Abstract

This paper examines patterns of gemination in child Egyptian Arabic, with a focus on how gemination functions as a repair strategy, using data from the Egyptian Arabic Salama Corpus. The findings show that the phonological development of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children of geminated consonants correlates with previously established developmental stages. Initial stages involve the acquisition of labial geminates, transitioning through an increased use of alveolar and velar geminates, to the acquisition of rhotic and lateral geminates in later phases. The findings also suggest that gemination is not merely a phonetic phenomenon in child phonology, but also shows the children’s awareness of the phonology of the dialect, especially the moraicity of vowels and consonants.

1. Introduction

In phonology, the term “geminate” refers to a consonant that is elongated or “doubled”, and is distinct in its phonemic contrast from its shorter or “singleton” counterpart, as described by Davis (2011). This phonological feature is present in a variety of languages, including but not limited to Arabic, Italian, Japanese, Berber, Finnish, Hausa, and Koasati (Kubozono 2017). Languages display variations in the positions where geminate and singleton contrasts can occur. Specifically, geminates can appear either within a single morpheme or at the juncture of multiple morphemes or words. These are referred to as ‘underlying’ geminates when they occur within a morpheme, and ‘derived’ geminates when they result from the concatenation of morphemes or words.

In child phonology, geminate acquisition has been the focus of a relatively small number of studies despite what it can tell us about the phonology of a language. Moreover, studying the acquisition of geminate consonants by children is important for several reasons. First, it sheds light on how phonological systems are internalized and reproduced by children, including, but not limited to, distinguishing between geminate and singleton consonants. This distinction is not always straightforward, as it involves perceiving and producing subtle differences in consonant duration (Payne et al. 2017), which can be challenging for children. Second, the study of geminate consonant acquisition is a window into the broader mechanisms of language acquisition and phonological development. For example, in languages where gemination is a contrastive feature, children’s ability to use and understand geminates can have significant implications for their overall language competence and communicative effectiveness (Einfeldt 2021). Third, the ways in which children deal with and produce geminates can reveal patterns of phonological simplification and modification that occur during language development. These patterns can then inform linguistic theories about the nature of phonological representations in a given language (Khattab and Al-Tamimi 2013).

Moreover, difficulties or delays in the acquisition of geminates might signal specific language impairments or broader developmental challenges, especially considering that geminates, being a longer version of their singleton counterparts, should be more perceptually salient and relatively simpler for children to produce, given the inherently slower pace of the children’s early speech articulations (Khattab and Al-Tamimi 2013).

Interestingly, gemination is sometimes used as a repair strategy to compensate for the deletion of a consonant or the reduction in a long vowel, perhaps as a means to maintain the moraic structure of the phonological word, as discussed by Ota (2003) for Japanese children. This phenomenon was also observed even among children whose linguistic exposure is limited to languages such as English or French, in which geminates are not contrastive and are infrequently encountered (Payne et al. 2012; Vihman and Majorano 2017).

Through an investigation of a previously published corpus (Salama 2015; Salama and Alansary 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018), this paper focuses on the acquisition of geminates in Egyptian Arabic, a dialect of Arabic, often referred to as Colloquial Egyptian Arabic, with a particular focus on the use of compensatory lengthening.

2. Literature Review

The exploration of phonological development across different languages reveals the role of gemination and compensatory lengthening in child language acquisition. In Finnish, Savinainen-Makkonen (2013) focused on the phonological development of Finnish-speaking children. The research investigated how Finnish children utilize geminate consonants in their early speech, examining the prominence of geminate structures in their first words. The study found that Finnish children often omit initial consonants while showing a more accurate production of medial consonants. This indicates that medial gemination, rather than stress, is a key factor in determining word production in Finnish children. For Finnish children, the medial geminate template appears to be the most salient part of a word, more so than the initial consonant, which always carries word stress. This suggests that quantity plays a significant role in early Finnish phonological acquisition.

Savinainen-Makkonen’s (2013) study highlighted that Finnish children often include geminate consonants in their early vocabulary, suggesting a pattern distinct from languages like English. It emphasizes the importance of understanding phonological development in the context of language-specific structures, showing that gemination plays a significant role in the early stages of Finnish phonological acquisition.

In Arabic, where gemination is one of the main contrastive features, Khattab and Al-Tamimi (2013) explored the early phonological development in Lebanese children. In their study, which analyzed longitudinal data from ten Lebanese children, they found that the patterns seen in Arabic-speaking children to use gemination mirrored those in children learning languages such as Estonian, Finnish, and Hindi. This observation challenges the predominantly Anglo-centric views on the prominence of initial consonants and common syllable structure acquisition patterns. The research observed that children more frequently aimed for and produced disyllabic words with geminated or lengthened consonants, a common and productive pattern in Arabic. For the creation of medial geminates, children would typically transfer length from the preceding vowel to the medial consonant, assimilate medial codas to a following consonant, or geminate an input singleton as a result of an increase in the production of multisyllabic words. The study anticipated that a resurgence of accuracy in consonant length expression, expected in the third year of life, would signify the genuine acquisition of gemination.

Related to geminates in this context is the phonological phenomenon known as ‘compensatory lengthening’. In moraic adult languages, the mora plays a part in the metrical system. Moraic languages often have phonological rules that are sensitive to the number of morae in a word or syllable, rather than just the number of syllables. In moraic theory, syllables are analyzed as being composed of one or more morae. A simple short vowel may constitute one mora. A long vowel or a diphthong may be considered to consist of two morae. A consonant can also contribute to the moraic weight, especially in the coda position, depending on the language.

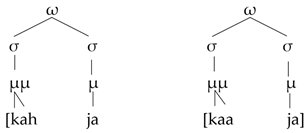

In such moraic languages, compensatory lengthening predominantly manifests in two common patterns (Gordon 2016). The first pattern involves the deletion of a coda consonant in a word, which then leads to the lengthening of an adjacent vowel. An example of this can be seen in adult Greek with the word /adras/. When the coda consonant is deleted, the word is realized as [adaas], ‘man’ with a lengthened vowel. Another example of this was also discussed by Wetzels (1986, p. 304), where a historical Greek word like */klinjō/ is produced as [klinnō], ‘tend’ in Thessalian Greek. Another example is also found in Turkish, as analyzed by Sezer (1986), where an underlying form like /kahja/ would be realized as [kaaja], ‘steward’ with a long vowel as a result of deleting the coda consonant /h/, as illustrated in (1).

| (1) | |

|

The second pattern, which is attested as a diachronic process, and usually accompanied by consonant devoicing, occurs when a word-final vowel is deleted, which results in lengthening a preceding vowel in the word, as noted in Friulian /fréde/, ‘cold FEM’→ /fréét/, ‘cold MASC’ (Hualde 1990, p. 32). In both patterns, this alteration maintains the moraic balance of the word by extending the vowel’s duration to compensate for the loss of the consonant.

In child phonology, both types of compensatory lengthening seem to be prevalent as a repair mechanism as a response to the deletion of a moraic segment. For instance, in child Japanese, Ota (2003) showed that children can geminate an input consonant as a compensatory response to vowel shortening in order to maintain the weight of the syllable, with words like /tʃootʃo/ being produced as [tʃɯttʃɯ], ‘butterfly’.

Similarly, in Arabic, Abdoh (2016) makes use of Hayes (1989) concept of “conservation law” in compensatory lengthening. In this approach, the deletion of a moraic phoneme triggers compensatory lengthening. Abdoh showed that compensatory lengthening was a prevalent occurrence among the children, with the most typical case involving the omission of a coda consonant, leading to the doubling of the adjacent consonant. For instance, the children would produce [kus.si] instead of the target word /kursi/, ‘a chair’. Abdoh’s research demonstrated that it was the omission of a moraic element that triggered gemination as a compensatory lengthening manifestation, providing support for a moraic representation in Arabic phonology.

Additionally, Mashaqba et al. (2021) showed that children acquiring Ammani Arabic do not pronounce medial clusters in an adult-like manner, as these clusters often transform into geminate consonants. In such cases, the second consonant in the cluster compensates, through gemination, for the absence of the first consonant, thereby maintaining the moraic weight and segmental length characteristic of the intended production, which would normally involve two distinct consonantal gestures.

Interestingly, previous research has shown that even in languages without a contrast in consonant length, children often produce early words with lengthened, or geminated, consonants. This was noted by Vihman and Velleman (2000), who observed that children tend to produce long consonants universally in their early speech. This phenomenon has been corroborated by studies in various languages. A possible explanation for this tendency is the slower articulation rate in children, as suggested by Khattab and Al-Tamimi (2013). This slower speech rate may lead to the production of phonetically extended consonants, a theory supported by Kunnari et al. (2001). In the field of child phonology, the study of gemination holds potential for valuable insights into the interplay between phonetic and phonological acquisition. However, this aspect has been relatively overlooked, especially in the context of Arabic phonological acquisition, as noted by Khattab and Al-Tamimi (2013).

Despite the growing body of research on gemination in child language acquisition, studies specifically focused on Egyptian Arabic are notably lacking. While previous studies have investigated the phonological development of Arabic-speaking children in various dialects, such as Lebanese Arabic (Khattab and Al-Tamimi 2013) and Ammani Arabic (Mashaqba et al. 2021), the acquisition of geminates in Egyptian Arabic has not been adequately addressed. Furthermore, although the use of gemination as a repair strategy in child phonology has been observed in other languages (e.g., Ota 2003; Abdoh 2016), the specific patterns and functions of gemination in the context of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children’s phonological development remain largely unexplored. To bridge these gaps, the present study employs a corpus-based approach, analyzing data from the Egyptian Arabic Salama Corpus (Salama 2015; Salama and Alansary 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018) to examine gemination in child Egyptian Arabic, with a particular emphasis on its role as a repair strategy. By doing so, this research aims to provide novel insights into the phonological development of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children and contribute to the broader understanding of gemination in child language acquisition.

3. Materials and Methods

The research presented in this paper is derived from the Egyptian Arabic Salama Corpus (Salama 2015; Salama and Alansary 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018), sourced from the CHILDES (Child Language Data Exchange System) database (MacWhinney 2000). This Egyptian Arabic Salama Corpus includes data from ten children, equally divided by gender, and randomly selected in Alexandria, Egypt. The children did not have any known language delays. These typically developing children, all native speakers of Arabic, ranged in age from 1 year and 7 months to 3 years and 8 months (mean = 2.77) and were studied in a cross-sectional manner. Observations included visits to seven children in their kindergarten settings and three in their homes, resulting in a total of 25,645 child utterances. Additionally, the adult component of the corpus comprised 14,868 utterances, including 2518 from mothers, 12,350 from the investigator, and 10,777 from other children (Salama 2015; Salama and Alansary 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018). The sample of children covers all three stages identified by Omar (1973), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Children with their ages and genders grouped by the stages (Omar 1973).

3.1. Data Collection

Data were gathered through unstructured interviews focusing on spontaneous speech. Elicitation methods included conversational interactions, object and picture naming exercises within the child’s environment, and the observation of play activities. This study emphasized natural interaction in various settings, such as classroom involvement, play sessions, and interactions with mothers or teachers. The interview format evolved into a semi-structured approach as children demonstrated the ability to produce morphemes.

3.1.1. Materials

The materials used to facilitate spontaneous speech included familiar objects such as toys, pictures, comics, and casual conversation topics. The focus was on using items familiar to the children to ensure their comfort and recognition.

3.1.2. Recording of the Corpus

Recordings were conducted in quiet environments, aiming for a duration of 30 min per child, totaling approximately 5 h. For children under two years, the interaction lengths varied due to their developmental needs and attention spans. Sessions were conducted intermittently to accommodate the young children’s needs, such as breaks for eating or restroom use. A 19-month-old boy’s recordings were initiated by his mother at home and continued at the nursery by the investigator. Similarly, a 2-year-and-2-month-old girl’s session was split between her mother and the investigator’s home. High-quality recording equipment (Sony/WM-GX322) and tapes were used for seven children, while the remaining three were recorded digitally using phones. Each child was informed about the recording process and displayed positive engagement, often showing interest in the recording devices. Following the sessions, the audio files were stored on a computer, and the investigator later transcribed the children’s speech, resulting in a total of 25,645 transcribed words.

3.2. Analysis Methods

The analysis in this paper relied entirely on the transcribed data available in the corpus. Instances of geminates were extracted manually and categorized into two main types. The first type is termed ‘input geminates’ to refer to geminates produced by children, which are present in the adult form. The second type, ‘output geminates’, consists of geminates that are articulated by children in words where the adult counterpart does not contain geminates, most commonly as a result of geminating one member of a heterosyllabic cluster. Input and output geminates were further categorized by the manner of articulation, place of articulation, and voicing feature.

4. Results and Discussion

In this corpus, there was a total of 655 geminates, including geminates in permissible positions (i.e., word-medial, and sometimes word-final), and including input (i.e., adult) geminates and output (i.e., made-up) geminates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Types of Geminates in the Data.

Table 2 shows trends in the phonological development of geminates. There is a clear increase in the use of geminates correlated with age, as seen in the progression from 1 year and 7 months to 3 years and 8 months. This trend is evident in the data showing that the three oldest children in the sample—Child 7, Child 9, and Child 10—account for a significant majority (69.9%) of geminates produced, despite representing only about 30% of the children observed.

Moreover, the table indicates a higher occurrence of word-medial geminates (528 instances) compared to word-final geminates (56 instances). This disparity could be attributed to the phonological processes in language acquisition. For instance, when a word ending in a geminate is followed by a word beginning with a vowel, the final geminate may phonologically transition into a medial position, splitting into the coda at the end of one word and the onset at the beginning of the next. Such a transition would naturally result in an increased count of medial geminates, which explains their predominance in the corpus.

Omar (1973, pp. 40–57) and Ammar and Morsi (2006) identified three main stages in the phonological development of Egyptian Arabic-speaking typically developing children. In Stage I (1–2 years), children learn the basic vowels /i/, /a/, and /u/ and the labial consonants /b/, /m/, and /w/ as well as the vowel-like consonant /j/, and /h/, with /ʔ/ appearing mainly as the onset of word-initial syllables. There is little distinction between voiced and unvoiced consonants or singleton and geminated consonants at this stage. In Stage II (2–3 years), phonemes such as the alveolars /t/, /d/, /s/, /z/, /n/, and /l/; the velars /k/, /ɡ/, /x/, and /ɣ/; the labiodental /f/; and the vowels /æ/, /e/, and/o/ are acquired with clearer contrasts between voiced and unvoiced sounds. Consonant clusters appear but are inconsistent and often simplified. In transitional phase II–III (3–5 years), children begin distinguishing vowel lengths as well as more challenging consonants like the emphatics /sˤ/, /zˤ/, /tˤ/, /dˤ/, or /ʕ/, /ʔ/, and /ʃ/, and sometimes /s/. Geminates in this stage are still developing but challenging, especially the velars /xx/ and /ɣɣ/. By Stage III (5 years and onwards), children have typically mastered the production of all Arabic diphthongs, such as /aj/ and /aw/, and stabilized their articulation of consonant clusters, including those that were previously simplified or reduced. Additionally, at this stage, children consistently distinguish between singleton and geminate consonants across all manners and places of articulation, which perhaps indicates a more adult-like mastery of the phonological system of Egyptian Arabic.

The data in Table 3 and Table 4 align with these phonological development stages of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children. Younger children like Child 1 and Child 2 might be in Stage I or transitioning to the next, indicated by the presence of stops and glides, which include labial sounds, and the low number of geminates overall. The absence of rhotic and lateral geminates can be linked to the fact that these sounds are typically acquired later.

Table 3.

Geminates’ Manner of Articulation.

Table 4.

Geminates’ Place of Articulation.

In Stage II (2–3 years), children start using alveolars and velars more frequently. Child 3, Child 4, and Child 5’s data show an increase in alveolar stops and fricatives (e.g., /t/, /d/, /s/, /z/), which aligns with the developmental pattern described. The presence of nasal geminates like /nn/ and /mm/ may also emerge in this stage, as seen in Table 3 and Table 4.

In transitional phase II–III (3–5 years), children begin to distinguish more challenging sounds, including geminates. Children such as Child 6, Child 8, Child 9, and Child 10, likely in this transitional phase, demonstrate an increase in the diversity of geminates, including rhotics and laterals. Table 4 shows a significant number of geminate productions, especially for Child 7, who appears to be at the upper end of this phase, nearing Stage III, given the high number of all types of geminates.

In Stage III (5 years), children have mastered most consonantal sounds, including geminates. Although the ages of the children in the latter stages are not available in the corpus, the older children, particularly Child 7, who has the highest number of geminates across all categories, could be approaching this stage. Their data indicate a stabilization in the production of geminate consonants, which signifies advanced phonological development.

The overall trend of increasing diversity and the number of geminate consonants with age observed in Table 4 is consistent with the stages of phonological development for Egyptian Arabic-speaking children as described by Omar (1973) and Ammar and Morsi (2006) for typically developing children. This progression reflects the children’s expanding phonological capabilities and their movement towards adult-like mastery of their native dialect’s phonology.

In terms of output (or made-up) geminates, there were 71 instances, divided into two main types. The first, and most common, type of output geminates (68 instances) is geminates that result from simplifying a heterosyllabic cluster by geminating one of the consonants, especially the consonant in the onset of the following syllable (Table 5).

Table 5.

Instances of Output Geminates.

The phenomenon described in Table 5 pertains especially to words starting with the Arabic definite morpheme /al-/ (a–g), where the cluster’s underlying initial consonant acts as the coda of the definite article. In Arabic phonology, the lateral sound in the definite article fully assimilates to the subsequent consonant if that consonant is coronal. However, in these instances (a–g), the second consonant in the cluster is either labial, velar, uvular, or pharyngeal—all of which are not targets of full assimilation in Arabic. This suggests that children have partially acquired the language’s assimilation rules but are overgeneralizing them to non-coronal consonants, indicating a stage in their developmental process.

The second type of output geminates results when a vowel is shortened, or segments are deleted (Table 6).

Table 6.

Other types of output geminates.

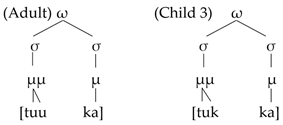

From a phonological perspective, it seems reasonable to argue that output geminates serve to maintain the moraic weight of a word or syllable. Although other types of output geminates were only observed once, their presence provides evidence of early phonological awareness of moraic structure in children. For example, Child 3 articulated the adult word form /tuuka/ as [tukka], shortening the vowel but compensating by lengthening the consonant to [kk]. This gemination maintains, as much as possible, the original moraic weight of the word, as indicated in example (2).

| (2) | |

|

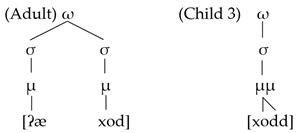

The same child demonstrated another instance of moraic preservation through gemination. In the adult pronunciation of the word [ʔæ.xod] meaning ‘I take’, which consists of two syllables and carries two morae, the child omitted the initial syllable [ʔæ] but kept the second syllable [xod]. To compensate, the child then geminated the coda, producing [xodd]. This alteration results in the preservation of the original word’s moraic weight, despite the syllabic reduction.

In the context of Cairene Arabic, a dialect of Egyptian Arabic, the principle of extrametricality explains that final singleton consonants are not counted as moraic. According to this principle, as outlined by Hayes (1995), elements at the word’s periphery (e.g., syllables, morae, vowels, consonants) can be disregarded in the construction of the metrical structure. Specifically, in Cairene Arabic, a final singleton consonant does not contribute to the moraic count of the word (i.e., extrametrical). However, as Davis and Ragheb (2014) have shown, a word-final geminate is considered to carry one mora. Therefore, by geminating the coda in [xodd], the child maintains the moraic weight of the original adult word [ʔæ.xod], as illustrated in example (3).

| (3) | |

|

Interestingly, and adding to the moraic perspective, Child 5 produced the word /kull/ as /kuul/ with a lengthened vowel for what appears to also be an example of mora maintenance.

Beyond the moraic perspective, gemination serves multiple roles in children’s language development. As they navigate the complexities of their phonological systems, children may resort to gemination to address challenges associated with pronouncing certain sounds or sound combinations, especially those that are rare or complex within their language. This strategy is not just about simplification; it also provides a practical benefit by allowing more time for transitions between sounds. By lengthening a consonant, children create a temporal buffer, facilitating a smoother and more manageable speech production process.

Gemination may also emerge as a mechanism for self-correction in speech. When children initially mispronounce a word, they may instinctively lengthen a consonant sound in subsequent attempts, aiming to correct their earlier error. This adaptive response not only aids in immediate communication but also contributes to the process of phonological adjustment and learning.

5. Conclusions

This paper examined the phonological development of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children, with a special focus on gemination. By analyzing data from the Egyptian Arabic Salama Corpus (Salama 2015; Salama and Alansary 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018), this study shows a progressive mastery of geminate consonants alongside other phonological features, aligning with previously established developmental stages of Egyptian Arabic-speaking children as described by Omar (1973) and Ammar and Morsi (2006). Initially, children acquire basic phonemes, gradually moving towards more complex ones including geminates, which serve not only as phonetic elements but also as markers of phonological awareness, particularly regarding the moraic structure of the dialect. An illustration of this phenomenon was shown in the data where some instances of (moraic) consonant deletion and vowel shortening were compensated for with gemination, which shows that gemination moraic awareness is acquired at an early age.

In addition to the insights provided by this study, the findings also have broader implications for our understanding of child language acquisition and the role of language-specific phonological features in shaping children’s early speech production. The use of gemination as a repair strategy in Egyptian Arabic-speaking children not only highlights their developing phonological awareness but also underscores the importance of considering the unique characteristics of individual languages when examining child language development. This research demonstrates that children acquiring Egyptian Arabic are attuned to the moraic structure of their language from an early age and actively employ gemination to maintain this structure in their speech. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence suggesting that children are sensitive to the prosodic features of their native language (Everhardt et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2022) and actively use this knowledge to navigate the challenges of speech production. By highlighting the specific ways in which Egyptian Arabic-speaking children utilize gemination in their early speech, this study paves the way for further research into the acquisition of language-specific phonological features and their role in shaping children’s communicative competence. Future research will look at the patterns of acquisition of other phonological aspects of Egyptian Arabic. Future research should also consider longitudinal data to track gemination development over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., F.Q. and H.B.; methodology, A.A. and F.Q.; software, A.A.; validation, A.A., F.Q. and H.B.; formal analysis, A.A. and F.Q.; investigation, A.A. and H.B.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.A. and F.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, F.Q. and H.B.; visualization, A.A. and H.B.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for funding this research through the promising program under grant number (UB-Promising-47-1445).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data was part of a publicly available corpus on the CHILDES database, which enforces strict IRB policies. Permission to use the data was obtained from CHILDES.

Informed Consent Statement

While the specific data used in this study does not include detailed information about informed consents, it is part of a publicly available corpus that adheres to these strict IRB guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

Original corpus is available at CHILDES “https://childes.talkbank.org/access/Other/Arabic/Salama.html (accessed on 15 December 2023)”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abdoh, Eman. 2016. Compensatory lengthening: Evidence from child Arabic. In Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics 27. Edited by Stuart Davis and Usama Soltan. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 215–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, Wafaa, and Ranya Morsi. 2006. Phonological development and disorders: Colloquial Egyptian Arabic. In Phonological Development and Disorders in Children. Edited by Zhu Hua. Bristol: Multilingual Matters Limited, pp. 204–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yuebo, Qinqin Luo, Maojin Liang, Leyan Gao, Jingwen Yang, Ruiyan Feng, Jiahao Liu, Guoxin Qiu, Yi Li, Yiqing Zheng, and et al. 2022. Children’s neural sensitivity to prosodic features of natural speech and its significance to speech development in cochlear implanted children. Frontiers in Neuroscience 16: 892894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, Stuart. 2011. Geminates. In The Blackwell Companion to Phonology: Vol. v. 2. Edited by Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 873–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Stuart, and Marwa Ragheb. 2014. Geminate Representation in Arabic. In Perspectives on Arabic Linguistics: Vol. XXIV–XXV. Edited by Samira Farwaneh and Hamid Ouali. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einfeldt, Marieke. 2021. Developing Sound Systems in Trilingual First Language Acquisition (Standard German, Swiss German and Italian)—The Acquisition of Consonant Inventories, Stops and Gemination. Doctoral dissertation, Universität Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Everhardt, Marita K., Anastasios Sarampalis, Matt Coler, Deniz Başkent, and Wander Lowie. 2022. Speech prosody: The musical, magical quality of speech. Frontiers for Young Minds 10: 698575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Matthew K. 2016. Phonological Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Bruce. 1989. Compensatory lengthening in moraic phonology. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 253–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical Stress Theory: Principles and Case Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, José. 1990. Compensatory lengthening in Friulian. Probus 2: 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, Ghada, and Jalal Al-Tamimi. 2013. Influence of geminate structure on early Arabic templatic patterns. In The Emergence of Phonology: Whole-Word Approaches and Cross-Linguistic Evidence. Edited by Marilyn M. Vihman and Tamar Keren-Portnoy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 374–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 2017. Introduction to the phonetics and phonology of geminate consonants. In The Phonetics and Phonology of Geminate Consonants. Vol. 2: Oxford Studies in Phonology and Phonetics. Edited by Haruo Kubozono. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnari, Sari, Satsuki Nakai, and Marilyn M. Vihman. 2001. Cross-linguistic evidence for acquisition of geminates. Psychology of Language and Communication 5: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: The Database. London: Psychology Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mashaqba, Bassil, Anas Huneety, Nisreen Al-Khawaldeh, and Baraah Thnaibat. 2021. Geminate Acquisition and Representation by Ammani Arabic-Speaking Children. International Journal of Arabic-English Studies 21: 219–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Margaret. 1973. The Acquisition of Egyptian Arabic as a Native Language. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Ota, Mitsuhiko. 2003. The Development of Prosodic Structure in Early Words: Continuity, Divergence and Change. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Elinor, Brechtje Post, Lluïsa Astruc, Pilar Prieto, and Maria del Mar Vanrell. 2012. Measuring child rhythm. Language and Speech 55: 203–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, Elinor, Brechtje Post, N. Gram Garmann, and H. Gram Simonsen. 2017. The acquisition of long consonants in Norwegian. In The Phonetics and Phonology of Geminate Consonants. Edited by Haruo Kubozono. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, Heba. 2015. Building a Spoken Arabic Corpus for Egyptian Children: Data Collection and Transcription. Master’s thesis, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, Heba, and Sameh Alansary. 2014. Building a spoken Arabic corpus for Egyptian children. Paper presented at The Fourteenth Conference on Language Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, December 3–4; Cairo: Egyptian Society of Language Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, Heba, and Sameh Alansary. 2016. Building a POS-Annotated Corpus for Egyptian Children. The Egyptian Journal of Language Engineering 3: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, Heba, and Sameh Alansary. 2017. Lexical Growth in Egyptian Arabic Speaking Children: A corpus Based Study. The Egyptian Journal of Language Engineering 4: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, Heba, and Sameh Alansary. 2018. A Morphological Analyzed Corpus for Egyptian Child Language. Paper presented at The Eighteenth Conference on Language Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, December 5–6; Cairo: Egyptian Society of Language Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- Savinainen-Makkonen, Tuula. 2013. Geminate template: A model for first Finnish words. In The Emergence of Phonology: Whole-Word Approaches and Cross-Linguistic Evidence. Edited by Marilyn M. Vihman and Tamar Keren-Portnoy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, Engin. 1986. An Autosegmental Analysis of Compensatory Lengthening in Turkish. In Studies in Compensatory Lengthening. Edited by Leo Wetzels and Engin Sezer. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 227–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihman, Marilyn M., and Shelley L. Velleman. 2000. The construction of a first phonology. Phonetica 57: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vihman, Marilyn, and Marinella Majorano. 2017. The role of geminates in infants’ early word production and word-form recognition. Journal of Child Language 44: 158–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetzels, Leo. 1986. Phonological timing in ancient Greek. In Studies in Compensatory Lengthening. Edited by Leo Wetzels and Engin Sezer. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 279–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).