Abstract

Multilingualism has become the norm in families all over the world. These families need to juggle their children’s linguistic identity and integration in their contexts. They may also need professional advice about which language(s) they should use at home, especially when children present with developmental disorders. There is a dearth of studies addressing the role parental views play in home-language maintenance with children with developmental disorders. This study is conducted in Spain, where Spanish is the national language, along with local languages in certain regions, as well as foreign languages. This qualitative study aimed to deepen our understanding of the views about language choice of multilingual families whose children have either typical language development or a developmental disorder in Spain. We recruited 26 parents of multilingual children aged between 5 and 10 years, from different linguistic backgrounds. Semi-structured online interviews were conducted. The data were analyzed through reflexive thematic analysis. The findings illustrate the complexity and nuance of parents’ views and decisions regarding language choice in their contexts. The themes included identity and belonging, as well as the influences of external advice on parental decisions. It is important that professionals such as speech–language therapists understand these views to enable them to deliver family-centered care.

1. Introduction

The current state of multilingualism around the globe is that there are more individuals who speak two or more languages than there are monolinguals. More than 7000 languages are spoken in the world, so it is natural to find countries with more than one official language. Some countries recognize nearly 40 languages (e.g., Bolivia); however, only a handful of them would be considered lingua francas (Singh et al. 2012). In recent years, there has been a growth in migration, which has led to cultural intermixing, contributing to the multilingual world we now live in (Paradowski and Bator 2018). In Spain, specifically, the National Institute of Statistics (INE 2023) reports that 11.4% of its population originates from a different country, making it the country in the European Union with the second highest migration rate. As a result, more children are now born into multicultural and multilingual households, and people learn additional languages out of necessity, as well as for pleasure.

In this context, defining multilingualism can be somewhat complex. Researchers share multiple definitions, depending on the number of languages known, the age and manner of acquisition, proficiency, functional or contextual use of languages, linguistic identity, language switching, etc. (Grech and McLeod 2012; Marian and Hayakawa 2021; Surrain and Luk 2019). Grech and McLeod (2012) explain that each definition of multilingualism can be organized from the most to the least conservative. In the current study, we opt for a less conservative approach, where we understand multilingualism as a continuum that would include any person who can be functional in two or more languages, with different levels of objective or subjective proficiency.

1.1. Linguistic Context in Spain

To facilitate a better understanding of the setting where this research is carried out, we provide a summary of its linguistic context. Spain is a multilingual country where there are several official and non-official local languages, as well as speakers of foreign languages. In this context, Spanish (referring to the Iberian variant of the language) is the national language, along with a few recognized languages that are co-official in their respective regions or autonomous communities: Galician (galego), which is official in the community of Galicia; Basque (euskara), spoken in the Basque Country and Navarra; and Catalan (català), official in the community of Catalonia, along with its variations in the Valencian Community (Valencian language) and the Balearic Islands (Balearic Catalan). The multicultural nature of the country adds another layer to decisions parents make about the potential use of languages in multilingual family settings.

The language policies concerning the use and status of the regional languages in Spain have changed over the last century. At present, even though some of the regional languages are co-official and their instruction is obligatory in schools in their respective regions, the social perception and the value assigned to these languages are often subjects of debate. This situation leaves the regional languages in a state of vulnerability, calling for measures to prevent their disappearance (Ramallo 2022). One of the challenges faced by institutions when developing language policies is the lack of intergenerational use of the languages. Nevertheless, there is now a generation of neohablantes or new speakers (Ramallo 2012; Soler and Zabrodskaja 2017), who learned Spanish as their first language but also make active efforts to learn and use the regional languages and cultural traditions to pass them on to the following generations (Nandi 2019). The use of regional languages represents a symbol for transmitting the identity of the community (Lasagabaster 2007).

Considering that languages can be linked to politics, the authors aim to provide the reader with a general overview of the situation without taking sides, except to declare that all languages serve a purpose and are “equally important from a linguistic and anthropological point of view” (Moreno-Fernández 2015, p. 2). Therefore, in this study we explore parental choices in relation to which language(s) they chose when raising their children, as these choices may be influenced by the experiences and attitudes of families, depending on the sociolinguistic context where they live.

1.2. Language Maintenance and Identity

In a context where there is a growth in intercultural families, the concept of language maintenance arises in relation to the decisions parents make in relation to language use and transmission to the following generations (Schalley and Eisenchlas 2020). Those decisions can be influenced by different factors, such as the family’s attachment to their cultural identity (Gharibi and Seals 2020) and/or the perceived usefulness and value of their language(s) (Curdt-Christiansen and Wang 2018), as well as external factors (e.g., language regulations, institutional support, societal ideologies) (Mirvahedi 2021). On this basis, the family’s background, current environment, and their future plans and expectations would play a role in shaping their views and priorities regarding language choice (Akgül et al. 2019; Fuentes 2020; Seo 2021).

The relationship between language and identity is somewhat complex. In the current study, identity is encompassed within Bucholtz and Hall’s (2005) interpretation, where a person constructs and modifies their identities in interaction with others to distance themselves from or associate with a group. In some cases, parents may pass on their languages to their children to create familial bonds (Jung 2022) and transmit a sense of belonging (Berardi-Wiltshire 2017), thereby building a shared linguistic identity that would create a bridge, connecting their present to their roots. For example, Lee (2013) found that Korean American parents may choose to expose their children to their heritage language to transmit a “positive ethnic identity”. However, Mirvahedi and Jafari (2021) found that the historical stigmatization of the Azerbaijani language and culture in Iran might lead parents to feel conflicted about their ethnic language and identity, and they may choose to expose their children to Farsi over Azerbaijani.

Some researchers have reported that parents may worry about losing their linguistic and cultural identity to the majority language and culture (Kwon 2017; Wang and Gao 2021), and as a result, they make efforts to transmit their heritage to their children through passing on their home language. However, even though children can learn the customs and language from their parents, they might also develop a bicultural identity by undergoing a “selective acculturation” that allows them to adapt to the environment while preserving elements of the culture of origin (Rodríguez-García et al. 2021).

1.3. Parental Concerns and Professional Advice

With globalization and the increase of multilingual populations, there has been a proliferation of multilingual children who present with developmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, developmental language disorder), who require services such as speech and language therapy. Some researchers have found that parents may be concerned about the language development of multilingual children (Kostoulas and Motsiou 2022), and whether a multilingual education could be stressful for their child when they present developmental disorders (Howard et al. 2021). However, there is evidence that multilingualism does not cause developmental disorders (Moore and Pérez-Méndez 2006; Peña et al. 2023). Multilingualism may be linked with cognitive and social benefits in children with communication difficulties (Peristeri et al. 2021).

To date, there have been few studies exploring the decisions parents make in relation to which language(s) to use when raising multilingual children with developmental disorders. Those studies usually include small sample sizes [n ≤ 35] or are case studies, including mainly families of children with autism spectrum disorder (Hampton et al. 2017; Howard et al. 2021; Ijalba 2016; Sher et al. 2022), families of children with language delays (Mirvahedi and Hosseini 2023) and children ‘labeled as disabled’ (Cioè-Peña 2021, p. 1). These studies show that parents often share similar views, priorities and concerns as families of typically developing children in terms of transmitting their home language and identity. However, there is an additional concern of multilingualism amplifying the limitations inherent to the disorder (Hampton et al. 2017), which may influence parents’ choices about language transmission (Cioè-Peña 2021).

One of the current paradigms in healthcare and education is family-centered practice, where the professional (e.g., speech–language therapist, teacher, etc.) would include the family members as active agents in education and healthcare practice. This includes consideration of their background and current environment, as well as their personal needs, desires and concerns (Klatte et al. 2023). Therefore, it is important to understand parental views and concerns about the language(s) that they choose when raising their children (typically developing and those with developmental disorders), so that practitioners can tailor their approach to the needs of the families.

There is evidence to suggest that adjusting professional practices to the cultural and linguistic needs of multilingual families is one of the challenges faced by practitioners (Peña 2016). In a survey study conducted by Nieva et al. (2020), professionals reported feeling overwhelmed by the lack of available resources to provide tailored services to multilingual families. These professionals reported that they had limited knowledge about the acquisition and development of more than one language. Further evidence indicates that multilingual families may be encouraged to drop one or more languages, which might differ from the parents’ preferences (Bezcioglu-Göktolga and Yagmur 2018; Mirvahedi and Hosseini 2023). In addition, researchers suggest that restricting the home language might have lasting effects on family dynamics, the child’s identity construction and their social–emotional development and well-being (Cox et al. 2021; Kohnert et al. 2021). Researchers have found that these recommendations have been provided to parents of both typically developing children (Bezcioglu-Göktolga and Yagmur 2018) and those with a developmental disorder (Hampton et al. 2017). Practitioners may make these recommendations based on the assumption that learning more than one language might be confusing for the child and hinder their language development. However, these recommendations might be rooted in a monolingual ideology that bolsters the further “marginalization” of multilinguals (Peña et al. 2023, p. 2).

Professionals hold implicit or explicit attitudes towards multilingualism that can influence their practices and recommendations (Ijalba 2016), which in turn might impact parents’ choice of language(s) in the home setting (Bezcioglu-Göktolga and Yagmur 2018; Cioè-Peña 2021). Therefore, it is important that practitioners such as speech–language therapists, teachers or doctors recognize that they hold positions of power, and with this power comes responsibility. Therefore, given that more than half of the world’s population is multilingual (Akgül et al. 2019), providing professional advice from a monolingual lens could potentially be more harmful than helpful for the child, considering that family ties and identities can be constructed through a shared language (Tseng 2020).

1.4. Aims and Objectives

The overall aim of this study was to examine parental views about language choice and home language maintenance when raising their children who were typically developing or presenting with developmental disorders. There were two objectives: to explore the views of parents about their preferences and priorities in relation to language choice and to explore the views of parents about what external factors influenced their decisions about language choice when raising their children. This study sought to answer the following research questions:

- What influences language choice in multilingual families?

- What priorities in relation to choices about language do parents have with regards to their children’s language acquisition?

- How do parents juggle languages in the contexts where they live?

- How are parents’ views influenced by external advice?

2. Materials and Methods

Given that the aims and objectives of this study are oriented towards exploring what, why and where questions (Sandelowski 2000), we opted for a qualitative approach because it would enable us to explore the phenomena in depth and capture the heterogeneity in the participants’ data. The research follows an experiential framework, with a relativist approach (Braun and Clarke 2022), where the aim is to explore the participants’ views and perspectives about a topic.

To ensure integrity (Holmlund et al. 2020), this study was approved by the ethics committee from the Faculty of Psychology of the Complutense University of Madrid. The participants were informed about the research and their rights regarding the participation and were requested to provide consent. After they agreed to participate, they were requested to complete a survey that included demographic information about themselves and their children, as well as the languages spoken by all the family members. All the data were stored securely to protect their privacy and were pseudonymized in accordance with the Spanish Data Protection Act 3/2018. To enhance rigor in this study, we used the COREQ checklist (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) (Tong et al. 2007).

2.1. Participants

The inclusion criteria were parents who were raising their children in a multilingual environment, who were living in Spain, either in a bilingual or a monolingual autonomous community. The children were aged between 5 and 10 years and could present either typical development or a developmental disorder. We wanted to explore the parental views of both of these groups to help us to contextualize the perspectives of parents who seek professional help for their children. The families could be from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, including parents who spoke one or more of the regional languages of Spain, foreign languages, or parents who spoke Spanish but chose to expose their children to an additional language.

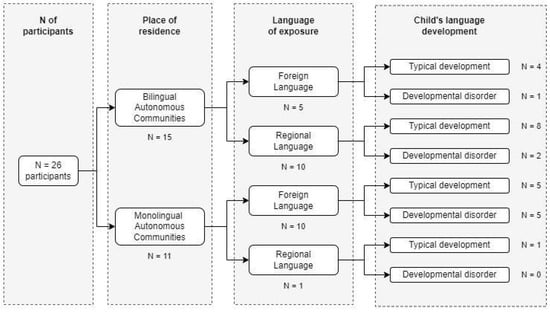

Since we aimed for maximum variation in the sample to capture a range of perspectives, we recruited participants who met the following inclusion criteria: the place of residence of the families (bilingual vs. monolingual autonomous communities in Spain1), the main language the child was exposed to besides Spanish (foreign vs. regional languages) and the presence or absence of developmental disorders. Figure 1 presents a distribution of the participants of this study according to the previous criteria.

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants according to inclusion criteria.

In relation to Figure 1, we made the assumption that the families who lived in bilingual communities were considered to have a natural exposure to the regional languages (even though they might not always use it actively), so the parents whose children were regularly exposed to a foreign language and lived in a bilingual community were placed in the ‘Bilingual Autonomous Community --> Foreign Languages’ branch. Apart from that, parents who reported that their children presented a language delay that eventually stabilized were placed in the ‘Typical development’ section.

The families were recruited using snowball sampling through the researchers’ personal contacts (acquaintances who might fit the inclusion criteria), academics and/or clinicians specialized in linguistics and speech–language therapy, as well as by asking the families who enrolled in this study to contact other families similar to them. Schools, associations and speech–language therapy practitioners in different regions of Spain were also asked to distribute information leaflets. Additionally, a website with information about this study and how to participate was created and distributed among the stakeholders listed, and it was also shared on social media platforms (i.e., LinkedIn and Facebook groups about multilingual families in Spain). Information about this study and its website were also emailed to the administrators of blogs, forums and Instagram accounts that shared information about raising multilingual children in Spain.

We recruited 26 parents (Table 1). Only one parent in each family participated in this study. The number of participants was initially determined based on the guidance of Terry et al. (2017) for a project of this size. With regards to the language development of the children, as reported by the participating families, 35% of them had at least one child with a developmental disorder. Among those families, 4 parents declared that their child was formally diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), 3 with developmental language disorder and 2 with dyslexia (one of them comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). The rest of the families (65%) did not declare any diagnosis in relation to the development of their children.

Table 1.

Profiles of families according to the place of residence, languages spoken and the children’s language development.

2.2. Data Collection

The data were collected using semi-structured online interviews. These were conducted by the first author via video-call to facilitate the participation of parents based in geographically dispersed areas (Archibald et al. 2019). The interviews were conducted in Spanish, as it was the common language between the families and the researcher. The interviewer asked the participants to self-assess their language skills through screening questions (e.g., “Do you feel comfortable in all the languages you speak?”) (Premji et al. 2020). To address any potential linguistic barriers, the participants were encouraged to code-switch and take time to answer.

A topic guide was designed, which included open-ended questions to obtain in-depth information about each one of the families. First, there were questions exploring the parents’ own sociolinguistic background and linguistic dynamics in their community context, followed by questions about the children’s language exposure and development as multilinguals. The section about the children was divided into four parts: the parent’s views, experiences and priorities when raising multilingual children, and the languages that children were exposed to in their setting; possible concerns about the children’s language development; advice received from professionals (e.g., speech–language therapists, teachers, school counselors, psychologists, etc.); and views about and experiences in the children’s past and current school settings. The interview ended with a summary of the topics discussed. The interviewer followed an iterative approach by taking notes during the interview about issues brought up by parents that were not in the original topic guide. These issues were included in the topic guide for subsequent interviews. The mean length of the interviews was 1 h 32 min [55′–2h13′]. The interviews were recorded in audio and video (Archibald et al. 2019), and were transcribed in two steps: first, we used Sonix.ai to go through the audio and convert it into text, and then we edited the text generated by the program in collaboration with speech–language therapy students who volunteered. The analysis of the interviews was carried out during and after the transcription process.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2022). The aim of the analysis was to identify patterns across the dataset, leading to the generation of themes that would represent the data in an interpretative manner. The interviews were analyzed in the original language to prevent misrepresenting the participants’ experiences during the analysis (Al-Amer et al. 2015). Excerpts were translated into English for this paper.

The analysis was conducted by the first author by working through the six-phase process for reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2022). During phase 1 (familiarization with the data), the researcher revised the notes taken during the interviews and read the transcriptions several times. In phase 2 (coding the data), the researcher inductively coded segments related to the research questions. In phase 3 (generating initial themes), the researcher identified shared patterns across the dataset, adding a descriptive name. The first and third authors worked collaboratively from the 4th phase (developing and reviewing themes) to assess whether the themes were grounded in the dataset and making modifications. In phase 5 (refining, defining and naming themes), the themes were re-evaluated to provide an interpretation that told a story about the data. The researchers went back and forth between the 4th and 5th phases several times. The last phase (writing up) began in parallel with phase 4, when the three authors collaborated to find consensus about the analytic narrative.

Reflexivity in the Context of This Research

Reflexive thematic analysis inherently calls for self-reflection, placing the researcher as an active agent during the analysis by interacting with the data and being aware of their own subjectivity and influence on the research. For that reason, we opted to use the first person in this section.

In this study, the authors’ perspectives are framed as insider/outsider (Lyons et al. 2022, p. 282). All of the authors are speech and language therapists who share an interest in multilingualism. In this case, the first author was an insider, as she is originally from Galicia (one of the bilingual regions of Spain) and identifies as a multilingual. This may have helped in bonding with some participants during the interviews but might have also biased some responses because participants may have assumed that the researcher was already familiar with the issues discussed. The second author was also from Spain but was born and raised in Madrid, which is a monolingual yet culturally diverse region. The third author would be considered an outsider, as she is from Galway (Ireland). To address our potential biases, when designing the topic guide, we formulated open questions. In the interviews, the first author assured the participants that there were no right or wrong answers and encouraged them to share views that might align or deviate from those of the interviewer. In the analysis, we checked our interpretations with each other and ensured that the themes were grounded in the data.

3. Results

We identified two themes: complexities regarding identity and belonging and balancing the power of advice and parental agency. These themes illustrated that each family presented with a unique set of circumstances and experiences that shaped their preferences and language choices for their specific family context.

3.1. Theme 1: Complexities Regarding Identity and Belonging

The data highlighted the complexity of what being multilingual meant, living in Spain; for example, some parents were born in a different country and were now living in Spain, where they had to juggle their heritage language along with the dominant language (Spanish) and/or a regional language (e.g., Catalan), depending on where they lived. There were other families where the parents were from Spain and had to make decisions about their children learning the dominant language in addition to another language, which could be a foreign and/or regional language. The complexity was also illustrated by the range of choices that families made in relation to language choice in the context of having children with typical development or developmental disorders.

This theme represented the parents’ views about language choice in relation to their children’s identity and sense of belonging in their multicultural context. This theme was separated into two subthemes to represent the complexity of family contexts and the range of experiences: finding balance between the local and heritage language(s) and culture(s) and awareness of stigma and opportunities.

3.1.1. Subtheme 1: Finding Balance between the Local and Heritage Language(s) and Culture(s)

This subtheme included the range of preferences reported by parents of children with and without developmental disorders in terms of identity construction, considering the maintenance of their heritage language and culture in the place where they lived.

We identified different patterns in their choices. In some cases, parents prioritized the dominant language over their heritage language to achieve a sense of belonging in their community. For example, a Serbian mother had made the decision for her child to learn the dominant language (Spanish) over her heritage language, so that the child (and herself) would fit better into their local community. For this parent, transmitting her language was challenging in a context where, in her view, there was not enough support of the Serbian language.

‘I need to make an effort [in Serbian], I have to think beforehand what I want to say. […] [in Serbia] I would be in contact with people who also speak the language. But here, in an environment where everyone speaks Spanish, I couldn’t do it. […] Sure, in a hypothetical situation where they could only speak one language for the rest of their lives, [I would choose] the one of the country where they are born. Because they would not be able to communicate otherwise’.(F18)

In other cases, some parents chose to use the regional language(s) with their children to preserve the local identity. This included families who were living both in bilingual and monolingual autonomous communities, and it was especially seen in families from Galicia. For example, a mother had learned Dutch as her childhood language but switched to Galician as her dominant language. She made the decision for her child to learn the language of the region because she had lived in numerous places throughout her life and wanted her children to have a connection to Galicia. She also tried to transmit part of her Dutch identity to her children through cultural traditions and foods, with less emphasis on the language, as she did not feel comfortable enough to do so.

‘We celebrate Dutch traditions, we also cook what my mother used to make […] to maintain as much contact with the Dutch culture and language as possible considering… my limitations for not speaking it 100%. […] [the Galician language] was important for me, maybe because I’ve never had “my childhood place” and I was a bit jealous of… people who belonged to one place. […] I like that my kids have… the feeling of belonging to a place, and I believe that the language is essential there’.(F12)

A Galician mother, who was raising her child in Madrid, decided to speak to her child in Galician, as she had a strong sense of identity with her roots and wanted to transmit this sense of belonging to her child.

‘It was obvious to me that no matter where I lived, I would speak to my daughter in Galician. […] So she can understand, well, the language and culture of… where she comes from, where I come from… and share an emotional bond with each other… through that language’.(F11)

Additionally, some parents made efforts to transmit both the dominant and the heritage languages to their children. They were aware of the importance of their children fitting in their local context while also maintaining a sense of belonging to their roots. For example, there was a mother, also from Galicia, who had adopted a child from China who was subsequently diagnosed with ASD. The mother subconsciously started to speak Galician to him because it is the language she felt most attached to. However, she also chose to enroll her child in Mandarin Chinese lessons to provide continuity for him in terms of exposure to his heritage language and culture.

‘Let’s see, I went to China to pick up my child—he was adopted in China. When I arrived there, it was something unconscious, I mean, I wasn’t thinking about it, but I started to speak to him in Galician because it’s… it’s my emotional language. […] We, well, when he left China, in order to not make it too abrupt for him, we continued to play Chinese music, we took him to Mandarin lessons... Everything was like “there’s no breakage”, well there would be anyway, right? But kinder. We wanted to make it as easy as possible’.(F17)

Some parents reported that they did not feel comfortable about their identity and heritage language due to negative experiences in their country of origin. In this case, a mother of a child with ASD decided not to use her heritage language (Romanian) with her child and speak in English to him, as she developed a stronger attachment to that language over the years.

‘English has become like my mother tongue. […] I feel it closer to my heart than Romanian. […] So when my child was born I started to speak to him in Romanian and I was not comfortable, […] so after three months I dropped it and started to speak in English’.(F15)

In contrast, a father from Germany explained he was not comfortable with his German identity because of generational traumas but chose to maintain that language with his children.

‘Now we continue speaking in German, and they even speak in German between them. I like that. I like it so much when they speak in German between them, because it’s like a complicity that nobody but them can share. […] Actually, I wanted to “de-Germanize” myself, like other compatriots. […] There are family constellations and generational traumas about Nazism and so on. […] Yes, and everyone processes it their own way’.(F23)

These data illustrate the complexities regarding language choice, identity and belonging, and the unique circumstances and experiences that shaped the parents’ preferences and language choices.

3.1.2. Subtheme 2: Awareness of Stigma and Opportunities

This subtheme included data about how parents, consciously or unconsciously, wanted their children and themselves to be perceived, depending on the language that they used. They were aware of the prestige and stigma associated with language choice, which shaped their views towards which languages they considered would provide better opportunities for their children’s future in terms of thriving in social, academic or occupational domains.

For example, a mother from Bulgaria, whose child was exposed to Bulgarian, Spanish and English, said she would choose English over Bulgarian because it would bring more advantages to her child, even though that decision would hurt her because Bulgarian was part of her identity.

‘I give way more value to English because it opens you many doors nowadays. Wherever you go you’ll need English. Spanish too, because nowadays, if you speak English or Spanish, the world is yours. […] So I don’t give much value to Bulgarian. It hurts me that my son doesn’t speak Bulgarian because it’s my mother tongue. I’m Bulgarian, but I don’t give much value to it. Why? Because workwise and at personal levels, it won’t help him much’.(F2)

In contrast, a mother from Germany had an experience related to the social praise of some languages over others, where she received compliments for speaking German with her child. She disagreed with the stigma associated with languages of perceived lower prestige.

‘I used to feel like people looked at me with disapproval. That was my perception. […] I had an odd experience once: I was talking to my child in German, […] and someone told me “Where are you from?” “Germany” “Oh Germany, that’s great” they’d say, “I thought you were Romanian”. So for me that was… […] maybe they were thinking “How bad they’re speaking Romanian”. Do you know what I mean? […] They don’t give value to it. But when it’s a German… [they do] and I think that’s a bit sad’.(F4)

This same mother was hopeful that her child might not have to experience discrimination for his language (German), which may have been the case if she spoke a language that was perceived as less valued.

‘But I am grateful that I’m not Romanian in terms of… well, I haven’t suffered… you know? It would be more difficult, and I put myself in the shoes of parents from other nationalities that may not be as valued, and implementing bilingualism must be very difficult’.(F4)

Some parents considered that multilingualism would be useful and allow their children to travel and integrate in different milieus regardless of the languages spoken. For example, a mother from Mallorca (Balearic Islands) discussed the advantages and disadvantages of speaking several languages.

‘The disadvantages would be its great limitations, and the advantages would be that there are no limits. […] The more languages you have, the more doors will open for you to the world, both in work and leisure contexts. But if you have less languages, you will be limited. If you only speak Balearic Catalan, you won’t move from here’.(F22)

In summary, this subtheme illustrated how parents’ decisions about language choice were shaped by their perceptions about the status of languages and their wish for their children to have opportunities now and in the future.

3.2. Theme 2: Balancing the Power of Advice and Parental Agency

This theme included data related to how advice received influenced parents’ decisions about language choice. In some instances, parents accepted this advice, and in other cases, they exercised agency by not adhering to the advice. Not all the families received explicit advice.

This theme included the different recommendations that parents received from professionals, and how that advice influenced language choices in their household. In this context, the term professionals referred to teachers, headmasters, healthcare professionals, psychologists and speech–language therapists. In some cases, professionals recommended dropping one language to prevent children from experiencing language delays or worsening their developmental disorders. In some instances, they followed the advice, and although the parents perceived these professionals as holding power, in other cases they exercised agency by not adhering to it.

For example, a Bulgarian parent who lived in Madrid followed a professional’s advice. She had been advised by the child’s nursery teacher and headmaster to drop Bulgarian to enable the child to catch up with Spanish, and she was also advised to enroll her child in the bilingual English–Spanish group. She had some concerns about the child’s language development and followed the advice to drop Bulgarian and start the English classes. She later regretted this decision because she had subsequently studied speech-language therapy and was now aware that being multilingual does not hinder children’s development.

‘The thing is that our son was very young when he started kindergarten. He was 3 months old. So when he was one… he wouldn’t respond to what he was said, right? He wouldn’t obey. So I was worried and asked the kindergarten teacher. […] She commented that the child “does always obey” and said we should try to speak in Spanish and hold our language back. […] So we as a family decided to speak to him in Spanish only so he could catch up with his peers. […] Then the teacher suggested we enroll him in a bilingual English-Spanish class, and we did. […] I think our mistake was that, instead of enrolling him in that English class, we should have started to introduce Bulgarian again’.(F2)

On other occasions, parents exercised agency by not following the advice of dropping a language. For instance, one mother of a child with developmental language disorder, who lived in Madrid, reported that she was advised by healthcare professionals to only use the dominant language to avoid confusing her child; she was not convinced about this advice.

‘I think that in most of the places we visited we were told “no, no, of course. You have to speak only in Spanish, because otherwise your son will be even more confused”. Um… I don’t know… I have my doubts about that. […] We consider that he can receive both languages without a problem’.(F16)

Nonetheless, some professionals encouraged parents to use the heritage language at home. For example, a Galician parent, who lived in Madrid, reported that she always received positive comments from professionals about raising her child as a multilingual.

‘The teacher was supportive about the book in Galician […] that I should speak in Galician to him. […] In our case, full support. […] I mean, I never had a negative experience like “no, don’t talk to him [in Galician] because you will interfere”. Not at all. […] It is an environment that cares a lot’.(F11)

There were nuances regarding professional advice, depending on where the family lived. Some parents considered that attitudes towards a multilingual upbringing might be more positive in the bilingual communities, as speaking several languages is the norm in those regions. For example, a Catalan mother of a typically developing child talked about the normalization of multilingualism in those communities.

‘Here it’s super normal that children have one parent who speaks Catalan and the other speaks Spanish. It is the most… it’s very common. So I think that it’s not, like it’s not a weird thing or something that would make a difference. It’s not something like “oh, you speak two languages, so I recommend you do this and that”, no, because it’s very common’.(F5)

This theme captured the influence that advice might have on parental choices about which language(s) to use when rearing their children, and the ways in which the parents responded to this advice.

4. Discussion

This study explored the language views and priorities of parents of multilingual children, including those whose language was typically developing and those with a developmental disorder, in terms of language choice and use in their household. In this qualitative study, we used online semi-structured interviews. The data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2019). We identified two themes: complexities regarding identity and belonging and balancing the power of advice and parental agency. We also identified two subthemes within the first theme: finding balance between the local and heritage language(s) and culture(s) and awareness of stigma and opportunities.

The findings will be discussed in relation to the themes, this study’s limitations, future research and implications.

The overall findings in this study accentuate the complexities of a multilingual rearing, illustrating possible challenges parents might face regarding decisions about language choice in their households. Our findings suggest that choices regarding language use and maintenance might be influenced by parents’ own views and external influences. Our findings align with previous studies discussing the complexities of language ideologies in Greek-speaking families in relation to the preservation of their linguistic and ethnic identities (Kostoulas and Motsiou 2022), especially when there is a clash between parents’ views and the ideologies of the locals in the country of residence (Kirsch 2012).

Regarding the first theme, ‘complexities regarding identity and belonging’, our findings illustrate the relationship between language and identity, in relation to the choice of languages in multilingual households. Identity is negotiated through the language, culture and values parents want to associate with, as well as through their actions in terms of how they want to present themselves and their children to meet their goals (Fuentes 2020). The results suggest that parents have an overall appreciation for their home languages, cultural practices, and multilingualism in general, reporting positive views regarding the role of languages in their children’s identity construction and sense of belonging, regardless of the presence or absence of a developmental disorder. This relates to the findings of Hampton et al. (2017), who discussed the parental attachment to their heritage language(s) and culture(s) in multilingual families of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Similarly, Berardi-Wiltshire (2017) reported that Spanish-speaking parents in New Zealand highlighted the affective value assigned to the Spanish language, which resonates with our findings in relation to the home language providing a sense of self, meaningful family ties and overall well-being. However, our findings present a range of language choices at home when parents needed to balance the home and dominant languages in their respective locations. Previous research has shown similar findings, where parents with different linguistic backgrounds reported having an attachment to their languages, but their practices may not always align with those views (Gharibi and Seals 2020; Kwon 2017). In our study, parents sometimes prioritized the development of the dominant language over the heritage language(s). This finding aligns with the results of Akgül et al. (2019), suggesting that parents consider that a “native-like” competence in the dominant language is necessary to better adapt to the country. Our findings also suggest that the choice of languages might also be linked to the status and prestige associated with them. This resonates with the findings of Berardi-Wiltshire (2017), who described how Chinese-born and Spanish-speaking parents might choose the languages spoken at home according to their value as international languages. The parents in our study were aware of the stigma and opportunities associated with some languages over others, which might have influenced their determination to transmit their languages and identities to their children. Researchers have also documented the relationship between stigma and language maintenance in different linguistic contexts; for example, through the clashes between the Persian and Azerbaijani languages in Iran (Mirvahedi 2021), the status of the English language in Korea (Seo 2021) or the influence that language hierarchy may have in the choice of languages in China (Curdt-Christiansen and Wang 2018).

In relation to the second theme, ‘balancing the power of advice and parental agency’, the results highlighted the power that explicit advice from a professional could have on families’ choice of languages, leading to parents reflecting about their priorities. Our findings are consistent with previous research, which showed that advice from professionals such as teachers and speech–language therapists can influence parents’ beliefs and decisions regarding multilingualism and home language maintenance (Bezcioglu-Göktolga and Yagmur 2018; Mirvahedi and Hosseini 2023). Other researchers have also discussed the impact of advice from others (non-professionals). For example, some argue that attitudes from friends, family and the local community may play a role in home language maintenance (Gharibi and Seals 2020). Nakamura (2019) argued that parents’ confidence in their decisions is strengthened or weakened, based on their support system. The manner in which parents adhered to or opposed the advice reflects their empowerment regarding decision-making in educational/clinical contexts. Parents’ empowerment and confidence could be enhanced through family-centered practices (Nachshen 2005). The views of our participants in relation to the advice received suggest that the place of residence might play a role in the attitudes people hold towards languages and multilingualism. These views could be related to the language education and policies in bilingual autonomous communities in Spain. Researchers such as Lasagabaster (2005) discussed relationships between attitudes towards the languages of exposure and education, depending on the sociolinguistic context and the speakers’ language competence. However, even though the residents of those communities might be used to multilingualism, there is still a linguistic prejudice associated with members of visible minority groups (Rodríguez-García et al. 2021).

Our findings indicate that even though there is a diversity in parental choices and the advice received, there seems to be remaining traces of the misconceptions around multilingualism, especially when children present with developmental disorders (Cioè-Peña 2021; Moore and Pérez-Méndez 2006), and the stigma associated with languages perceived as having lower status (Schroedler et al. 2022).

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

It is important that the findings of this study be interpreted in the context of its strengths and limitations.

One of the strengths of this research is that it included participants from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This helped understand the different views and experiences of families who were raising children, with and without developmental disorders, in a multilingual context in Spain. However, there was a lack of representation of families from non-European countries. In addition, there was a lack of heterogeneity in the socioeconomic profiles of the participants due to the recruitment method used, which limited the access to families of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Secondly, we used semi-structured online interviews to gather in-depth data. The duration of the recordings totaled 39 h 52 min across the 26 interviews, providing rich data. Nonetheless, the length of the interviews might have influenced the willingness of parents to participate, as some of them reported having a busy schedule. Having three authors involved in the analysis enhanced the rigor of this study.

Additionally, we interviewed only one parent per family. However, it would be of interest to reflect the views of both parents to have a deeper understanding of their perspectives and decisions regarding language choice in the household.

A limitation of this study was that the interviews were conducted only in Spanish, which may have influenced the quality of the answers provided by the parents whose first language was not Spanish (Squires et al. 2020). These language constraints also restricted which parents could participate in this study. However, it was not possible to interview all parents in their first language with the resources available at the time of the interviews. In addition, translating the interviews might have compromised the richness of the data (Lopez et al. 2008). Therefore, the authors kept the interviews in Spanish until the analysis was finished and only translated them to provide excerpts for this paper.

On a final note, we consider the range of insider/outsider perspectives of the authors (Lyons et al. 2022) as a strength, as it enabled us to challenge assumptions and ensure that the analysis was grounded in the data.

4.2. Future Research and Implications

Further research is needed that includes families from a wider range of linguistic, cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds to facilitate a deeper understanding of their perspectives. It would also be of interest to include the views of all the family members that may play a role in the language dynamics and choices within the household.

Finally, this study has clinical implications. The themes identified illustrate the complex situations parents face when rearing multilingual children. First, this qualitative study illustrates the variability in parents’ views regarding the transmission of their linguistic and cultural identities to their children. We believe that speech–language therapists and other stakeholders would benefit from understanding these complex and nuanced perspectives. These findings highlight the importance of listening to parents and tailoring practices to the needs of each unique family. For example, for some families, the use of certain languages might not be among the priorities of parents, for different reasons. It is important that professionals listen to parents and respect their wishes. This research also highlights the importance of culturally responsive practices that prioritize inclusion and embrace diversity.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study illustrate the complexities involving decisions about language choice in multilingual families in the linguistic context of Spain. The parents in our study seem to prioritize the languages to use with their children depending on their own views, along with the influence of external attitudes. This is consistent with Bucholtz and Hall’s (2005) inter-relational concept of identity, where a person builds and negotiates their identity through interaction in different contexts.

This research highlights the importance of a person-centered approach that is culturally responsive, where the professional takes into consideration the cultural and linguistic context, needs and priorities of multilingual families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.; Methodology, P.B. and R.L.; Validation, R.L. and S.N.; Formal Analysis, P.B. and R.L.; Investigation, P.B.; Resources, P.B., S.N. and R.L.; Writing—original draft, P.B.; Writing—review & editing, P.B., R.L. and S.N.; Visualization, P.B., R.L. and S.N.; Supervision, S.N. and R.L.; Project Administration, P.B. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology of the Complutense University of Madrid (Ref. 2020/21-034).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to ethical, legal and privacy issues related to the participants personal data. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The COREQ checklist can be found here: DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.25111376.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who participated in this study and the volunteer students who contributed to the transcription of the interviews. We also thank family, friends and colleagues for assistance in distributing information about this study and the project’s website. We acknowledge the use of Sonix.ai to generate the first draft of the transcriptions, prior to a manual revision and translation of excerpts for this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | In this study we considered the status of co-officiality of languages to determine the classification of autonomous communities into bilingual or monolingual. |

References

- Akgül, Esra, Dila Yazıcı, and Berrin Akman. 2019. Views of parents preferring to raise a bilingual child. Early Child Development and Care 189: 1588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amer, Rasmieh, Lucie Ramjan, Paul Glew, Maram Darwish, and Yenna Salamonson. 2015. Translation of interviews from a source language to a target language: Examining issues in cross-cultural health care research. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 1151–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, Mandy M., Rachel C. Ambagtsheer, Mavourneen G. Casey, and Michael Lawless. 2019. Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: Perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1609406919874596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi-Wiltshire, Arianna. 2017. Parental ideologies and family language policies among Spanish-speaking migrants to New Zealand. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research 23: 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezcioglu-Göktolga, Irem, and Kutlay Yagmur. 2018. The impact of Dutch teachers on family language policy of Turkish immigrant parents. Language, Culture and Curriculum 31: 220–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis. A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, Mary, and Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies 7: 585–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioè-Peña, María. 2021. Raciolinguistics and the education of emergent bilinguals labeled as disabled. The Urban Review 53: 443–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Ronald B., Jr., Darcey K. deSouza, Juan Bao, Hua Lin, Sumeyra Sahbaz, Kimberly A. Greder, Robert E. Larzelere, Isaac J. Washburn, Maritza Leon-Cartagena, and Alma Arredondo-Lopez. 2021. Shared language erosion: Rethinking immigrant family communication and impacts on youth development. Children 8: 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan, and Weihong Wang. 2018. Parents as agents of multilingual education: Family language planning in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum 31: 235–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, Ronald. 2020. Transnational Sri Lankan Sinhalese family language policy: Challenges and contradictions at play in two families in the US. Multilingua 39: 475–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibi, Khadij, and Corinne Seals. 2020. Heritage language policies of the Iranian diaspora in New Zealand. International Multilingual Research Journal 14: 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, Helen, and Sharynne McLeod. 2012. Multilingual speech and language development and disorders. In Communication Disorders in Multicultural and International Populations. St. Louis: Elsevier, pp. 120–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, Sarah, Hugh Rabagliati, Antonella Sorace, and Sue Fletcher-Watson. 2017. Autism and bilingualism: A qualitative interview study of parents’ perspectives and experiences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 60: 435–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmlund, Maria, Lars Witell, and Anders Gustafsson. 2020. Getting your qualitative service research published. Journal of Services Marketing 34: 111–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Katie, Jenny Gibson, and Napoleon Katsos. 2021. Parental perceptions and decisions regarding maintaining bilingualism in autism. Journal of autism and Developmental Disorders 51: 179–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijalba, Elizabeth. 2016. Hispanic immigrant mothers of young children with autism spectrum disorders: How do they understand and cope with autism? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 25: 200–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2023. España en Cifras 2023. Madrid: INE. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Christina D. 2022. Bilingual Proficiency Development and Translanguaging Practices of Emergent Korean-English Bilingual Children in Korea. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 13: 1156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, Claudine. 2012. Ideologies, struggles and contradictions: An account of mothers raising their children bilingually in Luxembourgish and English in Great Britain. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatte, Inge S., Manon Bloemen, Annemieke de Groot, Tina C. Mantel, Marjolijn Ketelaar, and Ellen Gerrits. 2023. Collaborative working in speech and language therapy for children with DLD—What are parents’ needs? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 59: 340–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnert, Kathryn, Kerry Danahy Ebert, and Giang Thuy Pham, eds. 2021. Intervention with bilingual children with language disorders. In Language Disorders in Bilingual Children and Adults, 3rd ed. San Diego: Plural Publishing, pp. 189–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kostoulas, Achilleas, and Eleni Motsiou. 2022. Family language policy in mixed-language families: An exploratory study of online parental discourses. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25: 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Jungmin. 2017. Immigrant mothers’ beliefs and transnational strategies for their children’s heritage language maintenance. Language and Education 31: 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, David. 2005. Attitudes towards Basque, Spanish and English: An analysis of the most influential variables. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 26: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, David. 2007. Language use and language attitudes in the Basque Country. In Multilingualism in European Bilingual Contexts: Language Use and Attitudes. Edited by D. Lasagabaster and A. Huget. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Boh Young. 2013. Heritage language maintenance and cultural identity formation: The case of Korean immigrant parents and their children in the USA. Early Child Development and Care 183: 1576–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Griselda I., Maria Figueroa, Sarah E. Connor, and Sally L. Maliski. 2008. Translation barriers in conducting qualitative research with Spanish speakers. Qualitative Health Research 18: 1729–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Rena, Emily Armstrong, Marie Atherton, Karen Brewer, Anne Lowell, Ḻäwurrpa Maypilama, Wiebke Scharff Rethfeldt, and Jennifer Watermeyer. 2022. Cultural and Linguistic Considerations in Qualitative Analysis. In Diving Deep into Qualitative Data Analysis in Communication Disorders Research. Havant: J&R Press, pp. 277–318. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, Viorica, and Sayuri Hayakawa. 2021. Measuring bilingualism: The quest for a “bilingualism quotient”. Applied Psycholinguistics 42: 527–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi. 2021. Examining family language policy through realist social theory. Language in Society 50: 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi, and Mona Hosseini. 2023. Family language policy in retrospect: Narratives of success and failure in an Indian–Iranian transnational family. Language Policy 22: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirvahedi, Seyed Hadi, and Rasoul Jafari. 2021. Family language policy in the city of Zanjan: A city for the forlorn Azerbaijani. International Journal of Multilingualism 18: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Susan M., and Clara Pérez-Méndez. 2006. Working with linguistically diverse families in early intervention: Misconceptions and missed opportunities. In Seminars in Speech and Language. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, vol. 27, pp. 187–98. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Fernández, Francisco. 2015. La importancia internacional de las lenguas. In Observatorio de la Lengua Española y las Culturas Hispánicas en los Estados Unidos. Instituto Cervantes de la FAS. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Nachshen, Jennifer S. 2005. Empowerment and families: Building bridges between parents and professionals, theory and research. Journal on Developmental Disabilities 11: 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Janice. 2019. Parents’ impact belief in raising bilingual and biliterate children in Japan. Psychology of Language and Communication 23: 137–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, Anik. 2019. Política lingüística familiar. O papel dos proxenitores pro-galego na transmisión interxeracional. Estudos da Lingüística Galega 11: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, Silvia, Eva Aguilar-Mediavilla, Lidia Rodríguez, and Barbara T. Conboy. 2020. Competencias profesionales para el trabajo con población multilingüe y multicultural en España: Creencias, prácticas y necesidades de los/las logopedas. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología 40: 152–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowski, Michał B., and Aleksandra Bator. 2018. Perceived effectiveness of language acquisition in the process of multilingual upbringing by parents of different nationalities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21: 647–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, Elizabeth D. 2016. Supporting the home language of bilingual children with developmental disabilities: From knowing to doing. Journal of Communication Disorders 63: 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, Elizabeth D., Lisa M. Bedore, and Alejandro Granados Vargas. 2023. Exploring assumptions of the bilingual delay in children with and without developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 66: 4739–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peristeri, Eleni, Eleni Baldimtsi, Margreet Vogelzang, Ianthi Maria Tsimpli, and Stephanie Durrleman. 2021. The cognitive benefits of bilingualism in autism spectrum disorder: Is theory of mind boosted and by which underlying factors? Autism Research 14: 1695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premji, Stephanie, Agnieszka Kosny, Basak Yanar, and Momtaz Begum. 2020. Tool for the meaningful consideration of language barriers in qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research 30: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramallo, Fernando. 2012. El Gallego en la familia: Entre la producción y la reproducción. Revista Internacional de Filología 53: 167–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ramallo, Fernando. 2022. A enquisa sociolingüística das linguas minoradas: Diagnóstico e conciencia comunitaria. Mondo Ladino 45: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, Dan, Miguel Solana-Solana, Anna Ortiz-Guitart, and Joanna L. Freedman. 2021. Linguistic cultural capital among descendants of mixed couples in Catalonia, Spain: Realities and inequalities. In The Boundaries of Mixedness. London: Routledge, pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, Margarete. 2000. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health 23: 334–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalley, Andrea C., and Susana Eisenchlas, eds. 2020. Social and affective factors in home language maintenance and development: Setting the scene. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development: Social and Affective Factors. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 18, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schroedler, Tobias, Judith Purkarthofer, and Katja F. Cantone. 2022. The prestige and perceived value of home languages. Insights from an exploratory study on multilingual speakers’ own perceptions and experiences of linguistic discrimination. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Youngjoo. 2021. Parental Language Ideologies and Affecting Factors in Bilingual Parenting in Korea. English Teaching 76: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, David Ariel, Jenny L. Gibson, and Wendy V. Browne. 2022. “It’s Like Stealing What Should be Theirs.” An Exploration of the Experiences and Perspectives of Parents and Educational Practitioners on Hebrew–English Bilingualism for Jewish Autistic Children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 52: 4440–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Navin Kumar, Shaoan Zhang, and Parwez Besmel. 2012. Globalization and language policies of multilingual societies: Some case studies of South East Asia. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada 12: 349–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, Josep, and Anastassia Zabrodskaja. 2017. New spaces of new speaker profiles: Exploring language ideologies in transnational multilingual families. Language in Society 46: 547–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, Allison, Tina Sadarangani, and Simon Jones. 2020. Strategies for overcoming language barriers in research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 76: 706–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surrain, Sarah, and Gigi Luk. 2019. Describing bilinguals: A systematic review of labels and descriptions used in the literature between 2005–2015. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 401–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, Gareth, Nikki Hayfield, Victoria Clarke, and Virginia Braun. 2017. Thematic analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Edited by C. Willig and W. Stainton Rogers. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Allison, Peter Sainsbury, and Jonathan Craig. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Amelia. 2020. Identity in home-language maintenance. In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development: Social and Affective factors. Edited by A. Schalley and S. Eisenchlas. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 18, pp. 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Sixuan, and Xuesong Gao. 2021. ‘Home away from home’: Understanding Chinese parents’ ideological beliefs and involvement in international school students’ language learning. Current Issues in Language Planning 22: 495–515. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).