The History of -eer in English: Suffix Competition or Symbiosis?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Aims

2.1. Competition and Symbiosis: Theoretical Background

The over-arching property that governs both blocking and elsewhere distribution is competitive exclusion. This top-down property of languages and of all self-organizing systems makes it difficult (though not impossible) for any two morphological patterns or two words to occupy the same niche. Given enough time, one will oust the other.(p. 60)

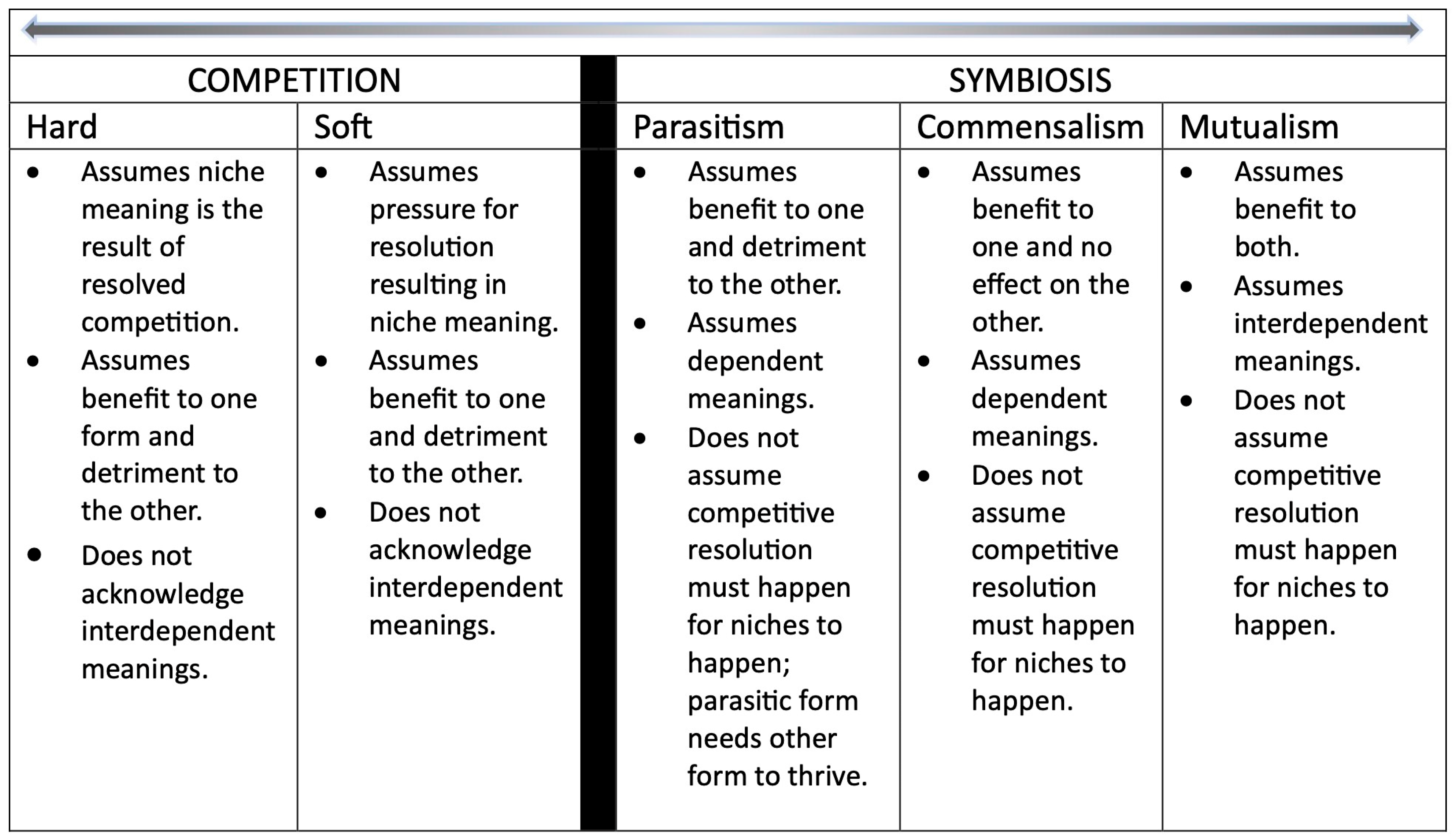

2.2. Competition and Symbiosis Models of Morphology: A Spectrum

In biology, strikingly similar forms or strategies may evolve in different locations or times, among organisms that occupy the same ecological niche… Such convergences arise not because of over-arching design or goals, but rather because similar interacting, local processes operate in many environments… in biology slight differences in form may arise because initial conditions are not the same or the ecological pressures differ.

2.3. Previous Studies of -eer

2.4. The Status of French in Medieval and Early Modern England

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Domains and Type Frequencies of -eer in the History of English

4.1.1. Phase 1 (1300–1699)

4.1.2. Phase 2 (1700–1999) and Data Type Frequencies

4.2. Compositionality and Analyzability of -eer

5. Competition, Symbiosis, and the Historical Development of -eer

5.1. The Ecological Model of Competition in Morphology

- (1)

- “Ishmael gives us a detail of whaling practice…the harpooneer throws both harpoons into the whale.” (Davies 2008–2024, BLOG; Moby-Dick Big Read, Day 63; patell.org)

- (2)

- “Avast there, avast there, Bildad, avast now spoiling our harpooneer…Pious harpooneers never make good voyagers”. (Davies 2008–2024, FIC: Review of Contemporary Fiction, vol. 29, Iss. 2, p. 15, 330 pgs; HERMAN MELVILLE or The Whale; Damion Searls)

5.2. The Ecological Model of Symbiotic Coexistence in Morphology

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The original cover is viewable here: https://www.bmimages.com/preview.asp?image=01613632138 (accessed on 8 March 2024). |

| 2 | At the same time, the -ity/-ness competition may be viewable as a type of symbiosis (perhaps commensalism). The spectrum proposed in Figure 1 is by no means static and is simply our effort to visualize the distinctions which may be relevant when analyzing forms in competition or symbiosis. |

| 3 | One other important note regarding orthography: the adjectival and nominal derivatives formed through the application of the comparative or nominalizing suffix -er to bases with word-final [i] (e.g., _[i] + -er) were not considered as part of the relevant data for this study. Though such derivatives are orthographically identical to nominal -eer derivatives that retain the <ier> spelling (e.g., financier), they are not similarly compositional compared to -eer derivatives (i.e., base + -eer). Thus, any such adjectival (e.g., heavier) or nominal derivatives (e.g., candier) were regarded as contaminates and not included in the analysis. |

| 4 | These derivatives are discussed regarding the diversification of the part of speech (adjective/verb/noun) of -eer derivatives over time but are not counted as part of the overall -eer data set because they do not represent constructions of the form “base + -eer.” |

| 5 | Another important note regarding token frequency: certain very-high-token-frequency constructions (e.g., engineer) and high-token-frequency proper names (e.g., Sawyer and Napier) skewed the overall frequency counts, in some instances misrepresenting the data due to the frequency of a single token. When this was the case, it is explicitly stated. |

| 6 | The miscellaneous domain was comprised of tokens that did not fit into the other six domains. The tokens in the miscellaneous domain are divided into five subcategories: “type of person” (e.g., grimacier), “mechanism” (e.g., eyeleteer), “objects” (e.g., etrier), “animals” (e.g., rockier), and “plants” (e.g., frambousier). |

| 7 | By “consistent” we mean that after the 16th century there are at least 8 adjectival or verbal derivatives counted in each century (i.e., 9 in the 17th century, 9 in the 18th century, 10 in the 19th century, and 8 in the 20th century). Also, this separation coincides with more orthographic consistency after the 17th century. |

| 8 | While chi-square tests show no statistical difference between the two highest percentages of -eer derivative usage—in the 17th and 18th centuries—there is a statistically significant difference between the peak of 4.8% in the 18th century and the 2.1% rate of the 16th century (p = 0.004) and the 2.7% rate of the 19th century (p = 0.020). |

| 9 | I.e., rippier, 1384; perrier, 1481; rapier, 1503; limoneer, 1524; besognier, 1584; volunteer, 1618; chicaneer, 1653; douzenier, 1682; ergoteer, 1687; Presbyteer, 1708; pompier, 1815; pikanier, 1816; macheer, 1847; menuisier, 1847; benitier, 1853; moskeneer, 1874; entremetier, 1874; entrier, 1955. |

| 10 | The term pion appears in EEBO, COHA, and COCA but without a consistent definition. In COCA, the frequency is zero because the term appears in contexts with a distinct meaning irrelevant to pioneer (since the 1950s, pion has been used with a very specific definition in particle physics). Frequencies from COHA are also counted as zero because they tend to constitute orthographic errors or variations with words such as champion or scorpion, as well as what seem to be alternate spellings of peon (‘an attendant’) and a few proper nouns. Only three occurrences in EEBO of the verb pion (meaning ‘to dig’) in 1590, 1648, and 1695 correspond to the early definition of pioneer (i.e., ‘a digger or excavator’). |

References

- Arndt-Lappe, Sabine. 2014. Analogy in suffix rivalry: The case of English -ity and -ness. English Language and Linguistics 18: 497–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, Mark. 2016. Competition and the lexicon. In Livelli di Analisi e Fenomeni di Interfaccia. Atti del XLVII Congresso Internazionale della Società di Linguistica Italiana. Edited by Annibale Elia, Claudio Iacobini and Miriam Voghera. Roma: Bulzoni Editore, pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, Mark. 2019. Competitors and alternants in linguistic morphology. In Competition in Inflection and Word-Formation. Edited by Franz Rainer, Francesco Gardani, Wolfgang U. Dressler and Hans Christian Luschützky. Cham: Springer, pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, Mark. 2023. Three ways of looking at morphological rivalry. Word Structure 16: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arppe, Antti, Gaëtanelle Gilquin, Dylan Glynn, Martin Hilpert, and Arne Zeschel. 2010. Cognitive corpus linguistics: Five points of debate on current theory and methodology. Corpora 5: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascoules, Sebastien, and Paul Smith. 2021. Mutualism between frogs (Chiasmocleis albopunctata, Microhylidae) and spiders (Eupalaestrus campestratus, Theraphosidae): A new example from Paraguay. Alytes 38: 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Laurie. 2001. Morphological Productivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Laurie. 2023. The birth and death of affixes and other morphological processes in English derivation. Languages 8: 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Laurie, Rochelle Lieber, and Ingo Plag. 2013. The Oxford Reference Guide to English Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, Geert. 2012. Construction morphology, a brief introduction. Morphology 22: 343–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, Geert. 2019. The role of schemas in construction morphology. Word Structure 12: 385–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, Geert, and Jenny Audring. 2018. Partial motivation, multiple motivation: The role of output schemas in morphology. Studies in Morphology 4: 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Burnley, David. 1992. Lexis and semantics. In The Cambridge History of the English Language. Edited by Norman Blake. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 409–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A Study of the Relation Between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2006. Frequency of Use and the Organization of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage, and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, and Clay Beckner. 2015. Emergence at the cross-linguistic level: Attractor dynamics in language change. In The Handbook of Language Emergence. Edited by Brian MacWhinney and William O’Grady. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, Claire, and Christiane Dalton-Puffer. 2002. Diachronic word-formation and studying changes in productivity over time: Theoretical and methodological considerations. In A Changing World of Words. Edited by Javier E. Díaz Vera. Boston: Brill, pp. 410–37. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2001. Radical Construction Grammar: Syntactic Theory in Typological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton-Puffer, Christiane. 1996. The French Influence on Middle English Morphology: A Corpus-Based Study on Derivation. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). 2008–2024. Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Davies, Mark. 2010. The Corpus of Historical American English (COHA). Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Davies, Mark. 2017. Early English Books Online Corpus (EEBO). Available online: https://www.english-corpora.org/eebo/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Divjak, Dagmar. 2006. Ways of intending: Delineating and structuring near-synonyms. In Corpora in Cognitive Linguistics: Corpus-Based Approaches to Syntax and Lexis. Edited by Stefan Gries and Anatol Stefanowitsch. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dundee, Harold, Cara Shillington, and Colin M. Yeary. 2012. Interactions between tarantulas (Aphonopelma hentzi) and narrow-mouthed toads (Gastrophyrne olivacea): Support for a symbiotic relationship. Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 32: 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Alcaina, Cristina, and Jan Čermák. 2018. Derivational paradigms and competition in English: A diachronic study on competing causative verbs and their derivatives. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 15: 69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Domínguez, Jesús. 2017. Methodological and procedural issues in the quantification of morphological competition. In Competing Patterns in English Affixation. Edited by Juan Santana Lario and Salvador Valera. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 67–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gause, Gregory. 1934. The Struggle for Existence. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Company. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts, Dirk, Dirk Speelman, Kris Heylen, Mariana Montes, Stefano De Pascale, Karlien Franco, and Michael Lang. 2023. Lexical Variation and Change: A Distributional Semantic Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele. 1995. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Adele. 2019. Explain Me This: Creativity, Competition, and the Partial Productivity of Constructions. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, Stefan. 2001. A corpus-linguistic analysis of English-ic vs-ical adjectives. Icame Journal 25: 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, Patrick. 2013. Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer. 2003. Causes and Consequences of Word Structure. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer, and Harald Baayen. 2002. Parsing and productivity. In Yearbook of Morphology 2001. Edited by Geert Booij and Jaap Van Marle. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 203–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert, Martin. 2013. Constructional Change in English: Developments in Allomorphy, Word Formation, and Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hippisley, Andrew, and Gregory Stump. 2016. The Cambridge Handbook of Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Thomas. 2022. Construction Grammar: The Structure of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hüning, Matthias, and Geert Booij. 2014. From compounding to derivation the emergence of derivational affixes through “constructionalization”. Folia Linguistica 48: 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, Richard, and Rossella Varvara. 2023. Affix rivalry: Theoretical and methodological challenges. Word Structure 16: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunisto, Mark. 2007. Variation and Change in the Lexicon: A Corpus-based Analysis of Adjectives in English Ending in -ic and -ical. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi B. V. [Google Scholar]

- Kibbee, Douglas A. 1991. For to Speke Frenche Trewely: The French Language in England, 1000–1600: Its Status, Description, and Instruction. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub., Co. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar: Theoretical Prerequisites. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Benoît, and Cameron Morin. 2023. No equivalence: A new principle of no synonymy. Constructions 15: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Rochelle. 2016. English Nouns: The Ecology of Nominalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Mark, and Mark Aronoff. 2013. Natural selection in self-organizing morphological systems. In Morphology in Toulouse: Selected Proceedings of Décembrettes 7. Edited by Fabio Montermini, Gilles Boyé and Jesse Tseng. Munich: Lincom Europe, pp. 133–53. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, Hans. 1960. The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word Formation. Weisbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Mattiello, Elisa. 2018. Paradigmatic morphology splinters, combining forms, and secreted affixes. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 15: 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, Andrés, Juli Peretó, Rosario Gil, and Amparo Latorre. 2008. Learning how to live together: Genomic insights into prokaryote-animal symbioses. Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 218–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, Akiko. 2023. Affixal rivalry and its purely semantic resolution among English derived adjectives. Journal of Linguistics 59: 499–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Karen L., and Robin M. Leichenko. 2003. Winners and losers in the context of global change. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Chris C. 2008. Borrowed derivational morphology in Late Middle English: A study of the records of the London Grocers and Goldsmiths. In Studies in the History of the English Language IV: Empirical and Analytical Advances in the Study of English Language Change. Edited by Susan M. Fitzmaurice and Donka Minkova. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 231–64. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Chris C. 2009. Borrowings, Derivational Morphology, and Perceived Productivity in English, 1300–1600. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Chris C. 2015. Measuring productivity diachronically: Nominal suffixes in English letters, 1400–1600. English Language and Linguistics 19: 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plag, Ingo. 1999. Morphological Productivity. Structural Constraints in English Derivation. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Puente, Paula, Tanja Säily, and Jukka Suomela. 2022. New methods for analysing diachronic suffix competition across registers: How -ity gained ground on -ness in Early Modern English. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 27: 506–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Isabel. 2010. Explore the influence of French on English. Leading Undergraduate Work in English Studies 3: 255–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, William. 1998. Arrivals and departures: The adoption of French terminology into Middle English. English Studies 79: 144–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, William. 2001. English and French in England after 1362. English Studies 82: 539–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifart, Frank. 2015. Direct and indirect affix borrowing. Language 91: 511–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Chris A. 2020. A case study of -some and -able derivatives in the OED3: Examining the diachronic output and productivity of two competing adjectival suffixes. Lexis 16: 279–387. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Chris A. How is stickage different from sticking? A study of the semantic behaviour of V-age and V-ing nominalisations (on monomorphemic bases). In Nouns and the Morphosyntax/Semantics Interface. Edited by Laure Gardelle, Elise Mignot and Julie Neveux. New York: Springer International Publishing, Forthcoming.

- Štekauer, Pavol. 2017. Competition in natural languages. In Competing Patterns in English Affixation. Edited by Juan Santana Lario and Salvador Valera. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tichý, Ondřej. 2018. Lexical obsolescence and loss in English: 1700–2000. In Applications of Pattern-Driven Methods in Corpus Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, Michael. 2005. Constructing a Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth, and Graeme Trousdale. 2013. Constructionalization and Constructional Changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Terry. 2017. he saith yt he think es yt: Linguistic factors influencing third person singular present tense verb inflection in Early Modern English depositions. Studia Neophilologica 89: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trade | 11 | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| military | X | 1 | 17 | 15 |

| political | X | X | X | 6 |

| religious | X | 1 | X | 8 |

| art | X | X | X | 4 |

| miscellaneous | X | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| food | 1 | X | X | X |

| Domain | Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| trade | 8 | 15 | 17 |

| military | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| political | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| religious | 1 | 1 | X |

| art | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| miscellaneous | 6 | 10 | 3 |

| food | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 1100–1199 | 1200–1299 | 1300–1399 | 1400–1499 | 1500–1599 | 1600–1699 | 1700–1799 | 1800–1899 | 1900–1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.5% | 3.1% | 3% | 1.1% | 2.1% | 3.9% | 4.8% | 2.7% | 3.6% |

| Orthography | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <-eer> | 1 | 0 | 8 | 37 | 22 | 33 | 28 |

| <-ier> | 11 | 7 | 21 | 15 | 5 | 19 | 8 |

| 1100–1199 | 1200–1299 | 1300–1399 | 1400–1499 | 1500–1599 | 1600–1699 | 1700–1799 | 1800–1899 | 1900–1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 66.6% | 91.7% | 71.4% | 89.7% | 92.3% | 96.3% | 86.5% | 97.2% |

| 14th Century | 15th Century | 16th Century | 17th Century | 18th Century | 19th Century | 20th Century |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pannier (1300) | hosier (1403) | pioneer (1517) | ballistier (1609) | auctioneer (1708) | cabineteer (1810) | profiteer (1912) |

| furrier (1330) | sievier (1440) | staffier (1524) | petardier (1632) | consortier (1728) | bludgeoneer (1852) | imagineer (1942) |

| clothier (1362) | ropier (1440) | musketeer (1590) | covenanteer (1660) | phaetoneer (1795) | animalier (1884) | motelier (1959) |

| Derivative (Century First Attested) | EEBO | COHA | COCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| pannier (14th) | 11.39 | 13.05 | 8.19 |

| furrier (14th) | 5.56 | 27.00 | 14.08 |

| clothier (14th) | 52.05 | 24.42 | 15.57 |

| hosier (15th) | 17.08 | 3.58 | 2.50 |

| sievier (15th) | 0.13 | X | X |

| ropier (15th) | 0.26 | X | 0.10 |

| pioneer (16th) | 4.37 | 866.05 | 744.20 |

| staffier (16th) | 0.13 | X | X |

| musketeer (16th) | 1.32 | 13.68 | 20.67 |

| ballistier (17th) | X | X | X |

| petardier (17th) | 1.99 | X | X |

| covenanteer (17th) | 1.85 | X | X |

| auctioneer (18th) | 0.79 | 178.72 | 74.58 |

| consortier (18th) | X | X | X |

| phaetoneer (18th) | X | X | X |

| cabineteer (19th) | X | 0.21 | X |

| bludgeoner (19th) | X | X | X |

| animalier (19th) | X | X | 0.30 |

| profiteer (20th) | X | 18.95 | 11.78 |

| imagineer (20th) | X | 0.21 | 0.90 |

| motelier (20th) | X | X | 0.10 |

| Base (Century First Attested) | EEBO | COHA | COCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| pan (pre-11th) | 1678.24 | 2179.64 | 2686.07 |

| fur (14th) | 210.97 | 2368.68 | 923.11 |

| cloth (pre-11th) | 2752.30 | 3059.58 | 1323.07 |

| hose (13th) | 450.81 | 730.06 | 554.21 |

| sieve (pre-11th) | 96.15 | 133.04 | 97.54 |

| rope (pre-11th) | 612.39 | 2655.19 | 1422.21 |

| pion (17th) | 0.40 | X | X |

| staff (pre-11th) | 759.66 | 6363.57 | 10,953.65 |

| musket (16th) | 266.99 | 403.34 | 83.57 |

| ballista (pre-11th) | 1.59 | 2.32 | 3.59 |

| petard (16th) | 29.14 | 22.52 | 14.98 |

| covenant (13th) | 15,115.12 | 501.86 | 589.85 |

| auction (16th) | 31.52 | 601.01 | 1022.55 |

| consort (16th) | 551.47 | 181.46 | 79.57 |

| phaeton (16th) | 116.94 | 72.00 | 10.18 |

| cabinet (16th) | 485.51 | 3249.05 | 1781.03 |

| bludgeon (18th) | X | 53.89 | 32.95 |

| animal (14th) | 2268.64 | 6835.12 | 5828.21 |

| profit (14th) | 6501.58 | 3492.40 | 2911.41 |

| imagine (14th) | 4405.64 | 6315.37 | 8501.30 |

| motel (20th) | X | 609.85 | 832.86 |

| Derivative (Century First Attested) | EEBO | COHA | COCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| pannier (14th) | 147.35 | 167 | 328.1 |

| furrier (14th) | 37.93 | 84.6 | 65.57 |

| clothier (14th) | 52.88 | 125.29 | 84.95 |

| hosier (15th) | 26.39 | 204 | 222.04 |

| sievier (15th) | 726 | MAX | MAX |

| ropier (15th) | 2312 | MAX | 14,245 |

| pioneer (16th) | 0.09 | 0 | 0 |

| staffier (16th) | 5736 | MAX | MAX |

| musketeer (16th) | 201.6 | 29.48 | 4.04 |

| ballistier (17th) | MAX | MAX | MAX |

| petardier (17th) | 14.67 | MAX | MAX |

| covenanteer (17th) | 8152.21 | MAX | MAX |

| auctioneer (18th) | 39.67 | 3.36 | 13.71 |

| consortier (18th) | MAX | MAX | MAX |

| phaetoneer (18th) | MAX | MAX | MAX |

| cabineteer (19th) | MAX | 15,434 | MAX |

| bludgeoner (19th) | ? | MAX | MAX |

| animalier (19th) | MAX | MAX | 19,458.67 |

| profiteer (20th) | MAX | 184.33 | 247.13 |

| imagineer (20th) | MAX | 30,000 | 9461.11 |

| motelier (20th) | ? | MAX | 8342 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dukic, Z.; Palmer, C.C. The History of -eer in English: Suffix Competition or Symbiosis? Languages 2024, 9, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9030102

Dukic Z, Palmer CC. The History of -eer in English: Suffix Competition or Symbiosis? Languages. 2024; 9(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleDukic, Zachary, and Chris C. Palmer. 2024. "The History of -eer in English: Suffix Competition or Symbiosis?" Languages 9, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9030102

APA StyleDukic, Z., & Palmer, C. C. (2024). The History of -eer in English: Suffix Competition or Symbiosis? Languages, 9(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9030102