1. Introduction

The goal of this paper is to account for inferential interrogatives with

qué in Spanish, an interrogative type with the appearance of a

wh-question, since it involves the wh-pronoun

qué ‘what’, but interpreted as an inferential yes/no question. Examples are shown in (1).

1| (1) | a. | ¿Qué | vienes, | de | la | calle?2 |

| | | what | come:2SG | from | the | street |

| | | ‘Are you coming back home (I infer)? |

| | lit. what are you coming, back from the street?’ |

| |

| | b. | ¿Qué | vas, | en coche? |

| | | what | go:2SG | by car |

| | | ‘Are you going by car (I infer)?, |

| | lit. what are you going, by car?’ |

The reason why these interrogatives are identified as split is their hybrid nature. While their initial part exhibits the

wh-pronoun

qué ‘what’ as well as falling intonation, characteristic of

wh-interrogatives, their final rising intonation and their interpretation as yes/no questions distinguish them from

wh-interrogatives. A similar interrogative pattern has been found in Catalan (

Contreras and Roca 2007) and English (

López-Cortina 2009):

More recently, these constructions have been identified as invariable

qué questions (

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo 2020a,

2020b,

2023;

Reig Alamillo 2019) and non-matching split interrogatives (

Fernández-Soriano 2021) to highlight the invariable nature of the interrogative pronoun involved in these constructions. Thus, although the tag contains a [wh] feature, it is crucially not a content

wh-pronoun, hence, it is always realized as the default

wh-word

qué at PF, unlike other split interrogative classes. This explains the asymmetries between inferential interrogatives involving the default

wh-operator

qué and other split interrogative classes involving full-fledged

wh-operators, such as

cómo ‘how’,

cuándo ‘when’, and

dónde ‘where’ (3):

| (3) | a. | ¿Qué llegaste, | anoche? | |

| | | what arrive:2SG.PERF | last.night | |

| | | ‘Did you arrive last night (I infer)?’ |

| | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿Cuándo | llegaste, | anoche? |

| | | when | arrive:2SG.PERF | last.night |

| | | ‘When did you arrive, last night?’ |

| | | | | | |

Interpretation-wise, split interrogatives in general appear to have a confirmational value, i.e., the speaker requests information to confirm a previous suspicion or intuition (

López-Cortina 2009). In this sense, these interrogatives show a strong evidential component, as also shown in

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020b,

2023), since unlike other types of confirmation interrogatives such as tag questions, the expected reply in inferential interrogatives with

qué is invariably constrained by the speaker’s inferred or presupposed answer. For example, in the reading of a sentence such as (4), the speaker makes an inference about the truth value of the proposition on the basis of indirect evidence over the content of the proposition (e.g., the speaker sees the addressee while she enters the room with shopping bags).

| (4) | ¿Qué | has | ido, | al | supermercado? |

| | what | have:2SG | gone, | to.the | supermarket |

| | ‘Are you coming from the supermarket (I infer)?, |

| | Lit. what have you gone, to the supermarket?’ |

The construction then shows an interpretative behavior similar to inferential evidentials, just as the one described by

Bhadra (

2017,

2018,

2020) for Bangla.

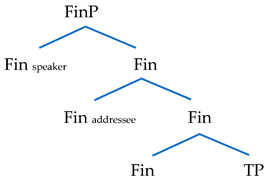

The evidential element in these constructions has an unusual Speaker-oriented interpretation, since interrogatives are typically Addressee-oriented. We propose that this unexpected interpretation follows from the interaction between the discursive elements present in the Finiteness Phrase (FinP) and the Speech Act Phrase (SAP) projections. More specifically, we propose a structure that involves the interplay between the presence of the Interrogative Flip, typical of evidential interrogatives (

Aikhenvald 2004;

San Roque et al. 2017), the evidential component present in these sentences and realized by the presence of the Speaker participant in a Fin projection (

Bhadra 2020), and the presence, above ForceP, of an SAP where the Speaker and Addressee participants are anchored to the discourse and activate the inferential and confirmational interpretations, respectively, by means of a coindexation system with the relevant clausal elements (

Bianchi 2003,

2006). This configuration explains why these interrogatives are interpreted as both inferential and confirmational (i.e., the speaker infers an answer in the tag, while the addressee is asked for full confirmation of the truth value of that inferred answer). This double discursive layer also accounts for the complex prosodic pattern typical of these constructions, in line with

Escandell-Vidal’s (

2017) proposal for interrogatives with marked prosody.

The organization of this article is as follows. In

Section 2, we list the grammatical properties displayed by inferential interrogatives with

qué that were described in previous work such as

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a). In

Section 3, we take a look at recent analyses of the construction. In

Section 4, we discuss evidentiality in the context of interrogatives.

Section 5 offers our proposal, a formal analysis based on the interaction between a Speech Act Phrase and a Finiteness Phrase.

Section 6 addresses some consequences of our proposal and links our formal analysis with the grammatical properties of inferential interrogatives. Finally, in

Section 7, we present the main conclusions.

2. Defining Characteristics of Inferential Interrogatives with qué

In this section, we review the main grammatical properties of inferential interrogatives with

qué in Spanish, as they are mentioned in previous work (e.g.,

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo 2020a), which contribute to establish crucial distinctions between these constructions and other types of interrogative clauses.

2.1. An Unexpected Intonation

Inferential interrogatives with

qué exhibit a

wh-pronoun in their initial part and falling intonation, characteristic of

wh-interrogatives. What distinguishes these interrogatives from conventional

wh-interrogatives is their final rising intonation and their interpretation as yes/no questions. This final part is frequently identified as the tag. A sentence such as (1a) above shows the intonation informally represented in (5):

| (5) | ¿Qué vienes, de la calle? |

| | ![Languages 08 00282 i001]() |

Compare with the rising intonation for the yes/no question in (6) and the falling intonation for the wh-question in (7); see

Hualde (

2005):

| (6) | ¿Vienes de la calle? |

| | ![Languages 08 00282 i002]() |

| (7) | ¿De dónde vienes? |

| | ![Languages 08 00282 i003]() |

A similar, but not identical, interrogative pattern has been found in Catalan (

Contreras and Roca 2007) and English (

López-Cortina 2009), as we indicated earlier:

| (8) | a. | Què | anirem, | al | teatre? |

| | | what | go:2PL.FUT | to.the theater |

| | | ‘What are you going, to the theater?’ |

| | | | | | | |

| | b. | Què | ho | faràs, | al | forn? |

| | | what | CL | do:2SG.FUT | to.the | oven |

| | | ‘What will you do it, in the oven?’ (Contreras and Roca 2007, p. 145 [1]) |

| | | | | | | |

| (9) | a. | What are you, crazy? |

| | b. | What is he, your lawyer? |

| | c. | What are you, looking for a raise? (López-Cortina 2009, p. 220 [1]) |

What the sentences in (8–9) share with inferential interrogatives with

qué is a complex prosodic pattern, as proposed in

Escandell-Vidal (

2017) also for other types of marked interrogatives.

2.2. The wh-Word Is Always qué ‘What’

Lorenzo (

1994),

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a,

2020b), and

Fernández-Soriano (

2021) identify crucial distinctions between the split interrogative class and inferential interrogatives with

qué. A main distinction, which we also assume, is the fact that inferential interrogatives with

qué exclusively involve the

wh-word

qué as in (10a), whereas other split interrogatives involve any content

wh-phrase, as illustrated in (10b). This is why

Lorenzo (

1994) treats

qué in inferential interrogatives as an expletive

wh-operator:

| (10) | a. | Qué | saludaste, | a | Pedro? |

| | | what | greeted:2SG | to | oven |

| | | ‘Who did you greet, Pedro?, lit. what did you greet, Pedro?’ |

| | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿A | quién saludaste, | a | Pedro? |

| | | to | who greeted:2SG | to | Pedro |

| | | ‘Who did you greet, Pedro?’ | (Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo 2020a, [19a]) |

2.3. The Operator qué Cannot Be Preceded by a Preposition

As pointed out by

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a), if the tag is a PP, the

wh-word

qué cannot be preceded by a preposition, in contrast with split questions with a content

wh-pronoun (e.g.,

dónde ‘where’), where a doubling preposition is obligatory. The contrast is shown in (11):

| (11) | a. | ¿(*De) | qué | es, de | Jaén? |

| | | from | what | is, from | Jaén |

| | | ‘Is from Jaén that she is?, lit. what is she, from Jaén? |

| | | | | |

| | b. | ¿*(De) | dónde es, | de Jaén? |

| | | from | where is, | from Jaén |

| | | ‘Is she from Jaén?’ |

The compatibility of the interrogative element with a preposition is a good test to distinguish these two types of split interrogatives, which is particularly useful when the full-fledged interrogative is qué ‘what’. It is also an indicator that the wh-word in these constructions is not a full-fledged interrogative pronoun.

2.4. The wh-Question Is Not Independent

As

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a,

2020b) discuss, inferential interrogatives with

qué cannot involve two independent interrogatives. While the initial part of split interrogatives is independent (12), that of inferential interrogatives with

qué cannot stand on its own, as seen in the ungrammaticality of (13).

3| (12) | Split questions | (13) | Inferential interrogatives |

| | a. | ¿A quién | saludaste? | | a. | *¿Qué | saludaste? |

| | | to who | greeted:2SG | | | what | greeted:2SG |

| | | ‘Who did you greet?’ | | | intended: ‘Who did you greet?’ |

| | | | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿De | dónde vienes? | | b. | *¿Qué | vienes? |

| | | from | where come:2SG | | | what | come:2SG |

| | | ‘Where do you come from?’ | | | intended: ‘Where are you coming from?’ |

| | | | | | |

| | c. | ¿Dónde | vas? | | c. | *¿Qué | vas? |

| | | where | go:2SG | | | what | go:2SG |

| | | ‘Where are you going?’ | | | intended: ‘How are you going? |

This contrast is an indication that inferential interrogatives with

qué are monoclausal. We develop this point further below in

Section 3.3.

2.5. Inferential Interrogatives with qué Accept Tags Other than DP

Also reported in

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a), only inferential interrogatives with

qué may be equivalent to a true yes/no question, and they may accept tags beyond the DP level, as seen in (14), with a DP followed by a comitative PP. Other split questions are more restricted in this sense.

| (14) | a. | ¿Qué | ha | ido, | Ana contigo? |

| | | what | have:3SG | gone | Ana with.you |

| | | ‘Did Ana go with you (I infer)?’ |

| | | | | | |

| | b. | *¿Quién | ha | ido, | Ana contigo? |

| | | who | have:3SG | gone | Ana with.you |

| | | Intended: who went, Ana with you? |

| | | | | | |

| | | Cf., | ¿ha | ido | Ana contigo? |

| | | | have:3SG | gone | Ana with.you |

| | | | ‘Has Ana gone with you?’ |

2.6. Inferential Interrogatives with qué Have a Confirmational Flavor

Split interrogatives in general have a confirmational value, in the sense that the speaker requests the addressee to confirm a previous suspicion or intuition in their expected answer (

López-Cortina 2009). This confirmational flavor is present in other types of interrogatives. For example, an inference based on evidentiality is precisely what we find in constructions such as

Bianchi and Cruschina’s (

2019) polar interrogatives with fronted focus in English, also found in Spanish:

This type of polar question has a confirmational value, which can only be understood if produced in a context that can be used to trigger the evidential reading. For example, the sentences in (15) are interpreted as confirmational if uttered when we enter the kitchen and see somebody preparing the necessary ingredients for the specific dish.

Interestingly, inferential interrogatives with

qué show a behavior that is similar to inferential evidentials crosslinguistically.

Bhadra (

2018) analyzes the evidential marker

naki in Bangla as a case of indirect evidence (

Rooryck 2001) that can occur in different types of sentences, including interrogatives:

Bhadra (

2018) claims that one of the roles of this particle is to ask for confirmation of the positive answer expected after inferring the truth-value from indirect evidence. In (17), we find another clear example from Bangla where the evidential marker

naki indicates that some indirect evidence proves that what is asserted is true.

| (17) | Context: Ram knows that Mina has been thinking about going to America for a while now but has not made up her mind yet. Today, he suddenly sees several of her suitcases, all packed, sitting out in the hall and asks her brother: |

| | | | |

| | Mina amerika chol-e | ja-cche | naki? |

| | Mina America go-IMPERF | go-3SG.PRES.PROGR | NAKI |

| | ‘(Given what I inferred) Mina is going away to America (is it true)?’ |

| | | | (Bhadra 2018, p. 2[3]) |

What is interesting about this particle is that this interpretation is only available if it appears in an interrogative sentence. If it appears in a declarative sentence, the interpretation of the particle does not have confirmation value, as seen in (18), which has a strictly reportative value.

| (18) | Context: Ram heard a rumor about his neighbor that he is now reporting to his friend Sita: |

| | | | | |

| | Mina naki | amerika chol-e | ja-cche | |

| | Mina NAKI | America go-IMPERF | go-3SG.PRES.PROG |

| | ‘Mina is going away to America (I hear)’ |

| | | | | (Bhadra 2018, p. 2[2]) |

The behavior of this particle is evidence of the projection of evidentiality material in syntax, as well as its composition interpretation, as will be argued in this paper.

Section 5 and

Section 6 below further develop the idea that evidentiality projects in syntax.

2.7. Both Types of Split Questions May Be Preceded by Topics

Finally, both types of split questions allow the

wh-word to be preceded by topics. Both sentences in (19) allow the preceding topic

el helado ‘the ice-cream’. As just seen, the sentence in (19a) is the inferential interrogative with

qué, disallowing a preceding preposition, in contrast with the split interrogative in (19b), which does allow it:

| (19) | a. | Inferential interrogative with qué |

| | | ¿El | helado(,) | (*de) | qué es, de chocolate? |

| | | the ice.cream | of | what is, of chocolate |

| | | ‘Is the ice-cream chocolate ice-cream (I infer)?’ |

| | | | | | |

| | b. | Split question |

| | | ¿El | helado(,) | de qué | es, de chocolate? |

| | | the ice.cream | of what | is of chocolate |

| | | ‘Is the ice-cream chocolate ice-cream (I infer)?’ |

In the next section, we show recent analyses of the construction, divided between monoclausal and biclausal approaches.

3. Previous Recent Analyses

3.1. A Monoclausal Analysis

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a) suggest an analysis based on a low FocP (à la

Belletti 2001,

2005), whereby the interrogative operator

qué is base-generated in situ. More precisely, it originates in spec-CP, not involving any kind of movement. For the sentence in (20), the authors provide the analysis in (21):

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo ’s analysis is based on VP-movement to spec-FocP. However, this is problematic in cases in which we have a complex verb (with auxiliaries), since it is the auxiliary part that occupies T, whereas V remains lower. In such cases, we would obtain the ordering Qué Aux Subj VP: *¿Qué has tú venido, en bicicleta?, contrary to facts. In particular, if the finite auxiliary is in T and then moves to C (as the lexical V vienes in (21)), the outcome involves the ordering Aux+Subject+VP, which is completely ill-formed.

Also, embedding of the inferential interrogative appears to be possible, at least in our dialect, which suggests that the operator undergoes long-distance movement to the matrix CP:

4| (22) | Long-distance movement |

| | a. | ¿Qué | te | fastidia | que venga, | el | sábado? |

| | | what | CL:2SG | annoy:3SG that come:1SG, | the | Saturday |

| | | ‘Do you regret that I’m visiting on Saturday (I infer)?’ |

| | | | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿Qué | no | te | viene bien que venga, | el | sábado? |

| | | what | NEG CL:2SG | come:3SG well that come:1SG, | the | Saturday |

| | | ‘Isn’t it good for you that I’m coming Saturday (I infer)?’ |

In addition, as shown by

López-Cortina (

2009), some Spanish varieties allow the interrogative pronoun

qué to appear in situ in these constructions, and the same is found in English. Compare (23) and (24):

| (23) | a. | Ecuadorian and Chilean Spanish |

| | | Vas | qué, | en tren? |

| | | go:2SG | what | on train? |

| | | ‘You go what, by train?’ |

| | b. | Some varieties of American English |

| | | %You are going what, by train? |

| | | | | |

| (24) | a. | ¿Qué vas, en tren? |

| | b. | What are you going, by train? |

An analysis where the operator is base-generated is inconsistent with this data, as the alternation between in situ and

wh-first constructions favor a movement analysis.

5 If the operator occupies [Spec, CP] from the beginning, the connection between (23) and (24) is lost. Note that their interpretation is identical, and the only difference is syntactic, i.e., no movement of

qué in (23), and movement of this operator in (24).

The analysis proposed by

López-Cortina (

2009) is based on the projection of a Confirmation Phrase (ConfP), whose complement is the tag of the interrogative and whose specifier is the operator

qué. In (25), we offer the analysis proposed by López-Cortina for sentences such as (24a):

| (25) | ![Languages 08 00282 i005]() |

Depending on the variety of Spanish, the operator will undergo wh-movement or remain in its original position.

This analysis captures the confirmational meaning of these interrogatives, but it fails to account for the focus interpretation of the tag. Actually, as is clear from the derivation in (25), no focus interpretation is taken into account by López-Cortina. In turn,

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a) propose that the tag is focused, as seen in their analysis in (21). In our analysis in

Section 5, we also agree with a focus interpretation of the tag.

Below, in

Section 3.3, we also argue in favor of a monoclausal analysis. In view of the data in this section, we also propose that the interrogative operator is the result of raising, as it appears to account for the behavior of these constructions regardless of the variety.

3.2. A Biclausal Analysis

Fernández-Soriano (

2021), in turn, suggests the following biclausal analysis of her non-matching split interrogative clauses:

| (26) | [CP [Qué]i … [IP I … [FP ti [F’ Ø [CP tagj [IP… [I’ I [VP…tj]]]]]]]] |

In her analysis, the whole IP in the second clause is subject to ellipsis

à la Merchant (

2004). For Fernández-Soriano, the neuter operator

qué and the tag are contained in an FP or Speech Phrase, which she claims is the phrase corresponding to discourse phrases in monoclausal analyses. In our proposal, we will see that the evidentiality reading of these interrogatives is the consequence of projecting a Speech Act Phrase, but this will be located in the top of the tree (

Miyagawa 2017,

2022), not in the middle field.

6 In Fernández-Soriano’s analysis, the evidential interpretation is the responsibility of FP in the highest CP in (26), whereas in our proposal this interpretation is the consequence of the projection of a Speech Act Phrase on top of the only CP.

A biclausal analysis is justified for split questions with content interrogative pronouns, since both parts are independently grammatical. This is, however, not what happens in the interrogatives under study here, whose first part is not grammatical on its own, as argued by

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a,

2020b). That is, these constructions do not consist of two independent interrogatives (i.e., a

wh-interrogative followed by a yes/no question), since the

wh-portion is not a well-formed independent clause in Spanish (27).

| (27) | *¿Qué vas? |

| | what go:2SG |

| | Intended: ‘How are you traveling?, lit. what are you going? |

| | | | |

| | cf. | ¿Cómo vas? |

| | | how | go:2SG |

| | | ‘How are you going? |

The inferential interrogative in (27) cannot be used as an independent sentence, contrary to what a biclausal analysis predicts. Without a clear justification of the biclausal nature of these interrogatives, an ellipsis approach would be hard to maintain.

A monoclausal analysis where the verb moves to a focal position would be consistent with the data and the general behavior of verbs in Spanish interrogatives. We propose several tests next, which support a monoclausal analysis of inferential interrogatives with qué, while they hint at further asymmetries with other split interrogatives.

3.3. Testing the Biclausal/Monoclausal Analyses

Constituent preposing is a diagnostic associated with biclausality in Spanish (28) (examples from

Sainz-Maza Lecanda and Horn 2015), whereas clitic climbing is associated with monoclausality (29).

| (28) | a. | Biclausal |

| | | Mirando | las | olas, | andaba por la | orilla del | mar |

| | | Looking | at.the waves, walked by the | shore of.the | sea |

| | | ‘Looking at the waves, I walked by the seashore’ |

| | b. | Monoclausal |

| | | *Estudiando para los exámenes, María anda cuando puede |

| | | Studying | for | the exams | Maria walks when can:3SG |

| | | Intended: ‘Maria is studying for her exams whenever she can’ |

| (29) | Biclausal |

| | | *Se | viven | peleando |

| | | CL:3.RECIPR | live:3PL | fighting |

| | | Intended: they live fighting |

| | | Cf. Viven peleándose |

| | | | | | | | | |

Inferential interrogatives with

qué show monoclausal behavior, as they disallow constituent preposing, e.g., preposing of the tag, even with the non-elided constituent (30), and they do allow clitic climbing (31):

| (30) | *¿(Vienes) | corriendo, qué | vienes? |

| | come:2SG | running, what | come:2SG |

| | Intended: running is how you’re coming? |

| | Cf. ¿Qué vienes, corriendo? |

| (31) | ¿Qué se | lo | quiere, | comer | en la cama? |

| | what CL:REFL CL:3SG.MAS.ACC | want:3SG | eat | in the bed |

| | ‘What does he want, to eat it in the bed?’ |

| | Cf. ¿Qué quiere, comérselo en la cama? |

In (32), sentences exhibiting a complex tag are disallowed regardless of the position of the clitic, whereas the simplex tag renders the sentence grammatical:

| (32) | a. | *¿Dónde se | lo | quiere, | comer | en la cama? |

| | | where CL:RFLX CL:3SG.MAS.ACC | want:3SG | eat | in the bed |

| | | ‘Where does he want to eat it in the bed?’ |

| | b. | *¿Dónde quiere, comérselo en la cama? |

| | c. | ¿Dónde se lo quiere comer, en la cama? |

These tests support a monoclausal analysis of inferential interrogatives with

qué, and they also hint at further asymmetries with other split interrogatives. We conclude that a monoclausal analysis more accurately reflects the behavior of inferential interrogatives with

qué than a biclausal analysis. In

Section 6, we offer further arguments based on the prosodic contour of these constructions that a monoclausal analysis more accurately reflects the behavior of inferential interrogatives with

qué than a biclausal analysis.

4. Evidentiality in Inferential Interrogatives with qué

Evidentiality has been extensively studied in languages with morphological evidential particles (

Aikhenvald and Dixon 2003;

Aikhenvald 2004). In these languages, evidential particles explicitly mark the source of information in a number of ways. According to

Aikhenvald (

2004), these particles vary in different languages, and they may encode that the information was reported by someone else, that the information was experienced first-hand by the speaker, sometimes visually, sometimes non-visually (e.g., through hearing or smelling), or by means of inference. Typically, evidential markers are obligatory and morphologically contrasted, depending on the type of source they specifically encode, as seen in (33) for Tariana, an Arawakan language spoken in Brazilian Amazon:

| (33) | Tariana (Arawakan) |

| | a. | Visual evidential (recent past) -ka |

| | | Juse iɾida | di-manika-ka |

| | | José football 3SG.NF-play-REC.P.VIS |

| | | ‘José has played football (we saw it)’ |

| | | | |

| | b. | Non-visual evidential (recent past) -mahka |

| | | Juse iɾida | di-manika-mahka |

| | | José football 3SG.NF-play-REC.P.NONVIS |

| | | ‘José has played football (we heard it)’ |

| | | | |

| | c. | Inferred evidential (recent past) -nihka |

| | | Juse iɾida | di-manika-nihka |

| | | José football 3SG.NF-play-REC.P.INFER |

| | | ‘José has played football (we infer it from visual evidence)’ |

| | | | |

| | d. | Assumed evidential (recent past) -sika |

| | | Juse iɾida | di-manika-sika |

| | | José football 3SG.NF-play-REC.P.ASSUM |

| | | ‘José has played football (we assume this on the basis of what we already know)’ |

| | | | |

| | e. | Reported evidential (recent past) -pidaka |

| | | Juse iɾida | di-manika-pidaka |

| | | José football 3SG.NF-play-REC.P.REP |

| | | ‘José has played football (we were told)’ |

| | | (Aikhenvald 2004, p. 3 [1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5]) |

Some authors have specifically explored the presence of evidential particles in interrogatives (

Speas and Tenny 2003;

San Roque et al. 2017;

Bhadra 2017,

2018,

2020). According to

San Roque et al. (

2017), evidentials both provide information about the utterance and associate that information with the speech act participants, thanks to their perspectivizing function. For these authors, interrogative utterances also marked for evidentiality combine two facets of the expression of epistemicity in language: while evidentials express the source of information one (e.g., a discourse participant) has for a given proposition, interrogatives involve the speech act of questioning, by means of which information is requested that is unknown to the speaker.

According to these authors, this double function seems paradoxical, as one typically asks about things one knows little about. In other words, it would be a paradox for the same discourse participant to both request information about something and indicate the source of their knowledge. In fact, evidentials are incompatible or restricted with interrogatives in a number of languages (

Aikhenvald 2004).

In languages in which evidentials are permitted along with interrogatives, identical evidential markers may contribute contrasted information depending on whether they appear in declaratives or interrogatives (

San Roque et al. 2017;

Bhadra 2017,

2018,

2020), which suggests that the interpretation of evidential particles is determined compositionally.

In this section, we discuss previous work on evidentials in interrogatives, paying special attention to the contribution that evidentials make to the syntactic composition of interrogatives, particularly the left-most left periphery. We also discuss how the presence of evidential material impacts the interpretation and markedness of interrogatives as well as the participants’ point of view.

4.1. Change of Perspective in Interrogatives and the Interrogative Flip in Inferential Interrogatives

A general characteristic exhibited by interrogatives with morphologically overt evidentials is the presence of the

Interrogative Flip (

Tenny and Speas 2004;

San Roque et al. 2017), a phenomenon by means of which the same evidential particle takes the speaker perspective in a declarative sentence, while it takes the perspective of the addressee in an interrogative. In the example in (34) from Duna, a Papuan language, the evidential affix

yarua is addressee-oriented in the interrogative in (34A), but the same affix is speaker-oriented in the answer (a declarative sentence) in (34B):

| (34) | Duna (Papuan) | |

| | A: | ko | roro-yarua=pe | |

| | | 2SG hot-SENS=INTER | |

| | | ‘Are you hot (you feel)? | |

| | B: | no | roro-yarua | |

| | | 1SG hot-SENS | |

| | | ‘I am hot (I feel)’ | (San Roque et al. 2017 [1]) |

Besides Duna, this switch in perspective is obligatory in many world languages, including English (

Speas and Tenny 2003;

Tenny and Speas 2004), Japanese (

Tenny 2006), Cuzco Quechua (

Faller 2002), and Cheyenne (

Murray 2010), to name a few, and, according to

Bhadra (

2020), it is associated with authority, in the sense that while the speaker has the authority in a declarative sentence in the sense that it is the speaker that possesses the knowledge behind an assertion, it is the addressee’s knowledge that is sought in the answer to a question.

Speas and Tenny (

2003) propose a system to explain syntactic structures attending to discourse participants (i.e., Speaker and Addressee) in the form of a set of syntactic projections housed in the left-most left periphery. This system is able to explain phenomena such as agreement with discourse participants instead of syntactic arguments, by means of coindexation, as seen in the case of unagreement in Spanish, shown in (35), in which the inflected verb

vamos ‘we go’ shows first-person plural agreement with the Speaker along with the plural subject

los lingüistas ‘linguists’.

The diagram in (36) shows

Tenny and Speas’ (

2004) proposed structure for an interrogative, which incorporates the Interrogative Flip:

7| (36) | ![Languages 08 00282 i006]() |

In the system proposed by

Speas and Tenny (

2003) and

Tenny and Speas (

2004), the

Seat of Knowledge, which

Tenny and Speas (

2004) situate within the

Utterance Content, is an evidential argument that stands for ‘the sentient individual who is responsible for the truth of a proposition’ (

Tenny and Speas 2004). In the case of interrogatives, both the Utterance Content and Seat of Knowledge are controlled by the raised Addressee. This explains why the Addressee is the discourse participant that possesses the knowledge to provide the answer to the question. For example, the Seat of Knowledge is named by evidential verbs like

appear. Because of the Interrogative flip,

appear will be anchored to the Speaker in a declarative, but to the Addressee in an interrogative, as seen in (37):

| (37) | a. | Martin appearsS to have missed his exam. (The speaker knows) |

| | b. | Does Martin appearA to have missed his exam? (The addressee knows) |

Inferential interrogatives with

qué do not seem to pattern with prototypical interrogatives with evidentials in that they do not appear to present the Interrogative Flip, at least apparently, since the inference takes the Speaker’s perspective rather than the Addressee’s. For example, in a sentence such as (38), it is the Speaker that makes an inference about the Addressee’s prior location:

8| (38) | ¿Qué | vienes, | de | la | piscina? |

| | INTER come:2SG, from | the | swimming.pool |

| | ‘Are you coming from the swimming pool (I infer)?, |

| | lit. What are you coming, from the swimming pool?’ |

Inferential evidentials in Bangla (

Bhadra 2017,

2018,

2020) also seem to lack the Interrogative Flip, as the Speaker perspective is maintained in the inference, as seen in (39):

| (39) | Mina amerika cho-e | ja-cche | naki? |

| | Mina America go-IMPERF go-3P.PRES.PROG NAKI |

| | ‘(Given what I inferred) Mina is going away to America (is it true)?’ |

| | (Bhadra 2018) |

Both in Bangla and Spanish inferential interrogatives, the Addressee still has the information that will make the requested confirmation possible. This suggests that the Addressee does have a prominent role in the Speech Act projection, as a consequence of the Interrogative Flip. For this reason, the activation of the Interrogative Flip in inferential interrogatives with qué in Spanish is assumed in our proposal.

4.2. Evidential Projections

Four types of evidentials have been identified grammatically (

Speas 2004). Different authors have proposed a compositional interpretation derived either from the different coindexations between participants and speech acts (

Speas and Tenny 2003) or by means of four different projections (

Cinque 1999;

Speas 2004).

Cinque (

1999) proposes the hierarchy shown in (40) based both on the position evidential morphemes tend to exhibit within a word and adverb placement in a sentence.

| (40) | Cinque’s (1999) hierarchy |

| | Speech Act Mood > Evaluative Mood > Evidential Mood > Epistemological Mode |

The Speech Act projection determines the type of Speech Act (e.g., interrogative), whereas the Evidential projection determines the source of the speaker’s evidence of the truth of a proposition. Evaluative mood signals an evaluation made by the speaker and epistemological mode ascertains the degree in which a speaker is certain about a proposition (

Cinque 1999;

Speas 2004). In the case of morphemes, Cinque notes that speech act or speaker evaluation morphemes tend to appear further from the verb root than other morphemes, as shown in (41).

| (41) | Malagasi | | |

| | matetika > efa > mbola > V (O) > tsara > tanteraka > foana > intsony > ve |

| | generally already still | well | completely always anymore speech act |

| | (Cinque 1999, p. 43 [207]) |

As for adverbs, he argues that adverbs such as

honestly and

frankly are associated with the Speech Act projection, adverbs such as

luckily are associated with the Evaluative projection, and adverbs such as

obviously are associated with the Evidential projection. This has an impact on the linear order that these adverbs present in a clause, as seen in (42–44), whereby evidential adverbs follow both speech act and evaluative adverbs, but precede epistemological adverbs.

| (42) | Speech act adverb honestly preceding evaluative adverb unfortunately |

| | a. | Honestly I am unfortunately unable to help you. |

| | b. | *Unfortunately I am honestly unable to help you. |

| | | |

| (43) | Evaluative adverb fortunately preceding evidential adverb evidently |

| | a. | Fortunately, he had evidently had his own opinion of the matter. |

| | b. | *Evidently he had fortunately had his own opinion of the matter. |

| | | |

| (44) | Evidential adverb clearly preceding epistemic adverb probably |

| | a. | Clearly John probably will quickly learn French perfectly. |

| | b. | *Probably John clearly will quickly learn French perfectly. |

| | | (Cinque 1999, p. 33) |

Although Spanish word order restrictions generally differ from English, Spanish adverbs also appear to respond to Cinque’s hierarchy in unmarked word order, at least regarding speech act adverbs and evidential adverbs as compared to other adverbs, as seen in (45–47).

| (45) | Speech act adverb sinceramente ‘sincerely’ preceding evaluative adverbial por suerte ‘fortunately’ |

| | a. | Sinceramente, por suerte | no | puedo | ir. |

| | | sincerely | fortunately NEG can:1SG go |

| | | ‘I sincerely can’t fortunately make it’ |

| | b. | ??Por suerte, sinceramente no puedo ir. |

| | | | | | | |

| (46) | Speech act adverb sinceramente ‘sincerely’ preceding evidential adverb claramente ‘clearly’ |

| | a. | Sinceramente, claramente | ya no | está | entusiasmado. |

| | | sincerely | clearly | no.longer | be:3SG enthusiastic:MASC |

| | | ‘Sincerely, he’s clearly no longer enthusiastic.’ |

| | b. | *Claramente, sinceramente ya no está entusiasmado. |

| | | | | | | |

| (47) | Evidential adverb claramente ‘clearly’ preceding epistemic adverb probablemente ‘probably’ |

| | a. | Claramente, este chico probablemente no | aprobará | el examen. |

| | | clearly | this boy | probably | NEG | pass:FUT.3SG | the exam |

| | | ‘Clearly, this boy won’t probably pass his exam.’ |

| | b. | *Probablemente este chico claramente no aprobará el examen. |

| | | | | | | | |

Different types of adverbs are oriented to different discourse participants in inferential interrogatives with qué. The Addressee, associated with the Speech Act, controls the Utterance Content and high adverbs such as francamente ‘frankly,’ honestamente ‘honestly,’ and sinceramente ‘sincerely.’ The Speaker, in turn, appears to be associated with the clausal level, controlling the reference of evidential adverbs such as obviamente ‘obviously,’ claramente ‘clearly,’ and evidentemente ‘evidently.’

In the sentence in (48), the adverb

honestamente ‘honestly’ obligatorily appears as a high adverb, and it is associated with the Addressee in the interrogative; that is, it is the Addressee’s honesty that is being requested. In the case of the evidential adverb

evidentemente ‘evidently’ in (49), it is lower and controlled by the Speaker; that is, it is the Speaker that makes the inference rather than the Addressee, even if the sentence is interrogative.

| (48) | Speech Act adverbs are addressee-oriented |

| | ¿Honestamentei | qué | vienesi, | de | la | fiesta? |

| | Honestly | what | come:2SG | from | the | party |

| | ‘Honestly, are you coming from the party, |

| | lit. honestly, what are you, coming from the party?’ |

| (49) | Evidential adverbials are speaker-oriented |

| | ¿Qué vienesi | evidentemente*i, | del | supermercado? |

| | what come:2SG evidently | from.the | supermarket |

| | ‘Are you evidently coming from the supermarket, |

| | lit. what are you evidently coming, from the supermarket?’ |

The contrast in the anchoring of the different adverbs with different clause participants in (48–49) is evidence of the activation of the interrogative flip in Spanish evidential interrogatives with qué, demonstrating the Addressee’s raising to a higher position where it controls high adverbs. It also proves the existence of a clausal layer controlled by the Speaker. We explain how the Speaker’s point of view becomes active in these constructions next.

4.3. The Clause Logophoric Component: Point of View

Speas (

2004) and

Bianchi (

2003,

2006) propose the existence of logophoric pronouns in a clause, representing the discourse participants’ point of view. According to

Bianchi (

2003), every finite clause is anchored to the time of utterance or speech event (S), whereas non-finite clauses need to be anchored to the main clause. The speech time (S) is located in Fin, in the left periphery, as shown in (50).

| (50) | [Force [(topic*) [(Focus) [Fin [… Tense VP]]] |

| | (Bianchi 2003) |

Bianchi further proposes that only a finite construction encoding S may license person agreement, as it corresponds to a speech event, identified by Bianchi as the center of deixis, which includes the discourse participants as well as spatial and temporal coordinates determining finiteness.

Sells (

1987) distinguishes three distinct logophoric roles, which are relevant here, as they differentiate between different sources of information being reported: the source is the individual doing the reporting, the self is the individual whose mind is reported, and the physical point of view from which the report is made is the pivot.

Bianchi formally identifies the speech event as a Logophoric Center. Each Logophoric Center obligatorily projects an animate participant (i.e., the Speaker or Source), a typically optional Addressee in speech events, although the Addressee may be obligatory depending on the nature of the speech event (e.g., commands, questions). The Logophoric Center also contains temporal and spatial coordinates. This system is interesting because these logophoric pronouns can be coindexed, either with clausal arguments or with discursive participants, which affects phenomena such as agreement with discursive participants. For example, it would explain the agreement of the verbal features with the speaker together with a clausal argument in interrogative sentences such as (51), typical between a medical doctor and a patient (

Jiménez-Fernández and Tubino-Blanco 2022).

| (51) | ¿Cómo estamos | hoy? |

| | how | be:1PL | today |

| | ‘How are we today?’ |

The presence of the Logophoric Center controlling a Speech Act projection would also account for restrictions associated with the inclusive or exclusive interpretation of first-person plural pronouns and their interplay with information structure in Spanish. This fact was shown, for example, in

Jiménez-Fernández and Tubino-Blanco (

2022). Their system explains the restriction to use an overt first-person plural pronoun in an out-of-the-blue context, as seen in (52).

Blain and Déchaine (

2007) argue that operators may enter a clause at different levels (ie., vP, AspP, AgreeP, CP), leading to different semantic consequences. At the CP level, evidentials affect the Speech Act; at the vP level, they introduce the Speaker’s perspective in the predicate. In

Speas’ (

2004) system, a logophoric pronoun may not be the same as the prominent participant in the matrix Speech Act. For example, in (53) the Speaker would be Evaluator but someone different would be Witness and Perceptor:

| (53) | [proi SAP [proi EvalP [ proj EvidP [proj EpisP]]]] |

In Bangla (

Mukherjee 2008;

Bhadra 2017,

2018,

2020), the evidential morpheme

naki changes its evidential contribution depending on the Speech Act in which it appears. If the morpheme appears in a declarative sentence and middle position, the morpheme has a reportative interpretation, but if it appears in an interrogative sentence and final position, it has an inferential interpretation. In this sense, it is similar to inferential interrogatives with

qué. In fact,

Mukherjee (

2008) proposes that in the case of interrogatives,

naki is a confirmation particle, an interpretation that has been previously proposed also for the tag portion in Spanish inferential interrogatives (

López-Cortina 2003,

2009). Bhadra nonetheless proposes that, in both cases,

naki is an indirect evidential and its interpretation is compositional. We see examples in (54):

| (54) | Mukherjee (2008) |

| | a. | Shila naki | gaan | Sikh-ch-e |

| | | Shila INFER song | learn-PROG-3 |

| | | ‘Shila is learning music, as I have heard’ |

| | b. | Sita baRi | giy-ech-e | naki? |

| | | Sita home | go-PERF-3 | CONFIR |

| | | ‘(From what I infer) Sita has gone home. Has she?’ |

Bhadra (

2018) proposes two additional coordinates with respect to the ones proposed by Bianchi, which correspond with the discourse participants. These are different from the participants in Speas and Tenny’s Speech Act projection. Bhadra proposes that either within or below the SaP projection we can find a FinP projection that accounts for the finite clause’s point of view, which may correspond or not to the reference of discourse participants. This projection can be integrated either within SaP or below.

| (55) | ![Languages 08 00282 i007]() |

Keeping all these pieces in mind, we proceed to our analysis, which is spelled out in the next section.

5. A Formal Proposal for Inferential Interrogatives with qué

Our proposal is based on the following premises:

- (i)

The Addressee is located in a higher position within the Speech Act Phrase, which also explains the interpretation of the construction as an interrogative Speech Act (

Miyagawa 2022). In this sense, it is the Addressee who controls the Utterance Content and Seat of Knowledge positions (

Speas and Tenny 2003).

- (ii)

The Speaker maintains its coindexation with the evidential material by means of coindexation with FinP logophoric projection, where the confirmation proposition is located (

Bhadra 2018).

This explains why these sentences appear to be hybrid, in the sense that they appear to exhibit both partial and total interrogative behavior. It also explains why both Speaker and Addressee perspectives are present in the clause.

Evidence in favor of this hybrid structure is that the speech act adverb

honestamente ‘honestly’ in (48) is anchored to the addressee, whereas the evidential adverb

evidentemente ‘evidently’ is anchored to the speaker in (49). This leads us to propose two contrasted levels in the internal composition of these sentences, The Utterance level above is configured as an interrogative Speech Act, where the Addressee is the prominent role as a consequence of the Interrogative Flip, and where Speech Act adverbs are licensed. Below this level the clausal level can be found, where evidential adverbs are licensed and controlled by the Speaker, which represents this level’s point of view (see

Kim 2012 for a similar view and further argumentation on the anchoring of different types of adverbs by distinct discourse roles).

This configuration results in evidential interrogatives with

qué, where we simultaneously find evidential material that houses the Speaker’s point of view and classic interrogative material with the Addressee as the Seat of Knowledge, manifesting as the request for confirmation of the interrogative’s truth value. To account for this configuration, we propose the construction in (56b) based on the sentence in (56a):

| (56) | a. | ¿Qué | vienen | ustedes, | en tren? |

| | | what | come:2PL | 2PL | on train |

| | | ‘Do you all come by train (I infer) |

| | | lit. what do you all come, by train?’ |

| | | |

| | b. | ![Languages 08 00282 i008]() |

In the configuration in (56), the interrogative operator and the inferred material are base-generated in a Small Clause (SC) in

vP. This accounts for the connection between the operator and the tag, given that the operator is clearly requesting information about the content of the tag. The inferential material remains in a lower position, which is typical of foci in Spanish. Both the evidential and discursive component of the structure take place at the CP layer, where the point of view and speech act relations take place. These evidential interrogatives are characterized by the fact that the evidential material is oriented to the Speaker rather than the Addressee. This is possible since it is the Speaker that occupies the [Spec, FinP] position, hence controlling the point of view of the material within the clause, including the tag (i.e., the SC). At the Speech act level, the interrogative character of the construction has additional consequences. The SC has a focus feature, which results in the movement of the operator

qué to the [Spec, ForceP] position, passing through [Spec, FocP], since this ForceP projection has an Edge Feature (i.e., EPP in interrogatives). The reason why the SC has a focus feature is because one of its members (the tag) will end up being interpreted as the focus. The verb in turn moves to T and then to the ForceP head. At the discursive level, the Addressee takes a prominent place to reflect the interrogative character of the construction, moving from its neutral position in the complement of SaP to a [Spec, SaP] position, controlling the Seat of Knowledge, typical of interrogatives, which will be interpreted in the form of an information-seeking utterance.

9This analysis reflects configurationally the structure of this marked interrogative type, in which the information sought by the Speaker is interpreted as a confirmation, as a consequence of the presence of evidential material controlled by the Speaker. Next, we discuss further structural and prosodic consequences resulting from this construction.

6. Some Consequences

In this section, we discuss both structural and prosodic consequences derived from the configuration proposed in (56).

6.1. Some Structural Consequences

In the proposed analysis in (56), we propose, contra

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020a,

2020b), that both the operator and the verb move to Force. This would explain that when the subject is explicit, it is pronounced before the inference:

| (57) | ¿Qué vienen | ustedes, | en tren? |

| | what come:2PL | 2PL | by train |

| | ‘Do you all come by train (I infer)? |

| | lit. what do you all come, by train?’ |

Also, embedding of the inferential interrogative appears to be possible, as seen in (22), here repeated as (58), which suggests that the operator undergoes long-distance movement to the matrix CP:

| (58) | Long-distance movement |

| | a. | ¿Qué te | fastidia | que venga, | el | sábado? |

| | | what CL:2SG | annoy:3SG | that come:1SG, | the | Saturday |

| | | ‘Do you regret that I’m visiting on Saturday (I infer)?’ |

| | b. | ¿Qué no | te | viene bien | que venga, | el | sábado? |

| | | what NEG | CL:2SG | come well | that come:1SG, | the | Saturday |

| | | ‘Isn’t it good for you that I’m coming Saturday (I infer)?’ |

In dialects without an Edge Feature in ForceP, both the operator

qué and the inferential material would stay in situ, as in (59), which reflects the original position where the interrogative pronoun is generated:

Evidence that the tag is integrated within the clause rather than a second interrogative is the fact that the same temporal adverbial, associated with the matrix tense, may appear both with the tag or outside, as shown in (60). Note that the comma placement reflects the prosodic contour:

| (60) | a. | ¿Qué vas | mañana, | al | hospital? |

| | | what go:2SG tomorrow, to.the hospital |

| | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿Qué vas, al hospital mañana? |

| | | ‘Are you going to the hospital tomorrow (I infer)’ |

Further evidence in favor of the monoclausality of these sentences is the fact that the material in the tag can never be a finite clause, in contrast with other types of split interrogatives, as seen in (61):

| (61) | a. | * ¿Qué | va, | va | los fines de semana? |

| | | what | go:3SG | go:3SG | the weekends |

| | | Intended: Does he go on weekends (I infer)?’ |

| | | | | | | |

| | b. | ¿Cuándo va, | va | los fines de semana? |

| | | when go:3SG | go:3SG | the weekends |

| | | ‘Does he go on weekends?’ |

Related to this point,

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020b) argue that if these constructions were the result of ellipsis in the second clause, as a biclausal analysis of the construction would posit, sentences such as (62) would be grammatical, contrary to fact:

Miyagawa and Hill (

2023) argue that English interrogatives with evidential content may be compatible with

after all despite the fact that this discourse marker is associated with declaratives, as shown in

Sadock (

1974):

| (63) | a. | After all, your advisor is out of the country. |

| | b. | #After all, is your advisor out of the country? |

| | | | |

| (64) | Evidential interrogative |

| | After all, is the Pope catholic? |

| | | | (Miyagawa and Hill 2023: [22, 25]) |

In spite of the interrogative nature of the inferential constructions studied here, they combine with the discourse marker

después de todo ‘after all’, proof that these structures include evidential material at the syntactic level:

| (65) | Después | de todo | ¿qué vienes, | con las | manos vacías? |

| | after | of all | what come:2SG | with the:FEM.PL | hand:PL empty:FEM.PL |

| | ‘Do you come with empty hands after all (I infer)?’ |

Next, we discuss some prosodic consequences derived from the construction.

6.2. Prosodic Consequences

The analysis in (56) is in line with

Escandell-Vidal’s (

2017) proposal according to which the evidential feature appears in interrogatives as a consequence of compositionality, resulting from the conjunction of point of view features and interrogative features. Escandell-Vidal distinguishes three contours associated with interrogatives: the canonical low-rise pattern (66) and two marked patterns, high-rise (67) and rise-fall (68).

| (66) | Low-rise yes/no question (canonical interrogative contour) |

| | ¿Has | vivido | siempre aquí? |

| | have:2SG | lived | always here |

| | ‘Have you always lived here?’ |

| (67) | High-rise (marked interrogative contour) |

| | Cuando empezó | la televisión | en los | años sesenta y | tal | pues me |

| | when start:3SG.PERF | the TV | in the:PL | years sixty and | such | well CL:1SG |

| | parece | muy bien que | tenga | que | haber televisión, | española |

| | | | | | | |

| | seem:3SG very well that | have:3SG.SUBJ that | there.be TV | Spanish |

| | pero | ¿ahora? // | es que no | le | veo | ningún | sentido |

| | | | | | | | |

| | but | now | be that NEG | CL:3SG | see:1SG | no | sense |

| | | | | | | | |

| | ‘When television began in the sixties, it made sense to have a Spanish television, |

| | but nowadays? I can’t see the point of it!’ |

| (68) | Rise-fall (marked interrogative contour) |

| | A: | ¿Y | si fueses | presidente de…? |

| | | And if be:2SG.IMPERF.SUBJ | president of |

| | | ‘If you were the president of…’ |

| | | | | | |

| | B: | ¿Si fuese | presidente de España? |

| | | if | be:1SG.IMPERF.SUBJ | president of Spain |

| | | ‘If I were the president of Spain?’ |

| | (Escandell-Vidal 2017: [2,5,7]) |

The sentence in (66) shows a canonical yes/no interrogative whereby the Speaker asks some specific information that the Addressee is expected to provide. In (67), the Speaker asks a question the answer to which she already knows and is ready to provide. In (68), the interrogative is an echo-question. According to Escandell-Vidal, the canonical low-rise contour is the consequence of unspecified sentence polarity corresponding to the wh-operator, but the marked contours indicate the presence of evidential material in the sentence, indicating the information source. In her proposal, in the case of high-rise contours, the source of information would be the Self, that is, the evidential would be controlled by the Speaker. In the case of rise-fall contours, the information source would be the Other, that is, the evidential is addressee-oriented, according to Escandell-Vidal.

Although Escandell-Vidal does not discuss inferential interrogatives with qué, the marked fall-rise contour associated with these interrogatives is consistent with her proposal that marked intonation contours suggest the presence of evidential material. In this case, the source of information is hybrid, whereby the ‘Self’ (the Speaker) does the inferring, and the ‘Other’ (the Addressee) possesses the Seat of Knowledge.

For

Escandell-Vidal (

2017), the interrogative feature introduces a set of propositions {p, ~p}, where only one proposition is true, over which the evidential operates. The fall–rise contour associated with inferential interrogatives with

qué indicates that the Seat of Knowledge is the ‘Other’, with scope over the true option and marked with the fall part of the contour. The inferential evidentiality part, associated with the ‘Self’ and rising intonation, operates over a hypothesis, which is explicit in the question.

Moreover, the intonational contour associated with these constructions is further evidence that they are monoclausal rather than biclausal constructions and that the tag is fully integrated within the interrogative, forming one prosodic unit, as also argued by

Fernández-Sánchez and García-Pardo (

2020b). Proof of this is that the tag cannot be an independent sentence, as shown also by

Wiltschko and Heim (

2016) for English confirmational tags:

| (69) | a. | English confirmationals |

| | | You have a new dog. [*Eh?/*Huh?/*Right?] |

| | | | | Wiltschko and Heim (2016, p. 311[12]) |

| | | | | | | |

| | b. | Spanish inferential interrogatives with qué |

| | | *¿Qué | vienes? | ¿De | la | calle? |

| | | what | come:2SG | from | the | street |

| | | ‘Are you coming back from outside (I infer)? |

| | | lit. ¿what are you coming? ¿from the street?’ |