Abstract

Globally, cervical cancer is the fourth leading cause of death among women. While overall cervical cancer rates have decreased over the last few decades, minority women continue to be disproportionately affected compared to White women. Given the paucity of theory-based interventions to promote Pap smear tests among minority women, this cross-sectional study attempts to examine the correlates of cervical cancer screening by Pap test using the Multi-theory Model (MTM) as a theoretical paradigm among minority women in the United States (U.S.). Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was done for testing the construct validity of the survey instrument. Data were analyzed through bivariate and multivariate tests. In a sample of 364 minority women, nearly 31% (n = 112) of women reported not having received a Pap test within the past three years compared to the national rate (20.8%) for all women. The MTM constructs of participatory dialogue, behavioral confidence, and changes in the physical environment explained a substantial proportion of variance (49.5%) in starting the behavior of getting Pap tests, while the constructs of emotional transformation, practice for change, and changes in the social environment, along with lack of health insurance and annual household income of less than $25,000, significantly explained the variance (73.6%) of the likelihood to sustain the Pap test behavior of getting it every three years. Among those who have had a Pap smear (n = 252), healthcare insurance, emotional transformation, practice for change, and changes in the social environment predicted nearly 83.3% of the variance in sustaining Pap smear test uptake behavior (adjusted R2 = 0.833, F = 45.254, p < 0.001). This study validates the need for health promotion interventions based on MTM to be implemented to address the disparities of lower cervical cancer screenings among minority women.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth leading cause of death in the world among women [1]. It was estimated that, worldwide, 570,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer and approximately 311,000 women died due to cervical cancer in 2018 [1]. While there has been a decrease in cervical cancer mortality in the United States (U.S.), approximately 13,800 women are diagnosed and approximately 4290 women die per year [2,3]. These rates have decreased over the past few decades, yet cervical cancer disparities in the U.S. continue to affect minority women, (i.e., women who are not of White/European heritage such as African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander, American Indian, etc.) [4].

The Papanicolaou (Pap) test is an effective cervical cancer screening tool to decrease the rates of cervical cancer [5]. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends cervical cancer screening with an HPV test alone every 5 years for everyone with a cervix from age 25 until age 65 [6]. Rates of cervical cancer screening (Pap testing) in the U.S. were 81.7% for women 21–44 years old and 79.2% from women 45–64 years old [7], but the rates of cervical cancer screening are lower for Pap testing among minorities in the U.S. and disparities still exist for African Americans, Hispanics/Latina, Asians, and American Indians compared to White women [2,3,8,9,10,11].

Cervical cancer occurs primarily in low-resource, underserved areas and is typically associated with poverty, race/ethnicity, and/or other health disparities [3,11,12,13,14]. Outside the U.S., researchers found that in Norway, immigrant women reported lower adherence to cervical cancer uptake compared to native Norwegian women [15]. Similar associations have been found among Non-European Union and European Union migrants compared to German women [16], Middle Eastern women from Asian and Middle-Eastern countries [17], and Syrian refugees in Greece [18]. West African migrant women reported lower knowledge related to the importance of cervical cancer screening [19] and in China, uptake of cervical cancer screening services in Chinese migrant workers is lower than non-migrant workers in China [20].

Two determinants of cervical cancer incidence are carcinogenic HPV infection and lack of access to cervical cancer screening [3,12]. Other possible important correlates of cervical cancer screening include lack of adequate access to preventive services and not utilizing these services (e.g., lack of transportation, fear of results, and mistrust of the health care system) [12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Interventions to increase Pap testing among minority women have had some success and, in some cases, self-sampling for HPV has performed well [28,29,30,31]. For example, a culturally tailored randomized control trial (RCT) cervical cancer screening intervention among Latinas reported that women in the intervention arm had increased Pap test screening compared to those in the control group [32]. Another culturally tailored RCT intervention among North American Chinese women reported that women in the intervention arms (i.e., community outreach or direct mail) increased Pap test screening compared to women in the control group, suggesting that culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions may increase Pap test levels [33]. Another study among African American women reported that African immigrant women reported lower knowledge of cervical cancer and lower Pap test screening rates compared to African American women [34]. Yet, more studies focusing specifically on minority women in the U.S. are needed to promote Pap testing.

Few interventions among minority women utilized health behavior theories. For example, in a review, Brevik (2020) found that four RCTs of culturally tailored intervention materials were associated with a 54% increase in Pap testing [32,35,36,37,38]. However, many of these studies did not use theory in their interventions. Those that did use theory drew from social cognitive theory, the health belief model, the transtheoretical model, the social support model, elaboration theory, or multiple theories [39,40,41,42]. In sum, there are limited studies to increase cervical cancer screening among minority women and only a few of these interventions among minority women utilized theory.

There is a need to focus on newer models, such as the fourth-generation Multi-theory Model (MTM) of health behavior, to explain correlates of cervical cancer screening among minority women in the U.S. The MTM has been used in previous health behavior studies, such as for COVID-19, sleep, HPV vaccination, mammography, and melanoma, but to date, researchers have not tested the MTM on cervical cancer screening [43,44,45,46,47,48]. The purpose of this study was to examine the correlates of cervical cancer screening by Pap test using MTM as a theoretical paradigm in U.S. minority women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Sampling

Data for this cross-sectional, descriptive, and U.S. based study were collected from 7 October to 12 October through actively managed, double-opt-in market panels recruited by the Qualtrics team. The Qualtrics utilize high-quality research panels and quota sampling to meet the specific requirements of the sample requested by researchers. Previous literature described the differences between traditional survey and market-based or commercial research panels [35]. As described by Qualtrics (more information available at https://www.qualtrics.com/research-services/online-sample/, accessed on 10 February 2022), the company uses multiple strategies (e.g., dynamic surveys in a dashboard style, app-based recruitment, or through online/mobile games and social media) to recruit eligible participants through convenience sampling. Respondents can self-select to participate in the survey if they satisfy the eligibility criteria. Given the use of multiple avenues, response rate is difficult to compute. The recruitment of the sample is based on the quota constraints and screening opted by researchers who signed a contractual agreement with Qualtrics. In addition, Qualtrics ensures the quality of data by checking for bots, duplicates, speeders, and fraudulent responses before providing a complete and high-quality dataset to the researchers. Participants could be screened out due to multiple reasons: (1) if they did not qualify for the inclusion criteria; (2) if the quota was already filled during fielding; and (3) if participants took significantly less time (less than half the median time) to complete the survey, which would indicate lack of thoughtfulness to answer the questions.

2.2. Participants’ Selection Criteria

Women belonging to racial minority groups, aged between 21 and 65 years, living in the U.S., who had the ability to understand the English language, and provided voluntary informed consent were eligible to participate in this study. If participants opted to take the survey, they were asked to answer a few screening questions without revealing the original objective of the study. This was done to prevent self-selection and response bias. Eligible participants who thoughtfully completed the survey were compensated through incentives per terms and conditions set forth by Qualtrics and its data collection partners.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The study (protocol #1804208-1) was deemed “exempt” by the institutional review board in accordance with the Federal regulatory statutes. Detailed information about study’s objective and significance was provided in an information sheet, which helped participants to make informed decisions about participating in the study. In other words, participation in this survey was completely voluntary. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

2.4. Data Integrity

Qualtrics used multiple ways, such as digital fingerprinting and ‘prevent ballot box stuffing option’, to prevent multiple responses from the same participant. No identifying information was collected during the survey and responses were anonymized to prevent the collection of IP address, location data, and contact information. Data were provided to the researchers in an encrypted file.

2.5. Survey Tool

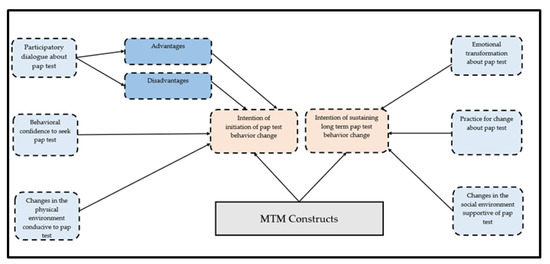

A 48-item questionnaire including 18 items related to sociodemographic factors and the remaining 30 items related to MTM constructs was developed based on the fourth-generation behavioral theory proposed by Sharma and Petosa in 2014 [36]. The MTM offered a robust approach to explain several health-related behaviors in the past [29,30,31,32,33,34]. This tool to explain the correlates of the Pap test underwent a series of iterations to check its face and content validity by a group of Subject Matter Experts (SMEs). Experts in behavioral theories, health promotion, and cancer-related research areas were randomly selected to participate in a blinded review of the tool. Their feedback and comments were addressed in a series of revisions before the final version of the tool was obtained. Once finalized, this tool was assessed for its construct validity using structural equation modelling described in detail in the methodology section. For the initiation model, except “changes in physical environment” (measured by 2 items), the subscales of perceived advantages, perceived disadvantages, and behavioral confidence (surety to overcome external and internal barriers) were measured by 5 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The “advantages” and “disadvantages” were measured on a frequency scale which included the following response options: never (0), almost never (1), sometimes (2), fairly often (3), and very often (4). Participatory dialogue was a difference derivative of “advantages” and “disadvantages”, and the score could range from −20 units to +20 units. For “change in physical environment” and “behavioral confidence”, a scale of surety was used which ranged from “not at all sure” to “completely sure.” For sustenance, “emotional transformation” and “practice for change” scales were measured on 3 items each. However, “changes in social environment” was measured through 5 items. Emotional transformation is the ability to transform emotional distress into a positive emotional state. Practice of change entails actions to maintain the behavior initiated despite the challenges and “changes in social environment” considers the role of the social support system (family and friends) to help change a particular behavior. A detailed description of the components (initiation and sustenance) of the survey is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

MTM theoretical framework for a survey tool used to explain Pap test behavior among racial minority groups.

2.6. Minimum Sample Size Calculation

Referring to the G*power 3.1.9.7 software (linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 increase), a minimal number of 154 participants was required to reach significance when considering the following statistical parameters: type I error α = 5%, power 1-β = 95%, a moderate effect size f2 = 0.15, and a total number of variables N = 15 to be integrated in the multivariable regression analysis [37,38]. Given the lack of consensus in the sample size recommendations for the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), we used Kline (2015) criteria that had 20 observations (participants) for each estimated parameter in the model, with a typical size of N = 200, among models using the maximum likelihood method [39]. However, recently, several studies recommended a sample size which would vary from 50 to 400 participants [40,41,42]. Our study sample meets the minimum requirements to yield hypothesized effects.

2.7. Data Analyses

The SPSS software v.26 (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp.) was used to conduct the descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. All assumptions were tested prior to the application of statistical models. Comparison between groups for the normally distributed numeric data was conducted using the independent samples test, whereas the chi-squared test was used to compare categorical data among groups. The Pearson correlation test was used to correlate two continuous variables. Hierarchical regression was conducted by taking initiation and sustenance scores as dependent variables. Polytomous variables used in the regression were dummy-coded. The statistical significance was denoted as p < 0.05. Missing data analysis was not warranted as a complete dataset and was obtained from Qualtrics.

The SPSS AMOS software v.24 [43] was utilized to perform the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) for testing the MTM model. All items of the main constructs of the MTM instrument were used as indicators of the latent variables of initiation and sustenance (described elsewhere in the text). A fair pair of items with similar contents were allowed correlation measurement errors. The maximum likelihood method was used for estimation. Multiple indices of goodness-of-fit were used: the relative chi-square (χ2/df; cut-off values: <2–5), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; close and acceptable fit are considered for values <0.05 and <0.11, respectively), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; acceptable values are ≥0.90) [44,45]. For each model, the overall fit, significance of structural paths, and amount of variability of the latent variables accounted for by the observed variables were assessed [39,45,46]. Standardized estimates for path coefficients, interpreted as regression coefficients, were calculated for all proposed relationships in the model. Reliability diagnostics were also performed.

3. Results

In a sample of a total of 364 participants, two hundred and fifty-two (69.2%) participants reported having the Pap smear test and nearly 31% had not had the Pap test over the past 3 years (Table 1). Among those who had a Pap smear test, the majority of the participants had it normally. The median age of both groups were comparable. The majority of the respondents from both groups were non-Hispanics, Christians, and African Americans, and had comorbidities of non-psychological in origin (Table 1). Upon comparing the socio-economic and healthcare access factors, participants who had not had a Pap smear test were less educated (5.4% vs. 0.8%; p < 0.001), uninsured (28.6% vs. 5.2%; p < 0.01), and unemployed (59.8% vs. 38.9%; p < 0.001), and had a lower income (27.7% vs. 19.8%; p = 0.004; Table 2). Among the participants with no Pap smear test, only 31.3% reported being recommended by their healthcare providers for a Pap test as opposed to the 58.3% of participants with a Pap test (Table 2). As indicated in Table 3, participants with a Pap test had higher overall initiation (3.02 ± 0.99 vs. 1.69 ± 1.41; p < 0.001) and sustenance mean scores (2.98 ± 1.06 vs. 1.50 ± 1.34; p < 0.001; Table 3) as opposed to those who had not had a Pap smear test in the past. Except for the subscale “perceived disadvantages”, the mean scores of “perceived advantages”, “participatory dialogue”, “behavioral confidence”, and “changes in physical environment” were significantly higher among participants who had a Pap smear test in the past than those who had not had a Pap smear test (Table 3). The mean scores of “perceived disadvantages” were not statistically different among both groups. For sustenance, the scores of all the subscales, namely “emotional transformation”, “practice for change”, and “changes in social environment”, were higher among participants with a Pap smear test, with statistically significant mean differences compared to the participants who had not had a Pap smear test in the past (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 364).

Table 2.

Socio-economic and healthcare access characteristics of the sample (N = 364).

Table 3.

Comparison of Multi-theory Model (MTM) constructs of participants who had Pap test and those who did not have Pap test (N = 364).

Table 4 shows the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix of all the observed variables. Perceived advantages are directly correlated with perceived disadvantages (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), behavioral confidence (r = 0.58, p < 0.01), changes in physical environment (r = 0.50, p < 0.01), emotional transformation (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), practice for change (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), and changes in social environment (r = 0.49, p < 0.01). Changes in physical environment is strongly and directly correlated with behavioral confidence (r = 0.75, p < 0.01), emotional transformation (r = 0.73, p < 0.01), and changes in social environment (r = 0.64, p < 0.01). Changes in social environment is directly correlated with practice for change (r = 0.82, p < 0.01) and emotional transformation (r = 0.78, p < 0.01, Table 4). The reliability of the entire scale was 0.94, with individual scales’ reliability ranging from 0.81 to 0.94 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pearson correlations and reliability estimates for study variables in the sample population (n = 364).

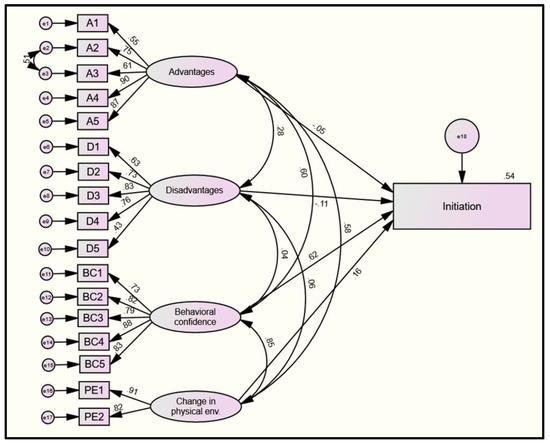

All goodness-of-fit indices suggest that the presented models (Figure 2 and Figure 3) reasonably fit the data. For the initiation model, the relative chi-square (χ2/df = 2.51; cut-off values: <2–5), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.064 (LCL 0.056; UCL 0.073); close and acceptable fit are considered for values <0.05 and <0.11, respectively), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI = 0.94), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.95; acceptable values are ≥0.90) were reasonable to indicate model fit. The estimates of each structural relationship between the MTM subscales and initiation are shown in Figure 2. Upon observing the standardized effects of latent variables on factor loadings, statistically significant effects that ranged from moderate to large were found. Except for “perceived disadvantages”, all other latent variables, including “perceived advantages” (β = 0.55 to 0.90), “behavioral confidence” (β =0.73 to 0.88), and “changes in physical environment” (β = 0.82 to 0.91), had large effects on their reflective indicators, which is suggestive of the valid measurements of the constructs used (Figure 2). Behavioral confidence had a moderate direct effect on initiating Pap smear behavior (β = 0.62, p < 0.001), whereas disadvantages had a small direct negative effect (β = −0.11, p = 0.02). Effects of advantages and change in physical activity were insignificant.

Figure 2.

Model diagram of the four-factor model of the initiation. Legend: e1–17 = error terms 1–17; A = advantages; D = disadvantages; BC = behavioral confidence; and PE = change in the physical environment. Latent variables/factors are represented with ovals. Measured/manifest variables are represented with squares. Single-headed arrows indicate a hypothesized direct relationship between two variables. Double-headed arrows demonstrate the bi-directional relationship (i.e., covariance).

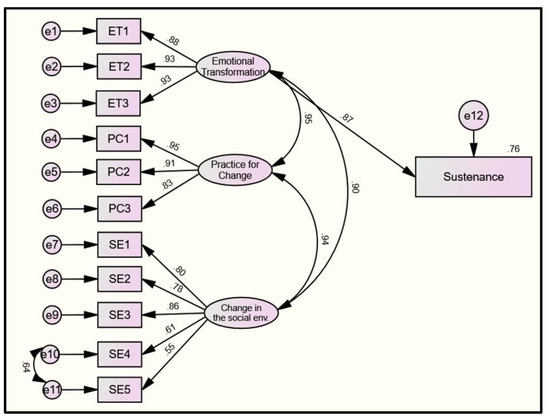

Figure 3.

Model diagram of the three-factor model of the sustenance. Legend: e1–11 = error terms 1–11; ET = emotional transformation; PC = practice for change; BC = behavioral confidence; and SE = change in the social environment. Latent variables/factors are represented with ovals. Measured/manifest variables are represented with squares. Single-headed arrows indicate a hypothesized direct relationship between two variables. Double-headed arrows demonstrate the bi-directional relationship (i.e., covariance).

Similarly, for the sustenance model, the relative chi-square (χ2/df = 2.44), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.063 (LCL 0.049; UCL 0.077)), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI = 0.97), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.98) were calculated. The estimates of each structural relationship between the MTM subscales and sustenance are shown in Figure 3. All latent variables, including “emotional transformation” (β = 0.88 to 0.93), “practice for change” (β = 0.83 to 0.95), and “changes in social environment” (β = 0.55 to 0.86), had moderate–large effects on their reflective indicators, which is suggestive of the valid measurements of the constructs used (Figure 3). Emotional transformation had a large direct effect on the sustenance of Pap smear behavior (β = 0.87, p < 0.001), as shown Figure 3.

In a multilevel regression model of initiation, Model 4 (final model) predicted nearly 50% of the variance in initiating Pap smear test uptake behavior among participants who had not had it over the past 3 years (adjusted R2 = 0.495, F = 30.66, p < 0.001, Table 5). With each unit increment in the subscales of initiation (i.e., participatory dialogue, behavior confidence, and changes in physical environment), the conditional mean for initiating Pap smear uptake behavior increased by 0.021, 0.117, and 0.106 units, respectively (Model 4, Table 5). None of the slopes of socio-economic and healthcare access variables were significant, which indicates no significant differences in the conditional mean changes in initiating Pap smear test uptake behavior among participants who had not had this test done over the past 3 years.

Table 5.

Multilevel modelling to predict likelihood for initiation of Pap test behavior among participants who had not had the Pap test over the past 3 years (n = 112).

In a multilevel regression model of sustenance, Model 4 (final model) predicted nearly 74% of the variance in initiating Pap smear test uptake behavior among participants who had not had it before (adjusted R2 = 0.736, F = 85.338, p < 0.001, Table 6). With each unit increment in the subscales of sustenance (i.e., emotional transformation, practice for change, and changes in social environment), the conditional mean for sustaining Pap smear uptake behavior increased by 0.184, 0.097, and 0.032 units, respectively (Model 4, Table 6). Except for healthcare insurance and lower income, none of the slopes of socio-economic and healthcare access variables were significant, which indicates no significant differences in the conditional mean changes in the sustenance of Pap smear test uptake behavior among participants who had not had this test done over the past 3 years.

Table 6.

Multilevel modelling to predict likelihood for sustenance of Pap test behavior among participants who had not had the Pap test over the past 3 years (n = 112).

In a multilevel regression model of sustenance among those who had a Pap smear (n = 252), Model 4 (final model) predicted nearly 83.3% of the variance in sustaining Pap smear test uptake behavior (adjusted R2 = 0.833, F = 45.254, p < 0.001, Table 7). With each unit increment in the subscales of sustenance (i.e., emotional transformation, practice for change, and changes in social environment), the conditional mean for sustaining Pap smear uptake behavior increased by 0.168, 0.111, and 0.032 units, respectively (Model 4, Table 7). Except for healthcare insurance, none of the slopes of socio-economic and healthcare access variables were significant, which indicates no significant differences in the conditional mean changes in the sustenance of Pap smear test uptake behavior among participants who had this test done over the past 3 years.

Table 7.

Multilevel modelling to predict likelihood for sustenance of Pap test behavior among participants who had the Pap test over the past 3 years (n = 252).

4. Discussion

The study aimed to utilize the contemporary Multi-theory Model (MTM) of health behavior change to explain the determinants of cervical cancer in minority women in the U.S. In our sample, 30.8% of the minority women had not received a Pap test within the past three years, which is much higher than the national statistics for all women of 20.8% [7,24]. This finding points at the continued disparities for Pap test screening among minority women in comparison to their White counterparts.

In our study, all three constructs of MTM, namely participatory dialogue (advantages of getting cervical cancer screening outweighing the disadvantages), behavioral confidence (futuristic surety emanating from self, powerful others, Almighty, etc.), and changes in the physical environment (support from the surroundings), were significantly associated with the intent to initiate cervical cancer screening among women who had not received a Pap test over the past three years and together they accounted for 49.5% of the variance in explaining the dependent variable. This is a substantial proportion of the variance in behavioral and social sciences [49]. Likewise, all three constructs of MTM, namely emotional transformation (directing emotions into goals), practice for change (persistent reflection on behavior change), and changes in the social environment (support from family, friends, etc.), as well as lack of health insurance and annual household income less of than $25,000, significantly explained 73.6% of the variance in the likelihood to sustain the Pap test behavior of getting it every three years.

The results of our study align with the previous literature as well as they provide newer insights into the correlates for developing interventions to promote cervical cancer screening through Pap tests. The finding in this study that poverty (annual household income of less than $25,000) and lack of insurance are barriers to cervical cancer screening among minority women is supported by the previous literature [12,13,14,24,26]. Structural policy efforts must be undertaken to address these root causes.

Our study found that educational tools, such as motivation through participatory dialogue, in which advantages of getting a Pap test and building the behavioral confidence of minority women are attributed, when coupled with changes in the physical environment, such as availability and accessibility of Pap test, can contribute substantially to women’s ability to start getting the Pap test at regularly prescribed intervals. The concepts of value expectancy and self-efficacy, which are similar to participatory dialogue and behavioral confidence with subtle differences, have been used in the past for promoting cervical cancer screening among Hispanic American women [41,42]. The MTM constructs should be the foundational pillars of educational interventions. The advantages of getting a Pap test, such as early detection, having peace of mind for self and family, getting early treatment, and reduction in mortality due to cervical cancer, need to be underscored through educational interventions. The feelings of anxiety, physical discomfort/pain, invasion of modesty, embarrassment, and fear of misdiagnosis should be reduced in educational interventions through dialogue. Efforts to combat barriers in getting the Pap test must be undertaken to build the confidence of minority women through educational activities such as role-plays, psychodramas, or simulations. The construct of changes in the physical environment has not yet been used in the literature and our study lends support to the utilization of this dimension in future interventions. It is imperative that access and availability of Pap tests be increased for minority women at all locations in the U.S., especially for those without insurance and those who are indigent.

Our study found that in order to sustain the behavior of getting regular Pap tests, several correlates are essential. For sustenance of the behavior of getting regular Pap tests in both those who were not getting Pap tests and those who were getting Pap tests, all three constructs of MTM were significant and accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance. The construct of social support, which, in MTM, is more broadly referred to as changes in the social environment, has been used in the literature in the context of maintaining the behavior of getting Pap tests [39]. In many minority cultures, family and friends play an important role in the decision-making process for an individual. People are easily influenced by what others say or think of them. This aspect can be used as a potential advantage in health promotion interventions directed toward minority women for enhancing screening through Pap tests. Besides the traditional use of family, friends, and health professionals, in this regard, social media and advertisements are also gaining popularity and must be utilized more strategically in educational interventions. The constructs of emotional transformation and practice for change are unique to MTM and have not been tapped into in the past in the context of promoting the maintenance of Pap tests. Emotions or feelings are a powerful determinant of our behavior. If these can be harnessed into goals, then we can achieve our goals more effectively while combating self-doubt and fostering self-motivation. Educational interventions directed toward promoting Pap tests for minority women should facilitate participants to recognize their emotions, modulate these emotions, self-motivate themselves, and guide these emotions toward the goal of scheduling appointments with a physician and getting the Pap tests done on time. Likewise, a constant awareness of the importance of getting the Pap test done every three years can feed into building the practice for changing the construct of MTM.

While examining the socio-economic and healthcare access variables, as expected, less education, lack of health insurance, being unemployed, having less income, and not getting a recommendation from a healthcare provider were all significantly higher in the participants who did not receive the Pap test in the past three years. Influencing the socio-economic factors are under the purview of making structural policy changes but the lack of recommendation by healthcare providers is amendable through better education and training of healthcare providers that must be doggedly pursued.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was the first to utilize a contemporary, fourth-generation Multi-theory Model in explaining the correlates of cervical cancer screening among minority women. The instrument used in the study had very good psychometric properties. The sample used in the study was nationally representative. The study had an adequate power and sample size to discern medium effect sizes. The study also provided support to MTM, an upcoming theoretical framework. However, there were some limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional nature of the design precludes making temporal causal inferences between the independent and dependent variables. Future studies must utilize longitudinal experimental designs to provide more definitive evidence. Second, the study did not collect direct data in the form of medical records of Pap tests and relied only on self-reports, which are subject to biases. While some variables such as attitudes can only be measured through self-reports, future studies must utilize more objective data for variables that can have other means of measurement. Another limitation concerns the conducting of this survey only in English, which limited our sample to only those who could read and speak English. Future studies should offer other languages, e.g., Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, etc., to potentially capture more minority women. Finally, the study did not measure the stability of the instrument by test–retest reliability coefficients. Future studies, especially those undertaking interventional research, must test the stability of the instrument.

5. Conclusions

In the U.S., minority women have lower rates of cervical cancer screening through Pap tests. Efforts must be undertaken to increase these rates. The study identified contemporary theory-based correlates of cervical cancer screening among minority women using the framework of MTM and found that all constructs of this theory were significant predictors. The constructs of participatory dialogue, behavioral confidence, and changes in the physical environment explained a substantial proportion of the variance in starting the behavior of getting Pap tests, while the constructs of emotional transformation, practice for change, and changes in the social environment, along with lack of health insurance and annual household income of less than $25,000, significantly explained the likelihood to sustain the Pap test behavior of getting it every three years. Health promotion interventions based on MTM must be implemented to address the disparities of lower cervical cancer screenings among minority women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and K.B.; methodology, M.S. and K.B.; software, K.B.; validation, K.B. and M.S.; formal analysis, K.B.; investigation, K.B., M.S. and S.R.; resources, M.S.; data curation, K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J., K.B. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, all; visualization, K.B.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S. and K.B.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was funded by the School of Public Health, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, internal grant number PG03008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (protocol #1804208-1/09-08-2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

Authors of this paper would like to acknowledge Kiara Batra for her assistance in creating the visualizations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buskwofie, A.; David-West, G.; Clare, C.A. A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2020, 112, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Sabatino, S.A.; White, M.C. Rural-Urban and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Invasive Cervical Cancer Incidence in the United States, 2010–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce Campbell, C.M.; Menezes, L.J.; Paskett, E.D.; Giuliano, A.R. Prevention of Invasive Cervical Cancer in the United States: Past, Present, and Future. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontham, E.T.H.; Wolf, A.M.D.; Church, T.R.; Etzioni, R.; Flowers, C.R.; Herzig, A.; Guerra, C.E.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, Y.T.; Walter, L.C.; et al. Cervical Cancer Screening for Individuals at Average Risk: 2020 Guideline Update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. In Health United States; U.S. Government Printing Office: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akinlotan, M.; Bolin, J.N.; Helduser, J.; Ojinnaka, C.; Lichorad, A.; McClellan, D. Cervical Cancer Screening Barriers and Risk Factor Knowledge Among Uninsured Women. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.C.; Chou, C.F.; Johnson, P.J.; Ward, A. Persistent Disparities in Pap Test Use: Assessments and Predictions for Asian Women in the U.S., 1982–2010. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2010, 12, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ogunwale, A.N.; Sangi-Haghpeykar, H.; Montealegre, J.; Cui, Y.; Jibaja-Weiss, M.; Anderson, M.L. Non-Utilization of the Pap Test Among Women with Frequent Health System Contact. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2016, 18, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavis, A.L.; Gravitt, P.E.; Rositch, A.F. Hysterectomy-Corrected Cervical Cancer Mortality Rates Reveal a Larger Racial Disparity in the United States. Cancer 2017, 123, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarinci, I.C.; Garcia, F.A.R.; Kobetz, E.; Partridge, E.E.; Brandt, H.M.; Bell, M.C.; Dignan, M.; Ma, G.X.; Daye, J.L.; Castle, P.E. Cervical Cancer Prevention: New Tools and Old Barriers. Cancer 2010, 116, 2531–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, A.F.; Yamashita, T. Racial Disparities in Routine Health Checkup and Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines among Women in the United States of America. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi, C.; Sandhu, P.; Selix, N. Cervical Cancer Screening Among Minorities in the United States. J. Nurse Pract. 2016, 12, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, M.K.; Campbell, S.; Ursin, G.; Tropé, A.; Nygård, M. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening Faced by Immigrants: A Registry-Based Study of 1.4 Million Women in Norway. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoska, P.; Aksakal, T.; Yilmaz-Aslan, Y. Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening among Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany: Results from a Large-Scale Population Survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminisani, N.; Armstrong, B.K.; Canfell, K. Cervical Cancer Screening in Middle Eastern and Asian Migrants to Australia: A Record Linkage Study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012, 36, e394–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla, V.; Panagiotopoulou, E.K.; Deltsidou, A.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Kostagiolas, P.; Niakas, D.; Labiris, G. Level of Awareness Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Female Syrian Refugees in Greece. J. Cancer Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsiji, O.; Wilkes, L.; Peters, K.; Jackson, D. Knowledge, Attitudes and Usage of Cancer Screening among West African Migrant Women. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Hu, S.Y.; Zhao, F.H.; Smith, J.S.; Qiao, Y.L. Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake Between Chinese Migrant Women and Local Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cancer Control 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, C.M.; Morales-Campos, D.Y.; Carmona, C.M.; Ouyang, Y.; Liang, Y. Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Education and Navigation: Results of a Community Health Worker Intervention. Health Promot. Pract. 2016, 17, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, T.A. Cervical Cancer: Prevention and Early Detection. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 33, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramondetta, L.M.; Meyer, L.A.; Schmeler, K.M.; Daheri, M.E.; Gallegos, J.; Scheurer, M.; Montealegre, J.R.; Milbourne, A.; Anderson, M.L.; Sun, C.C. Avoidable Tragedies: Disparities in Healthcare Access among Medically Underserved Women Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsui, J.; Saraiya, M.; Thompson, T.; Dey, A.; Richardson, L. Cervical Cancer Screening among Foreign-Born Women by Birthplace and Duration in the United States. J. Women’s Health 2007, 16, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlow, L.A.V.; Waller, J.; Wardle, J. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening among Ethnic Minority Women: A Qualitative Study. J. Fam. Plan. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 41, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, B.; Alnaji, N.; Watanabe-Galloway, S.; Leypoldt, M. Cervical Cancer Attitudes and Knowledge in Somali Refugees in Nebraska. Pedagog. Health Promot. 2017, 3, 81S–87S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Nunes, M.; Antunes, M.D.L.; Heleno, B.; Dias, S. Factors Associated with Cervical Cancer Screening Participation among Migrant Women in Europe: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inturrisi, F.; Aitken, C.A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; van den Brule, A.J.C.; Molijn, A.; Hinrichs, J.W.J.; Niesters, H.G.M.; Siebers, A.G.; Schuurman, R.; Heideman, D.A.M.; et al. Clinical Performance of High-Risk HPV Testing on Self-Samples versus Clinician Samples in Routine Primary HPV Screening in the Netherlands: An Observational Study. Lancet Reg. Health—Eur. 2021, 11, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerly, E.; Bonde, J.; Schee, K.; Pedersen, H.; Lönnberg, S.; Nygård, M. Self-Sampling for Human Papillomavirus Testing among Non-Attenders Increases Attendance to the Norwegian Cervical Cancer Screening Programme. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acera, A.; Manresa, J.M.; Rodriguez, D.; Rodriguez, A.; Bonet, J.M.; Trapero-Bertran, M.; Hidalgo, P.; Sànchez, N.; de Sanjosé, S. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Coverage: A Randomised, Community-Based Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Flores, C.E.; Gomez Gutierrez, G.; Ortiz Leon, J.M.; Cruz Rodriguez, D.; Sørbye, S.W. Self-Collected versus Clinician-Collected Cervical Samples for the Detection of HPV Infections by 14-Type DNA and 7-Type MRNA Tests. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, T.L.; Wilson, K.M.; Smith, J.L.; Coronado, G.; Vernon, S.W.; Fernandez-Esquer, M.E.; Thompson, B.; Ortiz, M.; Lairson, D.; Fernandez, M.E. AMIGAS: A Multicity, Multicomponent Cervical Cancer Prevention Trial among Mexican American Women. Cancer 2013, 119, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, V.M.; Hislop, T.G.; Jackson, J.C.; Tu, S.P.; Yasui, Y.; Schwartz, S.M.; Teh, C.; Kuniyuki, A.; Acorda, E.; Marchand, A.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Interventions to Promote Cervical Cancer Screening among Chinese Women in North America. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuta-Jimenez, A.O.; Smith, G.P.A.; Brown, K.K. Patterns and Correlates of Cervical Cancer Prevention Among Black Immigrant and African American Women in the USA: The Role of Ethnicity and Culture. J. Cancer Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevik, T.B.; Laake, P.; Bjørkly, S. Effect of Culturally Tailored Education on Attendance at Mammography and the Papanicolaou Test. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 55, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandorf, L.; Bursac, Z.; Pulley, L.; Trevino, M.; Castillo, A.; Erwin, D.O. Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening among Latinas Attending Culturally Specific Educational Programs. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2008, 2, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Bastani, R.; Vida, P.; Warda, U.S. Results of a Randomized Trial to Increase Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening among Filipino American Women. Prev. Med. 2003, 37, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.J.; Halbert, C.H.; Bixby, R.; Pimentel, S.; Shea, J.A. Community Health Worker Intervention to Decrease Cervical Cancer Disparities in Hispanic Women. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Schuchard, H.; Burston, B.; Yamashita, T.; Albert, S. Interventions to Reduce Healthcare Disparities in Cancer Screening Among Minority Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavel, M.; Genderson, M.W. Daughter-Initiated Cancer Screening Appeals to Mothers. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.E.; Gonzales, A.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Williams, J.; Saavedra-Embesi, M.; Chan, W.; Vernon, S.W. Effectiveness of Cultivando La Salud: A Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Promotion Program for Low-Income Hispanic Women. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuño, T.; Martinez, M.E.; Harris, R.; García, F. A Promotora-Administered Group Education Intervention to Promote Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in a Rural Community along the U.S.-Mexico Border: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer Causes Control 2011, 22, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Jain, M.; Nahar, V.K.; Sharma, M. Predictors of Behaviour Change for Unhealthy Sleep Patterns among Indian Dental Students. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penny, K.; Sharma, M.; Flischel, A.E.; Brodell, R.T.; Nahar, V.K. Atopic Dermatitis: Preventing and Managing the Itch That Rashes, and a Case for the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) for Health Behavior Change for Educational Interventions. SKIN J. Cutan. Med. 2021, 5, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Dai, C.-L.; Batra, K.; Chen, C.-C.; Pharr, J.R.; Coughenour, C.; Awan, A.; Catalano, H. Using the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) of Health Behavior Change to Explain the Correlates of Mammography Screening among Asian American Women. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Asare, M.; Largo-Wight, E.; Merten, J.; Binder, M.; Lakhan, R.; Batra, K. Testing Multi-Theory Model (Mtm) in Explaining Sunscreen Use among Florida Residents: An Integrative Approach for Sun Protection. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Batra, K.; Batra, R. A Theory-Based Analysis of Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among African Americans in the United States: A Recent Evidence. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M.; Agyei-Baffour, P.; Lanning, B.A.; Owusu, A.B.; Commeh, M.E.; Boozer, K.; Koranteng, A.; Spies, L.A.; Montealegre, J.R.; Paskett, E.D. Multi-Theory Model and Predictors of Likelihood of Accepting the Series of HPV Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Study among Ghanaian Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Petosa, R.L. Measurement and Evaluation for Health Educators; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).