the E-Learning Strategies Adopted during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review" Pharmacy 10, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10010031

APA StylePires, C. (2022). Perceptions of Pharmacy Students on the E-Learning Strategies Adopted during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy, 10(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10010031