Differential Object Marking in Structurally Complex Contexts in Spanish: Evidence from Bilingual and Monolingual Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Differential Object Marking and Relative Clauses in Spanish and Catalan

| (1) | a. Animacy scale: human > animate > inanimate; |

| b. Definiteness scale: personal pronoun > proper name > definite NP > non | |

| definite, specific NP > non-definite, non-specific NP. |

| (2) | Matrix clauses | |

| a. | Carla vio a la niña. [+animate, +human] | |

| Carla saw DOM the girl. | ||

| ‘Carla saw the girl.’ | ||

| b. | Carla vio (a) la gata. [+animate, −human] | |

| Carla saw DOM the cat. | ||

| ‘Carla saw the cat.’ | ||

| c. | Carla vio la mesa. [−animate] | |

| Carla saw the table. | ||

| ‘Carla saw the table.’ | ||

| (3) | Subject relative clauses (SVO) | |

| a. | La gata que buscó a la niña entró inesperadamente. [+animate, +human] | |

| The cat that looked for DOM the girl entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The cat that looked for the girl entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| b. | La niña que buscó (a) la gata entró inesperadamente. [+animate, −human] | |

| The girl that looked for (DOM) the cat entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The girl that looked for the cat entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| (4) | Object relative clauses (OVS) | |

| a. | La gata que buscó la niña entró inesperadamente. [+animate, +human] | |

| The cat that looked for the girl entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The cat that the girl looked for entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| b. | La niña que buscó la gata entró inesperadamente. [+animate, −human] | |

| The girl that looked for the cat entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The girl that {the cat looked for/looked for the cat} entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| (5) | a. | La va veure a ella. [+human, +personal pronoun] |

| CL AUX saw DOM she | ||

| ‘He/she saw her.’ | ||

| b. | La Carla va veure la noia. [+animate, +human] | |

| The Carla AUX seen the girl | ||

| ‘Carla saw the girl.’ |

| (6) | Subject relative clauses (SVO) | |

| a. | La gata que va buscar la nena va entrar inesperadament. [+animate, +human] | |

| The cat that looked for the girl entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The cat that looked for the girl entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| b. | La nena que va buscar la gata va entrar inesperadament. [+animate, −human] | |

| The girl that looked for the cat entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The girl that looked for the cat entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| (7) | Object relative clauses (OVS) | |

| a. | La gata que va buscar la nena va entrar inesperadament. [+animate, −human] | |

| The cat that looked for the girl entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The cat that the girl looked for entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

| b. | La nena que va buscar la gata va entrar inesperadament. [+animate, +human] | |

| The girl that looked for the cat entered unexpectedly | ||

| ‘The girl that the cat looked for entered unexpectedly.’ | ||

1.2. Online Processing of DOM and RCs in Native and Bilingual Speakers

1.2.1. Differential Object Marking (DOM)

1.2.2. Relative Clauses (RCs)

1.3. The Study: Aims and Predictions

- 1.

- RQ1: What are the patterns of interpretation and processing of obligatory versus optional DOM in Spanish among monolingually raised Spanish speakers? What are the patterns observed in the case of Catalan–Spanish bilinguals?

- 2.

- RQ2: Are subject RCs easier to interpret and process than object RCs in Spanish? If so, is this ease of processing influenced by the presence or absence of DOM when interpreting and parsing relative clauses, both in monolinguals and bilinguals?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli and Procedure

| (8) | Subject RC (SVO) | |

| a. | La gorila que abrazó a la bióloga sonreía incesantemente. (animal S, human O) | |

| ‘The gorilla that hugged the biologist smiled unceasingly’ | ||

| b. | La bióloga que abrazó a la gorila sonreía incesantemente. (human S, animal O) | |

| ‘The biologist that hugged the gorilla smiled unceasingly’ | ||

| (9) | Object RC (OVS) | |

| a. | La gorila que abrazó la bióloga sonreía incesantemente. (animal O, human S) | |

| ‘The gorilla that the biologist hugged smiled unceasingly’ | ||

| b. | La bióloga que abrazó la gorila sonreía incesantemente. (human O, animal S) | |

| ‘The biologist that the gorilla hugged smiled unceasingly’ | ||

3. Results

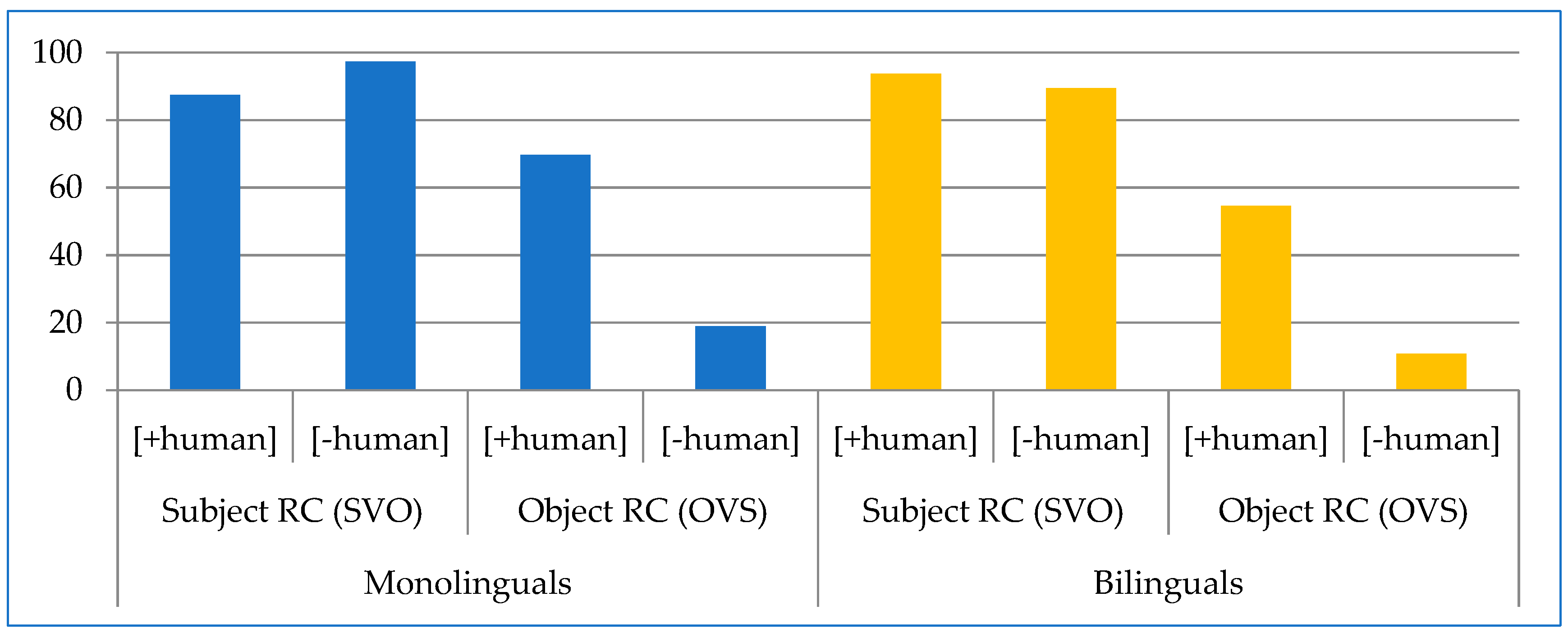

3.1. Content Comprehension and RC Interpretation Questions

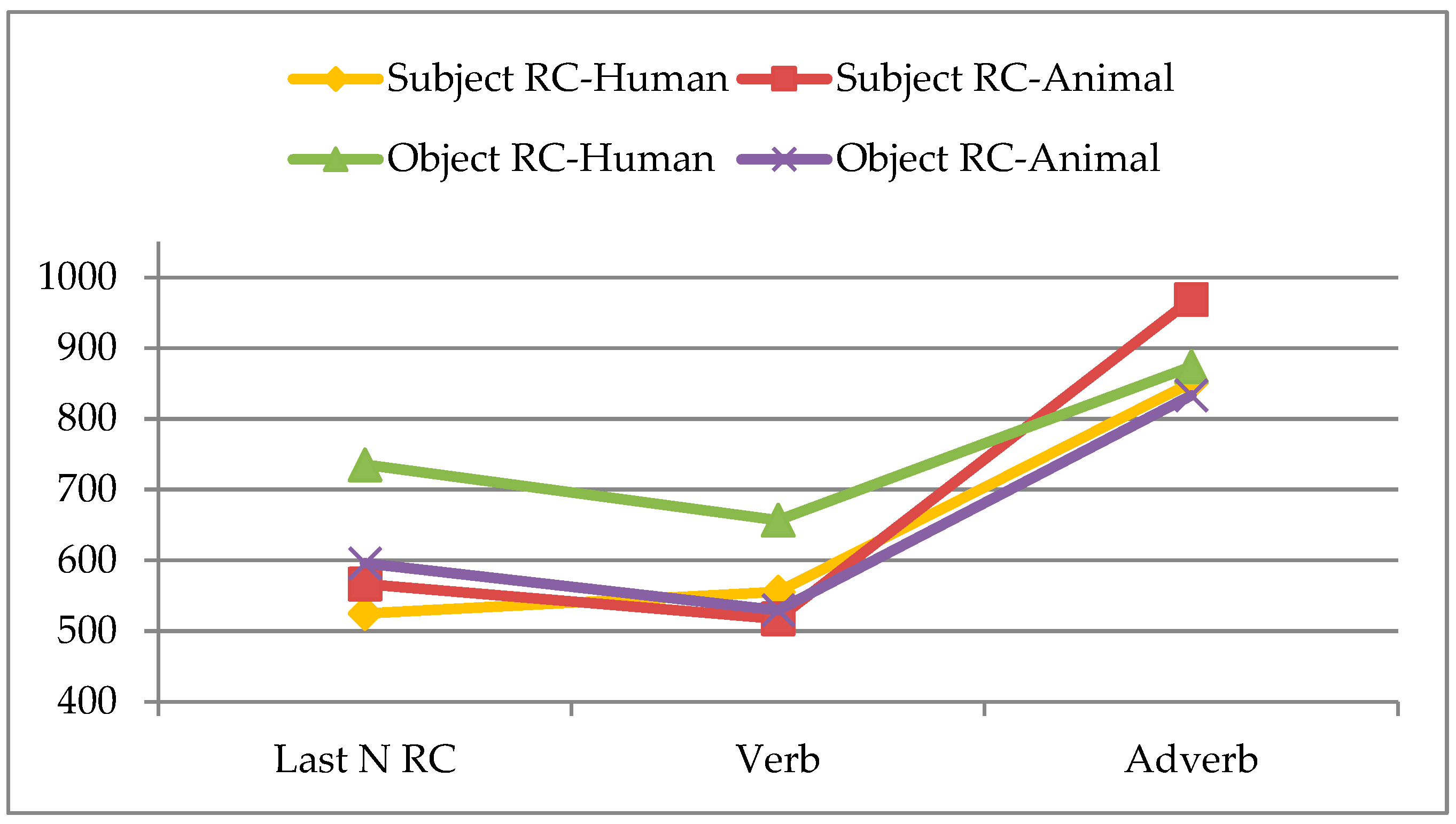

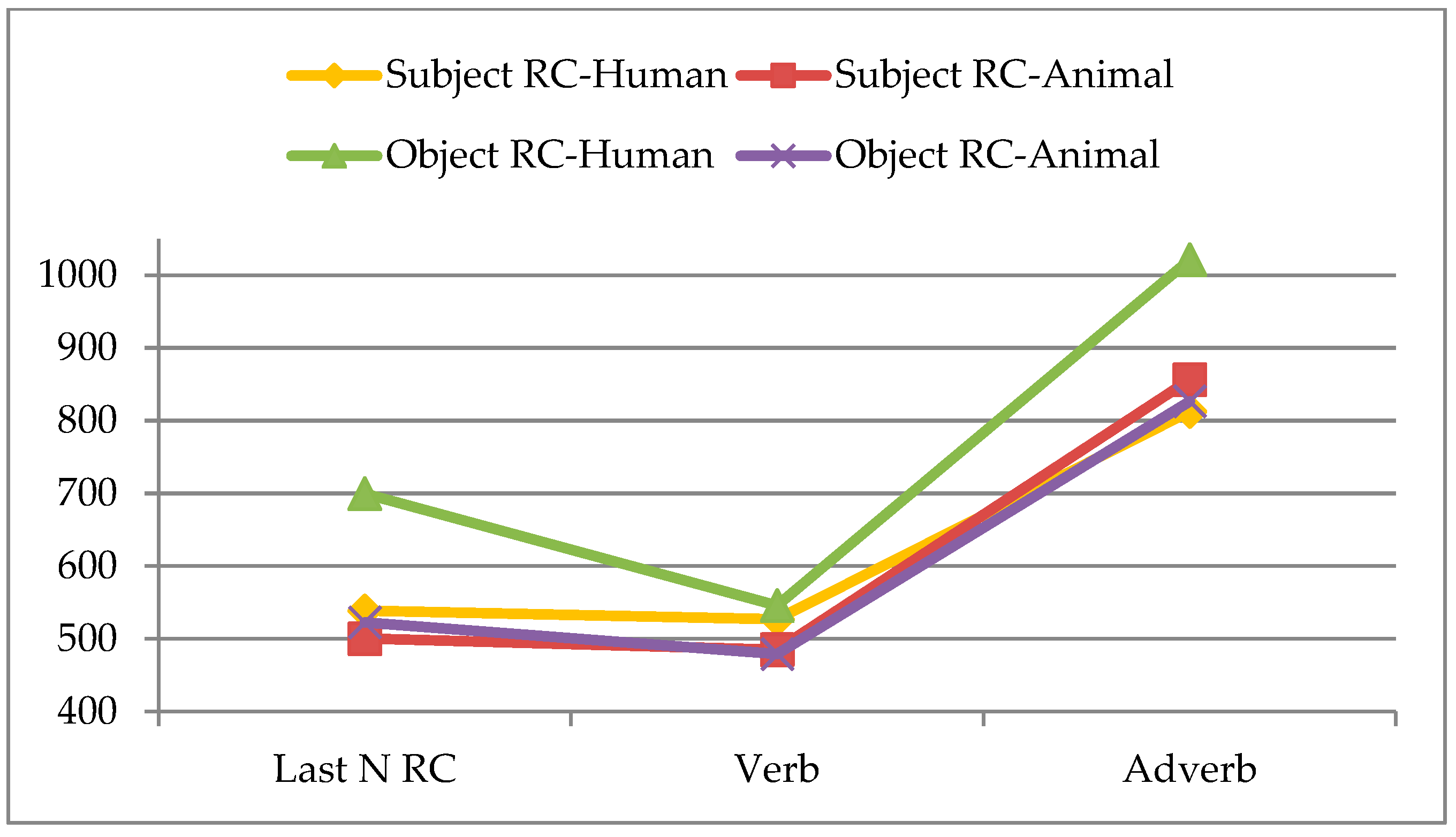

3.2. Reading Times

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Edad (Age): | Lugar de nacimiento (Place of birh): | ||||||||||||||

| Lugar de residencia actual (Current place of residence): | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Si no es donde naciste, indica desde cuándo vives en el lugar actual (If it is not where you were born, indicate how long you have lived in the current place): | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Lugar de nacimiento del padre (Father’s place of birth): | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Lugar de nacimiento de la madre (Mother’s place of birth): | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Indica a qué edad comenzaste a escuchar de forma continuada el castellano (at what age you began to listen to Spanish continuously) | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Indica a qué edad comenzaste a utilizar (hablar) el castellano: (at what age you started to use (speak) Spanish) | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Indica cómo y/o dónde aprendiste el castellano: (how and/or where you learned Spanish) | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Indica a qué edad comenzaste a escuchar de forma continuada el catalán: (at what age did you begin to listen to Catalan continuously) | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Indica a qué edad comenzaste a utilizar (hablar) el catalán: (at what age you started to use (speak) Catalan) | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Indica la lengua (castellano, ambas, otras) que habitualmente utilizas para hablar con: (Indicate the language (Spanish, both, others) that you usually use to speak with) | |||||||||||||||

| padre (father): | madre (mother): | hermano/as (siblings): | novio/a (boyfriend/girlfriend): | ||||||||||||

| 10. Si de pequeño hablabas con tus padres o hermanos en alguna otra lengua de la que utilizas actualmente, indica a qué edad se produjo el cambio (If when you were little you spoke with your parents or siblings in a language other than the one you currently use, indicate at what age the change occurred): | |||||||||||||||

| padre (father): | madre (mother): | hermano/as (siblings): | novio/a (boyfriend/girlfriend): | ||||||||||||

| 11. ¿Qué otras lenguas puedes utilizar/utilizas normalmente (hablar, leer, escribir)? (What other languages can you/do you normally use (speak, read, write)?) | |||||||||||||||

| 12.¿A qué edad iniciaste el aprendizaje formal de estas lenguas? (At what age did you start formally learning these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| 13. Señala con un círculo la opción que mejor te representa en cada una de las siguientes preguntas (Please circle the option that best represents you for each of the following questions): | |||||||||||||||

| a. ¿Qué nivel de comprensión oral tienes en cada una de estas lenguas? (What level of oral comprehension do you have in each of these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| English: | perfectly | good | sufficient | very little | |||||||||||

| French: | perfectly | good | sufficient | very little | |||||||||||

| Spanish: | perfectly | good | sufficient | very little | |||||||||||

| Catalan: | perfectly | good | sufficient | very little | |||||||||||

| b. ¿Qué nivel de comprensión lectora tienes en cada una de estas lenguas? (What level of reading comprehension do you have in each of these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| c. ¿Qué fluidez tienes en cada una de estas lenguas? (How fluent are you in each of these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| d. ¿Cómo es tu pronunciación en cada una de estas lenguas? (How is your pronunciation in each of these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| e. ¿Cómo escribes en cada una de estas lenguas? (How do you write in each of these languages?) | |||||||||||||||

| In response to the following questions (1–4), indicate the frequency of use of Catalan and Spanish at different ages and in the different situations proposed. To do this, use the following scale and circle the corresponding option: | |||||||||||||||

| 1 = Sólo catalán—Only Catalan | |||||||||||||||

| 2 = Fundamentalmente catalán—Mainly Catalan | |||||||||||||||

| 3 = Más catalán que castellano—More Catalan than Spanish | |||||||||||||||

| 4 = Más castellano que catalán—More Spanish than Catalan | |||||||||||||||

| 5 = Fundamentalmente castellano—Mainly Spanish | |||||||||||||||

| 6 = Sólo castellano—Only Spanish | |||||||||||||||

| 14. ¿Siendo un niño pequeño, antes de iniciar la etapa escolar? (Being a small child, before starting the school stage?) | |||||||||||||||

| Sólo catalán—Only Catalan | Sólo castellano—Only Spanish | ||||||||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 | |||||||||||||||

| 15. ¿Siendo un niño, en la etapa de la educación primaria? (Being a child, in the stage of primary education?) | |||||||||||||||

| EN LA ESCUELA—At school | |||||||||||||||

| Sólo catalán—Only Catalan | Sólo castellano—Only Spanish | ||||||||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 | |||||||||||||||

| EN CASA—At home | |||||||||||||||

| EN OTROS LUGARES—Other places | |||||||||||||||

| 16. ¿En la pubertad, en la etapa de la educación secundaria y el bachillerato? (At puberty, at the stage of secondary education and high school?) | |||||||||||||||

| EN LA ESCUELA—At school | |||||||||||||||

| EN CASA—At home | |||||||||||||||

| EN OTROS LUGARES—Other places | |||||||||||||||

| 17. ¿En la edad adulta? (In adulthood?) | |||||||||||||||

| EN LA UNIVERSIDAD O EN EL TRABAJO—At University or at work | |||||||||||||||

| EN CASA—At home | |||||||||||||||

| EN OTROS LUGARES—Other places | |||||||||||||||

| 18. ¿En qué lengua te sientes más cómodo/a? (In which language do you feel most comfortable?) | |||||||||||||||

| English | Spanish | Catalan | In all three languages equally | ||||||||||||

| 19. ¿Percibes diferencias dialectales? (Do you perceive dialectal differences?) | |||||||||||||||

| In Catalan | |||||||||||||||

| No | Only between some dialects | Yes | |||||||||||||

| In Spanish | |||||||||||||||

| No | Only between some dialects | Yes | |||||||||||||

| 1 | The assessment of access to the non-standard Catalan variety and exposure was not directly conducted via a questionnaire, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer. However, our confidence in the knowledge and usage of this variety by our bilingual speakers stems from our extensive understanding of the Catalan context and its linguistic nuances, as well as from recent findings by Benito (2023). Moreover, a recent study by Pineda (2023) further supports the prevalence of this phenomenon across all Catalan dialects, involving approximately 400 speakers. This study used individual interviews and two tasks, namely sentence production and grammaticality judgments, demonstrating that the use of ‘a’ with animate (non-)definite objects is widespread across dialects. |

| 2 | We also conducted parallel statistical analyses that included Group as a between-subject fixed factor. However, no significant results involving Group (either alone or in interaction) emerged from this comprehensive analysis. Moreover, the effects of other factors within this overarching analysis appeared blurred or seemed annihilated, resulting in the emergence of perplexing patterns. In contrast, conducting separate analyses to examine each subpopulation individually revealed clearer patterns within each group. |

| 3 | A note regarding the use of raw RTs instead of residual RTs is needed. We calculated residual readings times (adopting Trueswell and Tanenhaus’s 1994 transformation procedure). We conducted analyses with both raw and residual RTs and the patterns of significance were parallel in both analyses. In this situation it is usual to report only one set of analyses (Keating and Jegerski 2015, p. 22). Therefore, we present results with raw RT data, as they are clearer. |

| 4 | Albeit our sentence items regarding this condition were linguistically ambiguous, as explained in relation to example (9b) above, they were not truly ambiguous for our participants since they widely selected the interpretation compatible with the subject RC. Our interpretation for this lack of ambiguity in interpretation is just that the easier subject RC strategy and the absence of DOM (DOM is optional in Spanish with animal objects) interfere in interpretation giving rise to the preferential reading attested. |

| 5 | As mentioned earlier in this text, we cannot specifically address Putnam et al.’s (2018) proposal that CLI predominantly flows from the dominant language to the non-dominant one since ou study focuses solely on a group of balanced bilingual speakers. Recently Benito (2023) has conducted a bidirectional study with more than a hundred of Catalan–Spanish bilinguals, from a similar origen to the participants in our current research, but with different degrees of language dominance covering a spectrum of bilingualism with varying degrees of relative language dominance, as measured by the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP, Birdsong et al. 2012). The analysis of DOM acceptability and production in Catalan reveals that CLI is indeed modulated by language dominance. Specifically, the stronger a bilingual’s dominance in Spanish, the greater the influence of Spanish on Catalan DOM. While there is observable influence from Catalan in bilingual Spanish, it is not as evident in the opposite direction (specially in acceptability), indicating an asymmetry in directionality. The lack of opposite bidirectional effects partially aligns with the predictions derived from Putnam et al. (2018), suggesting that factors beyond language dominance also play a role in explaining the source of CLI. |

References

- Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 435–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, Aurora, and Estela García-Alcaraz. 2018. Pronoun interpretation and processing in Catalan and Spanish bilingual and monolingual speakers. In Language Acquisition and Contact in the Iberian Peninsula. Edited by Alejandro Cuza and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. Boston and Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Rut. 2023. L’estabilitat referencial i la dominança lingüística en el marcatge diferencial d’objecte en el bilingüisme català-espanyol. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Betancort, Moisés. 2006. El procesamiento de oraciones de relativo de sujeto vs. objeto en español. Cognitiva 18: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancort, Moisés, Manuel Carreiras, and Patrick Sturt. 2009. The processing of subject and object relative clauses in Spanish: An eye-tracking study. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 62: 1915–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2008. Cognitive Control and Le Access in Younger and Older Bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning Memory and Cognition 34: 859–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Boix, Emili, and Cristina Sanz. 2008. Language & Identity in Catalonia. In Language & Identity. Edited by Jason Rothman and Mercedes Nino-Murcia. Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in Romance and beyond. New Analyses in Romance Linguistics 69: 143–70. [Google Scholar]

- Casado, Pilar, Carlos Fernández Frías, Manuel Martin-Loeches, and Francisco Muñoz. 2005. Are semantic and syntactic cues inducing the same processes in the identification of word order? Cognitive Brain Research 24: 526–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeaux, Ian, and Janet L. McDonald. 2018. Determining the Effectiveness of Visual Input Enhancement Across Multiple Linguistic Cues. Language Learning: A Journal of Research in Language Studies 68: 5–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Albert, Mikel Santesteban, and Irina Ivanova. 2006. How do highly proficient bilinguals control their lexicalization process? Inhibitory and language-specific selection mechanisms are both functional. Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning Memory and Cognition 32: 1057–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, Mary, and Irina Nikolaeva. 2011. Objects and Information Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, James. 2012. Phonetic interference of Catalan in Barcelonan Spanish: A Sociolinguistic approach to lateral velarization. In Selected Proceedings of the 14th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Kimberly Geeslin and Manuel Díaz-Campos. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 319–39. [Google Scholar]

- Del Río, David, Ramón López-Higes, and María Teresa Martín-Aragoneses. 2012. Canonical word order and interference-based integration costs during sentence comprehension: The case of Spanish subject- and object-relative clauses. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 5: 2108–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2013. Differential Object Marking in Spanish: State of the art. Borealis: An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 2: 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Lynn. 1987. Sentence processing: A tutorial review. In Attention and Performance 12: The Psychology of Reading. Edited by Max Coltheart. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., pp. 559–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gavarró, Anna, Arnau Cunill, Míriam Muntané, and Marc Reguant. 2012. The acquisition of Catalan relatives: Structure and processing. Revue Roumaine Linguistique/Romanian Rev. Linguist 57: 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro-Fuentes, Pedro. 2012. The acquisition of interpretable features in L2 Spanish: Personal “a”. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 701–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roger. 1989. Do second language learners acquire restrictive relative clauses on the basis of relational or configurational information? The acquisition of French subject, direct object and genitive restrictive relative clauses by second language learners. Second Language Research 5: 156–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Nick, Carrie N. Jackson, and Holger Hopp. 2020. Cue coalitions and additivity in predictive processing: The interaction between case and prosody in L2 German. Second Language Research 38: 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Virginia M., and J. Kevin O’Regan. 1981. Eye fixation patterns during the reading of relative-clause sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 20: 417–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, Holger. 2006. Syntactic features and reanalysis in near-native processing. Second Language Research 22: 369–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, Holger, and Mayra E. León Arriaga. 2016. Structural and inherent case in the non-native processing of Spanish: Constraints on inflectional variability. Second Language Research 32: 75–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Natascha Müller. 2000. Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut d’Estudis Catalans. 2016. Gramàtica de la llengua catalana. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, Shinichi. 2003. Processing Difficulty in Comprehension and Production of Relative Clauses by Learners of English as a Second Language. Language Learning 53: 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, Scott, and Aneta Pavlenko. 2008. Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jegerski, Jill. 2015. The processing of case in near-native Spanish. Second Language Research 31: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, Marcel A., and Patricia A. Carpenter. 1980. A Theory of Reading. From Eye Fixations to Comprehension. Psychological Review 87: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, Gregory, and Jill Jegerski. 2015. Experimental designs in Sentence processing Research. A methodological review and user’s guide. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 37: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Jonathan, and Marcel A. Just. 1991. Individual differences in syntactic processing: The role of working memory. Journal of Memory and Language 30: 580–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laca, Brenda. 2006. El objeto directo. La marca preposicional. In Sintaxis historica de la lengua espanola. Primera parte: La frase verbal. Edited by Concepción Company Company. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, pp. 423–75. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana. M. 1986. Linguistic Theory and Second Language Acquisition: The Spanish Nonnative Grammar of English Speakers. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- López, Luis. 2012. Indefinite Objects: Scrambling, Choice Functions and Differential Object Marking. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, Pim, Wietske Vonk, and Herbert Schriefers. 2006. Animacy in processing relative clauses: The hikers that rocks crush. Journal of Memory and Language 54: 466–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, and C. M. Fausey. 2006. Language-Dependent Memory in Bilingual Learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology 20: 1025–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Viorica, Henrike K. Blumenfeld, and Margarita Kaushanskaya. 2007. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 50: 940–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, Jürgen. M. 2021. Diversity and divergence in bilingual acquisition. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 40: 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsugi, Sanako, and Brian MacWhinney. 2015. The use of case marking for predictive processing in second language Japanese. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Melanie Bowles. 2009. Back to basics: Incomplete knowledge of differential object marking in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12: 363–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina, Rakesh Bhatt, and Roxana Girju. 2015. Differential object marking in Spanish, Hindi and Romanian as heritage languages. Language 91: 564–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolieri, Daniela, Josep Demestre, Marc Guasch, and Teresa Bajo. 2020. The gender congruency effect in Catalan–Spanish bilinguals: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23: 1045–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiñán, Sílvia. 2018. On Convergence, Ongoing Language Change and Crosslinguistic Influence in Direct Object Expression in Catalan–Spanish Bilingualism. Languages 3: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiñán, Sílvia, and Adriana Soto-Corominas. 2021. Indirect Stuctural Crosslinguistic Influence in early Catalan-Spanish Bilinguals in Adulthood. Predicate Selection in Catalan Existential Constructions. Language Acquisition 42: 1463–502. [Google Scholar]

- Perpiñán, Sílvia, and Itziri Moreno Villamar. 2013. Inversion and case assignment in the language of Spanish heritage speakers. Paper presented at 2013 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistics Association, Victoria, BC, Canada, June 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Anna. 2023. L’acusatiu preposicional en català: D’on venim i cap a on anem? Caplletra Revista Internacional de Filologia 74: 149–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Mayenco, Eloi, Ian Cunnings, Fatih Bayram, David Miller, Susagna Tubau, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Language Dominance Affects Bilingual Performance and Processing Outcomes in Adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, Michael T., and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition? A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 478–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael T., Tanja Kupisch, David Miller, Fatih Bayram, Jason Rothman, and Ludovica Serratrice. 2018. Different situations, similar outcomes. In Bilingual Cognition and Language. The State of the Science across Its Subfields. Edited by David Miller, Ludovica Serratrice, Jason Rothman and Fatih Bayram. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 251–80. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. 2010. Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Sagarra, Nuria, Aurora Bel, and Liliana Sánchez. 2020. Animacy hierarchy effects on L2 processing of Differential Object Marking. In The Acquisition of Differential Object Marking. Edited by Alexandru Mardale and Silvina Montrul. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sagarra, Nuria, Liliana Sánchez, and Aurora Bel. 2017. Processing DOM in relative clauses. Salience and optionality in early and late bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 9: 120–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2014. Bilingual Language Acquisition: Spanish and English in the First Six Years. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2016. Referring expressions and executive functions in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 6: 669–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thane, Patrick D. 2024a. Acquiring differential object marking in heritage Spanish: Late childhood to adulthood. International Journal of Bilingualism. First published online February 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thane, Patrick D. 2024b. On the Acquisition of Differential Object Marking in Child Heritage Spanish: Bilingual Education, Exposure, and Age Effects. Languages 9: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrego, Esther. 1998. The Dependencies of Objects. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traxler, Matthew J., Robin K. Morris, and Rachel E. Seely. 2002. Processing subject and object relative clauses: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Memory and Language 47: 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoza, Natalia. 2016. Impacto del orden canónico de constituyentes y la animacidad en el procesamiento de oraciones en español. Master’s thesis, Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU), Vitoria/Gasteiz, Spain. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset age of exposure to oral Catalan (mean in years) | 0.45 | 0.99 |

| Onset age of exposure to oral Spanish (mean in years) | 2.89 | 2.10 |

| Self-reported Catalan level (out of 4) | 3.99 | 0.06 |

| Self-reported Spanish level (out of 4) | 3.98 | 0.06 |

| Average daily use of Catalan in childhood (out of 6) * | 4.57 | 0.99 |

| Average daily use of Catalan in puberty (out of 6) * | 4.44 | 1.02 |

| Average daily use of Catalan in adulthood (out of 6) * | 4.35 | 0.95 |

| Subject RC (SVO) | Object RC (OVS) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Postverbal Noun (Object) Obligatory DOM (e.g., La gorila que abrazó a la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Object) Optional DOM (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó a la gorila…) | Human Postverbal Noun (Subject) (e.g., La gorila que abrazó la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Subject/Object) (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó la gorila…) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Monolinguals | 87.5 | 33.6 | 97.37 | 16.22 | 73.7 | 46.54 | 18.92 | 39.71 |

| Bilinguals | 93.75 | 24.59 | 89.47 | 31.1 | 54.55 | 50.56 | 10.81 | 31.48 |

| F | df1 | df2 | p | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolinguals | Type of RC | 42.618 | 1 | 136 | <0.001 | 0.742 |

| DOM | 1.232 | 1 | 136 | 0.269 | 0.020 | |

| Type RC × DOM | 15.022 | 1 | 136 | <0.001 | 0.207 | |

| Bilinguals | Type of RC | 46.504 | 1 | 136 | <0.001 | 0.820 |

| DOM | 8.115 | 1 | 136 | 0.005 | 0.140 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 3.477 | 1 | 136 | 0.064 | 0.060 |

| Region | Subject RC (SVO) | Object RC (OVS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Postverbal Noun (Object) Obligatory DOM (e.g., La gorila que abrazó a la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Object) Optional DOM (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó a la gorila…) | Human Postverbal Noun (Subject) (e.g., La gorila que abrazó la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Subject/Object) (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó la gorila…) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Last N RC ‘bióloga/gorila’ | 524 | 289 | 566 | 523 | 735 | 694 | 595 | 653 |

| Verb ‘sonreía’ | 555 | 346 | 517 | 263 | 657 | 401 | 529 | 241 |

| Adverb ‘incesantemente’ | 851 | 615 | 969 | 640 | 873 | 534 | 833 | 608 |

| Region | F | df1 | df2 | p | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Last N RC | Type of RC | 6.508 | 1 | 283 | 0.011 | 0.250 |

| DOM | 14.602 | 1 | 283 | <0.001 | 0.563 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 1.868 | 1 | 283 | 0.173 | 0.068 | |

| Verb | Type of RC | 3.154 | 1 | 278 | 0.077 | 0.498 |

| DOM | 3.161 | 1 | 278 | 0.077 | 0.499 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 0.356 | 1 | 278 | 0.551 | 0.056 | |

| Adverb | Type of RC | 0.079 | 1 | 277 | 0.779 | 0.015 |

| DOM | 2.891 | 1 | 277 | 0.090 | 0.446 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 1.670 | 1 | 277 | 0.197 | 0.256 |

| Region | Subject RC (SVO) | Object RC (OVS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Postverbal Noun (Object) Obligatory DOM (e.g., La gorila que abrazó a la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Object) Optional DOM (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó a la gorila…) | Human Postverbal Noun (Subject) (e.g., La gorila que abrazó la bióloga…) | Animal Postverbal Noun (Subject/Object) (e.g., La bióloga que abrazó la gorila…) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Last N RC ‘bióloga/gorila’ | 538 | 373 | 500 | 255 | 699 | 775 | 522 | 422 |

| Verb ‘sonreía’ | 527 | 297 | 485 | 231 | 545 | 274 | 479. | 239 |

| Adverb ‘incesantemente’ | 812 | 696 | 856 | 705 | 1021 | 950 | 826 | 637 |

| Region | F | df1 | df2 | p | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Last N RC | Type of RC | 0.213 | 1 | 285 | 0.645 | 0.013 |

| DOM | 3.491 | 1 | 285 | 0.063 | 0.213 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 14.458 | 1 | 285 | <0.001 | 0.674 | |

| Verb | Type of RC | 0.076 | 1 | 282 | 0.783 | 0.014 |

| DOM | 5.443 | 1 | 282 | 0.020 | 0.445 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 0.024 | 1 | 282 | 0.877 | 0.001 | |

| Adverb | Type of RC | 4.892 | 1 | 283 | 0.028 | 0.726 |

| DOM | 0.277 | 1 | 283 | 0.599 | 0.045 | |

| Type of RC × DOM | 1.740 | 1 | 283 | 0.188 | 0.229 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bel, A.; Benito, R. Differential Object Marking in Structurally Complex Contexts in Spanish: Evidence from Bilingual and Monolingual Processing. Languages 2024, 9, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060211

Bel A, Benito R. Differential Object Marking in Structurally Complex Contexts in Spanish: Evidence from Bilingual and Monolingual Processing. Languages. 2024; 9(6):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060211

Chicago/Turabian StyleBel, Aurora, and Rut Benito. 2024. "Differential Object Marking in Structurally Complex Contexts in Spanish: Evidence from Bilingual and Monolingual Processing" Languages 9, no. 6: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060211

APA StyleBel, A., & Benito, R. (2024). Differential Object Marking in Structurally Complex Contexts in Spanish: Evidence from Bilingual and Monolingual Processing. Languages, 9(6), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9060211