Word Order in Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Initial Findings

Abstract

1. Introduction

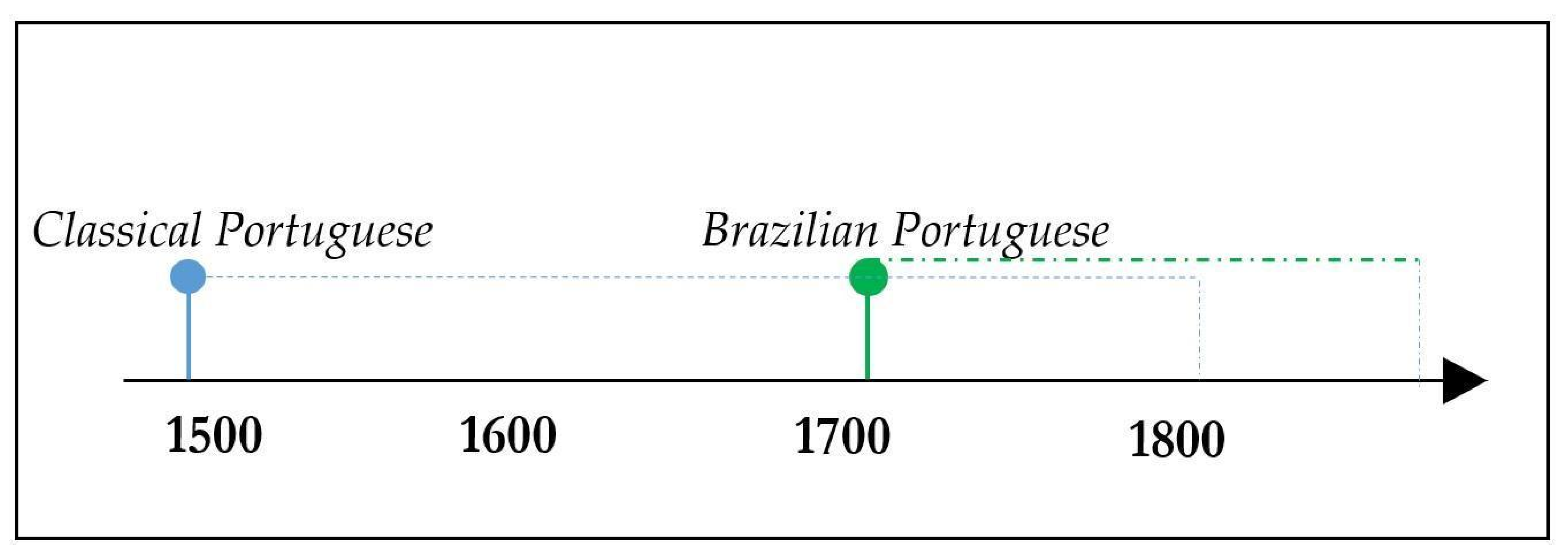

2. Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Characterization and Relevance

- Expanding the scope of investigation into the history of the Portuguese language in Brazil to include 17th-century texts;

- Carrying out comparative research between ClP and ColBP, without necessarily assimilating the latter to linguistic phenomena associated with BP.

3. Word Order Patterns in Classical Portuguese

| (1) | [ForceP | [TopP* (Topic) | || | [FocP (Focus) | [KontrP (Kontr) | [FinP | [TP ]]]]]] |

- OldP > ClP: Multiple AgrS specifiers (yes > no)

- ClP > EP: C attracts V (yes > no)

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

| (2) | a. | Ora | notem: | o | curso | do | Sol | material | ||||||

| now | notice | the | course | of.the | Sun | material | ||||||||

| […] | corre | em | cada | hora | ||||||||||

| runs | in | each | hour | |||||||||||

| trezentas | e | oitenta | mil | légoas | (ColBP) | |||||||||

| three.hundred | and | eighty | thousand | leagues | ||||||||||

| ‘Now notice: the course of the material Sun […] runs three hundred and eighty thousand leagues every hour.’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | O | Sol | […] | corre | a | cada | hora | |||||||

| the | Sun | runs | in | each | hour | |||||||||

| trezentas | e | oitenta | mil | légoas | ||||||||||

| three.hundred | and | eighty | thousand | leagues | (ClP) | |||||||||

| ‘The Sun […] runs three hundred and eighty thousand leagues every hour.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (3) | a. | que | muito | que | diga | eu, | que | ||||||||||

| how | much | that | say | I | that | ||||||||||||

| com | aquela | Capa | está | Cristo | cubrindo | ||||||||||||

| with | that | cloak | is | Christ | covering | ||||||||||||

| nossas | culpas. | (ColBP) | |||||||||||||||

| our | faults | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘why should it be a wonder that I say Christ is covering our faults with that cloak?’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | que | muito | é | que | digam | e | informem | ||||||||||

| how | much | is | that | say | and | inform.3pl | |||||||||||

| […] | que | lhes | sobejam | merecimentos | |||||||||||||

| that | to.them | remain | merits | (ClP) | |||||||||||||

| ‘why should it be any wonder that they say and testify […] that their merits reach to the rooftops?’ | |||||||||||||||||

4.2. Methods

- clause type: main clause, complement clause, or adjunct clause;

- syntagmatic type of the fronted constituent: nominal phrase; prepositional phrase; adverbial phrase;

- syntactic function of the fronted constituent: subject, accusative complement, dative complement, oblique complement, adjunct, nominal predicate, dislocated topic, or parenthetical;

- discursive or informational function: discourse marker, vocative, complementizer, focalizing particle, V2 topic, contrastive topic, frame-setting topic, contrastive focus, or informational focus.16

5. Results

5.1. General Word Order Patterns

| (4) | a. | Temos | o | exemplo | entre | mãos | ||||||||||

| have.1pl | the | example | between | hands | (V1; null S) | |||||||||||

| ‘We have the example between (our) hands’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Quiseram | os | antigos | pintar | a | justiça | ||||||||||

| wanted | the | ancient.ones | paint | the | justice | |||||||||||

| mais | rigurosa | (V1; VS) | ||||||||||||||

| more | strict | |||||||||||||||

| ‘The ancient ones wanted to represent Justice as (being) more strict’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (5) | a. | [NP-S | as | outras | prophecias] | cumprem-se | ||||||||||||||||||

| the | other | prophecies | fulfill.3pl=inh | |||||||||||||||||||||

| a | seu | tempo | (ClP, SV) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| in | their | time | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The other prophecies fulfill themselves in their (due) time’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | [PP | Na | parábola | das | dez | Virgens], | fallava | |||||||||||||||||

| in.the | parable | of.the | ten | virgins | spoke.imperf | |||||||||||||||||||

| [NP-S | Christo | Senhor | nosso], | propria | e | |||||||||||||||||||

| Christ | Lord | our | proper | and | ||||||||||||||||||||

| literalmente | do | dia | do | Juiso | (ClP, VS) | |||||||||||||||||||

| literally | of.the | day | of.the | Judgment | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘In the Parable of the Ten Virgins, Christ our Lord spoke, properly and literally, about the day of Judgment’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (6) | a. | porque | lhe | acomodam | bem | as | penas | (ColBP; V1) | ||||||||||||||||||

| because | 3sg.dat | accommodate | well | the | feathers | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘because the feathers accommodate well to it [love].’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | porque | [com | elas] | nos | explica | |||||||||||||||||||||

| because | with | them | us | explains | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| o | quanto | por | nós | padeceu. | (ColBP; V2) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| the | much | for | us | suffered | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘because with them [the wounds] he explains to us how much he suffered for us.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | porque | [como | o | cair | é | pensão] | […] [em | |||||||||||||||||||

| because | as | the | falling | is | burden | in | ||||||||||||||||||||

| nossa | própria | fraqueza] | temos | algũa | desculpa | (ColBP; V3) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| our | own | weakness | have.1pl | some | excuse | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘because, as falling is a burden, we have some excuse for our own weakness.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (7) | a. | porque | [aos | pequenos] | concede-se-ha | misericordia | (ClP; V2) | ||||||

| because | to.the | little.ones | grant=pass=fut | mercy | |||||||||

| ‘because mercy will be given to the little ones.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | porque | [conforme | cada | um | tem | o | coração], | ||||||

| because | according.to | each | one | has | the | heart | |||||||

| [assim] | prophetisa. | (ClP; V3) | |||||||||||

| so | prophesies | ||||||||||||

| ‘because according to (where) each one has their heart, so they prophesy.’ | |||||||||||||

5.2. Preverbal Constituents with Postverbal Subjects in Main Clauses

- does not show any cases of dislocation, unlike in ClP;

- significantly shows more cases of contrastive focus;

- shows fewer sentences with an aboutness topic or a contrastive topic.

| (8) | a. | Primeiramente | [com | aquelas | feridas] | representa | |||||||||

| firstly | with | those | wounds | represents | |||||||||||

| Cristo | o | quanto | nos | ama | (contr. focus) | ||||||||||

| Christ | the | much | us | loves | |||||||||||

| ‘Firstly, with those wounds, Christ represents how much he loves us’ (interpretation: ‘…it is with those wounds that Christ represents how much he loves us’) | |||||||||||||||

| b. | [A | Thomé] | mostrou | Cristo | cinco | Chagas; | |||||||||

| since | Thomas | showed | Christ | five | sores | ||||||||||

| porém | a | nós | cinco | mil | (contr. topic) | ||||||||||

| but | to | us | five | thousand | |||||||||||

| ‘To Thomas, Christ showed five sores; but to us, five thousand’ | |||||||||||||||

6. Discussions

| (9) | Pois | estai | certos, | fiéis, | [que] | se | não | ||||||||||||||||||||

| thus | be.2pl | certain | believers | that | if | neg | |||||||||||||||||||||

| correspondermos | de | outra | sorte | a | tão | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| correspond.fut.1pl | of | another | luck | to | such | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| grande | amor, | [que] | este | mesmo | amor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| great | love | that | this | same | love | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| se | há | de | converter | em | indignação | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| pass | will | part | turn.into | in | indignation | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Thus be certain, believers, that if we do not respond in another way to such great love, this same love will turn into indignation’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (10) | tantos | incêndios | sentia | no | coração, | |||||||||||||||

| so.many | fires | felt | in.the | heart | ||||||||||||||||

| que | parece | ∅ | encerrava | no | peito | |||||||||||||||

| that | seems | (that) | held | in.the | chest | |||||||||||||||

| novo | Etna, | novo | Mongibello… | |||||||||||||||||

| new | Etna | new | Mongibello | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘He felt so many fires in his heart, that it seems like he held a new Etna, or a new Mongibello in his chest…’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

- in the order between subject and verb, because BP shows a subject-verb grammar;

- in the order between clitic and verb, because BP shows a proclitic grammar.

7. Conclusions

- unlike in ClP, in which V2 is the preferred option, the ColBP text shows a greater number of V1 order (if compared to V2 and V3) in all clause types;

- unlike in ClP, there is a smaller use of structures with an external topic, especially those embodied in left-dislocation and contrastive-topic constructions.

- a higher frequency of subject-verb clauses;

- a higher frequency of proclisis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Regarding this issue, an anonymous reviewer has also mentioned that the acceptability of X*VS patterns is still a major point of variation among the Romance languages today. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | This text shall be integrated into the Electronic Corpus of Historical Documents of the Hinterland (CE-DOHS; Carneiro and Lacerda 2024). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | This text is available with syntactic annotation in the Tycho Brahe Parsed Corpus of Historical Portuguese (TBC; Galves et al. 2017). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Lucchesi (2019) mentions these continuous and frequent interactions as reasons that led to the non-emergence of a Portuguese-based creole in Brazil. The debate about whether Brazilian Portuguese was a creole language was frequent at the end of the 20th century. However, nowadays no one assumes that this has been a characteristic of Brazilian Portuguese in any of its developmental stages (Tarallo 1993). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | It is beyond the scope of this work to address the creation of Brazilian Portuguese varieties, which are divided, according to Lucchesi (1994), into a cultured variety, spoken by Brazilians with a higher level of education and greater socioeconomic condition, generally born in State capitals, and the popular variety, spoken by Brazilians with a lower level of education, having a lower socioeconomic status, generally born in the country’s hinterland. We recognize, however, that such varieties show considerable linguistic divergences, probably associated with the process of formation and the acquisition of Portuguese by European descendants on one hand and Africans and indigenous peoples and their descendants on the other hand, during the colonial period (cf. Mattos e Silva 2004 and Lucchesi 2015 for a more in-depth discussion regarding the origins of Brazilian Portuguese along these two sociolinguistic trends). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | We consider that, although more fundamental grammatical properties of a linguistic system could hypothetically take place, the sociolinguistic context represented by ColBP, together with the lack of time to implement some changes, would not promote the advent of meso- or macroparameters. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | This variety is commonly referred to as português brasileiro culto falado (‘cultured’ spoken Brazilian Portuguese). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Clitic placement in pre- or postverbal position (enclisis or proclisis) was guided by several syntactic contexts in ClP, some requiring proclisis, others requiring enclisis, and yet others allowing for variation between proclisis and enclisis. Among these, Galves et al. (2005) suggest the existence of a Variation Context 2, which includes sentences containing a verb in initial position in a second-coordinate clause or preceded by one or more dependent clauses (examples from André de Barros’ The Life of the Apostolic Father António Vieira, 17th century, quoted in Galves et al. 2005, p. 49):

This context showed a tendency for enclisis combined with a more pronounced variation between the studied authors. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Examples of archives containing documents related to the colonization of Brazil are the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (AHU) and the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (IAN-TT), both located in Portugal. The task of retrieving these texts may be costly and laborious because the collections are organized according to a specific classification that does not always meet the relevant criteria for linguistic research. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The sermons written by Father António Vieira have already been the subject of linguistic studies which, when compared with the letters written by the same author, pointed out the strong presence of stylistic marks interfering in the behavior of certain linguistic phenomena, such as the order of clitic pronouns in the sentence, cf. Galves (2002). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Available online: https://digital.bbm.usp.br/handle/bbm/1. accessed on 3 January 2024. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | The lack of any relevant morphosyntactic changes in the new edition provides support for the choice of this material for linguistic research. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | The CE-DOHS platform brings together a significant set of texts written in Brazil between the 16th and 20th centuries, the vast majority of which were produced by Brazilians of different ethnicities (Portuguese, Indigenous, and African descendants), in addition to containing oral data produced in the late 20th century. These documents have significant socio-historical control related to the authorship and social context of writing the manuscripts, in addition to providing an interface that allows an exploration of the material based on philological and/or grammatical goals. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | G-tests were used if a table displayed at least one cell with less than 5 occurrences, and this option is indicated in the respective captions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | From an analysis of chi-square residuals, the difference between ColBP and ClP resides in the V2 factor (with 40% and 53%, respectively). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | From an analysis of chi-square residuals, the difference between ColBP and ClP resides in the V > 2 factor (with 3% and 37%, respectively). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | The TBC platform is composed of texts written in Portuguese between 1380 and 1978, with more than one million words of parsed text. Most of its texts are representative of ClP and modern European Portuguese, although some representative texts of Old Portuguese and modern Brazilian Portuguese have been recently included as well. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | From an analysis of chi-square residuals, the difference between ColBP and ClP resides in the ‘DP accusative complement’ factor (with 10% and 3%, respectively). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | There were no clear cases of Informational Focus at the left periphery, so this category was ignored in the table. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | From an analysis of chi-square residuals, the difference between ColBP and ClP resides in the ‘contrastive focus’ factor (with 29% and 8.5%, respectively). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | The two first discursive/informational functions (discourse marker and vocative) are placed at the external clausal domain; the last one (informational focus) is believed not to exist at the left periphery of Portuguese in any stage but was included there for the sake of completeness. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | The total is not equivalent to the total of XVS sentences in Table 3 because there are other requirements regarding the category, removing other possible combinations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | As already mentioned, the notions of internal and external left-peripheral positions are indirectly motivated by the difference between enclisis and proclisis and directly motivated by their position in the syntactic marker, higher than FocP (cf. Benincà 1995). Interestingly, frame-setters are also external to the clause, but their percentages are similar in the two grammars. According to Benincà and Poletto (2004), they occupy the Spec, FrameP position at the very top of the left periphery; however, the results in Galves et al. (2005) suggest, that in ClP, frame-setters may occupy either a clause-external or clause-internal position, possibly Spec, KontrP in Galves and Kroch’s (2016) terms, depending on its length in terms of phonological words. Cf. Prévost (2003) for an explanation for why some locative phrases may be considered as focus-like. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Alkimim, Ilma. 2014. Sermões de Eusébio de Matos: Edição Crítica e Estudo. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, Aroldo. 2015. On the Emergence of Topicalization in Modern European Portuguese: A Study at the Syntax-Information Structure Interface. Estudos Linguísticos 11: 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, Aroldo. 2020. A gramática do português colonial brasileiro: Uma agenda de pesquisas. [Apresentação no painel “Sociolinguística Histórica, tratamento de corpora e história do português brasileiro”] Abralin ao Vivo: Linguists Online, December 7. Available online: https://aovivo.abralin.org/lives/sociolinguistica-historica/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Andrade, Aroldo, and Charlotte Galves. 2019. Contrast and word order: A case study on the history of Portuguese. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, Afrânio. 1999. Para uma História do Português Colonial: Aspectos Linguísticos em Cartas de Comércio. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Benincà, Paola. 1995. Complement clitics in medieval Portuguese: The Tobler-Mussafia Law. In Language Change and Verbal Systems. Edited by Adrian Battye and Ian Roberts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 325–44. [Google Scholar]

- Benincà, Paola, and Cecilia Poletto. 2004. Topic, Focus and V2: Defining the CP sublayers. In The Structure of CP and IP: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 2, pp. 52–76. [Google Scholar]

- Berlinck, Rosane. 1988. A Ordem V SN No Português do Brasil: Sincronia e Diacronia. Master’s thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Lara. 2020. A Gramática dos Pronomes Clíticos no Brasil Colônia: O Português Clássico na História do Português Brasileiro. Master’s thesis, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Lara, Aroldo Andrade, and Zenaide Carneiro. 2023. O português colonial brasileiro: Uma nova agenda de pesquisas entre o português clássico e o português brasileiro moderno. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Linguística Teórica e Aplicada 39: 202339253749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Zenaide, and Charlotte Galves. 2010. Variação e Gramática: Colocação de clíticos na história do português brasileiro. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem 18: 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Zenaide. 2005. Cartas Brasileiras (1809–1904): Um Estudo Linguístico-Filológico. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, Zenaide, and Mariana Lacerda. 2024. CE-DOHS: Corpus Eletrônico de Documentos Históricos do Sertão. Available online: https://www.uefs.br/cedohs/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Corôa, Williane. 2022. Rastreando as Origens do Português Brasileiro: A Dinâmica da Mudança na Escrita de “Homens Bons” na Bahia Colonial. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte, and Anthony Kroch. 2016. Main syntactic changes from a Principles-and-Parameters view. In The Handbook of Portuguese Linguistics. Edited by Leo Wetzels, Sérgio Menuzzi and João Costa. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte, Aroldo Andrade, and Pablo Faria. 2017. Tycho Brahe Parsed Corpus of Historical Portuguese. Available online: https://www.tycho.iel.unicamp.br/corpus/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Galves, Charlotte, Aroldo Andrade, Cristiane Namiuti, and Maria Clara Paixão de Sousa. Forthcoming. Classical Portuguese: Grammar and History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Galves, Charlotte. 2002. Syntax and Style: Clitic-placement in Padre Antonio Vieira. Santa Barbara Portuguese Studies 6: 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte. 2007. A língua das caravelas: Periodização do português europeu e origem do português brasileiro. In Descrição, História e Aquisição do Português Brasileiro. Edited by Ataliba Castilho, Maria Aparecida Torres Moraes, Ruth E. Vasconcellos Lopes and Sonia Maria Lazzarini Cyrino. Campinas and São Paulo: Pontes and Fapesp, pp. 513–28. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte. 2020. Relaxed V-Second in Classical Portuguese. In Rethinking Verb Second. Edited by Rebecca Woods and Sam Wolfe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 368–95. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte, Helena Britto, and Maria Clara Paixão de Souza. 2005. The change in clitic-placement from Classical to Modern European Portuguese: Results from the Tycho Brahe Corpus. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 4: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götze, Michael, Thomas Weskott, Cornelia Endriss, Ines Fiedler, Stefan Hinterwimmer, Svetlana Petrova, Anne Schwarz, Stavros Skopeteas, and Ruben Stoel. 2007. Information Structure. In Information Structure in Cross-Linguistic Corpora: Annotation Guidelines for Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, Semantics and Information Structure. Edited by Stefanie Dipper, Michael Götze and Stavros Skopeteas. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam, pp. 147–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hinterhölzl, Roland. 2004. Language Change versus Grammar Change: What diachronic data reveal about the distinction between core grammar and periphery. In Diachronic Clues for Synchronic Grammar. Edited by Eric Fuß and Carola Trips. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 131–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatek, Johannes. 2008. Sintaxis Histórica del Español y Cambio Lingüístico: Nuevas Perspectivas Desde las Tradiciones Discursivas. Madrid: Vervuert Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 2008. Some Notes on Comparative Syntax, with Special Reference to English and French. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard Kayne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, David. 1999. The Development of Language: Acquisition, Change, and Evolution. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lose, Alícia. 2022. Ver más allá del texto: Análisis material de los Pasquines Sediciosos de la Revolución de los Sastres en Bahía en el siglo XVIII. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie IV. Historia Moderna 35: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, Dante. 1994. Variação e norma: Elementos para uma caracterização sociolinguística do português do Brasil. Revista Internacional de Língua Portuguesa 12: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, Dante. 2015. Língua e Sociedade Partidas: A Polarização Sociolinguística do Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, Dante. 2019. Por que a crioulização aconteceu no Caribe e não no Brasil? Condicionamentos sócio-históricos. Gragoatá 24: 227–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, Diogo Barbosa. 1741. Bibliotheca Lusitana. Lisboa Occidental: Officina de Antonio Isidoro da Fonseca, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Ana Maria. 2019. Against V2 as a general property of Old Romance languages. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 15: Selected papers from Going Romance 30, Frankfurt. Edited by Ingo Feldhausen, Martin Elsig, Imme Kuchenbrandt and Mareike Neuhaus. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Marco Antônio. 2009. Competição de Gramáticas do Português na Escrita Catarinense dos Séculos 19 e 20. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mattos e Silva, Rosa Virgínia. 2004. Ensaios para uma Sócio-História do Português Brasileiro. São Paulo: Parábola. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoso, Katia. 2003. Ser Escravo no Brasil, 3rd ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Meisezahl, Marc. 2024. Learning to Lose: The Role of Input Variability in the Loss of V2. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pagotto, Emílio. 1992. A Posição dos Clíticos em Português: Um Estudo Diacrônico. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Sophie. 2003. Les compléments spatiaux: Du topique au focus en passant par les cadres. Travaux de linguistique 47: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Jânia M., and Marilza de Oliveira. 2021. Introdução. In História do Português Brasileiro, vol. 10: Dialetação e Povoamento. Da História Linguística à História Social. Edited by Jânia M. Ramos and Marilza de Oliveira. São Paulo: Contexto, pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Beth, Antony Kroch, and Beatrice Santorini. 2004. CorpusSearch 2 Users’ Guide. Available online: https://www.ling.edu/~beatrice/corpus-ling/CS-users-guide (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of Grammar: Handbook of Generative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Ian. 2019. Parameter Hierarchies and Universal Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tarallo, Fernando. 1993. Diagnosticando uma gramática brasileira: O português d’aquém-mar e d’além-mar ao final do século XIX. In Português Brasileiro: Uma Viagem Diacrônica. Edited by Ian Roberts and Mary Kato. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, pp. 69–105. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, António. 1907. Sermões, Pe. António Vieira. Edited by Gonçalo Alves. Porto: Chardron/Lello & Irmão Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Sam. 2015. Microvariation in Medieval Romance Syntax: A Comparative Study. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Percent | Occurrences: VS/Total |

|---|---|---|

| 18th century (1750) | 42% | 203/486 |

| 19th century (1850) | 31% | 144/469 |

| 20th century (1987) | 21% | 63/1262 |

| Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | Classical Portuguese | |

|---|---|---|

| Author | Eusébio de Matos (Brazil, 1629–1692) | António Vieira (Portugal, 1608–1697) |

| Textual Genre | Sermon (Ecce Homo) | Sermon (Sermões) |

| Edition | Conservative edition by I. Alkimim | Conservative edition by G. Alves |

| Number of words | 25,090 words | 53,855 words |

| Source | CE-DOHS | TBC |

| Variety | Verb Position/ Subject Expression | Verb-Subject | Subject-Verb | Null Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | V1 | 71 (49%) | 0 (0%) | 127 (53%) |

| V2 | 58 (40%) | 68 (61%) | 92 (38%) | |

| V > 2 | 17 (11%) | 43 (39%) | 21 (9%) | |

| Total | 146 (100%) | 111 (100%) | 240 (100%) | |

| Classical Portuguese | V1 | 97 (42%) | 0 (0%) | 74 (49%) |

| V2 | 122 (53%) | 86 (61%) | 64 (43%) | |

| V > 2 | 12 (5%) | 56 (39%) | 12 (8%) | |

| Total | 231 (100%) | 142 (100%) | 150 (100%) | |

| p-value | 0.0015 * | 0.9965 † | 0.6960 † |

| Variety | Verb Position/ Subject Expression | Verb-Subject | Subject-Verb | Null Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | V1 | 14 (63%) | 0 (0%) | 42 (65%) |

| V2 | 7 (32%) | 20 (74%) | 19 (29%) | |

| V > 2 | 1 (5%) | 7 (26%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Total | 22 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 65 (100%) | |

| Classical Portuguese | V1 | 6 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (80%) |

| V2 | 10 (62%) | 9 (75%) | 5 (12%) | |

| V > 2 | 0 (0%) | 3 (25%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Total | 16 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 39 (100%) | |

| p-value | 0.2238 † | 0.9931 † | 0.1532 † |

| Variety | Verb Position/ Subject Expression | Verb-Subject | Subject-Verb | Null Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | V1 | 20 (49%) | 0 (0%) | 91 (58%) |

| V2 | 17 (41%) | 56 (79%) | 62 (39%) | |

| V > 2 | 4 (10%) | 15 (21%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Total | 41 (100%) | 71 (100%) | 158 (100%) | |

| Classical Portuguese | V1 | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (42%) |

| V2 | 11 (55%) | 1 (20%) | 4 (21%) | |

| V > 2 | 1 (5%) | 4 (80%) | 7 (37%) | |

| Total | 20 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 19 (100%) | |

| p-value | 0.5839 † | 0.5982 † | 0.0002 † |

| Word Order Combinations | Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | Classical Portuguese |

|---|---|---|

| OV | 8 (21%) | 24 (15%) |

| AV | 22 (60%) | 118 (74%) |

| AAV | 5 (14%) | 18 (11%) |

| AOV | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 37 (100%) | 160 (100%) |

| p-value = 0.4904 | (G-test for independent samples) | |

| Type of Preverbal Constituent | Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | Classical Portuguese |

|---|---|---|

| DP accusative complement | 10 (10%) | 5 (3.6%) |

| DP dislocated topic | 0 (0%) | 13 (9.3%) |

| DP subject | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| PP dative complement | 2 (2%) | 5 (3.6%) |

| PP adjunct | 36 (39%) | 64 (45.7%) |

| AdvP or Adverbial Clause | 43 (46%) | 50 (35.7%) |

| Vocative | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Parenthetical | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Nominal predicate | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 94 (100%) | 140 (100%) |

| p-value = 0.0069 | (G-test for independent samples) | |

| Informationally Marked Construction | Colonial Brazilian Portuguese | Classical Portuguese |

|---|---|---|

| Clitic Left Dislocation | 0 (0%) | 6 (5%) |

| Hanging-Topic Left Dislocation | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Contrastive Focus | 23 (29%) | 11 (8.5%) |

| Aboutness Topic (V2 Topicalization) | 7 (9%) | 20 (16%) |

| Frame-Setting Topic | 47 (59%) | 74 (58%) |

| Contrastive Topic | 2 (3%) | 15 (12%) |

| Total | 79 (100%) | 127 (100%) |

| p-value = 0.0124 | (G-test for independent samples) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Andrade, A.L.; Cardoso, L.d.S. Word Order in Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Initial Findings. Languages 2024, 9, 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9080269

de Andrade AL, Cardoso LdS. Word Order in Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Initial Findings. Languages. 2024; 9(8):269. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9080269

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Andrade, Aroldo Leal, and Lara da Silva Cardoso. 2024. "Word Order in Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Initial Findings" Languages 9, no. 8: 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9080269

APA Stylede Andrade, A. L., & Cardoso, L. d. S. (2024). Word Order in Colonial Brazilian Portuguese: Initial Findings. Languages, 9(8), 269. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9080269