1. Introduction

This paper discusses how descriptions of a multiplicity of events are encoded in Macuxi (Cariban), a South American Indigenous language spoken in Brazil, Guyana and Venezuela. Cross-linguistically, several morphological strategies have been identified in the process of encoding a multiplicity of events, including affixation, vowel alternation and partial or full reduplication

1 (

Cusic 1981;

Lasersohn 1995;

Xrakovskij 1997). In previous work on Macuxi (

Carson 1982;

Abbott 1991), it was claimed that the iterative suffix -

pîtî (1) indicates a repetition of actions. In this literature, verbal reduplication (2) is mentioned but scarcely described, and is associated with the interpretation of multiple events.

| 1. | paapa | yei | ya’tî-pîtî |

| | father-erg | tree | cut-iter |

| | “Father cuts the tree repeatedly.” | (Abbott 1991, p. 118) |

| 2. | anî-patî-patî | João-ya | tuuke | teeka |

| pro-hit~hit | Joao-erg | many | time |

| | “Who has hit João often?” | (Carson 1982, p. 180) |

The multiplicity of actions or events has been treated with different terminology in the literature. Analogous to number in the nominal domain, distinguishing singularity and plurality, scholars have termed this as verbal number (

Corbett 2000), event plurality, iterativity (

Xrakovskij 1997), verbal plurality (

Cusic 1981), or pluractionality (

Newman 1980,

1990), which is the term we adopt in this paper. According to

Lasersohn (

1995),

Mattiola (

2019,

2020) and

Wood (

2007), pluractionality involves grammatical markers of event plurality associated with the verb, and these markers express the repetition of events in time or space, or across various participants.

Activities are verbs unfolding over a measurable time span, with no inherent end point, e.g., “to run”, while accomplishment verbs unfold over a measurable time span, with an end point, e.g., “to drown”. Achievements are punctual verbs with a terminal point, e.g., “to find”, while semelfactives are punctual verbs with no terminal point, e.g., “to knock”. Lastly, static verbs have no internal change, e.g., “to like”. This classification is useful, as it allows us to categorize verbs to distinguish finer differences between certain interpretations of plural events, considering their inherent temporal properties.

Across languages,

Aktionsart, or the lexical aspect of the verb, affects readings of plural situations. For example,

Abdolhosseini et al. (

2002) found that, by considering the lexical aspectual classes and the semantics of base verbs in Niuean (Polynesian), they could predict the meaning of a given reduplicated verb. Based on the patterns observed in cross-linguistic studies and formal approaches to this topic (such as

Lasersohn (

1995), discussed in

Section 4), this paper aims to expand on previous descriptions of this topic in Macuxi (

Abbott 1991;

Carson 1982;

Grund 2017) and address the following questions: what is the difference in the distribution and interpretation of the morpheme -

pîtî and reduplication in Macuxi? Does

Aktionsart have an impact on whether verbs can be reduplicated and on whether verbs can suffixed with the morpheme -

pîtî? Finally, what are the interpretations of reduplicated verbs, and for verbs with the -

pîtî suffix?

This paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we present a brief overview of the Macuxi language.

Section 3 introduces the tasks performed with Macuxi speakers to investigate the distribution and interpretation of the morpheme -

pîtî and reduplication in Macuxi.

Section 4 presents a formal analysis of both phenomena in the language, based on

Lasersohn (

1995),

Součková (

2011), and the literature on

Aktionsart. Finally,

Section 5 presents the results of this study against the typology of Cariban languages, based on the work of

Mattiola (

2019).

2. The Macuxi Language

The Macuxi language (ISO 639-1: mbc; Cariban), also referred to as Makushi, Makushí, Makuchi, Makussi, Makusi, Pemon, Teweya, or Teueia in the literature, is spoken in the northern Brazilian state of Roraima, the Rupununi region of Guyana and the Bolívar state of Venezuela. According to the Macuxi entry in Instituto Socioambiental’s Encyclopedia of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil (

Santilli 2018), the Macuxi population is estimated at 43,192, with 33,603 in Brazil (as of 2014), 9500 in Guyana (as of 2001) and 89 in Venezuela (as of 2011).

Macuxi belongs to the Cariban family, sharing similarities with other languages in the east–west geographic–linguistic group proposed by

Durbin (

1977), including Pemong (Taurepang), Akawaio and Arekuna (

Crevels 2012, p. 183).

Some Morphosyntactic Aspects of the Macuxi Language

Previous literature has diverged regarding Macuxi’s basic word order. While some authors claimed that the basic word order is OVS (

Abbott 1991;

Derbyshire and Pullum 1981;

Pullum 1981), other authors claim that the basic word order is SOV (

Carson 1982). Typologically,

Gildea (

1998) also acknowledges these discrepancies, and classifies Macuxi under the “Progressive” system, with a nominative word order: [OV]A/VS.

3 Abbott (

1991) hypothesizes that Carson’s postulation about the SOV word ordering in Macuxi could be an effect from working with bilingual speakers of Portuguese, which has a word order in which the subject appears first. Both Carson and Abbott also attribute the variation in Macuxi word order to discourse pragmatics, where a subject can be fronted for emphasis.

Carson and Abbott describe Macuxi as having an ergative–absolutive system, in which the ergative suffix -

ya occurs on transitive subjects such as

yenupanen, “teacher”, presented in (3), and on pronouns when they encode the subject of transitive verbs, such as

to- in (4).

| 3. | more-yamî | yenupa-‘pî | to’ | yenupa-nen-ya | |

| | child-pl | teach-pst | their | teach-s:nomlzr-erg | |

| | “Their teacher taught the children.” | (Abbott 1991, p. 83) |

| | | |

| 4. | mîîkîrî | yarî-‘pî | to-‘ya | |

| | 3:pro | carry-pst |

3:pro:pl-erg | |

| | “They carried him.” | | | (Abbott 1991, p. 25) |

Macuxi verbs are marked for person and number, aspect, and mode via affixes. The general Macuxi verb template is shown in

Table 2.

Macuxi has a prefix (i) that agrees in person with the subjects of intransitive verbs and the objects of transitive verbs. This is followed by the verbal stem (ii), before the subsequent suffix (iii), which tends to be an aspectual marker.

Abbott (

1991) lists such markers as follows: completed action (-

sa’), iterative (-

pîtî), reversative (-

ka), procrastinated action (-

tu’ka), conative (-

yonpa), ingressive (-

pia’tî), and terminative (-

aretî-

ka). Tense-marking (iv) occurs after the presence of any aspectual marking. This is followed by a suffix for case (v): the ergative -

ya is used with the subject of transitive verbs. The final possible suffix in the verbal template (vi) is for number agreement, such as with the collective suffix

-kon.

4In this paper, we focus on the distribution and interpretation of the suffix -

pîtî and reduplication. As previously mentioned, the -

pîtî suffix (

Abbott 1991), also characterized as an iterative morpheme (

Carson 1982), occurs immediately after the verbal stem (5) and before the completed aspect or past tense (6). According to Abbott, it expresses repeated or habitual action, when occurring with

-ʔpɨ, “past”. For instance, Abbott describes (6) as only interpretable as a habitual action of worshipping in the past.

| 6. | mîîkîrî | i-n-koneka-‘pî | yapurî-pîtî-pî | to’ya |

| |

3.pro | 3-obj.nmlz-make-pst | praise-iter-pst |

3.pro.pl-erg |

| | “They used to worship that which he made.” | (Abbott 1991, p. 118) |

Abbott (

1991, p. 34) highlights the existence of “verb repetition” and describes this process as a grammatical strategy that indicates the continuativity of an event, occurring over a period of time or distance. We refer to this phenomenon as verbal reduplication

5. For instance, in (7), the verb for “to go” is reduplicated in order to indicate a continuative, repetitive action, as is the verb for “to remain” in (8).

| 7. | moropai | attî-‘pî | attî-‘pî | attî-‘pî | a’nai | tîrî-‘pî | see pata | e’ma ta |

| | and | go-pst | go-pst | go-pst | corn | put-pst | this place | road in |

| | | e’ma ta | e’ma ta | | | |

| | | road in | road in | | | |

| | “And he went and went putting corn here in the road (as he went along).” | |

| | (Abbott 1991, p. 34) |

| 8. | moro | aa-ko’mamî-‘pî | aa-ko’mamî-‘pî | t-ekkari | t-onpa-i |

| | there | 3-remain-pst | 3-remain-pst | 3:reflx-food | 3:reflx-taste-advblzr |

| | | pra | asakî’n | e wei | |

| | | neg | two | day | |

| | “There he remained, not eating his food for two days.” | (Abbott 1991, p. 34) |

Carson’s (

1982) grammar further illustrates verbal reduplication. In (9), the verbal stem

patî occurs twice. This example is not contextualized, and from the translation, the interpretation of the reduplicated verb is unclear. Additionally, the use of the adverb

tuuke teeka, “number of times, often”, is compatible with the interpretation of the verb indicating a repetition of events:

| 9. | anï-patï-patï | João-ya | tuuke | teeka6 | |

| | pro-hit~hit | Joao-erg | many | time | |

| | “Who has hit João often?” | (Carson 1982, p. 180) |

Beyond the examples found in the existing grammars, there is a lack of in-depth descriptions of the use and possible interpretations of reduplication in Macuxi. In her ethnographic study on the movements of Macuxi people along the southern Guyana border,

Grund (

2017) discusses the use of reduplication in her consultants’ narratives. Drawing links to verbal art and poetic discourse, Grund observes that reduplication seems to be very common in descriptions of movement in Macuxi, and that this construction is associated with intensity, habituality and continuative action (

Grund 2017, pp. 204–5, based on

Sherzer 2002, pp. 19–21).

In

Section 3, we discuss the strategies employed in context-based elicitation sessions to investigate the distribution and interpretations of reduplicated verbs and of the -

pîtî suffix.

4. A Formal Analysis of Macuxi Pluractionals

4.1. An Analysis of pîtî

We have seen in the previous sections that the multiplicity of events in Macuxi can be expressed via the -

pîtî morpheme. In this section, we provide an analysis of this morpheme in light of Lasersohn’s account of pluractionality (

Lasersohn 1995). According to Lasersohn, pluractional markers are morphemes which “attach to the verb to indicate a multiplicity of actions, whether involving multiple participants, times, or locations. Pluractional markers do not reflect the plurality of a verb’s arguments so much as the plurality of the verb itself” (

Lasersohn 1995, pp. 240–41). Given its distribution and interpretation, we analyze -

pîtî as a pluractional marker.

Under Lasersohn’s analysis, a verb affixed with a pluractional marker would be interpreted as in (23):

| 23. | V-PA(X) ⇔ ∀e, e’ ∈ X[V(e) & ¬τ(e) o τ(e’)] & |

| | ∃t[(between(t, τ(e), τ(e’)) & ¬∃(e’’)[V(e’’) & t= τ(e’’)]) & card(X) ≥ n |

A pluractional verb is true of a group of events X, if and only if there are at least n events in X, and every event e in X holds true of the corresponding “singular” verb V, does not overlap with any other event e’ in X, and is separated from e’ by an interval t such that no other event of type V occurs at t.

We now extend this analysis to Macuxi. Consider example (24):

| 24. | Context: Maria washed three shirts: one shirt in the morning, one in the afternoon and one in the evening. |

| | Maria-ya | pon | runa-pîtî-pî | | | |

| | Maria-erg | shirt | wash-iter-pst | | | |

| | Maria washed shirts (repeatedly). | |

| 25. | runa-PA(X) ⇔ ∀e, e’ ∈ X[runa(e) & ¬τ(e) o τ(e’)] & |

| | ∃t[(between(t, τ(e), τ(e’)) & ¬∃(e’’)[runa(e’’) & t = τ(e’’)]) & card(X) ≥ n |

(25) states that runa-PA is true of X if and only if there are at least n events in X, and every event e in X is an event of washing that does not overlap with any other event e’ in X, and is separated from e’ by some interval t, such that no washing occurs at t.

4.2. An Analysis of Reduplicated Verbs

Lasersohn’s proposal, based on the event/phase and the distributivity parameters from

Cusic (

1981), works for the interpretations of the -

pîtî morpheme, as the event is distributed over time. However, its application to Macuxi reduplication is more complicated. While compatible with situations with multiple events (as suggested by the speakers’ translations and previous work on this topic), reduplication is generally associated with the intensity interpretation rather than the cardinality of events, as seen with the -

pîtî morpheme.

The issue with Lasersohn’s analysis is the lack of tools with which to account for intensity interpretations. An anonymous reviewer recommended that we adopt

Součková and Buba’s (

2008) revision of

Lasersohn (

1995) for Hausa pluractionals to account for the intensity interpretations associated with Macuxi reduplication. In their approach, the semantics of pluractionals contain a degree component, which replaces the cardinality component in Lasersohn’s formalization. Another key difference is in the treatment of verbs: whereas simple verbs refer to singular events in Lasersohn’s analysis, Součková and Buba treat simple verbs as number-neutral, such that they can refer to either singular or plural events. Separately, pluractional verbs can only refer to plural events.

In Hausa, pluractionality is marked via partial reduplication of the verb, and it can be used to express a plural event in which sub-events are distributed across participants, locations, or times (

Součková and Buba 2008, p. 135). Crucially, this ideally involves a vague and high number of participants, locations, or times. This is a productive derivational process that applies to all verbs, albeit with varying acceptability judgments from speakers. However, Součková and Buba focus on a specific subset of Hausa pluractionals, gradable verbs, which when reduplicated, generate intensity interpretations, as opposed to the prototypical distributive interpretations. These gradable verbs are mostly intransitives, as in (26).

| 26. | a. | naa/mun | gàji | | |

| | |

1sg/1pl.pf | be_tired | | |

| | | “I am / we are tired” |

| | b. | mun | gàg-gàji | |

| | |

1pl.pf | red-be_tired | |

| | | “We are all very tired” |

| | c. | #naa | gàg-gàji | | |

| | |

1sg.pf | red-be_tired | | |

| | | Intended reading: “I am very tired” |

| | | (Součková and Buba 2008, p. 137) |

Based on these data, the authors modify Lasersohn’s proposal, replacing card(X) ≥ n with a degree component. The degree function allows access to larger sums of events from the verbal denotation. Furthermore, this function would encapsulate the vagueness of the number value. In Součková and Buba’s view, the denotation of a pluractional morpheme is as follows (

Součková and Buba 2008, p. 140):

| 27. | [[PA]] = λVλe.V(e) & e∉{At} & ∀e’,e’’ ⊂ e [V(e’) & V(e”) & ¬f(e’) o f(e’’) & |

| ∃x[between(x,f(e’),f(e’’)) & ¬∃e’’’ [V(e’’’) & x = f(e’’’)]] & ∃dh[(dh(V))(e)] |

| dh … degree function mapping an ordered set to a subset of it that contains all those elements that qualify as relatively high with respect to the given ordering. |

This allows them to expand the coverage of the analysis and account for both plurality and intensiveness, as in (28b).

| 28. | a. | yaa / | yâraa | sun | ruuɗèe |

| | |

3sg.pf / | children |

3pl.pf | be.confused |

| | | He was / (the children were) confused. |

| | b. | yâraa | sun | rur-rùuɗèe |

| | | hildren |

3pl.pf | red-be.confused |

| | | The children were very confused (beyond control, alarmed). (intensive) |

| | c. | * yaa | rur-ruuɗèe | |

| | |

3sg.pf | red-be.confused | |

| | | Intended interpretation: He is very confused. |

| | | (Součková and Buba 2008, p. 137) |

The core of Součková and Buba’s analysis is that the semantics of pluractionals in Hausa encode a degree component, which account for the “high degree” readings. While we agree that some form of degree component and vagueness might be necessary to account for the intensification interpretation, we are hesitant to adopt this analysis for Macuxi, as it centers gradability as a core component in interpreting multiple events. The reduplication in Macuxi appears to be distinct from the mostly intransitive, gradable cases in Hausa, especially since only a subset of Macuxi verbs allow reduplication. Furthermore, the intensification effect that arises with reduplicated verbs is supplementary to the multiplicity of events. Instead, we adopt Součková’s subsequent revision (

Součková 2011) of this approach, in which the meanings of pluractional Hausa constructions are attributed to interactions between different levels of meaning: (a) the core meanings of pluractional verbs (e.g., event plurality); (b) event anchoring (e.g., how a given language individuates events); and (c) “special” meanings of event plurality.

We analyze the intensification effect of Macuxi reduplication as an additional, “special” meaning.

Součková (

2011) provides several pieces of evidence that intensification is a peripheral (i.e., non-core) meaning that can potentially arise with a Hausa pluractional. Firstly, while the plurality meaning cannot be cancelled, the intensification interpretation can be cancelled for some speakers. Secondly, the intensification effect extends beyond gradable verbs (the basis of

Součková and Buba’s (

2008) analysis), as in (29). As opposed to degree modification, Součková posits that cases like (29) involve an emphasis on events that are marked (“an implication that the event was somehow more ‘serious’ or ‘abnormal’ in some way” (

Součková 2011, p. 192)).

| 29. | a. | Naa | tòokàree | shi | |

| | |

1sg.pf / | poke | him | |

| | | “I poked him.” |

| | | n.b. It can be gentle |

| | b. | Naa | tàt-tòokàree | shi |

| | |

1sg.pf / | red-poke | him |

| | | “I poked him.” |

| | | n.b. %repeatedly and with strength |

| | | (Součková 2011, p. 192) |

In sum, we adopt Součková’s approach to pluractional meaning by positing reduplication as an additional, “special” component of event plurality, in addition to the semantic contributions of the -pîtî morpheme. This is especially significant considering the limited verbs that permit reduplication in Macuxi, which we will now address.

4.3. A Commentary on the Aktionsart Effect on Acceptability of Reduplicated Verbs

In

Section 3, we showed that Macuxi semelfactives and activities tend to be reduplicated more than the other classes of verbs, and that reduplication is often found to encode the intensity of events.

Recall that we focused on two factors for the dynamic verbs in the translation task: telicity and durativity (

Table 1). A bounded or telic event has a natural end point. A durative event unfolds over a measurable time span, whereas a punctual event occurs in an instant. It should be noted here that we adopt the definition of semelfactives from

Smith (

1991). Smith posits semelfactives as a distinct category, arguing that they are atelic achievements

9 that occur instantaneously.

Semelfactives and activities are atelic verbs with no inherent end points. In (30), we observe the reduplication of the activity verb

etuka, “push”. The verb

push has no inherent end point, and it would be difficult to individuate these acts of pushing, considering that there is no change of state in this context. Reduplication with an intensity reading is thus plausible.

| 30. | Context: João tried to enter the house, but the door wouldn’t move. |

| | João-ya | mana’ta | etuka-pî~etuka-pî | | |

| | João-erg | door | push-pst~push-pst | | |

| | João pushed the door vigorously. |

Considering that intensity characterizes unbounded events, it would be logical for these two classes of verbs (semelfactives and activities) to accept reduplication more readily than achievements and accomplishments. This pattern was indeed revealed in our results. In other words, these unbounded events, which are less likely to be able to be counted, make use of reduplication as a measuring strategy.

4.4. A Note on the Syntax of Macuxi Pluractionals

The Macuxi data point to two potential positions where they are generated in the syntax. A syntactic analysis would need to account for several factors: (i) -pîtî being universally acceptable across verbal classes and (ii) the reduplication of semelfactive and activity verbs being more likely than that of achievements and accomplishments.

Scholars have hypothesized that event structure (i.e., thematic and aspectual requirements) is syntactically encoded (

Travis 2010;

Borer 2005;

Ramchand 2008).

Borer (

2005), for instance, posits that Aktionsart is derived via functional structure, considering that verbal roots themselves do not encode aspectual information.

Travis (

2010) posits that Aspect is positioned between two VP shells, and that there are two possible layers for aspectual morphology. Syntactic analyses of pluractionality in various languages have built on these proposals, such as in Mandarin (Sinitic) (

Basciano and Melloni 2017) and Ranmo (Papuan) (

Lee 2016). Ranmo similarly exhibits two strategies for pluractionality (verb alternation and suffixation), and Aktionsart exerts an influence on which verb alternations can give rise to pluractional readings. Lee draws on the framework in

Travis (

2010) to provide a syntactic account, positing a low Aspect head of the feature [+/− bounded] to account for verbal root alternations.

In a similar vein, it might be tempting to presume that Macuxi reduplication occurs lower in the syntax (“Inner Aspect”), due to the telicity constraints. The Macuxi data cited in prior sections demonstrated that innately telic verbs cannot be reduplicated. Crucially, Macuxi verbs must possess the features [+dynamic] and [−telic] to be reduplicated. Conversely, we could posit that the -pîtî morpheme is positioned in the higher AspP in the tree, since it is less sensitive to the [± telic] feature. However, a third factor to account is the co-occurrence of reduplication of a verb suffixed with -pîtî (21), as well as the possible reduplication of the verbal stem and inflectional morphemes (e.g., the tense markers) (22). This might suggest that reduplication perhaps occurs higher in the syntactic tree post-suffixation. We leave a formal syntactic analysis of these two pluractional strategies for future work.

5. Macuxi and Beyond: Pluractionality in the Cariban Family

In the previous sections, we observed how multiple events are encoded in Macuxi through the -pîtî morpheme, while reduplication tends to be associated with the intensity of an action, and less with a multiplicity of events. These strategies in fact share similarities with pluractional strategies found in other languages in the Cariban family.

We conclude by discussing how the cognates of -

pîtî surface in other Cariban languages. This construction has been described as the most widespread pluractional strategy across the Cariban family. Focusing on the Akawaio -

pödï morpheme,

Mattiola (

2019) describes it as sharing the same semantic functions as similar morphemes that occur in other Cariban languages, including Macuxi, Carib and Panare. These suffixes are cognates that may share the same diachronic origin.

Mattiola (

2019) discusses these cognates of *-

pëtï, drawing a connection to at least the Venezuelan branch of the Cariban family, summarized in

Table 6.

The functions of these morphemes across these languages appear to overlap across different branches. In Carib (Guianan), the suffix -

poty has been described as encoding iterativity, frequentativity (31), habituality and spatial distributivity (32) (

Courtz 2008, p. 82;

Mattiola 2019, p. 107). This also surfaces in Ye’kwana as -

jötï, and shares similar functions of iterativity and frequentativity (

Cáceres 2011).

| 31. | y-(w)yto-ry | ta | y-jámun | ky-ni-ase-tyka-poty-jan-no | wara |

| | 1-go-possc | in | 1-body | alleg-aeo-rxc-shock-iter-prsu-adn | like |

| | “As I went, my body seemed to shiver continually, as it were.” |

| | |

| 32. | w-(w)yto-poty-ja | te | pàporo | moro-kon | pakira |

| | IM-go-iter-prs | but | all | that-pl | collared-peccary |

| | | ase-kupi-tòkon | warano |

| | | rxc-bathe-nipl | at_every_instance_of |

| | “But I went to all the places where peccaries bathe.” |

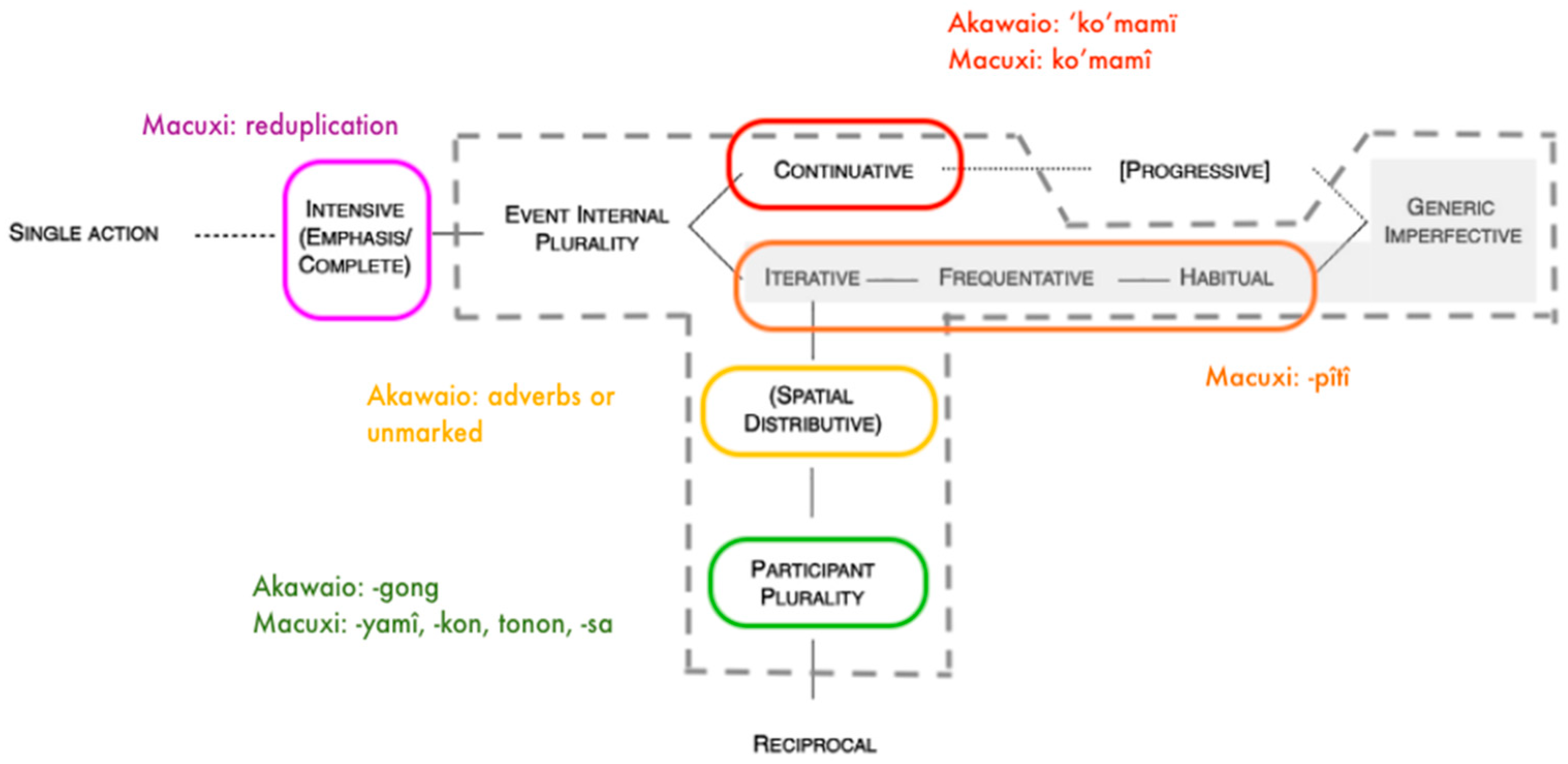

In his typological study, Mattiola proposes a conceptual space of pluractionality, which we have adapted for Macuxi in

Figure 1 (based on a case study on Akawaio). In Mattiola’s map, the functions on the left side are likely to be constructions that (a) are not grammaticalized, (b) fall farther out from the core functions of pluractionality and (c) rely heavily on

Aktionsart. The -

pîtî morpheme and its associated core functions, as discussed in previous sections, are circled in orange in the center of the conceptual map. We also include the other constructions encoding different pluractional functions, using red for the continuative and green for participant plurality functions. While there is no mention or discussion of the interpretation of intensity in the other Cariban languages in Mattiola’s typology, the intensity function of reduplication in Macuxi may be placed on the left side of the conceptual map (in purple). Mattiola’s placement of intensity as a secondary function, external to the core pluractional functions of event plurality (e.g., iterativity), is parallel to the treatment of intensification as a “special”, additional meaning in

Součková (

2011), which we adopted in this paper.

6. Concluding Remarks

The present study explored the form and functions of two constructions in Macuxi: the -pîtî morpheme and reduplication. The distribution and interpretation of these two constructions suggest that while -pîtî is specifically able to encode multiple, individuable events, reduplication is primarily associated with a dimension of measurement other than cardinality: intensity.

Through the analysis of data from context-based elicitations, our findings suggest that -

pîtî is a main, grammaticalized, pluractional strategy, applicable to verbs across the different

Aktionsarten. We confirmed that the functions of the -

pîtî morpheme allow the distribution of events over a period of time. Crucially, while this morpheme has been described in the literature as only encoding habitual events when it co-occurs with the past tense -

pî (

Abbott 1991), we found that non-habitual, multiple events are also compatible with their co-occurrence. In addition, we argued that these functions of the -

pîtî morpheme can be predicted with

Lasersohn’s (

1995) proposal with respect to the distribution of events over time. Based on this analysis, it is possible to predict both habitual and non-habitual multiple events, distributed over time. We also showed that the form and function of the Macuxi -

pîtî mirrors that of a cognate, -

pödï, in Akawaio, a neighboring Cariban language, as discussed in

Section 5.

Regarding reduplication, we showed that this phenomenon is associated with a secondary function (i.e., intensification), which is influenced by

Aktionsart: semelfactive and activity verbs tend to be reduplicated, while achievements and accomplishments are less likely to accept reduplication. In

Section 4, we showed how

Lasersohn’s (

1995) formalization is inadequate in accounting for the function of the intensity associated with reduplicated verbs. We adopt an approach from

Součková (

2011) in treating Macuxi’s two strategies of pluractionality as two semi-independent components. Reduplication and its associated “special” intensification function should be treated differently, especially considering its limitations, based on

Aktionsart. Considering that atelic verbs, such as activities and semelfactives, were more likely to be reduplicated, we can associate this with the notion that these verbs denote actions that are not as easily individuable as telic events. Rather than being associated with a cardinality of events or

counting events, reduplication can be said to be associated with

measuring events instead, based on a different dimension, such as intensity. Similarly, intensity is classified as a secondary, additional function of pluractionality in

Mattiola’s (

2019, p. 36) typology, defined as one that encodes “a situation done with more effort or whose result is augmented with respect to the normal happening of the same situation”. Therefore, we suggested that reduplication and this intensity function in Macuxi could potentially be placed on the left side of Mattiola’s semantic map, which is also associated with a reliance on

Aktionsart.

In sum, this paper provides an analysis of different strategies for counting a multiplicity of events (via the -pîtî suffix) and measuring events (via reduplication) by reconciling formal analyses of pluractionality, Aktionsart and conceptual maps.