Abstract

There is little linguistic research on the structure of judicial opinions from a discourse analysis perspective. There are, however, many professional resources about writing judicial opinions. This paper contributes to genre theory and linguistics of languages for specific purposes by proposing a role for professional writing advice. We also construct a typology of macrostructures proposed by professionals and compare them to the move structure of authentic judicial opinions. Our results show that, in terms of large discourse units, professional resources and move analysis seem to converge. Professional resources, however, do not describe the variation that may be observed in authentic documents. In this way, corpora of professional advice may contribute to a deeper understanding of how a discourse community represents its own genres.

1. Introduction

“Does exploring the structure of opinions have any use?” (Leubsdorf 2002). In this article, we propose that it does. We agree that students of English for Legal Purposes (ELP) and legal professionals must have “at least an implicit understanding of this structure by learning to read an opinion as an opinion, rather than as some other kind of composition” (Leubsdorf 2002, p. 447). We also believe that linguistic analysis of these crucial documents is necessary for linguistics and for society. This paper is a first step toward these applied linguistic issues.

We are interested in judicial opinions in a common law system, and, in particular, in the decisions of the appellate and Supreme courts in the American judicial system. Regulators in the American federal and state systems do not advocate a universal format or structure. Kahn (2016, p. 5) reminds us that “it is not written anywhere that the court must issue an opinion; there are no rules requiring an opinion to take a certain form”, making this type of communication “an unexpectedly complicated and subtle genre” (Leubsdorf 2002, p. 451). Its complexity leads to a need for guidance in the legal community of practice. Hafner (2014), for example, has pointed out that novice lawyers (students) aspire to demonstrate their writing expertise in a specific professional legal genre by adapting the codes and rhetorical choices made by experts in the discourse community. Vance (2011) argues that the legal community of practice, both professional and academic, has attempted to bring guidelines to opinion writing, with recommendations in textbooks for professionals and in the creation of legal writing courses for students preparing for a career as a clerk and then a judge.

Nevertheless, few sources of professional advice cited deal with aspects of structuring and organizing information in an opinion (Vance 2011). Instead, they deal with issues of professional ethics and the context in which clerks and judges operate. When the sources do address the writing process, they deal mostly with issues of personal style (with an emphasis on “Plain English” recommendations), editing, or formatting. Hartig and Lu (2014, p. 88) summarize the issue as follows: “the majority of textbooks currently available on professional legal writing are not grounded in research-based descriptions of the genres that students are expected to produce”.

The exceptions to the aforementioned trend of focusing on lower-level language matters are rare. Maley (1985), writing from a legal perspective, made a pioneering prototype for opinion structure based on his analysis of a single judgment. He claimed that the generic elements of opinions followed the FIRCO structure: “Facts, F, an account of events and/or the relevant history of the case; Issues, I, either of fact or of law; Reasoning, R; Conclusion, C, the principle or rule declared applicable for the instant case, and Order or Finding, O” (Maley 1985, p. 160). Bhatia (1993), writing from a discourse analysis perspective, depicts a similar overall structure, but emphasizes the interaction between legally significant facts and applicable law when reaching legal conclusions in judgments. Cheng and Sin (2007) and Gozdz-Roszkowski (2020) adopt Swalesian move analysis (Swales 1990). The former compares American judicial opinions to Chinese opinions and finds the following moves: heading, summary, facts and issues in dispute, arguments/discussion, decision/conclusion. The latter studies the structure of judges’ justifications in the written decisions of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, finding the following moves: object of constitutional review and constitutional issue, evaluating the admissibility of application based on pre-established criteria, reconstructing standards of review, evaluating the (non)compliance of a normative act with the Constitution, and evaluating the effect of ruling. From a natural language processing perspective, Kalamkar et al. (2022) identify and annotate for twelve rhetorical roles in a corpus of Indian judicial opinions: preamble, facts, ruling by lower court, issues, argument by petitioner, argument by respondent, analysis, statute, precedent relied, precedent not relied, ratio of the decision, ruling by present court, and one neutral category.

Given these different types of literature, we ask three research questions: (1) what structure for judicial decisions do professional manuals about writing opinions propose?; (2) how does the structure of judicial decisions in a corpus annotated using Swalesian theory compare to the prescriptive descriptions found in professional manuals?; and (3) how is the professional literature integrated into genre theory?

This paper is structured as follows: first, we review the literature about genre theory and move analysis, about the general role of expert advice in genre theory, and about legal writing manuals more specifically; second, we present our methodology for analyzing a set of legal writing manuals and for annotating a sample of judicial decisions with Swalesian discourse analysis. We then compare the results of our analyses of the manuals and the corpus. We discuss our results in light of the literature, and we conclude.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.1.1. Genre Theory

Before examining sources of professional advice about how to write a judicial opinion, we survey the literature on writing from the genre analysis perspective. Much of this literature was originally motivated by attempts to teach composition in humanities programs or writing skills in the framework of language acquisition or language for specific purposes. Genre is a useful concept for teaching writing because it covers expectations about the form and content of an instance of communication, especially written communication. While genre has long been an object of reflection in studies of rhetoric and of literature, genre theory as a framework for analyzing language used in professional context developed more recently in what have been known as the Australian school, the American school, and the school related to language for specific purposes (LSP) to which Swalesian analysis belongs.

Each school places a different weight on the social or communicative function and on structure in its definition of genre. New Rhetoric, the American school, which renewed interest in classical approaches to rhetoric while introducing concepts from social sciences and pragmatics, emphasizes the functional nature of genres over the formal aspects (Miller 1984). Miller (1984) also famously defined genres as a “social action” in the title of her article. Miller (1984, p. 159) states that genres are “typified rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations”. Second, in systemic functional linguistics, the Australian school, there is also a focus on function, but it additionally highlights the importance of structure in defining genre as “staged goal-oriented social process” (Martin 2009). Third, in an LSP perspective, Swales (1990, p. 58) defines genre as “a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes. […] These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse community and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This rationale shapes the schematic structure of the discourse”. Swales’ definition focuses more clearly on structure as related to community expectations and is the most widely used genre framework. Legal language is also more prone to respect a given structure because of the risk of litigation if documents are deemed not to conform to standards (Hiltunen 2012). For this reason, we adopt a Swalesian approach to studying the structure of judicial opinions.

Swalesian discourse analysis (Swales 1990, 2004; Moreno and Swales 2018) allows for studying genre at a meso level, between the whole document level and the lexico-grammatical level. Swales (1990) developed the framework in order to teach students of English for academic purposes (EAP) to learn the smaller units involved in creating a research article. The units defined by Swalesian analysis are called moves and steps. Moves are more abstract units, defined as “discoursal or rhetorical units performing coherent communicative functions in texts” (Swales 2004, pp. 228–29). Steps are concrete in that they are “text fragments” (Moreno and Swales 2018, p. 40) that “primarily function to achieve the purpose of the move” (Connor et al. 2007, p. 24) to which they belong.

Move analysis provides a framework for studying how language interacts with social expectations in a community of experts at multiple levels of genre analysis. Researchers carrying out move analysis have highlighted that the analysis cannot uniquely rely on a corpus of specialized documents, but implies interaction with the professional community itself (Tarone et al. 1998). For this reason, Swalesian move analysis has integrated feedback from these experts in three ways (Moreno and Swales 2018). First, before undertaking a move analysis in a given professional field, professionals may be surveyed about the types of documents that are crucial to their work. Second, experts may be asked to provide examples of typical documents for a given genre. Third, experts may interact with analysts to validate the final annotation schemes proposed (Moreno and Swales 2018, p. 41) “given their deeper knowledge of the text subject matter and their stronger intuitions regarding the typical rhetorical structure and language used in good papers in their fields”. However, given that most of the literature using move analysis is published on research articles and, as such, the role of researcher and professional is not clearly distinguished, there is little research on how professional advice for producing written documents is treated in genre theory.

2.1.2. The Role of Expert Literature in Genre Theory

In short, we ask what role genre theory has reserved for expert advice in the form of manuals and articles rather than more spontaneous consultation of experts. As a pioneer in the analysis of legal discourse genres, Bhatia suggested that the study of legal genres should include a review of the related literature, and in particular professional literature (Bhatia 1993). However, increasing access to corpora of authentic legal documents has brought corpus-based studies on discourse to the forefront of genre studies. Our review of the scientific literature indicates that a comparison of professional literature to authentic corpora is lacking in English for Legal Purposes.

On one hand, existing literature focuses instead on what genre theory can bring to professionals in terms of instruction materials (Tribble 2009). This is, however, almost exclusively for students learning English for Academic Purposes (EAP). In this context, Tribble (2009) identifies three different traditions that EAP teachers use to teach writing to their learners. Particularly, Tribble (2009) identifies the “Social/Genre” tradition, which features analyzing texts and discourse of a specific genre through its structural and lexico-grammatical elements (move analysis). On the other hand, as pointed out by Hyland (2012): “unlike much of the academic writing research, however, a great deal of professional writing research has been motivated less by pedagogical concerns than by the desire to gain an understanding of how people communicate effectively and strategically in organizations” (Hyland 2012, p. 104). In other words, other than EAP, research results coming from genre theory are not directly informing professionals about writing; professional writing advice, in turn, is not generally informing genre theory, with the exception of research writing. Concerning research writing, Norman (2003) questioned the instructions found in scientific-style manuals, in particular the instructions recommending a uniform terminology to designate constant entities in the same text. His study of a corpus of authentic documents concluded that these instructions were respected. Yang and Pan (2023), again based on a corpus of authentic documents, determined that the recommendations concerning the use of informal elements in writing generally corresponded to writers’ practices.

The rift, with few exceptions, between professional writing advice and academic studies of specialized discourse is contradictory in the light of the importance of the concept of discourse community (Tribble 2015, p. 442) in genre theory. One of the scholars who adopts this term, Swales (1990, 2016), reminds us of the social nature of a discourse community, within which certain groups create or influence their own discursive practices as they develop conventions that meet their communication needs. Disciplinary experts are the most influential and attempt to direct communication to what they perceive as the needs of the discourse community. In return, novice members of the discourse community develop their writing expertise through their interaction with competent participants of the same community. Bhatia (2004, p. 165) highlights the high degree of interrelation between genre knowledge and what he defines as professional expertise, and asserts that the former “seems to be the key to pragmatic success in the use of language in wide-ranging professional contexts”. In this way, it is through the concept of discourse community that expert advice about genre production is integrated into the definition of a particular genre and, by extension, into the notion of genre itself.

However, none of the literature, in the American context, has attempted to compare the extensive advice given about legal writing, and, in particular, the writing of judicial opinions, to actual legal documents. This is perhaps because of the singular place that writing and written documents have in law. While it is assumed that the foundations of professional writing, be it letters, emails, reports, or formal speeches, are learned during secondary and higher education, it cannot be assumed that students know how to write a brief or a judicial opinion without specific training. The singularity of these genres, their importance, and their complexity has led to a corpus of professional advice on legal writing that has yet to be fully incorporated into genre theory. We survey some of the characteristics of this literature in the following section.

2.1.3. Manuals

Manuals and professional articles, as argued in the previous section, can be viewed as a part of specialized communication, written by professional experts for professional novices with the objective of sharing their genre knowledge of the judicial opinion. Since their pragmatic aim is to ‘tell how to do’ in the course of a succession of obligatory or optional steps, they can be classified as procedural or instructional texts. Adam (2001) identifies several non-exclusive subsets under this umbrella name:

- Regulatory texts, which aim to regulate the behavior of one or more individuals;

- Programmer texts, where a speaker–programmer who is competent in a domain transfers their know-how to a reader–actor through the description of a process to be executed;

- Instructional–prescriptive texts that directly prompt action;

- The injunctive–instructional texts, similar to the previous ones in that they set up injunctive instructions;

- Advisory texts;

- Receipt texts.

According to Aouladomar and Saint-Dizier (2005), procedural texts use arguments based on the principles of rhetoric to convince the addressee to perform the prescribed actions. These texts, therefore, appeal to concepts of logic, but also to the emotions of their readers.

To sum up our literature review, we find three gaps in the literature about specialized genres, especially legal genres. First, the role of professional advice in the form of manuals is not well-defined in genre analysis. Second, there is no summary, neither in the legal nor in the linguistic literature about the overall structure proposed by the manuals and professional articles. Thirdly, a comparison between professional writing resources and an academic study of American judicial opinions is lacking. We propose a methodology for answering these questions in the following section.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Manuals

For the analysis, we selected eleven different sources, based on their relevance and accessibility. Out of the 45 resources for judicial writing presented by Vance (2011), we collected those that were either available online or in French libraries. We then excluded the sources that did not provide recommendations or information on the actual or advisable structure of judicial opinions. In the end, seven resources presented by Vance (2011) were integrated into our analysis. These include two journal articles, two manuals for professionals, and three books addressing issues of legal writing and opinion writing. Besides Vance’s (2011) sources, our own review of the existing literature about judicial writing led us to analyze three additional documents: three books intended to facilitate lawyers’ understanding of judges’ opinions. The sources we analyzed mostly concern appellate opinions in the US judicial system, although some of them are more general and include district court opinions, while one of them is more specific and addresses the question of Supreme Court opinions. Table 1, below, offers an overview of the sources and a more detailed description of manuals and articles reviewed can be found in Appendix A:

Table 1.

Overview of the judicial manuals under study.

As mentioned in our introduction, our purpose is to compare the move structure of judicial opinions to the structure that is described and recommended in the resources created by the legal community. However, legal professionals do not describe legal opinions in terms of moves. The nature of the structure and linguistic observations put forth by the legal community about the communicative features of judicial opinions is heterogenic. Therefore, we will not refer to the categories established in our exploration of the professional literature as moves or steps. Instead, we use the term macro-divisions; these are defined using 1–5 below. We establish an inventory of potential macro-divisions as described by the resources about judicial opinion writing.

To establish this inventory, we used the following methodology:

- In the manuals, we identified sections that indicate a description of the outline, the format, or the structure that opinions usually have or should have;

- Within these sections, each specific feature described in at least one of the sources was then considered a potential macro-division of a judicial opinion;

- After examining all the resources, we then counted the number of occurrences of a potential macro-division;

- Additionally, we found lower level divisions inside the macro-divisions identified in phase 2 of our methodology. For example, some of the sources simply propose that opinions include a section in which the court justifies the final decision without giving details about its content. Others provide details about the stages involved in the justification (see Figure A1 for examples);

- Before presenting the results of this exploration, we classified our sources according to different analytic criteria: descriptive/prescriptive, author’s expertise, target audience, and level of detail.

Our overview of the sources led us to classify the macro-division into different groups. First, we carried out an analysis of the macro-divisions that we found in sources with a low level of detail and then to those found in sources with a high level of detail. Sources with a low level of detail offer only very brief descriptions of the communicative features that should make up a judicial opinion, usually in one page or even less for the whole account of the structure of a judicial opinion. Sources with a high level detail offer longer descriptions of the divisions, usually, more than three pages. When a macro-division was present in all or virtually all the sources of a group, we also provided the position in which their author said they appear or should appear in a judicial opinion. One exception was the source “The Structure of Judicial Opinions”, which does not explicitly state the order of appearance of the opinion’s main elements.

The authors’ expertise criterion seemed to correlate with the descriptive/prescriptive criterion. For this reason, we then compared the macro-divisions of the source group Judges vs. the group Scholar. This distinction reflects the possible different views towards the structure of the judicial opinion within the legal community.

2.2.2. Move Analysis

The move analysis was carried out on a sample corpus of Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) majority opinions. We describe the two phases of annotations and the construction of a representative corpus in the following paragraphs.

The annotation took place in two phases. In the first phase, we based our methodology on Moreno and Swales’s (2018) move analysis of the discussion section of research articles. In this, steps are annotated based on functional rather than formal criteria: “A step is a text fragment containing ‘new propositional meaning’ from which a specific communicative function can be inferred ‘at a low level of generalization by a competent reader of the genre’” (Moreno and Swales 2018, p. 49). As per its linguistic instantiation, “[a] step can be realised by a proposition, a proposition complex or an even larger fragment of text”. (Moreno and Swales 2018, p. 48). However, because the annotations are part of a larger project (Lexhnology ANR-22-CE38-0004) that includes machine learning, we first had to impose a clear and coherent segmentation based on formal units. We chose the unit of a grammatical sentence. We assigned a communicative function, a step, to each unit.

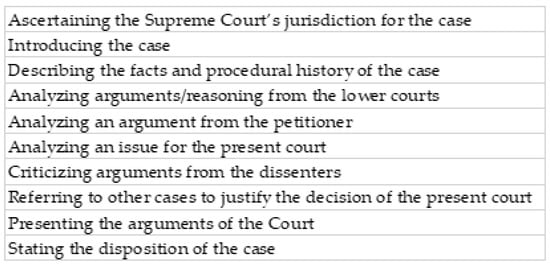

For the annotation itself, we used the free annotation software Taguette (Rampin and Rampin 2018) to carry out an exploratory study of 5 historical landmark opinions in SCOTUS case law (see Appendix B). We annotated a shared version of each opinion. This phase resulted in more than 100 steps for the 5 opinions. Following Moreno and Swales (2018), we also proposed 10 prototypical moves (see Figure A3 in Appendix B) based on observations of patterns in some of the opinions, on the manuals, and on how we thought the moves should logically be constituted. We especially focused on transitions that signaled the openings and closings.

We then decided to test the moves and steps from the first phase on a more representative corpus of SCOTUS majority opinions. The corpus was constructed by consortium partners in Lexhnology (see Acknowledgements for details). We used the SCOTUS Opinions (Fiddler 2020) corpus available online. SCOTUS Opinions was itself taken from the website Court Listener (CourtListener 2024) and enriched with metadata about the cases. As majority opinions are long and the annotation process is complicated, we wanted to create a sample corpus with the smallest number of opinions that would optimize representativity in terms of date, length, and theme. We, therefore, created a representative corpus for the majority opinions from 1945 to 2020 using two criteria: the justice listed as author of the majority opinion and theme. Author was chosen because this variable covers the variation linked to date and length of the opinions. As for the themes, they were constructed with a K-means clustering algorithm (K = 18) using term frequency * inverse document frequency. This process allowed us to group our data into thematic homogeneous groups, resulting in 18 different themes. Finally, we chose a threshold of the first 4 most productive justices for each theme, as this gave us the best representativity for the smallest number of opinions. The total number of opinions in the sample corpus was 18.

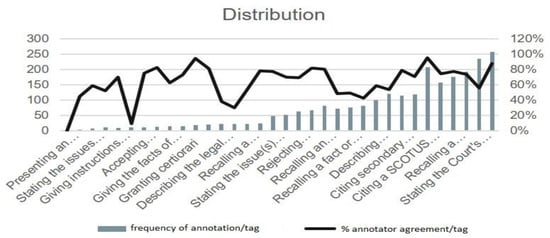

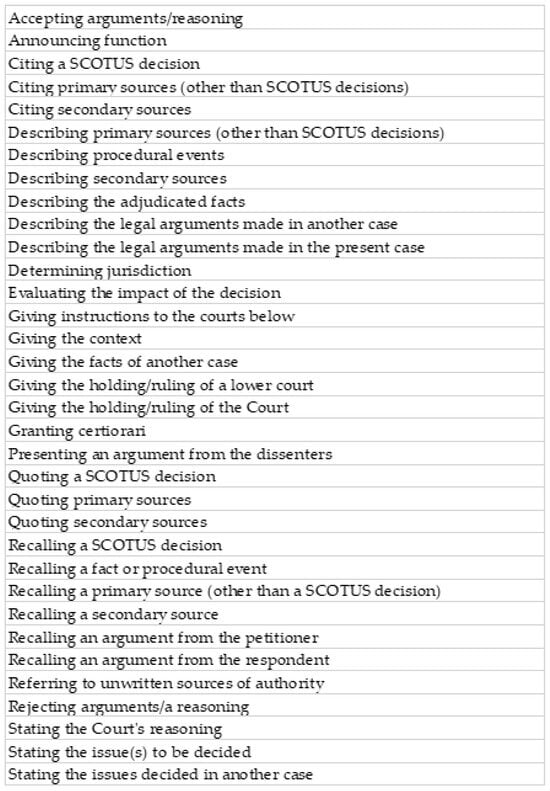

This representative corpus was used in the second phase of annotation. We tagged the full sample of 18 opinions described in the preceding paragraph. Each opinion was annotated separately by one of the authors of this article without consultation. After each opinion was annotated, we then discussed each segment to resolve differences in annotation. At the end of this process, we reduced the initial list of more than 100 steps to 34 steps (see Figure A4 in Appendix B). These were validated by an external legal expert. All 18 opinions were reannotated with the final set of annotations. The current Cohen’s Kappa for the annotation scheme and process is 0.66, which indicates that we have achieved a good level of coherence when we annotate the same opinion separately. In terms of distribution, Figure 1 below shows the percentage of annotation agreement between the two annotators on the left. On the right, Figure 1 shows how frequently an annotation appears. To give a few examples, some annotations, such as granting certiorari are infrequent because they appear only once in each opinion; however, they contain fixed language and are easy to identify. Other annotations, such as recalling a SCOTUS opinion, appear frequently, but are more difficult to identify because they are more closely related to other interpretation annotations, such as stating the Court’s reasoning.

Figure 1.

Percentage of annotator agreement according to frequency of individual annotation.

The frequency of appearance per annotation was obtained by counting the number of occurrences of each annotation for each annotator. We then harmonized these results by averaging the appearance frequencies per annotation for each annotator. The annotator agreement per annotation was obtained by counting the number of times both annotators had chosen to annotate the same segment with the annotation in question. This number was then divided by the number of occurrences of the annotation by each annotator. We then harmonized these results by averaging the annotator agreements per annotation and per annotator.

Importantly, the prototypical moves identified in the first annotation phase did not appear in the representative sample. This points to wide variation of SCOTUS opinions in terms of larger discourse units. We plan to investigate the move level of macro-divisions in a later study using machine learning to identify regular patterns of steps. For this paper, however, our corpus-based study focused on the steps that were manually annotated. This choice is in line with the methodology proposed by Moreno and Swales (2018, p. 44), who conclude after reviewing the move analysis literature that “steps may be better indicators of shared psychological realities than moves and that annotating […] sections for their steps before conceptualising the moves might help us to arrive at a clearer picture of what is happening […]”. In our methodology, the steps were then compared to the macro-divisions found in the expert literature.

3. Results

3.1. Manuals

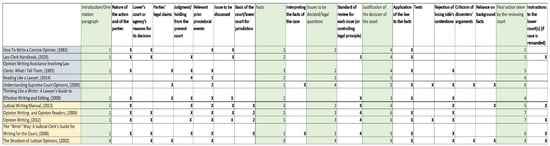

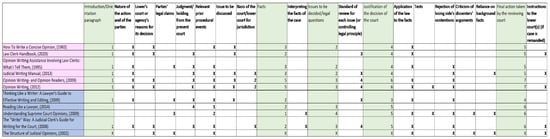

A summary of our analyses of the manuals is presented in Figure A1 and Figure A2 (see Appendix A), which indicate each source in the left-hand column, the presence or absence of the rhetorical divisions identified from that same source or from others included in our scope of research. Figure A1 separates the sources that evoke the structure of judicial decisions in detail from those that do not enter into detail. Figure A2 separates sources written by judges from those written by academics.

The figures show that five macro-divisions are found in almost all the sources analyzed:

- Introduction/Orientation Paragraph(s);

- Facts;

- Issues to be decided/legal questions;

- Justification of the decision of the court;

- Final action taken by the reviewing court.

In particular, for sources with a low level of detail, these divisions are sometimes the only structure cited by the experts. For example, Justice Charles Douglas (1983, pp. 4–6) describes them as the “five constituent parts of an opinion”, without developing their content further other than in a few sentences about the introduction, which he describes as follows: “the nature of the action and how it got to the appellate court”. These divisions echo the FIRCO structure proposed by Maley (1985). However, our observations highlight the almost systematic presence of a section introducing the opinions. In addition, we note that while the concluding part of the opinions (‘Final action taken by the reviewing court’) seems to omit the letter O of Maley’s model, in reality, when we look at sources that are more generous in their descriptions or recommendations, we notice that the announcement of the judgment is often followed by instructions to the lower courts, particularly when the case is remanded. This shows a fit with the FIRCO model.

Thus, according to legal professionals, the five main divisions seem to represent the backbone of any judicial decision. This also echoes the Greco-Roman model of the art of persuasive rhetoric presented by Aldisert (2012):

- Exordium, i.e., the introduction that presents the major questions of the case (How? What? Who? When? Where?);

- Divisio, or the announcement of the division of the case according to the legal issues to be discussed;

- Narratio, the recounting of the facts of the case;

- Confirmatio, i.e., the presentation of evidence to analyze the parties’ arguments on the points of law;

- Peroratio, the final legal conclusion of the case.

According to Aldisert et al., “these five parts form the structure of every well written opinion. Each is absolutely essential” (Aldisert et al. 2009, p. 24). As these parts are found in almost all the sources analyzed, we were also able to compare their order of appearance in the texts according to their authors. This analysis is of interest only for the intermediate parts, but it shows that there is no consensus on the question of presenting facts before legal issues. Indeed, excluding Leubsdorf’s (2002) article, for which the order of divisions is omitted, facts are presented before legal issues in half the sources observed. This quotation from Aldisert et al. (2009) may shed some light on divergent points of view: “The statement of issues usually should precede the narration of the facts. [...] This does not mean that the statement of issues must always precede the statement of facts in the final draft of the opinion. That may depend on style” (Aldisert et al. 2009, p. 28).

This is, therefore, a matter of personal preference, and may also depend on the type of case. In some highly procedural cases, the facts in dispute are the very problem to be solved. Thus, some authors do not attribute a formal rule to this question, and speak of conventions that evolve over time. For McKinney (2014, p. 23), the presentation of legal issues must take place “someplace in the opinion”. Within the lower level divisions, only the introduction/orientation paragraphs and justification of the decision of the Court sections are the subject of significant clarification regarding their content. The legal professionals emphasize the role of the introductory paragraphs in setting the scene, focusing above all on the presentation of the parties and the procedural elements that led to the trial before the adjudicating court. Most authors also emphasize the introductory section’s function of anticipating information, which they believe should announce the legal issue and the final judgment before they are repeated later in the opinion.

The justification section, on the other hand, contains few elements, according to the sources studied, which indicate that the section must apply the law to the facts. It should be noted, however, that the high-level sources systematically include an assessment and then a rejection of the losing party’s claims and arguments in the present case.

Finally, a comparison of the sources written by judges and those written by scholars reveals that they differ above all in the introduction. Judges attach greater importance to this part, and, thus, recommend that the parties to the case be precisely identified. The anticipatory function of the introduction is also widely emphasized by the judges, who clearly distinguish themselves from the scholars by recommending that both the legal problem and the final judgment be announced in the very first lines of the opinion.

3.2. Move Analysis

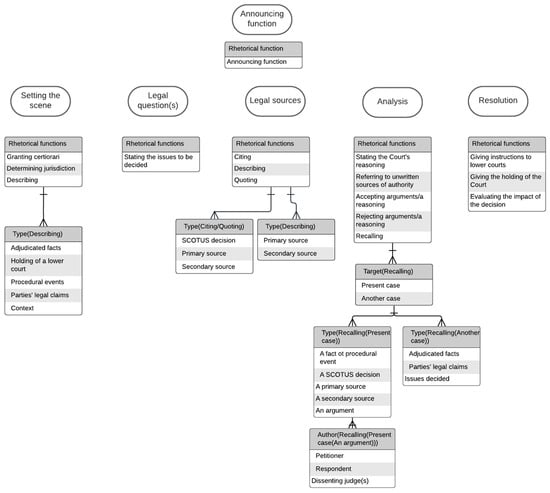

As compared to the analysis of manuals, the move analysis shows that SCOTUS opinions vary widely in their structure. We grouped the 34 finalized step annotations (see Appendix B, Figure A4) into the categories shown in Figure 2 (below). It is important to emphasize that the categories are not moves, but a classification of types of steps: indeed, we believe that moves are situated at an intermediate level between the step-level and the category-level. Other differences also exist. The categories legal question(s) and legal sources are thematic rather than communicative. They are, thus, likely to appear throughout the text, interspersed amongst steps pertaining to another category. Furthermore, a third category, which is metadiscursive (announcing function), contains only one step and also appears throughout the text. The three remaining categories represent broad communicative functions. They are analogous to sections of research articles, i.e., introduction, literature, methods, etc. These are broad and very long sections that are generally considered to be at a higher level of discourse than moves in Swalesian analysis.

Figure 2.

Categorization of steps.

The typology includes five larger categories:

- Setting the scene: the Court’s decisions usually consist of introductory paragraphs that serve to introduce the case to the reader. They, therefore, contain elements relating to the nature of the parties, their claims in the case, the material facts concerning them, and the course of the proceedings that led the Court to rule on the case as final jurisdiction;

- Legal questions: the indication of the legal issue to be resolved by the Court generally comes at the end of the setting of the case. However, we have placed it in a separate category, since we have found that it can also be stated several times in the opinion, sometimes in ways that broaden or narrow the issue;

- Legal sources: we have also placed sources of law in a separate category. Indeed, many sources of law, whether case law, legislation, or the Constitution, appear throughout the opinions. Sometimes, the judges clearly highlight a section in their opinion that describes the sources of law that will be discussed in the analysis section. However, whenever sources of law are evoked in support of the judges’ arguments, we consider that they should be associated with the rhetorical functions of the analysis section;

- Analysis: this category corresponds to the heart of SCOTUS opinions. It is generally the longest, beginning after the expository part and ending before the statement of the final decision. The text is argumentative in nature, and includes the Court’s justification in response to the parties’ arguments;

- Resolution: this section reports on the resolution of the legal problem of the case by stating the final decision, following the argument of the majority. If the final judgment is mandatory, it may sometimes be accompanied by instructions for the lower courts and/or considerations of the impact of the decision on civil society.

In terms of the overall order in which the steps appear, some appear in a relatively fixed position in the text. In general, steps that appear in the category setting the scene appear first, followed by those in the analysis, and finally, resolution. Other steps, however, appear throughout the opinion. These include the metadiscursive step announcing function, the issue, and the steps related to dealing with other sources. Crucially, the largest number of steps relate to the analysis of the justices. They also represent the largest part of the opinions.

The annotation process and final annotation scheme make it clear that the macro-divisions proposed by the manuals and professional articles are not on the same level as steps. Overall, the macro-divisions proposed by professionals are based on long-standing rhetorical divisions that are larger than steps. Nor are they moves, as moves had not yet emerged from the representative sample corpus. This is because there is wide variation in how the steps appear in opinions in the sample corpus. We also did not find clear transitions that would open and close moves in the sample corpus. We discuss our findings in detail in the following section.

4. Discussion

Our study contributes to the conversation about the role of expert advice in language for specific purposes. We structure this discussion around our three research questions, starting from the most concrete and moving to the more theoretical.

4.1. The Structure of Judicial Decisions According to Professional Manuals

The macro-divisions in the manuals include introduction, facts, issues, reasoning, and final decision. These divisions are similar to the divisions observed by some researchers, such as Bhatia (1993). According to Aldisert (2009), this organization is highly influenced by classical rhetoric studies.

4.2. Comparison of Professional Manuals and Authentic Documents

We also investigate how the content of professional manuals compares with authentic documents. These questions are relatively new to the disciplinary framework of legal English, despite Bhatia’s (1993) earlier recommendations to carry out such comparisons. While this study is the first to adopt Bhatia’s (1993) suggestions for legal English, such a comparison exists in other specialized domains at a microlevel, as shown by the studies of Norman (2003) and Yang and Pan (2023) who found that expert advice was coherent with what was found in authentic scientific writing. As compared to the studies mentioned, we study a higher level of discourse and legal language. In our study of judicial opinions, the divisions we observe in prescriptions or descriptions in professional writing advice sometimes also correspond to those in the corpus of judicial opinions. In our corpus, we observe categories of steps that are similar to the five categories identified in the majority of manuals: setting the scene in our corpus study is similar to introduction in the manuals; analysis is similar to reasoning; and resolution is similar to final decision. These sections generally appear in the same order, in the professional manuals, academic research (Bhatia 1993; Kalamkar et al. 2022), and in our corpus study. Furthermore, issue is identified in all of these studies. Our study shows, however, that this division does not always appear in the same place.

One major difference in our corpus study is that we carry out an analysis at a lower level of discourse. At step level, for example, we find a variety of text fragments related to dealing with different “sources of discourse”. This level of precision is not found in most manuals. The manuals, therefore, do not include the wide range of units and discourse strategies used to build the legal opinions, for example the variety of steps in the analysis category identified during our move analysis. In addition, the manuals present judicial opinions as having a stable structure. In a similar vein, the recommendations set out in the manuals are deliberately vague.

Legal professionals’ effort to link the Aristotelian rhetorical model to the structure of opinions may be aimed at demonstrating continuity with accepted models of persuasion. According to this reasoning, accepted models may be legitimately reproduced and, as a consequence, are generally observed in legal opinions. In addition, by arguing that opinion writing is based on ancient and immutable rhetorical principles, legal professionals may avoid giving the impression that legal decisions are arbitrary.

The findings of this study, however, contradict the representation of SCOTUS opinions as uniform and stable. Instead, they suggest that the structure of SCOTUS opinions is highly variable. For example, no moves can currently be constructed from the steps because full annotation will be necessary to recognize, possibly with the help of machine learning, patterns of steps. This variation may be explained by the fact that there is no ready-made answer to justify a legal decision in the United States. The legal cases handled by American courts are highly diverse, and this diversity of legal facts necessarily calls for a tailor-made response from judges. It can also be seen as a desire to leave the field of interpretation open. According to Black et al. (2016), SCOTUS justices alter their opinion writing to improve compliance and to increase the general public’s acceptance of their decisions. The same idea of strategic writing can be applied to communicative structure.

In sum, what characterizes SCOTUS decisions is the relative freedom to deploy arguments to achieve varying communicative purposes. A highly elaborate and standard framework for opinion-writing would reduce this freedom, especially because all American justices and judges do not necessarily adhere to the same school of legal theory or target the same audience members. SCOTUS opinions, for example, may be different from the opinions of lower appellate courts because SCOTUS opinions are covered by the press. SCOTUS justices also tend to have a distinct style, which may introduce even more variation into the structure of the opinions.

4.3. Contributions to Move Analysis and Genre Theory

Our study contributes nuances to move analysis and genre theory. We find that the divisions we observe in the opinions are more cyclical than moves in scientific articles. Discourse in case law is based on constructing logical arguments using different sources of discourse. Scientific articles, on the contrary, construct a more linear argument that clearly ‘moves’ in one direction. The popularity of the model developed by Swales lies in its ability to account for discursive configurations inherent to a given genre. These configurations are not immutable, however, and when they are applicable, which is not always the case (see Maswana et al. (2015) in the hard sciences, and Lu et al. (2021) for the social sciences), they can be modified according to the needs of the writer.

Our corpus-based study of macro-divisions in SCOTUS opinions reveals that linear progression does not always match how judges write opinions. At the step level, we found cyclical movements based on interdiscursivity and intertextuality. Indeed, to support their arguments, judges often call on external sources of law, on their own discourse set out earlier in the judgment, or on the arguments of the losing party in order to reject them. This intermingling of external sources of discourse tends to disrupt the communicative unity of the judges’ argument and the linear trajectory of the discourse’s main thread. In some cases, such as Baldwin v. Reese (2004), the cyclical dimension of the discourse is explicitly present, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Example of cyclical distribution of Analysis steps in Baldwin v. Reese (2004).

Finally, we contribute to genre analysis by questioning the role of expert advice in studying genre. Our literature review and our studies show that (1) expert advice does not completely deviate from the structure of authentic corpora; (2) when there are a number of sources of expert advice, such as about opinion writing, they tend to converge; (3) expert advice tends to present a simplified representation of the documents described. For example, the variation we observe in the structure of SCOTUS opinions is not addressed in the manuals; (4) this may be motivated by the desire to give non-members of the discourse community the impression that the production of judicial opinions is unified and, thus, controlled, whereas, in practice, the lack of constraints about opinion writing give justices large margins of freedom to adopt variable patterns of justification; (5) expert advice in opinion writing tends to integrate traditions from larger persuasive language, such as Greco-Roman models; (6) expert advice on language should be a more prevalent object of study for linguistics and language for specific purposes. While this discourse does not represent the complexity of authentic corpora, collections of expert advice contribute to a discourse community’s auto representation, which contributes nuance to genre analysis. They are also sources for studying interaction between a given specialized language and less specialized language, as the references to Greco-Roman rhetoric show in legal argumentation.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to a richer vision of specialized genres and language, in which expert advice is both an additional source of information about specialized discourse and an object of study itself. Much research remains to be done, both on legal expert advice and on the opinions itself. One future perspective for genre research that our findings highlight is the representation of genres by their own discourse communities. In the case of SCOTUS majority opinions, this aspect may be further researched once the annotation of the full corpus has been achieved. The full annotation will allow for a closer observation of trends of step organization and move construction. Interviews with American judges and other legal professionals may allow for comparing current perceptions of the discourse community about the structure of majority opinions with their actual structure. Future studies may include investigating courses about writing or reading judicial opinions. For the time being, however, the present study points to the complimentary information that may be found by analyzing both the professional literature about majority opinions and our corpus of SCOTUS opinions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.L.; methodology, M.C.L. and W.B.; validation, M.C.L.; formal analysis, M.C.L. and W.B.; investigation, M.C.L. and W.B.; resources, M.C.L. and W.B.; data curation, M.C.L. and W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.L. and W.B.; writing—review and editing, M.C.L. and W.B.; visualization, M.C.L. and W.B.; supervision, M.C.L.; project administration, M.C.L.; funding acquisition, M.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agence Nationale De Recherche, grant number ANR-22-CE38-0004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because the research is ongoing.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of Nicolas Hernandez and Anas Belfathi (Nantes Université, LS2N, UMR 6004, F-44000 Nantes, France) in preparing the representative sample corpus of the SCOTUS Opinions corpus.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Aldisert (2012) and Aldisert et al. (2009): two of the sources are written by judge Ruggero J. Aldisert. At the time of publication, he was an appellate judge in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. The first source is a monograph entitled Opinion Writing (Aldisert 2012). It provides guidance for professionals who aim to learn or to perfect their opinion writing. The second source by Aldisert is an article entitled “Opinion Writing and Opinion Readers” (Aldisert et al. 2009). It draws on the topics presented in the second edition of Opinion Writing “while specifically highlighting the relationship between opinion writing and opinion readers” (Aldisert et al. 2009, p. 4). These two sources offer the most detailed description of the structure of an opinion in terms of macro-divisions. Opinion Writing has an entire section dedicated to the “Anatomy of an Opinion”, while “Opinion Writing and Opinion Readers” intends to “dissect the ideal structure of an opinion” (Aldisert et al. 2009, p. 4). These sources, thus, adopt a prescriptive view towards the professional community of judges and law clerks. They are based on the author’s 30-year experience as an appellate judge.

- Douglas (1983): “How to write a concise opinion” (Douglas 1983) is a short article written by appellate judge Charles G. Douglas. It was published in the Judges Journal, suggesting a readership composed of a majority of judges. It adopts a very prescriptive view on how judges should write their opinion in order to reduce its length.

- Federal Judicial Center (2013, 2020): the handbooks Law Clerk Handbook and Judicial Writing Manual are comparable in that they are intended as manuals for professionals. Both are written by the same judicial agency, the Federal Judicial Center. They provide an overview of legal professionals’ specific duties with a chapter focusing on research and legal writing. These two sources are prescriptive and provide the same type of guidance. Judicial Writing Manual, however, offers a more detailed view of the structure that an opinion should have.

- Klein (1995): “Opinion Writing Assistance Involving Law Clerks” is an article written by judge Richard B. Klein. It specifically addresses law clerks and recommends guidelines to improve their opinion writing. These recommendations are drawn from Klein’s own experience as a judge, as they “fit his personal style” (Klein 1995, p. 7). The article is relatively detailed and comments on lower levels of language as well.

- Sheppard (2008): “The ‘Write’ Way: A Judicial Clerk’s Guide to Writing for the Court” is an article written by Jennifer Sheppard and published in the University of Baltimore Law Review. Jennifer Sheppard is an Assistant Law Professor at Mercer University School of Law. She addresses law clerks and law students and offers a fairly detailed approach to writing an opinion. Her article is both descriptive and prescriptive as regards to format. She presents excerpts from actual opinions and guidelines to clerks, based on what an opinion generally includes. Her description is not, however, informed by an identified corpus of opinions. Importantly, she states that “the format of an opinion may vary depending on the court or the case itself” (Sheppard 2008, p. 79).

- Armstrong and Terrell (2009): Thinking like a Writer: a Lawyer’s guide to effective writing and editing has only a short section about judicial opinion writing. The rest of the book presents a large set of principles and tips that lawyers should use to improve their legal writing in general. These same principles are used to describe “the structure of a simple opinion” (Armstrong and Terrell 2009, p. 259). The description of macro-divisions is based on what the authors, drawing on their experience, consider logical and coherent for a judicial opinion.

- van Geel (2009): Understanding Supreme Court Opinions is a book intended for law students. Its author, T.R. Van Geel (professor of law and political science), says that it should supplement their constitutional casebook material. The audience can also include lawyers who wish to improve their understanding of SCOTUS opinions. The book adopts a descriptive approach. The organizational structure is referred to in terms of the most typical elements shared among Court’s opinions.

- McKinney (2014): The book Reading Like a Lawyer was written by the law professor Ruth Ann McKinney. As the title suggests, its target audience is lawyers who want to improve their strategies for reading case law. The book includes a brief description of the structure of a judicial opinion, based on “conventions that have evolved over time” (McKinney 2014, p. 23). No further detail about the macro-divisions is given.

- Leubsdorf (2002): “The Structure of Judicial Opinions” takes a linguistic perspective when describing judicial opinions. This distinguishes the long article from the other sources studied in this article. Its author, law professor John Leubsdorf, describes these documents being examples of a complex genre that intertwines different voices and stories. Although it includes the main elements of an opinion in detail, the piece does not explicitly state how the information is organized within these elements, nor does Leubsdorf present the order in which law students or lawyers are expected to encounter the information within the main elements. Like most of the professional sources, Leubsdorf’s analysis relies on his own practice and experience as a law practitioner.

Additional Information about the Expert Sources under Study

Figure A1.

Candidate macro-divisions (in green) and micro-divisions: high level of detail (in grey) vs. low level of detail (in yellow) in the sources under study.

Figure A2.

Candidate macro-divisions (in green) and micro-divisions depending on author’s expertise (judges in pink, scholars in blue).

Appendix B

Figure A3.

Ten prototypical moves from first phase of annotation.

Figure A4.

Final set of step annotations after the second phase of annotation.

References

- Adam, Jean-Michel. 2001. Types de textes ou genres de discours? Comment classer les textes qui disent de et comment faire? Langages 35: 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldisert, Ruggero J. 2009. Opinion Writing, 2nd ed. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. [Google Scholar]

- Aldisert, Ruggero J. 2012. Opinion Writing, 3rd ed. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldisert, Ruggero J., Meehan Rasch, and Matthew P. Bartlett. 2009. Opinion Writing and Opinion Readers. Cardozo Law Review 31: 43. [Google Scholar]

- Aouladomar, Farida, and Patrick Saint-Dizier. 2005. Towards Generating Procedural Texts: An Exploration of Their Rhetorical and Argumentative Structure. Paper present at the Tenth European Workshop on Natural Language Generation (ENLG-05), Aberdeen, UK, August 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Stephen V., and Timothy P. Terrell. 2009. Thinking Like a Writer: A Lawyer’s Guide to Writing and Editing, 3rd ed. New York: Practsising Law Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin v. Reese. 2004. 541 US 27. Washington, DC: U.S. Supreme Court Center.

- Bhatia, Vijay K. 1993. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, Vijay K. 2004. Worlds of Written Discourse: A Genre-Based View. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Ryan C., Ryan J. Owens, Justin Wedeking, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2016. U.S. Supreme Court Opinions and Their Audiences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Le, and King-kui Sin. 2007. Contrastive Analysis of Chinese and American Court Judgments. In Language and the Law: International Outlooks. Edited by Krzysztof Kredens and Stanislaw Goźdź-Roszkowski. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 325–56. Available online: https://www.peterlang.com/view/title/51172 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Connor, Ulla, Thomas A. Upton, and Budsaba Kanoksilapatham. 2007. Introduction to move analysis. In Discourse on the Move: Using Corpus Analysis to Describe Discourse Structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 28, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- CourtListener. 2024. Available online: https://www.courtlistener.com/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Douglas, Charles G. 1983. How to Write a Concise Opinion. Judges Journal 22: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Judicial Center. 2013. Judicial Writing Manual, A Pocket Guide for Judges, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Federal Judicial Center. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Judicial Center. 2020. Law Clerk Handbook, 4th ed. Traverse City: Independently Published. [Google Scholar]

- Fiddler, Garrett. 2020. SCOTUS Opinions. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/gqfiddler/scotus-opinions (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Gozdz-Roszkowski, Stanislaw. 2020. Move Analysis of Legal Justifications in Constitutional Tribunal Judgments in Poland: What They Share and What They Do Not. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 33: 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, Christoph A. 2014. Professional Communication in the Legal Domain. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Professional Communication. London: Routledge, pp. 349–62. Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/chapters/edit/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9781315851686-29&type=chapterpdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Hartig, Alissa J., and Xiaofei Lu. 2014. Plain English and Legal Writing: Comparing Expert and Novice Writers. English for Specific Purposes 33: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiltunen, Risto. 2012. The Grammar And Structure Of Legal Texts. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, Ken. 2012. ESP and Writing. In The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes, 1st ed. Edited by Brian Paltridge and Sue Starfield. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Paul W. 2016. Making the Case: The Art of the Judicial Opinion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamkar, Prathamesh, Aman Tiwari, Astha Agarwal, Saurabh Karn, Smita Gupta, Vivek Raghavan, and Ashutosh Modi. 2022. Corpus for Automatic Structuring of Legal Documents. arXiv arXiv:2201.13125. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Richard B. 1995. OPINION WRITING ASSISTANCE INVOLVING LAW CLERKS: WHAT I TELL THEM. Judges’ Journal 34: 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Leubsdorf, John. 2002. The Structure of Judicial Opinions. Minnesota Law Review 86: 447–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Xiaofei, Jungwan Yoon, and Olesya Kisselev. 2021. Matching Phrase-Frames to Rhetorical Moves in Social Science Research Article Introductions. English for Specific Purposes 61: 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maley, Yon. 1985. Judicial Discourse: The Case of the Legal Judgment. Beiträge Zur Phonetik Und Linguistik 48: 159–73. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, James R. 2009. Genre and Language Learning: A Social Semiotic Perspective. Linguistics and Education 20: 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maswana, Sayako, Toshiyuki Kanamaru, and Akira Tajino. 2015. Move Analysis of Research Articles across Five Engineering Fields: What They Share and What They Do Not. Ampersand 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, Ruth Ann. 2014. Reading like a Lawyer, 2nd ed. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Carolyn R. 1984. Genre as Social Action. Quarterly Journal of Speech 70: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Ana, and John Swales. 2018. Strengthening Move Analysis Methodology towards Bridging the Function-Form Gap. English for Specific Purposes 50: 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Guy J. 2003. Consistent Naming in Scientific Writing: Sound Advice or Shibboleth? English for Specific Purposes 22: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampin, Rémi, and Vicky Rampin. 2018. Taguette: Open-Source Qualitative Data Analysis. Journal of Open Source Software 6: 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Jennifer. 2008. The ‘Write’ Way: A Judicial Clerk’s Guide to Writing for the Court. University of Baltimore Law Review 38: 73. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, John. 1990. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, John. 2004. Research Genres: Explorations and Applications. Cambridge Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swales, John. 2016. Reflections on the Concept of Discourse Community. La Revue Du GERAS ASP 69: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarone, Elaine, Sharon Dwyer, Susan Gillette, and Vincent Icke. 1998. On the Use of the Passive and Active Voice in Astrophysics Journal Papers: With Extensions to Other Languages and Other Fields. English for Specific Purposes 17: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribble, Christopher. 2009. Writing Academic English—A Survey Review of Current Published Resources. ELT Journal 63: 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribble, Christopher. 2015. Writing Academic English Further along the Road. What Is Happening Now in EAP Writing Instruction? Elt Journal 69: 442–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, Tyll. 2009. Understanding Supreme Court Opinions, 6th ed. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, Ruth C. 2011. Judicial Opinion Writing: An Annotated Bibliography. Legal Writing Inst. 17: 197. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yiying, and Fan Pan. 2023. Informal Features in English Academic Writing: Mismatch between Prescriptive Advice and Actual Practice. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 41: 102–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).