Indexing Deficiency: Connecting Language Learning and Teaching to Evaluations of US Spanish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Colonial Underpinnings of Language Separateness

Spanish Language Education in the United States

3. Evaluating Implicit Social Cognition and Linguistic Bias

4. Indexing Deficits

- Are US Spanish lexical features salient to groups that have different experiences with Spanish language learning, and what do they index in terms of perceived acquisition and academic-ness when juxtaposed with standardized Spanish lexical features?

- To what extent is differential participation in language education programs (L2 students, heritage students, and teachers) correlated with more positive explicit attitudes toward US Spanish features?

- Do the attitudes and associations elicited from indirect methods (i.e., the MGT) and automatic response (i.e., the IAT) indicate that explicit and implicit biases result from distinct cognitive processes?

5. The Present Study

5.1. Participant Recruitment

5.2. Stimuli and Design

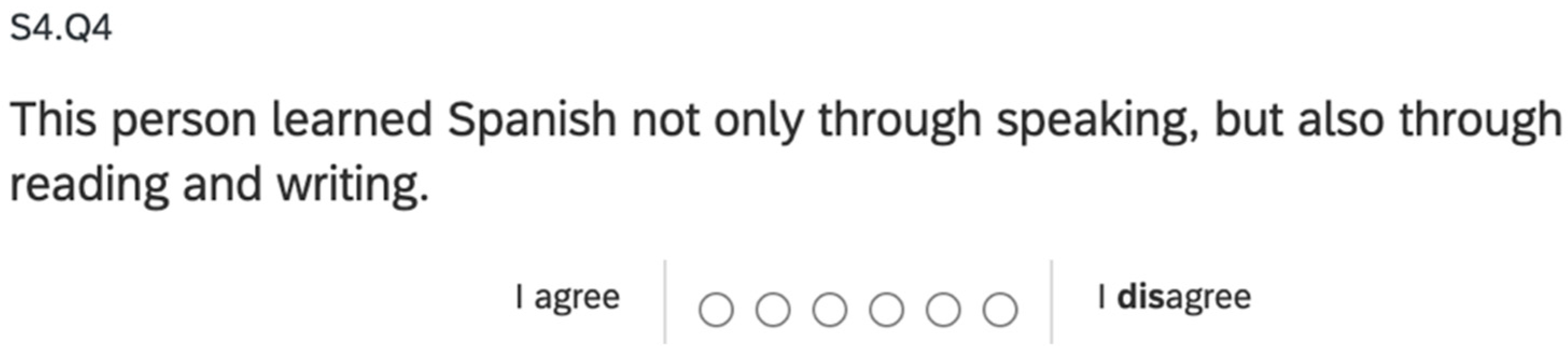

5.2.1. Experiment 1: Matched Guise Test

- This person speaks fluently.

- This person has not fully acquired their language.

- This person learned their language not only through speaking, but also through reading and writing.

- This person could communicate easily in a Spanish speaking country.

- This person is still learning their language.

- This person would be able to use their language in a professional environment.

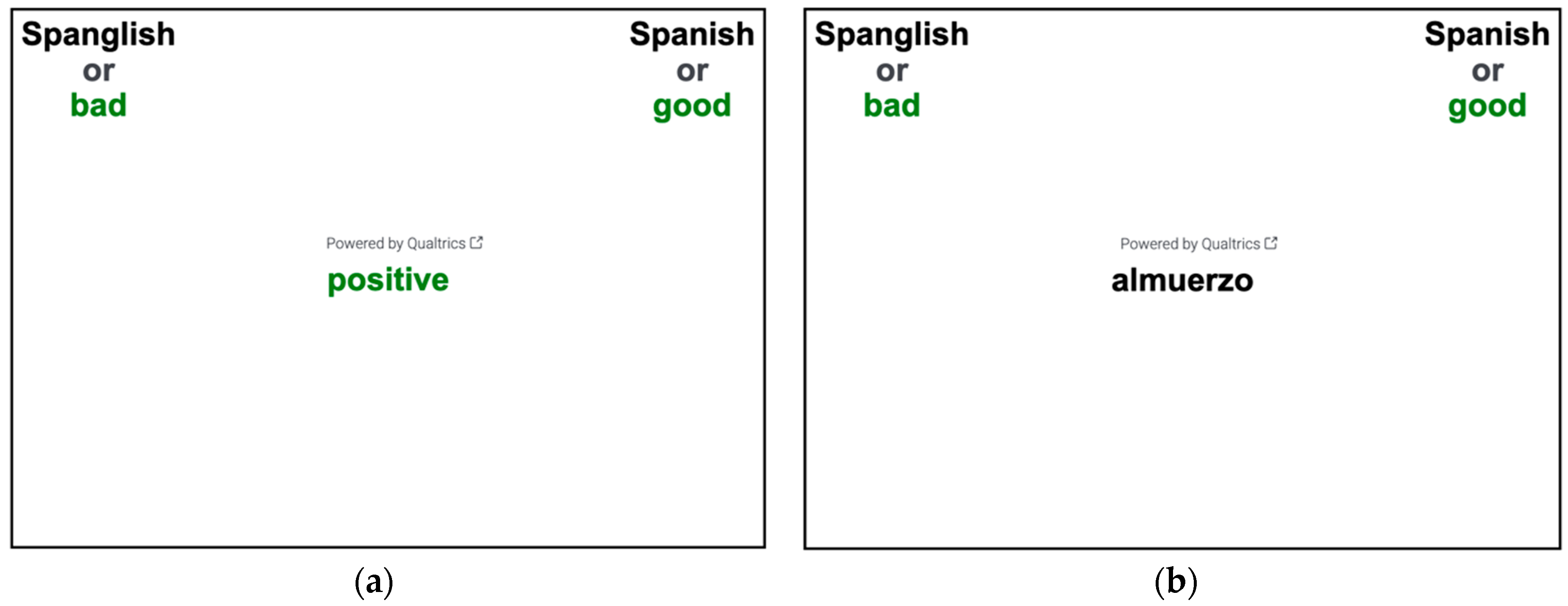

5.2.2. Study 2: Implicit Association Test

5.3. Statistical Models

6. Results

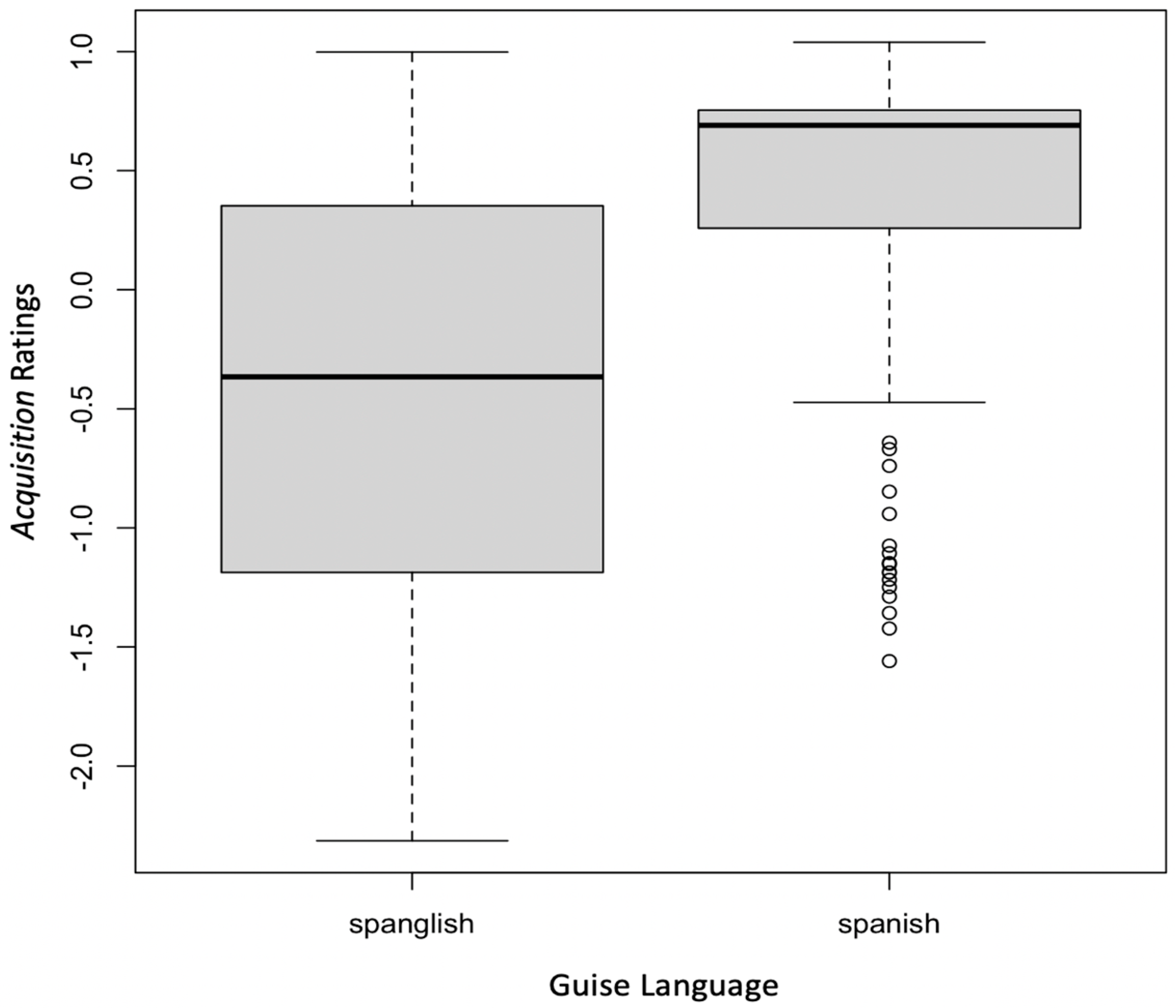

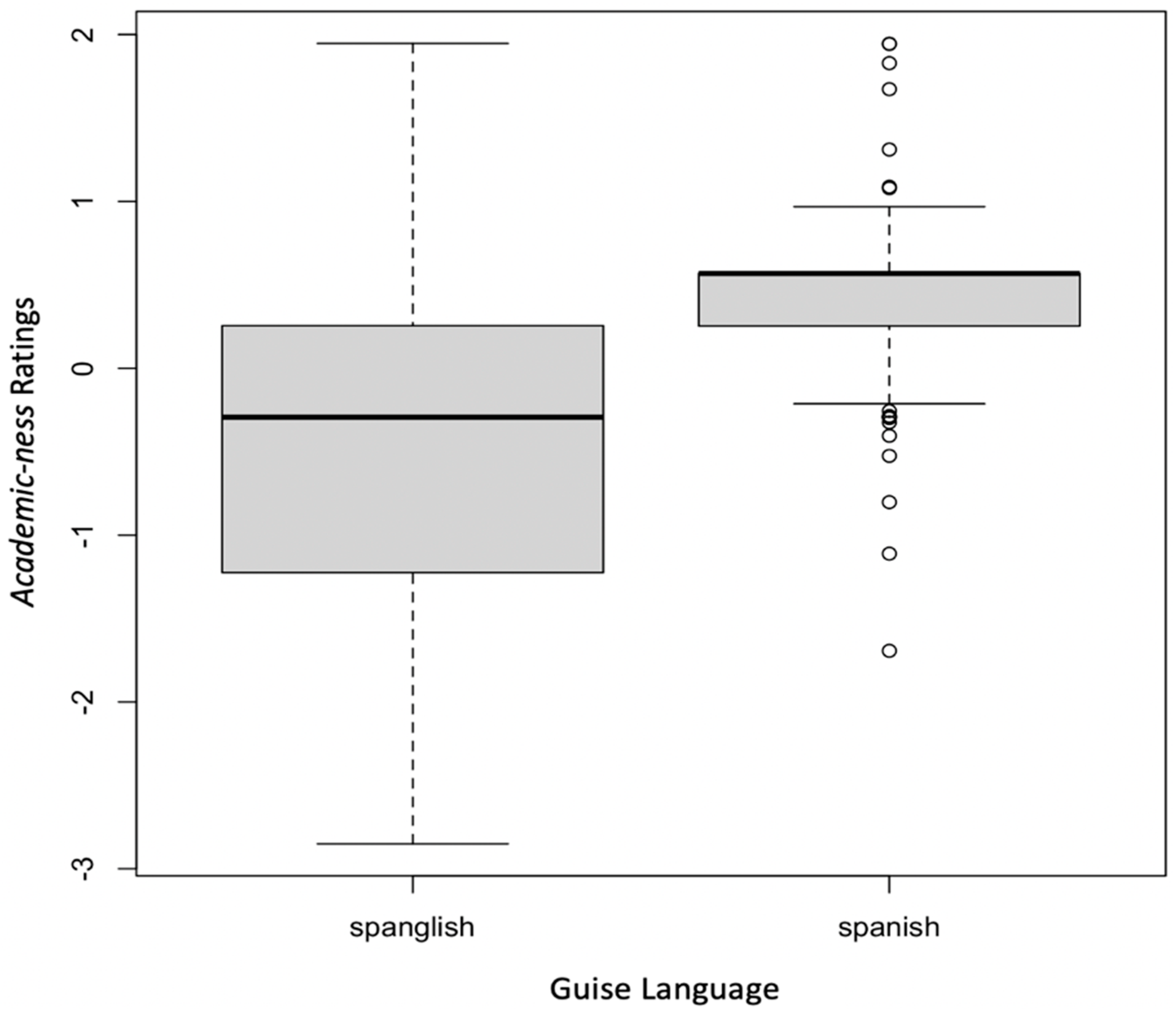

6.1. Eliciting Attitudes from the MGT

6.2. Assessing Implicit Bias

6.3. Correlation Analyses: MGT to IAT

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Guise Stories (English Words Bolded Refer to SS and Those Underlined Refer to USS)

| Standardized Spanish (SS) Repertoire | US Spanish (USS) Repertoire | English Translation | |

| Story A | Bueno, para ir al muelle, tienes que doblar a la derecha en la calle Retiro. Puedes dar vuelta en Pacheco, pero hay mucho tráfico ahí todo el tiempo. Ya sabes, es mejor evitar los semáforos. Te espero en la camioneta verde de mi papá. Bueno, nos vemos ahí. | So, para ir al pier, tienes que doblar a la derecha en Retiro Street. Puedes dar vuelta en Pacheco, pero hay mucho traffic ahí all the time. You know, es mejor evitar las traffic lights. Te espero en la troca verde de mi papá. Ok pues, nos vemos ahí. | Well/So, to go to the pier, you have to turn right on Retiro Street. You can turn on Pacheco, but there is a lot of traffic there all the time. You know, it’s better to avoid the traffic lights. I’ll be waiting for you in my dad’s green truck. Ok, see you then. |

| Story B | Para llegar a la tienda, tienes que tomar la carretera que va al centro. Sin embargo, habrá mucha gente porque es la hora del almuerzo. Todos irán a los restaurantes durante el descanso para comprar comida. Yo estoy lleno/a y no voy a comer, pero si quieres, podemos llegar al restaurante. | Para llegar a la tienda, tienes que subirte al freeway que va al downtown. Pero like, habrá mucha gente porque es la hora del lonche. Todos irán a los restaurantes durante el break para agarrar comida. Yo estoy full so no voy a comer, pero like, si quieres, podemos parar al restaurante. | To arrive at the store, you need to get on the freeway and go downtown. However/However or But like, there will be a lot of people because it’s lunch time. Everyone will be going to restaurants during break to get food. I’m full so I won’t be eating, however/but like, if you want, we can stop at the restaurant. |

| Story C | Pues para llegar al parque, debes dar vuelta a la izquierda en la calle Olivares. Puedes dejar el carro en la estructura de estacionamiento de la esquina, pero no sé si está abierta. De hecho, mejor pasa por la calle San Andrés y por ahí puedes entrar. Si prefieres, podemos hacer las compras para la fiesta en la tienda cerca de la parada. También, tengo que devolver unas cosas que ya no me sirven. | So, para llegar al parque, debes hacer una izquierda en Olivares Street. Puedes dejar el carro en el parking lot de la esquina, pero no sé si están abiertos. Actually, mejor pasa por la calle San Andrés y por ahí puedes entrar. Si prefieres, podemos hacer las compras para el party en la tienda cerca del bus. También, tengo que regresar unas cosas que ya no me sirven. | So, to get to the park, you need to turn left on Olivares Street. You can leave your car in the parking lot on the corner, but I don’t know if they are open. Actually, it’s better to pass through San Andrés Street and you can enter through there. If you want, we can shop for the party in the store near the bus stop. Also, I have to return some things that I don’t need anymore. |

| Story D | Bueno, la película empieza a las ocho. Si quieres comer antes, podemos ir al restaurante que está cerca. Pero, Daniel no puede entrar porque hay un bar y todavía está en la escuela secundaria. Nos reunimos enfrente del supermercado. Primero voy de compras con Elena, quien también quiere platicar sobre los planes para este fin de semana. Una cosa más: ¡no te olvides de los boletos de entrada! | So, la muvi empieza a las ocho. Si quieres comer antes, podemos ir al restaurán que está cerca. Pero like, Daniel no puede entrar porque hay un bar y todavía está en la high school. Nos reunimos enfrente de la marketa. Primero me voy shopping con Elena, quien también quiere discutir sobre los planes para este weekend. Una cosa más: ¡no te olvides de los tickets! | Well/So, the movie starts at eight. If you want to eat before, we can go to the restaurant that is nearby. But/However or But like, Daniel can’t go in because there’s a bar and he’s still in high school. Let’s meet in front of the market. First, I’ll go shopping with Elena, who also wants to discuss plans for this weekend. One more thing: don’t forget the tickets! |

| Story E | Pues, la ruta más rápida es por la Avenida Paloma. Pero quizás esté cerrada, así que puedes también pasar por la calle Francisco. Aunque tal vez llegues tarde—ya ves, siempre hay mucho tráfico y poco estacionamiento. Javier nos va a acompañar porque renunció a su trabajo y ya no tiene que trabajar por las noches. Cuando estés listo, ¡envíame un mensaje! | So pues, la ruta más rápida es por Paloma Avenue. Pero quizás estará cerrada, so puedes también pasar por la calle Francisco. Aunque tal vez estés tarde—you know, siempre hay mucho tráfico y poco parkin. Javier nos va a acompañar porque cuitió su trabajo y ya no tiene que trabajar en las noches. Cuando estés ready, ¡textéame! | So/So like, the fastest route is down Paloma Avenue. But maybe it will already be closed, so you can also go down Francisco Street. Even if you get there late—you know, there’s always a lot of traffic and little parking. Javier is going to accompany us because he quit his job and now, he doesn’t have to work at night. When you are ready, text me! |

| 1 | In this paper, and more broadly, I utilize languager to generally indicate any person that communicates and perceives language. I use speaker when the form of communication is specifically related to oral production and hearing. |

| 2 | In line with how Spanish language programs are often organized, heritage language learning encompasses classes for languagers who are raised in a home where a non-hegemonic language is used, and who can use or comprehend the home language to some degree, and who are, to any degree, bilingual in that language and in the hegemonic variety (Valdés et al. 1999). Second language (L2) learning refers to courses in which languagers are learning or have learned an additional language in school. With regard to this study, L2 learners began learning Spanish in school after the age of 14. |

| 3 | The generalized idealized communicator is a hearing subject (see Henner and Robinson 2021), thus colonial epistemologies also take phonocentric, ableist stances. |

| 4 | L1 variability within the teacher group did not significantly mediate bias differences. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | A six-point scale has been shown to increase discrimination and reliability than a five-point scale (Chomeya 2010). |

| 7 | An exploratory factor analysis is an unsupervised language model that requires human expertise in the analysis of factors. As some evaluative scales may score a loading factor above 0.4 for more than one factor, researcher judgment ultimately determines factor grouping. |

| 8 | The only statistical comparisons of relevance to my research questions are those concerned with whether or not each group of listeners differentiated each of the target language guises (SS/USS) by the attitudinal category, namely a main effect of the guise variety or an interaction effect between the guise variety and listener profile group. Accordingly, I limit my reporting and discussion of results to these effects and potential interactions. Any potential main effect of the listener profile group would reflect non-substantive comparisons of averaged acquisition or academic-ness ratings by group (i.e., there is no meaningful interpretation of one participant group having higher ratings over other groups unless those higher ratings interact with differentiated ratings mediated by the guise variety). |

| 9 | Errors were replaced with participant block means of correct trials plus 600 ms (or the D600 procedure; Greenwald et al. 2003). |

References

- Alonso, Lara, and Laura Villa. 2020. Latinxs’ Bilingualism at Work in the US: Profit for Whom? Language, Culture and Society 2: 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anya, Uju. 2020. African Americans in World Language Study: The Forged Path and Future Directions. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 40: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anya, Uju. 2021. Critical Race Pedagogy for More Effective and Inclusive World Language Teaching. Applied Linguistics 42: 1055–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, Tasha. 2022. Linguistic Imperialism: Countering Anti Black Racism in World Language Teacher Preparation. Journal for Multicultural Education 16: 246–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, Netta, Eric Johnson, Shirley Brice-Heath, Teresa McCarty, Elinor Ochs, Tamar Kremer-Sadlik, Susan Blum, Ana Celia Zentella, Jonathan Rosa, and Nelson Flores. 2015. Invited Forum: Bridging the ‘Language Gap’. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 25: 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, Molly. 2010. Dialect Divergence and Convergence in New Zealand English. Language in Society 39: 437–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Benjamin. 2012. Heteroglossia. In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism. Edited by M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge and A. Creese. London: Routledge, pp. 511–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, Mary, Dolores Inés Casillas, and Jin Sook Lee. 2018. California Latinx Youth as Agents of Sociolinguistic Justice. In Language and Social Justice in Practice. Edited by Eric J. Johnson, Jonathan Rosa, Laura R. Graham, Netta Avineri and Robin Conley. London: Routledge, pp. 166–75. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Katharine E. 2018. Marginalization of Local Varieties in the L2 Classroom: The Case of US Spanish. L2 Journal 10: 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamai, Silvia, and Fabio Ardolino. 2020. Italian with an Accent: The Case of ‘Chinese Italian’ in Tuscan High Schools. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 39: 132–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callesano, Salvatore, and Phillip M. Carter. 2022. Unidirectional Language Bias: The Implicit Association Test with Spanish and English in Miami. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13670069221121160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2009. The Nature of Sociolinguistic Perception. Language Variation and Change 21: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, Kathryn. 2010. Sociolinguistics and Perception. Language and Linguistics Compass 4: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Thomas P., Ruth Pogacar, Chris Pullig, Michal Kouril, Stephen Aguilar, Jordan LaBouff, Naomi Isenberg, and Alek Chakroff. 2019. Survey-Software Implicit Association Tests: A Methodological and Empirical Analysis. Behavior Research Methods 51: 2194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstens, Adelia. 2016. Translanguaging as a Vehicle for L2 Acquisition and L1 Development: Students’ Perceptions. Language Matters 47: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2016. On the Social Perception of Intervocalic/s/Voicing in Costa Rican Spanish. Language Variation and Change 28: 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2021a. Heritage Mexican Spanish Speakers’ Sociophonetic Perception of/s/Aspiration. Spanish as a Heritage Language 1: 167–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Whitney. 2021b. Mexicans’ and Mexican-Americans’ Perceptions of Themselves and Each Other: Attitudes toward Language and Community. In Topics in Spanish Linguistic Perceptions. Edited by Luis Alfredo Ortiz-López and Eva-María Suárez Büdenbender. London: Routledge, pp. 138–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, Whitney, and Matthew Kanwit. 2022. Do Learners Connect Sociophonetic Variation with Regional and Social Characteristics?: The Case of L2 Perception of Spanish Aspiration. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 44: 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Moreno, Laura C. 2021. The Problem with Latinx as a Racial Construct Vis-à-Vis Language and Bilingualism: Toward Recognizing Multiple Colonialisms in the Racialization of Latinidad. In Handbook of Latinos and Education. Edited by Enrique G. Murillo Jr., Dolores Delgado Bernal, Socorro Morales, Luis Urrieta Jr., Eric Ruiz Bybee, Juan Sánchez Muñoz, Victor B. Saenz, Daniel Villanueva, Margarita Machado-Casas and Katherine Espinoza. London: Routledge, pp. 164–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chomeya, Rungson. 2010. Quality of Psychology Test Between Likert Scale 5 and 6 Points. Journal of Social Sciences 6: 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioè-Peña, María. 2022. The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s school: Interrogating settler colonial logics in language education. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 42: 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, Justin T., Kelly E. Wright, Rachel Elizabeth Weissler, and Robin M Queen. 2020. Language and Discrimination: Generating Meaning, Perceiving Identities, and Discriminating Outcomes. Annual Review of Linguistics 6: 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, Tony. 2003. Standard English and the Politics of Language. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- de los Heros, Susana. 2009. Linguistic Pluralism or Prescriptivism? A CDA of Language Ideologies in Talento, Peru’s Official Textbook for the First-Year of High School. Linguistics and Education 20: 172–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos, Cati V., Kate Seltzer, and Arturo Molina. 2021. ‘Juntos Somos Fuertes’: Writing Participatory Corridos of Solidarity through a Critical Translingual Approach. Applied Linguistics 42: 1070–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drager, Katie, and M. Joelle Kirtley. 2016. Awareness, Salience, and Stereotypes in Exemplar-Based Models of Speech Production and Perception. In Awareness and Control in Sociolinguistic Research. Edited by Anna M. Babel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2008. Variation and the Indexical Field. Journal of Sociolinguistics 12: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, Lucila D., Patricia Sánchez, and Patricia D. Quijada Cerecer. 2013. Linguistic Violence, Insecurity, and Work: Language Ideologies of Latina/o Bilingual Teacher Candidates in Texas. International Multilingual Research Journal 7: 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, James D. 1996. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Pacific Grove: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jonathan St. B. T. 2008. Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 59: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, Russell H., and Michael A. Olson. 2003. Implicit Measures in Social Cognition Research: Their Meaning and Use. Annual Review of Psychology 54: 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Nelson. 2020a. From Academic Language to Language Architecture: Challenging Raciolinguistic Ideologies in Research and Practice. Theory into Practice 59: 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Nelson. 2020b. @nelsonlflores. Translanguaging Does Not Mean Using Multiple Named Languages in One Utterance. If You Define It That Way Just Stick with Code-Switching. It is, Instead, a Perspective That Prioritizes the Meaning-Making of Bi/Multilinguals in Ways That Challenge Normative Language Ideologies. Twitter. January 24. Available online: https://twitter.com/nelsonlflores/status/1220857637073494027?s=20 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. 2022. Undoing Competence: Coloniality, Homogeneity, and the Overrepresentation of Whiteness in Applied Linguistics. Language Learning. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Nelson, Tatyana Kleyn, and Kate Menken. 2015. Looking Holistically in a Climate of Partiality: Identities of Students Labeled Long-Term English Language Learners. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 14: 113–32. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nelson, Mark C. Lewis, and Jennifer Phuong. 2018. Raciolinguistic Chronotopes and the Education of Latinx Students: Resistance and Anxiety in a Bilingual School. Language & Communication 62: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Susan, and Judith T Irvine. 2019. Signs of Difference: Language and Ideology in Social Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2011. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2019. Decolonizing Foreign, Second, Heritage, and First Languages. In Decolonizing Foreign Language Education: The Misteaching of English and Other Colonial Languages. Edited by Donaldo Macedo. New York: Routledge, pp. 152–68. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Ricardo Otheguy. 2020. Plurilingualism and Translanguaging: Commonalities and Divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23: 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia, Nelson Flores, Kate Seltzer, Li Wei, Ricardo Otheguy, and Jonathan Rosa. 2021. Rejecting Abyssal Thinking in the Language and Education of Racialized Bilinguals: A Manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 18: 203–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Peter. 2001. Language Attitudes and Sociolinguistics. Journal of Sociolinguistics 5: 626–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, Anthony G., and Brian A. Nosek. 2009. Attitudinal Dissociation: What Does It Mean? In Attitudes: Insights from The New Implicit Measures. Edited by R. E. Petty, R. H. Fazio and P. Brinol. Hove: Psychology Press, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, Anthony G., Debbie E. McGhee, and Jordan L. K. Schwartz. 1998. Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 1464–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, Anthony G., Brian A. Nosek, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2003. Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: I. An Improved Scoring Algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, Jennifer, and Katie Drager. 2010. Stuffed Toys and Speech Perception. Linguistics 48: 865–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Monica. 2006. Linguistic Minorities and Modernity: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography, 2nd ed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, Annie. 2020. Machine Learning for Linguistics: Exploratory Factor Analysis [Computer Software]. Available online: https://github.com/anniehelms/machine_learning_for_linguistics (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Henner, Jon, and Octavian Robinson. 2021. Unsettling Languages, Unruly Bodyminds: Imaging a Crip Linguistics. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/7bzaw/ (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Holguín Mendoza, Claudia. 2018. Critical Language Awareness (CLA) for Spanish Heritage Language Programs: Implementing a Complete Curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal 12: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianos, Maria Adelina, Andrei Rusu, Ángel Huguet, and Cecilio Lapresta-Rey. 2020. Implicit Language Attitudes in Catalonia (Spain): Investigating Preferences for Catalan or Spanish Using the Implicit Association Test. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 44: 214–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Miyako. 2003. The Listening Subject of Japanese Modernity and His Auditory Double: Citing, Sighting, and Siting the Modern Japanese Woman. Cultural Anthropology 18: 156–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Miyako. 2006. Vicarious Language: Gender and Linguistic Modernity in Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Okim, and Donald L. Rubin. 2009. Reverse Linguistic Stereotyping: Measuring the Effect of Listener Expectations on Speech Evaluation. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 28: 441–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpen, Samuel C., Lile Jia, and Robert J. Rydell. 2012. Discrepancies between Implicit and Explicit Attitude Measures as an Indicator of Attitude Strength. European Journal of Social Psychology 42: 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, Ruth. 2016. The Matched-Guise Technique. In Research Methods in Intercultural Communication. Edited by Zhu Hua. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff, and Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Wallace E., Hannah Frankle, and G. Richard Tucker. 1966. Judging Personality through Speech: A French-canadian Example. Journal of Communication 16: 305–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, Kristin A., Mahzarin R. Banaji, Brian A. Nosek, and Anthony G. Greenwald. 2007. Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: IV: What We Know (so Far) about the Method. In Implicit Measures of Attitudes. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Licata, Gabriella, Tasha Austin, and Aris Moreno Clemons. Forthcoming. Raciolinguistics and Spanish language teaching. Edited by Mara Fuertes Gutiérrez, Rosina Márquez-Reiter, Ben Evans, Aris Moreno Clemons. Decolonizing Spanish Language Teaching and Social Justice: Theoretical Approaches, Teaching Competences and Practices. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching.

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2012. English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Loza, Sergio. 2017. Transgressing Standard Language Ideologies in the Spanish Heritage Language (SHL) Classroom. Chiricù Journal: Latina/o Literature, Art, and Culture 1: 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Rosina. 2018. An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn A. 2003. Perceptions of Dialect in a Changing Society: Folk Linguistics along the Texas-Mexico Border. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Ramón Antonio, and Alexander Feliciano Mejía. 2020. Looking Closely and Listening Carefully: A Sociocultural Approach to Understanding the Complexity of Latina/o/x Students’ Everyday Language. Theory into Practice 59: 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Jones, Marilyn, and Suzanne Romaine. 1986. Semilingualism: A Half-Baked Theory of Communicative Competence. Applied Linguistics 7: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Robert M., and Erin Carrie. 2018. Implicit–Explicit Attitudinal Discrepancy and the Investigation of Language Attitude Change in Progress. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39: 830–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Robert M., and Alexander Gilmore. 2017. ‘The People Who Are out of ‘Right’E Nglish’: J Apanese University Students’ Social Evaluations of E Nglish Language Diversity and the Internationalisation of Japanese Higher Education. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 27: 152–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Robert M., and Andrew McNeill. 2022. Implicit and Explicit Language Attitudes: Mapping Linguistic Prejudice and Attitude Change in England. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, Mike. 2022. The Language-Elsewhere: A Friendlier Linguistic Terrorism. In The Spanish Language in the United States. Edited by José A. Cobas, Bonnie Urciuoli, Joe Feagin and Daniel J. Delgado. London: Routledge, pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Scotton, Carol. 1997. Codeswitching. In The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Edited by Florian Coulmas. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, and Nancy Stern. 2011. On so-called Spanglish. International Journal of Bilingualism 15: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García, and Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying Translanguaging and Deconstructing Named Languages: A Perspective from Linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, Lillie, and Rosti Vana. 2022. The ‘Other’ Latinx: The (Non) Existent Representation of Afro-Latinx in Spanish Language Textbooks. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantos, Andrew J., and Andrew W. Perkins. 2013. Measuring Implicit and Explicit Attitudes toward Foreign Accented Speech. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 32: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, Richard E., Pablo Briñol, Chris Loersch, and Michael J. McCaslin. 2009. The Need for Cognition. In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes i’ll Start a Sentence in Spanish y Termino En Espanol: Toward a Typology of Code-Switching1. Linguistics 18: 581–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, Josh. 2019. Exploring the Role of Translanguaging in Linguistic Ideological and Attitudinal Reconfigurations in the Spanish Classroom for Heritage Speakers. Classroom Discourse 10: 306–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Tracy. 2020. Critical Language Awareness and L2 Learners of Spanish: An Action-Research Study. Foreign Language Annals 53: 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, Anibal. 2000. Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. International Sociology 15: 215–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Rangel, Natalie, Verónica Loureiro-Rodríguez, and María Irene Moyna. 2015. ‘Is That What I Sound like When I Speak?’: Attitudes towards Spanish, English, and Code-Switching in Two Texas Border Towns. Spanish in Context 12: 177–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, Diego, Alberto Pastor, and Deni Basaraba. 2019. Internal Linguistic Discrimination: A Survey of Bilingual Teachers’ Language Attitudes toward Their Heritage Students’ Spanish. Bilingual Research Journal 42: 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, Jonathan. 2016. Standardization, Racialization, Languagelessness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies across Communicative Contexts. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 26: 162–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, Jonathan, and Nelson Flores. 2017. Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective. Language in Society 46: 621–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Laura, Dirk Speelman, and Dirk Geeraerts. 2019. The Relational Responding Task (RRT): A Novel Approach to Measuring Social Meaning of Language Variation. Linguistics Vanguard 5: 20180012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, Kate. 2022. Enacting a Critical Translingual Approach in Teacher Preparation: Disrupting Oppressive Language Ideologies and Fostering the Personal, Political, and Pedagogical Stances of Preservice Teachers of English. TESOL Journal 13: e649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, Kate, and Beth Wassell. 2022. Toward an Antiracist World Language Classroom: A Translanguaging Approach. In The Antiracist World Language Classroom. Edited by Cécile Accilien and Krishauna Hines-Gaither. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Michael. 2018. Monoglot ‘Standard’ in America: Standardization and Metaphors of Linguistic Hegemony. In The Matrix of Language. Edited by Donald Brenneis and Ronald K. S. Macaulay. New York: Routledge, pp. 284–306. [Google Scholar]

- Siordia, Celestina, and Kathy MinHye Kim. 2022. How Language Proficiency Standardized Assessments Inequitably Impact Latinx Long-term English Learners. TESOL Journal 13: e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís Obiols, Marina. 2002. The Matched Guise Technique: A Critical Approximation to a Classic Test for Formal Measurement of Language Attitudes. Noves SL.: Revista de Sociolingüística 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Solorzano, Daniel G., and Tara J. Yosso. 2001. Critical Race and LatCrit Theory and Method: Counter-Storytelling. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 14: 471–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukup, Barbara. 2013. On Matching Speaker (Dis) Guises–Revisiting a Methodological Tradition. In Language (De) Standardisation in Late Modern Europe: Experimental Studies. Edited by Tore Kristiansen and Stefan Grondelaers. Oslo: Novus, pp. 267–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanowitsch, Anatol. 2005. The Matched Guise Technique. Empirical Methods in Linguistics, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Dongyun. 2014. From Communicative Competence to Interactional Competence: A New Outlook to the Teaching of Spoken English. Journal of Language Teaching & Research 5: 1062–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga, Meredith. 2017. Matched Guise Effects Can Be Robust to Speech Style. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 142: EL18–EL23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, Robert. 2003. The (Non) Native Standard Language in Foreign Language Education: A Critical Perspective. In The Sociolinguistics of Foreign Language Classrooms: Contributions of the Native, the near-Native and the Non-Native Speaker. Edited by Carl Blyth. Boston: Thomson Place, pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Train, Robert. 2007. ‘Real Spanish:’ Historical Perspectives on the Ideological Construction of a (Foreign) Language. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 4: 207–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, Robert. 2020. Contesting Regimes of Variation: Critical Groundwork for Pedagogies of Mobile Experience and Restorative Justice. Critical Multilingualism Studies 8: 251–300. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2004. Between Support and Marginalisation: The Development of Academic Language in Linguistic Minority Children. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 7: 102–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdé s, Guadalupe, J. Peyton, J. Ranard, and S. McGinnis. 1999. Heritage language students: Profiles and possibilities. Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource, 37–80. [Google Scholar]

- Van Compernolle, Remi A., and Lawrence Williams. 2012. Reconceptualizing Sociolinguistic Competence as Mediated Action: Identity, Meaning-making, Agency. The Modern Language Journal 96: 234–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vana, Rosti Frank. 2020. Learning with an Attitude?!: Heritage and L2 Students’ Language Attitudes toward Spanish Language Varieties in the Advanced Mixed Class. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2408544341/abstract/FA3BAFAB5A5242B5PQ/1 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- VanPatten, Bill. 2015. ‘Hispania’ White Paper: Where Are the Experts? Hispania 98: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserscheidt, Philipp. 2021. A Usage-Based Approach to ‘Language’ in Language Contact. Applied Linguistics Review 12: 279–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherholtz, Kodi, Kathryn Campbell-Kibler, and T. Florian Jaeger. 2014. Socially mediated syntactic alignment. Language Variation and Change 26: 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n = 81 | Gender Identification | Age Range | Birthplace | L1 Spanish | Mean Years of Spanish Language Learning in School |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage n = 28 | Female: 16 Male: 9 Nonbinary: 2 Gender fluid: 1 | 18–25 = 16 26–35 = 9 36–45 = 2 46–55 = 1 | Argentina: 1 Cuba: 1 Guatemala: 2 Mexico: 1 Puerto Rico: 1 USA: 22 | Yes: 28 No: 0 | 7.2 |

| L2 n = 30 | Female: 19 Male: 8 Nonbinary: 2 Fluid feminine: 1 | 18–25 = 13 26–35 = 6 36–45 = 6 46–55 = 2 56–60 = 3 | Romania: 1 South Korea: 1 USA: 28 | Yes: 0 No: 30 | 6.2 |

| Teacher n = 23 | Female: 17 Male: 6 | 18–25 = 1 26–35 = 8 36–45 = 8 46–55 = 5 56–60 = 1 | Italy: 1 Mexico: 1 Peru: 1 Spain: 2 USA: 18 | Yes: 11 No: 12 | 7.6 |

| IAT# | Names | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|

| #1, #2 | Spanish | sin embargo (‘however’), la camioneta (‘truck’), el almuerzo (‘lunch’), alquilar (‘to rent’), las facturas (‘bills’) |

| #1, #2 | Spanglish | pero like (‘however’), la troca (‘truck’), el lonche (‘lunch’), rentar (‘to rent’), los biles (‘bills’) |

| #1 | Academic | books, tests, school, formal, scholar |

| #1 | Not Academic | slang, informal, street, uneducated, illiterate |

| #2 | Complete | entire, full, intact, whole, perfect |

| #2 | Not Complete | deficient, lacking, fragmented, imperfect, partial |

| Rating Scale | Factor 1: Acquisition | Factor 2: Academic-Ness |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. Is fluent | 0.7 | 0.49 |

| Q2. Incomplete acquisition | 0.84 | 0.26 |

| Q3. Learned by speaking, reading, and writing | 0.22 | 0.55 |

| Q4. Speaks ‘globally understood’ language | 0.6 | 0.51 |

| Q5. Done learning language | 0.59 | 0.24 |

| Q6. Learned language in school | 0.56 | 0.77 |

| β Coefficient | Standard Error | t | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | –0.592 | 0.111 | 5.314 | 0.0001 |

| Participant—L2 | 0.322 | 0.155 | 2.082 | 0.03 |

| Participant—Teacher | 0.229 | 0.166 | 1.381 | 0.2 |

| Guise Language—SS | 0.885 | 0.127 | 6.974 | 0.0001 |

| β Coefficient | Standard Error | t | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.591 | 0.1052 | –5.615 | 0.0001 |

| Participant—L2 | 0.213 | 0.146 | 1.454 | 0.148 |

| Participant—Teacher | 0.287 | 0.157 | 1.834 | 0.06 |

| Guise Language—SS | 1.0241 | 0.121 | 8.48 | 0.0001 |

| Participants, n | D Score Mean | t-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage, 28 | 0.51 | 10.39 | 0.00001 |

| L2, 30 | 0.35 | 4.1 | 0.0003 |

| Teacher, 22 | 0.49 | 4.32 | 0.0003 |

| Participants, n | D-Score Mean | t-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage, 28 | 0.63 | 9.43 | 0.00001 |

| L2, 30 | 0.54 | 7.29 | 0.00001 |

| Teacher, 22 | 0.58 | 7.27 | 0.00001 |

| Spanish | US Spanish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results | Acquisition (MGT) | Academic-ness (MGT) | Acquisition (MGT) | Academic-ness (MGT) | |

| Heritage learners | Spanish + Good (IAT) | r = 0.37 p < 0.004 | r = 0.16 p < 0.25 | r = −0.13 p < 0.34 | r = −0.02 p < 0.86 |

| Spanish + Academic (IAT) | r = 0.13 p < 0.34 | r = 0.8 p < −0.03 | r = −0.03 p < 0.83 | r = −0.16 p < 0.25 | |

| L2 learners | Spanish + Good (IAT) | r = 0.09 p < 0.5 | r = −0.06 p < 0.62 | r = 0.18 p < 0.15 | r = −0.36 p < 0.003 |

| Spanish + Academic (IAT) | r = 0.11 p < 0.41 | r = −0.36 p < 0.005 | r = −0.06 p < 0.66 | r = −0.06 p < 0.62 | |

| Teachers | Spanish + Good (IAT) | r = 0.05 p < 0.75 | r = −0.06 p < 0.69 | r = −0.23 p < 0.12 | r = −0.17 p < 0.27 |

| Spanish + Academic (IAT) | r = 0.37 p < 0.01 | r = 0.21 p < 0.18 | r = −0.25 p < 0.09 | r = −0.34 p < 0.02 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Licata, G. Indexing Deficiency: Connecting Language Learning and Teaching to Evaluations of US Spanish. Languages 2023, 8, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030204

Licata G. Indexing Deficiency: Connecting Language Learning and Teaching to Evaluations of US Spanish. Languages. 2023; 8(3):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030204

Chicago/Turabian StyleLicata, Gabriella. 2023. "Indexing Deficiency: Connecting Language Learning and Teaching to Evaluations of US Spanish" Languages 8, no. 3: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030204

APA StyleLicata, G. (2023). Indexing Deficiency: Connecting Language Learning and Teaching to Evaluations of US Spanish. Languages, 8(3), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030204