1. Background

Infinitives, together with participles and gerunds, comprise some of the non-personal forms of the verb. They are called non-inflectional or nominal forms as they are devoid of person and tense morphemes (

Hernanz 1999,

2016), and they cannot enter into agreement relations with a subject and cannot express temporal reference by themselves. Hence, its impossibility to appear in independent sentences and its use with either an auxiliary verb or a main verb. Previous work has suggested that infinitives are considered a mixed category [+V, +N], which in certain contexts undergoes the neutralization of one feature. Others argue that infinitives receive double status: [+N] in some contexts and [+V] in others, but not [+N] and [+V] at the same time. A third proposal maintains that infinitives can appear as nouns given their intrinsic nominal status. The nominal nature of the infinitive in Spanish is supported by the fact that it can play the same role in a sentence as any noun (

De Miguel 1996). They can appear as subjects of a main clause (1), complements of a verb (2), and objects of a preposition (3):

- 1.

Reir es muy bueno.

“Laughing is very good.”

- 2.

Mi prima ama dibujar con lápices de colores.

“My cousin loves drawing with colored pencils.”

- 3.

Mi amiga está cansada de trabajar todo el día.

“Myfriend is tired of working all day.”

This form of the infinitive has been called the Spanish nominalized infinitive (NI), and it is characterized by an infinitive verb occurring in a nominal environment (

Berger 2015;

Pérez Vázquez 2002;

Ramírez 2003). The NI shares properties with other nouns, as they can be modified by a determiner, an adjective, or a prepositional phrase.

Alarcos Llorach (

1994) and

Bello (

1847) highlight that infinitives are similar in meaning to abstract nouns (

comer “eat” and

comida “food” express the same idea) and can be in fact replaced by other nouns (

le gusta comer “she likes to eat” or

le gusta la comida “she likes food”).

Recent studies in heritage languages have centered on non-finite forms with other language pairs. For instance,

Putnam and Søfteland (

2022) investigate the strategies of non-finite complementation in the language of American Norwegian (AmNo) speakers. Research on gerunds has also garnered considerable attention recently, particularly in relation to semi-lexicality, as they have the property of being considered both verbs and nouns (

Klockmann 2017;

Song 2019).

Alexiadou et al. (

2011), together with

Borer (

2005), have associated the Spanish NI with certain English gerund constructions. The infinitive in Spanish and the gerund in English seem to fall on a continuum of nominality as they share two features: (1) they may have any explicit subject, and (2) they may govern any element a verb can govern (direct objects, indirect objects, adverbs, and adverbial phrases) (

Peña 1981). In English, gerunds can appear in the same three positions in which infinitives appear in Spanish: as the subject of a sentence, as verb complements, and as objects of a preposition. Nonetheless, infinitives can also occur in some of these positions. They can occur as the subject of a sentence, as a verb complement, or as the complement of an object.

Table 1 shows the list of contexts in which infinitives and gerunds are used in Spanish and English.

The use of the gerund or the infinitive as complements of the verb in English depends on the main verb of the sentence. Some verbs can be followed only by the infinitive (4) or by the gerund (5). Other verbs can trigger either the gerund or the infinitive with a subtle change in meaning (6). The overlap between the gerund and the infinitive can be disambiguated in the semantic domain. However, scholars like

Emonds (

2013) argue that there are many differences between these forms.

- 4.

I want to go out.

*I want going out.

- 5.

She enjoys playing tennis.

*She enjoys to play tennis.

- 6.

He loves to draw.

He loves drawing.

One significant distinction between Spanish and English lies in the usage of infinitives as complements of verbs. In Spanish, infinitives can directly follow the verb without the need for an intervening preposition (

prefiero bailar). In English, however, this construction would require the use of the preposition

to or the use of the gerund, resulting in “I prefer to dance” or “I prefer dancing”. Another divergence emerges in the treatment of infinitives as complements of prepositions. Spanish allows the use of infinitives in prepositional phrases. For example,

estoy cansada de trabajar todo el día “I’m tired of working all day”, where

de trabajar “of working” functions as a prepositional phrase with the nominalized infinitive

trabajar “working”. In English, only gerunds can occur freely as objects of a preposition, resulting in “I’m tired of working all day”. Finally, some authors argue that Spanish exhibits a higher frequency of nominal infinitives compared to English (e.g.,

Gawelko 2005;

Quintero Ramírez 2015). Spanish speakers readily employ infinitives as nouns in a wide range of contexts, including abstract concepts and general statements. English, on the other hand, relies more heavily on gerunds or alternative nominal forms.

2. Previous Research

Infinitive constructions have been found to be used more frequently than gerund forms in Spanish. This was supported by

Schwartz and Causarano (

2007), who examined the frequency of infinitives and gerund use in a corpus of written texts of Spanish native speakers enrolled in an intensive English program. The writing samples were chosen randomly and included both in-class and out-of-class assignments. The results showed a higher frequency of infinitive use compared to gerund forms. These results have been supported by more recent work with heritage speakers (

Belpoliti and Bermejo 2019;

Escobar and Potowski 2015). For example,

Escobar and Potowski (

2015) reported on a study on the acceptability of gerunds in contexts where the infinitive was expected among 130 heritage speakers via an acceptability judgment task. The participants were presented with four sentences with the gerund and four with the infinitive in six different grammatical contexts: subject of the main clause (without object), subject of the main clause (with object), subject of the subordinate clause (with direct object), subject of subordinate clause (without direct object), object of the preposition, and attribute. The results showed similar acceptance rates for the gerund and the infinitive in subject position with or without object and as subject of a subordinate clause with direct object. The acceptance of the infinitive was higher as the object of a preposition and after the verb

ser. The results suggest that subject contexts seem to be the most susceptible to the use of the gerund. Similar patterns were found by

Belpoliti and Bermejo (

2019) while examining the written production of infinitives and gerunds by Spanish heritage speakers. The authors investigated the use of inflected and uninflected verb forms in a corpus of 200 essays written by heritage speakers placed at the lowest proficiency level in a university placement test. Regarding the use of uninflected forms, the results showed that the infinitive was highly frequent, with 85.6% of use, followed by 14.4% of gerund use. The authors reported that using an infinitive as a complement of a conjugated verb accounted for 60.9% of all instances of infinitives in the data. The next most common usage was infinitives after prepositions (31.9%) or serving as the subject of a sentence (5.2%). There were only a few instances (2%) where the infinitive appeared as the main verb of the sentence, and other cases where the gerund was used in place of the infinitive. The use of the gerund as a complement of a preposition was observed in 31 instances, and the gerund in subject position in 11 instances. The authors claimed that these were non-canonical uses of the gerund, as in most Spanish varieties, the infinitive is the expected form to be used in these contexts.

To our knowledge, no previous work has examined the elicited production or interpretation of infinitive forms in Spanish. We fill this gap by testing heritage speakers’ production and interpretation of infinitives as subjects of the clause and objects of a preposition. We follow the Activation Approach (

Putnam and Sánchez 2013) to account for the potential divergences that heritage speakers might have in relation to infinitive use and interpretation. This approach argues that the divergences in heritage grammars can be explained in relation to factors such as patterns of language activation and use, proficiency, and lexical frequency for both production and comprehension purposes. The lack of activation of the heritage language might contribute to morphosyntactic variability and potential restructuring of L1 features (

Goldin et al. 2023;

Hur 2020;

Hur et al. 2020;

López Otero 2022;

López Otero et al. 2023;

Perez-Cortes 2016;

Putnam and Sánchez 2013;

Putnam et al. 2019;

Sánchez et al. 2023;

Thane 2023). Thus, it is possible that some properties of the heritage grammar undergo grammatical reconfiguration or reassembly of their internal representation due to low lexical activation, crucially when difficulties in both production and interpretation seem to converge.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

As discussed earlier, the infinitive form in Spanish can be used as the subject of the main clause, the complement of a verb, or the object of a preposition. In English, both infinitives and gerunds can be used as subjects of a clause and as verb complements, but only the gerund can be used as the object of a preposition (

Table 1). This represents a learnability problem for English-dominant heritage speakers of Spanish who might overextend the gerund form to contexts where an infinitive form is required in Spanish, including the subject position or object of a preposition, due to crosslinguistic influence from English. Specifically, we pose the following research questions and hypotheses:

RQ 1: To what extent do English-dominant heritage speakers of Spanish have sensitivity to the use and interpretation of infinitive forms as subject of the clause or object of a preposition?

Hypothesis 1. Spanish heritage speakers will show low use of the infinitive form as subject of a clause and object of a preposition and favor the use and production of the gerund form instead.

RQ 2: Is the use of the infinitive form modulated by language proficiency and language experience?

Hypothesis 2. Language proficiency and language experience will impact the use of the infinitive among the heritage speakers (Putnam and Sánchez 2013; López Otero et al. 2023; Sánchez et al. 2023; Thane 2023). The heritage speakers with higher exposure and usage of Spanish, as well as those with higher proficiency, will exhibit greater patterns of expected use and interpretation of infinitive forms compared to those participants with lower proficiency and patterns of language experience.

In what follows, we discuss the study, including participant groups and methodology.

3. The Study

3.1. Participants

A total of 51 participants took part in the study. Twenty-six (

n = 26) heritage speakers (HS) (age range = 18–31,

M = 20;9;

SD = 3.26) and twenty-five (

n = 25) Spanish-dominant speakers (SDS) served as baseline groups (age range = 18–27;

M = 19;7; SD = 2.14). The participants completed an online language background questionnaire via Qualtrics (adapted from

Cuza 2013 and

Shin et al. 2023). The questionnaire elicited the participants’ demographic information, linguistic background, and patterns of language experience (

Table 2). Concerning their language experience, participants were asked to report their patterns of language exposure and use at home, school, work, and social situations, as well as the frequency of language use and exposure across various contexts, including phone, chatting, texting, listening to music, watching TV, and reading, using a 5-point Likert scale. The Likert scale included five categories, and each category received a numeric score: Never (1), Rarely (2), Not much (3), Frequently (4), Very frequently (5). Additionally, the participants completed a modified version of the

Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE) as an independent language proficiency measure (

Cuza et al. 2013;

Bruhn de Garavito 2002;

Duffield and White 1999;

Montrul and Slabakova 2003). This proficiency test was made up of two sections. The first section consisted of a vocabulary test in which participants chose a word or an expression to complete a given sentence. The second section was a cloze test in which participants chose one of three multiple-choice options. Following

Montrul and Slabakova (

2003), participants whose scores ranged between 40 and 50 points were considered advanced learners. Participants who obtained 30 to 39 points were considered intermediate learners, and participants who scored between 0 and 29 were considered beginner learners. All tasks were completed online via Zoom and Qualtrics. Participants signed a consent form and were compensated for their participation.

The HS group (n = 26) included 23 participants born and raised in the US, two participants born in Peru (age of arrival range: 0;3–3), and one participant born in the Dominican Republic who arrived in the US before age 5. All of the participants were undergraduate students at a major research university in the Midwest. Most of the participants’ parents (89%) were born in a Spanish-speaking country and spoke Spanish as their first language. The parents’ countries of origin included Mexico, Peru, Argentina, and the Dominican Republic. Their mean score in the proficiency test ranged from 30 to 47 points out of 50 (M = 40.54; SD = 4.78). About 80% of the participants reported speaking Spanish during childhood, 15% reported speaking both English and Spanish, and 4% reported speaking English. Regarding language experience, 50% of the participants reported speaking “only Spanish” or “mostly Spanish” at home, 38% reported speaking “equal Spanish and English” and 12% reported speaking “only English” or “mostly English”. About 96% reported speaking “mostly English” at school, whereas in social situations, 50% reported speaking “equal Spanish and English” and 50% reported speaking “mostly English”.

The SDS (n = 25) were native speakers of Spanish from Mexico and Colombia. All of them were attending college in their country of origin. Regarding their linguistic experience, they all reported speaking Spanish during childhood as their first language. Most of them reported using “only Spanish” at home (96%), and 4% reported using “equal Spanish and English”. In social situations, 92% of them reported speaking “only Spanish” and 8% reported speaking “equal Spanish and English”. At school, 68% reported using “only Spanish”, 28% reported using “equal Spanish and English” and 4% reported using “mostly English”.

3.2. Tasks

Data elicitation included an elicited production task (EPT) and a contextualized preference task (CPT). Both tasks were administered online. The EPT was implemented in the form of a synchronous online interview via Zoom, and the CPT was conducted as an asynchronous online questionnaire via Qualtrics. The EPT was administered first, and the CPT was administered second, in order to avoid priming effects on the structure to be used. Test items and contexts remained the same across tasks. All items were randomized and counterbalanced in order to prevent presentation order effects. As a result, two batteries were generated. Half of the participants completed battery A, and the other half completed battery B.

3.2.1. Elicited Production Task

The EPT aimed at eliciting the oral production of infinitives in the two syntactic contexts under investigation. The task had the form of a sentence completion task. Similar designs have been used in previous studies to test the production of different grammatical structures in Spanish with good results (

Cuza 2016;

Cuza and Frank 2015;

Castilla-Earls et al. 2018;

Hur et al. 2020;

Shin et al. 2023). The task consisted of 20 experimental contexts, 20 fillers, and 4 training contexts. The experimental contexts included 10 contexts in which participants had to produce the infinitive form as the subject of a sentence and 10 contexts in which they had to produce infinitives as the object of a preposition. The prepositions included in the experiment were

por “for”,

en “in” and

de “of”. The participants were presented with a short preamble and a prompt in the form of a question. They were shown an image and a sentence with a gap in it. The participants were instructed to complete the sentence with one word that was related to the image presented. The task was presented orally and visually with the aid of PowerPoint, and the preambles and prompts were read out loud to the participant by one of the researchers. This is represented in (4) and (5).

| (4) Preamble: Susi es muy glotona. “Susi is very glottonous”. |

| Prompt: ¿Cuál es su pasatiempo favorito? “What is her favorite hobby?” |

| (Here appeared an image of a girl eating) |

| |

| Sentence: _________ es su pasatiempo favorito. |

| “________ is her favorite hobby”. |

| Expected response: comer “eating” |

| (5) Preamble: Erica siempre está cansada. “Erica is always tired”. |

| Prompt: ¿Por qué está cansada? “Why is she tired?” |

| (Here appeared an image of a woman sleeping in her office) |

| |

| Sentence: Erica está cansada de _______ todo el día. |

| “Erica is tired of ________ all day”. |

| Expected response: trabajar “working” |

In (4) and (5), the expected responses were verbs in the form of the infinitive as there was a subject missing and a preposition without an object. In such cases, Spanish grammar requires the use of infinitives. Note that gerund forms are not possible in these contexts in Spanish.

3.2.2. Contextualized Preference Task

The CPT’s main goal was to inquire about the personal preferences participants had towards infinitives and gerunds in the contexts given (e.g.,

Geeslin and Guijarro-Fuentes 2005). Similar to the previous task, the CPT had a total of 44 items: 20 experimental contexts, 20 fillers, and 4 training contexts. The experimental contexts tested infinitives as subjects of a sentence and as objects of a preposition. The participants completed the task online via Qualtrics. After completing the EPT, they received a link through email to have access to the task and were instructed to complete it without any time constraints. Participants were asked to read a preamble, look at an image, and read a prompt in the form of a question. They were presented with three response options to answer the question. All response options represented the same action, and they varied only in the form of the verb. One response option included a verb in the infinitive form. Another response option included a verb in the gerund form. The last option allowed participants to indicate that either the infinitive or the gerund were possible response options. This is represented in (6) and (7).

| (6) Preamble: A Rafael le encantan los deportes. “Rafael loves sports”. |

| (Here appeared an image of a boy swimming in the pool) |

Prompt: ¿Cuál es su pasatiempo favorito? “What is his favorite hobby?”

|

| Response options: |

| (a) Nadar es su pasatiempo favorito |

| “Swiming is his favorite hobby”. |

| (b) Nadando es su pasatiempo favorito. |

| “Swimming is his favorite hobby” |

| (c) Ambas |

| “Both”. |

| (7) Preamble: Mario está interesado en el cine. |

| “Mario is interested in movies”. |

| (Here appeared an image of a boy watching a movie at the cinema) |

| Prompt: ¿Por qué está interesado en el cine? |

| “Why is he interested in movies?” |

| |

| Mario siempre está interesado en __________muchas películas. |

| “Mario is always interested in ___________ many movies” |

| |

| Response options: (a) ver “watch” |

| (b) viendo “watching”. |

| (c) Ambas “both”. |

In (11) and (12), participants were expected to choose the option with the infinitive form. The use of the gerund or both was considered ungrammatical.

4. Results

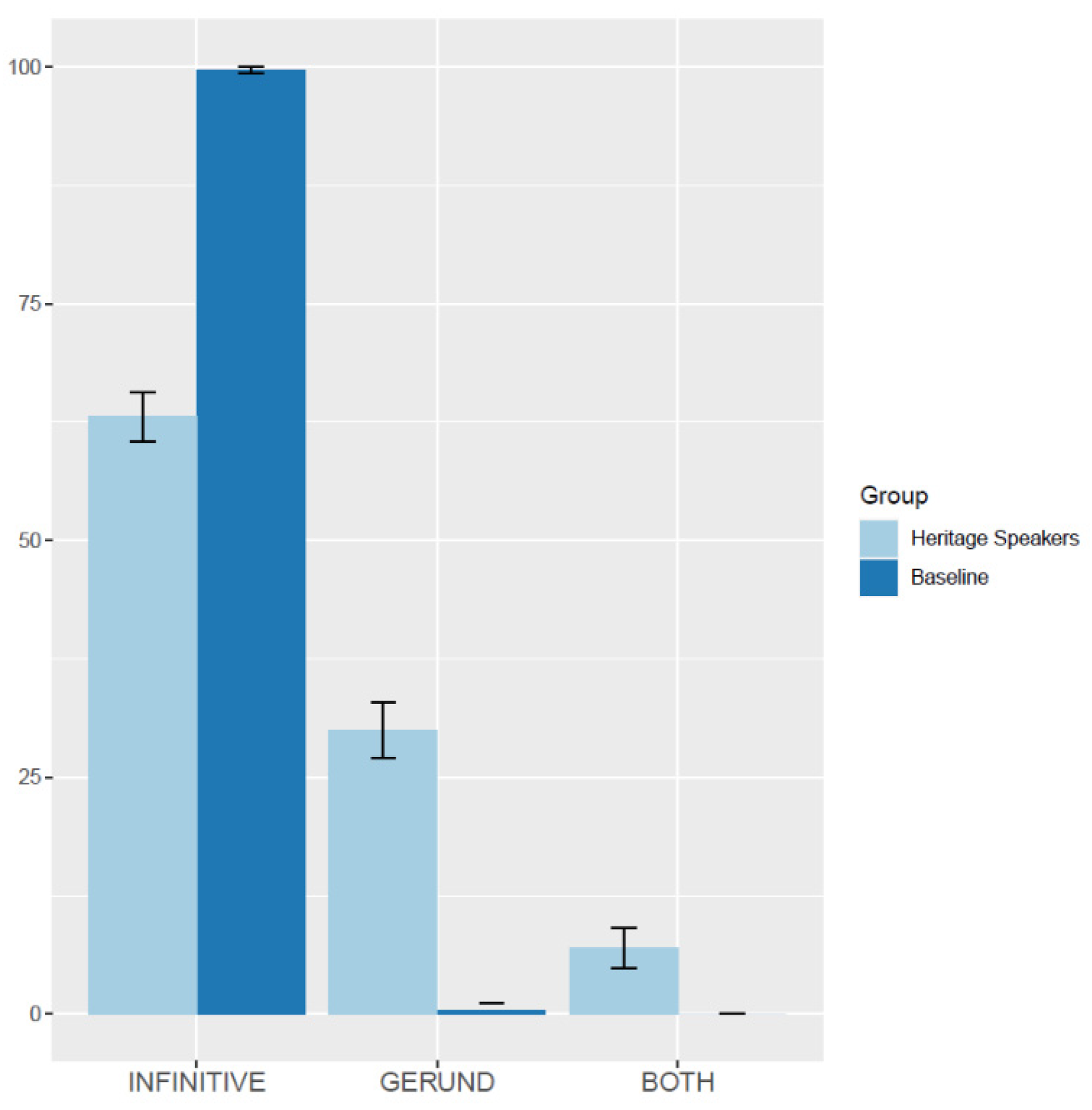

4.1. Results: Elicited Production Task

The overall results provided by the EPT showed less production of the infinitive among the HS (76%), compared to the SDS (98%). In lieu of the infinitive, the HS used the gerund (20%) and other responses (4%) (

Table 3).

In order to know whether the syntactic context influenced the use of the infinitive, we analyzed each condition separately using a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with a multinominal probit distribution in R software. The model included response as the dependent variable and group as the independent variable. The use of the infinitive was coded as 1, the gerund was coded as 0, and other responses were coded as 2. All responses were included in the analysis. The infinitive was taken as the baseline response. Additional models looking at the correlation between participants’ responses, proficiency, and language experience among the SDS were run. These models included response as a dependent variable and proficiency and language experience as independent variables. All models included random intercepts per participant.

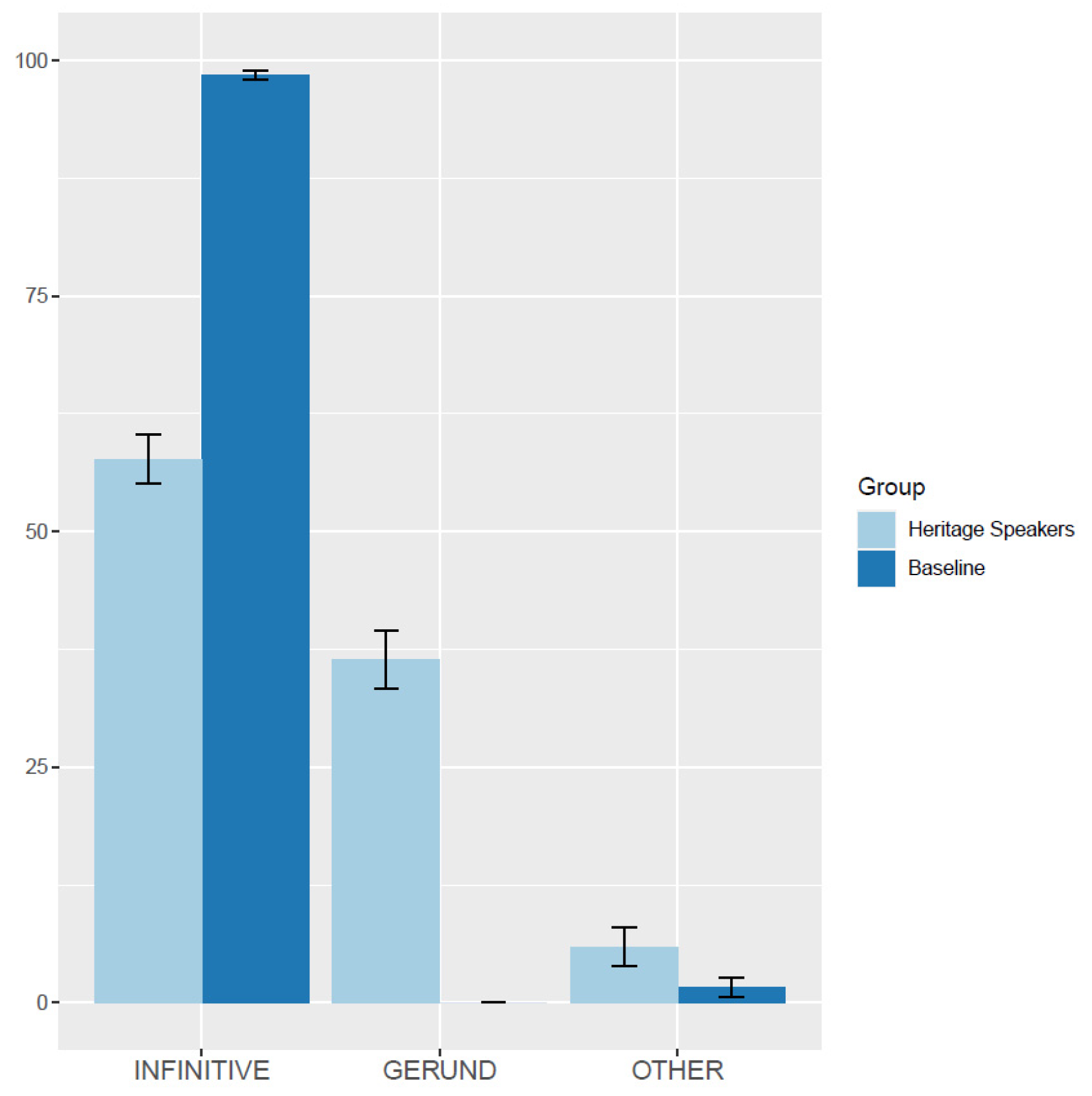

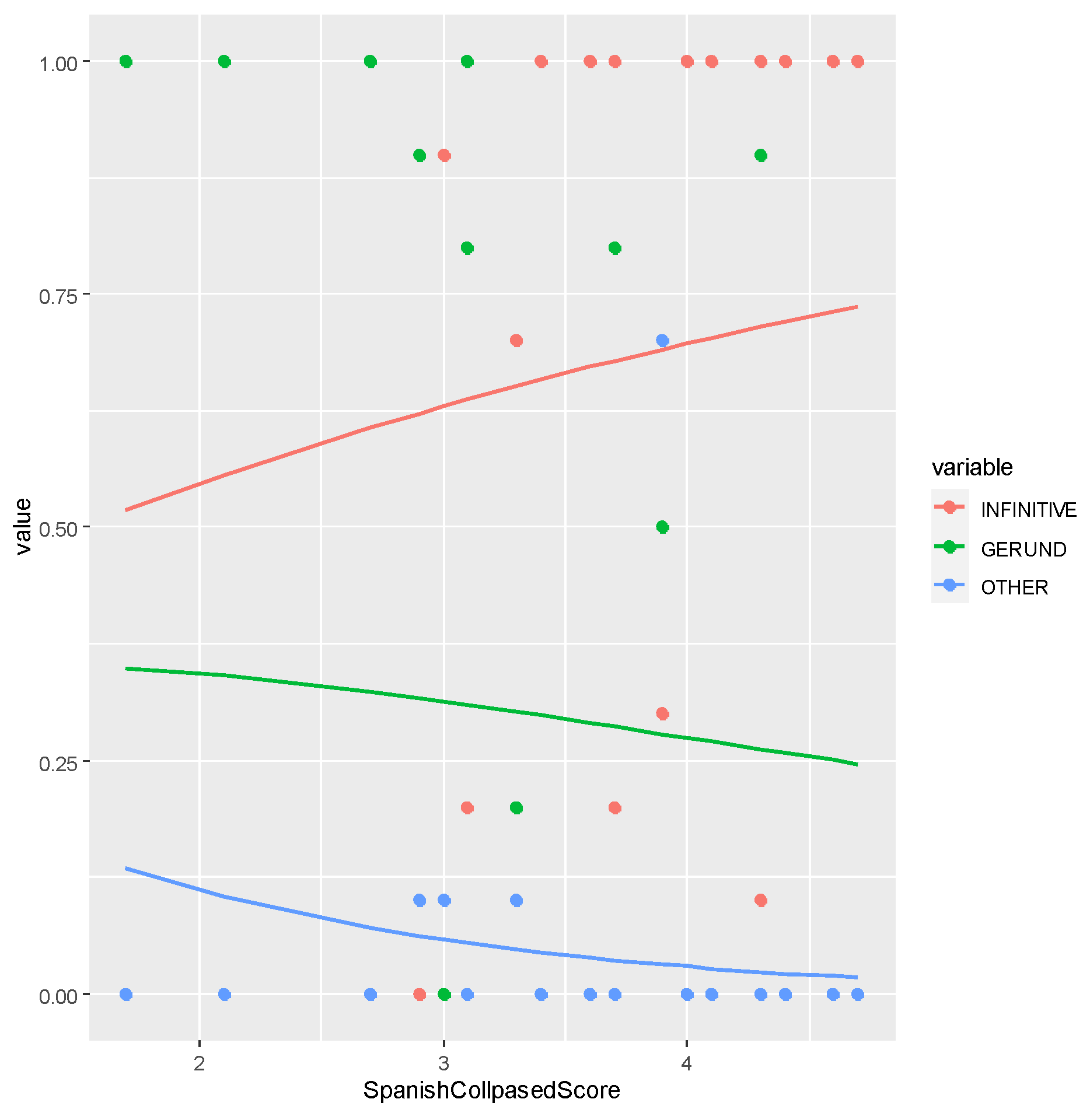

Results for the subject condition showed a main effect of group, indicating that each group behaved differently in the use of the infinitive versus the other two response options. As seen in

Figure 1, the SDS (baseline group) performed at the ceiling in this condition (98%) and only produced other responses 2% of the time. The HS, on the contrary, showed decreased use of the infinitive (61%). The gerund was used 35% of the time, followed by a small proportion of other responses (4%).

Table 4 shows that the probability of using the gerund by the HS was significantly higher than the SDS.

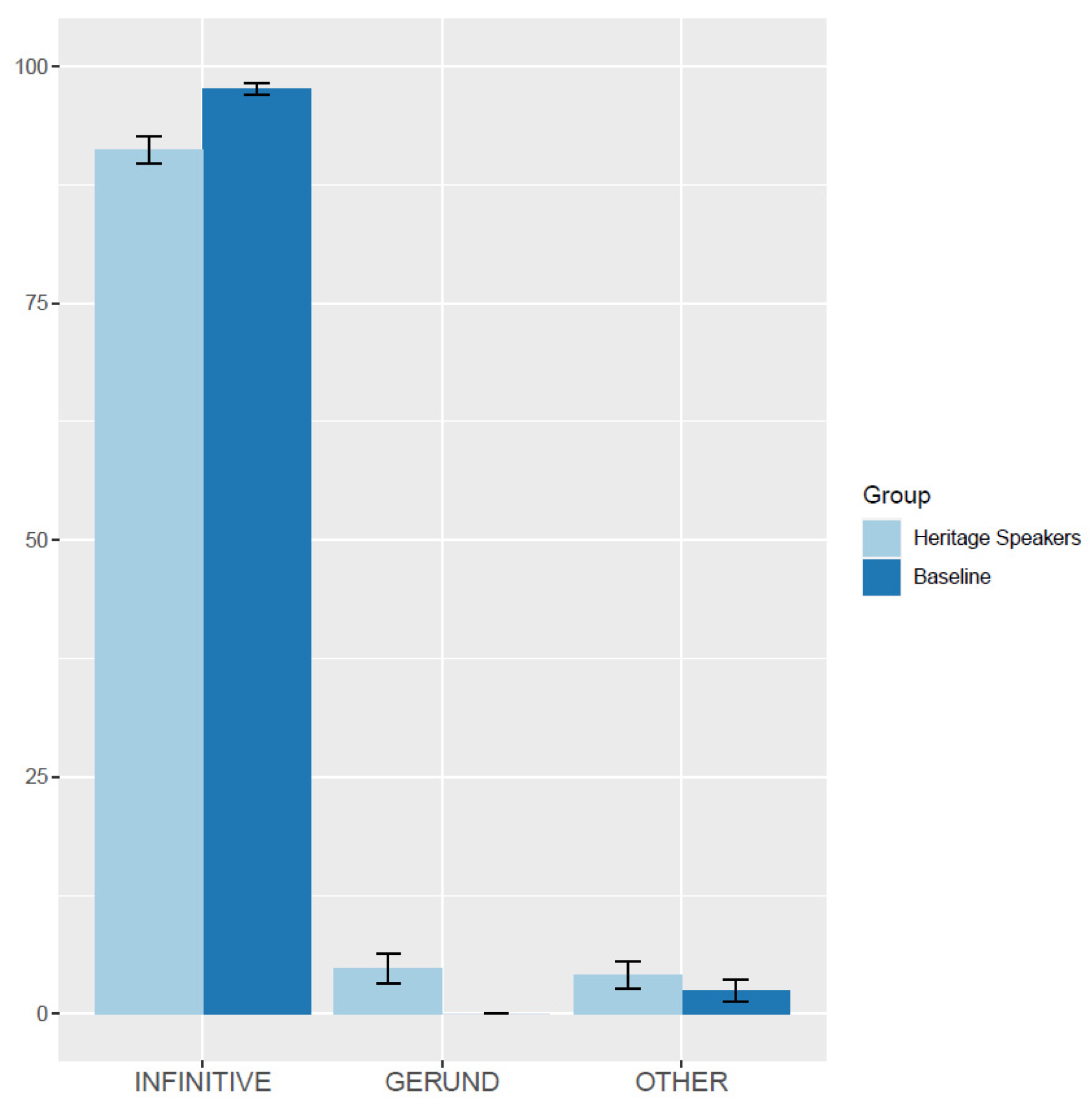

For the object of a preposition condition, the results showed that group was a significant factor in the use of the infinitive.

Figure 2 shows that the SDS relied on the infinitive (98%). Thus, there was less probability of using the gerund or other responses by the participants in this group. The SDS showed robust knowledge of the infinitive (92%) in this condition, followed by a small proportion of the gerund (4%) and other responses (4%). The odds of using the gerund or other response were low (

Table 5).

In order to examine if the behavior observed at the group level was also present at the individual level, we conducted an individual analysis (

Table 6). For this analysis, the participants who produced 10/10 instances of the infinitive were classified as ceiling-performance participants, and those who produced 7–9/10 instances were classified as high-performance participants. Participants who produced the infinitive 1–6/10 were classified as low-performance participants. Those who did not produce the infinitive in any of the trials were classified as Zero-performance participants.

The results of the individual analysis support the group results by showing that there were divergences among the HS and the SDS. The SDS were in the ceiling or high-performance group in both conditions. However, more variability was observed among the HS, who were spread across different performance ranges. These divergences were constrained by conditions. There was more variability in the subject of the clause condition than in the object of the preposition condition. In the former, 57% of the HS were in the ceiling performance or high-performance group, whereas 42% of the HS were in the low performance and zero usage range. In the latter, the majority of the HS (92%) were in the ceiling performance range. Only two participants (8%) were in the low performance range. A closer look at the data showed that the HSs who were in the low-performance or zero-usage range had an average proficiency of 38.4 points out of 50 points. The HS who performed at the ceiling or in the high range had an average proficiency of 42 out of 50 points. Similarly, the HSs who reported having low exposure and usage of Spanish (average 2.3 out of 5.0) were found in the low-performance and zero-performance ranges. Ceiling and high performers reported having much higher exposure (4.1/5.0) and use (3.8/5.0) of Spanish.

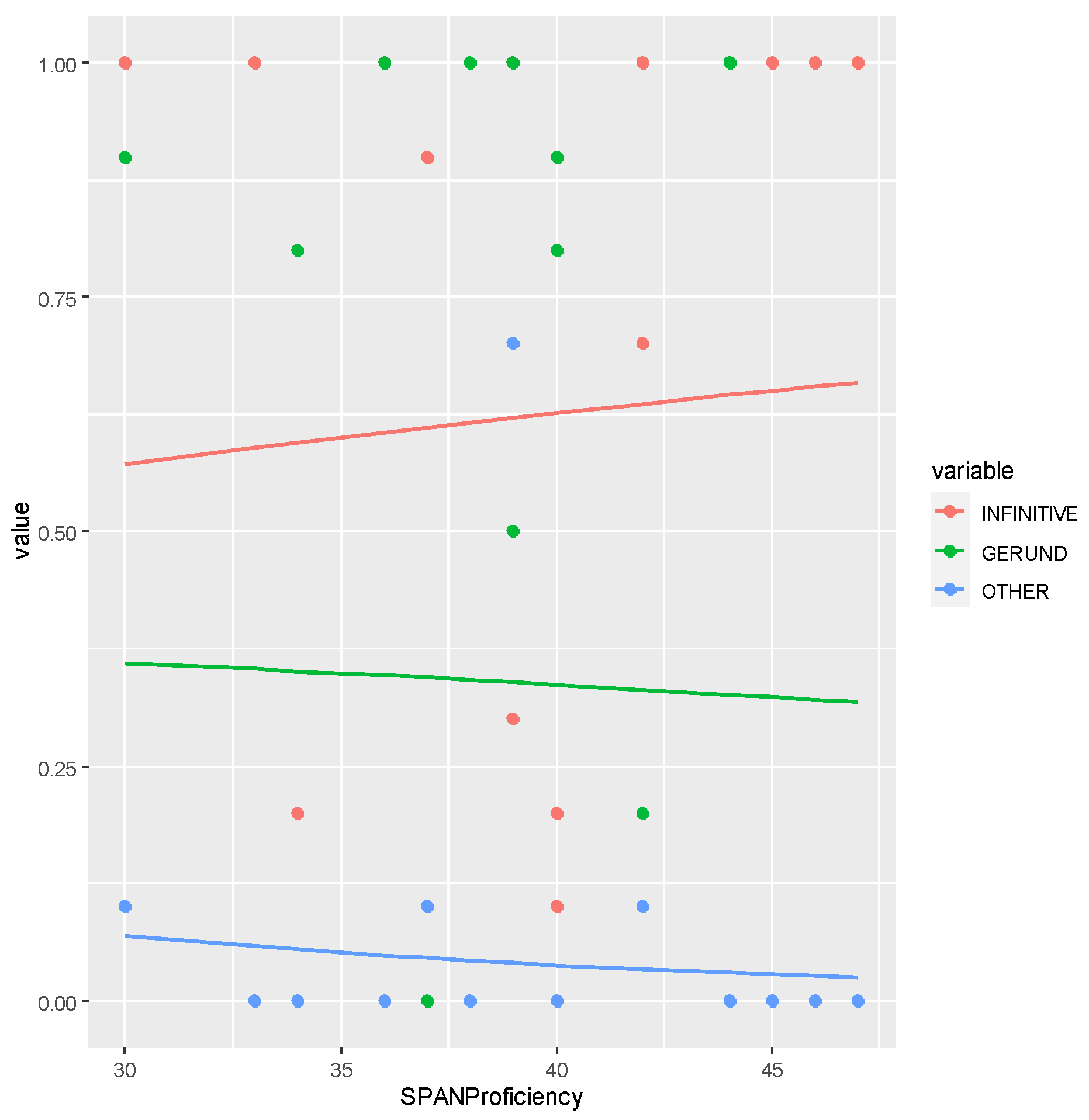

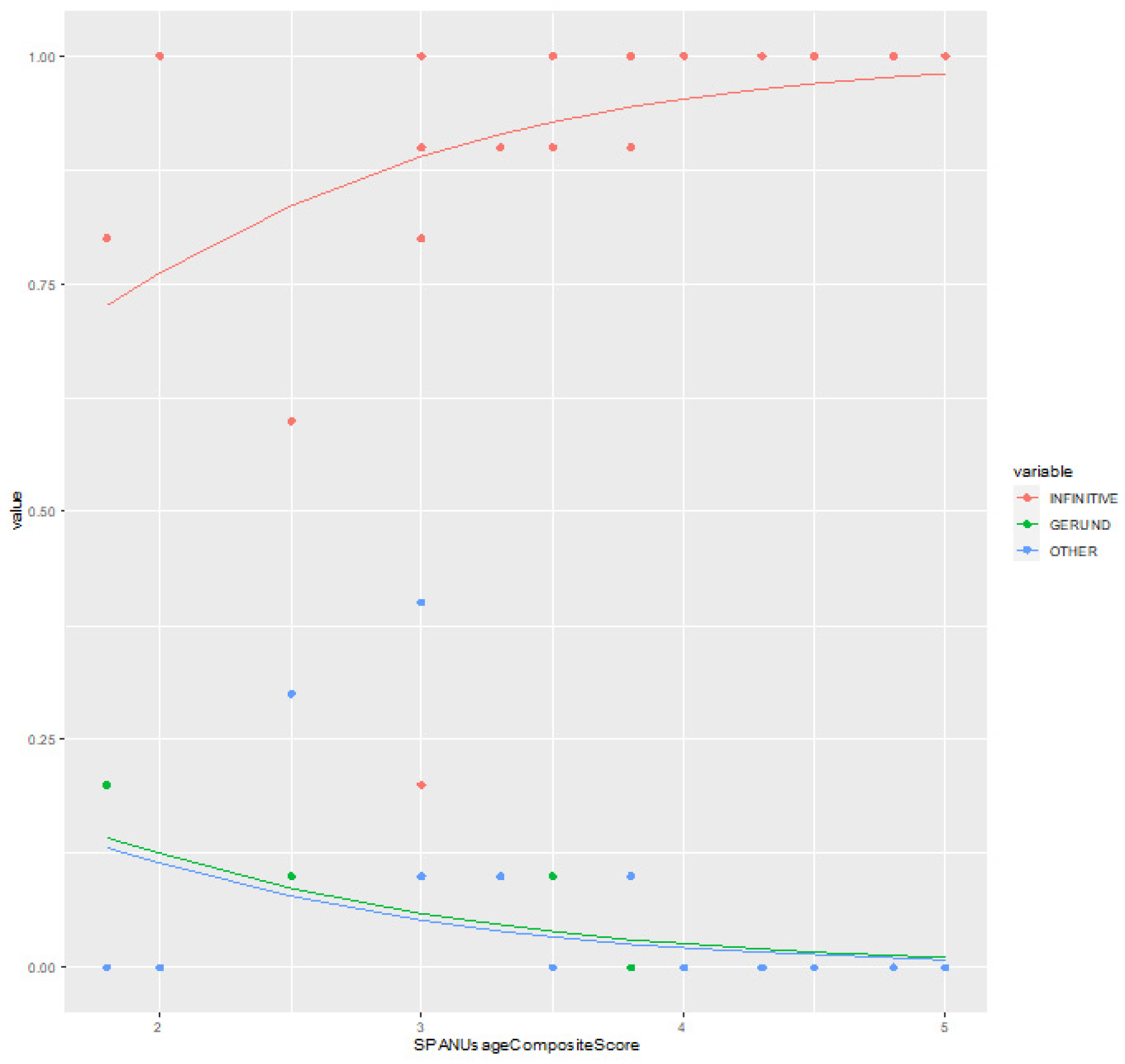

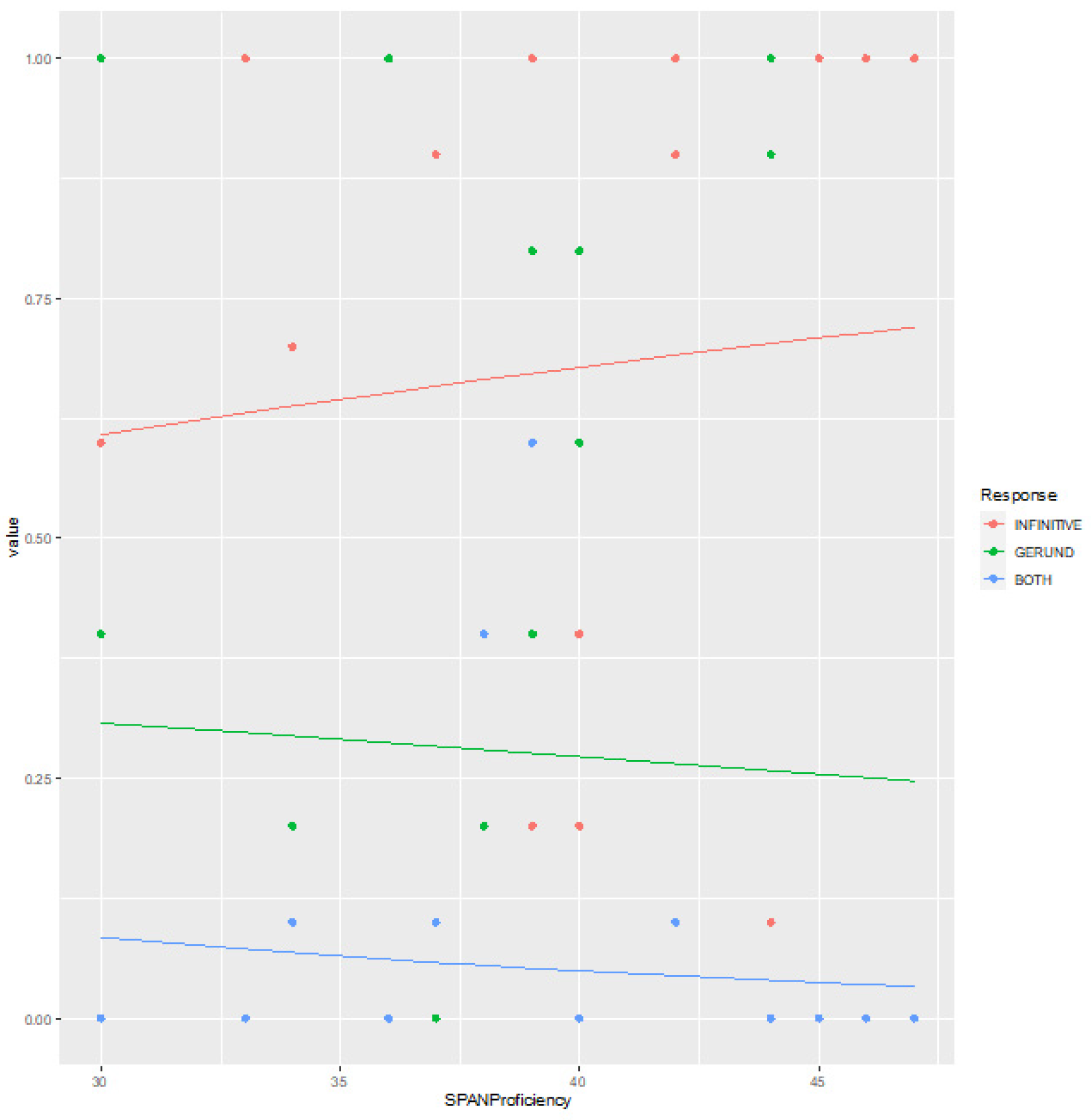

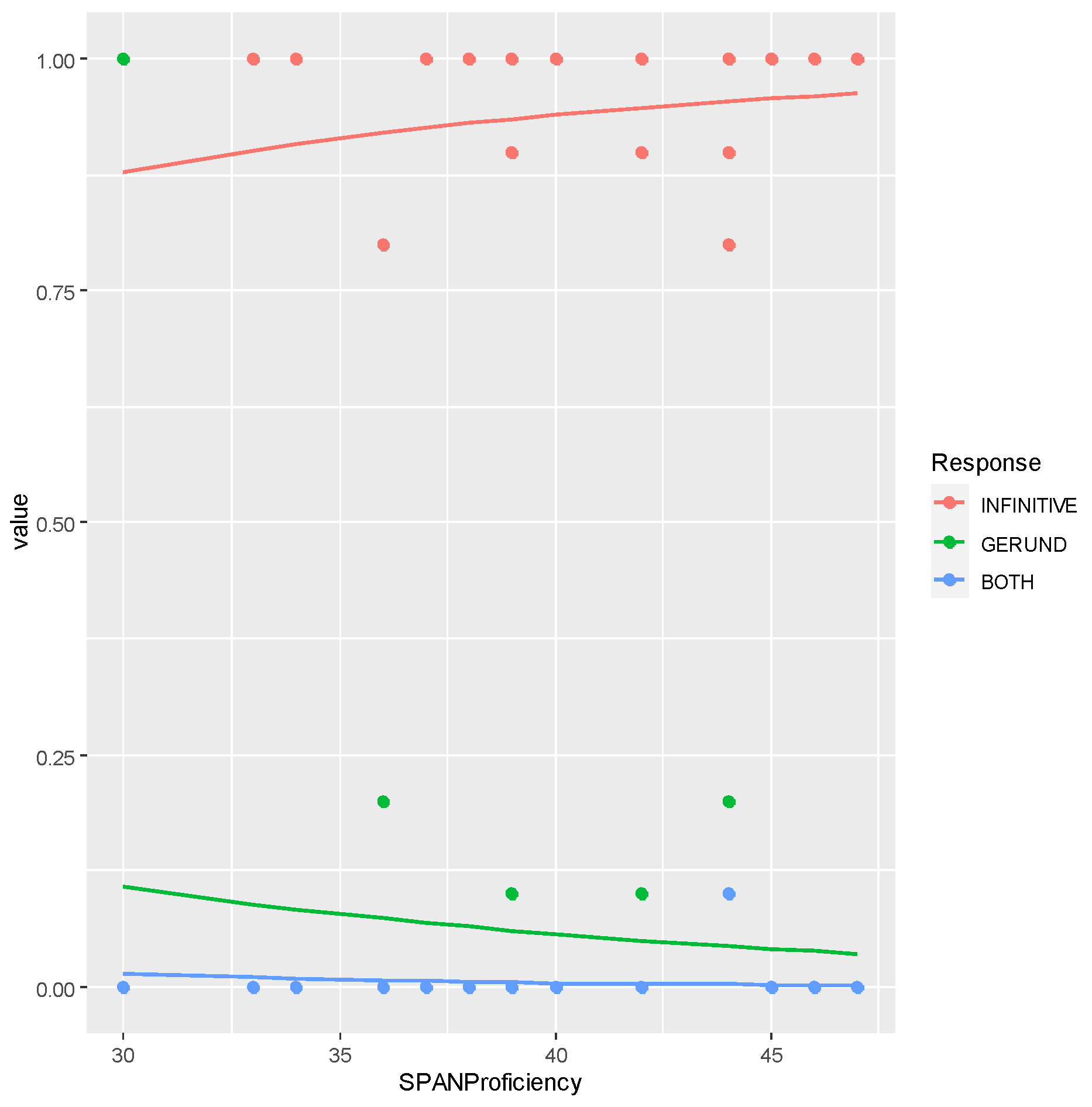

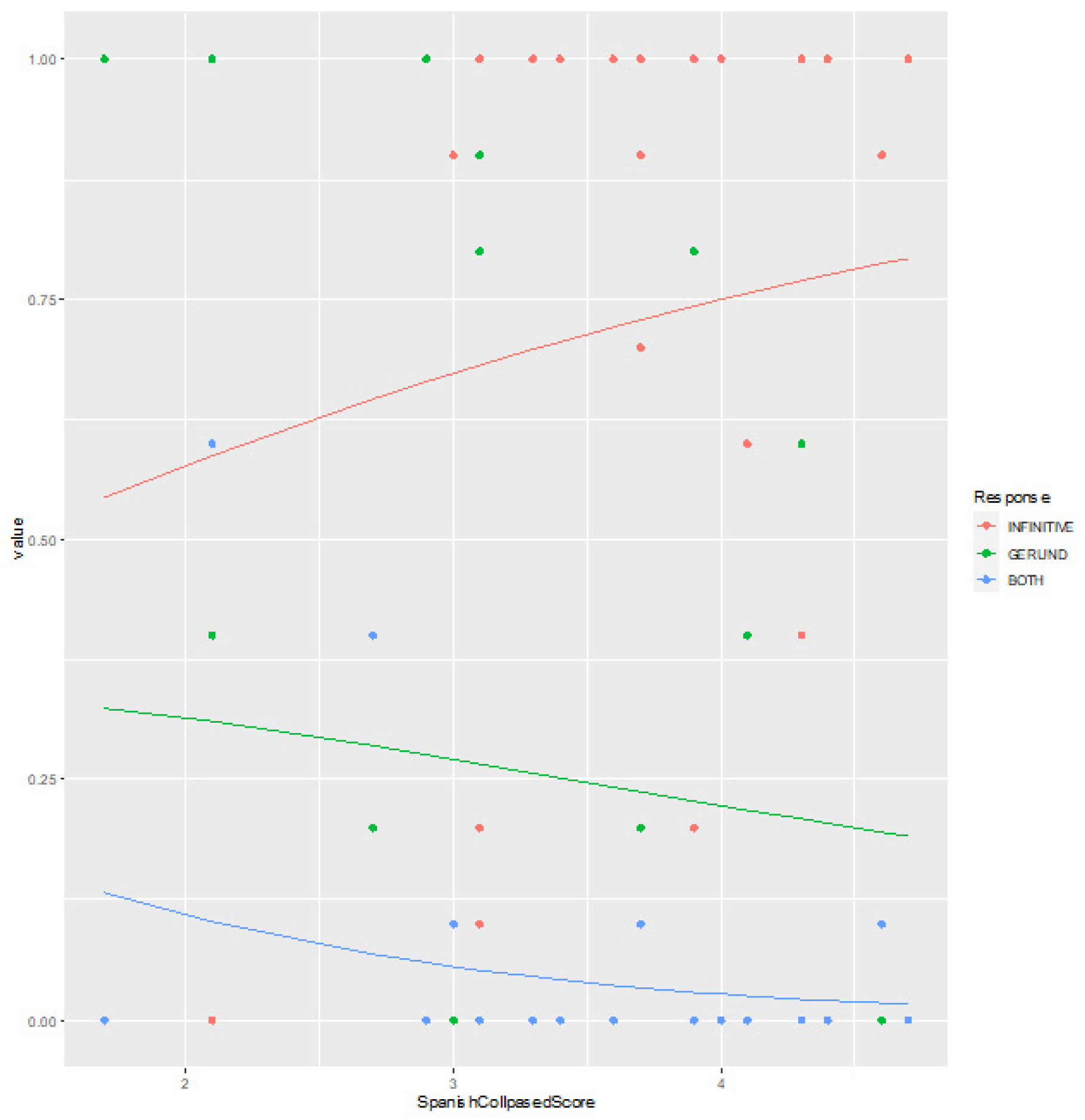

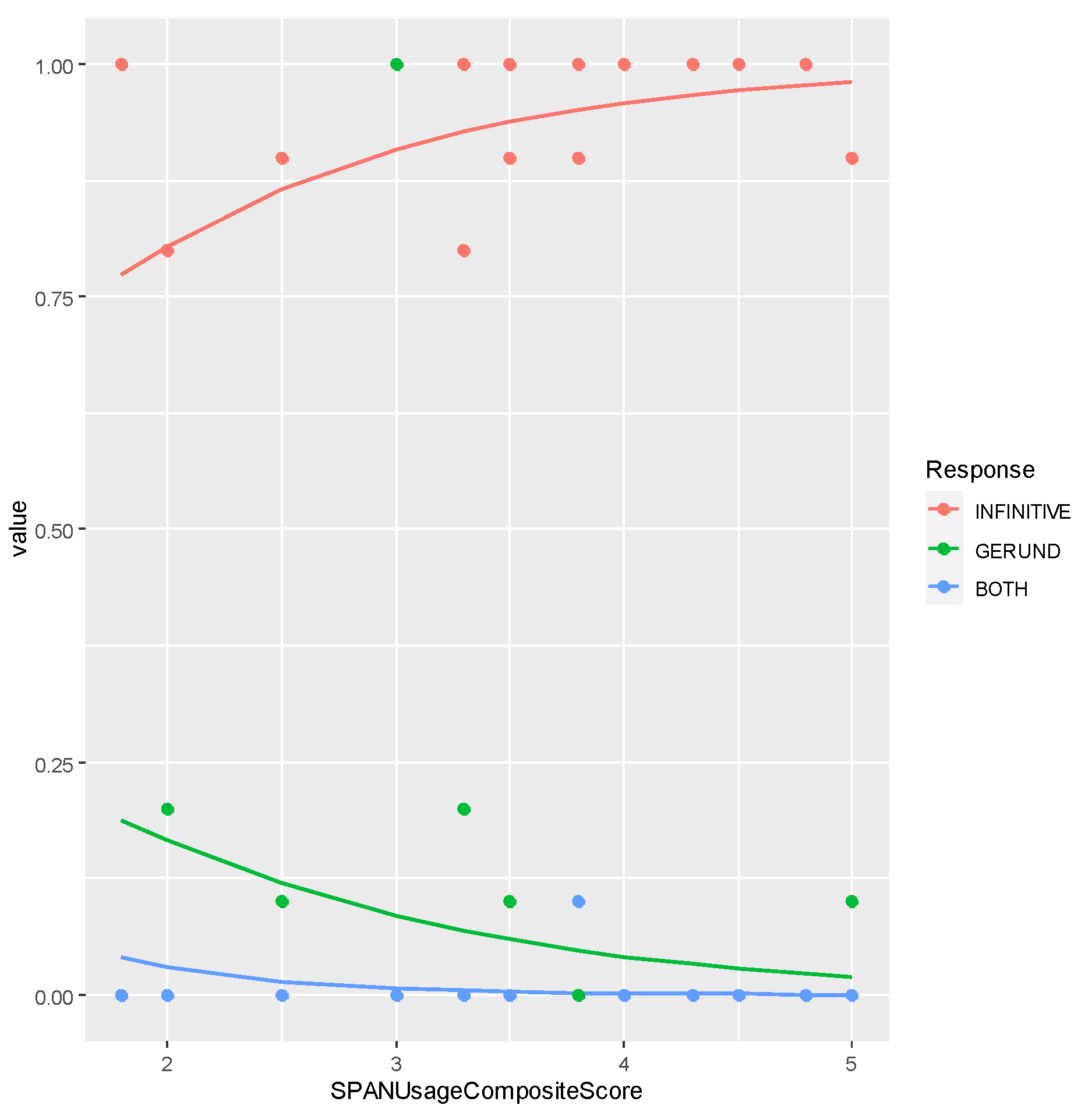

Regarding the role of language proficiency and language experience, the results showed that both factors were statistically significant in relation to the use of the infinitive among the HS (

p < 0.01). As expected, the use of the infinitive increased among those participants with more proficiency and exposure to Spanish (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). However, the distribution of the participants was broader in the subject of the clause condition due to the diverse performance of the participants in this context.

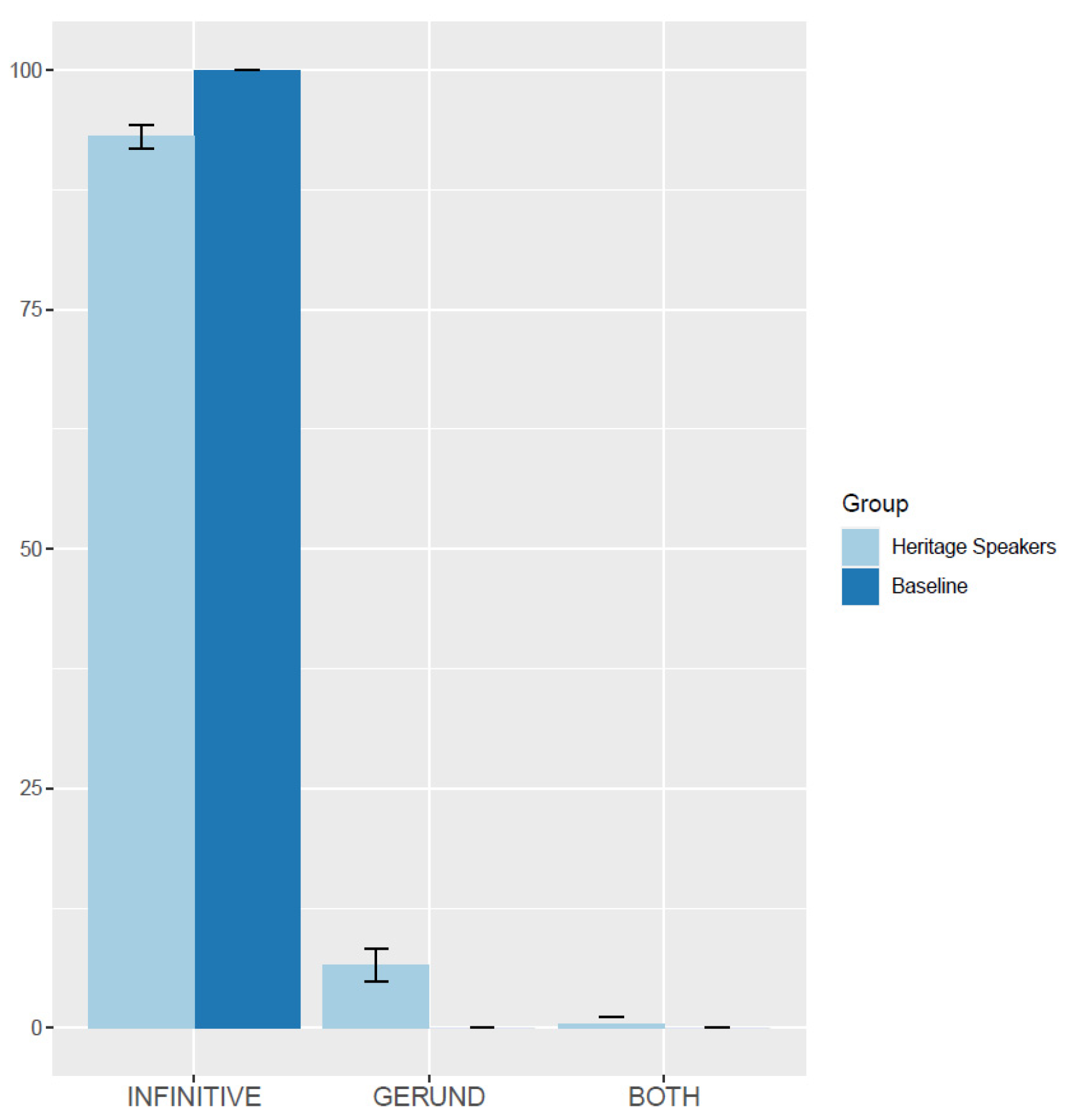

4.2. Results: Contextualized Preference Task

The descriptive results of the CPT showed lower production of the infinitive (78%) among the HS compared to the ceiling performance of the SDS (99%) (

Table 7). In contrast with the SDS, the HS produced the gerund 17% of the time.

Data from the CPT were analyzed using a Generalized Linear Model with a multinominal probit distribution. The model included response as the dependent variable and group as the independent variable. The use of the infinitive was coded as 1, the gerund was coded as 0, and “both” responses were coded as “2”. All responses were included in the analysis. However, the infinitive was the expected response in all trials and was taken as the baseline response for the model. Additional models to determine the correlation between proficiency, language experience, and response among the HS were run. These models included response as a dependent variable and proficiency and language experience as independent variables. All models included random intercepts per participant.

For the subject condition, a main effect of group was found. The SDS were categorical in their receptive knowledge of the infinitive, choosing it 99.6% of the time. The HS, on the contrary, preferred the infinitive in 67% of the trials. They also favored the gerund (28%) and the “both” response option (5%) (

Figure 7). As seen in

Table 8, the probability of choosing the gerund was significantly higher among the HS. The model also revealed a main effect of group for the object of a preposition condition. As represented in

Figure 8 and seen in

Table 9, both groups showed strong receptive knowledge of infinitives in this condition, with more than 92% of preference. However, the HS differed slightly from the SDS as they chose the gerund 7% of the time. The odds of preferring the gerund were lower than in the previous condition.

Individual analysis was also conducted in this task to explore whether group behavior was observed at the individual level. As shown in

Table 10, most of the SDS were in the ceiling or high-performance range across conditions. Regarding the HS, 61% of them showed a ceiling or high production in the subject condition, and some of them showed low (23%) or zero production (15%). The participants who exhibited low production of the infinitive reported having intermediate proficiency (38/50) and low patterns of exposure and usage (3.6/5.0). Those with zero production had a lower proficiency (37 out of 50 points) and were reported to have low use and exposure to Spanish (~2.3 out of 5.0). The participants who performed at the ceiling or in the high range had higher proficiency (42/50) and higher patterns of language use and exposure (3.9/5.0). In the object of a preposition condition, 96% of them were in the ceiling or high-performance range. Only one HS was in the zero-usage range. The individual analysis showed that there was more variability in the subject of the clause condition.

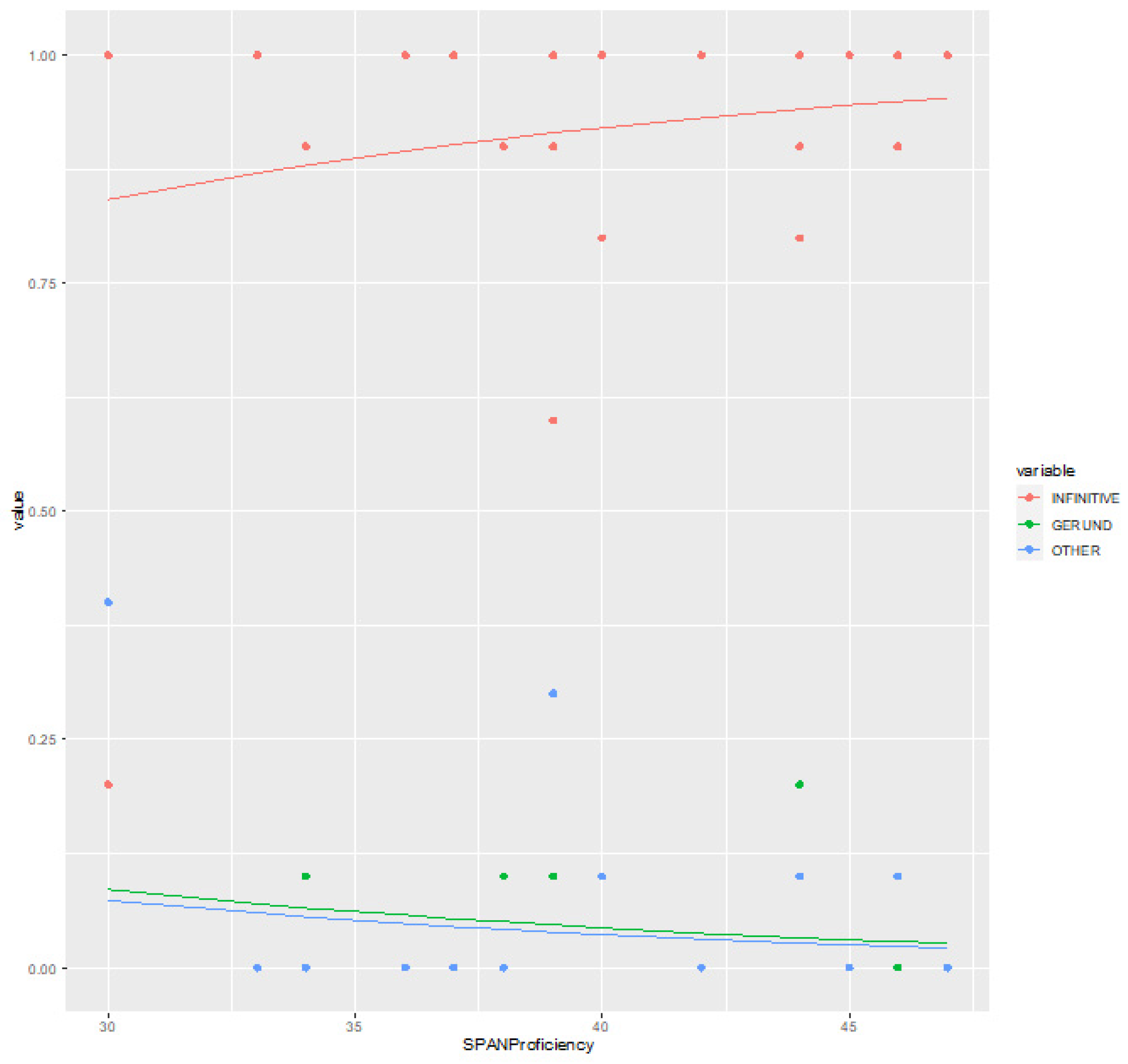

The model revealed interactions between proficiency, language experience, and participants responses.

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show that the more proficient the HS was in Spanish and the more Spanish usage and exposure the HS had, the higher the odds were to choose the infinitive compared to the alternative responses.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of this study was to examine heritage speakers’ knowledge of infinitives in subject position and as objects of a preposition. While in Spanish the use of the infinitive is required in these contexts, in English the gerund is the most frequent and acceptable form to be used. We tested heritage speakers’ productive and receptive knowledge via an elicited production task and a contextualized preference task.

Two research questions guided the study. The first research question investigated whether the Spanish heritage speakers had knowledge of infinitives as subjects of a clause and as objects of a preposition. We hypothesized that there would be a lower use of infinitives in both contexts due to crosslinguistic influence from English. The results from the EPT showed lower production of the infinitive among the heritage speakers. There was 76% production of the infinitive and 24% of the gerund and other ungrammatical forms. The SDS were categorical in their use of the infinitive and behaved at the ceiling. When the two conditions tested were examined, the results showed that the difficulties were found in the subject of the clause condition. In this condition, the heritage speakers overextended the gerund 35% of the time. In the object of a preposition condition, the overextension of the gerund was not as high as in the subject condition. It reached only 4% of usage. The results from CPT also showed differences among the heritage speakers and the SDS. Specifically, there was less preference for the infinitive among the heritage speakers (80%) and some preference for the gerund (18%). In this task, the results also showed a different behavior depending on the condition tested. More preference for the gerund was evidenced in the subject of the clause condition (28%) than in the object of the clause condition (7%). Overall, these results confirmed Hypothesis 1, as the heritage speakers overextended the gerund in contexts in which infinitives were expected. However, our data suggest that not all syntactic contexts were affected equally. The HSs overextend the gerund form significantly more in subject position in both production (35%) and interpretation (28%). These results suggest that the subject condition was conducive to greater use of the gerund, while the object of the preposition condition was not.

Quintero Ramírez (

2015) highlights that gerunds are found more frequently in these contexts. Thus, this morphosyntactic difference means that infinitive constructions in subject position are only possible but not obligatory or highly used in English. It is possible that infinitive use in subject position is more vulnerable to crosslinguistic influence given that gerund use in English often appears in subject position, which makes it a more frequently activated form. These results confirm previous studies with heritage speakers, in which gerund overextension was found in infinitive contexts.

Belpoliti and Bermejo (

2019), for instance, found instances in which the gerund was used as a complement of a preposition and in subject position in a corpus of written essays. The fact that the overextension of the gerund is more evident in the context of the subjects of a clause is consistent with

Escobar and Potowski (

2015). The authors found more acceptance of gerunds in subject positions than in other contexts.

The second research question focused on the role of language proficiency and linguistic experience. We hypothesize that both factors would impact the usage of infinitives among heritage speakers, with individuals exhibiting higher proficiency and stronger activation of Spanish relying on the infinitive to a greater extent. Conversely, those with lower proficiency and less use of the language were expected to display more variability in infinitive use and a higher incidence of gerund use and preference. Our findings corroborated the expectation that heritage speakers’ productive and receptive knowledge of infinitives is indeed influenced by their proficiency level and linguistic experience. The data demonstrated that participants with elevated proficiency and greater language exposure tended to use and prefer the infinitive more frequently. Conversely, participants with intermediate proficiency and limited Spanish usage and exposure displayed a higher tendency to use and prefer the gerund. These outcomes provide supporting evidence for Hypothesis 2 and align with

Putnam and Sánchez’s (

2013) Activation Approach. According to their model, the preservation of the heritage language is contingent upon the frequency of activation for both production and comprehension. Their model suggests that during the initial stage, the heritage language incorporates certain features from the L2 grammar, while in the subsequent stage, a significant reassembly of features occurs. This reassembly process, where L2 features are integrated into the phonetic form of the heritage language, is driven by distinct patterns of language activation, which have been operationalized as language experience and proficiency in our study. The fact that the divergences were observed in both production and interpretation suggests the possibility that, at least concerning the use of the gerund in subject position, this long-term alignment or association may have become ingrained within the grammatical representation, as proposed by recent work (

Perez-Cortes et al. 2019;

Putnam and Sánchez 2013;

Sánchez 2019). This is an important finding in the sense that it suggests that the difficulties heritage speakers of Spanish show in some grammatical domains involve changes in the internal grammatical representation. Future research would benefit from examining whether this particular property is also challenging for child heritage speakers of Spanish and whether growth is interrupted or vulnerable to child L1 attrition in the lifespan.

In conclusion, this study has shown that infinitives are an active locus of variability in Spanish heritage grammars. Despite their overall production and preference for infinitives, the gerund is overextended in contexts in which the infinitive is required in Spanish. Specifically, there is overextension of the gerund when the infinitive is used as the subject of the clause. This evidence provides support for current theoretical premises in heritage language development, suggesting a strong correlation between heritage language activation and the reassembly of heritage language features (

Putnam and Sánchez 2013;

Sánchez 2019). Future research would benefit from testing other conditions to determine whether the variability observed in our data is also present in different syntactic contexts.