Abstract

Does it matter whether charitable organizations address potential donors with an informal or formal second-person pronoun in their appeal to donate money? This study shows that it does indeed make a difference. Using an informal pronoun of address can have a positive effect on intentions to donate money. An online experiment (n = 220) found that a charitable appeal to potential donors was more effective when an informal rather than a formal second-person pronoun was used in Dutch, particularly for altruistic people. We discuss the potential explanations of this effect, concentrating on the association between the informal pronoun of address and perceived closeness, and the generic versus deictic reference of informal pronouns of address in Dutch.

1. Introduction

Consumers across different countries are willing to help good causes and donate part of their income to charities. The Dutch, for example, donated EUR 5.6 bn. to various good causes of their choice in 2020 (Bekkers et al. 2022). However, the amount of money donated to charity has remained more or less stable in recent years, and the total amount donated to charity in 2020 was only 0.7% of the Dutch GDP (Bekkers et al. 2022). Research to date has concentrated on different factors that may contribute to increasing donations to charities (Chapman et al. 2022). Calls to donate money to a charity can highlight altruistic values, commitment, empathy with the social cause, connectedness, and the organization’s true intrinsic social motives (Song and Ferguson 2023).

One stream of research on prosocial behavior concentrates on identifying the most important characteristics of people who are more willing to help (Kataria and Regner 2015; Zemack-Rugar et al. 2016). One of the traits that make people help others more is altruism, defined as the characteristic that makes people behave in a way that benefits others at their personal cost (Kerr et al. 2004). Altruists are more willing to help others (Batson and Powell 2003; Simpson and Willer 2008; van Vugt and van Lange 2006) and tend to donate more money to charities (San Martín et al. 2016). Other important characteristics of potential donors are, for instance, empathy (Lee et al. 2014; Verhaert and Van den Poel 2011), humility (LaBouff et al. 2012), or socioeconomic status, particularly, greater wealth (Bekkers et al. 2022; Schlegelmilch et al. 1997). In addition, situational factors might increase charitable donations. For instance, people who are more guilt-sensitive are more likely to buy hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products) when the purchase of the product is connected with a donation to a charity (Zemack-Rugar et al. 2016). Stress has been shown to increase pro-environmental donations, particularly among men with low pro-environmental orientation—donations helped them to restore their mood, inducing more calmness (Sollberger et al. 2016). Research has also uncovered a wide variety of charity- or cause-related characteristics that could result in higher donations, such as the perceived reputation of the charity (Meijer 2009; Trussel and Parsons 2007; Koschate-Fischer et al. 2016), trustworthiness (Meijer 2009), compassion (Bennett and Gabriel 2003), efficiency (Gneezy et al. 2014), and effectiveness (Bodem-Schrötgens and Becker 2020).

Charities could also benefit from tailoring their communication strategies toward specific groups of people more interested in helping (Chapman et al. 2022), but the research on the usage of specific linguistic strategies in designing charitable solicitations has so far been scant. Pronoun use is one way in which nonprofit organizations position themselves and their donors in an effort to gain support (Lentz et al. 2021). Macrae (2015, p. 105) noted that, since the last decade, British charity fundraising appeals have been increasingly dominated by second-person address: “Where there used to be a declarative, third person summary of the hardship of a representative sufferer, emboldened and colourful, next to an image of that sufferer, now an interrogative, directly addressed to the reader, voices the appeal for donation.” Lentz et al. (2021) analyzed pronoun use on the home and donor pages of 100 nonprofit organizations. Second-person pronouns were by far the most frequently used pronouns (Your gift to Boston Children’s Hospital helps treat the whole child), including implicit second person used in imperatives (Give monthly to help protect elephants). They were followed by first-person plural exclusive pronouns (We are proud to serve a broad and diverse patient population). In the examples throughout this article, we have bolded the relevant pronouns.

Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) investigated the impact of gain and loss frames in charitable appeals (Das et al. 2008; Erlandsson et al. 2018) in connection with the usage of first-person plural pronouns such as we or our (Our mission is to provide emotional and financial support) versus second-person pronouns such as you or your (With your donations, these kids will smile again). They found that gain-framed messages led to higher intentions to donate than loss-framed messages, but that first-person plural pronouns in loss-framed messages help boost the effectiveness of donation solicitations in comparison to second-person pronouns. They argued that messages with a loss frame emphasize the negative results of non-compliance. Hence, loss-framed messages combined with second-person pronouns will cause addressees to feel guilty, which is not a pleasant feeling for most people and thus may evoke resistance, resulting in lower donation intentions.

Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) also found that the highest intentions to donate were observed in gain-framed messages using second-person pronouns rather than first-person plural pronouns. They assumed that first-person plurals (we, our) represent inclusive and second-person pronouns (you, your) exclusive language. Hence, they claimed that first-person plural pronouns trigger a community connection, while second-person pronouns make potential donors feel like outsiders. However, the relationship between first- and second-person pronouns and the inclusivity or exclusivity of their readings is more complicated than Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) assumed. On the one hand, second-person pronouns make people feel included rather than excluded, because they are addressed and involved in the conversation. Therefore, a second-person pronoun automatically appeals to the addressee’s involvement and feelings of empathy (de Hoop and Tarenskeen 2015). On the other hand, first-person plural pronouns in English, as well as other languages, are ambiguous between an ‘inclusive’ and ‘exclusive’ reading (Lentz et al. 2021).

Inclusive we refers to a group to which the speaker and the addressee belong, while exclusive we refers to a group to which the speaker and some other person belong, but crucially not the addressee (de Schepper 2013). An example of an exclusive we is the sentence We also organized several fundraising and awareness campaigns for the fight against childhood cancer from Yilmaz and Blackburn’s loss-framed message. Clearly, the we in that sentence does not include the addressee, who most likely had no part in organizing the campaigns. The other first-person plural pronouns Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) used in the loss-framed message also refer exclusively, thus not including the addressee, e.g., To date, with the help of our donors, we helped 500 children. The donors are the donors of the organization Help Marathon (the we), but they are not the addressee’s donors. Hence, the addressee is not included in the possessive pronoun our. Lentz et al. (2021) only found 328 instances of inclusive first-person plural in their corpus of websites of charitable organizations (Let’s cure childhood cancer. Together) versus 1562 instances of exclusive first-person plural, suggesting that the first-person plural used in donation appeals is often not inclusive, pace Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022).

In fact, what Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) called ‘inclusive’ language is an example of exclusive language and the other way around. Hence, it comes as no surprise that second-person pronouns in Yilmaz and Blackburn’s (2022) study appealed to consumers more than first-person plural pronouns, and triggered the highest intentions to donate in gain-framed messages. Consumers apparently feel more addressed by second-person pronouns, because second-person pronouns are, after all, forms of address. This has a negative effect on them if the message is loss-framed, as they do not want to feel responsible for the loss, but a positive effect if the message is gain-framed, as the addressee likes to be included in the winning team.

While English only has one second-person pronoun, viz., you, other languages make a distinction between informal and formal pronouns of address, for instance, French (tu vs. vous), German (du vs. Sie), and Netherlandic Dutch (jij vs. u). Standard Netherlandic Dutch distinguishes various informal forms of second-person pronouns. The most frequently used informal form is the unstressed second-person pronoun singular je, which can be used as a subject, object, or possessive pronoun (Vismans 2013). It is the reduced (unstressed) version of the unreduced ‘full’ second-person singular pronouns jij ‘you [informal, singular, subject]’, jou ‘you [informal, singular, object]’, and jouw ‘your [informal, singular]’. Apart from the singular forms, there is the informal second-person plural pronoun jullie ‘you/your [plural]’, which may also be used to address a group of people who the speaker would address individually with the formal pronoun u ‘you [formal]’ (Vismans 2013). The formal pronouns of address u ‘you [formal]’ and uw ‘your [formal]’ can be used as a plural pronoun as well, but the plural use seems not very common anymore. In advertising, either the singular informal pronouns je/jij/jou ‘you’ and jouw ‘your’ are used, or the formal pronouns u ‘you’ and uw ‘your’, but not the plural form jullie ‘you/your’.

In this article, we are interested in whether using an informal or formal pronoun of address can increase donation intention. In the preparatory phase of this study, we noted a lack of consistency in the way charities address their potential donors on their Dutch websites. While some charities use informal pronouns in requests for donations, others show a clear preference for formal pronouns of address. For example, informal pronouns were used on the website of Alzheimer Nederland, a charity that raises money for research into Alzheimer’s disease:

- (1)

- 1 op de 5 mensen krijgt een vorm van dementie. Bij vrouwen is dit zelfs 1 op 3. Alleen door méér onderzoek kunnen we dit stoppen. Met jouw donatie kunnen onderzoekers de komende jaren blijven werken aan een toekomst zonder dementie. Help je mee voor een toekomst zonder dementie? Dat kan op veel verschillende manieren.‘1 in 5 people will develop some form of dementia. In women, it’s even 1 in 3. Only through more research can we stop this. With your [informal] donation, researchers can continue working towards a dementia-free future in the years to come. Will you [informal] help to create a future without dementia? There are many ways to do so’.

Formal pronouns were used on the website of Stichting Kinderen van de Voedselbank, a charity fighting child poverty in the Netherlands:

- (2)

- Wat kunt u doen? Uiteraard is niet iedereen in de gelegenheid om iets beschikbaar te stellen en denkt u, maar wat kan ik dan doen? Ook u kunt heel veel voor ons betekenen. Geef deze website bekendheid, plaats overal waar u maar kunt linken naar deze website, gebruik socialmedia zoals, Facebook en Twitter, om deze website bekendheid te geven. Misschien kent u mensen die iets voor de stichting kunnen betekenen, of kunt u een leuke inzamelactie opzetten. Wellicht heeft u een kind op de basisschool, en kunt u onze klavertje-vier actie met de school opzetten. Voor meer informatie stuurt u via de contactpagina een mailtje.‘What can you [formal] do? Of course, not everyone has the opportunity to donate money and you [formal] may be asking yourself: But what can I do? You [formal] too can do a lot for us. Spread the word about this website, post a link to this website wherever you [formal] can, use social media such as Facebook and Twitter to make the website known. Maybe you [formal] know people who can do something for the foundation, or you can set up a fun fundraising campaign. Perhaps you have a child in primary school and you [formal] can set up our four-leaf clover campaign with the school. For more information, send an email via the contact page’.

Pfeiffer et al. (2023) investigated the impact of linguistic style (formal vs. informal) on donation intentions. They found that the use of a formal language style in charitable appeals resulted in higher donation intentions than an informal, colloquial style. They argued that the usage of formal language signals the greater effort the charity is exerting to support their cause. Surprisingly, no research to date has explored the impact of formal versus informal pronouns of address on donations to good causes. This is even more striking if we look at the number of countries in which such variation in addressing potential donors exists.

We contribute to the current literature by investigating whether addressing consumers in donation solicitations with either formal (Dutch u ‘you’) or informal (Dutch je/jij ‘you’) pronouns of address could boost their donation behavior. Section 2 discusses previous research on the effects of employing linguistic strategies such as the use of pronouns to increase donation intentions or appreciation for a persuasive text. Section 3 describes an experiment designed to investigate the effect of using a formal or informal pronoun in donation appeals, and Section 4 presents the results of that experiment. Section 5 discusses our findings. Section 6 presents a small follow-up experiment to investigate the distribution of generic and deictic readings of the different types of pronouns, and Section 7 concludes.

2. How to Increase Donations for Nonprofits

2.1. Linguistic Strategies

As mentioned above, Pfeiffer et al. (2023) investigated the impact of formal and informal language styles on the effectiveness of charitable appeals. They found experimental evidence that charitable appeals are more effective when a formal rather than informal language style is used. One of their studies investigated charitable appeals taken from GoFundMe, an online crowdfunding platform. For this study, they coded the language style (formal versus colloquial) of 60 campaigns. They found a significant correlation between language style and the actual amount raised by that campaign. Because the campaigns varied in more dimensions than just language style, Pfeiffer et al. (2023) conducted a second study in which they experimentally tested the influence of language style on donation intentions. The formal writing style in their manipulation included formal words, more complex sentences, and no exclamation marks (e.g., Firefighters are working hard to contain the wildfires to allow individuals to return to their homes and livelihoods safely). The informal writing style contained more colloquial words, short simple sentences, and exclamation marks (e.g., Firefighters are working very hard to block off these blazes so people can return home safely!). The results of this experiment showed that participants were more likely to indicate support for the charity when presented with an appeal in a formal rather than a colloquial style.

Pfeiffer et al. (2023) argue that formal language is more congruent in communicating serious topics, and therefore increases charitable support. Importantly, although Pfeiffer et al. (2023) found greater charitable support when formal language was used, the use of pronouns was not manipulated in their study. Clearly, based on Pfeiffer et al.’s (2023) results, we might expect that using a formal pronoun of address may increase people’s intention to donate money to a good cause, compared to using an informal (colloquial) pronoun of address. It has been shown, however, that people react differently to these pronouns across various contexts. In Dutch, Jansen and Janssen (2005) explored the perception of formal and informal forms of address in functional texts, such as communication by government agencies. Their results showed that if recipients of the message are enthusiastic about its content, they become even more enthusiastic when addressed formally. Similarly, de Hoop et al. (2023) investigated the possible influence of formal versus informal forms of address in Dutch HR communication, concentrating on both invitation and rejection emails and measuring the appreciation of the company and the recruiter. They found that the formal forms of addressing resulted in more positive outcomes. By contrast, Leung et al. (2023) showed that the usage of informal address is more beneficial for brands that are perceived as warmer, and Schoenmakers et al. (2024) showed that using an informal pronoun in the slogan of a product ad leads to a higher rating of the ad than a formal one. Schoenmakers et al. (2024) concluded that using a formal second-person pronoun in a slogan of a product ad is better avoided. These four studies were all conducted in Dutch and investigated the impact of using either the informal second-person pronoun jij or je or the formal second-person pronoun u. To sum up, whereas the use of the formal pronoun led to a slightly higher appreciation in government brochures (Jansen and Janssen 2005) and HR communication (de Hoop et al. 2023), the use of the informal pronoun was more appreciated in product advertisements (Leung et al. 2023; Schoenmakers et al. 2024). This raises the question whether formal or informal second-person pronouns are more effective in fundraising appeals. One construct that might help us provide an answer to this question is altruism, broadly established as an important characteristic influencing whether people are more or less likely to help others (Kerr et al. 2004).

2.2. Altruism

A large body of literature supports the notion that altruism is connected to closeness and perceived social proximity between people (Long and Krause 2017). People are for instance more likely to be altruistic toward family members rather than strangers. Correlational evidence about the connection between the social distance within groups of people and their altruistic behavior is abundant—a plethora of research findings demonstrate that people are more altruistic toward closer rather than distant relatives, and relatives rather than non-relatives (Barber 1994; Hames 1987). Experimental evidence, further ruling out potential confounds such as sexual attraction or reciprocity (Madsen et al. 2007), corroborates these suppositions.

Closeness can be implied through informal communication, for instance in the use of informal forms of address (Stephan et al. 2010). The literature demonstrates that the usage of informal language helps to reduce the perceived psychological distance between people and has further consequences for how people behave, work together, and collaborate (Kraut et al. 1990; Bleakley et al. 2022). Building on the established relationship between closeness perceptions and altruistic behavior, we may expect that using informal forms of address in charitable appeals will be valued, particularly by people high in altruism.

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

Self-report altruism will moderate the relationship between the form of address and donation intentions so that:

- (A)

- People high in altruism will express higher donation intentions when addressed in an informal (vs. formal) way.

- (B)

- People low in altruism will not be affected by the form of address.

We investigate the use of formal and informal pronouns of address through an experimental study. Because concrete use of language and abstract use of language could either match better the informal or formal forms of address, respectively, due to the perception of the psychological distance they create (Snefjella and Kuperman 2015), we varied also the concrete or abstract presentation of the charity in our experiment to rule out this possible confound.

3. Experimental Study

3.1. Participants and Design

In total, 220 Dutch respondents (61.8% male, Mage = 30.99, SD = 11.37) participating in an experiment on Prolific were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions in a 2 (form of address: u (formal) vs. jij (informal) × 2 (construal level: concrete vs. abstract) between-subjects factorial design with a measured continuous moderator of Self-Report Altruism (SRA) (Rushton et al. 1981). Our focal dependent variable was the donation intentions to the charity used in this experiment, Trees for All.

3.2. Procedure

The experiment started with information about a lottery through which participants had a chance to win 20 euros (Touré-Tillery and Fishbach 2017). Then, respondents were introduced to the charity Trees for All and exposed to one of the donation solicitation messages, in which we varied the usage of the forms of address (formal vs. informal). In each condition, a message from the charity Trees for All was shown asking for monetary donations. Trees for All is a charity that is dedicated to planting trees in the Netherlands and abroad and thereby counterbalancing carbon emissions. Their mission is to plant new forests worldwide and to restore existing forests.

Participants in the formal form of address condition saw the message in which the formal pronoun u was used twice. In the informal condition, we replaced the formal form of address u with the informal forms jij and je, as illustrated in Table 1. Furthermore, we varied across conditions the presentation of the charity so that the respondents could either help the charity to rescue the environment (abstract construal condition) or to plant trees (concrete construal condition).

Table 1.

Slogans used in the experiment.

Table 1.

Slogans used in the experiment.

| Informal | Formal | Translation | |

| Abstract | JIJ kunt helpen het milieu te redden. Je kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren. | U kunt helpen het milieu te redden. U kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren. | ‘YOU could help rescue the environment. You can help by donating money now’. |

| Concrete | JIJ kunt helpen bomen te planten. Je kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren. | U kunt helpen bomen te planten. U kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren. | ‘YOU could help to plant trees. You can help by donating money now’. |

After the presentation of the charity, we collected our core dependent variable, intended monetary donations. Next, we also measured our moderator, of Self-Report Altruism (SRA, Rushton et al. 1981).

3.3. Moderator

We measured self-report altruism using a broadly implemented scale developed by Rushton et al. (1981). The scale consists of 20 items and is behaviorally oriented—it explores to what extent the respondents behave altruistically in their daily lives. Example items used in the scale are for instance: I have given directions to a stranger or I have given money to charity (1 = Never, 5 = Very Often, M = 2.58, SD = 0.53, α = 0.84).

3.4. Dependent Variable

As our core dependent variable, we collected intended monetary donations. We asked participants to imagine that they won EUR 20 in the lottery and inquired how much they would be willing to donate to Trees for All in case this happened (Touré-Tillery and Fishbach 2017, M = 6.71, SD = 5.96).

4. Results

We started our analysis with PROCESS macro model 3 (Hayes 2018), exploring whether the effectiveness of donation solicitation depends on the pronoun of address (effect-coded, formal [−1] vs. informal [1]), the way the charity is presented (effect-coded, concrete [−1] vs. abstract [1]), and the altruism level (mean-centered; Rushton et al. 1981). None of the main effects were significant (Pronoun: β = 0.72, t(212) = 1.82, p = 0.07; Charity Presentation: β = 0.28, t(212) = 0.71, p = 0.48; Altruism: β = 1.90, t(212) = 2.51, p = 0.01, η2 = 0.03). The three-way interaction between the form of address, the presentation of the charity, and the altruism was not significant (β = 0.61, t(212) = 0.40, p = 0.69). The complete overview of the regression model can be found in Table 2. The presentation of the charity in either abstract or concrete terms did not affect the amount of money respondents were willing to donate to Trees for All. As a result, we collapsed both conditions presenting the charities either in an abstract or in a concrete way for subsequent analyses.

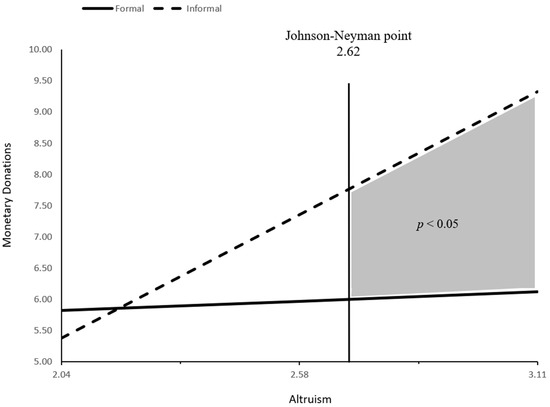

We ran a follow-up linear regression using PROCESS macro model 1 (Hayes 2018) to test the two-way interaction between the usage of a specific form of address (effect-coded, formal [−1] vs. informal [1]) and the altruism level (mean-centered) on monetary donations. We did not observe a main effect of the pronoun based on this analysis (β = 0.69, t(216) = 1.78, p = 0.07), but there was a main effect of altruism (β = 1.99, t(216) = 2.72, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.03). Moreover, the analysis revealed a significant two-way interaction between the form of address and the altruism level, β = 1.71, t(216) = 2.34, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.03 (complete overview of the regression model can be found in Table 3). In monetary terms, participants who scored 1SD above the mean altruism level in the sample (M + 1SD = 3.11) indicated that they are willing to donate EUR 3.21 more when addressed with informal (vs. formal) forms of address.

We probed the interaction between the form of address and the altruism level using the Johnson–Neyman technique (Spiller et al. 2013). To enhance the interpretability of the results, we used the raw scores of altruism in this analysis. One cut-off point at which the form of address significantly starts to influence donation intentions was identified. Respondents indicated that they would be willing to donate more money while being addressed with the informal form of address at a high level of altruism—2.62 (M + 0.08SD). At this value, the informal form of address started to exert a significant positive effect on donation intentions, BJN = 0.77, SE = 0.39, p = 0.05. 46.36% of respondents scored higher on altruism than this cut-off value.

Figure 1 illustrates our finding that respondents high in altruism were willing to donate more money to the charity Trees for All after they had been addressed with an informal rather than formal form of address.

Table 2.

Moderation model between the pronoun, charity presentation, and altruism on monetary donation intentions.

Table 2.

Moderation model between the pronoun, charity presentation, and altruism on monetary donation intentions.

| Variables | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronoun | 0.72 | 1.82 | 0.07 | [−0.06, 1.49] |

| Charity Presentation | 0.28 | 0.71 | 0.48 | [−0.49, 1.06] |

| Altruism | 1.90 | 2.51 | 0.01 | [0.41, 3.39] |

| Pronoun × Charity Presentation | −0.43 | −1.10 | 0.27 | [−1.21, 0.34] |

| Pronoun × Altruism | 1.80 | 2.39 | 0.02 | [0.31, 3.29] |

| Charity Presentation × Altruism | −0.53 | −0.70 | 0.49 | [−2.02, 0.96] |

| Pronoun × Charity Presentation × Altruism | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.69 | [−1.18, 1.80] |

Table 3.

Moderation model between the pronoun and altruism on monetary donation intentions.

Table 3.

Moderation model between the pronoun and altruism on monetary donation intentions.

| Variables | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronoun | 0.69 | 1.78 | 0.08 | [−0.08, 1.46] |

| Altruism | 1.99 | 2.72 | 0.01 | [0.55, 3.44] |

| Pronoun × Altruism | 1.71 | 2.34 | 0.02 | [0.27, 3.16] |

Figure 1.

Interaction effect between the form of address and altruism.

5. Discussion

The results of our study show that being addressed with an informal pronoun of address increases donation intentions compared to being addressed with a formal pronoun of address, at least among altruists. Although this is what we could have expected based on the assumption that the use of informal address may create a sense of greater closeness (cf. Stephan et al. 2010, p. 269), and is also more appreciated in product advertising (Leung et al. 2023; Schoenmakers et al. 2024), our results seem to contradict Pfeiffer et al.’s (2023) finding that a formal language style is more effective than an informal style in charitable appeals. How can we explain the fact that in the context of charitable contributions, calls for monetary donations written in a formal language style are more persuasive than in an informal language in English (Pfeiffer et al. 2023), while the use of an informal pronoun of address is more effective than the use of a formal one in Dutch? Below, we aim to provide an explanation for the difference in persuasiveness between an informal and a formal pronoun of address in this context, which, to our knowledge, has not previously been proposed in the literature.

The question is how to explain the difference we found between informal and formal pronouns of address in a slogan for the benefit of a social cause. Indeed, both pronouns are second person and thus have the power to address potential donors directly and get them involved. The English second-person pronouns in the fundraising study of Yilmaz and Blackburn (2022) are assigned generic meanings. When the second-person pronoun receives a generic reading, it does not refer (exclusively) to the addressee, but rather to people in general, or to a subset of people, which may include the speaker as well as the addressee (van der Auwera et al. 2012; de Hoop and Tarenskeen 2015).

Orvell et al. (2020) in a series of rating studies found that the generic use of the English second-person pronoun you causally promotes resonance. Statements containing generic you such as Sometimes, you have to take a step back before you can take a step forward resonated more with participants than statements with a first-person pronoun Sometimes, I have to take a step back before I can take a step forward, but also more than generic statements about people in general, such as Sometimes, people have to take a step back before they can take a step forward. These findings support the idea that generic you is effective not only because it generalizes over people, but also because it simultaneously addresses the reader. The fact that generically used second-person pronouns reinforce resonance between people and ideas (Orvell et al. 2020) is probably the reason for their widespread use in various contexts, such as advertisements (Christopher 2012), educational texts (Sangers et al. 2022), and charity fundraising (Macrae 2015). Generalizations are known to have an inclusive effect in the sense that interlocutors use them to emphasize their mutual agreement (Scheibman 2007). de Hoop and Tarenskeen (2015) assume that addressees will feel directly addressed by a second-person pronoun, even if it is clear that the second-person pronoun does not specifically, or deictically refer to them, as in Today, Help Marathon asks for your help again (example taken from the stimulus material of Yilmaz and Blackburn 2022, boldface is ours). In declarative sentences such as You only live once, the generic reading including the addressee is preferred over the deictic reading that exclusively refers to the addressee (van der Auwera et al. 2012; de Hoop and Tarenskeen 2015).

The question is whether in languages that do have formal and informal second-person pronouns, they can both refer deictically as well as generically. Helmbrecht (2015) notes that in German, the informal second-person pronoun du ‘you’ in (3a) as well as the formal pronoun Sie ‘you’ in (3b) can have a generic reading. However, Helmbrecht (2015, p. 178) notes that the “distinction between a familiar and a more distant polite relationship is preserved” in that in (3a) “the hearer/addressee has most likely a close relationship to the speaker”, while in (3b) “there is most likely a distant relationship between speaker and hearer”.

- (3)

- a. Leckeren Käse kannst du in dem Laden da nicht finden.b. Leckeren Käse können Sie in dem Laden da nicht finden.

‘You can’t find delicious cheese in that grocery store’.

Salvador et al. (2022) showed that, apart from the distinct generic person marker se, speakers of Spanish use the informal pronoun tú ‘you’ generically to convey norms, but not the formal pronoun usted ‘you’. Because the informal pronoun is used when the speaker and addressee are on the same level, the preferred use of informal you in Spanish suggests that its generic use “may be serving a more equalizing rather than distancing function” (Salvador et al. 2022, p. 6).

If indeed informal pronouns of address that are used generically maintain their function to express closeness, unlike formal pronouns of address, our findings provide support for the hypothesis put forward in Section 2 that closeness perceptions in relation to altruistic behavior lead to more favorable responses when informal pronouns of address are used in charitable appeals compared to formal pronouns of address.

In Dutch, the two types of pronouns of address, the informal and formal one, differ in how frequently they obtain generic and deictic readings. In a study of spoken Dutch, de Hoop and Tarenskeen (2015) found that 66% of the informal second-person pronouns functioning as the subject of a declarative sentence receives a generic reading, versus 34% a deictic reading. Indeed, Je leeft maar één keer ‘You [informal] only live once’ straightforwardly has a generic reading, just like its English translation. However, when we replace the informal pronoun by the formal pronoun, U leeft maar één keer ‘You [formal] only live once’, the deictic reading arises: ‘You [pointing to a specific addressee] only live once’. de Hoop and Hogeweg (2014) found that the formal second-person pronoun, unlike the informal one, almost never received a generic reading in the literary work they studied.

In the advertisement that we used in our experiment, the second sentence contains the request for money. The informal pronoun je in Je kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren ‘You [informal] can help by donating money now’ gives rise to a generic reading (the information applies to anybody), while the formal pronoun u in U kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren ‘You [formal] can help by donating money now’ rather seems to have a deictic reading. Thereby, the latter statement is interpreted as a directive, urging the addressee to act. Directives often contribute to the face-threatening force of an utterance (de Hoop et al. 2016), and thus the use of a formal pronoun of address can be perceived as a negative politeness strategy, in recognition of the addressee’s need for distance and the absence of identity overlap (Vismans 2013, p. 165). The use of a clear directive instead of a generic statement may result in the addressee’s resistance, leading to lower intentions to donate. Zemack-Rugar et al. (2017) found that (committed) consumers responded more negatively to a directive (Buy now!) than to a non-directive ad (Now is a good time to buy!), even when the directive ad was phrased more politely by adding please (Please buy now!). This shows that rather than the use of a polite or formal pronoun, it may be the use of a directive, although it is a very common marketing practice, that consumers respond more negatively to.

While a generalization evokes a sense of connectedness, a directive appeals to the consumer to perform a particular action that serves the sender’s interest. Not surprisingly, such a directive can evoke resistance as opposed to a generic statement. We suspect that in the generic context of charitable appeals, the difference in default reading between the two pronouns (generic for the informal pronoun je, but deictic for the formal pronoun u) may explain the difference in their effects, rather than their being informal or formal per se. However, as can be seen in Table 1 above, the informal slogan contained not only the informal pronoun je, which is easily given a generic reading, but also the strong (unreduced) second-person pronoun jij, which seems more likely to receive a deictic reading (Gruber 2017; de Hoop and Hogeweg 2014). To test whether the sentences in the experiment’s slogans were more likely to receive a generic or a deictic interpretation, the next section reports on a small follow-up experiment we conducted in which the generic or deictic interpretation of the three types of second-person pronouns je, jij, and u was explicitly questioned (cf. Orvell et al. 2020).

6. Follow-Up Experiment on Deictic and Generic Readings of Dutch Address Pronouns

To find out whether the three second-person pronouns used in the main experiment obtain a generic or a deictic reading, a small online experiment was conducted. A total of 122 respondents, all first speakers of Dutch ranging in age from 19 to 77 (M = 42) completed one of three versions of an online questionnaire, administered through Qualtrics. After they had received general information, had given consent and confirmed they were 16 years or older and first speakers of Dutch, they were presented with 9 stimuli (3 subsets of 3 sentences each) and 9 fillers in a randomized order. For each sentence, participants had to answer the question ‘Which is most likely?’ with two response options, corresponding to a deictic and a generic reading, respectively: 1. ‘The statement refers to one specific person’; 2. ‘The statement refers to (a group of) people in general’. The three subsets of stimuli contained the three types of second-person pronouns, je, jij, and u. The 9 fillers were the same for each version and contained first- and third-person pronouns (2x ik ‘I’, 2x hij ‘he’, 2x zij ‘she’, 3x men ‘one’). The pronouns were used as grammatical subject in all 18 sentences. The experimental design of the stimuli is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Experimental design with the numbers of stimuli in the three versions. Each subset contained three items.

Table 4.

Experimental design with the numbers of stimuli in the three versions. Each subset contained three items.

| Stimuli | Version 1 | Version 2 | Version 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subset 1 | jij | u | je |

| Subset 2 | u | je | jij |

| Subset 3 | je | jij | u |

One subset contained the three sentences used in the main experiment (see Table 1 above). The eighteen sentences were randomized for each participant, but care was taken that the three sentences from the main experiment were not presented as the first or last question, nor were they presented adjacent to each other. Each participant thus read the three experimental sentences with either jij, je, or u, and two subsets of three sentences each with the other two pronouns. All stimuli are listed in Table 5 below.

Because in the main experiment both jij and je were used in the informal condition, it is not possible to determine whether the difference found between the formal and informal condition in the main experiment is indeed due to the level of formality, or whether it may be influenced by a difference between deictic and generic readings of the different types of pronouns. The results of the current experiment may shed some light on this. We expected that all three types of second-person pronouns could receive a generic reading, but only for the informal pronoun je would this be the most likely reading, whereas for the pronouns jij and u, the deictic reading (exclusively referring to the addressee) would be the most likely. However, the results show a different pattern. Table 5 shows the numbers of deictic versus generic responses for the nine stimuli. The sentences in the table are in ascending order from most deictic to most generic.

Table 5.

Deictic/generic readings of experimental items.

Table 5.

Deictic/generic readings of experimental items.

| Stimuli | Numbers Deictic/Generic Reading (% Generic Reading) | Deictic: Generic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JE | JIJ | U | ||

| (1) Ben(t) je/jij/u binnenkort jarig? ‘Are you having a birthday soon?’ | 34/8 (19%) | 38/2 (5%) | 28/12 (30%) | 3:0 |

| (2) Je/jij/u moet een helm op. ‘You have to wear a helmet’. | 16/24 (60%) | 39/1 (3%) | 16/26 (62%) | 1:2 |

| (3) Soms moet je/jij/u een stapje terug doen. ‘Sometimes you have to take a step back’. | 5/35 (88%) | 35/4 (10%) | 17/25 (60%) | 1:2 |

| (4) Je/jij/u mag hier niet roken. ‘You are not allowed to smoke here’. | 4/38 (90%) | 33/7 (18%) | 12/27 (69%) | 1:2 |

| (5) Je/jij/u leeft maar één keer. ‘You only live once’. | 4/36 (90%) | 32/8 (20%) | 17/25 (60%) | 1:2 |

| (6) Je/jij/u bent van harte welkom in onze winkel. ‘You are most welcome to visit our store’. | 8/34 (81%) | 23/17 (43%) | 1/39 (98%) | 1:2 |

| (7) Je/jij/u kunt helpen bomen te planten. ‘You could help to plant trees’. | 4/36 (90%) | 14/28 (67%) | 10/30 (75%) | 0:3 |

| (8) Je/jij/u kunt helpen het milieu te redden. ‘You could help rescue the environment’. | 3/37 (93%) | 14/28 (67%) | 9/31 (78%) | 0:3 |

| (9) Je/jij/u kunt helpen door nu geld te doneren. ‘You can help by donating money now’. | 3/37 (93%) | 9/33 (79%) | 7/33 (83%) | 0:3 |

While some of the filler sentences received a 100% score on either the deictic reading (e.g., Hij moet nu wel kiezen ‘He has to choose now’) or the generic reading (e.g., Men moet beter naar elkaar luisteren ‘People need to listen to each other better’), there was more variation in the experimental stimuli, as shown in Table 5 above. Sentence (1) (‘Are you having a birthday soon?’) was the only item that was most likely to have a deictic reading for all three types of second-person pronouns. Notably, the three sentences (7)–(9) used in the main experiment (‘You could help to plant trees’, ‘You could help rescue the environment’, ‘You can help by donating money now’) were most likely to have a generic reading for all three types of pronouns. Also, while the informal pronoun je was more likely to have a generic reading than a deictic reading in all sentences except for (1), the same holds for the formal pronoun u, which we had not expected. The informal pronoun jij was overall more likely to have a deictic reading than a generic reading, namely, in six out of nine sentences. Only in the three sentences used in the main experiment, jij was more likely to have a generic reading than a deictic reading, just like the other two pronouns. Therefore, we reject the hypothesis that je was interpreted generically in the main experiment, while u and jij were interpreted more deictically. The reason that the formal pronoun u has a generic reading rather than a deictic reading might be due to the fact that u can also be used for plural reference, which is not the case for jij (Aalberse and Meyer submitted). Apparently, however, a context calling on the addressee to donate money to plant trees or save the environment is enough to evoke a generic reading of jij as well. Based on this, we conclude that it is indeed the use of informal rather than formal pronouns of address that give rise to higher donation intention among altruistic participants.

7. Conclusions

The main finding of our study is that an appeal to potential donors to donate money to an existing charity (Trees for All) is more effective when informal rather than formal second-person pronouns are used in Dutch, particularly for altruistic people. Our results contribute to the literature that aligns nonprofit organizations’ communications with donor characteristics to increase their helping behavior (Kolhede and Gomez-Arias 2022; Lv and Huang 2024). Generic uses of second-person pronouns are known to promote resonance between people and ideas (Orvell et al. 2020). The Dutch informal second-person pronoun je commonly has such a generic meaning (de Hoop and Tarenskeen 2015; de Hoop and Hogeweg 2014), whereas this is less common for the informal second-person pronoun jij and the formal second-person pronoun u. Nonprofit organizations could strategically use the common informal second-person pronoun je in Dutch, which by default has a generic reading, to motivate altruistic consumers to donate money without making them feel too personally addressed. However, the small experiment reported in Section 6 showed that within the context of charities and donations, the formal pronoun u and even the informal pronoun jij also give rise to a generic reading. We thus conclude that our main finding should be attributed to the difference in formality between je/jij and u and not to a difference between generic and deictic reference.

Our results demonstrate that when charities design their communication strategies to focus primarily on people with higher altruism, it would be more beneficial to consistently use informal forms of address. The question then arises: how can charities be sure that their intended donors are altruistic at any given time? One possible piece of advice is to at least use informal forms of address in all communications with people who have donated significantly in the past. For example, the Red Cross in the Netherlands regularly distributes mailings to people who have donated to this charity before, outlining in those messages the current needs of the organization and its beneficiaries. Based on our findings, we would recommend using informal forms of address in such forms of communication.

Our article presents findings of one experimental study conducted in the Netherlands. More research on the impact of different forms of address on charitable donations in other languages is desirable. The literature shows that the impact of the usage of linguistic cues such as second-person pronouns on people’s attitudes can vary not only by language, but also by culture and context (House and Kádár 2020; Truan 2022; Yu et al. 2017; de Hoop et al. 2023; Schoenmakers et al. 2024; Razzaq et al. 2024; Rosseel et al. 2024). Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate whether the results we presented also apply to other languages or cultures. Moreover, field experiments with real behavioral data could further replicate our results in real-life settings. Last, but not least, our findings demonstrate linguistic strategies that are successful in influencing the behavior of people with higher altruism. We believe that unraveling communication strategies that could be more effective for people with lower altruism is another fruitful avenue for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and S.S.; methodology, S.S. and L.M.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and H.d.H.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and H.d.H.; visualization, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as part of the master’s program in which the third author was enrolled as a student at Maastricht University, the Netherlands. The first author has further developed this line of research at Radboud University, Nijmegen and obtained a positive assessment from the Ethics Assessment Committee Humanities, Radboud University (#2022-7926) for experiments with a very similar design.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in a Radboud Data Repository at https://doi.org/10.34973/d1r0-q798.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers of this paper for constructive comments. Also, we are grateful to the participants of the seventh workshop of the International Network of Address Research (INAR 7), held at Radboud University, Nijmegen in July 2023, for their feedback on our presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aalberse, Suzanne P., and Caitlin M. Meyer. Submitted. Pronoun mixing in Dutch revisited: Perception of ‘u’ and ‘jij’ use by 4-vwo students.

- Barber, Nigel. 1994. Machiavellianism and altruism: Effect of relatedness of the target person on Machiavellian and helping attitudes. Psychological Reports 75: 403–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, and Adam A. Powell. 2003. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In Handbook of Psychology: Personality and Social Psychology. Edited by Theodore Millon and Melvin J. Lerner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 5, pp. 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, René, Barbara Gouwenberg, Stephanie Koolen-Maas, and Theo Schuyt. 2022. Geven in Nederland 2022: Maatschappelijke betrokkenheid in kaart gebracht. [Giving in the Netherlands 2022: Social Engagement Mapped]. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Roger, and Helen Gabriel. 2003. Image and reputational characteristics of UK charitable organizations: An empirical study. Corporate Reputation Review 6: 276–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, Anna, Daniel Rough, Justin Edwards, Philip Doyle, Odile Dumbleton, Leigh Clark, Sean Rintel, Vincent Wade, and Benjamin R. Cowan. 2022. Bridging social distance during social distancing: Exploring social talk and remote collegiality in video conferencing. Human–Computer Interaction 37: 404–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodem-Schrötgens, Jutta, and Annika Becker. 2020. Do you like what you see? How nonprofit campaigns with output, outcome, and impact effectiveness indicators influence charitable behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 49: 316–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Cassandra M., Winnifred R. Louis, Barbara M. Masser, and Emma F. Thomas. 2022. Charitable Triad Theory: How donors, beneficiaries, and fundraisers influence charitable giving. Psychology & Marketing 39: 1826–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Anne A. 2012. Deixis and personalization in ad slogans. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 6: 517–21. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Enny, Peter Kerkhof, and Joyce Kuiper. 2008. Improving the effectiveness of fundraising messages: The impact of charity goal attainment, message framing, and evidence on persuasion. Journal of Applied Communication Research 36: 161–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, Helen, and Lotte Hogeweg. 2014. The use of second person pronouns in a literary work. Journal of Literary Semantics 43: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, Helen, and Sammie Tarenskeen. 2015. It’s all about you in Dutch. Journal of Pragmatics 88: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, Helen, Jetske Klatter, Gijs Mulder, and Tijn Schmitz. 2016. Imperatives and politeness in Dutch. Linguistics in the Netherlands 33: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoop, Helen, Natalia Levshina, and Marianne Segers. 2023. The effect of the use of T or V pronouns in Dutch HR communication. Journal of Pragmatics 103: 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, Kees. 2013. You and Me against the World? First, Second and Third Person in the World’s Languages. Utrecht: LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsson, Arvid, Artur Nilsson, and Daniel Västfjäll. 2018. Attitudes and donation behavior when reading positive and negative charity appeals. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 30: 444–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, Uri, Elizabeth A. Keenan, and Ayelet Gneezy. 2014. Avoiding overhead aversion in charity. Science 346: 632–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, Bettina. 2017. Temporal and atemporal uses of ‘you’: Indexical and generic second person pronouns in English, German, and Dutch. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 20: 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, Raymond. 1987. Garden labor exchange among the Ye’kwana. Ethology and Sociobiology 8: 259–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs 85: 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmbrecht, Johannes. 2015. A typology of non-prototypical uses of personal pronouns: Synchrony and diachrony. Journal of Pragmatics 88: 176–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, Juliane, and Dániel Z. Kádár. 2020. T/V pronouns in global communication practices: The case of IKEA catalogues across linguacultures. Journal of Pragmatics 161: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Frank, and Daniël Janssen. 2005. U en je in Postbus 51-folders. [V and T in PO Box 51 brochures.]. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing 27: 214–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kataria, Mitesh, and Tobias Regner. 2015. Honestly, why are you donating money to charity? An experimental study about self-awareness in status-seeking behavior. Theory and Decision 79: 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Benjamin, Peter Godfrey-Smith, and Marcus W. Feldman. 2004. What is altruism? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19: 135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolhede, Eric, and J. Tomas Gomez-Arias. 2022. Segmentation of individual donors to charitable organizations. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 19: 333–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, Nicole, Isabel V. Huber (née Stefan), and Wayne D. Hoyer. 2016. When will price increases associated with company donations to charity be perceived as fair? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44: 608–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, Robert E., Robert S. Fish, Robert W. Root, and Barbara L. Chalfonte. 1990. Informal communication in organizations: Form, function, and technology. In Human Reactions to Technology: Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Edited by Stuart Oskamp and Shirlynn Spacapan. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, pp. 145–99. [Google Scholar]

- LaBouff, Jordan Paul, Wade C. Rowatt, Megan K. Johnson, Jo-Ann Tsang, and Race McCullough Willerton. 2012. Humble persons are more helpful than less humble persons: Evidence from three studies. The Journal of Positive Psychology 7: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Saerom, Karen P. Winterich, and William T. Ross, Jr. 2014. I’m moral, but I won’t help you: The distinct roles of empathy and justice in donations. Journal of Consumer Research 41: 678–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, Paula, Kristen Getchell, James Dubinsky, and Mary Katherine Kerr. 2021. Pronouns, Positioning, and Persuasion in Top Nonprofits’ Donor Appeals. International Journal of Business Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Eugina, Anne-Sophie I. Lenoir, Stefano Puntoni, and Stijn M. J. van Osselaer. 2023. Consumer preference for formal address and informal address from warm brands and competent brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology 33: 546–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Mark C., and Eleanor Krause. 2017. Altruism by age and social proximity. PLoS ONE 12: e0180411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Linxiang, and Minxue Huang. 2024. Can personalized recommendations in charity advertising boost donation? The role of perceived autonomy. Journal of Advertising 53: 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, Andrea. 2015. ‘You’ and ‘I’ in charity fundraising appeals. In The Pragmatics of Personal Pronouns. Edited by Laure Gardelle and Sandrine Sorlin. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, Elainie A., Richard J. Tunney, George Fieldman, Henry C. Plotkin, Robin I. M. Dunbar, Jean-Marie Richardson, and David McFarland. 2007. Kinship and altruism: A cross-cultural experimental study. British Journal of Psychology 98: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, May-May. 2009. The effects of charity reputation on charitable giving. Corporate Reputation Review 12: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvell, Ariana, Ethan Kross, and Susan A. Gelman. 2020. “You” speaks to me: Effects of generic-you in creating resonance between people and ideas. Psychological and Cognitive Sciences 117: 31038–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, Bruce E., Aparna Sundar, and Edita Cao. 2023. The influence of language style (formal vs. colloquial) on the effectiveness of charitable appeals. Psychology & Marketing 40: 542–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, Ali, Wei Shao, and Sara Quach. 2024. Meme marketing effectiveness: A moderated-mediation model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 78: 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Laura, Eline Zenner, Fabian Faviana, and Bavo Van Landeghem. 2024. The (lack of) salience of T/V pronouns in professional communication: Evidence from an experimental study for Belgian Dutch. Languages 9: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, Philippe J., Roland D. Chrisjohn, and G. Cynthia Fekken. 1981. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Personality and Individual Differences 2: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, Cristina E., Ariana Orvell, Ethan Kross, and Susan A. Gelman. 2022. How Spanish speakers express norms using generic person markers. Scientific Reports 12: 5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, René, Youngbin Kwak, John M. Pearson, Marty G. Woldorff, and Scott A. Huettel. 2016. Altruistic traits are predicted by neural responses to monetary outcomes for self vs. charity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 11: 863–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangers, Nina, Jacqueline Evers-Vermeul, and Hans Hoeken. 2022. Addressing the student: Voice elements in educational texts. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 11: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibman, Joanne. 2007. Subjective and intersubjective uses of generalizations in English conversations. In Stancetaking in Discourse. Edited by Robert Englebretson. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, Bodo B., Alix Love, and Adamantios Diamantopoulos. 1997. Responses to different charity appeals: The impact of donor characteristics on the amount of donations. European Journal of Marketing 31: 548–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, Gert-Jan, Jihane Hachimi, and Helen de Hoop. 2024. Can you make a difference? The use of (in)formal address pronouns in advertisement slogans. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 36: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Brent, and Robb Willer. 2008. Altruism and indirect reciprocity: The interaction of person and situation in prosocial behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly 71: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snefjella, Bryor, and Victor Kuperman. 2015. Concreteness and psychological distance in natural language use. Psychological Science 26: 1449–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollberger, Silja, Thomas Bernauer, and Ulrike Ehlert. 2016. Stress influences environmental donation behavior in men. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Baobao, and Mary Ann Ferguson. 2023. The importance of congruence between stakeholder prosocial motivation and CSR attributions: Effects on stakeholders’ donations and sense-making of prosocial identities. Journal of Marketing Communications 29: 339–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, Stephen A., Gavan J. Fitzsimons, John G. Lynch, and Gary H. McClelland. 2013. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research 50: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Elena, Nira Liberman, and Yaacov Trope. 2010. Politeness and psychological distance: A construal level perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 268–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touré-Tillery, Maferima, and Ayelet Fishbach. 2017. Too far to help: The effect of perceived distance on the expected impact and likelihood of charitable action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 112: 860–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truan, Naomi. 2022. (When) can I say du to you? The metapragmatics of forms of address on German-speaking Twitter. Journal of Pragmatics 191: 227–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trussel, John M., and Linda M. Parsons. 2007. Financial reporting factors affecting donations to charitable organizations. Advances in Accounting 23: 263–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Auwera, Johan, Volker Gast, and Jeroen Vanderbiesen. 2012. Human impersonal pronoun uses in English, Dutch and German. Leuvense Bijdragen 98: 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt, Mark, and Paul A. M. van Lange. 2006. The altruism puzzle: Psychological adaptations for prosocial behavior. In Evolution and Social Psychology. Edited by Mark Schaller, Jeffry A. Simpson and Douglas T. Kenrick. London: Psychology Press, pp. 237–61. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaert, Griet A., and Dirk Van den Poel. 2011. Empathy as added value in predicting donation behavior. Journal of Business Research 64: 1288–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismans, Roel. 2013. Address choice in Dutch 1: Variation and the role of domain. Dutch Crossing 37: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Gamze, and Kate G. Blackburn. 2022. How to ask for donations: A language perspective on online fundraising success. Atlantic Journal of Communication 30: 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Shubin, Liselot Hudders, and Verolien Cauberghe. 2017. Luxury brands in the digital era: A cross-cultural comparison of the effectiveness and underlying mechanisms of personalized advertising. In The Essence of Luxury: An Asian Market Perspective. Edited by Srinivas K. Reddy and Jin K. Han. Singapore: Center for Marketing Intelligence, pp. 126–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zemack-Rugar, Yael, Rebecca Rabino, Lisa A. Cavanaugh, and Gavan J. Fitzsimons. 2016. When donating is liberating: The role of product and consumer characteristics in the appeal of cause-related products. Journal of Consumer Psychology 26: 213–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemack-Rugar, Yael, Sarah G. Moore, and Gavan J. Fitzsimons. 2017. Just do it! Why committed consumers react negatively to assertive ads. Journal of Consumer Psychology 27: 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).