Features of Grammatical Writing Competence among Early Writers in a Norwegian School Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

So, whereas rule-based grammar divides language into two absolute categories—correct and incorrect—rhetorical grammar treats grammatical choice as, well, precisely that: a choice from among possibilities. These possibilities are judged as more or less effective, depending upon factors such as audience, purpose and context.

2. Writing Competence

3. Previous Studies about Grammatical Writing Competence

Although the average child in the fourth grade produces virtually all the grammatical structures ever described in a course in school grammar, he does not produce as many at the same time—as many inside each other, or on top of each other—as older students do.

- (1)

- We often run around in the schoolyard.

- (2)

- In the schoolyard, we often run around.

- (3)

- Often, we run around in the schoolyard.

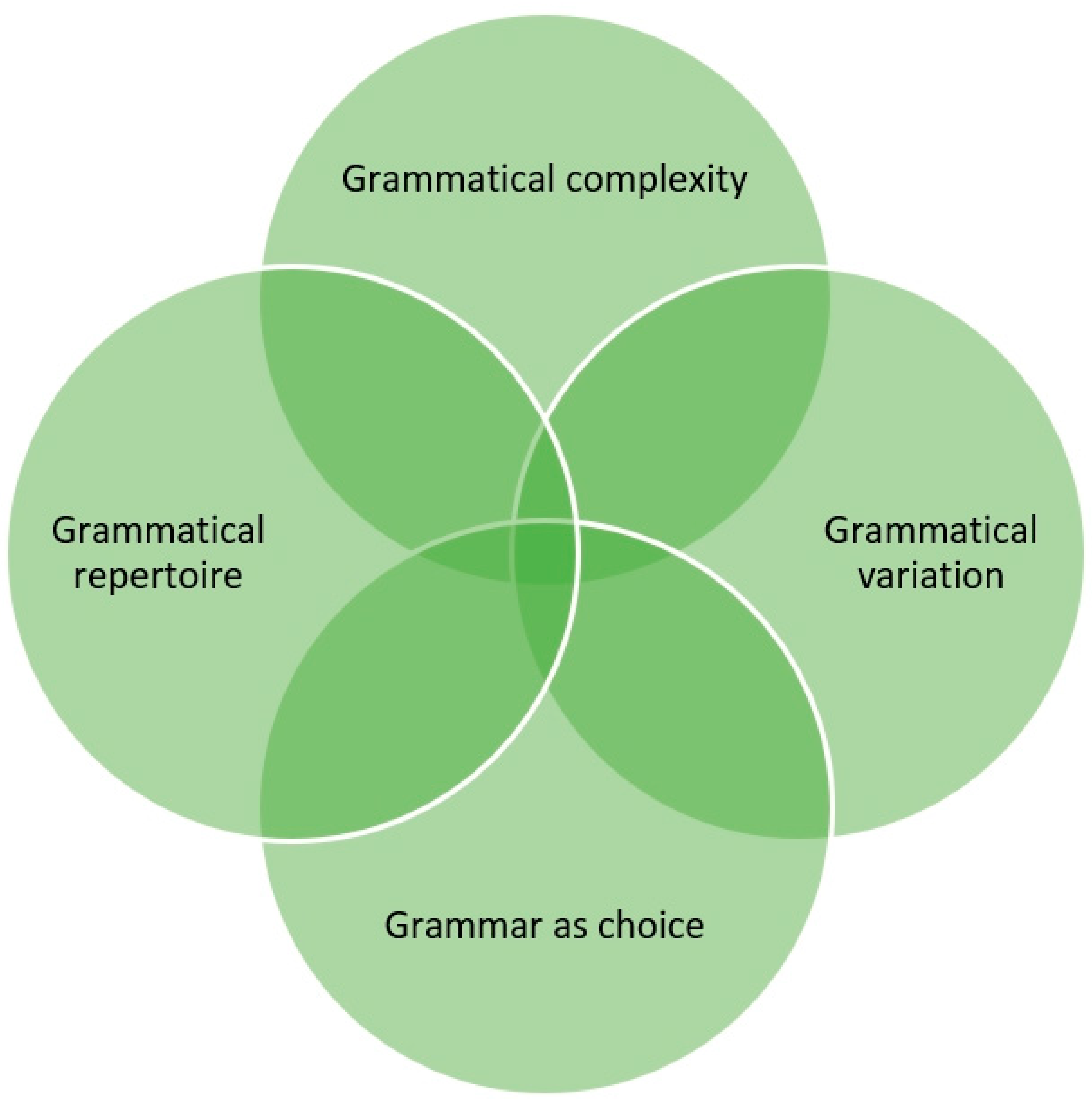

4. Untangling Subparts of Grammatical Writing Competence

Children appear to have access to the core grammatical structures of English by the time they start school. Instead, a key change concerns their “ability to manage an increasing degree of structural complexity”.

(…) complexity refers to a property or quality of a phenomenon or entity in terms of (1) the number and the nature of the discrete components that the entity consists of, and (2) the number and the nature of the relationships between the constituent components.

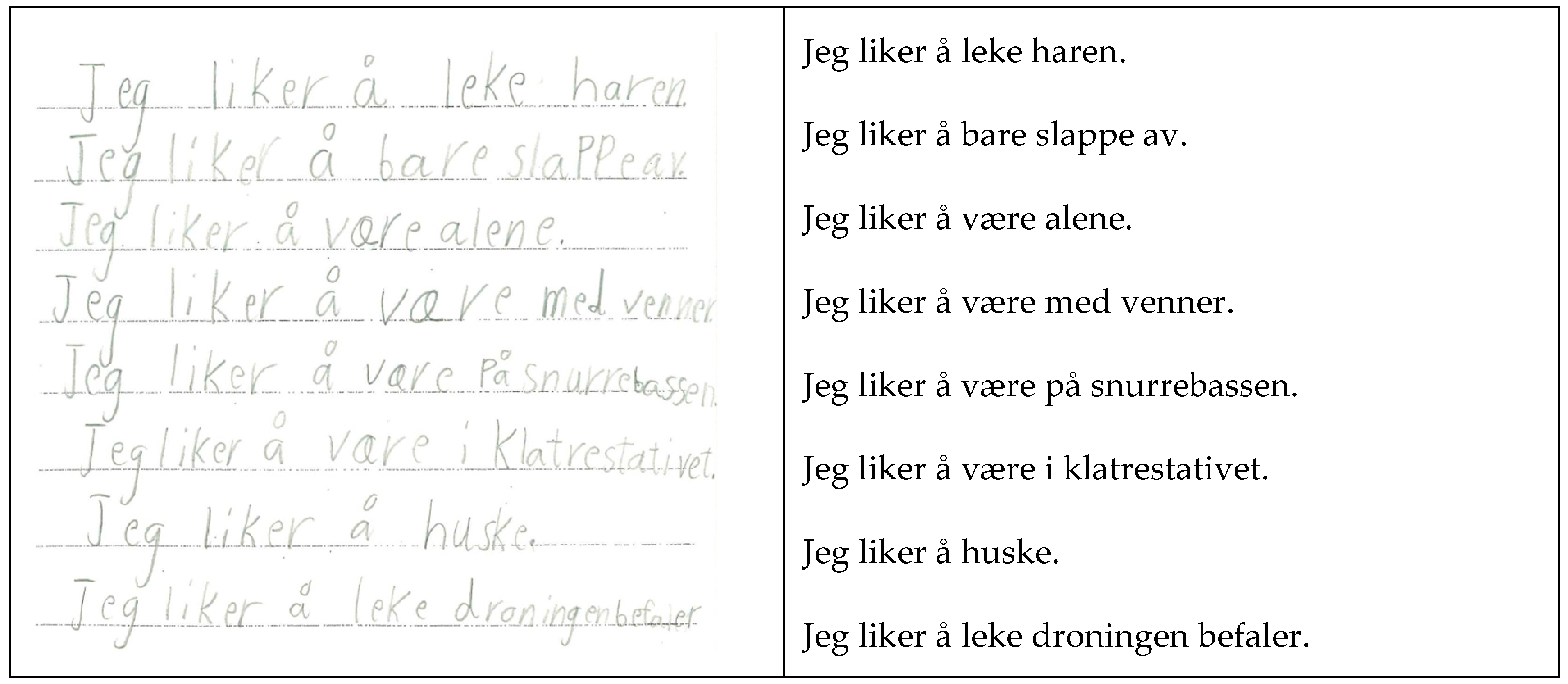

I like to play tag.

I like to just relax.

I like to be alone.

I like to be with friends.

I like to be on the carousel.

I like to be on the climbing frame.

I like to play on the swing.

I like to play Simon says.

Text 253035, MP2 Outdoor activities (see original Norwegian text in Appendix A)

I like to play football, dodgeball, kick the can and

to Minecraft. Football is fun

because it is exciting and because it is sport.

There are many of us on the field. Dodgeball

is fun because you can throw a ball at

someone

and because you are moving.

We are many on the

field. Kick the can is fun

because you have to

sneak behind the one who is

it. Minecraft is fun

because you play the game.

Text 756057, MP0 Outdoor Activities4

The point of grammar study is to enable pupils to make choices from among a range of linguistic resources and to be aware of the effects of different choices on the rhetorical power of their writing.

5. Methods for Data Collection and Analysis

5.1. The Data Set

Outdoor Activities: Write a letter to the researchers about what you like to do during the outdoor school breaks;

Magical Hat: Imagine that you find a magical hat. When you put it on, you can change into anything you want. Tell the reader about what you transform into and what happens on that day.

5.2. Method of Analysis

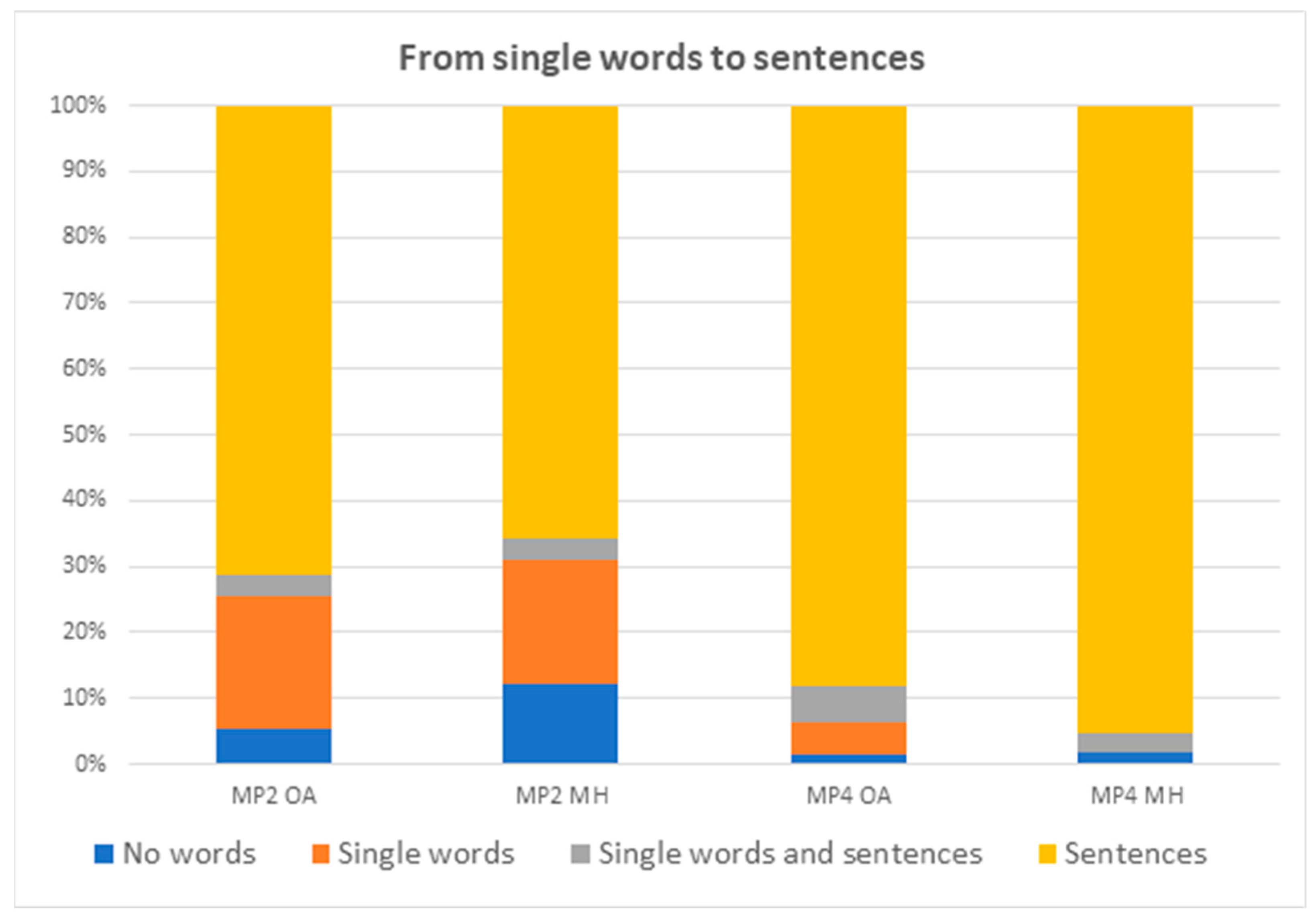

6. Results

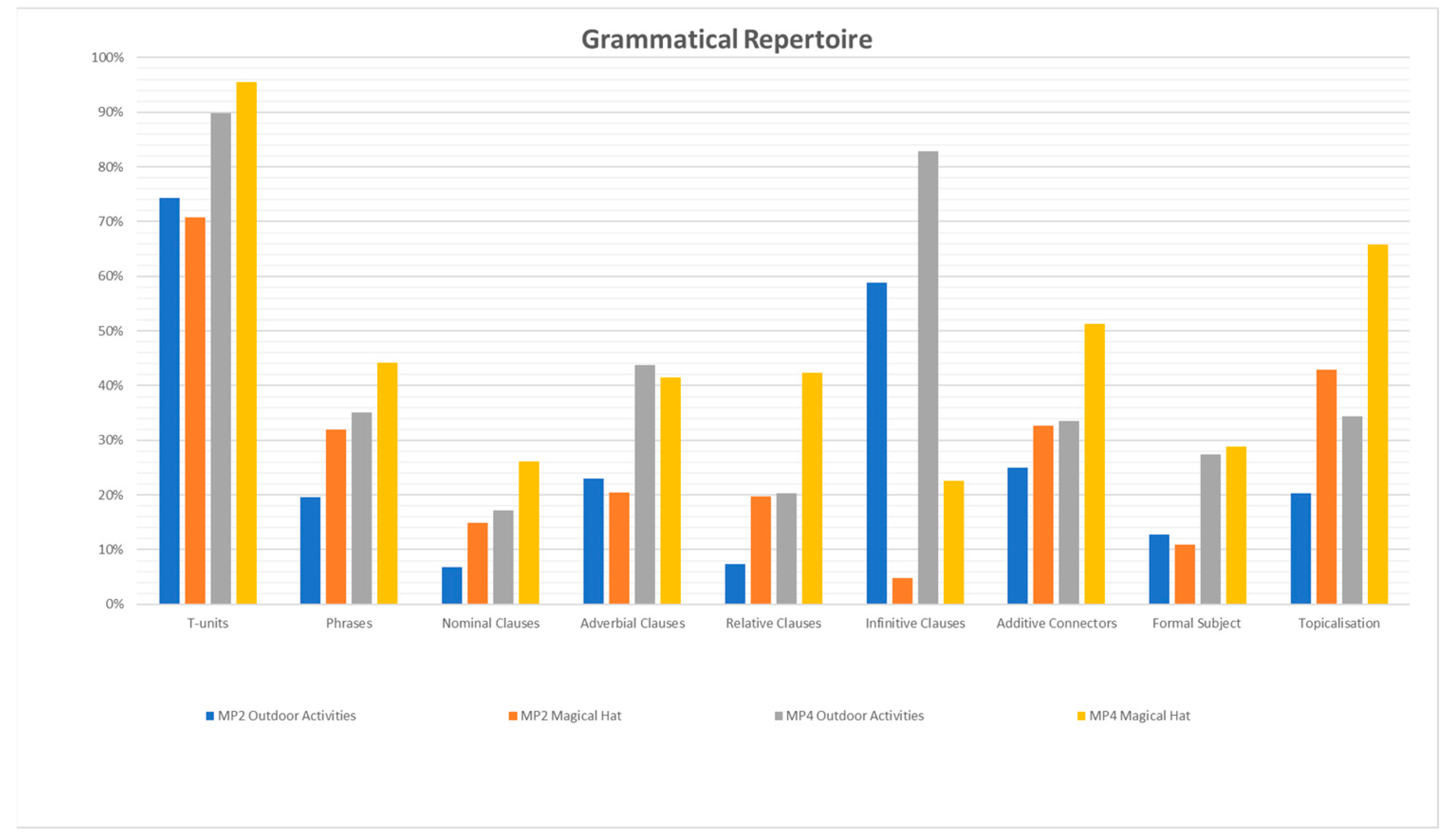

6.1. Grammatical Repertoire and Complexity

- (4)

- If I found a magical hat, I would…

- (5)

- I found a magical hat. When I put it on I knew that the world would never be the same again. When I walked in that door there were lots of my family there.

- (6)

- When we are on the climbing frame, there is also someone who is playing tag.

6.2. Grammatical Variation and Choice

I like to play tag.

I like to just relax.

I like to be alone.

I like to be with friends.

I like to be on the carousel.

I like to be on the climbing frame.

I like to play on the swing.

I like to play Simon says.

Text 253035, MP2 Outdoor Activities

To the researchers,

In winter I like to build a snowman.

I also like to go sledging. I like to slide.

When a lot of snow has come dad

used to shovel snow and put it in a pile.

Then I use to jump from the shed and right

into the grove. I think that’s fun.

In spring I like to cycle and to be outside.

I like to do handstands and skip rope.

The sun gets higher in the sky in summer.

Then we can go to the beach. There we

can have a swim in cold water. I like to swim.

When I ask if someone wants to play kick the can

many of them want to. I like to be together.

In autumn I like to walk around for Halloween

I like to make the house look scary with spiders and pumpkins.

I like to dress up on Halloween.

In autumn leaves fall from the trees.

I usually gather it and throw it in the air.

Text450019, MP4 Magical Hat

Magical hat

If I found a magical hat then I would

be a unicorn. As a unicorn I would

ride a sledge on the rainbow and fly very

high in the sky and dress up with

ribbons and play hide and seek with

other unicorns. I would also find a

treasure that contains many jewels. I would

have pink fur and light blue horns.

Text 256009, MP4 Magical Hat

- (7)

- I usually play on the playground. There I normally climb. I sometimes play quietly, but that doesn’t happen too often.

- (8)

- If I had found a magical hat then I would have wished I would wish that I became a mermaid.

- (9)

- If I found a magical hat I would have become a rabbit and driven a car.

Dog. I went for a walk with my owner

and ate food. Then I played

with chewing toys. Then I wanted to sleep.

Then I woke up.

Text262032, MP2 Magical Hat

Magical Hat

I wish that the swimming pool would open

I wish that the aeroplane would open and that I would get candy every day

And that I didn’t go to school

And that the circus would open

And that coronavirus would disappear forever

Text 253023, MP2 Magical Hat

Outdoor Activities

Football is fun because it is exciting and because it is sport.

Dodgeball is fun because one can throw a ball at people and because you are moving around.

Text 254056, MP2 Outdoor Activities

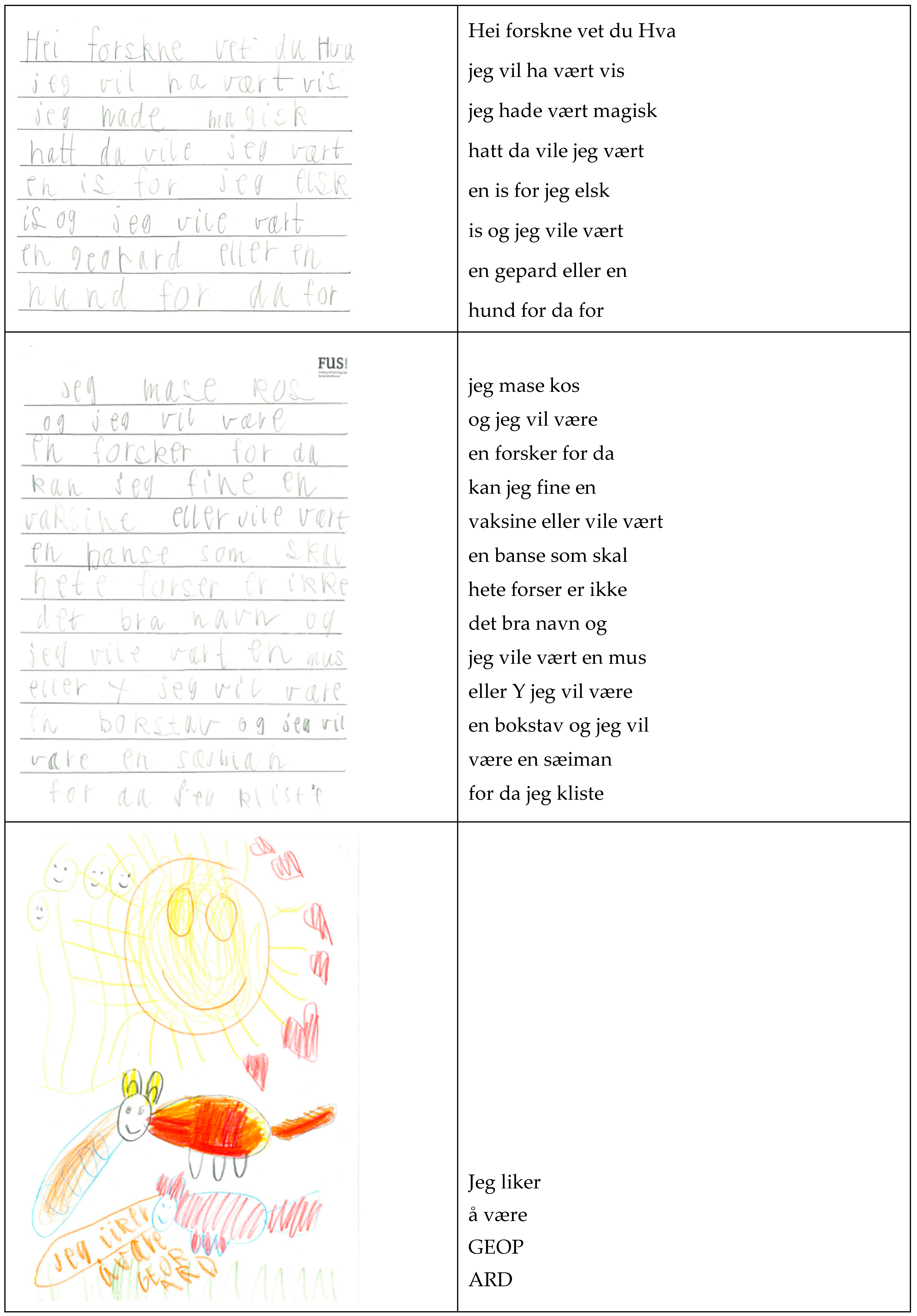

Hi researchers,

Do you know what I would have been if I had a magical hat then I would have been an ice cream because I love ice cream and I would have been a cheetah or a dog because then I get a lot of hugs and I want to be a researcher because then I can find a vaccine or would have been a teddy bear named researcher isn’t that a great name and I would have been a mouse or a Y I want to be a letter and I want to be a gummy bear because then I stick.

I like to be a cheetah

Text 260047, MP2 Magical Hat (see original Norwegian text in Appendix A)

7. Discussion

To the researchers,

When I find the hat then I will get a kitten

and I can fly

and I can swim in candy

and I fly over every city

and everything is fun.

And I will be really good at gymnastics

and that I get superpower

and I can walk on water.

Text 255001, MP4 Magical Hat

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | This is also generally highly valued in the evaluation of the students’ texts (see also Hertzberg 2005). |

| 2 | The distinctions are not relevant to our study, as we are not measuring the effects of teaching. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | MP0 (measure point zero) refers to a sample of texts that were collected prior to the intervention in the project. It served as a pilot sample for our study. More about the intervention in Section 4. |

| 5 | In some studies, fluency also refers to the number of words written in a given amount of time (e.g., Skar et al. 2022). This is, however, not the definition we are aiming for. |

| 6 | More specifically, the teachers in FUS reported that 83.2% had Norwegian as their L1. 10.7% had learned both Norwegian and another language from birth, whereas 5.9% reported another language as their L1 (Skar et al. 2023). |

| 7 | The eight rating scales created were Audience Awareness (S1), Vocabulary (S3), Organisation of Content (S4), Language Use (S5), Punctuation (S6), Spelling (S7), Handwriting (S8), and Relevance (S9). |

| 8 | MP0 served as a pilot for our study, as aforementioned. |

| 9 | A similar solution is chosen by Myhill et al. (2012). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | It is a theoretical question whether an infinitive construction should be included as a subordinate clause due to its structure being parallel to subordinate clauses or whether it should be considered a nominal constituent, as it has no tense. For our purposes, this has no importance for the analysis. |

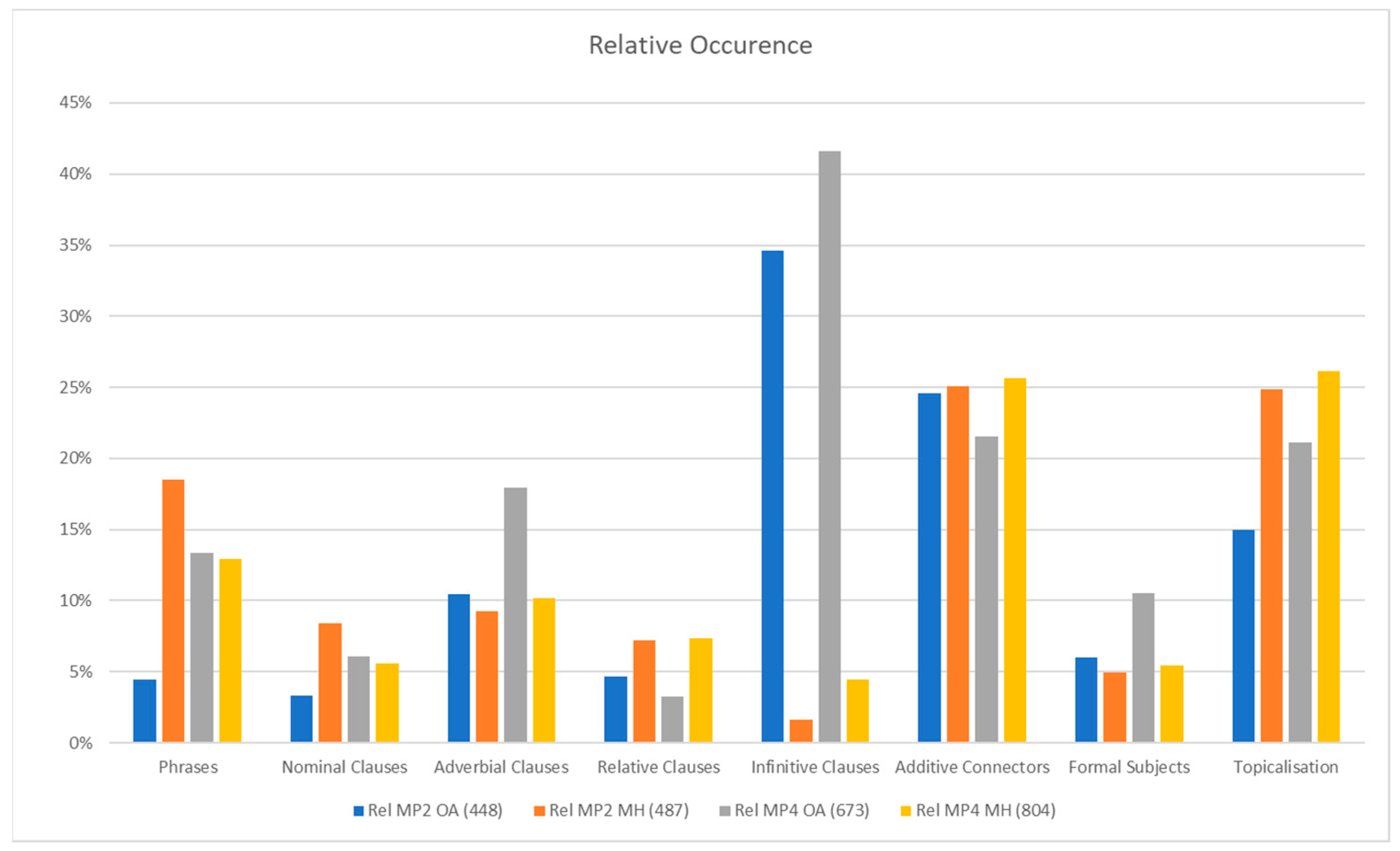

| 12 | When we adjust for text length (see Figure 4), the result is slightly different, but the tendencies remain similar. |

| 13 | This also applies to other results in this section. |

| 14 | In this study, we have counted T-units, not single words, which means that the measures of text length are not precise, but the overall impression is quite obvious at this point. The numbers of T-units are 448 (MP2 Outdoor Activities), 487 (MP2 Magical Hat), 673 (MP4 Outdoor Activities), and 804 (MP4 Magical Hat). |

| 15 | The main reason that a substantial number of features do not occur in the “below average” group is that the majority of texts in this group were either non-verbal (only a drawing) or in the form of single words, a list or maybe one full sentence. |

References

- Applebee, Arthur. 2000. Alternative Models of Writing Development. In Perspectives on Writing: Research, Theory and Practice. Edited by Roselmina Indrisano and James R. Squire. Newark: IRA. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 1992. A Second Look at T-Unit Analysis: Reconsidering the Sentence. TESOL Quarterly 26: 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterrechea, Maria, and Regina Weinert. 2017. Examining the concept of Subordination in Spoken L1 and L2 English: The Case of If-clauses. TESOL Quarterly 51: 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berninger, Virginia W. 1999. Coordinating Transcription and Text Generation in Working Memory during Composing: Automatic and Constructive Processes. Learning Disability Quarterly 22: 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, Douglas, Bethany Gray, and Kornwipa Poonpon. 2011. Should we use characteristics of conversation to measure grammatical complexity in L2 writing development? TESOL Quarterly 45: 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormuth, John R. 1969. Development of Readability Analyses. Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bulté, Bram, and Alex Housen. 2012. Defining and operationalising L2 complexity. In Dimensions of L2 Performance and Proficiency. Complexity, Accuracy and Fluency in SLA. Edited by Alex Housen, Folkert Kuiken and Ineke Vedder. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Ronald, and Michael McCarthy. 2006. Cambridge Grammar of English: A Comprehensive Guide: Spoken and Written English Grammar and Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chall, Jeanne, and Edgar Dale. 1995. Readability Revisited: The New Dale-Chall Readability Formula. Brookline: Brookline Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structures. New York: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1980. Rules and Representations. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use. New York: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Crain, Stephen, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 1999. An Introduction to Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed. New York: SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, Scott A. 2020. Linguistic features in writing quality and development: An overview. Journal of Writing Research 11: 415–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culham, Ruth. 2003. 6 + 1 Traits of Writing: The Complete Guide Grades 3 and up. New York: Scholastic Professional Books. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniewska, Pam. 1992. Learning about Writing: The Early Years. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, Philip, Mark Brenchley, and Lee McCallum. 2021. Understanding Development and Proficiency in Writing. Quantitive Corpus Linguistic Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, Lars S. 1997. Å skrive seg stor: Utvikling av koherens og sosial identitet i tidlig skriving. In Skriveteorier og skolepraksis. Edited by Lars S. Evensen and Torlaug L. Hoel. Oslo: LNU og Cappelen Akademisk Forlag, pp. 155–78. [Google Scholar]

- Faarlund, Jan Terje, Svein Lie, and Kjell Ivar Vannebo. 1997. Norsk Referansegrammatikk. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Giere, Ronald N. 1997. Understanding Scientific Reasoning, 4th ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael A. K. 1975. Learning How to Mean: Explorations in the Development of Language. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael A. K., and Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal, Sara, Klara Korsgaard, and Monique Vitger. 2011. Oppdagende Skriving—En vei inn i Lesingen. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Harpin, William S. 1976. The Second ‘R’: Writing Development in the Junior School, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselgård, Hilde. 2004. Thematic choice in English and Norwegian. Functions of Language 11: 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselgård, Hilde. 2005. Theme in Norwegian. In Semiotics from the North: Nordic Approaches to Systemic Functional Linguistics. Edited by Kjell Lars Berge and Eva Maagerø. Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg, Frøydis. 2001. Tusenbenets vakre dans: Forholdet mellom formkunnskap og sjangerbeherskelse. Rhetorica Scandinavica 18: 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg, Frøydis. 2005. Setningsemner—Risikotrekket som forsvant. Eksempler fra KAL-materialet. In Mot rikare mål å trå. Festskrift til Tove Bull. Edited by Gulbrand Alhaug, Endre Mørck and Aud-Kirsti Pedersen. Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 314–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hognestad, Jan. 2021. Syntaks. In Norskboka 1–7, 2nd ed. Edited by Mari Nygård and Christian Bjerke. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Høigård, Anne. 2019. Barns Språkutvikling: Muntlig og Skriftlig, 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Hundal, Anne Kathrine. 2017. Skriveutvikling på mellomtrinnet: En undersøkelse av sammenhengsmekanismer i elevtekster og hvilke didaktiske forhold som bidrar til utvikling av sammenheng i tekst. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Kellogg W. 1965. Grammatical Structures Written and Three Grade Levels. Research Report No. 3. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED113735 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Iversen, Harald Morten, and Hildegunn Otnes. 2013. Kohesjon og forfelt—To aspekt i skriftlige elevtekster. In Literacy i Læringskontekster. Edited by Dagrun Skjelbred and Aslaug Veum. Oslo: Cappelen Damm akademisk, pp. 281–97. [Google Scholar]

- Juel, Connie L. 1988. Learning to Read and Write: A Longitudinal Study of 54 Children from First through Fourth Grades. Journal of Educational Psychology 80: 437–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, Günther. 1994. Learning to Write. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kristoffersen, Cherise. 2023. A Shared Terminology for Writing in the Primary Grades for Writers and Their Teachers: With a Focus on Word Choice and Sentence Fluency. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Lefstein, Adam. 2009. Rhetorical grammar and the grammar of schooling: Teaching “powerful verbs” in the English National Literacy Strategy. Linguistics and Education 20: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loban, Walter. 1976. Language Development: Kindergarten through Grade Twelve. Research Report 18. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentzen, Rutt T. 2009. Den tidlige skriveutviklinga. In Norskdidaktikk—Ei grunnbok. Edited by Jon Smidt. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, pp. 112–34. [Google Scholar]

- Maagerø, Eva, Henriette Siljan, and Aslaug Veum. 2021. Going from oral to written discourse: Norwegian students’ grammatical challenges when writing persuasive texts. Linguistics and Education 66: 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, A. J., Gill L. Elliott, and Nat K. Johnson. 2005. Variations in Aspects of Writing in 16+ English Examinations between 1980 and 2004: Vocabulary, Spelling, Punctuation, Sentence Structure. Research Matters: Special Issue 1: 1–118. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen, Deborah. 2000. Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist 35: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Danielle, Scott A. Crossley, and Philip M. McCarthy. 2010. Linguistic Features of Writing Quality. Written Communication 27: 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Research. 2020. Curriculum in Norwegian (NOR-0106). Available online: https://www.udir.no/lk20/nor01-06 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Myhill, Debra. 2008. Towards a linguistic model of sentence development in writing. Language and Education 22: 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhill, Debra. 2009. From talking to writing: Linguistic development in writing. British Journal of Educational Psychology Monograph Series 11: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Myhill, Debra, Susan M. Jones, Helen Lines, and Annabel Watson. 2012. Re-thinking grammar: The impact of embedded grammar teaching on students’ writing and students’ metalinguistic understanding. Research Papers in Education 27: 139–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, John M., and Lourdes Ortega. 2009. Towards an Organic Approach to Investigating CAF in Instructed SLA: The Case of Complexity. Applied Linguistics 30: 555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygård, Mari. 2023. Setningsemner i elevtekster. In Elevtekstanalysar. Nye Inngangar. Edited by Ola Harstad and Leiv Inge Aa. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2003. Grammatical Complexity Measures and their Relationship to L2 Proficiency: A Research Synthesis of College-level L2 Writing. Applied Linguistics 24: 492–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1994. Semiotikk og Pragmatisme. København: Gyldendal. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, Katherine. 1984. Children’s Writing and Reading: Analysing Classroom Language. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, Katherine. 1986. Grammatical differentiation between speech and writing in children aged 8–12. In The Writing of Writing. Edited by Andrew Wilkinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, Katherine. 1987. Understanding Language. Hunnington: National Association of Advisers in English. [Google Scholar]

- Puranik, Cynthia S., and Christopher J. Lonigan. 2014. Emergent Writing in Preschoolers: Preliminary Evidence for a Theoretical Framework. Reading Research Quarterly 49: 453–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardamalia, Marlene, and Carl Bereiter. 1987. Knowledge telling and knowledge transforming in written composition. In Advances in Applied Pshycolinguistics. Edited by Sheldon Rosenberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 142–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, Carson T. 1996. The Empirical Base of Linguistics. Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, and Debra Myhill. 2021. Exploring of Multiple Perspectives on Early Writing Development. In Skriveutvikling og skrivevansker. Edited by Kari-Anne B. Næss and Hilde Hofslundsengen. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, Arne Johannes Aasen, and Lennart Jølle. 2020a. Functional Writing in the Primary Years: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Writing Intervention Study. Nordic Journal of Literacy Research 6: 201–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, Lennart Jølle, and Arne Johannes Aasen. 2020b. Establishing Rating Scales to Assess Writing Proficiency Development in Young Learners. Acta Didactica Norden 14: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, Pui-Wa Lei, Steve Graham, Arne Johannes Aasen, Marita Byberg Johansen, and Anne Holten Kvistad. 2022. Handwriting fluency and the quality of primary grade students’ writing. Reading & Writing 35: 509–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, Ragnar Thygesen, and Lars Sigfred Evensen. 2017. Assessment for Learning and Standards: A Norwegian Strategy and Its Challenges. In Standard Setting in Education. Methodology of Educational Measurement and Assessment. Edited by Sigrid Blömeke and Jan-Eric Gustafsson. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, Gustaf Bernhard Uno, Steve Graham, Alan Huebner, Anne Holten Kvistad, Marita Byberg Johansen, and Arne Johannes Aasen. 2023. A longitudinal intervention study of the effects of increasing amount of meaningful writing across grades 1 and 2. Reading and Writing 8: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Åse Kari H., Sven Strömqvist, and Per Henning Uppstad. 2008. Det Flerspråklige Mennesket: En Grunnbok om Skriftspråklæring. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

| Grammatical Repertoire: Relative Number of Texts with the Grammatical Feature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grammatical Feature | MP2 Outdoor Activities | MP2 Magical Hat | MP4 Outdoor Activities | MP4 Magical Hat |

| T-units | 74.32% (110/148) | 70.75% (104/147) | 89.84% (115/128) | 95.50% (106/111) |

| Phrases | 19.59% (29/148) | 31.97% (47/147) | 35.16% (45/128) | 44.14% (49/111) |

| Nominal Clauses | 6.76% (10/148) | 14.97% (22/147) | 17.19% (22/128) | 26.13% (29/111) |

| Adverbial Clauses | 22.97% (34/148) | 20.41% (20/147) | 43.75% (56/128) | 41.44% (46/111) |

| Relative Clauses | 7.43% (11/148) | 19.73% (29/147) | 20.31% (26/128) | 42.34% (47/111) |

| Infinitive Clauses | 58.78% (87/148) | 4.76% (7/147) | 82.81% (106/128) | 22.52% (25/111) |

| Additive Connections | 25% (37/148) | 32.65% (48/147) | 33.59% (43/128) | 51.35% (57/111) |

| Formal Subjects | 12.84% (19/148) | 10.88% (16/147) | 27.34% (35/128) | 28.83% (32/111) |

| Topicalisations | 20.27% (30/148) | 42.86% (63/147) | 34.38% (44/128) | 65.77% (73/111) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nygård, M.; Hundal, A.K. Features of Grammatical Writing Competence among Early Writers in a Norwegian School Context. Languages 2024, 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9010029

Nygård M, Hundal AK. Features of Grammatical Writing Competence among Early Writers in a Norwegian School Context. Languages. 2024; 9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleNygård, Mari, and Anne Kathrine Hundal. 2024. "Features of Grammatical Writing Competence among Early Writers in a Norwegian School Context" Languages 9, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9010029

APA StyleNygård, M., & Hundal, A. K. (2024). Features of Grammatical Writing Competence among Early Writers in a Norwegian School Context. Languages, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9010029