Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]isimas gracias: A Sociophonetic Study of the Alveolar Affricate in Peninsular Spanish Political Speech

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Identity, Political Speech, and the Spanish Affricate

2.1. Sociophonetics and Political Speech

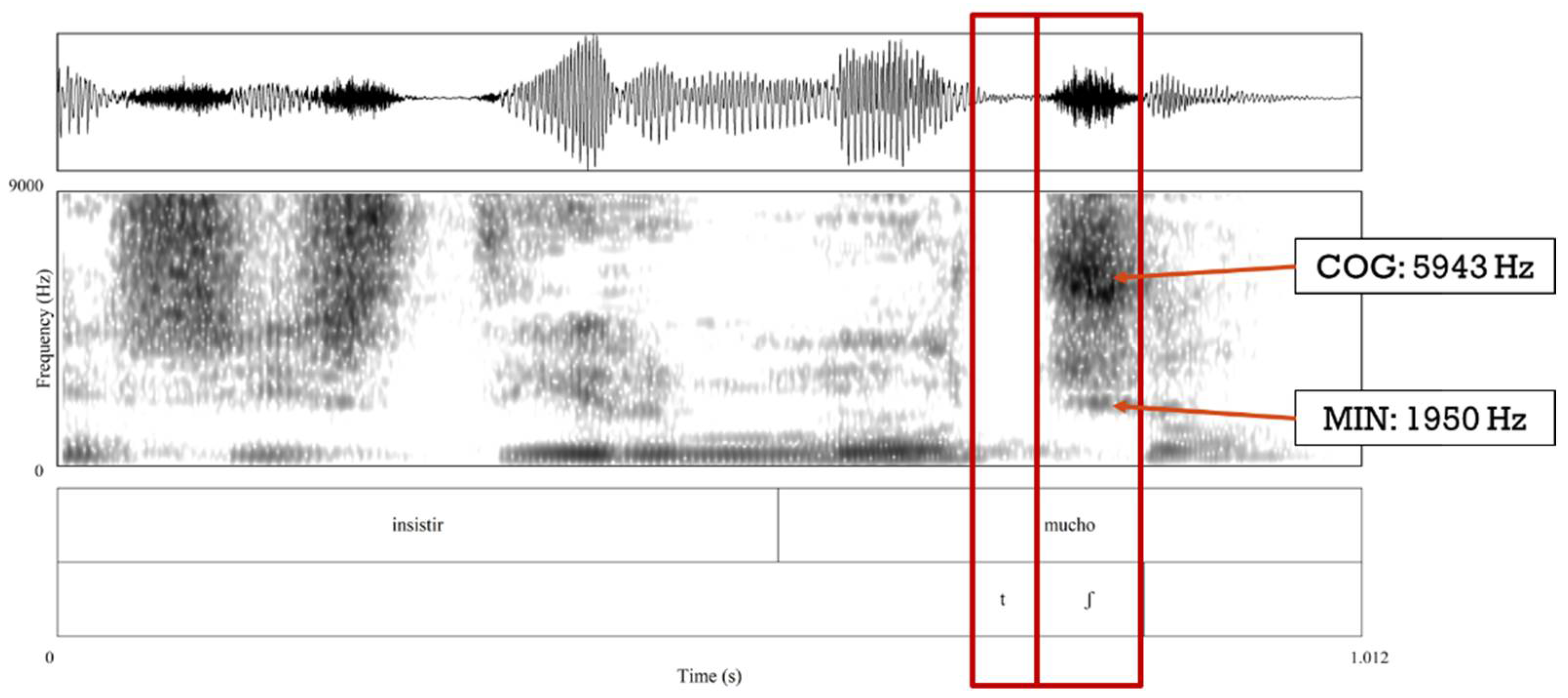

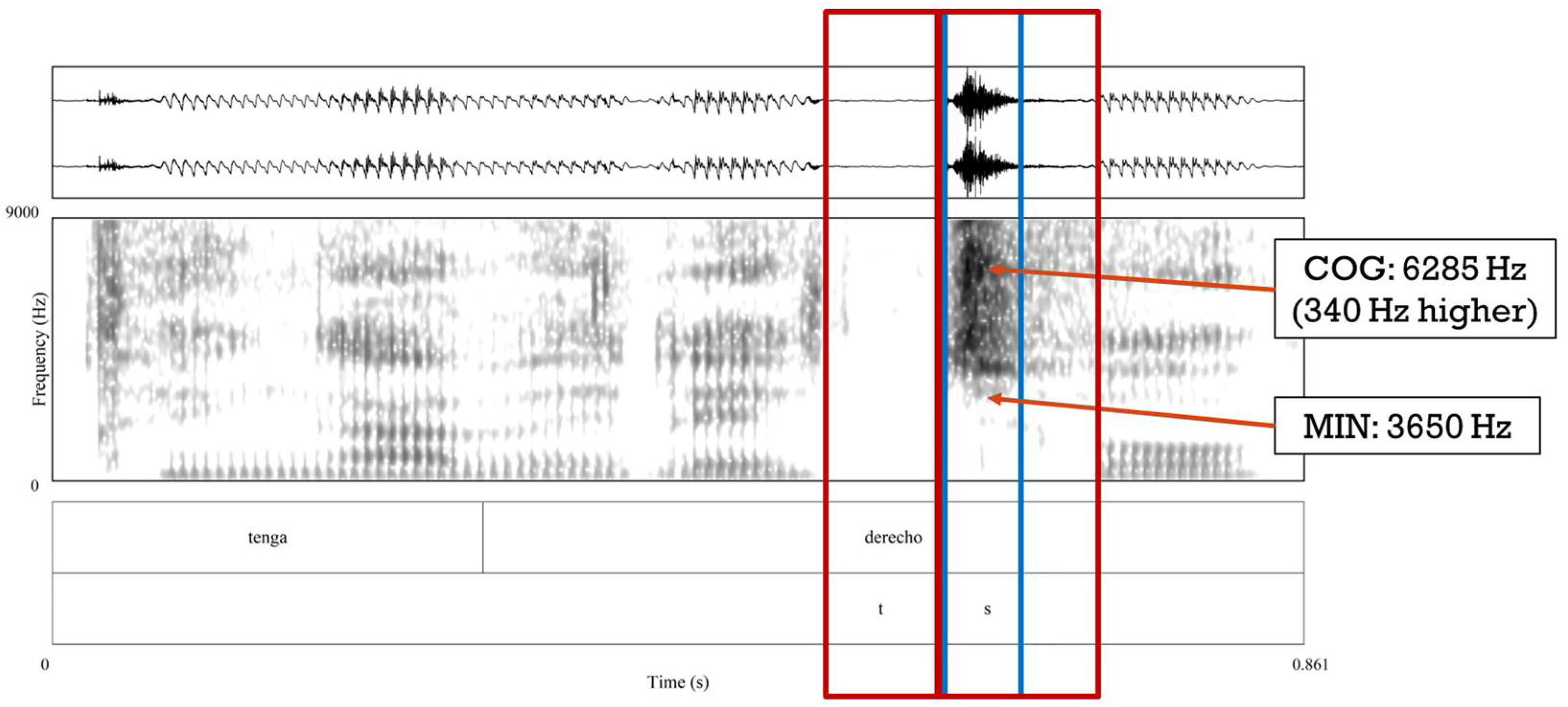

2.2. The Spanish Affricate and Acoustic Measures of Frication

2.3. Research Questions

3. Methodology

3.1. Speaker Selection

3.2. Acoustic Analysis of the Affricate

3.3. Dependent and Independent Variables

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

| Variable | Factor | Coefficient | Tokens | Frication as a % of Segment Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political party (p = 0.003) | Socialist (PSOE) | 0.024 | 1428 | 53.5% |

| Conservative (PP) | −0.024 | 1747 | 48.4% | |

| Range (%) | 5.1% | |||

| Preceding context (p < 0.001) | Consonant | 0.014 | 235 | 52.8% |

| Back vowel | 0.002 | 1783 | 51.5% | |

| Central vowel | 0.001 | 79 | 50.8% | |

| Front vowel | −0.016 | 1078 | 48.9% | |

| Range (%) | 3.9% | |||

| Following vowel (p < 0.001) | Front vowel | 0.014 | 502 | 52.3% |

| Central vowel | −0.006 | 1036 | 50.9% | |

| Back vowel | −0.008 | 1637 | 50.1% | |

| Range (%) | 2.2% | |||

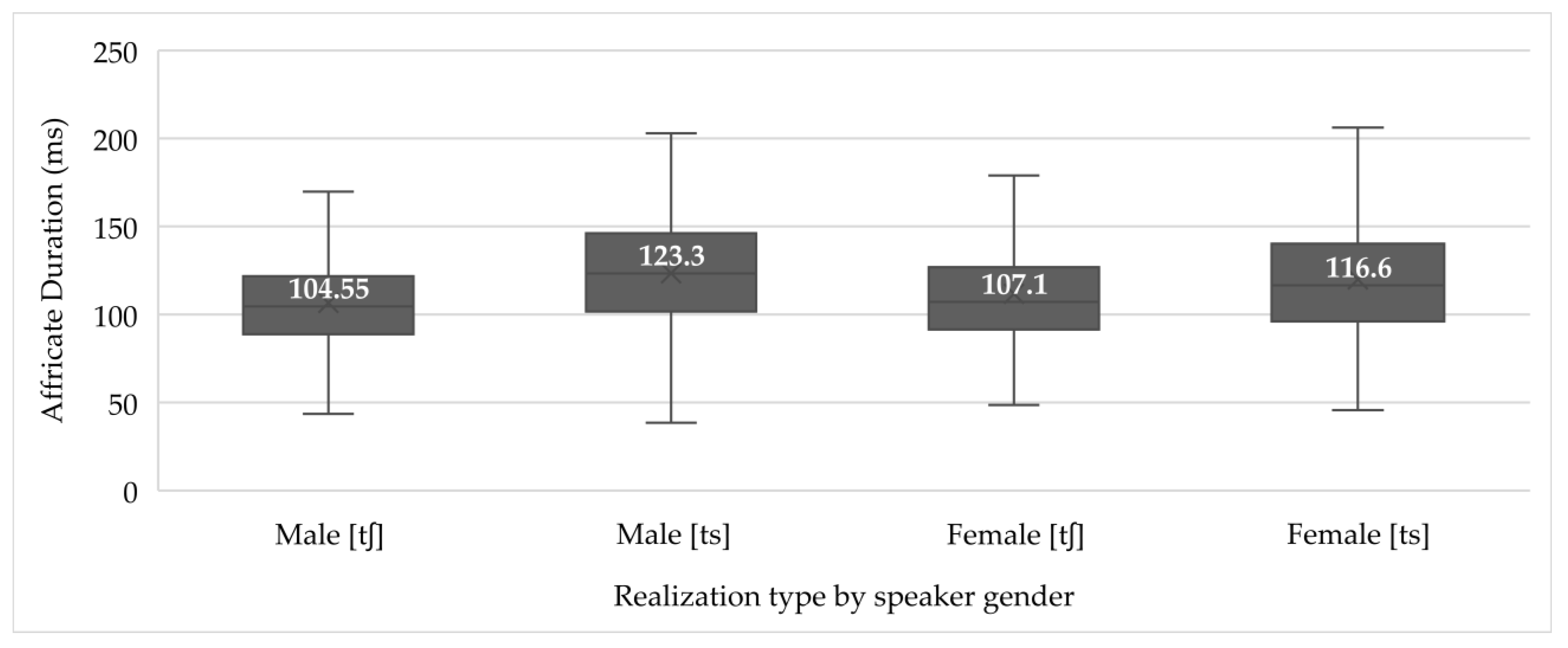

| Realization type (p < 0.001) | [ts] | 0.008 | 868 | 51.6% |

| [tʃ] | −0.008 | 2307 | 50.3% | |

| Range (%) | 1.3% | |||

| Speech context (p = 0.001) | Unscripted male | 0.006 | 1047 | 51.1% |

| Unscripted female | 0.001 | 988 | 51.1% | |

| Scripted speech | −0.006 | 1140 | 50.0% | |

| Range (%) | 1.1% | |||

| Lexical frequency (p < 0.001) | Continuous | Coefficient | ||

| +1 | 0.001 | |||

| Scaled following vowel F1 (p = 0.010) | Continuous | Coefficient | ||

| +1 | 0.001 | |||

| n = 3175; df = 15; Log-likelihood = 3784; AIC = −7538; R2 fixed = 0.221; R2 total = 0.323 | ||||

| Variable | Factor | Coefficient | Tokens | Rescaled COG (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City (p = 0.001) | Madrid | 63.838 | 793 | 4101.1 |

| Malaga | −5.442 | 695 | 4032.8 | |

| Cordoba | −14.479 | 717 | 4024.1 | |

| Seville | −43.917 | 970 | 3976.8 | |

| Range (Hz) | 124.3 | |||

| Preceding context (p < 0.001) | Central vowel | 35.486 | 79 | 4110.5 |

| Alveolar | 8.322 | 235 | 4106.0 | |

| Front vowel | 1.517 | 1078 | 4043.9 | |

| Back vowel | −45.326 | 1783 | 4009.4 | |

| Range (Hz) | 101.1 | |||

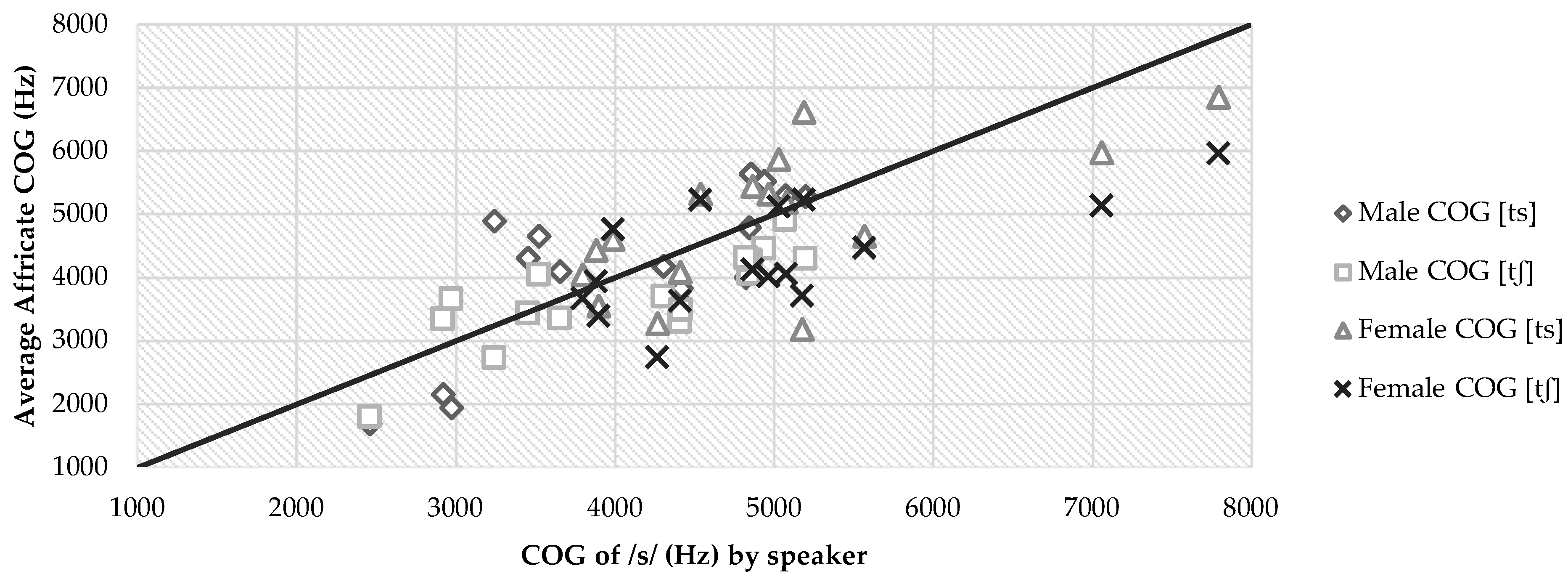

| Realization coding (p < 0.001) | [ts] | 26.8 | 868 | 4081.4 |

| [tʃ] | −26.8 | 2307 | 4011.7 | |

| Range (Hz) | 69.7 | |||

| Following vowel (p = 0.010) | Front | 10.21 | 502 | 4073.0 |

| Central | 8.4 | 1036 | 4050.1 | |

| Back | −18.61 | 1637 | 4005.7 | |

| Range (Hz) | 67.3 | |||

| Tonicity (p = 0.001) | Tonic | 19.406 | 543 | 4077.4 |

| Atonic | −19.406 | 2632 | 4021.2 | |

| Range (Hz) | 56.2 | |||

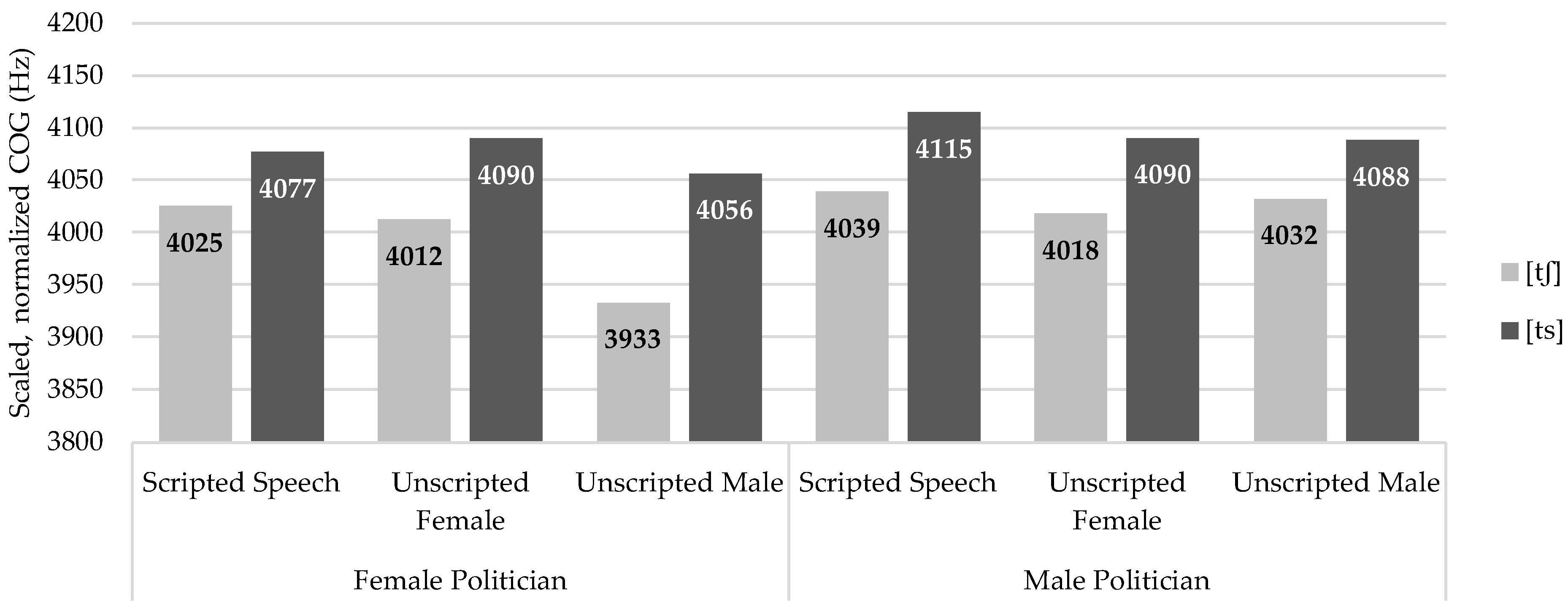

| Speech context (p < 0.001) | Scripted | 16.916 | 1140 | 4047.9 |

| Female Unscripted | −0.303 | 988 | 4037.7 | |

| Male Unscripted | −16.612 | 1047 | 4005.6 | |

| Range (Hz) | 42.3 | |||

| Gender (p = 0.021) | Men | 20.921 | 1521 | 4041.7 |

| Women | -20.921 | 1654 | 4020.8 | |

| Range (Hz) | 21 | |||

| Interaction: Speaker Gender * Speech context (p = 0.001) | Male:Scripted | 18.081 | 593 | 4050.0 |

| Female:Scripted | 13.735 | 547 | 4045.6 | |

| Female:Female Interloc | 4.345 | 542 | 4042.0 | |

| Male:Male Interloc | −4.345 | 482 | 4039.9 | |

| Male:Female Interloc | −13.735 | 446 | 4032.5 | |

| Female:Male Interloc | −18.081 | 565 | 3976.4 | |

| Range (Hz) | 73.6 | |||

| Scaled normalized following vowel F2 (p = 0.015) | Continuous | Coefficient | ||

| 1 | 0.026 | |||

| n = 3175; df = 20; Log-likelihood = −21,322; AIC = 42,683; R2 Fixed = 0.105; R2 Total = 0.148 | ||||

| Variable | Factor | Coefficient | Tokens | % [ts] | Factor Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

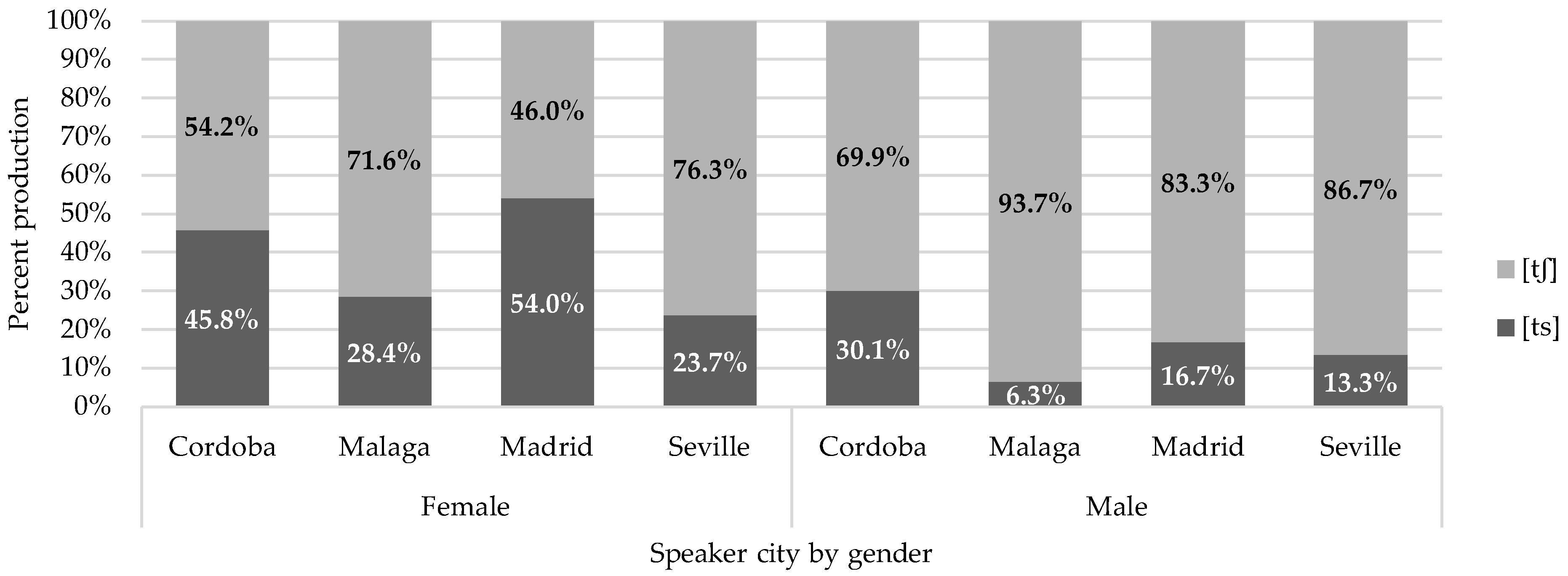

| Gender (p = 0.001) | Female | 0.827 | 1654 | 37.7% | 0.696 |

| Male | −0.827 | 1521 | 16.1% | 0.304 | |

| Range | 39.2 | ||||

| Preceding context (p < 0.001) | Consonant | 0.663 | 235 | 49.4% | 0.660 |

| Front vowel | 0.329 | 1078 | 30.5% | 0.581 | |

| Central vowel | −0.34 | 79 | 29.1% | 0.416 | |

| Back vowel | −0.652 | 1783 | 22.4% | 0.343 | |

| Range | 31.7 | ||||

| Following vowel (p < 0.001) | Central | 0.335 | 1036 | 35.5% | 0.583 |

| Front | 0.097 | 502 | 29.3% | 0.524 | |

| Back | −0.432 | 1637 | 21.6% | 0.394 | |

| Range | 18.9 | ||||

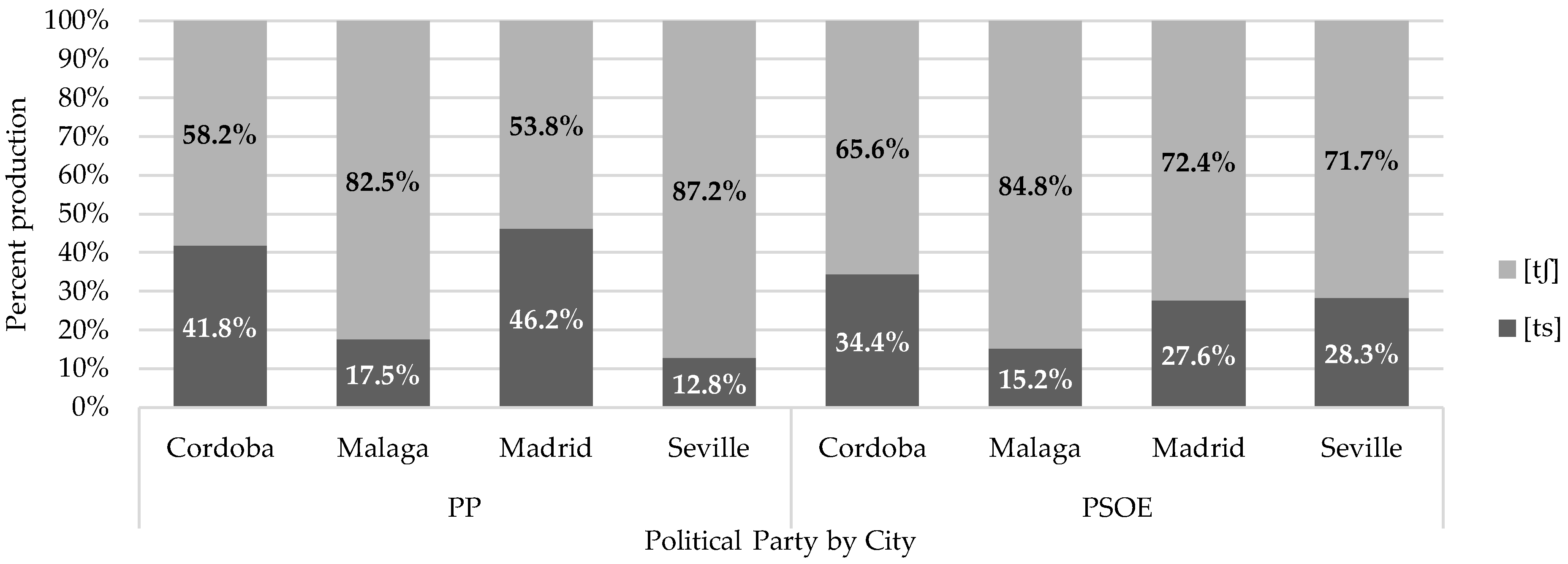

| City (p = 0.270) † | Cordoba | 0.515 | 717 | 38.4% | 0.626 |

| Madrid | 0.452 | 793 | 37.3% | 0.611 | |

| Seville | −0.362 | 970 | 18.9% | 0.411 | |

| Malaga | −0.605 | 695 | 16.4% | 0.353 | |

| Range | 27.3 | ||||

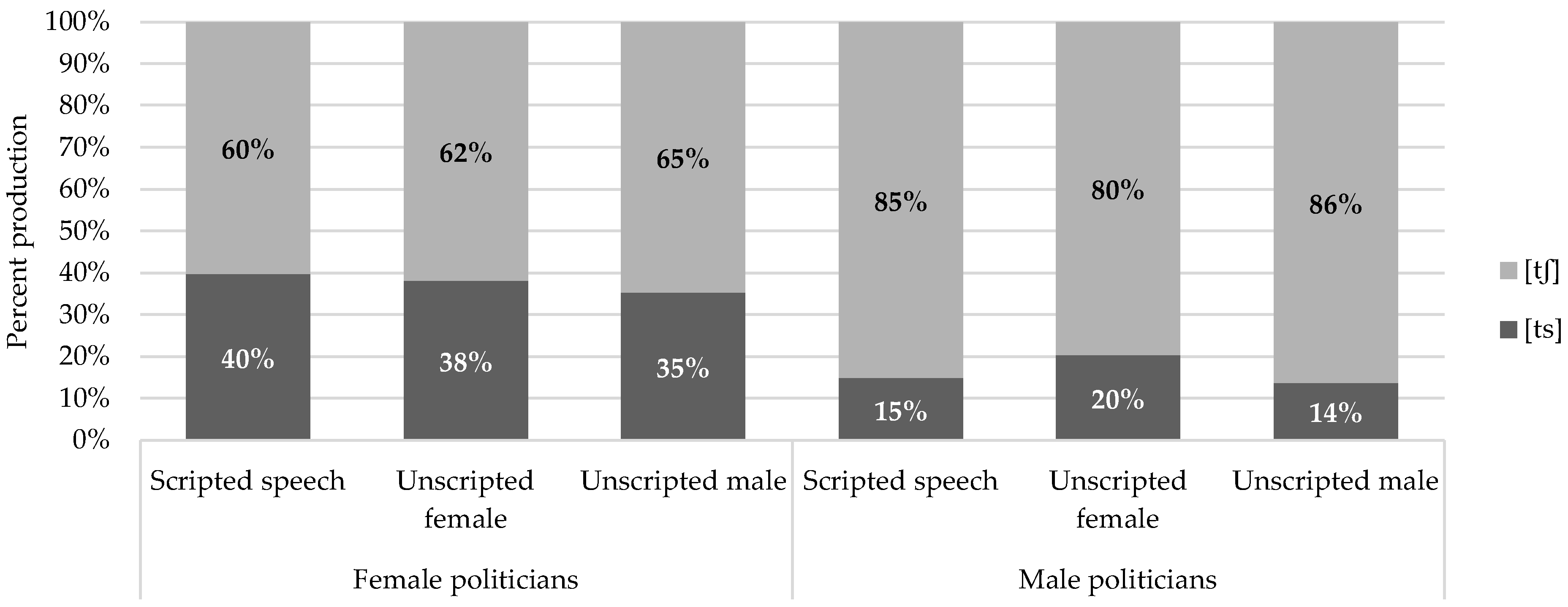

| Speech context (p = 0.085) † | Unscripted female | 0.146 | 988 | 30.2% | 0.536 |

| Scripted speech | 0.036 | 1140 | 26.8% | 0.509 | |

| Unscripted male | −0.182 | 1047 | 25.3% | 0.455 | |

| Range | 8.1 | ||||

| Speaker Gender * Speech context | Female:Scripted | 0.172 | 547 | 0.397 | 0.543 |

| (p = 0.037) | Female:Female Interloc | 0.14 | 542 | 0.382 | 0.535 |

| Female:Male Interloc | 0.031 | 565 | 0.352 | 0.508 | |

| Male:Female Interloc | −0.031 | 446 | 0.204 | 0.492 | |

| Male:Scripted | −0.14 | 593 | 0.148 | 0.465 | |

| Male:Male Interloc | −0.172 | 482 | 0.137 | 0.457 | |

| Range (Hz) | 8.6 | ||||

| Scaled COG of frication (p < 0.001) | Continuous | ||||

| +1 | 0.001 | ||||

| Percent frication (p < 0.001) | Continuous | ||||

| +1 | 3.362 | ||||

| Normalized F1 of following vowel | Continuous | ||||

| (p = 0.016) | +1 | 0.017 | |||

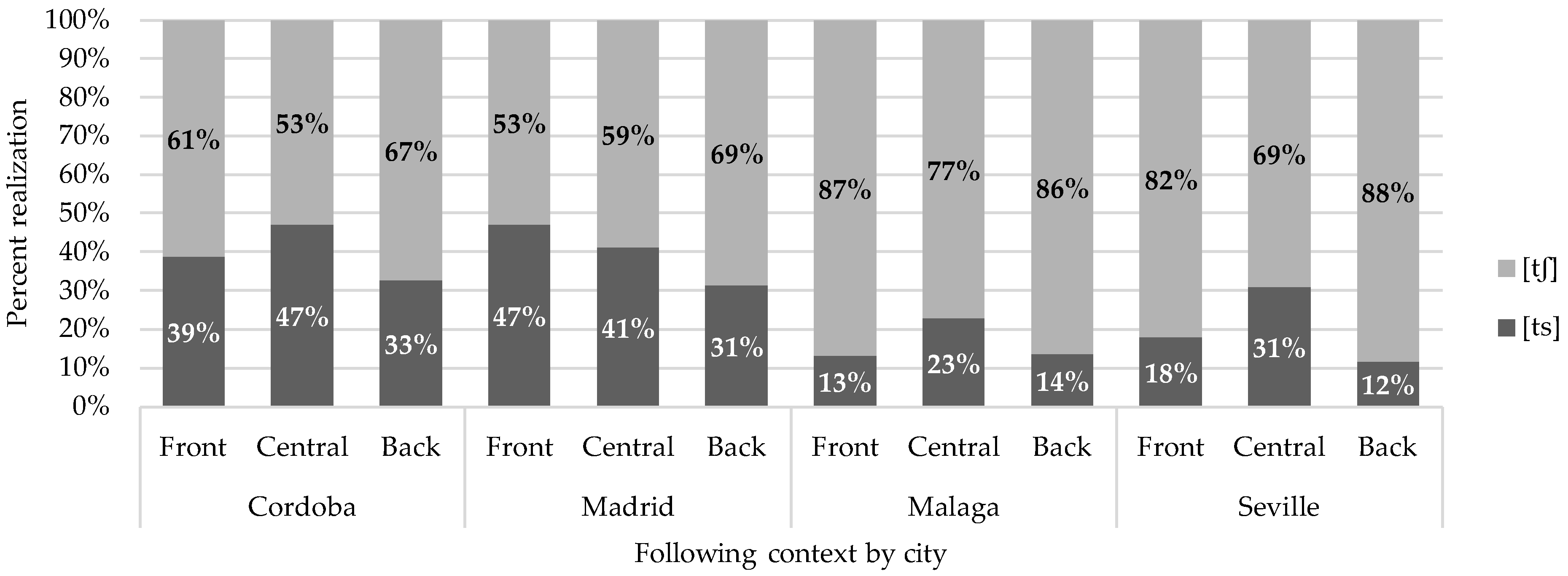

| City * Following Context (p = 0.007) | |||||

| n = 3175; df = 25; Log-likelihood = −1391; AIC = 2832; R2 fixed = 0.262; R2 = 0.485 | |||||

5. Discussion

5.1. Phonetic Variation in the Affricate

5.2. Affricate Variation in Peninsular Political Speech

5.3. A Labovian Sociolinguistic Marker

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A correlation has also been pointed out between affricate productions of [ts] in the wake of /s/ reduction before /t/ and a fronted variant associated with the affricate /tʃ/, by researchers including Torreira (2006), Ruch (2012), Del Saz (2019, 2023), and Vida-Castro (2022). Research in this vein has also begun to examine the production of [ts] deriving from affricates. For example, Vida-Castro and Villena-Ponsoda (2016) showed that a higher COG for center of gravity is more likely to receive perception as /tʃ/ rather than /st/ in Malaga, Spain. |

| 2 | As Cruz-Ortiz (2022) and Pollock and Wheeler (2022) have pointed out, among others, the elision of intervocalic /d/ occurs much more among politicians than even among rural and working-class speakers across Spain, suggesting that there is an association between “speaking like a politician” and eliding in these contexts. Given the demographics of the current study, it is not yet clear if the same is true for the alveolar affricate—however, Pollock (2023a), who included the alveolar affricate in a composite of regional features used by politicians, found that listeners rate it as more urban, educated, likeable, and less Andalusian than the post-alveolar variant, suggesting social associations with the form. |

| 3 | However, see the recent Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics for an overview of the many ways in which these frequency-based trends have been explored in greater nuance, as well as contexts in which frequency effects have been found not to play a major role (Díaz-Campos and Balasch 2023). |

| 4 | It is also important to note that there is evidence to suggest that gendered differences can also vary cross-linguistically. Fuchs and Toda (2010) found that sibilant productions differed between gendered groups in English and German, which may have resulted from differences in the fricative inventory of the two languages. Additionally, Munson (2011) identified perceived talker gender as playing an important role in differentiating /s/ from /∫/, showing that there are a number of biological and sociocultural influences on sibilant fricative production that merit further study among Spanish politicians. |

References

- Abramson, Arthur S., and Leigh Lisker. 1972. Voice-timing perception in Spanish word-initial stops. Journal of Phonetics 1: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Manuel. 2019. Language hybridism: On the origin of interdialectal forms. In Language Variation—European Perspectives VII: Selected Papers from the Ninth International Conference on Language Variation in Europe (ICLaVE 9), Malaga, June 2017 [Studies in Language Variation 22]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Alan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2023. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Version 6.0.35. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Bradley, Travis G., and Claire J. Lozano. 2022. Language Contact and Phonological Innovation in the Voiced Prepalatal Obstruents of Judeo-Spanish. Languages 7: 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, Mary, and Kira Hall. 2005. Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach. Discourse Studies 7: 585–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 1998. The Emergent Lexicon. Chicago Linguistic Society 34: 421–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2002. Word frequency and context of use in the lexical diffusion of phonetically conditioned sound change. Language Variation and Change 14: 261–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2001. Language, situation, and the relational self: Theorizing dialect-style in sociolinguistics. In Style and Sociolinguistic Variation. Edited by Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ortiz, Rocío. 2022. Sociofonética andaluza. Caracterización lingüística de los presidentes y ministros de Andalucía en el Gobierno de España (1923–2011). Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Del Saz, María. 2019. From postaspiration to affrication: New phonetic contexts in western Andalusian Spanish. Paper presented at 19th ICPhS, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Del Saz, María. 2023. (In)complete neutralization in Western Andalusian Spanish. Estudios de Fonética Experimental 32: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, and Sonia Balasch. 2023. The Handbook of Usage-Based Linguistics. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, Molly Cole, and Matthew Pollock. 2023. Re-conceptualizing affricate variation in Caracas Spanish. Hispania 106: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, Stephen Fafulas, and Michael Gradoville. 2018. Stable variation or change in progress? A sociolinguistic analysis of the alternation between para and pa. In Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Edited by Jeremy King and Sandro Sessarego. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Molina Ortés, Elena. 2020. ¿Cómo hablan los presentadores andaluces en televisión? Percepción de los espectadores y análisis lingüístico de la posible variación (socio)estilística en los medios. LinRed 17: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Tanya. 2014. A Socio-Phonetic Examination of Co-Articulation in Chilean Public Speech (Document No. AAI3665473). Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Tanya. 2018. Lexical Frequency Effects in Chilean Spanish Affricate Fronting. Southern Journal of Linguistics 41: 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Susanne, and Martine Toda. 2010. Do differences in male versus female /s/ reflect biological or sociophonetic factors? In Turbulent Sounds: An Interdisciplinary Guide. Edited by Susanne Fuchs, Marzena Zygis and Martine Toda. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, Nikolas Coupland, and Justine Coupland. 1991. Accommodation theory: Communication, context, and consequence. In The Contexts of Accommodation. Edited by Howard Giles, Nikolas Coupland and Justine Coupland. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Matthew, Paul Barthmaier, and Kathy Sands. 2002. Cross-linguistic acoustic study of voiceless fricatives. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 32: 141–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Lew, Lauren, Rebecca Starr, and Elizabeth Coppock. 2012. Style-shifting in the U. S. Congress: The vowels of “Iraq(i)”. In Style-Shifting in Public: New Perspectives on Stylistic Variation. Edited by Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Lew, Lauren, Ruth Friskney, and James M. Scobbie. 2017. Accommodation or political identity: Scottish members of the UK Parliament. Language Variation and Change 29: 341–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Jonathan. 2007. Evidence for a relationship between synchronic variability and diachronic change in the Queen’s annual Christmas broadcasts. Laboratory Phonology 9: 125–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer, Stefanie Jannedy, and Norma Mendoza-Denton. 2010. Oprah and /ay/: Lexical Frequency, Referee Design, and Style. In The Routledge Sociolinguistics Reader. Edited by Miriam Meyerhoff and Erik Schleef. New York: Routledge, pp. 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez-Barahona, Marisol, and Darío Fuentes-Grandón. 2018. Realizaciones de los fonemas /tʃ/ y /ʈ͡ʂ/ en el chedungun hablado por niños bilingües del alto Biobío: Un análisis espectrográfico. Literatura y Lingüística 37: 253–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and José María Jiménez-Cano. 2003. Broadcasting standardization: An analysis of the linguistic normalization process in Murcian Spanish. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 321–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. 2010. Speaker design practices in political discourse: A case study. Language and Communication 30: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, Juan Manuel, and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. 2013. The effects of public and individual language attitudes on intra-speaker variation: A case study of style-shifting. Multilingua 31: 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero de Haro, Alfredo. 2017a. Four mid back vowels in Eastern Andalusian Spanish. Zeitschrift fur romanische Philologie 133: 82–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero de Haro, Alfredo. 2017b. The phonetics and phonology of Eastern Andalusian Spanish: A review of literature from 1881 to 2016. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura 22: 313–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, Nicole. 2017. “My Presiden(T) And Firs(T) Lady Were Black”: Style, Context, And Coronal Stop Deletion in The Speech of Barack And Michelle Obama. American Speech 92: 459–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hualde, José Ignacio, and Sonia Colina. 2014. Los Sonidos del español. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, José Ignacio. 2005. The Sounds of Spanish. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. 2019. Watson Speech to Text Demo. [Computer Program]. Available online: https://speech-to-text-demo.ng.bluemix.net/ (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2009. Getting off the GoldVarb Standard: Introducing Rbrul for Mixed-Effects Variable Rule Analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel Ezra. 2014. Progress in Regression: Why Natural Language Data Calls For Mixed-Effects Models. Available online: http://www.danielezrajohnson.com/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Jongman, Allard. 1989. Duration of frication noise required for identification of English fricatives. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 85: 1718–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongman, Allard, Ratree Wayland, and Serena Wong. 2000. Acoustic characteristics of English fricatives. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 108: 1252–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Tyler, and Erik R. Thomas. 2010. Vowels: Vowel Manipulation, Normalization, and Plotting in R. R Package, Version 1.1. Available online: http://ncslaap.lib.ncsu.edu/tools/norm/ (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Kirkham, Sam, and Emma Moore. 2016. Constructing social meaning in political discourse: Phonetic variation and verb processes in Ed Miliband’s speeches. Language in Society 45: 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William, Ingrid Rosenfelder, and Josef Fruehwald. 2013. One Hundred Years of Sound Change in Philadelphia: Linear Incrementation, Reversal, and Reanalysis. Language 89: 30–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Aijun, and Zhiqiang Li. 2019. Spectral Analysis of Sibilant Fricatives and the Ling Sound Test for Speakers of Chinese Dialects. ICPHS Full Papers. pp. 3026–30. Available online: https://icphs2019.org/icphs2019-fullpapers/ (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Lobanov, Boris M. 1971. Classification of Russian vowels spoken by different listeners. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 49: 606–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaro, Natalia. 2022. The Effect of Language Contact on /tʃ/ Deaffrication in Spanish from the US–Mexico Borderland. Languages 7: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melguizo-Moreno, Elisabeth. 2006. La fricatización de /č/ en una comunidad de hablantes granadina. Interlingüística 17: 748–57. [Google Scholar]

- Munson, Benjamin. 2011. The influence of actual and imputed talker gender on fricative perception, revisited. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 130: 2631–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Méndez, Eva. 2022. Variation in Spanish /s/: Overview and New Perspectives. Languages 7: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, Ralph. 2002. A History of the Spanish Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Matthew. 2023a. Performing Andalusian in Political Speech: Political Party and Sociophonetic Patterns Across Production and Perception. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Matthew. 2023b. Toeing the Party Line: Indexing Party Identity through Dialectal Phonetic Features in Spanish Political Discourse. Languages 8: 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Matthew, and Jamelyn A. Wheeler. 2022. Syllable-final /s/ and intervocalic /d/ elision in Andalusia: The Formation of Susana Díaz’s Regional Identity in Political Discourse. Language and Communication 87: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Matthew. forthcoming. Politics, Variation, and Politeness on Andalusian Twitter (X): The second-person plural in Peninsular Spanish identity construction. In Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Pollock, Matthew, and Jamelyn A. Wheeler. forthcoming. Language, politics, and power: A sociophonetic comparison of political and community norms in Galician Spanish. In Issues in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rama, José, Lisa Zanotti, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte, and Andrés Santana. 2021. Vox: The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Recasens, Daniel, and Aina Espinosa. 2007. An electropalatographic and acoustic study of affricates and fricatives in two Catalan dialects. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37: 143–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recasens, Daniel. 2018. Coarticulation. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Edited by Mark Aronoff. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, Brendan. 2020. El [ʃ]oquero: /tʃ/ Variation in Huelva Capital and Surrounding Towns. Estudios de Fonética Experimental 29: 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ruch, Hanna. 2012. Affrication of /st/-clusters in Western Andalusian Spanish: Variation and change from sociophonetic point of view. In Proceedings of Sociophonetics, at the Crossroads of Speech Variation, Processing and Communication. Edited by Silvia Calamai, Chiara Celata and Luca Ciucci. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Samper-Padilla, José Antonio. 2011. Socio-phonological Variation and change in Spain. In The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling-Estes, Natalie. 2013. Investigating stylistic variation. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Edited by Jack Chambers, Peter Trudgill and Natalie Schilling-Estes. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Devyani. 2018. Style dominance: Attention, audience, and the ‘real me’. Language in Society 47: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical Order and The Dialectics of Sociolinguistic life. Language and Communication 23: 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2012. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Toda, Martine. 2007. Speaker normalization of fricative noise: Considerations on language-specific contrast. Paper presented at 16th International Congress on Phonetic Sciences, Saarbrucken, Germany, August 6–10; pp. 825–28. [Google Scholar]

- Torrano Moreno, Laura. 2017. Variación y cambio sociolingüístico en una comunidad de habla local: El caso de la variable (ch) y los factores ontogenético y generolectal en Ricote. Tonos Digital 33. [Google Scholar]

- Torreira, Francisco. 2006. Coarticulation between aspirated-s and voiceless stops in Spanish: An interdialectal comparison. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and A. Jacqueline Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 113–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vida-Castro, Matilde. 2022. On competing indexicalities in southern Peninsular Spanish. A sociophonetic and perceptual analysis of affricate [ts] through time. Language Variation and Change 34: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida-Castro, Matilde, and Juan-Andrés Villena-Ponsoda. 2016. Percepción y análisis de pistas en la discriminación alofónica: Fusión y escisión en el estudio sociolingüístico de la ciudad de Málaga: Informe preliminar. In 53 reflexiones sobre aspectos de la fonética y otros temas de lingüística. Edited by Anna Maria Fernández Planas. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona Press, pp. 131–37. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 2008. Sociolinguistic patterns of Andalusian Spanish. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2008: 139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Ponsoda, Juan Andrés. 2013. Actos de identidad: ¿Por qué persiste el uso de los rasgos lingüísticos de bajo prestigio social? Divergencia geográfica y social en el español urbano de Andalucía. In Estudios Descriptivos y Aplicados Sobre el Andaluz. Edited by Rosario Guillén Stuil. Seville: The University of Seville Press, pp. 173–207. [Google Scholar]

| /s/ | /ʃ/ | |||

| Language | Duration (ms) | COG (Hz) | Duration (ms) | COG (Hz) |

| 1. Aleut | 361.8 | 5219 | - | - |

| 2. Apache | 172.3 | 5461 | 175.9 | 4859 |

| 3. Chickasaw | 123.6 | 5163 | 112.8 | 4679 |

| 4. Gaelic | 130.4 | 4884 | 110.7 | 4396 |

| 5. Hupa | 276.4 | 4797 | 217.7 | 4440 |

| 6. Montana Salish | 171.8 | 4601 | 178.9 | 4134 |

| 7. Toda | 198.3 | 4529 | 239.6 | 4704 |

| Average | 204.9 | 4950.6 | 172.6 | 4535.3 |

| standard deviation | 79.4 | 317.5 | 48.3 | 239.2 |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | Frication period COG (Hz) | Continuous | |||

| Percent frication duration | Continuous | ||||

| Place of production | Alveolar [ts] | Post-alveolar [tʃ] | |||

| Independent variables | Preceding context | Front vowel | Central vowel | Back vowel | Alveolar consonant |

| Following vowel type | Front | Central | Back | ||

| Following vowel F1 (Hz) | Continuous | ||||

| Tonicity | Tonic | Atonic | |||

| Lexical frequency | Continuous | ||||

| City | Seville | Cordoba | Malaga | Madrid | |

| Gender | Male | Female | |||

| Party | Left (PSOE) | Right (PP) | |||

| Context | Scripted | Unscripted male | Unscripted female | ||

| Random effects | Speaker | n = 32 | |||

| Lexeme | n = 228 | ||||

| Production | Count | COG | Scaled, Normalized COG | Duration | Percent Frication | Scaled, Normalized F1 (next vowel) | Scaled, Normalized F2 (next vowel) |

| [tʃ] | 2307 | 3979 Hz | 4012 Hz | 108.9 ms | 50.3% | 418.9 Hz | 1422.5 Hz |

| [ts] | 868 | 4783 Hz | 4081 Hz | 119.9 ms | 51.6% | 467.8 Hz | 1491.2 Hz |

| All /tʃ/ tokens | 3175 (33/file) | 4199 Hz | 4030 Hz | 111.9 ms | 50.7% | 432.3 Hz | 1441.3 Hz |

| All /s/ tokens | 3466 (35/file) | 4610 Hz | - | 86.9 ms | - | - | - |

| Language | /s/ Duration | COG | /ʃ/ Duration | COG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Aleut | 361.8 | 5219 | - | - |

| 2. Apache | 172.3 | 5461 | 175.9 | 4859 |

| 3. Chickasaw | 123.6 | 5163 | 112.8 | 4679 |

| 4. Gaelic | 130.4 | 4884 | 110.7 | 4396 |

| 5. Hupa | 276.4 | 4797 | 217.7 | 4440 |

| 6. Montana Salish | 171.8 | 4601 | 178.9 | 4134 |

| 7. Toda | 198.3 | 4529 | 239.6 | 4704 |

| Average | 204.9 | 4950.6 | 172.6 | 4535.3 |

| st.dev. | 79.4 | 317.5 | 48.3 | 239.2 |

| Peninsular Spanish | [ts] duration | COG | [tʃ] duration | COG |

| 8. Frication portion | 61.8 | 4783.4 | 54.5 | 3978.4 |

| 8.1. Total for affricate | 140.3 | 127.4 | ||

| Overall average | 187.1 | 4929.7 | 155.7 | 4455.8 |

| st.dev. | 94.1 | 323.0 | 65.7 | 318.7 |

| # | Variable Name | Frication Percent (Favor Higher % Frication) | Center of Gravity (Favor Higher COG) | Realization Coding (Favor [ts]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic Variables | ||||

| 1 | Frication Percent | - | Greater percent | |

| 2 | Center of Gravity | - | Higher COG | |

| 3 | Realization Type | [ts] | [ts] | |

| 4 | Preceding Context | Consonants, back and central vowels | Consonants, front and central vowels | Consonants and front vowels |

| 5 | Following Context | Front vowels | Front and central vowels | Front and central vowels |

| 6 | Lexical Frequency | More frequent | - | - |

| 7 | Following Vowel F2 (normalized and scaled) | - | Higher F2 | - |

| 8 | Following Vowel F1 (normalized and scaled) | Higher F1 | - | Higher F1 |

| 9 | Tonicity | - | Tonic syllables | - |

| Extralinguistic Variables | ||||

| 10 | City | - | Madrid | Cordoba and Madrid |

| 11 | Political Party | PSOE politicians | - | - |

| 12 | Speech Context | Male and female unscripted | Scripted and female unscripted | Scripted and female unscripted |

| 13 | Gender | - | Men | Women |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pollock, M. Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]isimas gracias: A Sociophonetic Study of the Alveolar Affricate in Peninsular Spanish Political Speech. Languages 2024, 9, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060218

Pollock M. Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]isimas gracias: A Sociophonetic Study of the Alveolar Affricate in Peninsular Spanish Political Speech. Languages. 2024; 9(6):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060218

Chicago/Turabian StylePollock, Matthew. 2024. "Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]isimas gracias: A Sociophonetic Study of the Alveolar Affricate in Peninsular Spanish Political Speech" Languages 9, no. 6: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060218

APA StylePollock, M. (2024). Buenas no[tʃ]es y mu[ts]isimas gracias: A Sociophonetic Study of the Alveolar Affricate in Peninsular Spanish Political Speech. Languages, 9(6), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060218