2.1. Pseudopartitivity and Nominal Status

Pseudopartitive constructions (5) are made up of two parts linked by the functional preposition

de: (a) the head, which includes a quantifier or quantifying expression; (b) the tail, which contains an unbounded bare plural or uncountable noun phrase related to the quantification in (a). Semantically speaking, they introduce one single set, corresponding to the bare nominal, the head denoting a measure or quantity of the N in the tail (for a more detailed description of pseudopartitives see

Brucart 1997;

Di Tullio and Kornfeld 2012;

Mare 2016;

RAE-ASALE 2009; among others).

| (5) | a. | [Un grupo]HEAD de [estudiantes]TAIL |

| | | ‘A group of students’ |

| | b. | [Un poco]HEAD de [cerveza]TAIL |

| | | ‘A bit of beer’ |

| | c. | *[Un grupo]HEAD de [los estudiantes]TAIL |

| | | ‘A group of the students’ |

| | d. | *[Un poco]HEAD de [persona]TAIL |

| | | ‘A bit of person’ |

As clearly shown in (6) below,

«La de…» behaves like a pseudopartitive in that the inclusion of non-bare plural or singular count nouns gives rise to ungrammatical sentences. This means that the noun in the tail must necessarily be unbounded.

| (6) | a. | ¡[La]HEAD | de | [estudiantes]TAIL | que | vino a la fiesta! | |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | students | that | came to the party | |

| | | ‘How many students came to the party!’ |

| | b. | ¡[La]HEAD | de | [cerveza] TAIL | que | tomamos | anoche! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | beer | that | drank | last night |

| | | ‘How much beer we drank last night! |

| | c. | *¡[La]HEAD | de | [los estudiantes]TAIL | que | vino a la fiesta! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | the.Pl.Masc students | that | came to the party |

| | | ‘*How many the students came to the party!’ |

| | d. | *¡[La]HEAD | de | [persona]TAIL | que | vino a la fiesta! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | person | that | came to the party |

| | | ‘*How many person came to the party!’ |

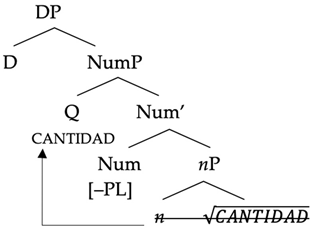

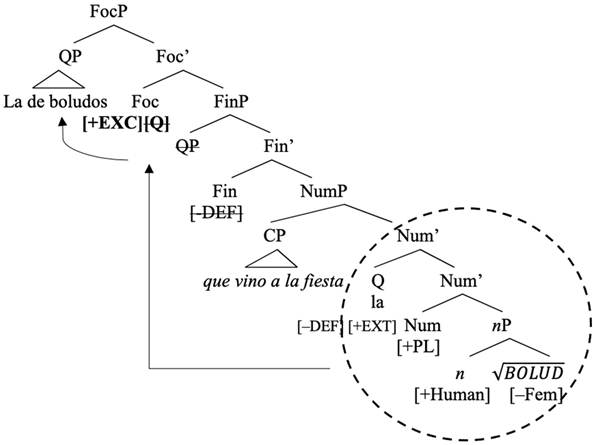

Notice, however, that there seem to be two apparent differences between (5) and (6). The first one has to do with the fact that the head of the data in (6) does not appear to contain a quantifier noun, as is the case in (5) with the Ns

grupo or

poco. This is because the pattern under study emerged from the elision of the feminine noun

cantidad (‘quantity’) (

Bosque 2017;

Brucart 1999;

Fernández Ramírez 1951;

RAE-ASALE 2009;

Roca 2009;

Torrego 1988; etc.), which eventually resulted in the grammaticalization of the article and its subsequent reanalysis as a weak evaluative quantifier tantamount to

mucho (‘much/many’), given that the reading it yields suggests excess of quantification from the perspective of the speaker (7) (see

Section 4). Contrary to other nominal exclamatives (8), the pattern rejects qualitative interpretations; that is, a sentence such as (7b) could never be paraphrased as

¡Qué cosas tan raras por las que se preocupa Mario! (‘How strange the things that Mario worry about!’).

| (7) | a. | ¡La (cantidad) de cerveza que tomaste en la fiesta! |

| | | =Tomaste mucha cerveza en la fiesta. |

| | | ‘You drank too much beer at the party!’ |

| | b. | ¡La (cantidad) de cosas por las que se preocupa Mario! |

| | | =Mario se preocupa por muchas cosas. |

| | | ‘Mario worries about too many things!’ |

| (8) | ¡Las cosas por las que se preocupa Mario! |

| | Quantitative reading: ‘Mario worries about too many things!’ |

| | Qualitative reading: ‘How strange the things that Mario worry about!’ |

The second difference between (5) and (6) concerns the definiteness of the structures. A distinguishing feature of pseudopartitives is that they host indefinite nouns or quantifiers (e.g.,

un centenar de libros, un poco de pan, un grupo de manifestantes, etc.). In spite of the fact that the head of the examples in (6) is the definite article

la, the reading we obtain is evidently existential and indefinite, as proven by the paraphrases with quantifiers like

mucho (‘too much/many’) in (7) and by the following sentences, in which definiteness effects are not available when combined with the existential verb

haber to express a locative meaning:

1| (9) | a. | ¡La de estudiantes que hay en la nueva universidad! |

| | | Hay muchos estudiantes en la nueva universidad. |

| | | ‘There are many students in the new university’ |

| | b. | ¡La de libros que hay sobre el escritorio! |

| | | Hay muchos libros sobre el escritorio. |

| | | ‘There are many books on the desk’ |

As is the case with the pseudopartitive constructions in (10), the data analyzed in this paper give rise to alternating agreement patterns, as the verb in the relative clause might agree with the head of the structure or with the unbounded noun in the tail, in which case there would be

ad sensum agreement or

silepsis.

| (10) | a. | Un | grupo de alumnos | trabaja/trabajan | en este bar |

| | | A | group of students | works/work | in this bar |

| | | ‘A group of students works/work in this bar’ |

| | b. | Un | montón de personas | visitó/visitaron | las Cataratas del | Iguazú |

| | | A | lot of people | visited.3.Sg/visited.3.Pl | the Falls of the | Iguazu |

| | | ‘A lot of people visited the Iguazu Falls’ |

| (11) | a. | ¡La | de | alumnos | que | trabaja/trabajan | en este bar! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | students | that | works/work | in this bar |

| | b. | ¡La | de | personas | que | visitó/visitaron | las Cataratas del Iguazú! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | people | that | visited.3.Sg/visited.3.Pl | the falls of-the Iguazu |

Lastly, the examples in (12) and (13) indicate, on the one hand, that

«La de...» forms a constituent that can be coordinated and, on the other, that when it comes to agreement, the N in the tail is the element with which the predicative adjectives after a copula agree.

| (12) | ¡Madre mía, la de gilipollas y la de gilipolleces que tengo que aguantar! |

| | ‘Oh, my god, how many stupid people and things I have to tolerate!’ |

| (13) | a. | ¡La | de | alumnos/as | que | están desempleados/as! | |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | students.Masc.Pl/Fem.Pl | that | are unemployed.Masc.Pl/Fem.Pl |

| | b. | *¡La | de | alumnos/alumnas | que | está desempleada! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | students.Masc.Pl/Fem.Pl | that | are unemployed.Fem.Sg |

Crucially, the ungrammaticality of (13b) appears to point to the lack of referentiality of

la, which is in accordance with the hypothesis we will further advance in

Section 4 that it is a quantifier. In fact, as an anonymous reviewer observes, (13b) contrasts sharply with the grammaticality of the pseudopartitive in (14), where

cantidad seems to be a full N, with referential properties, equivalent to

cifra ‘figure.’

| (14) | ¡La cantidad de alumnos que se han inscripto en media hora! |

| | ‘The number of students that have enrolled in half an hour!’ |

2.2. Exclamation and Clausal Status

One of the key ingredients that characterizes the pattern

«La de...» is its exclamative import. Exclamatives are expressive speech acts that manifest an emotional reaction on the part of the speaker, such as surprise, disbelief or elation. In

Zanuttini and Portner’s (

2003) terms, a sentence as that in (15) implies that the extent or degree to which the mass noun

cerveza is predicated exceeds or outranks the range of expected possibilities, which is the reason why, according to the authors, there is a

widening effect. The pseudopartitive construction then introduces a variable whose domain includes a set of non-standard propositions, i.e., of all the possible values that the variable X could obtain, the DP belongs to the subset of the least expected ones, to that which can be located in the extremes of implicit pragmatic scales of standardness, expectation or plausibility.

| (15) | ¡La de cerveza que tomaste en la fiesta! |

| | ‘How much beer you drank at the party!’ |

The widening of the quantificational domain is closely intertwined with the fact that exclamative sentences generate conventional scalar implicatures in observance with their impossibility of occurring in interrogative or negative sentences (

Portner and Zanuttini 2005). This is attributable to the concomitance of exclamation and factivity, as the speaker presupposes the truth of the proposition which the exclamative utterance encodes.

| (16) | a. | ¡Es increíble la de cerveza que tomaste en la fiesta! |

| | | ‘It’s incredible how much beer you drank at the party!’ |

| | b. | *¡No es increíble la de cerveza que tomaste en la fiesta! |

| | | ‘*It’s not incredible how much beer you drank at the party!’ |

| | c. | *¿¡Es increíble la de cerveza que tomaste en la fiesta!? |

| | | ‘*Is it incredible how much beer you drank at the party!?’ |

According to

Bosque’s (

2017) classification of exclamative constructions, the structures under consideration fall within the group of

primary exclamatives, given that there is an explicit syntactic or lexical clue that signals its illocutionary force. Said clue is the article

la, which, as will be discussed in the next section, behaves like an exclamative operator equivalent to

cuántos. Furthermore, our data can be considered

definite article degree exclamatives, sometimes also called

degree relatives or

exclamatives with emphatic articles, such as those illustrated below in (17).

2 In both cases, definite articles are used for emphasis.

| (17) | a. | ¡Los (incontables) sitios que ha visitado este hombre! |

| | | ‘The (innumerable) places that this man has visited!’ |

| | b. | ¡Lo (muy) inteligente que es María! |

| | | ‘How very clever Maria is!’ |

| | c. | ¡Lo (increíblemente) rápido que va este coche! |

| | | ‘How (incredibly) fast this car runs!’ |

| | | Bosque (2017, p. 22) |

The application of other typical diagnostics in the literature (

Bosque 2017;

Masullo 2017; etc.) that enable us to tell exclamatives apart is also possible when it comes to

«La de…» structures. In addition to sharing the semantic, pragmatic and prosodic properties of other prototypical exclamative constructions, the pattern with the feminine article under study: (i) can be embedded as the complement of verbs such as

ver, mirar, fijarse and non-factive volitive verbs such as

encantar/sorprenderse (18); (ii) cannot cooccur with other elements which, according to the standard treatment in the bibliography, occupy the same syntactic position (i.e., specifier of FocP or CP) (19); (iii) cannot be used in sentences whose illocutionary force is jussive, dubitative or desiderative (20);

3 (iv) admits a resultative or consecutive sequel or coda (21); (v) can function as the argument of predicates such as

increíble, both as subjects and as the adjacent adjectival complement (22).

4| (18) | Prototypical exclamatives: |

| | a. | ¡Mirá cuánta gente que vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘Look how many people came to the party!’ |

| | b. | *¡Me temo cuánta gente que vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘*I’m afraid how many people came to the party!’ |

| | «La de…» exclamatives: |

| | c. | ¡Mirá la de gente que vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘Look how many people came to the party! |

| | d. | *¡Me temo la de gente que vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘*I’m afraid how many people came to the party!’ |

| (19) | Prototypical exclamatives: |

| | a. | *¿¡Qué vino cuánta gente que compró!? |

| | | ‘*What a wine how many people bought!?’ |

| | «La de…» exclamatives: |

| | b. | *¿Qué chicos la de gente que vieron en el parque!? |

| | | ‘*What boys how many people saw in the park!?’ |

| (20) | Prototypical exclamatives: |

| | a. | *¡Tal vez cuánta gente que vino! |

| | | ‘*Maybe how many people came!’ |

| | «La de…» exclamatives: |

| | b. | *¡Tal vez la de gente que vino! |

| | | ‘*Maybe how many people came!’ |

| (21) | Prototypical exclamatives: |

| | a. | ¡Qué caro que está todo que somos los únicos que tienen auto! |

| | | ‘How expensive everything is that we are the only ones with a car!’ |

| | «La de…» exclamatives: |

| | b. | ¡La de gente que vino que nos quedamos sin alcohol a la medianoche! |

| | | ‘So many people came that we’ve run out of alcohol at midnight!’ |

| (22) | Prototypical exclamatives: |

| | a. | ¡Es increíble cuánta gente vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘It’s incredible how many people came to the party!’ |

| | «La de…» exclamatives: |

| | b. | ¡Es increíble la de gente que vino a la fiesta! |

| | | ‘It’s incredible that so many people came to the party!’ |

| | c. | ¡La de gente que vino a la fiesta es increíble! |

| | | ‘That so many people came to the party is incredible!’ |

The empirical evidence offered above bears out the hypothesis that the structures introduced by

«La de…» are analogous to true

wh- exclamatives. They do not constitute ‘covert’ (

Masullo 2017) or ‘total’ or ‘secondary’ exclamative clauses (i.e., structures whose intonation and proper interpretation of the exclamative illocutionary force associated with it are the linguistic markers of exclamative import (

Bosque 2017, p. 7)) but rather structures whose semantic, syntactic, pragmatic and prosodic features coincide with the so-called genuine or partial exclamatives, i.e., those which contain an overt exclamative operator.

2.3. A ‘Relative’ Relative Clause

In the previous subsection, we highlighted the resemblance between

«La de…» and other types of partial exclamatives. A dissimilarity which was not mentioned, however, is that in the

«La de…» pattern the presence of

que (‘that’) is mandatory (23), while in (24) it is optional. In our view, this discrepancy stems from the hybrid and chimeric status of the construction, because, even though it displays all the characteristics of exclamative clauses, its syntactic structure is that of a DP.

| (23) | ¡La | de vino *(que) | tomamos | anoche! |

| | Art.Fem.Sg | of wine that | drank | last night |

| | ‘How much wine *(that) we drank last night! |

| (24) | ¡Cuánto | vino | (que) | tomamos | anoche! |

| | How-much | wine | that | drank | last night |

| | ‘How much wine (that) we drank last night! |

Some authors such as

Bosque (

2017),

Brucart (

1999),

RAE-ASALE (

2009) or

Masullo (

2012) contend that the underlying configuration of definite article degree exclamatives corresponds to a clause. From this perspective,

la de vino would be the direct object of the verb

tomamos, and would be displaced to the initial position by means of a process of prolepsis or operator movement. Accordingly, the word

que (‘that’) would be a complementizer or subordinating conjunction, as the form

que in (24) is generally analyzed (see

Brucart 1999;

Plann 1984, etc.). In this paper, and along the lines of

Torrego’s (

1988) and

Portner and Zanuttini’s (

2005) proposals, we will defend the divergent view that the string is a DP that contains a subordinate relative clause, which is most of the times introduced by the relativizer

que, although other relativizers are possible. We will now proceed to outline the arguments in favor of this analysis.

First and foremost, the strongest piece of evidence to support our hypothesis is that it is possible to find examples in which the pseudopartitive construction is followed by a clause headed by other simple relativizers—e.g.,

cuyo (‘whose’) and

donde (‘where’) (25a–b)—or else by complex relativizers with prepositions, as in (25c–d).

5 Note the correspondence with the sentences in (26), which include canonical relative clauses.

| (25) | a. | La de gente cuya vida no vale nada |

| | | ‘How many people whose life is worthless!’ |

| | b. | ¡Increíble la de lugares donde aún se permite fumar en el interior de los bares! |

| | | ‘It’s incredible the number of places where it’s allowed to smoke indoors!’ |

| | c. | ¡La de chongos con los que chateé anoche en Scruff! |

| | | ‘The guys with whom I chatted yesterday on Scruff!’ |

| | d. | ¡¡La de sitios en los que has estado en estos 30 años de profesión!! |

| | | ‘The places in which I’ve been in my 30-year career!’ |

| (26) | a. | Me entristece la gente cuya vida no vale nada |

| | | ‘I’m sad about people whose life is worthless.’ |

| | b. | Han multado los lugares donde aún se permite fumar en el interior de los bares. |

| | | ‘They have fined the place where it’s allowed to smoke indoors.’ |

| | c. | Los chongos con los que chateé anoche en Scruff me bloquearon. |

| | | ‘The guys with whom I chatted yesterday on Scruff blocked me.’ |

| | d. | Le mostré los sitios en los que he estado en estos 30 años de profesión. |

| | | ‘I showed them the places in which I’ve been in my 30-year career’ |

Additional evidence comes from case-assignment phenomena. In some Romance languages, relative clauses have been shown to display some of the possibilities of case assignment found in long- and short-distance syntactic dependencies, be it upward or downward case attraction. Consider the following paradigm taken from

Agulló (

2023).

| (27) | a. | Hay en sitios que se hace una morcilla un poco más dulce (COSER, Etxauri, Navarra) |

| | | ‘There are places in which a sweeter blood sausage is made’ |

| | b. | Hay a gente que la echan por cualquier tontería (CORPES XXI, PRESEGAL, Spain). |

| | | ‘There are people who are fired for nothing’ |

| | c. | Hay a personas que hay que reñirlas más (COSER, Cigales, Valladolid). |

| | | ‘There are people that should be told off more frequently’ |

In the examples in (27), the underlined prepositions appear after the existential verb

haber in an unexpected position, different from the one in which they originate. The locative preposition

en (27a), the differential object marker (27b) and the dative preposition

a (27c) belong to the CP introduced by

que but are spelled out as though they were case marking the pivot of the existential clauses, which, in Spanish, are known to reject DOM, e.g.,

Hay (*a) muchos edificios nuevos en Buenos Aires; ‘There are many new buildings in Buenos Aires.’ These data can lend support to the claim that the sequence headed by

que in the structures under study is a relative clause, as upward case attraction can also be found.

6| (28) | a. | ¡La de gente a la que has visto! |

| | b. | ¡A la de gente que has visto! |

| | c. | ¡A la de gente a la que has visto! |

| | d. | ¡La de gente que has visto! |

| | | ‘How many people you’ve seen!’ |

In (28a), the DOM preposition of the verb

visto appears in its default position within the relative clause, pied-pied by the complex relative

la que. In (28b) and (28c), it seems to be case marking the whole DP, occupying the upmost position, although in the latter a copy of the preposition remains in the default position. While a clausal analysis might account for the position of the preposition in (28b), by proposing that

a la de gente is the DO of

visto and is displaced to the left periphery of the clause, it fails to explain why it might occur before the apparent complementizer and not before the DO in (28b), or in both positions (in Spec-CP and Cº) (28c) or, fundamentally, why it most frequently does not appear altogether, as in (28d). The non-occurrence of the DOM preposition typically found with verbs like

ver ‘see’ (29a) follows from the fact that the relativizer

que does not need to be case marked (29b), as opposed to complex relativizers (29b), which indeed do. This paradigm can elegantly explain the behavior of

a in (28), while a clausal analysis, to the best of our knowledge, would encounter several difficulties in doing so.

| (29) | a. | Vi | | a | los chicos | en la fiesta. | Son geniales |

| | | Saw | | DOM | the guys | at the party | Are great |

| | | ‘I saw the guys at the party. They are awesome. | |

| | b. | Los chicos | (*a) | que | vi | en la fiesta | son geniales |

| | | The guys | DOM | that | saw | at the party | are great |

| | c. | Los chicos | *(a) | los que | vi | en la fiesta | son geniales |

| | | The guys | DOM | The that | saw | at the party | are great |

| | | ‘The guys I saw at the party are awesome’ | |

Examples such as (30) with reduced relative clauses—that is, with non-finite verbs—are also attested. This specific example, moreover, indicates that the pattern can be preceded by the preposition

con (‘with’), which definitely requires a nominal complement, as shown in (31).

| (30) | Te | meás | en verdad | con | la | de | gente | estudiando |

| | CL.2.Sg | pee | in truth | with | Art.Fem.Sg | of | people | studying |

| | psicología con 0 capacidad de empatía y análisis. |

| | Psychology with 0 capacity of empathy and analysis |

| | ‘You won’t believe how many people there are studying psychology without any empathy or analysis’ |

| (31) | a. | ¡Con | | | | la casa | | | | | que | tiene! | | | |

| | | With | | | | the house | | | | that | has | | | |

| | | ‘In spite of the house that he has!’ | | | | | | | | | | |

| | b. | Con | lo | que | come | ese muchacho | | | | | | | | |

| | | With | what | that | eats | that guy | | | | | | | | | |

| | | ‘Despite what that guy eats!’ | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | c. | Ya no se | puede | jugar al | fútbol | con | la | de | | | giles | | | | |

| | | Still not Cl | can | play to-the | football | with | Art.Fem.Sg | of | | | fools | | | | |

| | | que | | | hay | | acá | | | | | | | | |

| | | That | | | are | | here | | | | | | | | |

| | | ‘You can’t play football what with the fools that there are here! | | | | | | | |

| | d. | *¡Con | | cuánto | | | | | come | | ese muchacho! | | | |

| | | With | | how-much | | | | eats | | that guy | | | | |

| | | ‘*Despite how much that guy eats!’ | | | | | | | | | | |

| | e. | *¡Ya | no | | | se | | puede | | jugar | al fútbol | | con | cuántos giles |

| | | Still | not | | | CL | | can | | play | to-the football | with | wow-many fools |

| | | que | hay acá | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | that | are here | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | ‘*You can’t play football what with how many fools there are here!’ | | | | | | | |

If the clause introduced by

que is a relative clause, it follows that the omission of the relativizer be ruled out, as shown in (23). It is a well-known fact that, in Spanish, as opposed to other languages such as English, it is not possible to find contact relative clauses, i.e., those in which the relativizer is phonologically null. If, alternatively, the whole structure is clausal and

que is just a complementizer or subordinating conjunction, the reason why

que is mandatory here but optional in the rest of the exclamative clauses such as

¡Cuánto/qué calor (que) hace! (‘How hot it is!) remains unexplained. Furthermore, as is well known with relative clauses, nominal exclamatives can both be stacked and coordinated.

| (32) | ¡La de gente que conocí que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei! |

| | ‘How many people I know who study at college and vote for Milei!’ |

Notice that a clausal analysis of a sentence such as (32) cannot smoothly account for the non-movement of the stacked and coordinated

que clauses after the main predicator

conocí. Let us assume that the whole structure is indeed a CP and that the constituent

la de gente que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei allows discontinuous spell out, as is schematically represented in (33). If this were the underlying structure of (32), the non-discontinuous spell out (33b) would also be expected and other similar focalized constructions (33c) could be analyzed in a similar fashion. However, as (33b–c) show, this does not occur.

| (33) | a. | [CP [La de gente que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei]C que [TP conocí [la de gente que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei]]]. |

| | b. | ??[CP[La de gente que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei]C que[TP conocí [la de gente que estudia en la Universidad y que vota a Milei]]]]. |

| | c. | *La gente, conocí [la gente que estudia en la universidad y que vota a Milei]. |

| | ‘The people, I met who study at college and vote for Milei’ |

Some counterevidence to a DP analysis is found in the fact that these configurations might be pronominalized with the neuter clitic

lo or the neuter demonstrative

eso, as though they were a sentence:

| (34) | A: | ¡La de veces que lloré este año! |

| | | ‘How many times I cried this year!’ |

| | B: | Ya me lo dijiste ayer eso. |

| | | ‘You told me that yesterday’ |

What seems to be at work here is that the verb of communication

decir ‘tell’ typically selects propositional arguments, even so, it can still select DPs as in

decir la verdad ‘tell the truth’ or

decir mentiras ‘tell lies.’

7 The reason why the sequence

«La de…» might not be replaced with

la or another clitic is that it is headed by a quantifier, and hence lacks referential properties. When the DP contains a referential

cantidad as in (14) or (35a) below, agreement with the head noun is indeed possible, but when

cantidad is the head quantifier of a pseudopartitive this option is ruled out (35b).

| (35) | a. | La cantidadi de inscriptos en el examen ya me lai has dicho |

| | | ‘The number of students enrolled in the test, you have already told me’ |

| | b. | ¡(Una) cantidad de veces te lo/*la he mencionado! |

| | | ‘I’ve mentioned this so many times!’ |

Another argument in favor of the hypothesis that these sentences entail some

wh-movement, as that found in the relative clauses in (36), comes from

Torrego’s (

1988) observation that nominal exclamatives (37a) license parasitic gaps due to the presence of the

wh- operator, which, in our case (37b), would be the relativizer

que heading the dependent clause.

| (36) | María me dio el libro quei Juan devolvió ___i sin mirar ___i. |

| | ‘Maria gave me the book that John returned without reading’ |

| (37) | a. | ¡Los libros quei Juan devolvió ___i sin mirar ___i! |

| | | ‘The books that John returned without reading!’ |

| | b. | ¡La de libros quei Juan devolvió ___i sin mirar ___i! |

| | | ‘How many books that John returned without reading!’ |

Let us suppose that in (37b) the underlying structure is clausal and that

la de libros is a constituent that moves to a Focus position before the complementizer

que. If this were the case, the sentences in (38) should be ungrammatical, for the simple reason that, as is assumed in the bibliography (

Rizzi 1997), foci do not tend to precede topics, as those italicized in the examples below.

8| (38) | a. | ¡La | de | especialistas | que, | sobre | ese | tema,

| sabe | poco y nada! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | specialists | that | about | that | topic | knows | little and nothing |

| | | ‘How many specialists know very little about that topic!’ |

| | b. | ¡La | de | hospitales | que, | a | la | hora | de | una | urgencia,

| están | cerrados! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | hospitals | that | to | the | hour | of | an | emergency | are | closed |

| | | ‘How many hospitals are closed in an emergency!’ |

A plausible objection to our analysis could be that these sentences reject other foci after

que, in view of the fact that these are not recursive within the same clausal domain.

| (39) | a. | *¡La | de | temas | que | A | JUAN | le | encantan |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | songs | that | to | John | CL | loves |

| | | ‘How many specialists know very little about that topic!’ |

| | b. | *¡La | de | veces | que | MARÍA | se | lastimó, | no | Juan. | |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | times | that | Mary | CL | hurt | not | John | |

The ungrammaticality of (39) has nothing to do with the lack of foci recursivity, however, but with the fact that the clause headed by

que is a relative clause. As pointed out by

Leonetti and Escandell-Vidal (

2017), restrictive relatives provide descriptive information that facilitate the identification of the referent of the NP, operating as predicates that narrow down the denotation of the antecedent. In this sense, they contribute presupposed, non-controversial information, which is part of the participants’ common ground. Even though these clauses might contain topics, as revealed by (38), they constitute syntactic environments which lack any internal informational domain, as they are associated with assertions and at-issue topics.

In connection with this point, a quirky feature of the relative clauses under consideration is their similarity to those clauses found in cleft sentences. In both cases, in (40) and (41), it is possible to identify, on the one hand, a preposed focalized constituent, written in capital letters, accented and with a higher pitch, and, on the other, a relative clause in final position, whose information and content are presupposed and taken for granted. In both cases, what is more, complex relative pronouns can be used.

| (40) | a. | ¡La | de | PROBLEMAS | con | los | que | tuve | que | lidiar! |

| | | Art.Fem.Sg | of | problems | with | the | that | had | that | deal |

| | | ‘How many problems I had to deal with!’ |

| | b. | Fueron | ESOS | PROBLEMAS | con | los | que | tuve | que | lidiar, | no | estos |

| | | Were | those | problems | with | the | that | had | that | deal | not | these |

| | | ‘It was those problems I had to deal with, not these’ |

Another contact point between cleft sentences and our data is that the relative clauses they are made up of are not prototypical. In the case of cleft sentences, as

Di Tullio (

2014) claims, the anomaly is concerned with the fact that they can modify a proper noun with unique reference (e.g.,

Fue A JUAN que echaron de la oficina, ‘It was John that was fired from the office’) and even prepositional phrases, among other categories which are not nominal (e.g.,

Fue EN LA FIESTA que encontraron el cuerpo, ‘It was at the party that the body was found’). As for

«La de…», it deviates from canonical relative clauses in that the latter do not trigger subject–auxiliary inversion, whereas

«La de…» apparently does, albeit the oddity of (43) is not straightforward for all speakers:

| (42) | a. | Los libros que el profesor me prestó son muy interesantes |

| | | The books that the teacher me lent are very interesting |

| | b. | Los libros que me prestó el profesor son muy interesantes |

| | | The books that me lent the teacher are very interesting |

| | ‘The books that the teacher lent me are very interesting’ |

| (43) | ?¡La | de | libros | que | el | profesor | me | prestó! |

| | Art.Fem.Sg | of | books | that | the | teacher | CL | lent |

| | (cf. ¡La de libros que me prestó el profesor!) |

Additionally, while most of the time we can dispose of a restrictive relative clause and obtain a grammatical utterance, with

«La de…» such an omission is not available.

| (44) | Los libros (que el profesor me prestó) son muy interesantes |

| | ‘The books (that the teacher lent me) are very interesting’ |

| (45) | ¡La de libros *(que me prestó el profesor) es de no creer! |

| | ‘I can’t believe how many books *(the teacher lent me)’ |

In this sense, this type of relative clauses resembles

emphatic relatives (

Plann 1984;

Gutiérrez-Rexach 1999;

Brucart 1999), whose main characteristic is that their head and

que can be replaced with an equivalent exclamative operator. In the examples below, the relative clause cannot be dispensed with, and the subject tends to appear post-verbally when it is not emphatic.

| (46) | a. | ¡Lo difícil que es el examen! (=¡Cuán difícil es el examen!) |

| | | ‘How difficult the exam is!’ |

| | b. | ¡Los disparates que dice tu novio! (=¡Qué disparates que dice tu novio!) |

| | | ‘What nonsense your boyfriend says!’ |

These differences are aligned with

Carlson’s (

1977) proposal that a number of constructions that have the essential

prima facie appearance of defining relative clauses, upon careful examination, do not easily fall into the traditional binary classification of relatives.

The author labelled these constructions

amount relatives, as amounts are part of their syntactic and semantic make up.

Grosu and Landman (

2017) call these and other kindred constructions

maximalizing relatives, while

Heim (

1987) calls them

degree relatives. Said structures are argued to quantify over a complete set of entities and encode amounts, cardinalities, durations, weights, distances, etc. Following Grosu and Landman’s classification, our data could be classified as

d(egree)-headed relatives, as the relative clause is headed by a degree head, which was originally the noun

cantidad and is now the quantifier

la (see

Section 4). If this line of reasoning is on the right track, the exclamative flavor attributed to these configurations in

Section 2.2 can easily be derived.

Torrego (

1988) observes that the amount reading emerges by dint of a null operator in the relative clause, which moves in LF from a clause internal position to the left periphery and has scope over its antecedent, the DP, which will determine its amount interpretation. In line with

Torrego (

1988), we also believe that the relation between the amount relative and the antecedent (the pseudopartitive structure described in

Section 2.1) is predication, inasmuch as the subordinate clause allows us to narrow down the scope of reference of the possible entities denoted by the antecedent, that is, the extension of the set defined by the noun in the tail of the pseudopartitive.

The subject–predicate relation can be observed not only in the paraphrase of this construction below, but also in others expressing a similar qualifying or quantifying meaning (see

Saab 2004;

Villalba and Bartra 2010, for a detailed analysis of the latter).

| (48) | a. | ¡La de libros que compró Juan! → Juan compró muchos libros |

| | | ‘How many books John bought! → John bought many books’ |

| | b. | Me | sorprende | [lo | lindo | de | la | casa] | → | La casa | es | linda |

| | | CL1.Sg | surprises | Art. | nice | of | the | house | | the house | is | nice |

| | | ‘It surprises me how nice the house is! → The house is nice’ |

| | c. | El | idiota | de | tu | novio | → | Tu | novio | es | un idiota |

| | | The | idiot | of | your | boyfriend | | Your | boyfriend | is | an idiot |

| | | ‘That idiot of your boyfriend → Your boyfriend is an idiot |

Following

Villalba and Bartra’s (

2010) analysis of (48b), in (48a) the subject–predicate relation happens to be altered due to information packaging and discourse-related issues: the QP

la de libros constitutes the focus of these constructions and the relative clause the background information. Evidence in favor of this comes from the impossibility of associating the relative with focus particles such as

solo ‘only’ (49a) and from the ungrammaticality caused by the presence of non-specific quantifiers such as

cualquiera (49b) or excess quantifiers such as

demasiados (49c), which are known to reject background or topic positions.

| (49) | a. | *¡La de libros que sólo compró Juan! |

| | | ‘How many books John only bought!’ |

| | b. | ?*¡La de libros que lee cualquier estudiante! |

| | | ‘How many books any student reads!’ |

| | c. | *¡La de libros que leen demasiados estudiantes! |

| | | ‘How many books too many students read!’ |

All things considered, it is possible to conclude that the clause that restricts the antecedent in the pseudopartitive is ‘relatively’ relative or, at least, different from the relatives found in DPs whose semantic import and force are not exclamative. This anomaly is nothing but an epi-phenomenon of the chimeric and hybrid nature of these constructions, which, as we have attempted to prove throughout this section, are halfway between clauses and noun phrases.