Abstract

This study focuses on accent shift or stylization to American English features in Anglophone pop-rock music and examines linguistic constraints alongside music-related considerations, as well as the effect of changes in musical genre on variable accent shift. The case study is the British band Mumford and Sons and their variable production of non-prevocalic rhotics as either present or absent. Mumford and Sons is of interest because they have displayed a change in their musical style throughout their career from Americana to alt-rock. The band’s four studio albums were auditorily analyzed and coded for rhotic vs. non-rhotic with aid from spectrograms. The linguistic factors considered were word class, preceding vowel according to the word’s lexical set, complexity of the preceding vowel, syllable complexity, stress, and location within the word and phrase. In addition, the effect of singing-related factors of syllable elongation and rhyming, and of the specific album, were also explored. Results show that rhoticity is favored in content words, stressed contexts, complex syllables, and NURSE words. This pattern is explained as stemming from the perceptual prominence of those contexts based on their acoustic and phonological characteristics. Results further show that syllable elongation leads to more rhoticity and that rhyming words tend to agree in their (non-)rhoticity. Finally, the degree of rhoticity decreases as the band departs from Americana in their later albums, highlighting the relevance of music genre for accent stylization.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of British pop-rock music performers displaying a Mid-Atlantic accent that includes American English features when singing and conflicts with their spoken dialect has been present since the inception of this music style (Trudgill 1983). While the degree of accent shift among British singers has changed throughout time (Simpson 1999; Carlsson 2001), the presence of American English features can still be heard among many contemporary performers from the UK and in Anglophone pop-rock more generally. In the sociolinguistic literature, this type of accent shift or accent stylization has been discussed within theories of dialect imitation and referring to indices of place, i.e., artists wanting to sound American (Trudgill 1983; Simpson 1999). More recent studies, however, argue that the American English accent has become mainstream and the default or expected register, rather than a locality index, in pop-rock performances, and singers that depart from it are implementing an effort to break away from those expectations (Beal 2009; Gibson and Bell 2012; Jansen 2018). Commercial considerations in terms of audience markets have also been taken into account to explain the Mid-Atlantic accent shift (O’Hanlon 2006; Schulze 2014; Flanagan 2019). However, the role of musical styles or genres within pop-rock music in accent stylization has not been thoroughly explored, despite some research on accent shift and genres in relation to hip hop and country music (Duncan 2017; Gibson 2023). Building off this work, this study examines a case study of accent stylization where a band displays a genre transition in their career from Americana or folk-rock to alt-rock.

The Mid-Atlantic accent shift has been characterized as variable rather than categorical or complete, and several authors have hypothesized that these inconsistencies might arise from competing identities that are associated with other accents that performers possess or want to index (Trudgill 1983; Jansen and Westphal 2017). However, when discussing variation in accent stylization, the relevance of linguistic constraints has not been addressed in detail (Morrissey 2008; Gibson 2010), even though these factors might be conditioning the outcome of accent shift, as they do in other instances of linguistic variation. Consequently, to fill in this gap, this study explores accent stylization in singing as a variable feature and examines linguistic factors that might condition it to identify patterns in the variable production of stylized features and bring a new perspective to the idea of not “hitting the mark” or not fully adopting a given feature. Furthermore, the mode of singing is taken into account by considering factors that are unique to musical performances and might govern linguistic choices in sung vs. spoken speech beyond sociolinguistic considerations (Morrissey 2008).

The case study comes from the British band Mumford and Sons’ musical and performance practices and their variable production of non-prevocalic rhotics as either present or absent, which reflects the difference between r-ful and r-less dialects of English. Mumford and Sons’ singer’s spoken accent falls within Southern British English, which is r-less and presents non-rhoticity in non-prevocalic positions, which contrasts with the rhoticity of General American English (Wells 1982). Mumford and Sons provide an interesting case of a band that displays a change in their musical style throughout their career, from Americana or folk-rock to alt-rock, and allows us to explore the impact of this on their accent stylization. The focus is on non-prevocalic rhoticity because this feature has been described as a stereotype of American English (Gibson 2023) and, of all Mid-Atlantic features, it lends itself best to auditory analysis and allows for comparison with the sound change in non-rhotic dialects of English becoming rhotic. Through a quantitative analysis of rhoticity in Mumford and Sons’ discography, we address our two goals: (i) to examine linguistic constraints alongside music-related considerations on the variation displayed in accent shift, and (ii) to explore the effect of changes in musical style or genre on accent shift. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides background to key aspects related to accent stylization in Anglophone pop-rock music with a focus on British performers and the band under study. Section 3 details the methods, and Section 4 summarizes the results of the quantitative study. Section 5 discusses the main findings, and Section 6 presents the main conclusions and suggests avenues for further research.

2. Background

2.1. Stylization in Popular Music: Style Shift in Anglophone Pop-Rock

While both singing and spoken speech can be seen as performative in nature and to form a continuum (Gibson 2023), singing is a type of staged performance that oftentimes leads to differences with spoken speech. One notable case comes from popular music artists whose singing accent includes pronunciation features that are absent from their spoken or vernacular dialect. This type of accent shift in music has been described as a case of register or style shift that leads to stylization in singing voices (Simpson 1999; Morrissey 2008; Bell and Gibson 2011) and has been identified in many languages (e.g., Yaeger-Dror (1991) for Hebrew, Lin and Chan (2022) for Mandarin Chinese, Fernández De Molina Ortés (2023) and Hayes (2023) for Spanish, Owens (2023) for French). Within Anglophone pop-rock, the stylization of non-American singers who display American English features in their singing has been examined for British, New Zealand, and Australian performers. Simpson (1999) proposes the USA-5 model to encapsulate the features that singers might display: flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ (e.g., in city); [⸪] for the BATH1 vowel (e.g., in can’t); monophthongization of the PRICE vowel (e.g., in mine); non-prevocalic rhoticity (e.g., in car park); and unrounded LOT vowel (e.g., in body). These features are considered stereotypes of American English and, while some of them might be found in non-American dialects, there is no single such variety that includes all of them (Simpson 1999). The Mid-Atlantic accent, the focus of study here, displays British as well as USA-5 model features. While Simpson’s model has been widely adopted in studies of Anglophone pop-rock, some authors have examined other sounds that distinguish American and other English dialects (e.g., Gibson and Bell 2012), and Gibson (2023) proposes the term Pop Song English to refer to the register employed by many popular music performers that incorporates American English characteristics.

Accent stylization in singing is complex and multidimensional, and it might be explained by several factors, including conflicting motivations (Simpson 1999; Bell and Gibson 2011). Earlier accounts of stylization in British pop-rock refer to place indexicalities, where place is geographically defined, and artists wanting to identify as American. Trudgill (1983), in his seminal study, adopts Le Page’s work on linguistic imitation in his analysis of British bands through the 1960s and 1970s and argues that singers imitate the model group with which they want to identify, i.e., Americans. This desire comes from the domination of the field of pop-rock music by Americans (at least back then) and the genre’s roots in the US (Trudgill 1983). However, Trudgill notes that as British pop-rock became more established on the global music stage, artists displayed a decrease in their use of American features, which culminated with the (almost) entire abandonment of the USA-5 model by British punk performers in the 1970s. This pattern comes out of his quantitative description of the use of several American features, including rhoticity, by British artists, which provides a point of comparison for later studies, including the current one. Trudgill’s work also addresses constraints on the degree of imitation, following Le Page’s model, and highlights the conflicting motivations towards the desired model and towards retaining one’s identity which result in what he calls “acts of conflicting identity” (Trudgill 1983).

Simpson (1999) expands Trudgill’s work theoretically and by looking at later British pop-rock bands in the 1980s and 1990s. Simpson, while maintaining place references for accent features, understands dialect shift as an instance of register shift, which motivates him to consider issues related to discourse in relation to dialect stylization in singing, i.e., tenor, field, and mode. Among these, tenor and field are relevant when analyzing linguistic practices in singing because they are specific to each artist. Tenor in music performances, according to Simpson, is not defined by the speech style of an addressee but rather by Coupland’s “projected social role or persona” (Coupland 1988, p. 139), which might change over an artist’s career and be reflected in their stylization. Like Trudgill, Simpson emphasizes the importance of considering conflicting motivations when analyzing dialect shift in singing and changes in the weight of those motivations through an artist’s career. Simpson concludes that the American model has lost relevance in British pop-rock (see also Carlsson 2001), although some features remain among British bands, which he refers to as “epiphenomena” (Simpson 1999, p. 363).

However, recent studies claim that using the USA-5 model does not signal a locality or identity but rather mainstream pop-rock, arguing that this type of stylization has become the norm, i.e., the default style (Beal 2009; Gibson and Bell 2012; Jansen 2018; Flanagan 2019; Westphal and Jansen 2021). Beal (2009) provides a qualitative analysis of the early albums of the indie British band Arctic Monkeys framed within a language-ideological approach (Silverstein 1976) and the concepts of indexicalities and enregisterment, the process by which linguistic features become associated with certain social categories and imbued with social meaning (Agha 2003). Beal reports an absence of USA-5 features in the albums she analyzes but a notable presence of features associated with the band’s local Sheffield accent, which mirrors the spoken speech of the singer. Beal argues that Arctic Monkeys use certain local features to index their status as Northerners and as young, concluding that in British popular music, “regional pronunciations index authenticity and independence” (Beal 2009, p. 238), while the USA-5 features index adherence to mainstream pop-rock. This suggests that the indexicalities of local vernacular features in pop-rock music are formed in opposition to those of the USA-5 model and display covert prestige (Trudgill 1983), which is different from those same features in spoken speech. Flanagan (2019) builds off Beal’s work to analyze the Arctic Monkeys’ career and finds changes in the degree of use of USA-5 and regional features, with the latter displaying a sharp decrease in later albums while slightly picking up in their last record. Like Beal, Flanagan connects American features with a closer proximity to the music industry, but his work highlights how artists’ stylization is dynamic and can diachronically change reflecting new or competing motivations, something that informs the current study’s analysis of Mumford and Sons’ discography. The status of an American accent as the default in pop-rock music has also been found for audience’s perceptions. Jansen (2018) evaluates the attitudes of British listeners towards American English in general and British music in particular and finds that, while overall the attitudes in music are negative, participants demonstrate a degree of expecting American English in singing, especially in pop music. Jansen (2018) concludes that Americanized singing functions as the default, without any act of identity, and it indexes mainstream and certain genres.

Accent stylization in music, especially the dichotomy between singing in the default accent vs. the vernacular, has been conceptualized within the Aaudience Ddesign model (Bell 1984, 2001; Bell and Gibson 2011; Gibson and Bell 2012; Morrissey 2008). Morrissey (2008) refers to the American features used by artists as the reference style in pop-rock singing and argues that British performers display outgroup referee design when they adopt the USA-5 model. However, the use of local or vernacular features is a form of ingroup referee design. Note how the audience in singing does not play the role that is most common in spoken speech, something that sets these two modes apart (Morrissey 2008). Another important differentiation within this model is that between responsive and initiative style shifts (Bell 2001). A responsive shift is predictable given the situation and interlocutors, adopting an expected style that is appropriate for the context. On the other hand, an initiative shift occurs when there is a change in style that alters the situation or the roles of the interlocutors and involves using an unexpected style that disrupts the convention. Gibson and Bell (2012) apply these two concepts to their findings from a study of the singing pronunciation practices and attitudes of three New Zealand (NZ) pop-rock musicians. The authors conclude that the Americanized accent functions as the default style used in pop singing, and the use of NZ features requires “effort and an initiative act of identity” (Gibson and Bell 2012). Thus, they theorize that the use of American English features in singing is a responsive style shift for the performers they analyze, while the use of local ones involves an initiative style shift (see also Gibson 2023). However, the situation among British pop-rock singers might be more complex, as some studies have found a move away from the USA-5 model and a shift to some kind of standard Southern British English (SBE) with resemblances to RP, where regional features are less present (Simpson 1999; Carlsson 2001).

This interplay between local and standard features can be seen through the lens of glocalization, which, in this context, refers to bringing local elements to the global music stage, and vice versa. Glocalization has been extensively explored for hip hop artists (Pennycook 2007; Alim 2009; Williams 2017), but it can also be applied to pop-rock, as Schulze (2014) shows in their analysis of several British rock and indie bands. Glocalization brings to the forefront matters related to mainstream success, financial considerations and audience markets, all factors that have not received as much attention in relation to American stylization in pop-rock (although see O’Hanlon 2006; Schulze 2014; Flanagan 2019) but highlight the performative nature of commercial music performances and recordings. This nature brings us to the role of music genre in singing stylization, something that is important for the goals of the current study.

Several of the studies discussed so far have alluded to the importance of genre in singing linguistic practices, or what Hayes (2023) calls artistic performance speech, yet others have taken this relevance as the core of their approach. Music genre should be understood as an orientation, rather than a clearly defined classification (Coupland 2011; Schulze 2014), that usually comes with a set of organizing elements (musical, instrumental, linguistic, visual, etc.) that musicians incorporate into their performance and that are expected by the audience, although genre boundaries might be porous and hard to establish. Coupland (2011) centers singing as performance and highlights the role of genre in stylization, arguing that place indexicalities are mediated through genre. For the author, place in music is not a geographical location but instead a sociocultural context that is dependent upon genre expectations. Coupland presents three case studies from classic rock and roll, folk/country, and punk rock to show how place meanings are subordinated to some extent to the defining elements of each genre; more precisely, certain linguistic practices might acquire different meanings depending on the music genre of the performance. Other studies, focusing on accent shift, have compared the adoption of American features by performers from different genres. O’Hanlon (2006) analyzes the use of USA-5 by Australian hip hop performers and performers of other youth genres, including rock, pop, alternative, and punk music. Results from the quantitative analysis show that the American model is seen only occasionally among hip hop artists, while in the other genres, the model is more present, albeit inconsistent, with the highest rate of use in pop songs. O’Hanlon’s findings are evidence for the role of genre in linguistic stylization. Gibson (2023) further explores genre differences in two of the USA-5 features, rhoticity and the BATH vowel, but in this case in New Zealand (NZ) performers. Through a corpus analysis of NZ and US pop and hip hop artists, the author finds that nearly all NZ artists display the two features to some degree, with a greater rate for pop than hip hop performers, the latter preserving their local pronunciations more frequently. In fact, NZ pop singers use the two features at similar rates to their US counterparts. Gibson concludes that these findings correlate with a less dramatic style shift away from their spoken accent for hip hop than pop artists.

When considering the role of musical genre in stylization, the concept of authenticity is relevant, as Duncan (2017) shows in his study of accent shift in country music. The author explores the use of three features of Southern American English by the Australian country singer, Keith Urban, as he shifts to this dialect in his performances: rhoticity, alveolarization of -ing forms, and PRICE monophthongization. Duncan (2017) examines Urban’s singing and spoken speech and compares him to three country singers from the US. Results from the quantitative analysis indicate that Keith Urban produces the three features under study in a similar fashion to the American performers in his singing but not in his speech. Interestingly, US artists present some accent shifting as well, but to a much lesser degree than Urban. Duncan argues that Urban shifts his style to include Southern American English features to present himself as an authentic country musician. As an Australian performer, Urban lacks other indices of authenticity that US singers might have, such as their personal background, so he employs the index available to him: accent. In Duncan’s theorizing, an authentic performance is one that includes the features that are enregistered as such for the given genre, i.e., that show authentic cultural membership. From this follows that genre determines how artists “perform authenticity” (Duncan 2017). This is echoed in other studies that mention that what counts as authentic varies from genre to genre (Coupland 2011; Schulze 2014, and see previous paragraph).2 The current project will take a closer look at the impact of genre on the stylization of British performers by tracing the development of the phenomenon as the band under study undergoes a change in their music style.

Apart from matters related to genre, the performative nature of singing requires us to consider music-related constraints that might condition style shifting and go beyond the social factors that might affect such stylization. While several studies acknowledge the importance of musical restrictions (e.g., Beal 2009; Coupland 2011; Gibson 2023), only a few consider them in any detail. Morrissey (2008) focuses on sonority as a characteristic that determines the singability of any given sound. He defines sonority as the degree of constriction in the oral cavity during the production of a sound, with more sonorous sounds being articulated with less constriction, through which the air can flow less unimpeded. Thus, according to Morrissey, high-sonority sounds allow the singer to “carry the tune” better than low-sonority ones and allow for the voice to stand out against the instruments (Morrissey 2008, p. 210). Applying this to the USA-5 model, Morrissey argues that the American features are more sonorous that their RP and SBE counterparts, and this might make them preferred in singing voices. For example, the more open vowels characteristic of the American style are more sonorous than RP’s more closed ones. Of interest to the current study, Morrissey applies his sonority model to rhoticity and predicts that non-rhoticity might be preferred, especially in sustained notes, because the presence of a rhotic brings a degree of constriction that its absence does not entail. This is something that will be explored in the quantitative analysis reported below. Building off Morrissey (2008), Konert-Panek (2017) argues that British singer Amy Winehouse’s stylization to American features might be in certain specific cases conditioned by the sonority of those sounds when compared with the singers’ local Cockney ones, which are characterized by more constriction, i.e., less sonority. Given the limited focus on musical restrictions on stylization in previous research, our study takes two such factors into consideration, namely the elongation of syllables for sustained notes and rhyming.

The main drive for this project is something that should be clear from the discussion so far: stylization to the USA-5 model in Anglophone pop-rock is a variable phenomenon. Previous authors refer to the fact that the outcome of this stylization is not categorical but rather presents inconsistencies (see papers cited above), and the Mid-Atlantic accent has been referred to as a hybrid accent (Trudgill 1983). Bell and Gibson (2011) list four sociophonetic processes that are at play in singing stylization and that result in variability: selectivity in terms of what features are adopted, mis-realizations of those features, overshoot of adopted features to unexpected degrees, and undershoot of the features in expected contexts. Previous work explains this variability by considering sociolinguistic factors, including competing motivations, as explained earlier, but there is a sense that some of the variability is not constrained by social considerations. This study aims to shed light on this by exploring the role of linguistic factors on variation in stylization. Together with musical constraints, these factors have not been given much attention in the literature, but here it is argued that exploring them will allow us to get a different perspective on the phenomenon. The next section provides some background and motivates the focus on the band Mumford and Sons and the feature of variable rhoticity in singing.

2.2. Rhoticity and Mumford and Sons

This study examines one of the USA-5 model features: rhoticity. The term rhoticity refers to the production of non-prevocalic coda rhotics, e.g., in words like heart or car park. This feature distinguishes rhotic and non-rhotic dialects of English (also referred to as r-ful and r-less, respectively). American dialects, including Standard or General American English, by and large show rhoticity, although there are varieties in the US that present non-rhoticity, most notably African American English, New England English, and Southern American English (Feagin 1990; Thomas 2007; Becker 2014). On the other hand, Southern British English, the dialect of interest for the band under study, is characterized as non-rhotic, although there are rhotic dialects in England such as West Country English and Lancashire English (Piercy 2012; Turton and Lennon 2023). Several studies on stylization in Anglophone pop-rock examine rhoticity as an important feature (Trudgill 1983; O’Hanlon 2006; Duncan 2017; Konert-Panek 2017; Gibson 2023), providing a point of comparison for our quantitative study. Gibson (2019, 2023) analyzes rhoticity in US and New Zealand pop singers and finds that US performers do not present rhoticity in all contexts where it would be expected, leading Gibson to conclude that the target American model for stylization is not fully rhotic but presents some variation (see also Duncan 2017).

Another consideration for focusing on rhoticity is related to methodological issues. It is very difficult to perform acoustic analysis in commercial music recordings since, due to production techniques, it is not possible to separate the vocal track from the instruments without considerably degrading the sound quality. For this reason, analysts have to examine the singing voice together with the music, which makes acoustic analysis virtually impossible. This leaves auditory analysis as the best technique for exploring stylization (O’Hanlon 2006). When considering the USA-5 features, while vowels are best analyzed acoustically according to sociophonetic studies, the presence or absence of rhoticity lends itself better to an auditory analysis since the differentiation is binary, especially compared to vowel production. Finally, Morrissey (2008) discusses rhoticity in relation to musical restrictions in stylization (see above) and presents predictions that can be tested, something that the current study pursues.

The band Mumford and Sons was formed in London in 2007 and has released four studio albums. The lead singer, Marcus Mumford, whose stylization is the focus of this study, while born to English parents in the US, grew up in southwest London from the age of 6 months. His spoken dialect is characteristic of that geographical location, and it is markedly non-rhotic. However, he displays style shift and incorporates American features in his singing voice, which has been described by a music critic as “bobbing about somewhere in the mid-Atlantic” (Petridis 2015). Mumford and Sons’ first two albums, Sigh No More (2009) and Babel (2012), broadly fall within the Americana music genre, although some music observers place them within folk-rock. Their last two albums, Wilder Mind (2015) and Delta (2018), however, present a change in their music to an alt-rock, indie rock, or classic rock style (Petridis 2015), resulting in a “defolking” of their music, as seen in, for example, the exclusion of the banjo from their instrumentation (Empire 2015). The alignment of their first two albums with the Americana genre can be seen in the Emerging Artist of the Year Award they received from the Americana Music Association in 2011 and the Trailblazer Award from the UK Americana Association in 2018.3 In addition, Babel was nominated for Best Americana Album at the 2013 Grammy Awards. In contrast, when the UK Americana chart was launched in 2016, Mumford and Sons were not included because they did not fit the criteria to be considered Americana at that point, which coincides with their third album (Sherwin 2016).

Americana is a term that began to be applied to music in the 1990s. The Americana Music Association (AMA) was founded in 1999, and the first AMA awards ceremony took place in 2002. The Recording Academy recognized Americana as its own genre in 2006 and established a Grammy award in that category in 2009. Americana is a genre-blending style that has been largely associated with folk and country music but more generally borrows elements from American-roots music (Cobbey 2023; Grammy Awards 2023). Oftentimes, musicians that are included in the Americana genre are also associated with country, folk, or rock. Music critics describe the elements that characterize Americana in terms of the instruments, which tend to be acoustic and include banjo, mandolin, and fiddles, and of the vocals, which incorporate the “twang” of country music but with “weathered” harmonies (Cobbey 2023). Coming back to Mumford and Sons, it is important to note that they perform their musical identity, aligning themselves with Americana, multi-modally, not just with accent indexicalities (Coupland 2011). In terms of voice, style shifting to American features is present, but they also bring harmonizations that seem to be indexical of this kind of folk-offshoot music genre, as mentioned earlier. In addition, Mumford and Sons incorporate elements in their appearance, including clothing, and in their selection of instruments that help build their identity within the genre. Thus, while here we focus on accent stylization, a more thorough analysis of how they build their identity as performers would need to take a multi-modal approach, which is not common among linguistic studies (but see Gibson 2011; Morini 2013; Schulze 2014) and goes beyond the scope of this study.

3. Materials and Methods

Mumford and Sons’ four studio albums to date were included in the analysis: Sigh No More (2009), Babel (2012), Wilder Mind (2015), and Delta (2018). The recorded version of every track from each album was analyzed, with the exception of Darkness Visible from Delta, where the only voice is that of Americana artist Gill Landry as he reads from Milton’s Paradise Lost. This resulted in a total of 49 songs, evenly split across each album, 12 per record, except for Delta, which had 13 analyzable tracks. The songs were extracted from CDs of the albums and converted into .wav files for the data analysis.

All instances of syllable final, non-prevocalic orthographic <r> were examined. Each token was coded as rhotic or non-rhotic based on auditory analysis with aid from spectrograms and waveforms in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2020). Rhoticity could be manifested as a rhotic consonant or /r/-coloring of the preceding vowel, i.e., a rhotacized vowel. Linking <r>, i.e., the production of word-final etymological <r> before a vowel-initial word (e.g., in car is blue), while present in the data, was not included in the analysis because this type of rhoticity is expected in the singer’s spoken speech and might not be a USA-5 feature. However, hyper-rhotics, i.e., rhotic productions that do not correspond with etymological <r>, were identified and noted in the analysis. Only singing by the lead singer was analyzed, and cases of harmonization with background vocals were not included. All repetitions of a word were explored, following Gibson and Bell (2012), since variation among repetitions was observed.

Tokens were coded for several linguistic factors that have been shown to affect variable phenomena in general and variable rhotic production in dialects of English in particular (Nagy and Irwin 2010; Blaxter et al. 2019; Gibson 2019). These factors include: word class of the lexical item containing the rhotic (function vs. content word); preceding vowel according to the word’s lexical set (Wells 1982); complexity of the preceding vowel (monophthong vs. diphthong); syllable complexity (simple, i.e., <r> as the only coda consonant vs. complex, i.e., <r> followed by another coda element, e.g., far vs. heart); stress (stressed vs. unstressed); following context (consonant vs. pause); location within the word (medial vs. final); and location within the phrase (medial vs. final). In addition, two singing-related factors were examined: elongation of the syllable to maintain a musical note (elongated vs. non-elongated syllables) and rhyming. Finally, the specific album was also coded to explore changes throughout the band’s career.

The effect of these factors, except for rhyming, on rhotic production (presence vs. absence of rhotic) was explored using mixed-effects binomial generalized linear regression with the glmer () function from the lme4 package in R (Bates et al. 2015). The interaction between word class and stress was also considered in the regression modeling based on descriptive statistics. Models were built stepwise and compared using ANOVA to determine the best-fit model. Word was included as a random effect in all models. In addition, the effect of rhyming on rhoticity and hyper-rhotics were examined using descriptive statistics.

4. Results

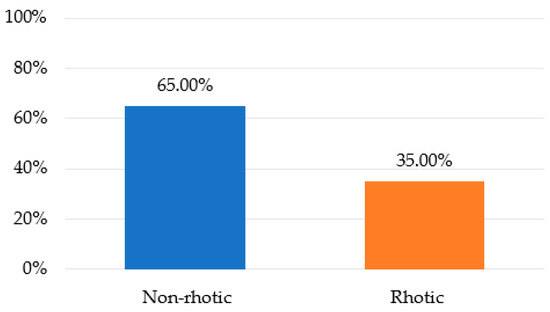

There were a total of 1180 tokens in the corpus. Figure 1 shows the overall rate of rhotic vs. non-rhotic production in the data. The singer displays rhoticity in 35% of cases where there is a non-prevocalic orthographic <r>, showing that there is variable stylization to this feature. Table 1 summarizes the best-fit regression model that includes the factors that are significant in explaining the variation observed in the performer’s rhotic production: word class, stress, lexical set, syllable complexity, elongation, and album. The interaction between word class and stress is also part of this model. The factors considered that are not part of the best-fit model include complexity of the preceding vowel, following context, location within the word, and location within the phrase.

Figure 1.

Overall rate of rhotic and non-rhotic production.

Table 1.

Best-fit model from the regression analysis.

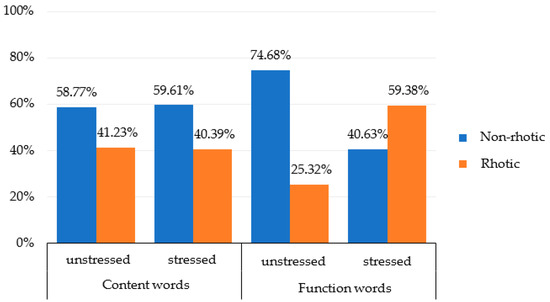

Table 1 shows that word class is a significant factor in rhotic production, with lexical words displaying higher rhoticity than function words (40.65% vs. 27.47%, respectively), and that stress also presents a significant result, with stressed contexts leading to more rhoticity than unstressed ones (41.62% vs. 30.22%, respectively). However, the interaction between these two factors is significant (p = 0.0002), suggesting that the general patterns for word class and stress change when the two factors are considered together. This significant interaction can be seen in Figure 2, which includes the rhoticity rates for word class and stress crossed together. As the figure shows, stress does not seem to impact content words, since they have a similar rhoticity rate regardless of stress. However, for function words, we observe a different pattern, namely that stressed words present a higher degree of rhoticity compared to unstressed ones. In addition, Figure 2 indicates that content words present higher rhoticity than function words, but only in unstressed positions. In stressed contexts, function words show more rhoticity than lexical words. The interaction between word class and stress stems from these patterns.

Figure 2.

Rate of rhotic and non-rhotic production by word class and stress position.

Lexical set is also a significant factor in the best-fit model above. In the descriptive analysis of the corpus, all lexical sets were considered. The distribution of rhoticity by lexical set can be seen in Table 2, which shows that there are differences based on the lexical set to which the word containing <r> belongs to. Most notably, the NURSE set shows more rhoticity than the other ones. The next group with the highest rhoticity rate includes LETTER, START, FORCE, NORTH, and CURE, and the group with the lowest rate is formed by HOUR, SQUARE, NEAR, and FIRE. Due to the low number of observations per lexical set, this factor had to be recoded to be included in the regression modeling; specifically, the lexical sets were collapsed as NURSE vs. Non-NURSE. The regression results show that the difference between NURSE and all other lexical sets is significant, with 54.65% vs. 31.65% of rhotic production, respectively (p = 0.00331).

Table 2.

Rhotic and non-rhotic production rate by lexical set.

Coda complexity is part of the best-fit model as a significant factor. Complex codas, i.e., those where the rhotic is the first coda element (e.g., heart), result in a higher rate of rhotic production compared to simple codas where <r> is not followed by another coda consonant. Table 3 shows that for complex codas, rhotics are produced close to 48%, compared to simple codas that present under 29% rhoticity.

Table 3.

Rhotic and non-rhotic production rate by coda complexity.

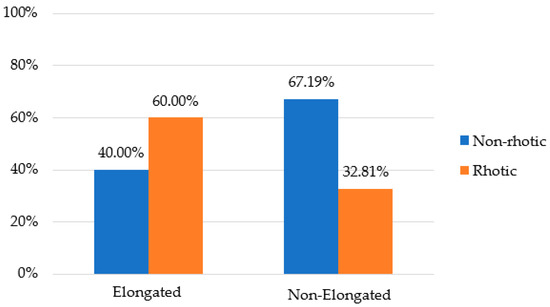

Moving on to factors directly related to singing and the band in particular, elongation is a strongly significant factor (p < 0.0001) that favors rhotic production. As Figure 3 illustrates, rhoticity is higher than non-rhoticity in elongated syllables, unlike non-elongated syllables, which follow the general pattern of non-rhotic production being the most frequent. While there were a limited number of elongated syllables that contain the target sound (N = 95), the pattern is robust. Album is also part of the best-fit model, and the results in Table 1 show that the first album is significantly different from the fourth. Releveling indicated that the fourth album is also different from the second and third ones (p ≤ 0.05). The relevant pattern, which can be seen in Table 4, is that the rhoticity rate increases from the first to the second albums, i.e., from 36.6% to 43.06%. After that, the rate decreases until it reaches the lowest rate for the fourth album (25.36%).

Figure 3.

Rate of rhotic and non-rhotic production by syllable elongation.

Table 4.

Rhotic and non-rhotic production by album.

The effect of rhyming on rhotic production was examined only through descriptive statistics given the low number of observations. Table 5 summarizes the pattern of rhyming pairs and triplets that contained the target <r> according to whether the rhyming elements agree in rhoticity, non-rhoticity, or did not agree, i.e., one rhyming element displayed rhotic production and the other was non-rhotic. The main pattern, especially observed for rhyming pairs, which had a higher amount of tokens, is that rhyming elements tend to agree in whether the rhotic is produced or not. Mirroring the general trend for overall rhoticity, most of these did not contain a rhotic (48.38%), and pairs rhyming with a rhotic was the second most common pattern (29.03%).

Table 5.

Rhoticity in rhyming pairs and triples that contain the target <r>.

Finally, 19 hyper-rhotics were identified. These are non-prevocalic rhotic productions that do not have an orthographic representation and involve innovative productions by the singer. Of these 19 hyper-rhotics, 16 occur in the first two albums, with 7 of them coming from the word “fast” in song 9 in the second album. The 11 distinct lexical items that present hyper-rhoticity were all content words (cost, doorstep, fast, foot, last, love, past, rot, walk, water, and was). Eleven of the words with hyper-rhotics occurred in the utterance final position; the other eight were located within the utterance.

5. Discussion

The current study explores linguistic and music-related constraints on stylized rhoticity, as well as changes in that stylization as the band’s musical genre evolves. The results show that the Mumford and Sons singer adopts rhotic production 35% of the time, which contrasts with his spoken accent, which is non-rhotic. This degree of rhoticity can be compared with what previous studies have reported, especially for US performers. As mentioned in Section 2.2, Gibson (2023) finds that US pop and hip hop artists present 43% rhotic production. Duncan (2017) reports that two of the three US country artists he examines produce less rhoticity in their singing than in their spoken accent. These previous findings highlight that the target for stylized rhoticity is not complete rhoticity but rather a style where rhotic production is variable and lower than in US spoken speech. This puts Mumford and Sons’ performance in context and indicates that the degree of rhotic stylization they display is considerable within US popular music norms. Furthermore, their overall pattern is similar to what Gibson (2023) reports for New Zealand performers (around 30%), Konert-Panek (2017) for Amy Winehouse (36.5%), and Trudgill (1983) for the Beatles and Rolling Stones’ early albums (36%), but it is different from Duncan’s results for Keith Urban (75%). This indicates that Mumford and Sons align with the US stylized norm for pop-rock, what Gibson (2023) calls Popular Song English, rather than with country music norms, even though the Americana genre blends in elements from other genres including country (see Section 2.2).

Addressing one of our main goals, our data show that variable stylized rhoticity is constrained by linguistics factors; that is, there is more rhotic production in lexical words, complex codas, NURSE words, and in stressed syllables, especially for function words. Linguistic constraints on variable stylization in Anglophone singing have not been systematically explored by earlier studies, so any comparison with previous findings is very limited. Gibson (2019, 2023) reports a much higher degree of rhotic production in NURSE words than words from other lexical sets, mirroring the findings from the current study. Gibson (2019) also observes more rhoticity word internally or before a pause than word finally before a consonant, something that is different in our data since word position and following context do not play a role. Trudgill (1983) mentions that rhotic production seems to be harder in unstressed syllables, echoing the pattern found in our data. However, a key question is why the contexts listed above lead to more rhoticity. The proposal put forth here is that all these contexts are perceptually more prominent or salient given their acoustic, auditory, and phonological characteristics, compared to their counterparts, i.e., function words, simple syllables, non-NURSE words, and unstressed positions. Perceptually more prominent or salient contexts would lend themselves to a higher degree of rhotic stylization because they are more noticeable to the performer and, moreover, rhoticity in prominent contexts would lead to a greater overall perception of the feature.

Evidence for the higher perceptual prominence or salience of these contexts for English comes from a range of previous studies. Lexical words are considered to bemore prominent than function words cross-linguistically. For example, Cutler (1993) explores word class-based effects on the perception of American English speakers and finds an advantage for lexical words compared to function words. The prominence of lexical words has been connected to their phonological features: they tend to occur in prosodically strong positions, unlike function words, which usually occupy weak ones, and they are more complex in syllable structure (Shi and Werker 2003; Cutler 2012). Acoustically, lexical words tend to be longer, louder, and less reduced than function words (Shi and Werker 2003). Related to rhoticity, Lavoie (2002) finds more rhotic reduction among American English speakers in the function word for than in the lexical one four. The author reports some non-rhotic productions for the former, while the latter always presents rhotic realization, and the Lavoie argues that this pattern results because function words undergo more phonetic reduction than lexical words. Coming back to singing, Prince (1987) reports an effect of word class in her analysis of dialect shift in a Yiddish singer as the performer negotiates using pronunciation features from Standard Yiddish and maintaining her local, and stigmatized, dialect of Bessarabian Yiddish. Prince predicts that lexical4 words, being more prominent, will show more of the feature that is aligned with the target pronunciation than function words. Her findings support this prediction, since the singer displays more Bessarabian Yiddish elements in lexical than function words in those cases where she wants to “sound Bessarabian”.

Cutler (2012) summarizes evidence that stressed syllables are more prominent or perceptually salient in English than unstressed ones. The former are longer, more intense, and have more energy in the upper frequencies, making them easier to be perceptually identified (Cutler 2012). Trudgill (1983) and Simpson (1999) impressionistically observe that rhotic production in singing is harder in unstressed syllables, and the current study brings quantitative data to support this observation. However, in our data, it is mainly function words that show an effect of stress. Function words are usually prosodically weak and unstressed (Lavoie 2002; Cutler 2012). In singing, stress might be placed on this type of word to fit the melody or to emphasize the word. Our findings indicate that the acoustic enhancing features of stress provide for a more favorable context for rhotic production in function words. This might be because the attention brought to the function word by the stress placement offers an opportunity to style shift in a context that will be perceptually prominent to the listener. This argument highlights that it is not only the singer’s perception but also perception by the audience that are relevant when analyzing the motivation and impact of stylization in performances (following Jansen 2018).

Recall that syllable complexity refers to whether the rhotic is followed by another consonant within the same syllable (e.g., complex heart vs. simple hair). There is acoustic evidence that rhotics are longer and more intense in complex than in simple syllables (Nelson 2011). This greater acoustic prominence would result in an advantage for rhotic perception in complex syllables. In addition, Proctor and Walker (2012) use articulatory data gathered with real-time structural MRI to compare the degree of coarticulation between a vowel and a following rhotic in simple and complex syllables and find greater overlap, or “encroachment”, with the vowel when the rhotic is part of a complex syllable. Connecting this to our study, Proctor and Walker’s (2012) findings suggest that a preceding vowel conveys articulatory information about a following rhotic to a higher degree when the syllable is complex, which would result in a perceptual enhancement of the rhotic in that context, i.e., greater prominence. The prominence of NURSE words for rhoticity can also be explained by referring to syllabic structure. Rhotics in this lexical set tend to be syllabic, while in other lexical sets, the rhotic is usually produced as following a vowel. The syllable nucleus correlates with longer duration and intensity compared to the syllable margins, and syllabic rhotics have been found to have greater intensity and be longer, i.e., more vowel-like, than non-syllabic ones. In addition, further evidence for the prominence of rhotics in NURSE words comes from acoustic studies that compare monophthongs (NURSE and LETTER words) and diphthongs (all other lexical sets). Chung and Pollock (2014) report that monophthongs have more robust cues for rhoticity in their formant patterns, namely a smaller F3-F2 distance, than diphthongs. This indicates that the cues for rhoticity are more prominent or salient in monophthongs (Chung and Pollock 2021). As mentioned, not only NURSE but also LETTER words contain a monophthong, and coming back to Table 2, we see that the latter type of words fall within the next tier of rhoticity rate after NURSE words. The difference between the two types of words is stress, with LETTER words having an unstressed syllable in the rhotic context, which might explain the lower rhoticity for these words. Summarizing, there is evidence from studies in English that the contexts that lead to more rhoticity in our data are more perceptually prominent.

The role of prominence in accent stylization in singing has been suggested by previous research. Gibson (2019) differentiates between sociolinguistic salience and auditory prominence and argues that both have an impact on singing stylization. While Gibson’s study focuses on the former, the author captures auditory prominence in his exploration of New Zealand performers by using the concept of contextual salience, which includes contexts with greater auditory and acoustic prominence and high informativity but provides only anecdotal evidence for its role. The current study supports Gibson’s hypothesis and presents quantitative results that highlight and elucidate how prominence is relevant in stylization. Yaeger-Dror (1991), in a study on Hebrew singers that informs Gibson (2019), discusses cognitive salience, which, to a great extent, overlaps with what here is called perceptual prominence, and indeed, the author mentions some of the contexts where our results show more rhoticity as contexts with greater salience that should display a higher rate of the stylized feature. Like Gibson’s (2019), our findings support Yaeger-Dror’s claim by providing evidence that perceptual prominence aligns with more stylization, in this case more rhotic production. However, the present study does not delve into the other type of salience that Gibson (2019) explores, i.e., sociolinguistic salience, while acknowledging its importance in the phenomenon under study.

The feature examined here, i.e., variable rhoticity, is also found in English dialects that are undergoing a change from being r-less to r-ful, e.g., New England English, and vice versa, e.g., West Country English. While the sociolinguistic underpinnings of these dialectal changes are different from those of rhotic stylization in singing, we can compare the linguistic constraints on this dialectal variable, as identified in previous work, with the findings of the current study. By and large, the patterns for rhotic stylization reported here show similarities with the linguistic path of dialect change observed in English varieties. Lexical words favor rhoticity in changing dialects, as reported for rhotic loss (Blaxter et al. 2019) and gain (Becker 2014). In their study of rhotic loss in Lancashire, England, Turton and Lennon (2023) report that function words are near-categorically non-rhotic, which, while illustrating a more advanced case of rhotic adoption, mirrors the finding for singing stylization. Similarly, regardless of whether the variety is losing or gaining rhoticity, stressed contexts promote rhotic presence (Nagy and Irwin 2010; Piercy 2012; Becker 2014; Blaxter et al. 2019; Turton and Lennon 2023), a pattern that also emerges in the context of stylization but with less strength than for dialect change. The type of preceding vowel has also been found to impact dialect change, with NURSE words correlating with more r-ful productions than any other lexical set (Nagy and Irwin 2010; Piercy 2012; Becker 2014; Blaxter et al. 2019). This pattern is also robust in the data analyzed here, reflecting a trend for English rhoticity that has been noted by previous authors (Gibson 2019) and, as discussed above, can be understood as stemming from the acoustic cues of the rhotic in the lexical context, where it tends to be syllabic and, consequently, acoustically prominent. Finally, while studies on dialect change and rhoticity do not refer to syllable complexity directly, many of them report more rhotic production in contexts that include complex syllables. For example, Blaxter et al. (2019) report that a following tautosyllabic consonant, i.e., a complex syllable, favors rhoticity in their study of rhotic loss in Bristol English (see also Feagin 1990; Nagy and Irwin 2010; Piercy 2012 for similar findings). These parallelisms between dialect change and stylization in singing highlight that, while the sociolinguistic reality of both contexts is different, the linguistic constraints on rhoticity follow a general tendency that likely reflects acoustic and articulatory prominence-related factors that bear on its variable production and that stylization is shaped by factors that are seen at play in other linguistic situations.

Beyond linguistic constraints, this study examines the impact of music-related factors on rhotic stylization to center singing as an artistic performance, distinct from spoken speech. Elongation, i.e., the lengthening of a syllable to sustain a note, which is ubiquitous in most musical genres but rare in spoken registers, was found to influence rhotic production in our data to a great extent. More precisely, there is over 67% rhoticity in elongated syllables, showing that rhotic production is more frequent than non-rhoticity with elongation, which is different from the overall pattern discussed at the beginning of this section. This finding contrasts with Morrissey’s (2008) prediction, discussed in Section 2.1, that non-rhotics would be preferred in sustained notes because producing a rhotic reduces sonority by introducing a higher degree of constriction than its absence does. The current data show a different pattern and suggest that sonority considerations might not be critical in this context. The English rhotic is an approximant sound; its degree of constriction is lesser compared to other rhotic sounds such as trills and taps, and it is more sonorous than other consonants in the language (Parker 2002). As a consequence, sonority differences might not be as relevant in this type of stylization as when other sounds are involved. In addition, the English rhotic is a continuant sound and can be sustained during syllabic lengthening, which contrasts with other consonants that are harder to elongate. This allows performers to enlist rhotics in elongation while singing and utilize rhotic production to add duration to lengthened syllables. Related to this finding, British singer Billy Bragg, a speaker of a non-rhotic English dialect, offers the following quote when discussing sustaining syllables: “It’s also difficult to sing harmonies in a London accent. And you can’t sustain syllables for long. I learned that to my cost with ‘Greetings To The New Brunette,’ which starts with that sustained ‘Shirrrr-LEY!’ I sound like a fucking foghorn” (Lewis 2006; as cited in Blake Bonn 2023). While the artist does not refer to the rhotic sound directly, the non-rhoticity for this word in the London dialect suggests that this pronunciation feature is at the heart of his observation.

Rhyming was explored as another music-related factor that might condition rhotic stylization. The number of observations that were part of a rhyme was low, and for this reason, the findings are limited. The main pattern that emerged, though, is that rhyming words tend to agree in being either rhotic or non-rhotic, although some rhyming pairs consisted of productions with and without a rhotic. Among the agreeing rhymes, most of them presented non-rhoticity, mirroring the overall results. On closer inspection, most non-agreeing rhymes consisted of a non-rhotic production followed by a rhotic one (7 out of 9). This suggests that there could be a priming effect so that rhoticity in the first word in a rhyme triggers rhoticity in the following rhyming element, which would explain the low number of rhymes formed by a sequence of rhotic and non-rhotic productions. While this hypothesis needs to be further explored, we find some support in Gibson’s (2019) study on stylization in NZ performers, where the author reports some priming effects of rhotic tokens that favor rhoticity in a following token.

Beyond elucidating linguistic and music-related constraints on stylization, this study also examines the role of musical style or genre by analyzing rhoticity throughout the performers’ musical career. As mentioned in Section 2.2, Mumford and Sons present a genre transition in their last two albums from Americana or folk-rock to an alt-rock sound. Results show that the degree of rhoticity in the performer’s singing decreases later in their discography, especially in their last album. Previous studies also report changes in the degree of stylization for other artists during their careers. Schulze (2014) and Flanagan (2019) find a sharp decrease in vernacular features together with an increase in USA-5 ones for the British indie band Arctic Monkeys through their discography, while Schulze (2014) finds a move towards more Scottish elements than USA-5 ones for Scottish band Biffy Clyro later in their career. These diachronic shifts in stylization have been explained as stemming from changes in performers’ motivation, access to other pronunciation models, and attitude towards the music industry (Flanagan 2019). Other scholars have analyzed some artists’ sociolinguistic style evolution over time as a strategic use of linguistic resources as they change their performative persona (e.g., see Eberhardt and Vdoviak-Markow (2020) for Beyoncé’s use of zero copula during her career and Simpson (1999) for Van Morrison’s “reinventing himself” through phonetic stylization). In the case of Mumford and Sons, we argue that the shift in stylization away from rhoticity is connected to their musical evolution from an American-roots genre (Americana) to mainstream pop-rock (alt-rock). This adds to our understanding of the role of music genre in stylization practices among singers, expanding Duncan’s (2017) findings for country music. Duncan (2017) highlights the importance of genre in stylization and connects his findings to artists’ striving for a performance that includes the features that index authenticity in country music. The current study presents further evidence for the connection between stylization and music genre by showing that performers modify their stylization as their music evolves into a different genre. Mumford and Sons’ stylization progress can be understood in two ways. On the one hand, as Southern British English speakers, the desire to sound authentic within Americana could lead them to adopt linguistic features that index Americanness, such as rhoticity. However, later in their career, that kind of authenticity loses ground as their genre shifts to alt-rock. This understanding builds off Duncan’s concept of “performing authenticity”. On the other hand, rhoticity might be part of the norm for Americana music, and the artists aim towards that norm in their earlier albums. This means that this genre is indexed by certain linguistic features that include rhoticity. As their style moves towards a different genre, the norm also shifts, and it is manifested in a reduction in rhoticity. Previous studies refer to the norm of Anglophone pop-rock (Beal 2009; Gibson and Bell 2012) when discussing stylization; in the present case study, two genres with potentially distinct norms are relevant. Questions related to authenticity, norm, and genre would benefit from a more detailed exploration that goes beyond the scope of this article.5

This shift across the band’s discography is also apparent in the performer’s production of hyper-rhotics. Hyper-rhotics are a type of hypercorrection or overshoot by which rhoticity is produced in the absence of an orthographic <r> (or a linking /r/). Bell and Gibson (2011) identify overshoot, or hyperproductions, as a sociophonetic process that performed stylizations might display. In fact, hypercorrections of rhoticity have been reported in previous studies on stylization in Anglophone popular music (Trudgill 1983; Simpson 1999; Duncan 2017), but this is one of the first studies to consider hyper-rhotics in a systematic way and to provide some quantitative data on their use. While these productions are rare in our corpus, with only 19 tokens, there are some clear trends. All of them occur in lexical words, reflecting the pattern observed for rhoticity in general, and most of these sounds occur in the first two albums. This trajectory in hyper-rhoticity aligns with the overall change found for rhotics across the band’s career. As their musical style shifts, hyper-rhotics are almost absent from their singing. Gibson (2019, 2023) argues that hypercorrections or overshoot are evidence of intentional rather than responsive style shifts, in this case, that the performers intent is to “sound American”. Gibson finds no overshoot in his corpus of NZ singers and frames this within his argument that these artists’ stylization to USA-5 features is responsive, and their use of NZ features is an intentional shift. In contrast to Gibson’s findings, the current results show hypercorrections of rhoticity, and this would indicate that the band’s stylization reflects an intentional shift. However, the motivation for such a shift changes as the band’s music style moves in a different direction in their later albums, and this has an impact on their degree of rhoticity in general and hyper-rhoticity in particular. To conclude, it is worth noting that some of the singer’s hyper-rhotics seem to be salient to listeners. A review of their second album highlights this when commenting that one of the songs “[Hopeless Wanderer] has an unfortunate pronunciation of ‘fast’ during the chorus.” (Tufts Daily 2012). This is the word produced with a hyper-rhotic seven times throughout the song. While hyper-rhoticity might lead to a higher degree of overall rhoticity and contribute to approximate the intended target feature, its impact on the audience’s perception of the performance merits further investigation.

6. Conclusions

This study examines variable rhotic stylization in the British band Mumford and Sons as they shift towards a Mid-Atlantic or USA-5 accent in their performances and highlights the ways in which this stylization is constrained or structured. First, quantitative results show that rhotic production is more common in perceptually salient contexts, a pattern that mirrors the path of dialect change from r-less to r-ful varieties of English. Rhotic production is further influenced by factors related to music and singing; notably, syllable elongation leads to more rhoticity, which we argue indicates that rhotics can be recruited to add duration. In addition, this study advances our understanding of the role that genre can play in accent stylization by quantitively analyzing the evolution of the band’s musical genre alongside their stylization practices. Results support our claim that the band singer presents stylization to a genre since his rhotic production drops later in their career as they move away from Americana music.

The analysis presented here paves the way for future research that could overcome some of the limitations of the current study. For example, while rhoticity is a salient feature of the USA-5 model, there are other features that Mumford and Sons might incorporate into their performances, especially those that pertain to vowels. Expanding the analysis to those other features would not only give us a more complete picture of the band’s stylization but would also allow us to compare the degree of shift depending on the feature. As Bell and Gibson (2011) note, performers are selective and might use certain features and not others due to difficulty or salience matters. In addition to widening the range of features, there are factors that this study does not explore that might be playing a role in the stylization, most notably lexical frequency (Konert-Panek 2018; Gibson 2019). Similarly, the topic of the song has been shown to impact stylization for some performers (Gibson and Bell 2012), and a more qualitative analysis of the corpus would allow us to examine any effect of this. Moving beyond Mumford and Sons, there has been a recognized bias towards male performers in popular music (Frith and McRobbie 2002), with some studies on singing stylization reflecting and acknowledging this bias (Coupland 2011; Gibson 2023). It behooves us as researchers to include in our analyses a wide range of singing voices that would allow us to explore gender-based differences, similar to sociophonetic studies, but also to better understand performers’ linguistic practices. Two of the top best-selling Anglophone music artists, i.e., Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, display shifts in musical genre during their career and, as we saw for Mumford and Sons, this can go hand in hand with changes in their stylization practices. Exploring such cases would also allow us to address questions of authenticity and language use in performances.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Due to copyright issues, the data cannot be made publicly available. However, the corpus of study is available to anyone that has access to purchase Mumford and Sons’ discography.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | English vowels are traditionally represented according to their lexical set (Wells 1982), which is written in all caps, e.g., BATH. In a nutshell, a lexical set refers to all the words that contain the same vowel phoneme. |

| 2 | In addition to the kind of authenticity that Duncan discusses, there is also personal authenticity (Coupland 2011), which can profoundly impact audiences’ reception and perception of an artist. Beal (2009) points at Arctic Monkeys’ use of regional features in their singing as connected to perceived authenticity. Personal authenticity is valued in popular culture in general and, while being a concept difficult to define, can be seen as “a performance of authentic identity” (Weinstock 2022; as cited in Werner 2022; see also Blake Bonn 2023). |

| 3 | On being awarded the Trailblazer Award in 2018, one of the band members stated that “we’ve never fully felt comfortable with labels that people have put on our music. To us, it’s just the sound that we make, drawing on all sorts of influences from America and elsewhere. Americana encapsulates this patchwork of influence most broadly” (Aird 2018). |

| 4 | Prince (1987) uses the terms open-class and closed-class words to refer to what in this paper we call lexical and function words, respectively. |

| 5 | See Fernández De Molina Ortés (2023) for an analysis of the role of musical genres and their norms in Spanish music. |

References

- Agha, Asif. 2003. The social life of cultural value. Language & Communication 23: 231–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, Jonathan. 2018. Mumford & Sons to Receive AMA-UK Trailblazer Award. Americana UK. Available online: https://americana-uk.com/mumford-sons-to-receive-ama-uk-trailblazer-award (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Alim, H. Samy. 2009. Translocal style communities: Hip hop youth as cultural theorists of style, language, and globalization. Pragmatics. Quarterly Publication of the International Pragmatics Association 19: 103–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, Joan C. 2009. “You’re Not from New York City, You’re from Rotherham”: Dialect and identity in British indie music. Journal of English Linguistics 37: 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Kara. 2014. (r) we there yet? The change to rhoticity in New York City English. Language Variation and Change 26: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Allan. 1984. Language style as audience design. Language in Society 13: 145–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Allan. 2001. Back in style: Reworking audience design. In Style and Sociolinguistic Variation, 1st ed. Edited by Penelope Eckert and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Allan, and Andy Gibson. 2011. Staging language: An introduction to the sociolinguistics of performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake Bonn, Mary. 2023. “That’s the Way I Am, Heaven Help Me”: The Role of Pronunciation in Billy Bragg’s Music. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter, Tam, Kate Beeching, Richard Coates, James Murphy, and Emily Robinson. 2019. Each p[ɚ]son does it th[εː] way: Rhoticity variation and the community grammar. Language Variation and Change 31: 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2020. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Carlsson, Carl Johan. 2001. The way they sing it: Englishness and pronunciation in English pop and rock. Moderna Sprak 95: 161–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Hyunju, and Karen E. Pollock. 2014. Acoustic Characteristics of Adults’ Rhotic Monophthongs and Diphthongs. Communication Sciences & Disorders 19: 113–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Hyunju, and Karen E. Pollock. 2021. Acoustic characteristics of rhotic vowel productions of young children. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 73: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbey, Rini. 2023. Americana Music: The Genre History and Top Musicians. Culture Frontier. Available online: www.culturefrontier.com/americana-music (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Coupland, Nikolas. 1988. Dialect in Use: Sociolinguistic Variation in Cardiff English. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2011. Voice, place and genre in popular song performance. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 573–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Anne. 1993. Phonological cues to open- and closed-class words in the processing of spoken sentences. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 22: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Anne. 2012. Native Listening: Language Experience and the Recognition of Spoken Words. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Daniel. 2017. Australian singer, American features: Performing authenticity in country music. Language & Communication 52: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, Maeve, and Madeline Vdoviak-Markow. 2020. “I ain’t sorry”: African American English as a strategic resource in Beyoncé’s performative persona. Language & Communication 72: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empire, Kitty. 2015. Mumford & Sons: Wilder Mind Review—De-Folked and Rocking. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/may/03/mumford-and-sons-wilder-mind-review-defolked-no-banjos (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Feagin, Crawford. 1990. The dynamics of a sound change in Southern States English: From R-less to R-ful in three generations. In Development and Diversity: Linguistic Variation across Time and Space. Edited by Jerold Edmondson, Crawford Feagin and Peter Mulhauser. Dallas: SIL International Publications in Linguistics, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández De Molina Ortés, Elena. 2023. An example of linguistic stylization in Spanish musical genres: Flamenco and Latin music in Rosalía’s discography. Languages 8: 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, Paul. J. 2019. ‘A Certain Romance’: Style shifting in the language of Alex Turner in Arctic Monkeys songs 2006–18. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 28: 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, Simon, and Angela McRobbie. 2002. On the expression of sexuality. In Music, Culture and Society: A Reader. Edited by Derek Scott. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Andy M. 2010. Production and Perception of Vowels in New Zealand Popular Music. Master’s thesis, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Andy M. 2011. Flight of the Conchords: Recontextualizing the voices of popular culture. Journal of Sociolinguistics 15: 603–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Andy M. 2019. Sociophonetics of Popular Music: Insights from Corpus Analysis and Speech Perception Experiments. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Andy M. 2023. Pop Song English as a supralocal norm. Language in Society, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Andy, and Allan Bell. 2012. Popular music singing as referee design. In Studies in Language Variation. Edited by Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy and Juan Antonio Cutillas-Espinosa. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 9, pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammy Awards. 2023. 66th Grammy Awards: Rules and Guidelines. Available online: https://naras.a.bigcontent.io/v1/static/2023RULEBOOK_11.21 (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Hayes, Elizabeth Naranjo. 2023. Meeting in the middle: Sociophonetic convergence of Bad Bunny and J Balvin’s coda/s/in their artistic performance speech. Languages 8: 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Lisa. 2018. “Britpop is a thing, damn it”: On British attitudes towards American English and an Americanized singing style. In The Language of Pop Culture. Edited by Valentin Werner. New York: Routledge, pp. 116–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Lisa, and Michael Westphal. 2017. Rihanna works her multivocal pop persona: A morpho-syntactic and accent analysis of Rihanna’s singing style. English Today 33: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konert-Panek, Monika. 2017. Americanisation versus Cockney. Accent stylisation in Amy Winehouse’s singing accent. In Ethnic and Cultural Identity in Music and Song Lyrics. Edited by Victor Kennedy and Michelle Gadpaille. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Konert-Panek, Monika. 2018. Singing accent Americanisation in the light of frequency effects: LOT unrounding and PRICE monophthongisation in focus. Research in Language 16: 155–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, Lisa. 2002. Some influences on the realization of for and four in American English. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 32: 175–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, John. 2006. Lily Allen and the London Accent in Pop Music. Time Out. Available online: https://www.johnlewisjournalist.co.uk/cockney-pop (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Lin, Yuhan, and Marjorie K. M. Chan. 2022. Linguistic constraint, social meaning, and multi-modal stylistic construction: Case studies from Mandarin pop songs. Language in Society 51: 603–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, Massimiliano. 2013. Towards a musical stylistics: Movement in Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill’. Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 22: 283–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, Franz Andres. 2008. From Liverpool to Louisiana in one lyrical line: Style choice in British rock, pop and folk singing. In Standards and Norms in the English Language. Edited by Miriam A. Locher and Jürg Strässler. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Naomi, and Patricia Irwin. 2010. Boston (r): Neighbo(r)s nea(r) and fa(r). Language Variation and Change 22: 241–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Onna A. 2011. Liquids as syllable peaks: Preconsonantal laterals in closed syllables of American English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 130 S4: 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, Renae. 2006. Australian hip hop: A sociolinguistic investigation. Australian Journal of Linguistics 26: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, Kaitlyn. 2023. Musical genres exhibit distinct sociophonetic targets: An analysis of Quebec French. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 8: 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Stephen G. 2002. Quantifying the Sonority Hierarchy. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2007. Global Englishes and Transcultural Flows. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, John. 2015. Mumford & Sons: Wilder Mind Review—More Anodyne and Generic Than Ever. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/apr/30/mumford-and-sons-wilder-mind-review (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Piercy, Caroline. 2012. A transatlantic cross-dialectal comparison of non-prevocalic/r/. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 18: 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Ellen F. 1987. Sarah Gorby, Yiddish folksinger: A case study of dialect shift. International Journal of Sociology of Language 67: 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, Michael, and Rachel Walker. 2012. Articulatory bases of sonority in English liquids. In The Sonority Controversy. Edited by Stephen Parker. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, Christin. 2014. Identity Performance in British Rock and Indie Music: Authenticity, Stylization, and Glocalization. Master’s thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin, Adam. 2016. Mumford and Sons Fail Authenticity Test as First UK Americana Chart Launches. The Independent. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/mumford-and-sons-fail-authenticity-test-as-first-uk-americana-chart-launches-a6842291.htm (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Shi, Rushen, and Janet F. Werker. 2003. The basis of preference for lexical words in 6-month-old infants. Developmental Science 6: 484–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, Michael. 1976. Shifters, linguistic categories, and cultural description. In Meaning in Anthropology. Edited by Keith H. Basso and Henry A. Selby. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 11–55. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Paul. 1999. Language, culture and identity: With (another) look at accents in pop and rock singing. Multilingua—Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 18: 343–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Erik R. 2007. Phonological and phonetic characteristics of African American Vernacular English. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 450–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1984. On Dialect: Social and Geographical Perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Tufts Daily. 2012. Mumford & Sons Branch Out on “Babel”. Available online: https://www.tuftsdaily.com/article/2012/10/mumford-sons-branch-out-on-babel (accessed on 25 March 2024).