Abstract

In this study, we document the coordination of eye gaze and manual signing in a local sign language from Nebaj, Guatemala. We analyze gaze patterns in two conversations in which signers described the book Frog Where Are You to an interlocutor. The signers include a deaf child who narrated the book to a hearing interlocutor and her grandfather, who is also deaf, as he described the same book to his hearing grandson during a separate conversation. We code the two narratives for gaze target and sign type, analyzing the relationship between eye gaze and sign type as well as describing patterns in the sequencing of eye gaze targets. Both signers show a strong correlation between sign type and the direction of their eye gaze. As in previous literature, signers looked to a specialized medial space while producing signs that enact the action of characters in discourse in contrast to eye gaze patterns for non-enacting signs. Our analysis highlights both pragmatic–interactional and discursive–narrative functions of gaze. The pragmatic–interactional use of gaze primarily relates to the management of visual attention and turn-taking, while the discursive–narrative use of gaze marks the distinction between narrator and character perspective within stretches of narration.

1. Introduction

If you look closely, we talk with our eyes all the time. Language users manage eye gaze strategically in conversations to achieve multiple interactional goals including taking a turn, ending a turn and letting someone else take the floor, pointing out locations and objects, “holding” a thought, or acting out characters (Degutyte and Astell 2021). Gaze coordination between language users has historically been identified and described as a core feature of human social interaction (e.g., Darwin 1872). However, the question of “universal” versus culturally specific patterns of gaze behavior in interaction remains open. Research in the tradition of Conversation Analysis (CA) has often focused on gaze patterns during question–answer sequences and suggests that some behaviors may be culturally specific while others are more likely to be shared cross-linguistically (Rossano et al. 2009). In their analysis of question–answer sequences across three spoken languages, some patterns were found to be more culturally specific, varying more across languages (e.g., use of gaze to ‘point’)—and others more universal, exhibiting less variability across languages (e.g., questions producers generally looked more at their interlocutor than the reverse). Rossano et al. (2009) point out that in order to understand universal versus culturally-ly specific dimensions of gaze, we must engage in close analysis of the coordination of gaze and language—one dimension of the “coexpressive” nature of interaction—in conversations from a wide range of linguistic communities. This paper adds to the growing literature on gaze patterns in interaction with a study of gaze and narrative in a small local sign language from Guatemala. Our data thus expand on prior work in two ways: first by extending the modality and type of languages in which gaze behavior is documented to include local sign languages and second, by documenting gaze in a different genre, shifting from question–answer sequences to longer narrative descriptions of scenes.

Local sign languages, sometimes referred to as “micro-community sign languages” (Braithwaite 2020) or “nucleated sign networks” (Reed 2022) are used around the world by small groups of people with one or more deaf members. Their time depth varies and can be difficult to establish (Hou and de Vos 2022; de Vos and Pfau 2015; Braithwaite 2020), but many of these sign languages have some degree of intergenerational transmission if there is inherited deafness within families. These languages are sociologically similar to other minority languages in some ways, for example, many hearing signers will be bilingual in one or more spoken languages and the sign language, but also distinct from minority spoken languages in their distribution, use, and vitality (Webster and Safar 2020). Users of local sign languages are also sometimes distinguished from ‘homesigners’, individual deaf signers who have few signing interlocutors and no access to input in the form of a national or local sign language.

Deaf signers offer a unique perspective for understanding core features of human interaction and coexpressivity because they have highly variable interactions with hearing interlocutors who may or may not be proficient or fluent users of the sign language or willing participants in signed interactions (Green 2022; Graif 2018). Shared comprehension and engagement cannot always be taken for granted in these exchanges: in a study of deaf homesigners in Nicaragua, Carrigan and Coppola (2017) found that their hearing communication partners often did not understand homesign utterances isolated from their original context. As Green (2022) and Graif (2018) have noted, there may exist a particular kind of precarity to many of these exchanges, and negotiating the pragmatics of conversation may be particularly challenging. As a result, we might predict distinct interactional norms and gaze patterns in local sign languages.

In addition to providing documentation of gaze patterns in local sign languages, which have not been extensively studied elsewhere in the literature on eye gaze (though see Haviland 2020 for one example), this study explores gaze behavior in the context of a different discourse genre, leading to one of our primary theoretical questions about the diversity of functions for gaze in conversation. Much of the research on gaze patterns in question–answer sequences focuses on the uses of gaze to manage pragmatic, interpersonal dimensions of conversation like initiating and exchanging turns. In longer stretches of discourse, however, gaze may also function discursively, especially to mark stretches of the conversation in which the narrator’s perspective shifts from that of a narrator to that of a character within the story (Sweetser and Stec 2016). These two functions for gaze could be difficult to coordinate and may be affected by the relationship of the signer and their interlocutor. When conversing with an inattentive interlocutor, a signer might shift the gaze patterns more towards pragmatic–interactive goals like establishing shared attention and comprehension, while sustained and clear attention from an interlocutor could enable a signer to shift their gaze away with confidence that they will not “lose” the focus of their conversation partner in the process.

In this study, we document the coordination of eye gaze and signing in a local sign language from Nebaj, Guatemala in signed narrative accounts of the children’s book Frog Where Are You. We analyze the gaze patterns from two conversations involving adult and child signers from the same extended family. We compare the signers’ gaze patterns as they describe illustrations from the book to their interlocutor, focusing on where they are looking (their gaze target) and how they are signing (what type of signs they produce).

The present study aims to give a broad account of where signers look during conversation and illustrate different factors that guide their use of eye gaze. At the interactional-pragmatic level, we describe how eye gaze is used for interaction—for checking in with a conversational partner or securing their attention. At the discursive–pragmatic level, we ask how signers utilize eye gaze differentially with different kinds of signs, for example, exploring where signers direct their gaze while producing enactment1 and pointing signs versus other signs. To do so, we first analyze the types of signs that appear in the narrative—enactment, deixis (pointing), etc.—and then analyze if patterns in eye gaze vary as a function of sign type. Finally, we ask how the interactional–pragmatic and narrative–discursive levels interact. For example, if signers use eye gaze differently with different sign types, this may restrict (or encourage) the use of eye gaze for pragmatic purposes such as checking in with the interlocutor.

We answer these questions through behavioral coding of naturalistic data and quantitative analysis as well as qualitative analysis of individual examples. The study provides novel insights into how eye gaze operates in some interactions in local sign languages—a communicative circumstance with unique social and cultural characteristics, including the use of the visual/manual modality and heightened ‘precarity’ of mutual understanding—helping to answer questions of universality and specificity of eye gaze patterns in interaction. Our methodological approach to analyzing the two conversations here affords a unique window into the strategies used by signers to balance multiple pressures in interaction. Different levels of interaction make competing demands on eye gaze, and we show that the levels do interact in meaningful ways. This is one of the first studies to quantitatively examine the use of eye gaze simultaneously at multiple levels, with a methodology that can easily be adapted for other sign languages and allows for comparative analysis across languages and contexts.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Eye Gaze and Interaction: Conversation and Narrative

In all conversations (signed or spoken), gaze must be coordinated on at least two dimensions within the interaction. We describe these two functions as pragmatic–interactional and narrative–discursive and ask how they are coordinated and managed by signers of a small local sign language in Guatemala. As discussed in the introduction, the pragmatic–interactional function of gaze characterizes how language users coordinate their gaze with each other and with items in their context. For example, when people look at something in the context together and discuss it, they might shift their gaze to look at that object. Alternatively, when an adult and child engage in “book sharing,” they must coordinate making eye contact with each other by looking at the shared object, in this example, a book. This has been described in the developmental literature as establishing “joint attention” (Moore and Dunham 2014). More broadly, the conversation itself has been described as “joint action” and requires careful calibration of time spent securing your partner’s attention, checking to see whether they have maintained their attention and seem to understand what has just been shared in the conversation, as well as looking at the same targets in the immediate context (Clark 1996; Haviland 2020). This type of gaze coordination is connected to the intersubjective aims of interaction (Edwards 2023; Sidnell 2014) and to managing the flow of conversation, including monitoring for cues about your partner’s attention and comprehension (Levinson 2016, 2020). The pragmatic–interactional function of gaze is shaped by the communicative histories of the people engaged in conversation and factors like their age, familiarity, and hearing status.

The second dimension of gaze coordination, discursive–narrative, describes gaze patterns that are used to mark elements within the discourse. Signed and spoken languages use a blend of semiotic strategies in communication including conventional, deictic, and depictive or enacting strategies (Ferrara and Hodge 2018); different strategies may recruit eye gaze in distinct ways. For example, people will often match their gaze target to the direction of a pointing sign or gesture (deixis) to reinforce the referent. Alternatively, in signed conversations, signers will intentionally gaze at “nothing”—a target that is overtly “empty” of a referent and also involves not making eye contact with their conversation partner(s)—to mark re-enactments of a character within a story (depiction/enactment). Thus signing, like most linguistic exchanges, exhibits “coexpressivity”—it is a multi-modal phenomenon and relies on several channels beyond the manual articulators including facial expressions, body posture, and—the focus of this analysis—eye gaze.

Although these two functions for eye gaze have been discussed and analyzed separately for signed and spoken conversations, they have rarely been considered together (though see Haviland 2020 for one example). In this analysis, we ask whether signers of a local sign language show similar patterns of gaze coordination to those described for other spoken languages and signed languages and we offer a close analysis of how the pragmatic–interactional and discursive–narrative functions of gaze are negotiated by signers within a single conversation.

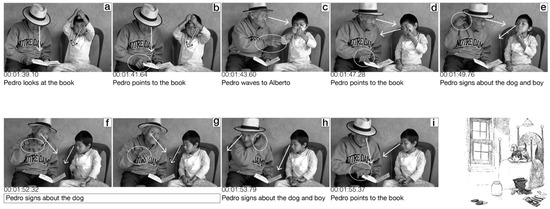

We illustrate these two levels with an example interaction in Figure 1. Pedro, around eighty years old, is seated next to his grandson, Alberto (age 5). On his lap, he holds an illustrated children’s picture book, the page that Pedro describes is shown in the lower right frame of Figure 1. Pedro looks down at the book and points to the characters in the illustration (Figure 1a,b). He looks over to Alberto, who is distracted by a toy, extends his hand to wave at him, and lightly taps his elbow (Figure 1c). Alberto looks down at the book with his grandfather who points to the scene again (Figure 1d). He then returns to his description, depicting how one might happily pet a dog (Figure 1e–h). Finally, Pedro again points to the illustration of the boy and the dog of the bed (Figure 1i).). In the first part (Figure 1a–d), we see how the grandfather checks in on his grandson and ensures his attention. In the second part (Figure 1e–i) he tells the story in the illustration, using a mix of enactments, points to various elements in the description, and other signs. During this second phase, he stops looking to his grandson and his eyes shift elsewhere as he produces the enacting and pointing signs.

Figure 1.

A sequence of signs from the conversation between Pedro and Alberto about the story.

Pedro is deaf, and though his grandson is hearing, Alberto is being raised with two deaf siblings (an older sister and a younger brother) and has frequent conversations with his grandfather using signs. In this interaction, the local sign language they use to communicate is serving multiple functions, including establishing referents and predicating descriptions of events from the story, as well as managing joint action and attention. These different functions make different demands on eye gaze, and Pedro must strike a balance between them. While he initially monitors Alberto to ensure his attention, his gaze is later pulled away from Alberto as he returns to the narration and as he looks to several different locations in a brief period. We now turn to prior studies of eye gaze in conversation and narrative, as well as discursive strategies in narratives across language modalities.

2.1.1. Eye Gaze in Conversation

There is a substantive body of research investigating the relationship between eye gaze and turn-taking in spoken conversation, beginning with Kendon (1967). A recent review paper (Degutyte and Astell 2021) analyzed 29 studies that used both naturalistic data and experimental paradigms to investigate the relationship between eye gaze and several interactional behaviors including starting a turn, ongoing conversation, turn overlaps (simultaneous speech), turn-yielding, the gaze behavior of unaddressed participants, and unwillingness to take a turn (Degutyte and Astell 2021, p. 8). Though the studies varied in their methodologies and datasets, some clear patterns emerged. There was a consistent relationship between eye gaze and turn yielding—people tend to end their turn by looking at the person they anticipate will take up the next turn. Another common finding relates to attention monitoring: the recipient tends to look longer at the person currently producing an utterance. Finally, regarding conversational breakdown and repair, the person initiating a repair often seeks the gaze of their interlocutor (the person with whom they are interacting), sometimes through repetition of the utterance, prior to beginning the repair itself. The relationship between turn initiation and eye gaze is less systematic. Although Kendon’s (1967) original study suggested that language producers tend to look away from their interlocutor when starting a turn; later studies have been mixed in their findings (see Degutyte and Astell 2021, pp. 8–11 and references therein).

Turning to sign language conversations, we find similar patterns. In a study of American Sign Language (ASL), Baker (1977) reports that signers’ gaze patterns at the start of a turn are based on the type of utterance they intend to produce—they will make eye contact with their interlocutor if they are about to ask a question but avert their gaze if they are about to make a statement. Anyone in the conversation not currently signing tended to look at the producer. Further, specific to the visual–manual modality, it has been contested in the literature whether signers require eye contact before initiating a turn (see discussion in Coates and Sutton-Spence 2001). In an analysis of a signed language similar to the communicative interactions that we discuss in this study, Haviland (2020) provides a detailed analysis of eye gaze and turn-taking between three deaf adult signers (and one additional hearing signer in one of the examples) who live in Chiapas, Mexico and use a first-generation sign language referred to as “Z”. As he notes in his description of one conversation, entire turns are initiated and managed with different gaze targets (see pp. 55–65) and gaze alone can be used to establish referents in the discourse in the absence of manual signs. Haviland also introduces the notion of a “gaze to nowhere” (p. 65), which has been discussed elsewhere in the literature as a means for marking major syntactic breaks or a hesitation in signing (Engberg-Pedersen 2015). This “gaze to nowhere” seems to be plurifunctional for signers and speakers, but may be particularly salient in narrative contexts, a point we turn to in the next section.

2.1.2. Eye Gaze in Narrative

In narratives, the producer of the utterance manages multiple viewpoints from within the narrative as well as the interactive or pragmatic constraints and demands of maintaining engagement with their interlocutor(s) (Sweetser and Stec 2016). In his analysis, Haviland distinguishes these two “spaces” using Jakobson’s terminology of narrated events and speech events2 (Jakobson 1957, cited in Haviland 2020). Prior work demonstrates that there are predictable patterns of gaze alternations associated with these competing demands. When storytellers shift into narrated events, their gaze tends to disengage from their interlocutor(s). The conclusion of the narrated event is often marked by a return of their gaze to the storyteller’s interlocutor to check-in (Park 2009; Sidnell 2006; Sweetser and Stec 2016; Thompson and Suzuki 2014). In addition to marking the end of longer narrative stretches, interlocutors tend to “bookend” segments of averted gaze with a concerted effort to establish shared attention with their interlocutor. Producers also seek their interlocutor’s gaze before averting their gaze for a narrated event. Storytellers are aware of the risk of looking away from their conversation partner and establish shared attention through gaze before initiating a lengthy retelling, as Sweetser and Stec note, “joint gaze is sought specifically to enable averted gaze” (p. 248). After they conclude the retelling, they seek to reestablish shared attention through gaze (Thompson and Suzuki 2014; Sweetser and Stec 2016).

Within especially long stretches of spoken narrative, Sweetser and Stec (2016) document a phenomenon termed “visual checking”, in which the narrative producer maintains the narrative role with their hands and body, but quickly checks in visually with their interlocutor. After longer check-ins, speakers might mark the return to their story with an explicit resumptive device like “anyway”—but if these checks are brief enough, they are not marked in the linguistic stream at all (Sweetser and Stec, p. 251). They compare this communicative behavior to backchanneling. Backchanneling can sustain the communication channel in conversation without suggesting a change in turns or ceding of the floor. Examples of backchanneling include nodding and phrases such as ‘uh-huh’ in English. Backchannel phrases have also been documented in sign languages (e.g., Mesch 2016). Visual checking, like backchanneling, does not interrupt the sequence of narrative retelling and permits the narrative producer to sustain the narrative space and character viewpoint.

For the current study, we analyze gaze during longer narrative utterances, and how the two main storytellers (Pedro and Rosa) manage gaze to their interlocutors and gaze to other places in the context, including a “gaze to nowhere”. We explore both the patterns of gaze itself and how gaze is coordinated with different types of signing.

2.2. Enactment in Signed Conversation and Narrative

The study of eye gaze and viewpoint in narrative and discourse is closely tied to the research on enactment. Instead of just telling what the character did, signers (and speakers) can re-enact parts of the story. In enactments, the signer uses their own body to enact the behavior, utterances, or thoughts of another person (Metzger 1995). Researchers who have studied enactment strategies in sign languages have used a wide range of terminology to label enacting phenomena, including constructed action, role shift, and personal transfer, among others (Padden 1986; Metzger 1995; Cuxac and Sallandre 2007). These terms largely—but not perfectly—overlap and the range of terminology reflects the diverse theoretical orientations, motivations, and analyses of researchers working in this area (see Beukeleers and Vermeerbergen 2022 for a review of the field and terminology shifts). For this paper, we use the term enactment.

In an example of enactment from our data, the signer, Rosa, enacts the action and experience of the character (the boy from the story) with her hands but also her facial expression, posture, and eye gaze. This example is illustrated in Section 3.3.2. Enactments are often multi-modal: the face, hands, and body work together to provide a unified construction (Hodge and Ferrara 2014). Enactments also often recruit not just the body but also the space in front and around the signers. The enacted character may be interacting with other referents, and these referents are often ‘located’ in the immediate space of the signer (Liddell 2003; Beukeleers and Vermeerbergen 2022). Additional examples of enactment from our data are provided in Section 4.1 below. These strategies of enactment in sign language have parallels in co-speech gesture (Quinto-Pozos and Parrill 2015; Brentari et al. 2012; Davidson 2015).

Eye gaze shift has been identified as a highly reliable index of enactment strategies (Padden 1986; Herrmann and Steinbach 2012). Cormier et al. (2015) suggest that enactment (‘constructed action’) can be analyzed articulator by articulator: some articulators may participate in the enactment while other articulators do not. The articulators that are not involved in the enactment may be recruited for something entirely different. Signers might produce conventional signs on the hands, describing an event, while also using the face and body to enact the character’s behavior and experience during the event (see ‘subtle CA’ in Cormier et al. 2015).

Enactment is often studied in the context of narrative (e.g., Quinto-Pozos and Parrill 2015 for American Sign Language; Hodge and Ferrara 2014 for Australian Sign Language; Cormier et al. 2013, for British Sign Language). This is because enactment is tightly linked to the narrative genre. In a recent quantitative study of Finnish Sign Language, constructed action comprised 39 percent of the duration of the average story, but only 5 percent in other types of conversation (Puupponen et al. 2022). This finding is echoed by a corpus analysis of Australian Sign Language (Ferrara 2012). Green (2017) observes a similar pattern in her analysis of a signed narrative from Nepal which included more instances of enactment than other communicative practices such as commands or questions. Quinto-Pozos and Mehta (2010) find that the use of enactment in narratives in American Sign Language is common across formal and informal contexts. While enactment strategies are attested across sign languages, their use is also idiosyncratic: research shows high variation across signers in the frequency of enactment, even for the same story (Hodge and Ferrara 2014).

Enactment is often discussed in contrast with other non-enactment strategies, such as conventionalized descriptions. Quinto-Pozos (2007) suggests that constructed action in American Sign Language is sometimes obligatory: certain parts of a story are best told through enactment with no clear ‘conventionalized’ alternatives. In general, however, researchers point to a poetic function of enactment, as it can make the narrative more vivid (Green 2017). Often, enactments appear alongside a description of the same event: in their analysis of Australian Sign Language narratives, Hodge and Ferrara (2014) note that “it was more common for enactment to elaborate the linguistic commentary rather than replace it” (pg. 387).

Eye gaze is often analyzed as having multiple functions in enactments. Most straightforwardly, the signer’s eye gaze may form part of the enactment, showing where the character is looking. However, many researchers have noted that in practice, eye gaze during enactments in sign language often has additional referential or indexical functions. For example, ‘imitative’ eye gaze shifts can also index the (imagined) addressee or recipient of the enacted utterance or action (Engberg-Pedersen 2003). Shifts in eye gaze also help the listener track the beginning and end of enactment—Engberg-Pedersen describes this as a shift between sender-level and character-level (Engberg-Pedersen 2003). Similar to spoken language findings on narrative events, the break and resumption of eye gaze indexes shifts in and out of character (Sweetser and Stec 2016).

We expect a tight link between the use of enactments and the direction of eye gaze in the narratives analyzed. In her work on “natural sign” in Nepal, Green (2017) analyzes how eye gaze, sign type, and perspective in narratives become aligned. For example, eye gaze to the audience was used with conventional signs for the purpose of commentating on the story. To show how the story unfolded from the character’s perspective, however, enactments with averted eye gaze were used. We examine whether we find a similar pattern in the use of eye gaze and enactment in our data.

The spirit of this study follows closely with Beukeleers’s (2020) dissertation work on Flemish Sign Language discourse, which analyzes how eye gaze is used with specific communicative methods (e.g., depiction, including enactment), the functions of eye-gaze in turn taking, and the interplay between the two. Our study examines eye gaze simultaneously on two levels: first, how gaze functions within a narrative with different types of signs (and/or methods of communication), and second, how gaze is used across conversational turns as a tool for managing turn-taking and monitoring the addressee. The different functions of eye gaze could also come into competition, and we are interested in how signers coordinate competing demands on eye gaze.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Fieldsite and Participants

3.1.1. Fieldsite

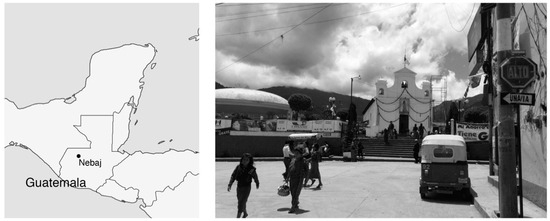

The data for this study were collected in 2015 in Nebaj, a town in the northwest highlands of Guatemala, with a population of 69,162 (INE 2020). The town is the commercial center of the region, but many inhabitants continue to farm milpas, small plots of land outside of town (see Figure 2). Some people also migrate seasonally to the coast of Guatemala or farther north to the United States for paid labor. Most residents of Nebaj are native speakers of Ixil, a Mayan language in the Mam family. Younger residents often also speak Spanish, which is learned in local schools.

Figure 2.

A map showing the location of Nebaj, Guatemala, and an image of the central park and main cathedral in Nebaj.

The first author has conducted fieldwork in Nebaj since 2013, traveling to Guatemala at least once per year for four to six weeks between 2013 and 2019. During that time, she has met nineteen deaf people who live in Nebaj or in nearby aldeas3. According to interviews and conversations with these participants and their family members, Guatemalan Sign Language (LENSEGUA4) was not used in Nebaj during the time period these data were collected. LENSEGUA is reportedly used in larger cities in Guatemala, primarily in Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango (Parks and Parks 2008). For more information on the local sociolinguistic context in Nebaj, see Horton (2018, 2020b).

3.1.2. The Social Context of Local Sign Languages from Nebaj

As noted in the Introduction, there is abundant terminology for the types of sign languages used outside of nationally recognized, institutional contexts (Hou and de Vos 2022). Based on the first author’s informal observations and attempts to identify residents who are deaf, there does not seem to be evidence for a high concentration of deaf people in Nebaj. The author has met or been told about approximately twenty deaf people in the local community, which would equal an incidence of deafness well below the 0.1% rate reported for the United States. Thus, Nebaj does not constitute a “shared signing community” like those reported for Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language or Kata Kolok. We have chosen to use the term “local sign language” because the system that we have observed in this family appears to serve all of the functions of a language and is shared by deaf and hearing members of the family.

Based on conversations with local hearing residents of Nebaj, there is not a legible notion of a communal sign language used by all deaf people in the area. Signers make use of deictic (pointing) forms, familiar locations, and recognizable gestural emblems when they are interacting with hearing people who may be less familiar with their signing. Hearing and deaf residents of Nebaj interact with each other freely in public using improvised gestures and conventional gestural emblems (gestures that have a nameable meaning and are shared and recognized by the speaking community). Patterns of social interactions between deaf and hearing residents of Nebaj are described in detail in Horton (2020a). Though deaf and hearing residents of Nebaj interact informally, this does not mean that signed communication is always fluid and without misunderstanding (Kusters 2010). However, there are instances of informal conversations, for example, a deaf child who works as a shoe-shiner in the local central park helping hearing customers and engaging in extended signed interactions. There are also groups of deaf individuals who interact with each other regularly, including a group of children who attend a local school for special education together, families with multiple deaf relatives like Pedro and Rosa’s family described here, and a group of deaf adult men who work together in the local market transporting goods for vendors from their homes to their stalls. It is difficult to establish the “age” of these local sign languages or the extent of their overlap and conventionalization. The situation seems similar to circumstances that have been described as “familylects” (Sandler et al. 2011) or family sign languages (Hou 2016). Some deaf people seem to engage more with other deaf people, but many are primarily surrounded by hearing friends and relatives.

3.1.3. The Structure of Local Sign Languages from Nebaj

Grammatical patterns, in terms of emergent morphological and phonological structures, have been documented for several individual signers in Nebaj Horton (2018, 2020b) along with patterns of language socialization Horton et al. (2023) and conversational repair Horton (2024). The local sign languages have been analyzed in terms of lexical variation and overlap in Horton (2022). These analyses report a base level of lexical overlap, suggesting some common forms shared across signers in this community, even those who are not in direct contact. For sub-communities with sustained, frequent (daily) interactions, rates of lexical overlap are significantly higher, suggesting a shift towards a more conventionalized, shared lexicon of signs. In terms of grammatical structure, child signers who had input from an adult language sign model showed a morphological pattern documented in many other sign languages in which they use handshape type to mark a contrast in the agentive status of an event. Child signers who were part of a signing community of peers did not show this same pattern (Horton et al. 2018). These local, micro-community sign languages remain relatively under-documented for phonological, morphological, and syntactic structures. This study contributes to the work of understanding how these types of sign languages function in interaction.

3.1.4. Participants

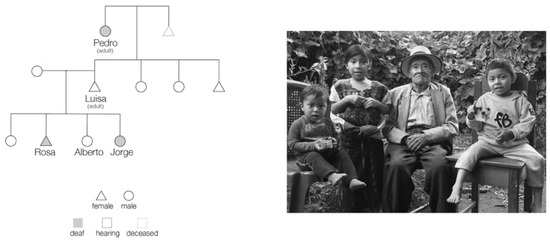

The participants in this analysis include Rosa, age 8, her grandfather, Pedro (age 80), and Rosa’s brother, Alberto (age 5), introduced above (see Figure 3 for a diagram of their family tree). Pedro, as indicated in the opening paragraph, is a deaf man who was around age 80 at the time of this recording. His wife is deceased but was hearing, as are all of his children. His daughter, Luisa, is Rosa and Alberto’s mother and she reports that Pedro had a brother, Ernesto, who also “did not speak” but is now deceased. Based on interviews with hearing family members, Pedro’s brother was his only deaf relative until his grandchildren were born.

Figure 3.

Left: A family tree showing the relationships between Pedro and his grandchildren Rosa and Alberto. Right: an image of Pedro and his grandchildren.

In 2013, the children, Rosa and Alberto, lived together with their nuclear family in a house next to Pedro’s house. Later that year, the family discovered that Jorge, Rosa’s youngest brother (age 3 at the time) was also deaf. By 2015, when the data was collected, Rosa and Alberto’s nuclear family had relocated to a house a short walk away from the original family compound, but the children frequently traveled back and forth between the houses. Luisa reported that the children saw their grandfather (and other relatives in the main house) a few times each week (see Figure 3 for an image of Pedro and his grandchildren).

3.2. Study Procedures and Task

The participants were selected for this analysis because they provided narrative descriptions of this story on several occasions and were afforded an opportunity to conduct a comparative analysis of a deaf adult and deaf child from the same extended family. The first author met this extended family two years earlier, in 2013 when first visiting Nebaj. She was introduced by a mutual friend, Maria, who knew the family and lived down the street. Maria would accompany the author when she visited and provide translation into Ixil as needed. The first author communicated with hearing family members using spoken Spanish and used gestures (initially) to communicate with deaf family members, gradually learning the signs that they use with each other. The author explained to the family that she wanted to learn more about how they communicated with each other, in particular with their children. The study protocol was approved in advance by the University of Chicago IRB5 and all adults indicated their consent to participate and be filmed. At the time these data were collected, the author had visited the family six times, each time staying between one and three hours.

As the first author visited the family, she would bring toys and picture books for the children to play with and look at together or with an adult. One of the picture books was the illustrated children’s book Frog Where Are You (Mayer 1969), a short story about a boy and his dog who lose their pet frog and go searching for it. The story does not have words but consists of a sequence of related illustrations and has been used in a variety of studies of language acquisition (Berman and Slobin 2013). When the first author visited and spent time with Rosa, Pedro, and Alberto, she introduced the book and asked if they would describe it to her or look at it together.

Signers generally kept the book in their lap or on a table in front of them while they provided a narrative description of the scenes on each page (see Figure 1). They referred to characters or scenes by pointing to them as they turned through the pages and also referenced similar or related items in the immediate context or farther away using deictic signs (pointing or indicating signs using the hand, lips, or chin). The length of time to describe the book varied, but it generally took no more than 15–20 min.

3.3. Data and Annotation

3.3.1. Data

This analysis focuses on two narrative retellings of the Frog Where Are You storybook. The first narrative occurred in the summer of 2015 and was primarily an interaction between Rosa and the first author. They were seated in front of the house where she lived with her mother, father, and brothers, down the road from her grandfather. Rosa had seen the book the summer before (2014) and described it then, so she was familiar with the story. She provided extensive descriptions of each page of the book and referred to things in the immediate visual context as well as past events and referents not visibly accessible.

The second narrative, introduced above and in Figure 1, occurred in the winter of 2015. Pedro and Alberto were seated side-by-side with the first just off-screen to the left of Alberto. The author did not participate in this conversation as much as she did in Rosa’s narration. Pedro had seen this book before, the previous year when he looked at it together with Rosa in the summer of 2014.

These two narratives were selected for analysis from a larger set of narratives that the first author has collected from multiple participants longitudinally across multiple years. The narratives analyzed for this study afforded an opportunity to compare two signers who know each other well and are describing the same book. Thus, we expected similar and hopefully comparable referential content. We also felt that these two participants offered interesting contrasts, based on the characteristics of the conversational partners for each narrative. In the first case, the first author was familiar to Rosa, but also visibly an outsider to this community and not a native user of this sign language. In the second case, Alberto is a hearing child signer who interacts with his grandfather regularly, but also exhibits predictable patterns of engagement and distraction while looking at the book together with his grandfather.

3.3.2. Annotation

All videos were annotated and coded in Elan, a time-synced linguistic annotation software (ELAN 2023, version 6.8). Sign glosses and sign type were annotated by the first author who was present for both elicitation sessions. The first author is familiar with the signs that Pedro and Rosa use based on repeated interactions with them across several years of fieldsite visits. The second author completed the gaze target coding (described below). This author has previously coded eye gaze direction in users of American Sign Language (ASL) (Waller 2021) and is a fluent user of ASL. Both authors met and discussed any codes that were ambiguous or difficult to assess. Disagreements were resolved through these discussions and noted in the coding manual. The intercoder agreement was calculated for the gaze target and was 95%.

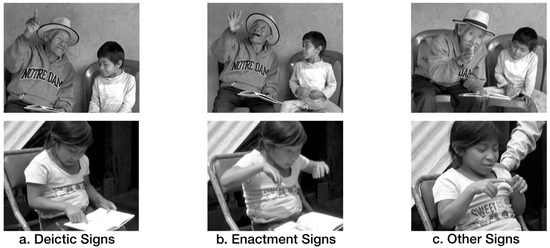

Signs were glossed and coded for their sign type. These types included: deictic signs, enactments, other signs, pragmatic signs, and signs that were unclear (their type could not be determined). Deictic signs consisted of pointing forms. In this community, deictic signs and gestures can be produced with the hands, lips, or chin with or without movement (see Figure 4a for examples from this dataset). In these narratives, signers used exclusively manual points, though we monitored for non-manual points. For deictic signs, we also coded the target of the point. Enactment signs were coded when the signer represented a character or events from the story using facial, bodily or manual enactments that imitated or resembled the current illustration, or a preceding illustration (see Figure 4b for examples). Other signs included conventional signs that Rosa and Pedro use that resemble common gestural emblems from the community (see Le Guen et al. 2020 and Safar 2019 for similar examples and discussion from Yucatec Mayan Sign Language), as well as signs that iconically represent a shape dimension of the referent or how the referent might be handled, similar to classifier signs (see Figure 4c for examples). Pragmatic signs were produced to direct, redirect, or attract an interlocutor’s attention, see Figure 1c for an example of Pedro getting Alberto’s attention.

Figure 4.

Examples of each sign type from the narratives, with (a) deictic (pointing signs) to the book and other locations, (b) enactment signs imitating characters and events, and (c) other types of signs including classifiers and conventional forms.

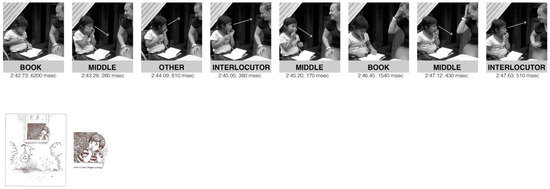

In addition to glossing and coding the manual and non-manual signs produced in the narratives, we continuously coded the direction of their eye gaze. Eye gaze targets included: the book, an interlocutor, a “middle” space, other, and unknown/ambiguous. For Interlocutor, we also coded where the signer’s attention was directed (which interlocutor). The Middle space was coded when the participant looked forward “between” their interlocutor and the camera, and did not look at their hands, an interlocutor, or another marked location. Other was coded as the target when the signer looked elsewhere, meaning they were not directing their gaze at the book, their interlocutor, or the middle space. Other gaze targets included present items, imagined or non-visible locations, and the signer’s own hands. This code also was used when signers closed their eyes. Lastly, the gaze target was coded as Unknown/Ambiguous if it was not possible to determine the target based on the camera angle. Examples of each gaze target are provided in Figure 5. During this sequence, Rosa produced six signs that co-occurred with nine gaze targets. Two times in the sequence she checked in with the interlocutor (at 2:45.05 and 2:47.63).

Figure 5.

Examples of gaze target, coded in a 6 s sequence of signs from Rosa’s narrative (02:42.5—02:48.0). In the second through the fourth image, as well as the seventh, she is producing an enacting sign representing the boy from the illustration below. She first replicates his gaze target, looking to her left, but also looks ahead to the middle space, while maintaining her pose with her finger to her lips.

4. Results

In the following sections, we provide analyses of the narrative data. First, we discuss what kinds of signs were used in each of the narratives. The results of this analysis are presented in Section 4.1. Then, we ask where signers look during the conversation. This analysis appears in Section 4.2. Lastly, we ask how signers coordinated their eye gaze and signing. This is the analysis described in Section 4.3.

4.1. Sign Type: How Are Signers Telling Narratives?

Rosa and Pedro’s narratives were coded for the types of signs they used throughout their conversations. They had different rates and styles of signing. During her interaction, Rosa produced 582 signs, an average rate of 52 signs per minute while Pedro produced 150 signs for an average rate of 37.5 signs per minute6. All signs were coded as Deictic (pointing), Enactment, Pragmatic (waves, taps for attention), Other (conventional signs, classifier signs), or Unclear (category could not be determined). See Section 3.3 and Figure 4 and Figure 5 for a more detailed description of sign types with examples. Table 1 shows the distribution of sign types for both signers.

Table 1.

Proportion of Sign Types for Pedro and Rosa’s Narratives. Proportion (N signs).

For both signers, Deictic or pointing signs comprised around half of their productions (51% of Pedro’s signs and 57% of Rosa’s signs). Signers pointed to different parts of the illustrations in the story, but they also pointed to places and objects in the visible context (i.e., in the yard in front of them) and in the distance (referring to known or unknown places that were not visible to the people engaged in the conversation). In one instance, Pedro pointed to an imagined referential location established in prior discourse, pointing up to refer to the location of a beehive on a tree branch represented in the story (see Figure 4a). The next most frequent sign type for both signers was the category of Other, which primarily consists of conventional signs that resemble gestural emblems used in the community and classifier-type signs for objects or animals. For Pedro, Other signs were quite frequent, comprising about one-third of his utterances (37%) while only a quarter of Rosa’s signs were of this type (25%). It was more common for Pedro to use conventional signs (coded as Other), like the one for CHILD, when referring to the boy in the story, for example, while Rosa was more likely to use enacting signs to depict the boy’s pose or behavior in the illustration (examples of these signs are discussed in Section 4.1). Rosa used significantly more Enactment signs (18%) than Pedro (7%) to depict events from the story. Lastly, Pedro used Pragmatic signs—manual signs like waves or taps to redirect his grandson Alberto’s attention (5% of all signs, see Figure 1c for an example) while Rosa never directed signs like this to her primary interlocutor. We provide two detailed examples that illustrate these patterns in Rosa and Pedro’s signing.

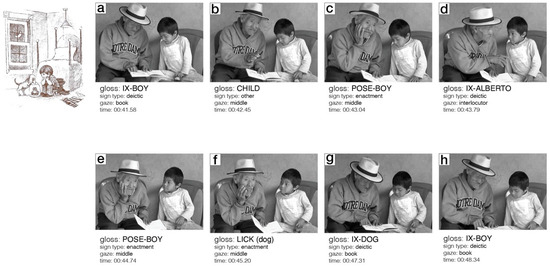

In the distribution of signing strategies, Pedro and Rosa look similar in their frequent use of indexical, pointing, strategies, but diverge in their rates of enacting versus other types of signs. The following two examples illustrate some of the similarities and differences between their narratives. In Figure 6 and Figure 7, Pedro and Rosa describe one of the early pages of the book, with an illustration of the boy and dog looking at their pet frog in a jar on the floor of their bedroom. For each frame, we provide the gloss of the sign, the sign type, the gaze target, and the timestamp. These segments are not the entire description of this page, but capture some of the shifts in eye gaze, as well as sequences of signs that were used in their narratives.

Figure 6.

Part of Rosa’s description of an early scene with the boy, dog, and frog. In this segment, she produces four signs, including two signs in which she enacts the pose of the boy, one deictic sign to the book, and one sign that is conventionally used to mean “sit” in this community. In (a), Rosa recreates the boy’s pose from the illustration (far left image). In (b), Rosa points to the boy in the illustration. In (c), Rosa signs SIT. In (d), Rosa repeats the enacting sign showing the boy’s pose with his chin resting in his hands.

Figure 7.

Part of Pedro’s description of an early scene with the boy, dog, and frog. In this segment, he produces eight signs, including two signs in which he enacts the pose of the boy, one sign in which he represents the dog “licking” with his tongue, three deictic signs to the book, one deictic sign to Alberto, and one sign that is conventionally used to mean “child” in this community. In (a), Pedro points to the boy in the illustration from the book (shown in the far left picture). In (b), Pedro produces a sign for CHILD, which resembles a local gestural emblem. In (c), Pedro enacts the boy’s pose from the illustration, resting his chin on his hand. In (d), Pedro points to Alberto. In (e), Pedro repeats the enacting sign showing the boy’s pose. In (f), Pedro holds his hand in the position of the enacting pose, but represents the dog showing a licking movement with his mouth. In (g), Pedro points to the dog in the illustration. In (h), Pedro again points to the boy in the illustration.

The two sample utterances in Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate several key features of Rosa and Pedro’s narratives. First, they both anchor enactment signs (in Figure 6a,d and Figure 7c,e,f) with deictic signs, pointing to the character they are representing in the illustration (in Figure 6b and Figure 7a,g,h). To refer to the boy in the illustration, Pedro starts by pointing to the illustration (Figure 7a), then provides a conventional sign for CHILD (Figure 7b), then produces an enactment representing the pose of the boy with his hand on his face (Figure 7c). Pedro then points to his grandson (Figure 7d) and repeats the enacting sign representing the boy (Figure 7e) followed by an enacting sign representing the dog in the scene (Figure 7f). Pedro concludes by pointing to each character in the illustration (Figure 7g,h). While Pedro bookends his description with deictic signs to the book, Rosa first produces an enacting sign representing the boy (Figure 6a), followed by a deictic sign to the boy in the illustration (Figure 6b) and a conventional sign that means SIT (Figure 6c). She concludes by repeating the enacting sign for the boy (Figure 6d). Rosa and Pedro’s gaze patterns in these sequences illustrate our findings as well, discussed further in Section 4.2 below—they both look at the book when pointing to it and look to the middle space when producing enactment signs.

While Rosa uses two strategies to refer to the boy—both enactment and deictic signs to the book—Pedro deploys four different efforts to reference the same character for Alberto. Like Rosa, he uses enactment and deictic signs to the book, but he includes a conventional sign that many signers and hearing people use to refer to children in this community. This form is produced with a flat hand extended in front of the signer’s torso, with the palm down to the ground, roughly indicating the height of a child (see Le Guen et al. 2020; Horton 2020c for examples and discussion of these forms across the region). Pedro also points to Alberto in this sequence, we interpreted this to be an extension of the meaning of child/boy to Alberto, something like “Look, there is a boy in this story, like you, he’s sitting like this.” While Pedro and Rosa both use a combination of enactment and deictic signs here, Pedro invokes more diverse referential strategies.

4.2. Gaze in Interaction: Where Are Signers Looking?

4.2.1. Rate of Eye Gaze Shifts

Rosa and Pedro’s narratives were coded continuously for the direction of eye gaze (see Table 1 for a summary). In Rosa’s narrative, we identified a total of 428 shifts in the direction of eye gaze. Gaze shifts occurred every 1.8 s on average. We identified 145 shifts in Pedro’s narrative, these occurred on average every 3.2 s.

For each signer, the total time spent signing and the number of gaze shifts are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Total time signing versus not signing and total gaze shifts.

Both signers did not sign continuously for the entire activity, particularly Pedro. Signers often paused to read the picture book, or while an interlocutor signed or engaged in another activity. Altogether, Rosa signed during 85% (11:02) of the activity, the remainder being non-signing activity7; Pedro signed for only 54% (4:07) of the total time (Table 1).

In Table 3, we compare the rate of gaze shifts (measured in mean number of seconds between eye gaze shifts) when signing versus not signing for each participant. Both signers shifted their gaze less often when not signing—particularly Pedro. When he was not signing, the average duration between Pedro’s gaze shifts was 8.3 s, three times longer than Rosa at 2.7 s. But while signing, the two signers converged in their rate of eye gaze shifts, averaging 1.7–1.8 s between shifts.

Table 3.

Rate of eye gaze shifts while signing vs. not signing (seconds/shift).

The overall median length of time of each eye gaze ‘look’ (eye gaze directed to one location without any shifts) was even shorter than the mean suggests: the median time for a look was 0.8 s for Rosa and 1.1 s for Pedro—for both signers, the majority of ‘looks’ lasted around one second or less—with a few extended looks lasting 10 s or longer.

4.2.2. Distribution of Eye Gaze Target

If we look at where they directed their eye gaze, we see that the signers most often looked at the book, whether signing or not. We present the total distribution of gaze targets while Pedro and Rosa were signing in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distribution of eye gaze (by duration) while signing.

In non-signing stretches, Pedro tended to look at the book, presumably to see what was coming next in the story. Pedro looked at the book 90% of the time that he was not signing. During stretches when she was not signing, Rosa looked at the book 59% of the time. In a few instances of non-signing, she was instead distracted by other interactions happening around her. While signing, Pedro and Rosa generally directed their gaze to the book, at similar rates: Pedro looked at the book 68% of the time and Rosa looked at the book 71% of the time. In fact, their overall distribution of gaze patterns while signing is remarkably similar across all categories (see Table 4). After the book, the most frequent gaze targets were the (primary) interlocutor (for Rosa, this was the first author; for Pedro, this was his grandson) and the middle area between their interlocutor and the camera—accounting for 10–12% of the looking time each. Other locations and interlocutors account for 5–6% of the looking time.

One reason that looking time at the book is much longer than others is that individual looks at the book are much longer than looks to other targets. For Rosa, the median length for gazes directed to the book was 2.6 s (while signing). In contrast, the median length of looks to the “Middle” area was only 0.64 s. Median looks to her interlocutor lasted 0.54, four to five times shorter than the duration of her looks at the book. For Pedro, looks to the book had a median time of 1.9 s, while looks to the middle area averaged 0.8 s, and looks to his interlocutor averaged 0.6 s.

Overall, gaze patterns while signing are characterized by relatively long looks to the book, interspersed with many brief looks to other locations. Often the gazes away from the book happen in sequence: a signer may engage in an extended look at the book but when they look away from the book, they will shift their gaze between 2–3 targets before returning to the book for another extended look. This gives an uneven rhythm to the eye gaze shifts; long gazes to the book are interrupted by a burst of eye gaze shifts elsewhere.

One gaze target location we will return to in later sections is the “Middle”. This target stands out because it appears to be exclusively used in signing contexts. As nothing is actually present between the camera and interlocutors, the narrators very rarely looked at that space when they were not signing (less than 2% of the time). This pattern suggests that gaze to the “Middle” space is only recruited for the purposes of narration.

4.3. Gaze and Sign Type: How Are Sign Type and Gaze Integrated in Interaction?

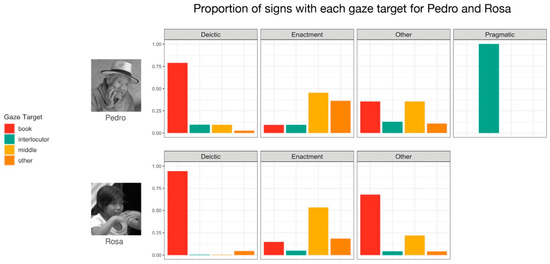

In the preceding sections, we discussed the gaze and signing patterns for Pedro and Rosa separately, but these behaviors were co-occurring throughout their conversations. We now turn to the relationship between gaze and sign type, asking whether some sign types were more likely to be produced with specific gaze targets. For this analysis, we use the main gaze target for each sign. For most signs, the signer did not shift their gaze during the course of the sign, but if they did, we prioritized the eye gaze direction while the signer moved their hands (i.e., discounting eye gaze during the final hold). If signers shifted their eyes while moving their hands, we categorized main eye gaze as unknown/ambiguous and excluded them (n = 17). Figure 8 shows the proportion of signs with each gaze target (book, interlocutor, middle, or other) for each sign type (deictic, enactment, other, or pragmatic).

Figure 8.

The proportion of signs with each gaze target (book, interlocutor, middle, or other) for each sign type (deictic, enactment, other, or pragmatic) for Pedro (top row) and Rosa (bottom row).

Beginning with deictic (pointing) signs (leftmost charts in Figure 6), the most common sign type for both signers (see Section 4.2), we can see that both Pedro and Rosa predominately looked at the book while producing pointing signs. The majority of these points were directed at the book—92% of Rosa’s deictic signs and 79% of Pedro’s deictic signs—thus it makes sense that signers looked to where they were pointing and that their attention was directed to the book while producing these signs.

Signers had a markedly different pattern of looking when they were producing enacting signs in which they represented a character from the story with some combination of their body, face, and hands. For these signs, both Rosa and Pedro most commonly looked to the “middle” space, between the camera and their interlocutor. As discussed above, this gaze direction has been noted by other signers and speakers as a marker of narrated events and adopting the perspective of a character (Haviland 2020; Green 2017; Sweetser and Stec 2016). When signers looked to the middle space, it was clear that they were intentionally not looking at the book, a co-present object, or their interlocutor. The other primary gaze target for enactment signs was “other,” a substantial percentage of these signs included instances when the signer did not look to the middle space, but instead replicated the gaze direction of the character they were describing from the story. For example, if the boy was balanced on a windowsill, looking to his left side, Rosa might turn her head to the left while recreating the boy’s pose (see Figure 5) or if the dog was jumping on a tree and looking up, the signer might direct their gaze up while imitating the behavior of the dog with their body and hands (see Figure 4b).

Pedro and Rosa’s looking patterns differed for the final category of signs, coded as “Other”. As described in Section 3.3, this included conventional signs based on gestural emblems as well as signs that could be considered classifiers that represented objects or animals from the story. Rosa tended to look at the book while producing these signs (over 70% of these signs were produced while she looked at the book), while Pedro tended to be looking at either the book or to the middle space for these signs. It is possible that there is a stronger relationship between gaze target and sign type for Rosa, who primarily reserves the middle space for enactment signs. This could contrast with Pedro, who seems to look to the middle space for both enacting and other types of signs. We plan to explore this pattern of results further in a future analysis. Lastly, only Pedro used pragmatic signs, intended to redirect the attention of his grandson’s interlocutor and he was always looking at Alberto when he produced these waves and taps.

4.4. Gaze Sequence and Signing Rhythm: Signer Check-ins

In the previous sections we observed that while signing, Rosa and Pedro looked at their interlocutor approximately 12% of the time. More specifically, 15% of Pedro’s signs (22 signs) are produced while looking at his grandson—in seven of these signs, he is explicitly calling for his grandson’s attention. When signs are categorized by their “primary” gaze target, these rates are even lower. For Rosa, who does not use any attention-getting signs, only 2% of her signs (12 signs) are produced looking at the researcher. Nonetheless, both signers frequently looked at their interlocutors while signing—often to ‘check-in’ to make sure their conversational partner understood them, to check if they had something to contribute or to ensure they were paying attention. Over the course of signing the story, Rosa looks at her interlocutor 135 times—a rate of once every 4.9 s (or once every 4 signs). Pedro looks at his interlocutor once every 7.7 s, closer to once every 5 signs (34 check-ins total). Many of these check-ins are brief (the median length is 0.5 s for Rosa and 0.7 for Pedro) and ‘between signs’; check-ins often happen as one sign finishes and before the next sign begins. Overall, 28% of Rosa’s signs are followed by a check-in (plus the 2% produced during a check-in), and 17% of Pedro’s signs are followed by a check-in (while another 15% are produced alongside a check-in, as in attention-getting signs).

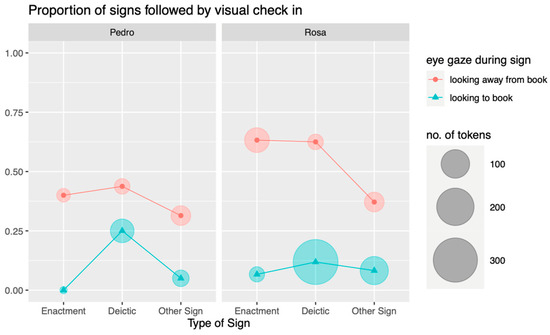

These findings suggest that Rosa and Pedro are aware of the pragmatic demands of breaking off eye gaze from their interlocutors (whether for deictic or discursive purposes) and recognize the risks of losing the attention or comprehension of their interlocutors. We further analyze our data to see what triggers the signers’ ‘check-ins’. As these check-ins often occur during brief pauses or as signers finish a sign, we investigate whether we can predict the occurrence of a check-in based on the properties of the signed word immediately preceding it. Figure 9 examines the role of two factors in whether the signer chooses to ‘check-in’: (1) where they were looking during the sign, and (2) the type of sign.

Figure 9.

The proportion of Rosa and Pedro’s signs that were followed by a visual check-in with an interlocutor.

For eye gaze, we compare two categories: looking at the book during the sign or looking elsewhere during the sign. Figure 9 shows both signers engaged in relatively few visual check-ins after signs in which their eye gaze was directed at the book (lower blue lines, triangles). 20% of Pedro’s and 11% of Rosa’s signs with a gaze to the book were followed by check-ins. When looking elsewhere (not at the book, for example at the middle area or off-screen) both signers were more likely to check-in. For Rosa, the rate of check-ins increases to 55%, while for Pedro the check-in rate increases to 36%.

For sign type, we focus on three categories: enactments, deictic signs, and other signs. Pragmatic signs, which were only produced by Pedro and always involved looking at the interlocutor, are excluded. Rosa checks in after 62% of enactments, 33% of deictic signs, and 25% of other signs. Pedro checks in after 36% of enactments, 29% of deictic signs, and 22% of other signs. The differences between sign types may, however, be driven by eye gaze during sign: most deictic signs are produced looking at the book. As Figure 9 shows, once signs are categorized by eye gaze direction, the effect of sign type is relatively weak in comparison—although we see ‘other signs’ generally trigger fewer check-ins than deictics once eye gaze and signer are controlled for.

Both Rosa and Pedro frequently check-in during their signing, especially Rosa. However, for Rosa, the check-ins tended to happen immediately after signs. For Pedro, check-ins tended to happen after or during the sign. Altogether, about 30% of Rosa’s signs are followed by a check-in or co-occur with a check-in compared to 31% of Pedro’s signs. The choice to check-in with their interlocutor is driven mostly by the direction of their eye gaze during the preceding sign: signs produced with a gaze directed at the book tend not to trigger check-ins, while gaze directed elsewhere (including middle area, or other locations off to the side or upward) are more likely to trigger check-ins—especially for Rosa.

5. Discussion

5.1. Narratives in a Local Sign Language

Though Pedro is an adult and Rosa is a child, many of their gaze and signing patterns are quite similar. It is clear from the analyses above that both Pedro and Rosa are monitoring the attention of their interlocutor as they sign about the book in front of them. In this section, we review some overall patterns that emerge across both narratives and also some differences between the two narratives based on our quantitative findings and our qualitative impressions from being present during the interactions and subsequent analysis of the videos.

5.1.1. Overall Pattens of Eye Gaze and Sign Type in the Narratives

One of the original goals of the paper was to document general patterns of eye gaze and sign types in the narratives. We report some clear overall patterns that hold across both narratives with respect to eye gaze, sign type, and the interplay between the two.

In terms of their signing strategies for producing the narratives, Rosa and Pedro relied extensively on deictic forms to refer to characters and events from the story: deictic signs made up just over half of all signs in both narratives. They pointed to different elements of the illustrations as they turned the pages of the book, and often initiated a descriptive sequence by pointing to an event or character before producing an enactment or other type of signed description. These high rates of deictic signs would be expected during a book-sharing activity. The illustrations offer a natural way to ground the referential content of utterances and it is logical for signers to establish who or what they will talk about by first pointing to it in the illustration in front of them. They also both used enacting signs to describe and/or refer to characters, particularly Rosa. Finally, both (but especially Pedro) used other signs that were neither enacting nor deictic. However, outside of deictic signs, the two narratives differ in how frequently they utilize different sign types. Rosa used more enactment compared to Pedro, and almost no pragmatic or attention-getting signs.

Rosa and Pedro had similar gaze patterns while signing—they divided their eye gaze between several targets including the book, interlocutor, and the middle space; the overall distribution of their looking time was very similar. Both signers shifted their gaze frequently, with a mean of once every 1.8 s (median at 0.8–1.1 s) across the two narratives. But, as noted near the end of Section 4.1, signers’ gaze shifts were regularly timed; rather, lengthy looks to a single target (usually to the book, looking at illustrations) would be followed by short bursts of frequent gaze shifts—especially while signing. Throughout their conversations, the signers spent the majority of the time looking at the book, followed by gaze to their interlocutor and to the “middle space” between the interlocutor and camera. The proportion of gaze targets is remarkably similar for both signers, suggesting that there is reasonable similarity in the type of interaction in which they were engaged, though we highlight some differences in the next section. They also regularly check-in with their interlocutor, about once every 4 to 5 signs—although, like eye gaze shifts, check-ins are not distributed evenly across the narratives.

When we consider coexpressivity and how eye gaze target and sign type interact, Pedro and Rosa again look very similar in their narratives. Both signers most often combined deictic signs (typically pointing to the book) with gaze to the book and enacting signs with gaze to the middle space. They also were more likely to visually check-in with their primary interlocutor following enacting and deictic signs, especially if they were looking at a location other than the book while signing. Pedro and Rosa were far less likely to engage in a visual check-in after looking at the book, potentially because they felt more confident that their interlocutor was jointly engaged in the task of looking at the book.

Both signers utilize a variety of eye gaze targets and sign types and shift between different sign types and eye gaze targets throughout the narrative. Moreover, eye gaze and sign type are linked together: for example, both tend to use the ’middle space’ for enacting signs. Both signers also visually check-in with their interlocutor frequently approximately every four to five signs. The choice to check-in is motivated by two factors: what they were signing just before and where they were looking during that sign. Despite these overall patterns, the narratives also diverge in several respects related to sign types and looking patterns, which we turn to now.

5.1.2. Differences in the Narratives

The first significant difference between these two interactions concerns the interlocutor (conversation partner). Rosa was signing to the first author, who maintained her attention on Rosa throughout their exchange. Each time that Rosa looked to her left to visually check-in with her interlocutor, the researcher provided supportive nods, smiles, and points to the book, making it clear that she was jointly engaged with the book and attentive to Rosa’s narration. On the other hand, the researcher was an obvious outsider to this community and not a native signer of Rosa and Pedro’s local sign language. Thus, it is possible that Rosa felt inclined to provide additional elaboration or explanation in her narrative. In contrast to the researcher’s overtly attentive recipient style, Alberto, Pedro’s hearing grandson, was frequently inattentive as his grandfather described the book. Alberto was holding a toy and often looked around at the yard in front of him or to the researcher seated to his left. Pedro recognized his grandson’s wandering gaze and often checked to see where he was looking before starting to sign. As noted above, Pedro also engaged in explicit manual signs to redirect Alberto’s attention. Pedro used both waves and taps (see Figure 1c), similar to the form described for “Z” sign language (Haviland 2015, 2022) and commonly used in many national sign languages to get the attention of fellow signers prior to starting a turn. These prompting signs were necessary to attract Alberto’s attention and Pedro repeatedly worked to establish joint attention on the book and the narrative task between himself and his grandson.

An additional difference between Rosa and Pedro concerns their early signing experience. Though Rosa is growing up with a deaf–signing grandfather and a hearing mother who has signed with her father since she was born, Pedro’s childhood experiences are harder to document. According to reports from family, he had a deaf, signing communication partner in his brother, Ernesto, but we do not know if he had any adult signing models or how his other hearing family members communicated with him as he was growing up. Currently, Pedro interacts with neighbors and other hearing adults regularly, so while Rosa has both adult and peer signing partners, she has less experience interacting with a variety of hearing communication partners outside her home context. This will change as she gets older and attends school regularly.

5.2. The Discursive–Narrative Function of Eye Gaze

As noted in the introduction, eye gaze is plurifunctional for signers and speakers alike. In the narratives we have discussed, we find that gaze operates at (minimally) two levels: the discursive–narrative and the pragmatic–interactional. The discursive–narrative function of gaze refers to the use of gaze by signers to mark certain types of discourse, specifically narrative, while the pragmatic–interactional function refers to the use of gaze to manage joint attention and monitor for understanding. We begin with a discussion of the discursive–narrative function.

We were curious whether Rosa and Pedro, who use a local multi-generational sign language, would coordinate their eye gaze and signing in patterns similar to those reported for signers and speakers of other languages as they tell stories. One hypothesis is that Rosa and Pedro would be less likely to use a gaze pattern that might risk confusion or losing the attention of their interlocutor. As Horton (2020a) has discussed for this community and others have observed, signers in many communities like Nebaj often encounter communication partners who have variable degrees of proficiency with signing and manual–visual communication (Horton et al. 2023; Goico 2019, 2024; Graif 2018; Green 2014; Hou 2020; Kusters 2017; Reed 2022; Safar 2019). As noted in the introduction, it is possible, given the precarity of their typical social exchanges that signers would adjust to sustain the attention of their interlocutor. However, we find that Rosa and Pedro do use a “gaze to nowhere” or the “middle space,” and they use it exclusively while signing. Rosa almost always combined an enactment sign with gaze to the middle space (see Figure 6a, 6d for examples), while Pedro combined both enactment signs (see Figure 7c,e,f) and other signs (see Figure 7b) with gaze to “middle”.

In terms of its mapping to the gaze of the character in the enactment, the middle space can have a veridical or non-veridical mapping, and this is why we also frequently found signers looking to “other” gaze targets while producing enactment signs (see Figure 4b and Figure 5). If a character is looking to their left side, for example, a signer must choose to either produce a veridical representation of that posture (and look to their left side) or a non-veridical representation of the pose with a gaze to the middle space (their front) that sustains the narrative encoding of the sign. The signer must gauge whether their interlocutor will still correctly interpret their utterance, absent the veridical mapping of the pose of the character to their body. Rosa and Pedro seemed to vary in this decision, sometimes choosing to look to their side or up, to veridically recreate the pose of a character, but also choosing to look to the front sometimes, even when the character’s gaze was elsewhere.

The middle space is also significant as a marker of enactment because this space is “unoccupied”. Gaze to the space between their interlocutor and the camera, as Haviland (2020) noted in his analysis of “Z” is tied to narrative events instead of utterance (speech) events partly because it lacks any referent (person or objects) in the physical context that could be referred to in the utterance event. In this sense, the gaze to the middle space is markedly not “interactive” and can only be interpreted if the interlocutor maps the abstract narrative space onto the gaze target with the signer. It is striking that Rosa and Pedro employ this gaze pattern in ways that closely resemble patterns reported for narrated speech events (Sweetser and Stec 2016) and signed narratives (Engberg-Pedersen 2003; Green 2017).

One crucial difference with respect to previous literature: most literature explicitly or implicitly assumes that eye gaze shifts during enactments involve breaking eye contact with the interlocutor. However, in the narratives analyzed here, signers are most often looking at the book, not their interlocutor. When shifting into enactment, we frequently see signers shifting eye gaze directly from the book to the middle area—it is the shift to the middle area that marks the start of the enactment, not a break in eye gaze from the interlocutor.

5.3. The Pragmatic–Interactional Function of Eye Gaze

In addition to functioning as a marker of narrative events or narrative space, gaze coordination is an essential component of the pragmatic–interactional aspect of conversation. For languages in the visual–manual modality, visual monitoring and attention are necessary for signers to comprehend and follow their interlocutor’s utterance. A signer must orchestrate the referential and discursive functions of their gaze while also checking to be sure that their interlocutor is still attending to their signing and maintaining a shared perspective. This gaze-following is not automatic, and young deaf children exposed to sign languages appear to develop the ability earlier than hearing–speaking children (Brooks et al. 2020). There is also a protracted time course for the development of appropriate gaze following in signed conversations for deaf children acquiring sign languages in a classroom setting (Horton and Singleton 2022).

The task of gaze and attention monitoring is shaped by the communicative context and the presence of other possible interlocutors and objects. In our data, the presence of the book structured the communicative task and provided a shared common ground for the interaction. The book also functioned as a communicative tool for the signers to establish reference, as they did with frequent deictic signs discussed above. Rosa and Pedro were able to take for granted that their interlocutor was equally engaged in the task of looking at the book together, thus gaze to the book was a relatively low-risk gaze behavior (this was not always the case for Alberto, who, as mentioned above, was sometimes prompted by Pedro to look at specific parts of the illustrations or to redirect his attention to the book). The low-risk nature of gaze to the book is reflected in the finding discussed in Section 4.4—signers were far less likely to visually check-in with their interlocutor after looking at the book compared to other locations.

The use of check-ins is consistent with Sweetser and Stec’s (2016) claim that narrators often seek eye contact after shifting eye gaze (though we suggest the initial break in eye gaze is less important). However, this behavior is not just restricted to seeking eye gaze contact after character enactment. When Rosa points to and looks at, a nearby house for the first time—comparing it to a house in the story—she uses the same pattern of check-in after looking over to the house. Shifts in eye gaze to referents that are present and visible to the signers can also trigger a check-in if the referent has not yet been mentioned in the discourse.