In what follows, I will argue that the differences between Spanish and Catalan stem from a more general principle: dialects of Spanish in contact with Catalan allow for definite, specific DPs in the pivot position. As such, I will take them to be full-fledged DPs whose head D hosts person, number, and gender features. More specifically, in (

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2,

Section 4.3,

Section 4.4 and

Section 4.5), I shift gears to put forth the hypothesis that existential pivots in so-called

general Spanish are assigned Partitive case, as I state in (

Section 4.1). Evidence in support of this hypothesis comes from several related facts: Romance languages with dedicated partitive pronouns pronominalize the pivot position of the existential with partitives (

Section 4.2); clitics out of existentials in Spanish are person-defective and thus

phi incomplete, even when

haber (‘to be’) bears person agreement morphemes (

Section 4.3); if person features are thought to be located in the head D, these clitics cannot be related to a full-fledged DP projection (

Section 4.4). The fact that the hypothesis of Partitive case assignment to the pivot is not ad hoc is proven by the fact that Spanish, as I argue in (

Section 4.5), has partitive pronouns with unaccusative verbs. In (

Section 4.6), syntactic variation in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan is argued to boil down to a structural condition on Partitive case assignment. Since

Belletti’s (

1987,

1988) account, Partitive case assignment is dependent on the non-definiteness of the pivot. I specifically argue that, as a consequence of contact between Spanish and Catalan, Partitive case is no longer tied to non-definiteness.

4.1. The Situation in General Spanish: Partitivity and Non-Referentiality

There seems to be wide agreement over the fact that, in Spanish, the pivot of the existential construction is not related to referential readings. The non-referentiality of the existential pivot has been accounted for in rather different ways, be it with regard to the semantics of bare noun phrases, to the grammatical category of the pivot, or in relation to case assignment. I believe a unified proposal, as the one I will develop here, to be on the right track: there is a conspiracy between semantics and case assignment that accounts for the relevant facts.

The semantics of bare noun phrases has been hypothesized to be related to either (a)

classes (or

types), which are sets of properties attributed to individuals, as in

Carlson’s (

1977, p. 59 and seq.),

Chierchia’s (

1998),

Doron’s (

2003), or

Fábregas’ (

2022) proposals, or (b) simply

properties, as put forth by

McNally (

1998,

2004). I believe the distinction between the two to be non-trivial, but irrespective of its precise semantics, what seems clear is that the pivot does not convey a determined reference, as seen in

Farkas’ works (

2000,

2002a,

2002b); it denotes neither tokens nor individuals, i.e., it does not pick up specific individuals or exemplars. It is in this sense of non-determined reference that the term

partitivity, alongside

parti-genericity, will be used here (see, among others,

Belletti 1987;

Laca 1990,

1996;

Demonte and Masullo 1999;

Schurr 2020;

Agulló 2023a).

If this hypothesis is taken to be essentially correct, we can easily break down the ungrammaticality of the samples in (16):

Neither

Juan in (16a) nor

tú (‘you’) in (16b) can be said to convey properties or sets of properties, and thus, they are ungrammatical in the pivot position. Nor can they be used in a predicative sense. Note that the ungrammaticality of (16) is robust in general Spanish, but not so in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan. Proper names and personal pronouns, in the upmost positions of

Aissen’s (

2003) Definiteness Hierarchy, are straightforwardly excluded from the pivot position in semantic terms. Given that the pivot position can only be partitive or parti-generic, both proper names and personal pronouns are barred from the position: the pivot can only pick up classes or types, and not tokens or individuals, such as

Juan (16a) or

tú (16b).

4.2. Partitive Case Assignment and Partitive Pronoun Series

The complexity of the definiteness effect, however, is not restricted to (16). On the contrary, there appears to be more to the story. I will argue, particularly, that sequences such as (16) can be ruled out if Partitive case assignment is invoked. Upon closer inspection, the hypothesis will prove both tenable and promising.

Let us assume the semantics of indefinite and bare noun phrases to be closely related to case assignment. The semantic import of case assignment need not be emphasized, as there is a long-standing tradition that links case to the semantics of the noun. The reader is referred to

Kagan (

2020) and the references cited therein. The hypothesis I will test out here crucially hinges on

Belletti’s (

1987,

1988) and

Lasnik’s (

1992) accounts; according to them, the pivot of the existential clause behaves in a similar fashion as the subject of unaccusatives in that it bears Partitive case, i.e., it does not receive a Nominative nor Accusative case.

Fábregas (

2022) and

Gràcia i Solé and Roca Urgell (

2017) also assume that Accusative case is not at work in existential sentences, as I assume here. My proposal departs from them in that I explicitly assume Partitive case assignment to be at work in existentials. A distinction was drawn in

Chomsky (

1981) between an

inherent case, associated with theta-marking, and

structural case, which independent of theta-marking and is construction-dependent. The question shall be raised as to whether Partitive case is inherent or structural, but I believe that this issue would take us rather far afield. Let us only briefly touch upon it.

Belletti (

1987,

1988) takes Partitive case to be inherent (cfr.

Eguzkitza and Kaiser 1999), but

Lasnik (

1992),

Vainikka and Maling (

1996), and

Kiparsky (

1998) have casted some doubts on the assumption. Partitive case in Finnish, for instance, has been related to both configurational and semantic properties (e.g.,

Lasnik 1992;

Csirmaz 2012), but I believe there remains some doubts as to whether it is inherent or structural.

Evidence in support of the fact that the pivot of the existential bears Partitive case comes in various guises. I will only be concerned, mainly for explanatory purposes, with the three following claims:

| (17) | a. | Romance languages that have a specifically partitive inventory of pronouns use it to pronominalize the pivot of the existential. |

| | b. | Western and Central Ibero-Romance recycle Accusative clitic pronouns (Rigau 1988; Longa et al. 1996, 1998) are partitives. As such, these pronouns are endowed with number features, but not person features. |

| | c. | These accusative-as-partitives pronouns are not ad hoc stipulations for existentials, as they can be found in some unaccusative constructions. |

If the claims in (17) are on the right track, as I will argue, the hypothesis that the pivot position of the existential is assigned Partitive case would fare better than other alternative hypothesis.

The claims in (17a) and (17b) shall be reviewed jointly. Romance Languages can be said to belong to one of the two following classes: (a) languages with dedicated partitive pronoun series (e.g., Catalan, Aragonese, Italian, French, and Occitan) and (b) languages without dedicated partitive pronouns (e.g., Galician, Portuguese, Spanish, and Rumanian) (cfr., specially,

Kabatek and Pusch 2011). Let us concentrate on Catalan’s partitive pronouns, as those italicized in (18), and Spanish’s accusative-as-partitive pronouns, as in (19):

| (18) | a. | N’hi ha | que | diuen | que | els | redacta | ell. |

| | | part-loc is | that | say | that | cl.acc-3pl | writes | he |

| | | ‘There are those that say that he writes them himself.’ (CTILC 1967) |

| | b. | N’hi ha | que | pretenen | que | és | viu. | |

| | | part-loc is | that | pretend | that | is | alive | |

| | | ‘There are those that pretend he is alive.’ (CTILC 1969) |

| (19) | a. | Los | hay | que | nacen | con | estrella. | |

| | | cl.acc-3pl | is | that | born | with | star. | |

| | | ‘There are those that are born with a star.’ (CORPES XXI, Spain) |

| | b. | Los | hay | que | son | guardias | de | tráfico. |

| | | cl.acc-3pl | is | that | are | guard | of | traffic. |

| | | ‘There are those that are traffic guards.’ |

The data in (18) and (19) are descriptively simple but theoretically relevant. Catalan resorts to the dedicated partitive clitic

en / n’ to pronominalize the pivot of the existential sentences. There is thought to be a tendency to substitute the partitive in these cases for the accusative form, but not in all contexts (e.g.,

Bartra 1987;

Jané 2001). Spanish, on the contrary, uses morphologically accusative forms (and even the covert pronoun; see

De Benito Moreno 2016;

Agulló 2022) to pronominalize the pivot. As the inquiry proceeds, I will demonstrate that the term

accusative does not improve matters here; I will argue that proforms, such as as those in (19), are best regarded as partitives, on account of its φ-feature defectiveness.

4.3. Phi-Feature (in)Completeness and Types of Clitics

The samples in (19), in fact, are potential counterarguments to

Belletti’s (

1988) and

Lasnik’s (

1992) hypothesis that the pivot receives Partitive case; if these forms are morphologically accusative, why they should be instances of Partitive case? As an anonymous reviewer gently pointed out, if the assumption is not made to follow from more general principles of grammar, it seems somewhat unnatural or arbitrary. The answer to this lies, I believe, in the φ-feature defectiveness of the Spanish forms in (19). Note that, if we take these forms to be purely accusative, we are left with no explanation of the person asymmetry in (20):

| (20) | a. | A | los | españoles | se | {los / os / nos} | ve | felices. |

| | | dom | the | spaniards | imp | {3pl / 2pl / 1pl}acc | see | happy |

| | | ‘One can see {you / us / they} Spaniards are happy.’ |

| | b. | {Los / *Os / *Nos} | hay | felices. |

| | | {3pl / 2pl / 1pl}acc | is | happy |

| | | ‘There are some {of them / of you / of us} happy.’ |

It is generally agreed upon that accusative clitics can agree in first, second, and third person, as in (20a). I will now remain neutral as to whether cases like (20a) are instances of

anti-agreement in the sense of

Boeckx (

2008) or of

unagreement in the sense of

Rivero (

2004), as the decision does not hinge on the validity of the argument developed here.

Los españoles (‘the Spaniards’) in (20a) can trigger first-, second-, and third-person agreement in the clitic, contrary to what happens in (20b) (see

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2006,

2007a,

2007b,

2019;

Gràcia i Solé and Roca Urgell 2017 for similar data); the clitic related to the pivot can only bear third-person agreement. The clitic pronoun in (20b) can hence be regarded as φ-feature-defective or incomplete; it lacks both first- and second-person agreements. Digressing briefly, φ-feature defectiveness or incompleteness makes clitics out of existentials bear close resemblance to so-called

predicative clitics in Spanish of the sort, as illustrated in (21), which are also φ-feature-defective:

| (21) | a. | Los | otros | no | siempre | lo | son. |

| | | the-m-pl | others | neg | always | cl.acc | are |

| | | ‘Not always the others are so.’ (CORPES XXI, Mexico) |

| | b. | Son | pecados | –claro | que | los | son–. |

| | | are | sins | of course | that | cl.acc-pl | are |

| | | ‘Those are sins; of course they are so.’ (CORPES XXI, Dominican Republic) |

| | c. | La | cordillera | no | es | nadie, | pero |

| | | the-f | range | neg | is | nobody | but |

| | | todos | la | somos. | | | |

| | | all | cl.acc-f | are | | | |

| | | ‘The range is nobody, but we all are the range.’ (CORPES XXI, Chile) |

The clitics in (21) pronominalize a predicate, but, quite generally, the person, number, and gender features are stripped away, as in (21a); the neuter clitic lo is used no matter the person, number, or gender specification of the predicate subject. However, there can be seen to be two variation phenomena at stake. (a) In certain varieties of Spanish, mainly Caribbean and Central, the predicative clitic can retain number features, as shown in (21b): the clitic los agrees in number with pecados (‘sins’), contrary to expectation. (b) Mainly in Chilean Spanish, the predicative clitic can also bear gender agreement, as seen in (21c); the clitic la agrees in gender with cordillera (‘mountain range’). Predicative clitics are generally held to be neuter- and thus φ-feature-defective, as seen in (21a); the proform is void of person, number, or gender features. φ-feature enrichment can take place, and predicative clitics may acquire number feature agreement, as seen in (21b), or gender feature agreement, as seen in (21c).

Defectivity or incompleteness as regards φ features, hence, holds across different types of clitics, but to varying degrees: (a) clitics out of existentials, which are person-defective, and (b) predicative clitics, which are person-, number-, and gender-defective. φ-feature enrichment can take place in the latter class, as predicative clitics may acquire number and gender features in certain varieties. As should be noted, φ-feature defectivity in clitics out of existentials holds regardless of the dialectal variety: no φ-feature enrichment can take place. Let us build upon this claim.

Haber (‘to be’) existential sentences are generally held to display third-person agreement by default: the pivot position, be it singular or plural, does not trigger number agreement. Plural agreement is, nevertheless, widely attested and is even more frequent than

par default singular agreement in some varieties (see, among others,

Claes 2014,

2016;

Pato 2016). In some varieties, even person agreement with existential

haber (‘to be’) is found. The reader is referred to

Castillo Lluch and Octavio de Toledo y Huerta (

2016) for essential data and to

Gràcia i Solé and Roca Urgell (

2017) and

Fábregas (

2022) for some theoretical analyses. The basic descriptive data are shown in (22):

| (22) | a. | Aquí | habemos | seis | vecinos. | | |

| | | here | are | six | neighbors | | |

| | | ‘There are six of us neighbors.’ |

| | | (COSER, Casas de Soto (Valencia) COSER-4308_01) |

| | b. | Habemos | poca | gente. | | | |

| | | are | few | people | | | |

| | | ‘There are few people among us.’ |

| | | (COSER, Mahíde (Zamora) COSER-4617_01) |

| (23) | a. | Imbéciles | los | habemos | en | todos | lados. |

| | | idiots | cl.acc-m-pl | are | in | every | places |

| | | ‘Idiots, there are some of us everywhere.’ (Corpus del Español, Uruguay) |

| | b. | Los | habemos | mucho | más | bestias. | |

| | | cl.acc-m-pl | are | much | more | savage | |

| | | ‘There are some of us that are much more savage.’ |

As it seems,

seis vecinos (‘six neighbors’) in (22a) or

poca gente (‘few people’) in (22b) trigger both number and person agreement. That being the case, the definiteness effect seems to hold at any rate (

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2006;

Fábregas 2022); only indefinite pivots are allowed. Person agreement, hence, cannot be said to lift the definiteness effect. Essential in this respect is that, whenever the pivot of the existential is pronominalized, the clitic does not show person agreement, as shown in (23); only the three-person-by-default

los may be used. Thus, the ungrammaticality of first and second personal pronouns, as illustrated in (20b), remains, no matter the person agreement with the verb. I believe the φ-feature incompleteness of the clitic pronoun in (19, 20b, 23) to be strong evidence in support of the hypothesis that these clitics belong to a different class of clitics. Ultimately, differences across classes of clitics will be shown to be derived from the Partitive case assignment hypothesis.

4.4. Layers in the DP: D as the Locus of Person

Noteworthy is the fact that, both in clitics out of existentials (20b) and in predicative clitics (21), person agreement seems to be highly restrictive. In fact, person agreement will be taken here to be at the core of the contrast between standard accusative clitics, as in (20a), and clitics out of existentials, as in (19, 20b, 23). I believe the asymmetry in person features in (20) to be essential for the architecture of the grammar; by no means is it merely accidental or hazardous. With this in mind, it is safe to conclude that Spanish clitics out of existentials are not endowed (

person) features, nor are predicative clitics of the sort illustrated in (21). I will take this gap as evidence in support of the following diagnosis: clitics out of existentials belong to a different class and are not just person-stripped accusatives. I take this class to be the Partitive series, which, similarly to (18a), does not show person agreement. I am using the term

partitive—and will use this term henceforth—much along the line of

Cardinaletti and Giusti’s (

1992,

2006) use of

quantitative (see also

Zamparelli 2000, §4.2.3); the clitic is a

subnominal clitic, following

Pollock (

1998), that pronominalizes not a DP, but lower layers of it. In that sense, it can be regarded as quantificational. The reasons behind my decision to assign different structural layers to each type of pronoun are multiple.

Fábregas (

2022), for instance, takes the pivot of the existential to be a Noun Phrase, which is a proposal I believe to be essentially correct. To sharpen the issues here, let us assume that different positions within the nominal phrase are associated with different interpretations, i.e.,

Longobardi’s (

1994)

topology within the nominal domain. It has come to be known that referentiality and predominantly, Person features are closely correlated to the DP projection (see, among others,

Longobardi 1994;

Martin et al. 2021).

Longobardi (

2008) and

Bernstein (

2008) have specifically argued for the functional head D(eterminer) to be the locus of person features. If person features are, in fact, located in D, it is clear that clitics out of existentials, along with predicative clitics, cannot be related to the same layer as fully fledged personal pronouns (i.e., those in (20a)). Recall that, in relation to (19, 20b, 23), it was derived that clitics out of existentials are not provided with person features, nor are predicative clitics in (21). That is, they lack person features and are thus φ-feature incomplete. If this lack of person features is taken to be the basis of a configurational diagnosis, as in the work by

Martin et al. (

2021), clitics out of existentials and predicative clitics cannot be related to a DP position. To put it differently, they are not related to the highest layers of the DP, as that is where person features are located.

Zamparelli (

2000, §1.1.4.2) noted similar contrasts for Italian and also attributed different layers to (a) object clitic pronouns, (b) predicative

lo, and (c) partitive

ne.

Let us recapitulate what has been tackled thus far. The claims in (17a) and (17b) have been used in support of the hypothesis that clitics out of existential clauses in Spanish behave like partitive pronouns in several respects: (i) they are used to pronominalize the pivot of the existential; (ii) they are void of person features, much like predicative clitics; and (iii) they are presumably related to a non-DP position, that is, to a Noun Phrase position, also lacking person features.

4.5. Partitive Pronouns in Spanish with Unaccusative Predicates

The validity of the claims in (17a) and (17b) has been argued to stem from different areas of grammar. There remains to account for the claim in (17c). Note that, if the claim in (17c) proves true, the partitive nature of clitics in existentials would by no means be an ad hoc theoretical move. A complete analysis of the emergence of a class of

unaccusative partitive clitics in Spanish, as I will hereinafter refer to them, lies far beyond the scope of this paper. I refer the reader to

Agulló (

forthcoming), where some of these ideas are fully developed. Let us review, at least, the basic empirical support for the claim in (17c). The data suggest that a close resemblance can be traced between partitive pronouns of the sort in (18) (and, by extension, (19)) and unaccusative partitive pronouns, such as those italicized in (24) (taken from

Agulló, forthcoming):

| (24) | a. | Los | existimos | que | buscamos | respetar | las | normas |

| | | cl.acc-m-pl | exist | that | search | respect | the | regulations |

| | | de | tráfico. | | | | | |

| | | of | traffic | | | | | |

| | | ‘There are some of us that respect traffic regulations.’ (X (formerly Twitter), @LaPatataComuni1, 9/04/2023) |

| | b. | Los | estamos | que | nos | gusta | echar | unas |

| | | cl.acc-m-pl | are | that | cl.dat.1-pl | like | throw | some |

| | | risas. | | | | | | |

| | | laughs | | | | | | |

| | | ‘There are some of us that like to laugh.’ (X (formerly Twitter), @Naxo82026228, 20/11/2022) |

| | c. | De | esos | los | abundan | por | ahí | |

| | | of | them | cl.acc-m-pl | abound | for | there | |

| | | ‘Of that kind, they abound everywhere.’ (X (formerly Twitter), @PabloGa98541569, 3/12/2022) |

The fact that verbs such as

existir (‘to exist’), presentative

estar (‘to be’), or

abundar (‘to abound’) belong to the unaccusative class, as formulated in

Perlmutter (

1978) and

Burzio (

1986), is clear from a bundle of aspectual, syntactic, and semantic properties: (i) unaccusative verbs allow for bare noun phrases as postposed subjects (

Torrego 1989;

Contreras 1996); (ii) some unaccusatives admit that adjectives ending in

-ble, such as

variable (‘variable’), are contrary to unergatives, which generally reject them (cfr. the ungrammaticality of

nadable ‘swimmable’) (

De Miguel 1986a,

1986b); and (iii) unaccusatives are low-agentivity predicates (

Perlmutter 1978;

Pustejovsky 1995).

Existir (‘to exist’), for instance, has been generally held to be an unaccusative predicate (e.g.,

Batiukova 2004;

López Ferrero 2008;

Jaque Hidalgo 2010). The verbs in (24) are clearly imperfective, even though unaccusatives have been widely linked to perfectivity (e.g.,

Bosque 1990, p. 170 and seq.;

Hernanz 1991;

De Miguel 1992).

The data in (24) seem puzzling, at least prima facie, due to several reasons. The syntactic subject of unaccusatives behaves similarly to a semantic object (see, among many others,

Mendikoetxea 1999;

Campos 1999;

Batiukova 2004;

Alexiadou et al. 2004;

Baños 2015;

Bosque and Gutiérrez-Rexach 2009), but it triggers both person and number agreement with its verb. It is thus safe to conclude that the argument of the unaccusative predicates in (24) occupies the subject position. That being the case, how is the pronominalization of the subject to be accounted for? To put it differently, if the subject of the examples in (24) triggers number and person agreement, how is it that it can be pronominalized? If the unstressed pronouns in (24) were to be ascribed to the accusative pronoun series in Spanish, we would expect neither person nor number agreement with the verb. Invoking object agreement in cases like (24) would not improve matters here; a lack thereof in Spanish seems clear, and it would be an ad hoc or arbitrary theoretical move.

A possible solution to this paradox lies in a well-known fact about unaccusative verbs in Romance languages: in languages that have explicitly partitive pronoun series (recall the claim in (17a)), the partitive pronoun can be used to pronominalize the subject of the unaccusative verb (

Belletti 1979;

Belletti and Rizzi 1981;

Bentley 2004,

2006, §6. 3). The relevant data are shown in (25) with examples from Italian (25a), French (25b), and Catalan (25c):

| (25) | a. | Ne | sono | arrivate | due. | | | |

| | | cl.part | are | arrived | two | | | |

| | | ‘There arrived two.’ |

| | | (Example taken from Bentley 2006, p. 253) |

| | b. | Il | en | est | allé | beaucoup | à | Venise. |

| | | expl | cl.part | are | gone | lots | to | Venise |

| | | ‘There have gone many to Venise.’ |

| | | (Example taken from Manente 2008, his (110c)) |

| | c. | Avui | ja | no | en | surten. | | |

| | | Today | already | not | cl.part | | | |

| | | ‘Today, they no longer come out.’ |

| | | (Example taken from Todolì 2002, p. 1376) |

Predicates like

arrivare (‘to arrive’) in (25a),

aller (‘to go’) in (25b), and

surtir (‘to come out’) in (25c) are proper unaccusatives. As such, their internal arguments can be pronominalized with the corresponding partitive pronouns: It.,

ne; Fr.,

en; and Cat.,

en/n’. Recall that the puzzling nature of the Spanish examples in (24) stemmed from the fact that, regardless of the pronoun, the argument anyhow triggers number and person agreement with the verb. The same situation holds in the examples in (25); the internal argument is

ne-pronominalized and, at all events, it triggers number and person agreement. I will take, from now on, the pronouns in the examples in (24) and (25) to be of the same sort and to belong to the φ-feature-defective class of partitive pronouns. The hypothesis, which still needs to be fully unfolded, awaits further research, but I will regard it here as a diagnosis that a more general mechanism seems to be at work: the pivot, as suggested by

Belletti (

1988) and

Lasnik (

1992), bears Partitive case and is thus φ-feature-defective.

4.6. Microcontact and Phi-Feature Enrichment

Throughout this paper, I have tacitly assumed that the φ-feature defectiveness of the pivot is a consequence of it being assigned Partitive case. The assumption is on no account trivial or cursorily, as it ultimately hinges on the nature of the definiteness effect and the principles governing case assignment and interpretation. The account of the effect I have worked out here bears close resemblance to other syntactic accounts of the definiteness effect, along the lines of

Safir (

1982),

Longa et al. (

1996,

1998), and

Belletti (

1987,

1988). The basic intuition underlying these accounts is that configurational principles (i.e., namely, but not exclusively, case assignment), such as syntactic chains under

Safir’s (

1982) purview or

Belletti’s (

1987,

1988) Partitive case assignment, are at the core of the definiteness effect.

The φ-feature incompleteness of the pivot position of the existential, which is, under my proposal, a side consequence of Partitive case assignment, is not new in the literature on the definiteness effect. I will flesh out

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo’s (

2006,

2007a,

2007b,

2019) proposal, whose predictions I believe to be not only accurate but also quite promising for Spanish.

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo’s works (

2006,

2007a,

2007b,

2019) (drawing heavily on

Rigau 1988,

1991,

1993,

1997) have convincingly argued that, in Spanish, pivots of existential

haber (‘to be’) are not endowed with person features. The head of the small

vP, which case-checks the nominal under the current assumptions, only has number features. These ideas can be easily argued to account for the restriction on person features that seems to hold in the pivot position of existential

haber (‘to be’) in Spanish. In fact, proper nouns, such as those in (26a), or personal pronouns, such as those in (26b), are banned in the pivot position (see also

Agulló, forthcoming):

A restriction on person features, as illustrated in (26), would bar personal pivots, mainly items in the leftmost positions of

Aissen’s (

2003) Definiteness Scale. It should be born in mind that, in standard definiteness hierarchies (e.g.,

Aissen 2003; see, particularly,

von Heusinger and Kaiser 2003,

2007, for Spanish), proper names, such as those in (26a), and personal pronouns, such as those in (26b), are thought to occupy the highest positions of the hierarchy. The facts in (26) clearly show that a ban against (person) features seems to be at work. The wisdom of such an approach, however, shall be questioned.

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo’s (

2006,

2007a,

2007b,

2019) account places the theoretical burden of the definiteness effect on person features. As a consequence, other definite pivots without person features are left unaccounted for. Illustrative in this regard are the examples in (27):

| (27) | a. | *Hay | Sevilla. |

| | | is-loc | Seville |

| | | ‘There is Seville.’ | |

| | b. | *Había | Twitter. |

| | | there was | Twitter |

| | | ‘There was Twitter.’ | |

On no account are pivots such as

Sevilla ‘Seville’ in (27a) or

Twitter in (27b) specified for person features, and interestingly, they are equally prevented from occupying the pivot position of the existential. Note that the ungrammaticality is as robust in the samples in (27) as it is in the samples in (26), no matter the φ features involved. The examples in (27), indeed, clearly suggest a refinement of

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo’s (

2006,

2007a,

2007b,

2019) hypothesis. Nevertheless, I believe this potential refinement does not compromise the validity of the hypothesis, which remains, at least for Spanish, tenable. I will thus regard pivots of existential sentences in Spanish as φ-feature-defective, even though some additional restrictions are needed to fully account for the definiteness effect in Spanish.

In what follows, the hypothesis will be put forth that Spanish in contact with Catalan amnesties the definiteness effect. A theoretical explanation will be developed that bears upon two mechanisms: (a) Partitive case assignment and (b) φ-feature enrichment of the pivot in contact situations. The core of the hypothesis, which will be argued to follow from the data in a principled manner, can be stated as follows:

| (28) | Spanish in contact with Catalan amnesties the definiteness effect as a consequence of Partitive case no longer being linked to indefiniteness. |

Note that, under the hypothesis in (28), the definiteness effect is nothing but a descriptive artifact; its consequences are to be accounted for with resort to more general principles of grammar, as Case assignment. The hypothesis in (28) presupposes the claims listed in (29):

| (29) | a. | Partitive case is directly related to non-definiteness, as put forth by Belletti (1987, 1988). |

| | b. | The non-definiteness of the pivot is tied to the defectiveness of the DP, which also accounts for the φ-feature defectiveness of the pivot. |

The claim in (29a) directly links Partitive case assignment to non-definiteness.

Belletti (

1987,

1988) thinks of it as a sort of structural condition on Case assignment; Partitive case is genuinely assigned to non-definite noun phrases. Definite pivots are thus barred as a consequence of this structural condition on Partitive case assignment. Recall that I have taken rather independent pieces of data to support the hypothesis that the pivot position of

haber (‘to be’) existential sentences bears Partitive case: (1) the φ-feature defectiveness of clitics out of the pivot position, as seen in (19, 20b, 23); (2) the fact that the φ-feature defectiveness of the clitic out of the existential holds even in cases where

haber (‘to be’) shows person agreement, as shown in (23); and (3) the ability of these φ-feature-defective clitics to pronominalize the syntactic subject of unaccusative verbs in Spanish, as in (24). It then naturally follows that the pivot position is, by default, non-definite, as required by Partitive case assignment. If, additionally, it is assumed that D is the locus of person features, along the lines of

Longobardi (

1994,

2008),

Bernstein (

2008), and

Martin et al. (

2021), the claim formulated in (29b) also follows without ad hoc theoretical moves; the pivot position of the existential is D-defective and, as a consequence, φ-defective. The φ-defectiveness of the pivot straightforwardly accounts for the absence of person features in clitics out of existentials, as argued in relation to (19, 20b, 23).

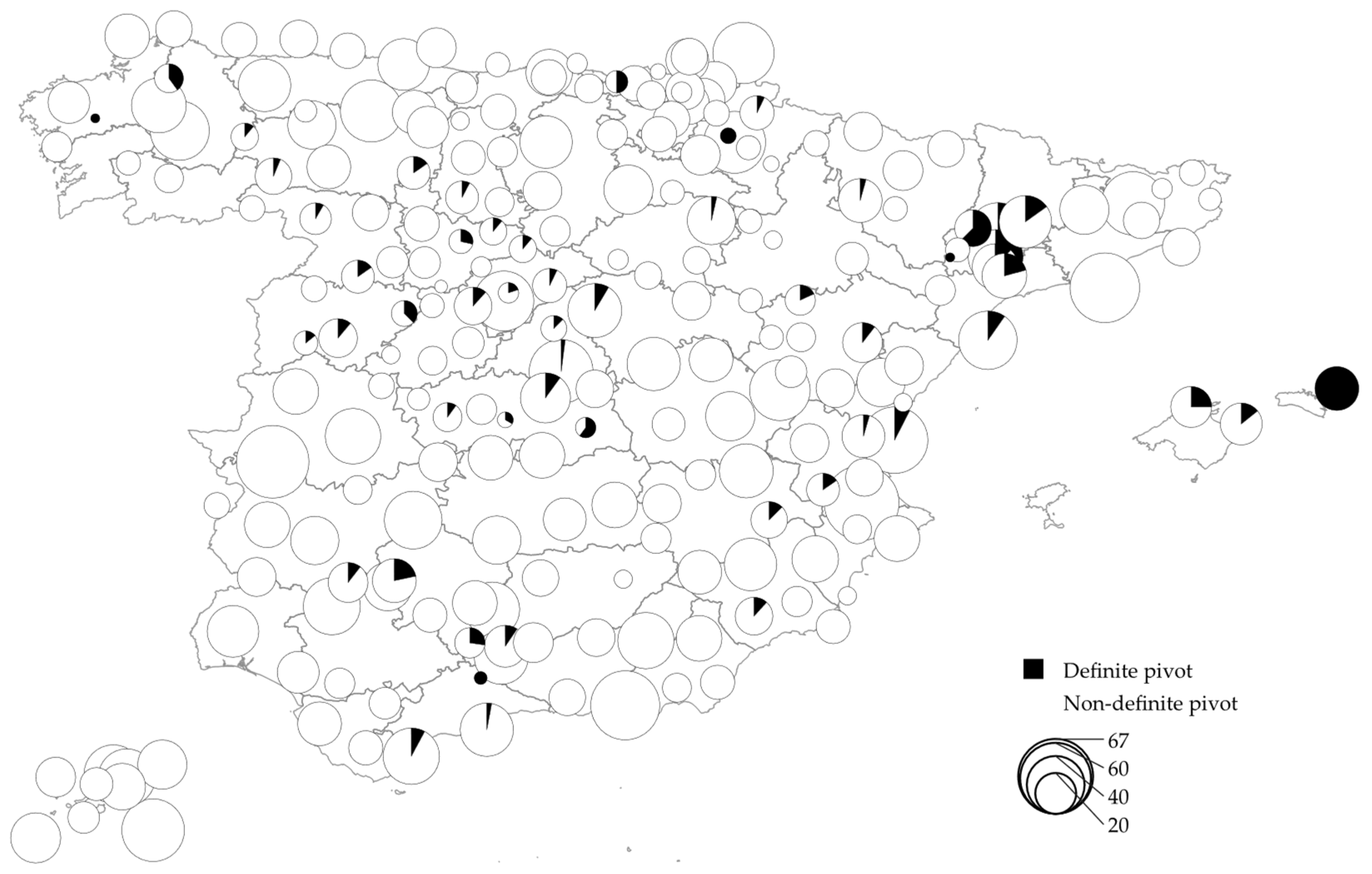

The default situation in existential sentences (i.e., Partitive case assignment and φ-feature incompleteness) has been proven to hold in general Spanish. The hypothesis, as formulated in (28) and decomposed in (29), does not seem to be fully at work in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan. In these varieties, as I will argue, Partitive case assignment is not tied to definiteness. The relevant descriptive data have been shown throughout the paper, particularly in (12), (13), and (15), but I will recast it here as evidence that these varieties allow for definite, specific pivots that are properly referential. The data shown in (30) are strong evidence in this respect:

| (30) | a. | Había | el | número | uno | caído. | | |

| | | was | the | number | one | fallen | | |

| | | ‘There was the number one fallen.’ |

| | | (Benimodo (Valencia), COSER-4306_01) |

| | b. | Aquí | había | el | tráfico | muy | grande | |

| | | here | was | the | traffic | very | big | |

| | | ‘Here, there was (the) heavy traffic.’ |

| | | (Queixas (Cabanelles) (Gerona), COSER-1707_01) |

| | c. | Había | el | camión | que | lo | esperaba. | |

| | | was | the | truck | that | it | waited | |

| | | ‘There was (the) truck that waited for him.’ |

| | | (San Climent (Mao) (Menorca), COSER-5003_01) |

| | d. | Ha | habido | los | toros | al | NO-DO | |

| | | have | been | the | bulls | in-the | NO-DO | |

| | | ‘There were the bulls on NO-DO.’ |

| | | (Vinebre (Tarragona), COSER-4011_01) |

The data in (30) illustrate what has been referred to either as

eventive existentials (

McNally 1997;

Villalba 2013) or as

presentative constructions (

De Cesare 2007;

Cruschina 2016,

2018). In these constructions, the pivot, which is referential and specific, is the subject of a stage-level predication, in the sense of

Carlson (

1977). Quite interestingly, these examples are thoroughly ungrammatical in general Spanish. I will refrain from attributing a small clause analysis

à la Stowell (

1978) to the sequences in (30), as I believe there to be several strong counterarguments to the proposal (see

Villalba 2013). What is relevant to our purpose here is that the pivot is fully identifiable, and thus specific and referential. I take this semantic interpretation to yield a structural diagnosis; the pivots in (30) are full-fledged DPs. If it is assumed that D is the locus of person features, it then naturally follows that the pivots in (30) are no longer φ-defective.

The question should be addressed as to which mechanisms underlie this case of syntactic variation. The hypothesis that existential pivots in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan are full-fledged DPs and hence equipped with φ features is specifically called into question by an anonymous reviewer. It is my belief, accordingly, that if the syntactic variation at work is not made dependent upon more general principles of grammar, the explanation seems ad hoc, arbitrary, or unmotivated. If the hypothesis in (28) and the presuppositions underlying it, as seen in (29), are thought to be essentially correct, some additional principles of syntactic variation and change have to be invoked. To put it differently, how is it that pivots in (30) are full-fledged, whereas pivots outside varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan are not?

A potential solution to this problem stems from the literature on language contact and, particularly, from the notion of

interdialect variant or form. The hypothesis will be put forth, particularly, that examples with definite, specific pivots in the existential clause of the sort in (30) are the result of contact between dialects of Spanish and dialects of Catalan. Theories on linguistic variation and change, particularly since pioneering research by

Weinrich et al. (

1968) and

Labov (

1964,

1972,

1978), have furthered our knowledge on the structural and social consequences of linguistic contact. It is generally agreed upon that, whenever grammar is subject to change, the process “entails not merely formal differences but functional differences as well” (

Harris 1984, p. 314). Contact between different languages and their dialectal varieties is generally acknowledged to lay the foundations for the emergence of (a) linguistic variants hitherto non-existent or unnoticed, (b) new dialectal varieties, and (c) the obsolescence of others (see, among many others,

Siegel 1985;

Kerswill 2013;

Cerruti and Tsiplakou 2020).

Alternatively, already in-use variants may be reallocated, i.e., recycled or used differently. New linguistic variants—so-called

interdialect variants in

Trudgill (

1989a,

1989b,

1992),

Britain (

2005), and

Almeida (

2020), among many others—can thus arise when two languages come into contact with each other. Inter-dialect variants can be thought of as “novel features not found in any of the established contributing dialects” (

Tuten 2001, p. 325). Interdialectalisms, which are, essentially, a special kind of dialect mixing, result when “speaker-learners reanalyse or rearrange forms and features of the contributing dialects” (

Tuten 2006, p. 187). Interdialect forms stem, thus, from a mixture, rearrangement, or readaptation of different features or constructions belonging to two or more dialects.

Note that, in Catalan, eventive existentials with definite and specific pivots are grammatical, as shown in the examples in (31):

| (31) | a. | Al | wharf | hi ha | la Denise | que | m’ | espera. |

| | | in-the | wharf | loc is | the Denise | that | me | awaits |

| | | ‘In the Wharf, there is Denise that waits for me.’ |

| | | (CTILC, Sagarra, Josep M. de: La ruta blava, 1964) |

| | b. | Hi ha | la Verge | dels | Dolors | asseguda. | | |

| | | loc is | the Virgin | of-the | Sorrows | seated | | |

| | | ‘There was the Virgin of Sorrows seated.’ |

| | | (CTILC, Raventós i Domènech, Jaume: Memòries d’un cabaler, 1932) |

| | c. | Hi ha | la vella | Kaa | fent rotllanes | per terra | | |

| | | loc is | the old | Kaa | doing rolls | on ground | | |

| | | ‘There was the old Kaa spinning around on the ground.’ |

| | | (CTILC, Manent, Marià (T): El llibre de la jungla, 1920) |

The structural parallelism between the examples in (30) and those in (31) is not casual. On the contrary, eventive existentials with definite pivots in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan can be accounted for in a principled way. If they are taken to be interdialect variants, the fact that these varieties allow for full-fledged DPs follows quite naturally from the hypothesis in (28). Thus stated, the hypothesis in (28) yields the following prediction: the relation of Partitive case assignment to non-definiteness, as stated in (29a), is overridden. An explanation, in fact, suggests itself: if existentials in Catalan, as those in (31), are taken to supersede the relation of Partitive assignment with non-definiteness, a lack thereof in varieties of Spanish in contact with Catalan would be a direct structural consequence of language contact.