2. Background

Lenition has been described as movement towards deletion, or increased sonority; that is, the degree of openness of a particular segment, either vocalic or consonantal, decrease in articulatory effort as well as modifications to articulatory gestural patterns (

Lavoie 2001). Vowels and consonants are ranked in order of their openness on a sonority scale from weakest consonantality (i.e., least obstruction of airflow), to strongest consonantality (i.e., most obstruction of airflow); that is, most open or vowel-like to most closed or consonant-like (see

Table 1 from

Hualde (

2005, p. 72)).

The consonants within this sonority scale are also ranked according to their openness, or degree of constriction.

Lass (

1984) offers two hierarchical consonant scales (see 1), where movement toward the right on both hierarchies indicates lenition, or consonant weakening, and movement toward the left indicates fortition, or consonant strengthening. The hierarchy in (1a) represents a scale of openness, where rightward movement along the scale equals less resistance to airflow within the vocal tract.

Hualde (

2005, p. 300) defines a stop as a “consonant produced with total occlusion in the oral cavity,” not allowing the passage of air such as /ptkbdɡ/. Fricatives are “consonants produced with a narrowing of the articulatory channel, resulting in turbulence or noise,” such as /fθsʃxh/, while an approximant is a production where the articulatory organs in the oral cavity approach each other, but do not touch and do not have enough constriction to produce friction, thus differing from a fricative production (

Hualde 2005, pp. 295, 297). Examples of approximants in Spanish include the allophones of /bdɡ/, [βðɣ], as well as [j] and [w] in lexical items with <ie> and <ue> combinations, where the articulatory organs approach each other, allowing some constriction but no contact. Zero represents total deletion of the consonant. The hierarchy in (1b) represents a sonority scale, where rightward movement along the scale equals higher output of periodic acoustic energy, which serves as a cue to decreased obstruction of airflow (

Lass 1984). Voiceless productions do not include vibration of the glottal folds, whereas voiced segments are produced with glottal fold vibration.

| (1) | a. | Stop → Fricative → Approximant → Zero |

| | b. | Voiceless → Voiced |

While the scales in (1) may not be appropriate for other consonant segments, such as affricates, they inform the primary purpose of the current study by describing occlusive consonants with respect to their level of sonority as well as degree of constriction. This study explores the extent to which occlusive consonants assimilate in vocalic quality to their adjacent vowels (i.e., the degree of consonant lenition) and other linguistic variables that evidence weakening phenomena. These variables are discussed in the following subsections.

2.1. Lenition and Lexical Stress

Lexical stress is an important factor in consonant lenition, concretely expressed through the phonetic correlates of fundamental frequency (f0; the perception of f0 is pitch), duration and/or intensity (

Hualde 2005). While a higher f0 does not necessarily indicate a stressed syllable, an f0 rise through a stressed syllable is often essential in identifying possible cues to stress rather than other types of f0 movement or f0 peaks (

Hualde 2005). Duration is also a relevant phonetic correlate to the discussion on lexical stress, given that stressed syllables generally have a longer duration than unstressed syllables. The third expression of lexical stress is intensity, which is one of the phonetic correlates of particular interest to the current study. With respect to consonant lenition, measuring relative intensity (RI) or the difference in decibels (dB) between the intensity of a consonant and the intensity of the following vowel informs the notion of relative prominence effects by providing the degree of occlusion or openness of a particular segment. Stressed syllables, therefore, use increased articulatory energy and gestures, which are manifested through enhanced f0, duration and/or intensity. These three correlates enhance the prominence of lexical stress, ultimately working against the weakening processes of lenition because more prominent syllables experience less consonant weakening than unstressed syllables (

Browman and Goldstein 1992;

Cho et al. 2006;

Gili Fivela et al. 2008;

Keating et al. 2003).

2.2. Lenition and Prosodic Position

At the beginning of domains, such as syllable onset or the beginning of a prosodic word, there is strengthening, but not at the end of a domain. In a study about prosodic boundaries in two varieties of Italian,

Gili Fivela et al. (

2008) found domain initial strengthening in the production of consonants in an initial position, that is, at the beginning of an intonational phrase as well as in smaller domains, such as the intermediate phrase.

Cho et al. (

2006) investigated word-initial strengthening of native speakers of American English, concluding that there are acoustic differences between consonants in word-initial position and those in word-internal position, indicating strong evidence for word-initial consonant strengthening. In a cross-linguistic investigation between English, French, Korean, and Taiwanese to compare and determine the effects of word-initial strengthening,

Keating et al. (

2003) identify clear distinctions between the initial position and internal position in each of the four languages.

Intervocalic position, or VCV, is among those at the top of the list of favorable environments for lenition processes to occur (

Lass 1984), given the sonorous quality of adjacent vowels and the assimilation processes that promote increased sonority of occlusive consonants when found in this position. While word-final is also a likely position in which to find consonant weakening, the current study will only focus on word-initial consonants preceded by a vowel. Given the research on domain initial strengthening, consonants in word-initial intervocalic position are expected to be more highly occluded than those in word-internal intervocalic position. These studies demonstrate the need to investigate not only phonological correlates like lexical stress and flanking vowels, but also word position. In prosodically strong positions such as word-initial as well as in stressed syllables, the articulatory gestures are reinforced in many languages, indicating a cross-linguistic phenomenon not limited to Spanish.

2.3. Lenition of Stop Consonants in Spanish

2.3.1. Lenition of /ptk/

Previous studies show that sonorization of voiceless occlusives is attested in the spontaneous speech of many varieties of Spanish, including Canary Islands Spanish, Andalusian Spanish, and the Spanish of Mallorca in the Balearic Islands (

Hualde et al. 2011;

Oftedal 1985;

O’Neill 2010;

Trujillo 1980). This phenomenon appears gradient in nature, rather than binary, with higher and lesser degrees of weakening occurring along a lenition continuum, varying according to context and sociolinguistic factors (

Colantoni and Marinescu 2010;

Lewis 2001;

Oftedal 1985;

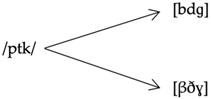

Trujillo 1980). According to these studies, in addition to the traditional voiceless realization, underlying /ptk/ can be realized phonetically as completely or partially voiced as well as approximant (see 2).

| (2) | ![Languages 08 00224 i001]() |

Comparative studies on voiceless stop consonant lenition conclude that some Spanish varieties exhibit higher degrees of consonant weakening than others. For example, in

Lewis (

2001), a Northern Spanish dialect appeared to be at a more advanced state of change with respect to consonant lenition than a Central Colombian dialect, further suggesting a lenition continuum from weak to strong.

O’Neill (

2010) concluded that in Andalusian Spanish, most voiceless occlusive segments in intervocalic position are realized as voiced segments, and in turn, the underlying voiced segments can result in loss. In the Spanish of Mallorca,

Hualde et al. (

2011) found that one-third of underlying voiceless occlusives in intervocalic position experience complete, or at least partial, voicing of /ptk/ in semi-spontaneous speech. Relative intensity differences are higher for voiceless segments than for voiced segments, an expected finding; however, the authors also conclude that the degree of lenition varies according to point of articulation. Velar segments are more sonorous than coronals, which in turn are more sonorous than labials. Important to note in the work of

Hualde et al. (

2011) is that despite the voiced realizations of underlying /ptk/, this does not indicate merger of phonemes /ptk/ with /bdɡ/, given that the realizations of these phoneme series differ with respect to their degree of constriction.

2.3.2. Lenition of /bdɡ/

Scholarly work on voiced stop consonant production in Spanish shows great variability in the degree of constriction according to factors such as prosodic position and flanking vowels as well as dialectal variation. In a review of Castilian Spanish,

Cole et al. (

1999) found significant variation in lenition of /ɡ/ according to prosodic position and flanking vowels. Their study concludes that /ɡ/ exhibits the greatest degree of weakening following a stressed vowel or with flanking vowels /o/ and /u/. Weakening is not as prominent, however, when /ɡ/ precedes a stressed vowel or flanking vowels /i/, /e/, and /a/. Results indicate that /ɡ/ has a more complete closure when flanked by /a/ instead of more closed vowels /u/ or /i/. Work completed by

Ortega-Llebaria (

2004) on Caribbean Spanish draws similar conclusions; /ɡ/ is more lenited with flanking vowels /i/ and /u/, but less lenited with flanking vowel /a/. Other studies such as

Lewis (

2001) and

Kirchner (

2004), however, determined that more open vowels favor weakening. Possible explanations of the differences across studies could include speaker demographic as well as task type. Participants from

Lewis (

2001) from Northern Spain and Central Colombia performed three tasks: semi-spontaneous conversation, textual reading, and reading of a word list; participants from

Cole et al. (

1999) were all from Spain and produced words set within a carrier phrase; and participants from

Ortega-Llebaria (

2004) were speakers of Caribbean Spanish and produced nonce words in the form of a game with cartoon characters. All these studies have very different participants as well as speech tasks; therefore, the diverse methodologies employed in these studies could be a contributing factor to the mixed results with respect to the effect of flanking vowels on consonant lenition.

Concerning prosodic position,

Eddington (

2011) concluded that /β/ and /ð/ favor a more occluded production following stressed syllables, in contrast with /ɣ/,

1 which does not conform to the same pattern, exhibiting lower degrees of weakening between two stressed syllables. Also, word frequency affects /ð/ with higher degrees of weakening in high frequency words, but not /β/ or /ɣ/. The segment /ð/ also lenites more frequently in the past participle suffix -ado. Based on

Eddington (

2011), it is clear that /βðɣ/ alternations do not operate uniformly with respect to phonetic context, stress, word frequency, or suffix appearance. The current study investigates precisely this claim made by

Eddington (

2011), by examining the production of occlusive stop consonants through a gradient lens, with the understanding that segments may yield varied productions across different varieties of Spanish with respect to the different acoustic and extralinguistic variables studied.

Carrasco et al. (

2012) compared allophonic patters of /bdɡ/ in Costa Rican Spanish and Madrid Spanish. The results determined that the Spanish of Costa Rica has a different allophonic distribution than that of Madrid, with more closed or open variants of /bdɡ/ according to position, whereas the allophones in the Madrid variety do clearly separate allophones in different positions. The allophones in Costa Rican Spanish are weaker in internal position as compared to initial position, and RI measures present higher values in stressed syllables. The authors connected these two varieties by saying that Costa Rican Spanish represents an earlier stage of weakening than the more extensive weakening found in the Madrid variety, much like the comparison made by

Lewis (

2001) between Central Colombian and Northern Spanish dialects.

2.3.3. Lenition of /ptk/ vs. /bdɡ/

Due to the inherent voiced and voiceless nature of /bdɡ/ and /ptk/, respectively, few studies have compared these two series with each other to investigate the gradient nature of lenition and the interplay of linguistic and extralinguistic factors such as point of articulation, lexical stress, flanking vowels or dialect.

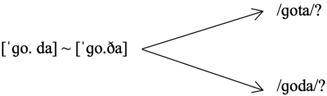

Martínez Celdrán (

2009) investigated potential confusion of minimal pairs between intervocalic voiceless and voiced segments produced by a Murcian speaker. According to the author, variant realizations of the intervocalic occlusive segment can lead to possible confusion of the underlying phoneme (see 3).

| (3) | ![Languages 08 00224 i002]() |

In a perceptual test used to determine to what extent speakers have difficulty identifying the underlying segment, the participants from Barcelona in

Martínez Celdrán (

2009) interpreted most of the proposed voicings––both underlyingly voiced and voiceless––as voiced in 92.5% of cases. That is, participants taking the perceptual test identified ‘bozo’ instead of the correct ‘pozo’. Participants completing the same perceptual test from Murcia, however, did not reach the same level of voicing identification, identifying the segments as voiced in only 69.48% of cases. Results of the perceptual test determined that participants favor the voiced variant when selecting among isolated words, but that confusion disappears when the words appear in context. Therefore,

Martínez Celdrán (

2009) concluded that due to the neutralization of voicing, tension, and duration of the segments, context is what allows the correct interpretation of consonant segments in intervocalic position.

In Argentine Spanish,

Colantoni and Marinescu (

2010) determined that there is not a correlation between weakening of intervocalic voiceless segments and intervocalic voiced segments. The results do not indicate clear evidence in favor of any voiceless occlusive weakening in intervocalic position in Argentine Spanish. However, the authors noted that when surface lenition of voiceless occlusives /ptk/ is observed, labial segments appear to demonstrate more lenition than coronal and velar segments, contrary to other studies that find the highest degree of lenition among velar segments (e.g.,

Hualde et al. 2011). When the authors observed lenition of voiced segments /bdɡ/, however, coronals are produced with more weakening than labials and velars, which is inconsistent with

Hualde et al. (

2011), but consistent with the results from

Lavoie (

2001).

Colantoni and Marinescu (

2010) also consider the effect of flanking vowels on the degree of weakening in Argentine Spanish, but their hypothesis that weakening would increase when the consonant segment is surrounded by more open vowels is only partially confirmed.

Previous work reviewed in this section determines that allophones of /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ are gradient in nature and vary according to language variety and other linguistic factors, with some exhibiting more weakening, such as the higher degrees of stop consonant lenition found in peninsular varieties of Spanish as compared to Latin American varieties of Spanish. As shown in the previous work in this section underlyingly voiceless /ptk/ often surface as completely or partially voiced allophones [bdɡ]. Differing degrees of weakening are present with respect to point of articulation, in which velar segments are most lenited as compared with coronals and labials. These studies suggest that stop consonant lenition is not a binary phenomenon (i.e., voiced vs. voiceless), but instead more gradient in nature, where different Spanish varieties experience more or less consonant weakening according to various linguistic and extralinguistic factors. These studies inform the existing knowledge on the production of voiced stop consonants and motivate the current study by offering conclusions with respect to the variables that affect consonant lenition and demonstrate the variability that appears in stop consonant production in Spanish.

2.4. Lenition and Relative Intensity

As reviewed in the previous section, phonetic realizations of /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ vary with respect to their degree of intensity across varieties of the same language as well as cross-linguistically, with realizations ranging from weak approximant to fully occluded stop, including voicing and even spirantization of the voiceless occlusive series. The acoustic variable of RI may provide evidence of consonant lenition, representing the difference in dB between the segment in question and the following vowel. This is measured by identifying the minimum intensity of the target segment using the intensity curve in Praat (

Boersma and Weenink 2013), as well as the maximum intensity of the following vowel and taking the difference. The minimum pitch value set for data analysis in Praat was 75 Hz (see

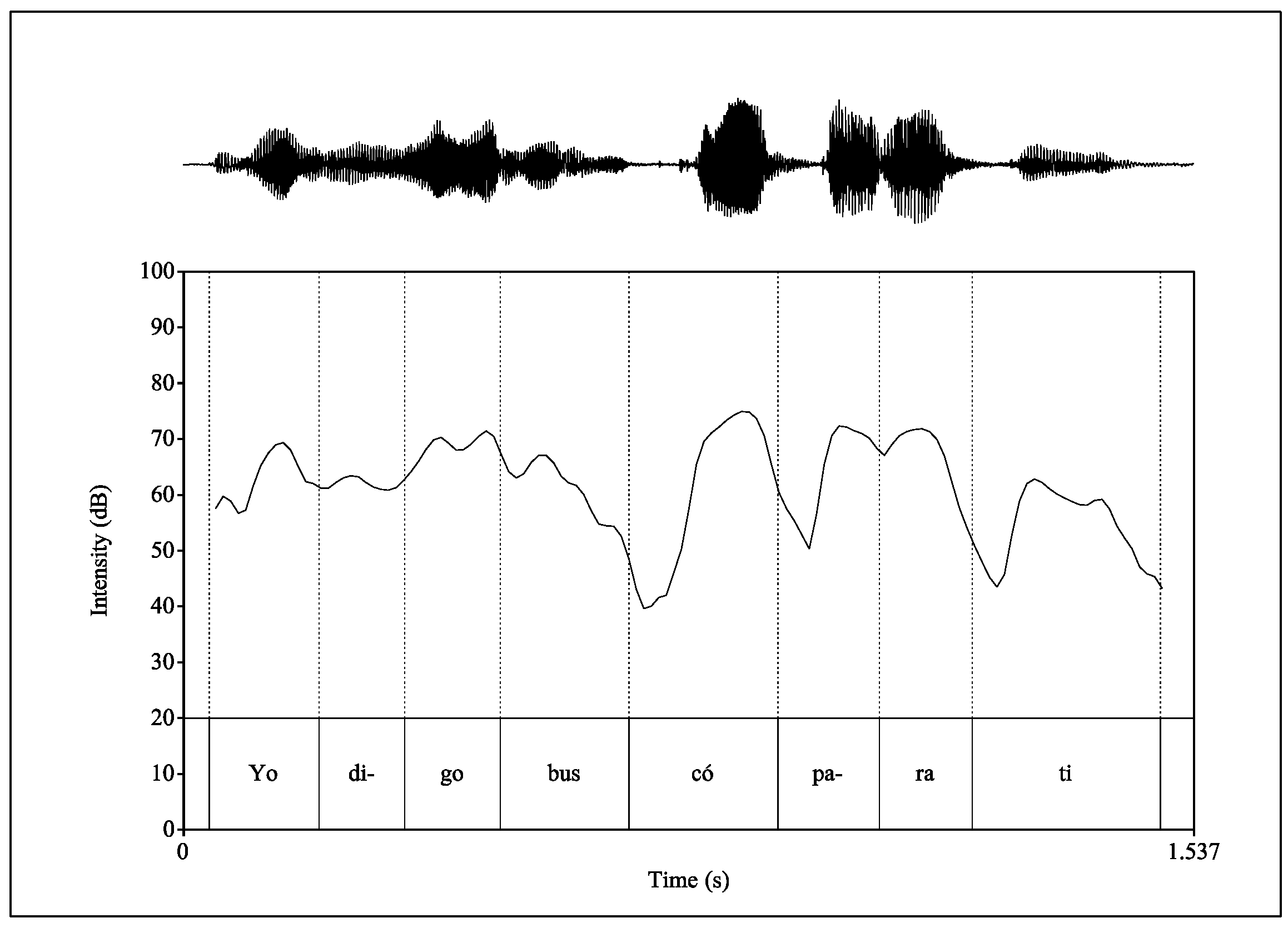

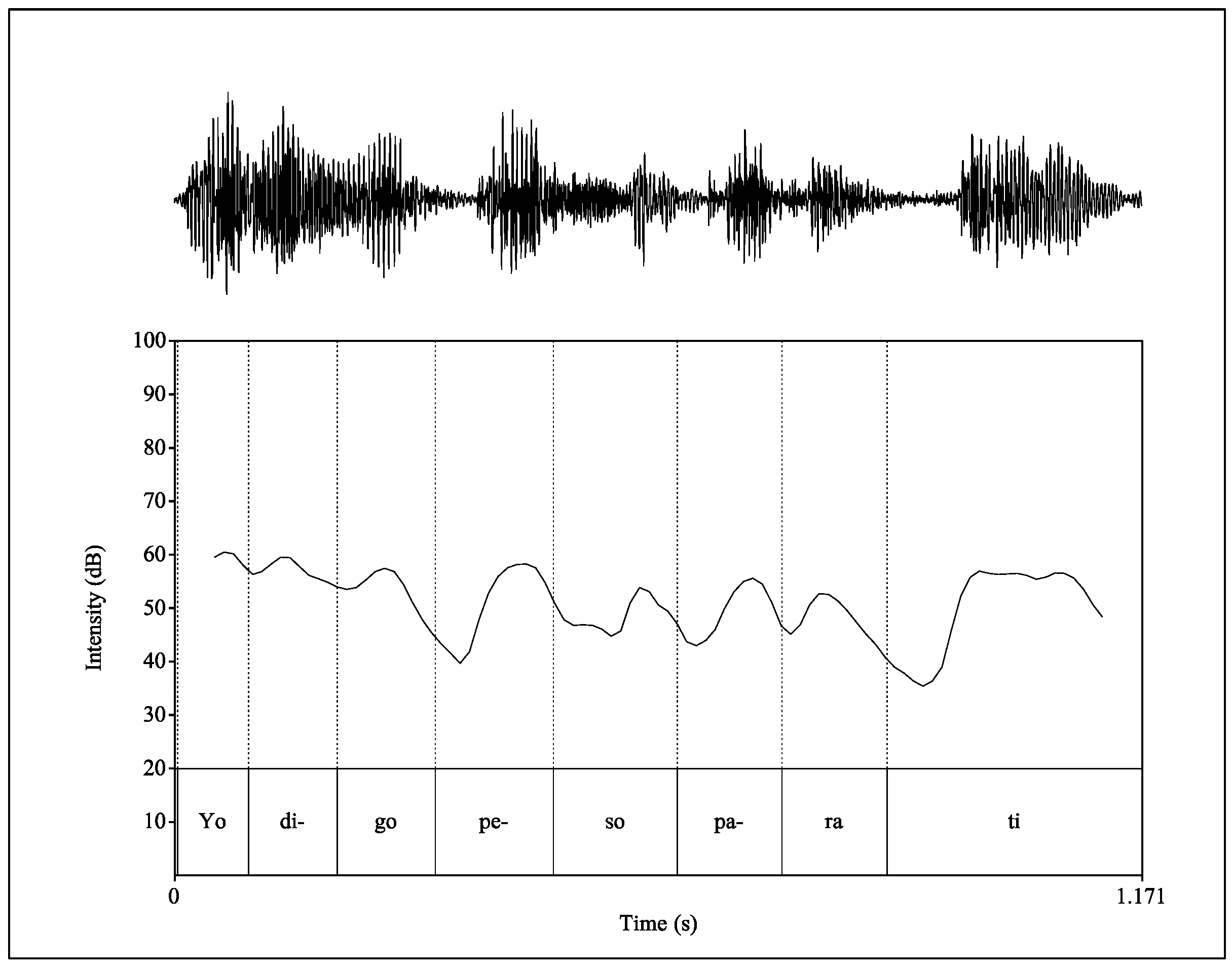

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

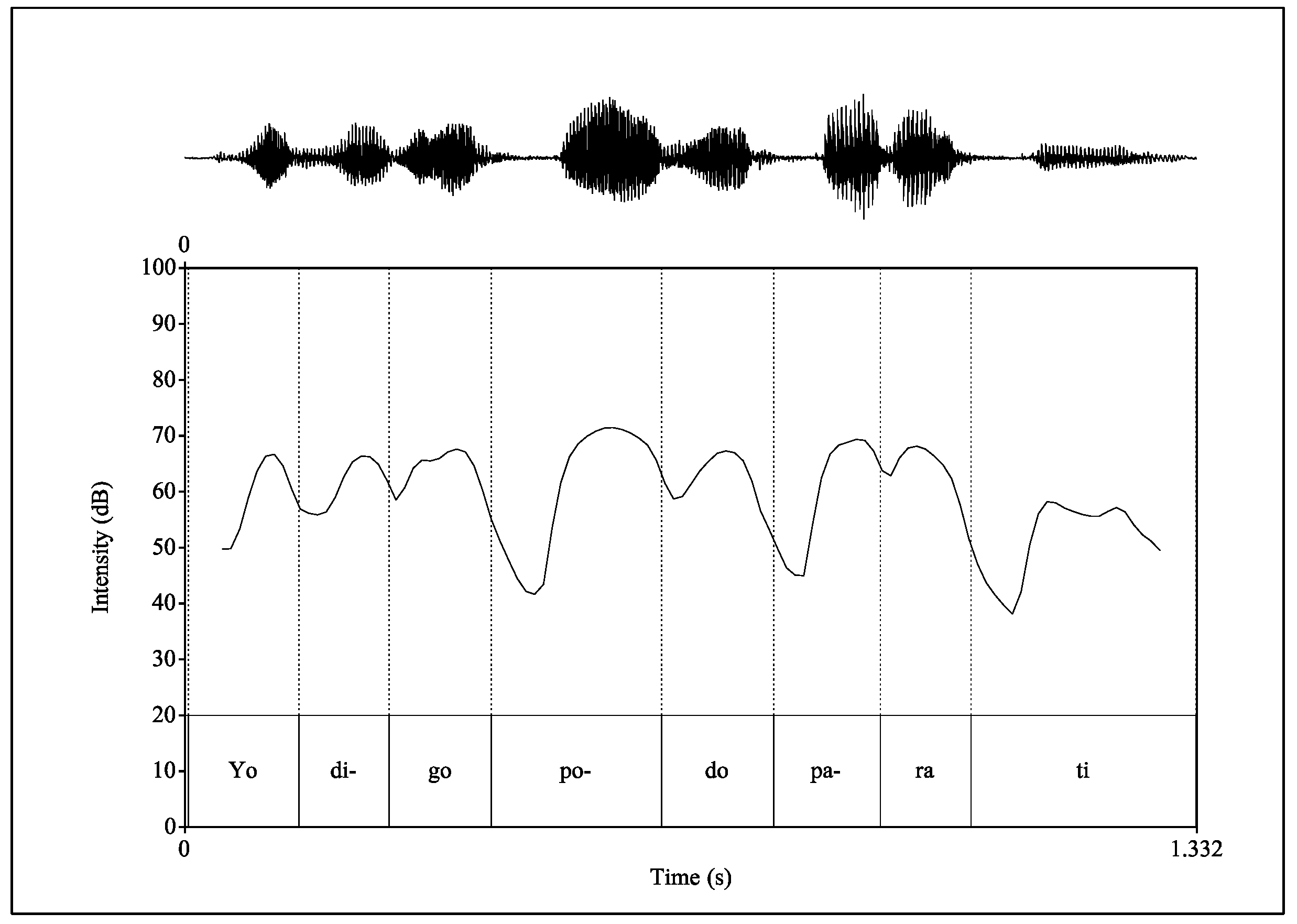

Figure 3 for the Praat spectrogram and intensity curve of Spanish utterances that include voiceless and voiced consonant productions).

Figure 1 represents Yo digo podo para ti (‘I say I prune for you’). Within the boundaries of the syllable po- in

Figure 1, the minimum intensity value of [p] is 40.9 dB, and the maximum intensity value of the following vowel [o] is 71.4 dB. The RI difference, then, between the valley and peak is 30.5 dB.

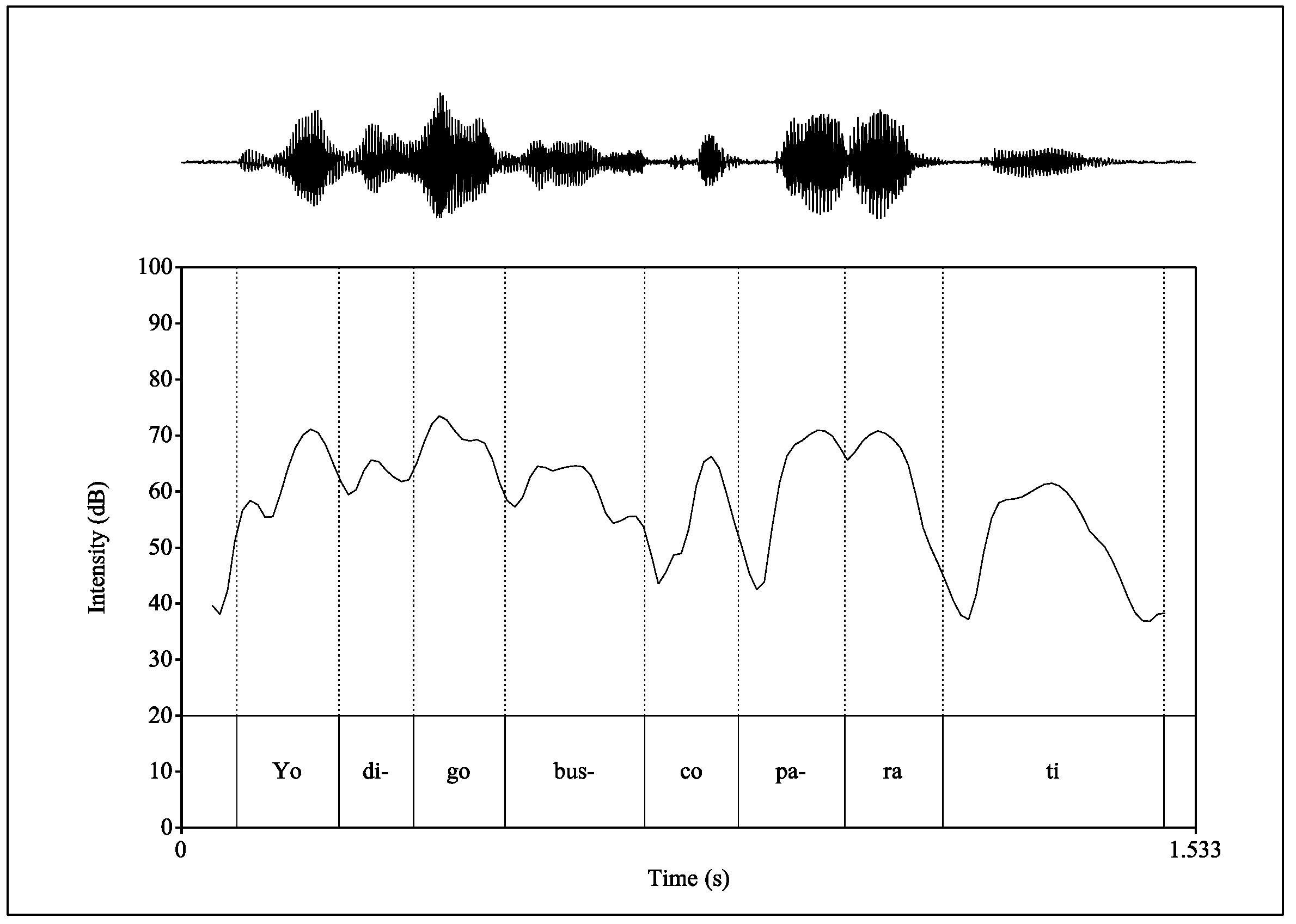

Figure 2 includes the spectrogram and intensity curve for the utterance Yo digo busco para ti (‘I say I look for for you’). Within the boundaries of the syllabus bus- in

Figure 2, the minimum intensity value of [b] is 57.1 dB, and the maximum intensity value of the following vowel [u] is 64.6 dB, yielding a RI difference of 7.5 dB. The lower RI value of this consonant [b] indicates a more open production than the [p] analyzed in

Figure 1.

Figure 3 represents Yo digo buscó para ti (‘I say he looked for for you)’ with an even lower RI measurement; thus, a more open, vowel-like production of the consonant [b]. Within the boundaries of the syllabus bus- in

Figure 3, the minimum intensity value of [b] is 63.0 dB, and the maximum intensity value of the following vowel [u] is 67.2 dB, with a RI difference between the valley and peak of 4.2 dB. A lower RI measurement indicates a high degree of weakening in intervocalic position. Comparing the production of [b] in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, there is a difference in the consonant valleys and the vowel peaks. One contributing factor to this difference is lexical stress; that is, busco ‘I look for’ in

Figure 2 is a paroxytone word, where the first syllable bus- carries lexical stress and is therefore more prominent, with less consonant weakening, while buscó ‘he looked for’ in

Figure 3 is an oxytone word and carries lexical stress on -có, leaving the first syllable bus- less prominent, and therefore with more consonant weakening.

Given the inherent nature of both occlusive series, RI can be used to compare voiceless segments to their voiced counterparts, a task that is difficult to achieve with other acoustic variables such as voice onset time or percent voicing. In intervocalic position in Spanish, higher RI measurements of phonemes /ptk/ and lower RI measurements of phonemes /bdɡ/ are expected. RI can be used to provide evidence of consonant lenition and weakening by acoustically quantifying the degree of occlusion and the manner of articulation of consonant production. The current study examines the gradient nature of these lenition processes in Spanish in order to situate the occlusive consonants /bdɡ/ and /ptk/ on a lenition continuum from weak to strong and to determine the acoustic variability that exists among these segments in different Spanish varieties.

2.5. Motivations and Research Questions

From the above review of recent work on stop consonant weakening, many studies focus on either voiced stops /bdɡ/ or voiceless stops /ptk/ and only analyze one or two Spanish varieties at a time for side-by-side comparison, rendering difficult a complete synchronic analysis of stop consonant lenition across the Spanish-speaking world. These studies, therefore, motivate the current study to explore the degree of consonant weakening for both /bdɡ/ and /ptk/ and the potential degree of overlap between the phonetic realizations of these phonemes by determining the extent of allophonic variability in the speech of multiple Spanish varieties when controlling for variables such as point of articulation, lexical stress, flanking vowels, and speech variety.

For this study, data were collected from a sample set of native Spanish speakers from six different regions to create a varied native speaker pool to compare stop consonant production and variation between different varieties, including Peninsular varieties of Spanish as well as Latin American varieties (Colombian, Chilean, and Mexican Spanish). Peninsular varieties tend to exhibit more open consonant realizations, that is, higher degrees of weakening, while Latin American varieties have previously yielded more occluded consonant productions, that is, lesser degrees of weakening (

Carrasco et al. 2012;

Lewis 2001). The varieties represented are grouped primarily according to country, except for Spain, which is divided into two groups based on like phonetic characterizations (

Hualde 2005): North-Central Peninsular varieties and Southern and Insular Peninsular varieties. The former includes participants from cities such as Ponferrada, Lugo, Valladolid, Salamanca, and Madrid, while the latter includes two southern Peninsular cities, Granada and Malaga, as well as two insular varieties from Grand Canary Island and Mallorca. The southern Peninsular cities are grouped together with the insular varieties since previous research shows that speakers from these regions exhibit higher degrees of weakening than those from North-Central Spain (c.f.

Lewis 2001 for a Northern Peninsular variety,

Hualde et al. 2011 and

Oftedal 1985 for Insular varieties—Balearic and Canary Islands, respectively—and

O’Neill 2010 for Andalusian Spanish). Although the geographic distribution of the Spanish varieties included is by no means exhaustive, the cities included offer a geographic range of different varieties across the Spanish-speaking world.

The research summarized here motivates the current study by highlighting main findings on the topic of stop consonant weakening in Spanish and identifying areas for continued exploration of acoustic variability. The research questions are the following: (1) how does consonant lenition of voiced /ptk/ and voiced /bdɡ/ vary according to linguistic factors such as point of articulation, lexical stress, and following vowel in different Spanish varieties? and (2) does consonant lenition depend on Spanish variety, and if this is the case, which varieties exhibit higher and lower degrees of stop consonant weakening? This research will explore variability in the degree of weakening across and among different Spanish varieties using RI measurements for voiced /bdɡ/ and voiceless /ptk/. In analyzing data from these geographical areas and controlling for the linguistic variables, the goal of this study is to initiate a review of synchronic consonant lenition of both voiceless occlusives as well as voiced occlusives of multiple Spanish varieties to explore existing research gaps in stop consonant variability across the Spanish-speaking world.

5. Discussion

The results presented in the previous section detail gradient variation in the degree of consonant occlusion according to the geographical location of the Spanish varieties analyzed depending on various linguistic factors. This section discusses the results within the context of the research questions, repeated here: (1) how does consonant lenition of voiced /ptk/ and voiced /bdɡ/ vary according to linguistic factors such as point of articulation, sonority, lexical stress, and following vowel in different Spanish varieties? and (2) does consonant lenition depend on Spanish variety, and if this is the case, which varieties exhibit higher and lower degrees of stop consonant weakening? Key points are summarized in

Table 9.

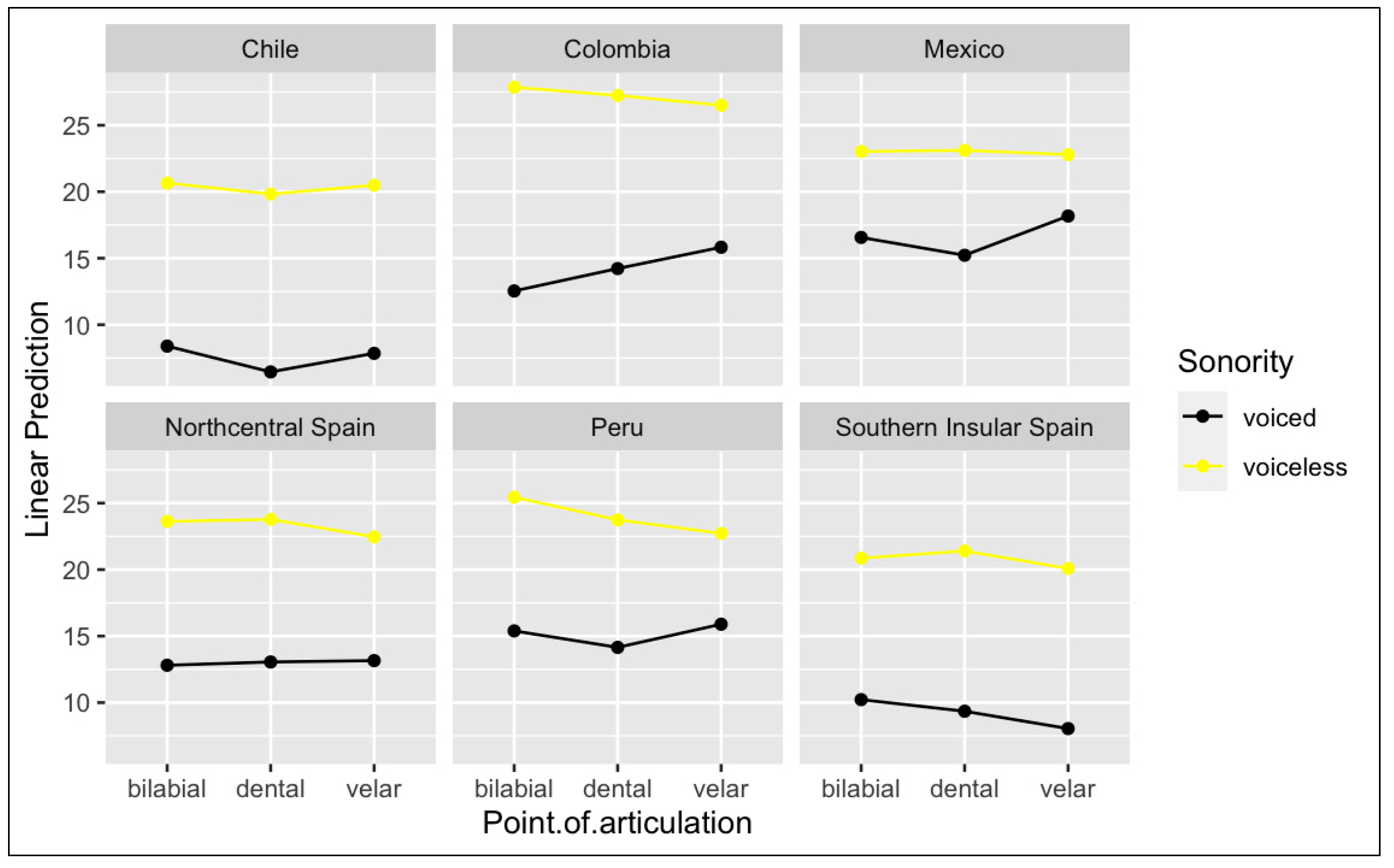

Previous research suggests that velar segments would produce higher degrees of weakening when compared with labial and dental segments; this is only partially confirmed by the results of this study.

Lewis (

2001, p. 160) states that “[t]he influence of place of articulation on RI differences was not statistically significant” which is consistent with the statistical modeling from the current data set. When considering the interaction of both point of articulation and region on RI, however, the results are indeed significant, meaning that speakers from different regions exhibit differing degrees of weakening according to point of articulation. Given that

Lewis (

2001) includes data from one Peninsular variety and one Latin American variety to measure relative intensity differences, these results show promise for future research on differences in point of articulation according to region.

Colantoni and Marinescu (

2010) found the highest degree of lenition for dental stops in Argentine Spanish; this is also the case for dental stops for Chilean Spanish speakers in the current study; geographical proximity here could play a role in why point of articulation differs for Chilean speakers compared with those from the other speaker groups.

Carrasco et al. (

2012) find that voiced velar /ɡ/ is more lenited than bilabial /b/ and dental /d/ in postconsonantal position, but not in post-vocalic position where /ɡ/ is stronger. Given that the task items for the current study include only those in post-vocalic position, the findings confirm that /ɡ/ is more occluded than /b/ and /d/ and not only in North-Central Peninsular speakers, but also for Colombian, Peruvian, and Mexican speakers. The results here show that the voiced velar segment is stronger than the voiced bilabial and voiced dental, but that this does depend on region. Findings from the current analysis of point of articulation on relative intensity shows that region is also a significant factor in the equation and should be taken into account when reporting on stop consonant lenition variation.

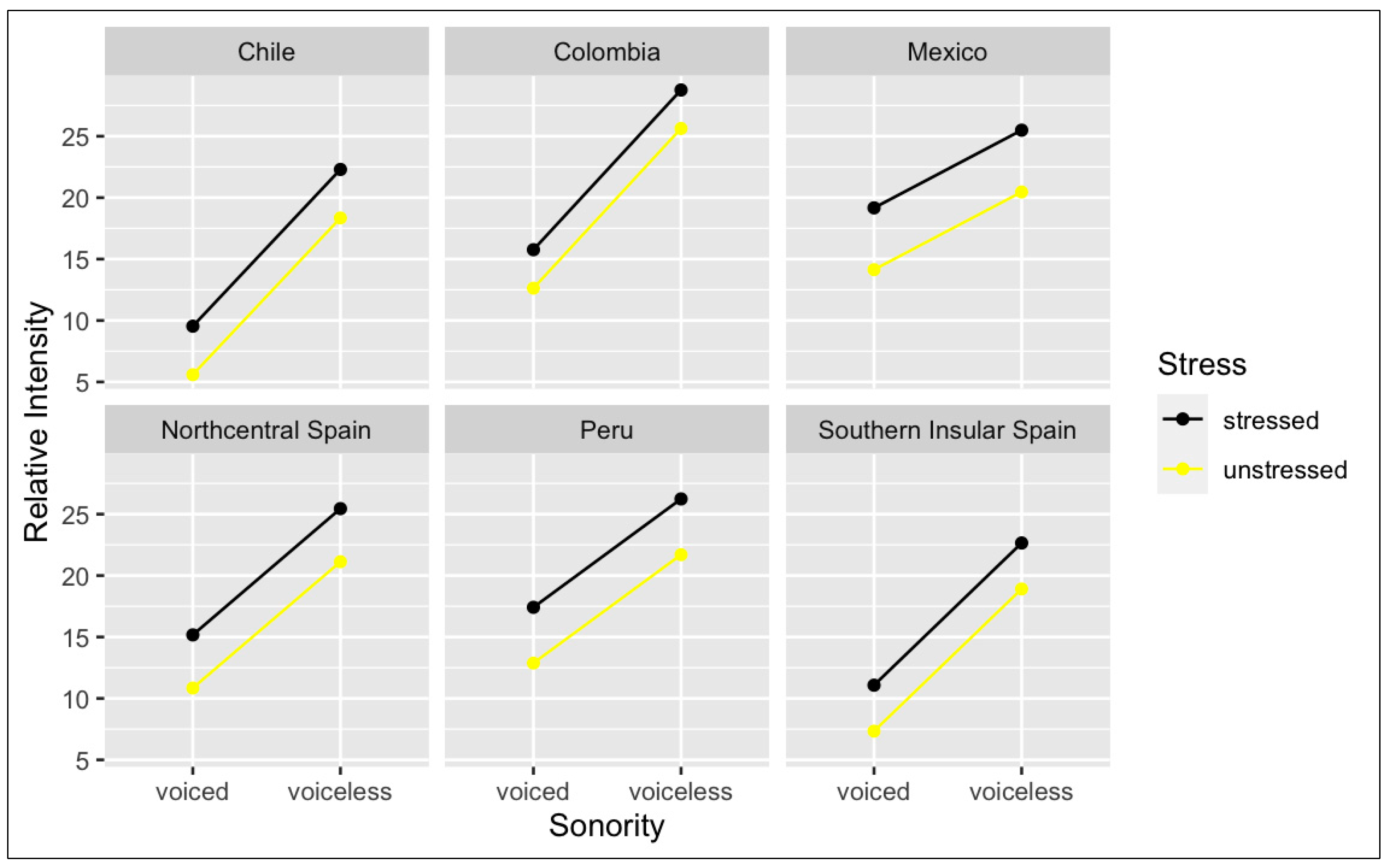

In agreement with previous research on consonant lenition, results confirm that stop consonant productions are more lenited when followed by a lexically unstressed syllable as opposed to a lexically stressed syllable (

Browman and Goldstein 1992;

Cho et al. 2006;

Gili Fivela et al. 2008;

Keating et al. 2003). This is to be expected, confirming that higher degrees of weakening occur in unstressed syllables when compared to their stressed counterparts; however, the effect of lexical stress on RI does not interact with region. All data points were collected from word initial position; although still intervocalic within the carrier phrase, this is a prosodically strong position, and consonant weakening still occurs, perhaps albeit to a lesser degree. Although previous work tells us that consonant lenition in Spanish occurs both within words and across word boundaries, higher degrees of lenition are expected in word internal position as compared to word initial position. While the mixed effects model does produce a main effect for vowel horizontal and vertical positions; these variables do not interact with region, meaning that speakers from different regions do not produce more/less consonant weakening than those from other regions. The results for the current study are consistent with those found in

Ortega-Llebaria (

2004) where more lenition is found with high vowels /i/ and /u/ and less lenition with the low and mid vowel /a/, but contrast with those found in

Lewis (

2001) and

Kirchner (

2004), where mid and low vowels favor weakening, indicating a need for more data regarding the overall effects of flanking vowels on consonant lenition. Variables that could have impacted the results of the vowel analysis are task type. For example, data from

Lewis (

2001) include both spontaneous speech as well as a textual reading, a word list, and a short phrase list. Participants in

Ortega-Llebaria (

2004)’s study were asked to remember names of made-up cartoon characters; both of these studies use very different task types from the current study. It is noteworthy, however, that this study only analyzed the results of the following vowel on consonant production, keeping constant the preceding vowel as part of the carrier phrase, Yo digo ____ para ti ‘I say ____ for you’. The preceding vowel in all cases was /o/. Further research should explore both flanking vowels for potential effects on the degree of consonant weakening according to Spanish variety.

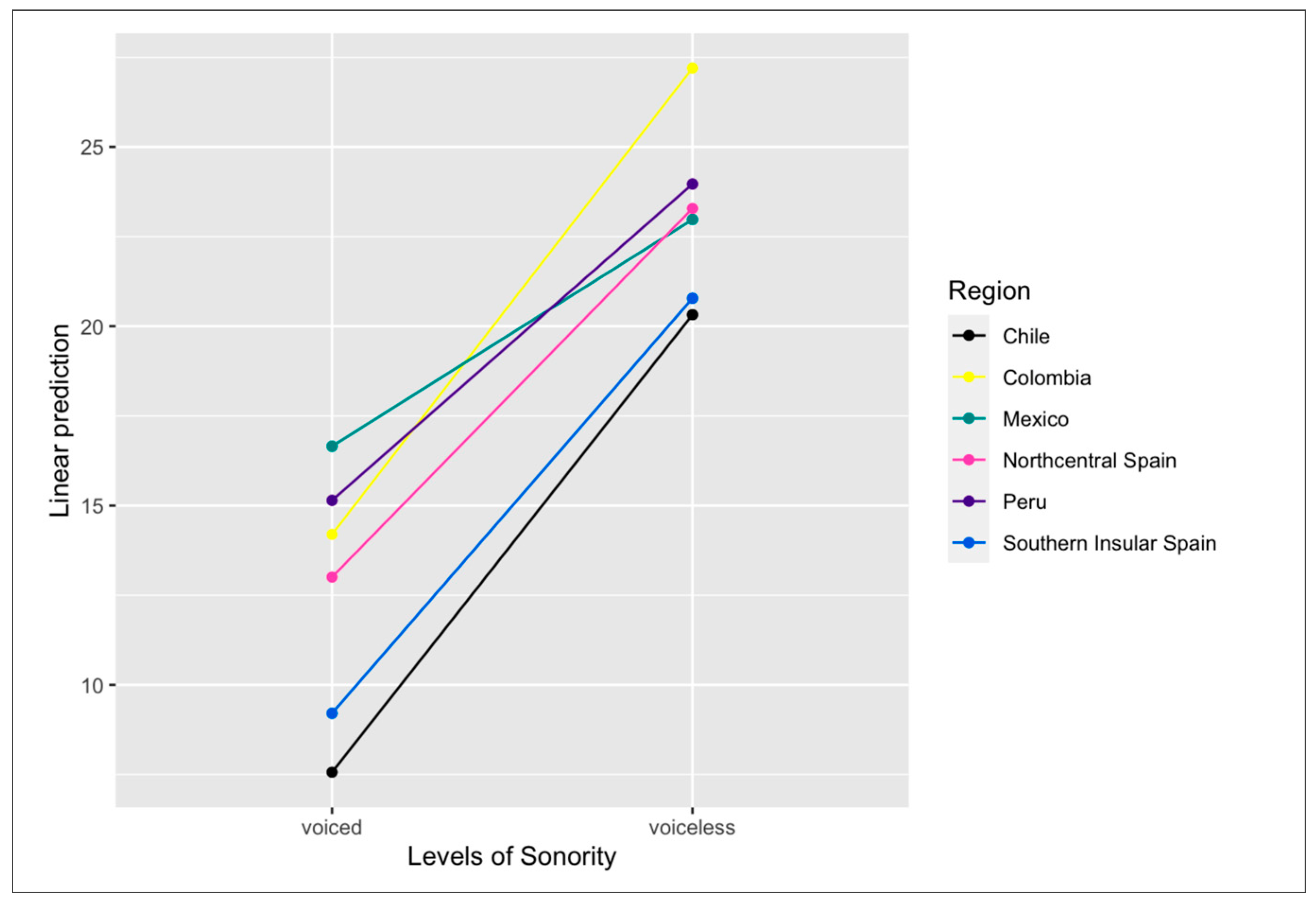

Statistical modeling confirms that RI of /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ does depend on region overall and that the difference in RI between voiceless /ptk/ and voiced /bdɡ/ also differs by region. These results expand on those found in

Lewis (

2001) where /ptk/ is more lenited in a Northern Peninsular Spanish variety than a Central Colombian variety, as well as those from

Carrasco et al. (

2012) where Madrid Spanish /bdɡ/ has more extensive weakening than in a Costa Rican variety. Both

Lewis (

2001) and

Carrasco et al. (

2012) suggest that Peninsular varieties of Spanish are at a more advanced stages of consonant weakening than varieties in Latin America. The results from this highly controlled study confirm these results except for Chilean Spanish, which displays the greatest degree of stop consonant weakening among all six varieties investigated. What is clear across all speakers is the higher degree of occlusion for voiceless segments /ptk/ when compared to voiced segments /bdɡ/, which is to be expected considering the sonorous qualities of the voiced series. More occlusion, however, is a relative description when discussing the different Spanish varieties, since a higher degree of occlusion of /bdɡ/ in Mexican varieties is comparable to the lower degree of occlusion of /ptk/ in Chilean varieties.

Although there is no overlap between varieties, these data always display a distinction between /ptk/ and /bdɡ/, even though some Spanish varieties might be considered overall higher-leniting dialects or lesser-leniting varieties. It is also important to note that within each variety, the production of /bdɡ/ never reaches/overlaps with the production of /ptk/, maintaining the phonological distinction between the voiceless and voiced phonemes This indicates that within each variety, even if the speakers of that variety produce stop consonants with high degrees of lenition, they always distinguish between the two stop consonant series. Considering the push–pull chain and Structuralist models of language change (

Alarcos Llorach 1961;

Martinet 1952;

Veiga 1988), speakers consider these two sets of segments /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ to be different and despite language evolution and increased lenition in some varieties, the distinction is consistently maintained, and a weaker production of /ptk/ will not threaten the existence of /bdɡ/. This simply indicates that production of /bdɡ/ will also be weaker. This is not a phonological change, rather a allophonic innovation within the existing phonological system. The results from the current data set, therefore, establish that Spanish variety does play a role in the degree of consonant weakening, where some varieties have lower RI values and therefore less occluded occlusive productions while others have higher RI values and therefore more highly occluded occlusive productions. The speakers of Chilean and Southern/Insular Peninsular varieties consistently produced /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ with lower RI values and overall weaker consonant productions, whereas speakers of Colombian and Mexican varieties exhibited higher degrees of occlusion for /ptk/ and /bdɡ/, respectively. The other varieties investigated are found in between the two, highlighting the gradient nature of consonant lenition. Consonant productions of speakers of Chilean varieties as well as Southern/Insular Peninsular are realized with more vowel-like qualities, even in word initial position. Speakers of the Mexican and Colombian varieties included here, on the other hand, tend to produce more conservative, occluded realizations of stop consonants, with only slight and sporadic weakening. Concerning the varieties analyzed for this study, the data display a range of consonant productions, instead of consistent productions of like-sounding consonants. This finding is relevant in that it motivates future research on the effect of language variety on consonant lenition. Preliminary findings indicate that there indeed exists the possibility of a correlation of consonant production of /ptk/ and /bdɡ/ between more leniting and less leniting Spanish varieties with respect to RI.

Given the exploratory nature and highly controlled task design and analysis of this study, various limitations such as task design, participant demographics, sociolinguistic variables, and determination of Spanish ‘variety’ will inform future work on this topic. Expansion of this work should seek to measure the gradient nature of stop consonant lenition as it occurs in spontaneous, rather than laboratory, speech. The carrier phrase used to elicit the production of stop consonants can prime certain prosodic effects of the segment in question, resulting in relative intensity measurements that are not reflective of spontaneous speech. A larger, more representative participant pool would also contribute to the robustness of the results, especially since the Mexican Spanish variety only had one representative participant, and thus, the results are highly susceptible to individual variation. Many of the participants reported having spent many years away from their home country living in the United States. This environment of English–Spanish contact could have ultimately affected the overall results since some of the participants had only spent four months in the United States while others had lived in the United States for almost thirty years. Research has shown that extended periods of time in an immigrant country can have linguistic effects on the L1; therefore, the circumstances of participant bilingualism could have had an effect due to English contact, where lenition of intervocalic occlusive segments is not as strong. Future research would incorporate data from a larger pool of monolingual, native speakers of Spanish who still reside in their hometown/home country and have minimal contact with other language in addition to strengthening the participant pool for each Spanish variety tested.

The consideration of other sociolinguistic variables such as gender, level of education, and socioeconomic status could also prove fruitful for the investigation of consonant lenition across different varieties of Spanish. Previous studies such as

Acosta-Martínez (

2014),

Alba (

1988),

Cedergren and Sankoff (

1974),

Labov (

1966,

1972),

Malaver and Samper Padilla (

2016),

Poplack (

1978), and

Rojas (

1981) determine that these sociolinguistic variables are key to exploring phonological variation. The regional divisions of the data (Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Chile, North-Central Peninsular, and Southern/Insular Peninsular) used here are also problematic in that identifying dialects according to seemingly arbitrary borders corresponding with specific countries could be misleading when considering specific features of a given variety. For example, considering the speech of Mexico to be one singular “variety” is troublesome since this area is so vast, encompassing multiple varieties with distinctive features within one so-called “variety”, not to mention that the current data set includes data from only one single speaker of Mexican Spanish. This is also true of smaller regions that have differing characteristics within a smaller area, such as the Canary Islands or coastal vs. inland Colombia. For the study, North-Central Peninsular Spanish and Southern Peninsular and Insular (i.e., Canary Islands) Spanish were separated into two distinct regions; however, the results indicated that the Southern Peninsular was not radically different from the Northern Peninsular varieties. Expansion of this preliminary exploration of the effects of region on stop consonant lenition should take into account these limitations.