Abstract Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect across Development in a Structurally Biased Language

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Accounts of Structural Priming

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Design

2.1.2. Sentence Stimuli

2.1.3. Visual Stimuli

2.2. Procedure

Coding of Priming Data

3. Results

3.1. General Bias for the German DO Structure

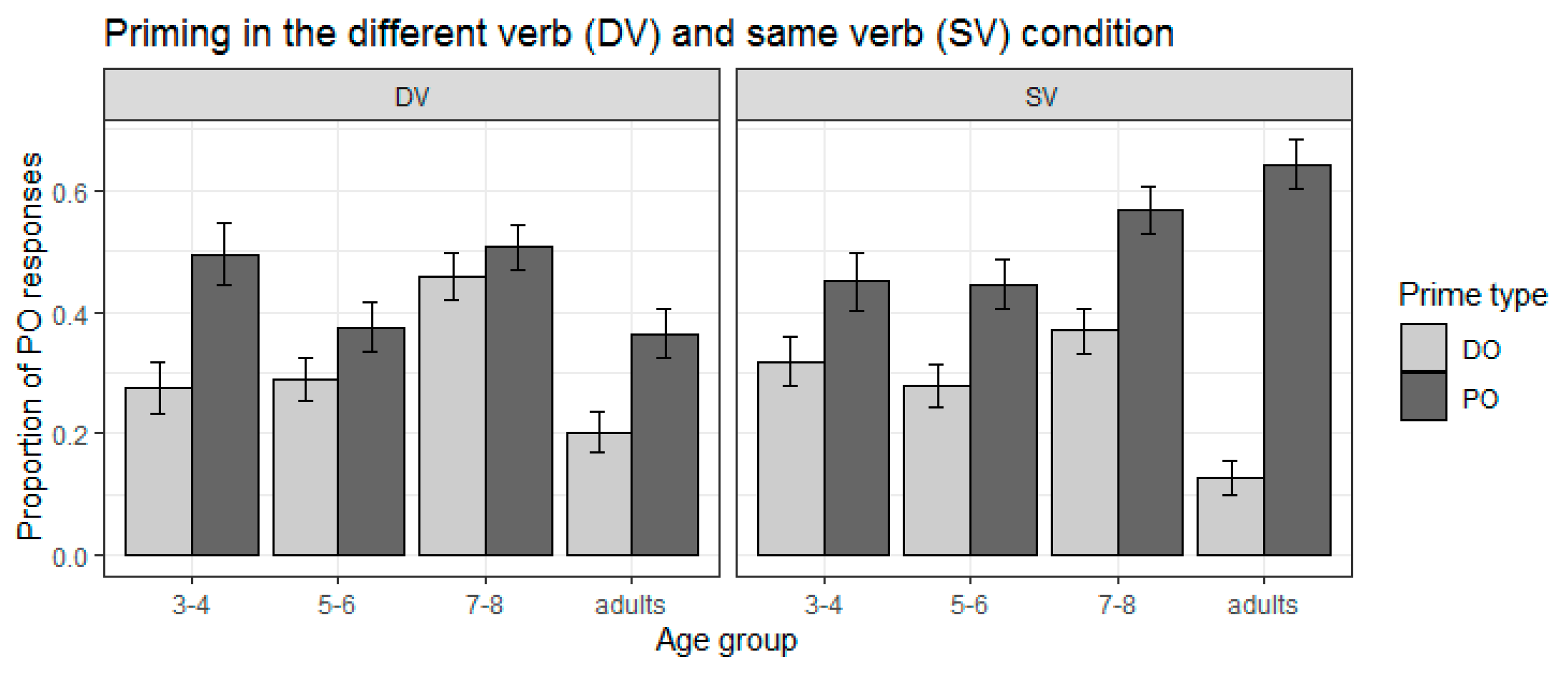

3.2. Immediate Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect

Priming Effects and the Lexical Boost within Each Age Group

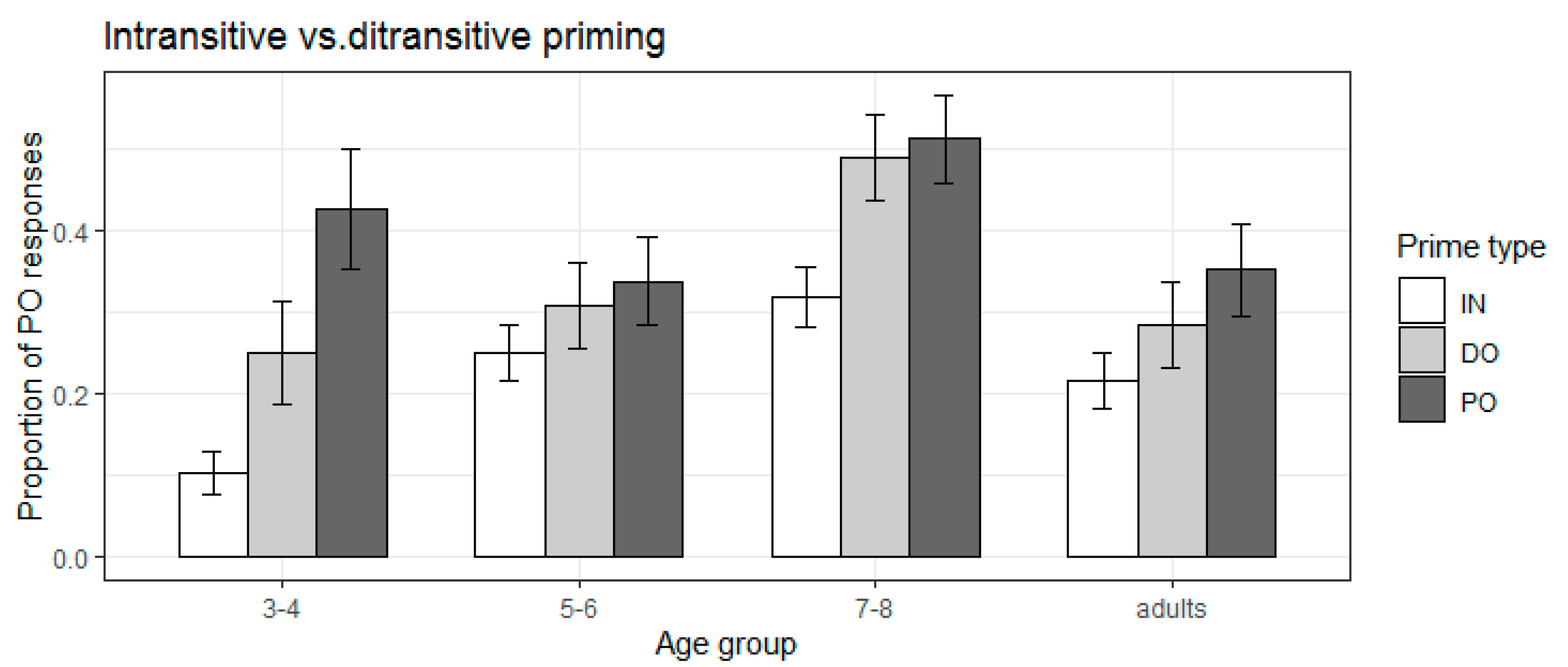

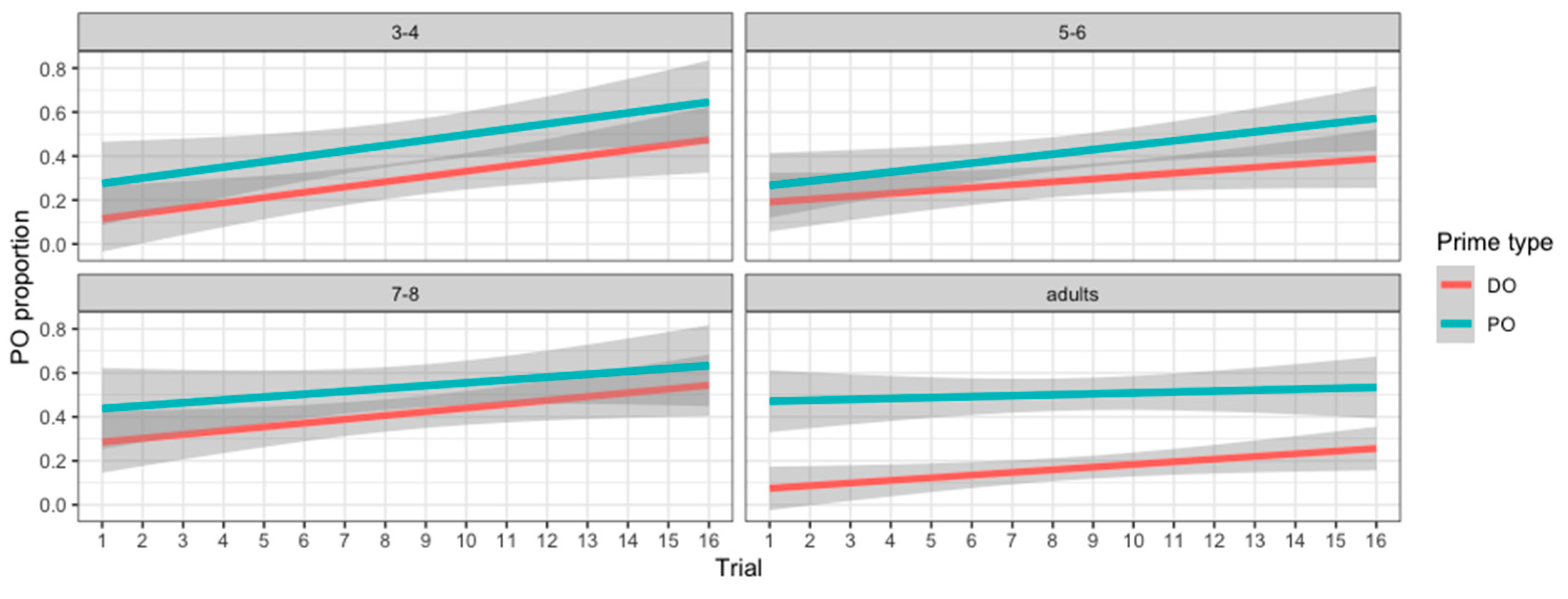

3.3. Priming Relative to the Baseline Pretest and Cumulative Priming

4. Discussion

4.1. Initial Structural Representations in Children

4.2. Abstract Immediate Structural Priming Effects

The Lexical Boost Effect and Its Development across Age

4.3. Surprisal Effects and Implicit Learning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Experimental Items

| German | English |

| Dora gibt Boots den (Hasen/Frosch)/den (Hasen/Frosch) an Boots Dora schwimmt. | Dora is giving Boots the (rabbit/frog)/the (rabbit/frog) to Boots Dora is swimming. |

| Dora bringt Boots den (Hasen/Frosch)/den (Hasen/Frosch) zu Boots | Dora is bringing Boots the (rabbit/frog)/the (rabbit/frog) to Boots |

| Dora verkauft Boots den (Papagei/Hund)/den (den Papagei/Hund) an Boots Dora springt. | Dora is selling Boots the (parrot/dog)/the (parrot/dog) to Boots Dora is jumping. |

| Dora schickt Boots den (Papagei/Hund)/den (den Papagei/Hund) zu Boots | Dora is sending Boots the (parrot/dog)/the (parrot/dog) to Boots |

| Jake gibt Izzy den (Schmetterling/Papagei)/den (Schmetterling/Papagei) an Izzy | Jake is giving Izzy the (butterfly/parrot)/the (butterfly/parrot) to Izzy |

| Jake bringt Izzy den (Schmetterling/Papagei)/den (Schmetterling/Papagei) zu Izzy Jake tanzt. | Jake is bringing Izzy the (butterfly/parrot)/the (butterfly/parrot) to Izzy Jake is dancing. |

| Jake verkauft Izzy den (Fisch/Frosch)/den (Fisch/Frosch) an Izzy Jake fliegt. | Jake is selling Izzy the (fish/frog)/the (fish/frog) to Izzy Jake is flying. |

| Jake schickt Izzy den (Fisch/Frosch)/den (Fisch/Frosch) zu Izzy | Jake is sending Izzy the (fish/frog)/the (fish/frog) to Izzy |

| Wendy gibt Bob den (Hund/Hasen)/den (Hund/Hasen) an Bob Wendy saugt. | Wendy is giving Bob the (dog/rabbit)/the (dog/rabbit) to Bob Wendy is (vacuum) cleaning. |

| Wendy bringt Bob den (Schmetterling/Hasen)/den (Schmetterling/Hasen) zu Bob | Wendy is bringing Bob the (butterfly/rabbit)/the (butterfly/rabbit) to Bob |

| Wendy verkauft Bob den (Hund/Hasen)/den (Hund/Hasen) an Bob | Wendy is selling Bob the (dog/rabbit)/the (dog/rabbit) to Bob |

| Wendy schickt Bob den (Schmetterling/Hasen)/den (Schmetterling/Hasen) zu Bob Wendy schaukelt. | Wendy is sending Bob the (butterfly/rabbit)/the (butterfly/rabbit) to Bob Wendy is swinging. |

| Micky gibt Minnie den (Fisch/Schmetterling)/den (Fisch/Schmetterling) an Minnie Micky läuft. | Micky is giving Minnie the (fish/butterfly)/the (fish/butterfly) to Minnie Micky is walking. |

| Micky bringt Minnie den (Fisch/Hund)/den (Fisch/Hund) zu Minnie | Micky is bringing Minnie the (fish/dog)/the (fish/dog) to Minnie |

| Micky verkauft Minnie den (Fisch/Schmetterling)/den (Fisch/Schmetterling) an Minnie | Micky is selling Minnie the (fish/butterfly)/the (fish/butterfly) to Minnie |

| Micky schickt Minnie den (Fisch/Hund)/den (Fisch/Hund) zu Minnie Micky winkt. | Micky is sending Minnie the (fish/dog)/the (fish/dog) to Minnie Micky is waving. |

| 1 | Initially, we did not intend to investigate cumulative priming effects. However, an unusual effect in the results led us to running an analysis which pointed towards cumulative effects. Because this analysis may considerably contribute to child priming research, we decided to include cumulative effects as an additional research question in this paper but because this hypothesis was not determined a priori it should be considered exploratory. |

| 2 | In contrast to our design, Rowland et al. (2012) included ‘Verb Condition’ as a between-subjects variable, in order to reduce the number of items presented to each child. We opted to follow Peter et al. (2015), who adapted the typical design used in adult priming studies, using as many within-participant variables as possible such that each participant would be exposed to all experimental conditions. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | For a justification for the use of optimizers in such analyses, see Darmasetiyawan et al. (2022) and Linck and Cunnings (2015). |

| 5 | Effects of ‘age group’ are based on a sum contrast, with each age group getting compared to the grand mean of all four groups (based on Schad et al. 2020). |

References

- Adler, Julia. 2011. Dative Alternations in German: The Argument Realization Options of Transfer Verbs. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, Manabu, and Reiko Mazuka. 2014. The development of Japanese passive syntax as indexed by structural priming in comprehension. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 67: 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, Rolf H., Doug J. Davidson, and Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modelling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, Heike. 2006. The input-output relationship in first language acquisition. Language and Cognitive Processes 21: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencini, Giulia M.L., and Virginia V. Valian. 2008. Abstract sentence representations in 4-year-olds: Evidence from language production and comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, J. Kathryn. 1986. Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology 18: 355–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Kathryn, and Helga Loebell. 1990. Framing sentences. Cognition 35: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Kathryn, and Zenzi M. Griffin. 2000. The persistence of structural priming: Transient activations or implicit learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 129: 177–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Kathryn, Gary Dell, Franklin Chang, and Kristine H. Onishi. 2007. Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition 104: 437–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Kathryn, Helga Loebell, and Randal Morey. 1992. From conceptual roles to structural relations: Bridging the syntactic cleft. Psychological Review 99: 150–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, Silke, Sanjo Nitschke, and Evan Kidd. 2017. Priming the comprehension of German relative clauses. Language Learning and Development 13: 241–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branigan, Holly P., and Janet F. McLean. 2016. What children learn from adults’ utterances: An ephemeral lexical boost and persistent syntactic priming in adult-child dialogue. Journal of Memory and Language 91: 141–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branigan, Holly P., and Katherine Messenger. 2016. Consistent and cumulative effects of syntactic experience in children’s sentence production: Evidence for error-based implicit learning. Cognition 157: 250–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branigan, Holly P., Janet F. McLean, and Manon W. Jones. 2004. A blue cat or a cat that is blue? Evidence for abstract syntax in young children’s noun phrases. Paper presented at the 29th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD), Boston, MA, USA, November 5–7; Edited by Alejna Brugos, Manuella R. Clark-Cotton and Seungwan Ha. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Branigan, Holly P., Martin J. Pickering, and Alexandra A. Cleland. 1999. Syntactic priming in written production: Evidence for rapid decay. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 6: 635–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branigan, Holly P., Martin J. Pickering, and Alexandra A. Cleland. 2000a. Syntactic co-ordination in dialogue. Cognition 75: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branigan, Holly P., Martin J. Pickering, Andrew J. Stewart, and Janet F. McLean. 2000b. Syntactic priming in spoken production: Linguistic and Temporal interference. Memory & Cognition 28: 1297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Callies, Marcus, and Konrad Szczesniak. 2008. Argument realization, information status and syntactic weight—A learner-corpus study of the dative alternation. In Fortgeschrittene Lernervarietaten. Korpuslinguistik und Zweitspracherwerbsforschung [Advanced Learner Varieties. Corpus Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition Research]. Edited by Patrick Grommes and Maik Walter. Tubingen: Niemeyer, pp. 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, Maria N., Roger P. G. van Gompel, and Laura J. Wakeford. 2019. An investigation into the lexical boost with non-head nouns. Journal of Memory and Language 108: 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Franklin, Gary S. Dell, and Kathryn Bock. 2006. Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review 113: 234–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Franklin, Gary S. Dell, J. Kathryn Bock, and Zenzi M. Griffin. 2000. Structural priming as implicit learning: A comparison of models of sentence production. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 29: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Franklin, Marius Janciauskas, and Hartmut Fitz. 2012. Language adaptation and learning: Getting explicit about implicit learning. Language and Linguistics Compass 6: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, Alexandra A., and Martin J. Pickering. 2003. The use of lexical and syntactic information in language production: Evidence from the priming of noun-phrase structure. Journal of Memory and Language 49: 214–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contemori, Carla, and Adriana Belletti. 2023. Relatives and passive object relatives in Italian-speaking children and adults: Intervention in production and comprehension. Applied Psycholinguistics 35: 1021–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmasetiyawan, I. Made Sena, Kate Messenger, and Ben Ambridge. 2022. Is passive priming really impervious to verb semantics? A high-powered replication of Messenger et al. (2012). Collabra: Psychology 8: 31055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vaere, Hilde, Ludovic De Cuypere, and Klaas Willems. 2018. Alternating constructions with ditransitive geben in present-day German. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 17: 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenhaus, Heiner. 2004. Minimalism, Features and Parallel Grammars: On the Acquisition of German Ditransitive Structures. Ph.D. thesis, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeiss, Sonja, Susanne Bartke, and Harald Clahsen. 2006. Structural and lexical case in child German: Evidence from language-impaired and typically developing children. Language Acquisition 13: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Victor S., and Kathryn J. Bock. 2006. The Functions of Structural Priming. Language and Cognitive Processes 21: 1011–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, Alex B., T. Florian Jaeger, Thomas A. Farmer, and Ting Qian. 2013. Rapid expectation adaptation during syntactic comprehension. PLoS ONE 8: e77661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, Susanna. 2006. A Comparison of Syntactic Representation and Processing in First and Second Language Production. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, May. [Google Scholar]

- Foltz, Anouschka, Kristina Thiele, Dunja Kahsnitz, and Prisca Stenneken. 2015. Children’s syntactic-priming magnitude: Lexical factors and participant characteristics. Journal of Child Language 42: 932–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez, Perla B., and Priya M. Shimpi. 2015. Structural priming in Spanish as evidence of implicit learning. Journal of Child Language 43: 207–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez, Perla B., Priya M. Shimpi, Heidi R. Waterfall, and Janellen Huttenlocher. 2009. Priming a perspective in Spanish monolingual children: The use of syntactic alternatives. Journal of Child Language 36: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, Jeffrey, and Frank Keller. 2010. Corpus evidence for age effects on priming in child language. Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Portland, OR, USA, August 11–14; vol. 32, pp. 218–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, Stefan T. 2005. Syntactic priming: A corpus-based approach. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 34: 365–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartsuiker, Robert J., and Herman H. J. Kolk. 1998. Syntactic persistence in Dutch. Language and Speech 41: 143–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartsuiker, Robert J., Sarah Bernolet, Sofie Schoonbaert, Sara Speybroeck, and Dieter Vanderelst. 2008. Syntactic priming persists while the lexical boost decays: Evidence from written and spoken dialogue. Journal of Memory and Language 58: 214–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havron, Naomi, Camila Scaff, Maria J. Carbajal, Tal Linzen, Axel Barrault, and Anne Christophe. 2020. Priming syntactic ambiguity resolution in children and adults. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 35: 1445–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Dong-Bo. 2014. Structural priming as learning: Evidence from mandarin-learning five-year-olds. Lang. Acquis 21: 156–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttenlocher, Janellen, Marina Vasilyeva, and Priya Shimpi. 2004. Syntactic priming in young children. Journal of Memory and Language 50: 182–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, T. Florian. 2008. Categorical data analysis: Away from ANOVAs (transformation or not) and towards logit mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 434–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, T. Florian, and Neal E. Snider. 2013. Alignment as a consequence of expectation adaptation: Syntactic priming is affected by the prime’s prediction error given both prior and recent experience. Cognition 127: 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, T. Florian, and Neal Snider. 2008. Implicit learning and syntactic persistence: Surprisal and cumulativity. Paper presented at the 30th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (CogSci08), Washington, DC, USA, July 23–26; Austin: Cognitive Science Society, pp. 1061–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kaan, Edith, and Eunjin Chun. 2018. Priming and adaptation in native speakers and second-language learners. Bilingualism 21: 228–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschak, Michael P., and Kristin L. Borreggine. 2008. Is long-term structural priming affected by patterns of experience with individual verbs? Journal of Memory and Language 58: 862–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschak, Michael P., Timothy J. Kutta, and John L. Jones. 2011. Structural priming as implicit learning: Cumulative priming effects and individual differences. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 18: 1133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kholodova, Alina, and Shanley Allen. 2023. The dative alternation in German: Structural preferences and verb bias effects. In Ditransitive Constructions in Germanic Languages. Edited by Eva Zehentner, Melanie Röthlisberger and Timothy Coleman. Ditransitives in Germanic languages: Synchronic and diachronic aspects. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 264–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, Evan. 2012a. Implicit statistical learning is directly associated with the acquisition of syntax. Developmental Psychology 48: 171–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, Evan. 2012b. Individual differences in syntactic priming in language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics 33: 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarage, Shanthi, Seamus Donnelly, and Evan Kidd. 2022. Implicit learning of structure across time: A longitudinal investigation of syntactic priming in young English-acquiring children. Journal of Memory and Language 127: 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmden, Friederike M. 2013. Die Rolle sozialer Interaktion bei der Wiederholung syntaktischer Strukturen: Eine Studie zur Videopräsentation und Sprecheranzahl bei Vierjährigen. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Lieven, Elena, and Sabine Stoll. 2013. Early communicative development in two cultures. Human Development 56: 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, Jared A., and Ian Cunnings. 2015. The utility and application of mixed-effects models in second language research. Language Learning 65: 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWhinney, Brian, ed. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. Part 1: The CHAT Transcription Format, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, Claudia, and Carla Contemori. 2019. The Production of Object Relative Clauses in Italian-Speaking Children: A Syntactic Priming Study. Paper presented at the 43th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD), Boston, MA, USA, November 2–4; Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 39–403. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, Katherin. 2021. The persistence of priming: Exploring Long-lasting Syntactic Priming Effects in Children and Adults. Cognitive Science 45: e13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, Katherine, and Sophie M. Hardy. 2017. Exploring the Lexical Boost to Syntactic Priming in Children and Adults. [Poster presentation]. Lancaster: Architectures and Mechanisms of Language Processing (AMLaP). [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, Katherine, Holly P. Branigan, and Janet F. McLean. 2011. Evidence for (shared) abstract structure underlying children’s short and full passives. Cognition 121: 268–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Louise C., and Cristoph Scheepers. 2015. Syntactic priming and the lexical boost in preschool children. Open Access Manuscript. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Mika. 1990. Repetition priming in children and adults: Age-related dissociation between implicit and explicit memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 50: 462–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, Michelle, Franklin Chang, Julian M. Pine, Ryan Blything, and Caroline F. Rowland. 2015. When and how do children develop knowledge of verb argument structure? Evidence from verb bias effects in a structural priming task. Journal of Memory and Language 81: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, Martin J., and Holly P. Branigan. 1998. The Representation of Verbs: Evidence from Syntactic Priming in Language Production. Journal of Memory and Language 39: 633–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proost, Kristel. 2014. Ditransitive transfer constructions and their prepositional variants in German and Romanian: An empirical survey. In Komplexe Argumentstrukturen. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 19–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proost, Kristel. 2015. Verbbedeutung. Konstruktionsbedeutung oder beides? Zur Bedeutung deutscher Ditransitivstrukturen und ihrer präpositionalen Varianten. In Argumentstruktur zwischen Valenz und Konstruktion. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto, pp. 157–76. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Reitter, David, Frank Keller, and Johanna D. Moore. 2011. A computational cognitive model of syntactic priming. Cognitive Science 35: 587–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, Caroline F., Franklin Chang, Ben Ambridge, Julian M. Pine, and Elena V. M. Lieven. 2012. The development of abstract syntax: Evidence from structural priming and the lexical boost. Cognition 125: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, Ceri, Elena Lieven, Anna L. Theakston, and Michael Tomasello. 2003. Testing the abstractness of children’s linguisic representations: Lexical and structural priming of syntactic constructions in young children. Developmental Science 6: 557–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, Ceri, Elena Lieven, Anna Theakston, and Michael Tomasello. 2006. Structural priming as implicit learning in language acquisition: The persistence of lexical and structural priming in 4-year-olds. Language Learning and Development 2: 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, Daniel J., Shravan Vasishth, Sven Hohenstein, and Reinhold Kliegl. 2020. How to capitalize on a priori contrasts in linear (mixed) models: A tutorial. Journal of Memory and Language 110: 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Christoph. 2003. Syntactic priming of relative clause attachments: Persistence of structural configuration in sentence production. Cognition 89: 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Christoph, Claudine N. Raffray, and Andriy Myachykov. 2017. The lexical boost effect is not diagnostic of lexically-specific syntactic representations. Journal of Memory and Language 95: 102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherger, Anna-Lena, Jasmin M. Kizirmak, and Kristian Folta-Schoofs. 2022. Ditransitive structures in child language acquisition: An investigation of production and comprehension in children aged five to seven. Journal of Child Language 50: 1022–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serratrice, Ludovica, Anne Hesketh, and Rachel Ashworth. 2015. The use of reported speech in children’s narratives: A priming study. First Language 35: 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimpi, Priya M., Perla B. Gámez, Janellen Huttenlocher, and Marina Vasilyeva. 2007. Syntactic Priming in 3- and 4-Year-Old Children: Evidence for Abstract Representations of Transitive and Dative Forms. Developmental Psychology 43: 1334–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprondel, Volker, Kerstin H. Kipp, and Axel Mecklinger. 2011. Developmental changes in item and source memory: Evidence from an ERP recognition memory study with children, adolescents, and adults. Child Development 82: 1938–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thothathiri, Malathi, and Jesse Snedeker. 2008a. Give and take: Syntactic priming during spoken language comprehension. Cognition 108: 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thothathiri, Malathi, and Jesse Snedeker. 2008b. Syntactic priming during language comprehension in three- and four-year-old children. Journal of Memory and Language 58: 188–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beijsterveldt, Liesbeth M., and Janet G. van Hell. 2009. Structural priming of adjective-noun structures in hearing and deaf children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 104: 179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gompel, Roger P. G., Laura J. Wakeford, and Leila Kantola. 2023. No looking back: The effects of visual cues on the lexical boost in structural priming. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 38: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyeva, Marina. 2012. Beyond syntactic priming: Evidence for activation of alternative syntactic structures. Child Language 39: 258–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeldon, Linda, and Mark Smith. 2003. Phrase structure priming: A short-lived effect. Language and Cognitive Processes 18: 431–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolleb, Anna, Antonella Sorace, and Marit Westergaard. 2018. Exploring the role of cognitive control in syntactic processing: Evidence from cross-language priming in bilingual children. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 8: 606–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, Rebecca. 2015. The acquisition of dative alternation by German-English bilingual and English monolingual children. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 5: 252–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chi, Sarah Bernolet, and Robert J. Hartsuiker. 2020. The role of explicit memory in syntactic persistence: Effects of lexical cueing and load on sentence memory and sentence production. PLoS ONE 15: e0240909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fixed Effect | β | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (intercept) | −0.89 | 0.29 | −3.10 | <0.01 | ** |

| prime type (DO vs. PO) | 1.20 | 0.18 | 6.55 | <0.001 | ** |

| verb condition (DV vs. SV) | 0.31 | 0.18 | 1.67 | 0.10 | |

| 3- to 4-year-olds (vs. grand mean) | −0.12 | 0.26 | −0.45 | 0.66 | |

| 5- to 6-year-olds (vs. grand mean) | −0.25 | 0.26 | −0.96 | 0.34 | |

| 7- to 8-year-olds (vs. grand mean) | 0.66 | 0.27 | 2.42 | 0.02 | * |

| prime type * verb condition | 0.76 | 0.30 | 2.50 | 0.01 | * |

| prime type * 3- to 4-year-olds | −0.29 | 0.28 | −1.05 | 0.29 | |

| prime type * 5- to 6-year-olds | −0.47 | 0.21 | −2.29 | 0.02 | * |

| prime type * 7- to 8-year-olds | −0.34 | 0.26 | −1.33 | 0.18 | |

| 3- to 4-year-olds * verb condition | −0.04 | 0.29 | −0.15 | 0.88 | |

| 5- to 6-year-olds * verb condition | −0.01 | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.98 | |

| 7- to 8-year-olds * verb condition | −0.35 | 0.30 | −1.18 | 0.24 | |

| prime type * 3- to 4-year-olds * verb condition | −1.22 | 0.48 | −2.55 | 0.01 | * |

| prime type * 5- to 6-year-olds * verb condition | −0.31 | 0.49 | −0.63 | 0.53 | |

| prime type * 7- to 8-year-olds * verb condition | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.68 |

| β | SE | z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age group | |||||

| 3–4 | |||||

| (intercept) | −1.04 | 0.36 | −2.94 | <0.01 | ** |

| prime type | 0.88 | 0.29 | 3.08 | 0.002 | ** |

| verb condition | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.69 | |

| prime type * verb condition | −0.22 | 0.58 | −0.35 | 0.73 | |

| 5–6 | |||||

| (intercept) | −1.16 | 0.42 | −2.77 | <0.01 | ** |

| prime type | 0.80 | 0.24 | 3.39 | <0.001 | *** |

| verb condition | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.92 | 0.36 | |

| prime type * verb condition | 0.73 | 0.55 | 1.32 | 0.18 | |

| 7–8 | |||||

| (intercept) | −0.21 | 0.45 | −0.46 | 0.65 | |

| prime type | 0.80 | 0.31 | 2.62 | <0.01 | ** |

| verb condition | −0.01 | 0.41 | −0.04 | 0.97 | |

| prime type * verb condition | 0.79 | 0.41 | 2.00 | 0.051 | |

| adults | |||||

| (intercept) | −1.01 | 0.26 | −3.84 | <0.001 | *** |

| prime type | 2.22 | 0.34 | 6.50 | <0.001 | *** |

| verb condition | 0.46 | 0.26 | 1.80 | 0.071 | |

| prime type * verb condition | 2.46 | 0.64 | 3.83 | <0.001 | *** |

| Age Group | Different Verb (DV) | Same Verb (SV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| 3–4 | 1.48 | 0.42 | 0.000 *** | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.01 * |

| 5–6 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 1.23 | 0.37 | 0.000 *** |

| 7–8 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 1.17 | 0.35 | 0.000 *** |

| adults | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.02 * | 3.26 | 0.46 | 0.000 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kholodova, A.; Peter, M.; Rowland, C.F.; Jacob, G.; Allen, S.E.M. Abstract Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect across Development in a Structurally Biased Language. Languages 2023, 8, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040264

Kholodova A, Peter M, Rowland CF, Jacob G, Allen SEM. Abstract Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect across Development in a Structurally Biased Language. Languages. 2023; 8(4):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040264

Chicago/Turabian StyleKholodova, Alina, Michelle Peter, Caroline F. Rowland, Gunnar Jacob, and Shanley E. M. Allen. 2023. "Abstract Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect across Development in a Structurally Biased Language" Languages 8, no. 4: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040264

APA StyleKholodova, A., Peter, M., Rowland, C. F., Jacob, G., & Allen, S. E. M. (2023). Abstract Priming and the Lexical Boost Effect across Development in a Structurally Biased Language. Languages, 8(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8040264