1. Introduction

Language and culture are mutually dependent spheres that conform integral facets of the human experience. Linguists, such as

Kramsch (

1998), deepened our understanding of the bounds between these two concepts and explored the importance of culture in foreign language teaching (

Kramsch 2017). If we bear the mutual dependency of language and culture in mind, it becomes apparent that teaching a language invariably involves teaching its culture (

Larrea-Espinar and Raigón-Rodríguez 2019). Teaching a language and its culture may be challenging (

Rodríguez Arancón 2023). With respect to this, the history of language teaching methods revealed that culture teaching and the development of intercultural competence received scant attention until the second half of the 20th century, which was a decisive historical moment in this regard (

Gómez Parra 2021). Pertaining to this, it is of uttermost importance to highlight the contributions by Michael Byram (

Byram 1993;

Jurasek and Byram 1995;

Prevos et al. 1992) at the turn of the millennium, as they undoubtedly paved a path towards the rigorous integration of culture teaching and the development of the intercultural competence in contemporary language teaching methods and approaches.

In connection with the topic of language teaching methods and approaches, it is of paramount importance to delve into the role of CLIL, which stands for content and language integrated learning. The very roots of bilingual programs such as CLIL were found in a sociolinguistic conflict that took place in Canada towards the conclusion of the 20th century, when the Canadian French-speaking community became dramatically concerned about the nuanced imposition of the English language in the public sphere (

Chacón-Beltran 2021). This situation led to the adoption of a series of language policy measures that were effectively applied when the government enacted the Official Languages Act in 1969 in order to guarantee language rights for both the English-speaking and French-speaking communities. Consequently, immersion programs were implemented in schools, offering part of the syllabus in both English and French in a balanced manner (

Chacón-Beltran 2021). This immersion model is at the very origin of what we nowadays know as content-based approaches (CBA) (

Tinedo-Rodríguez 2022). These language teaching approaches aim at integrating content from different subjects into language teaching. In other words, it consists of the acquisition of language skills while learning a specific disciplinary content. The pedagogical bases of these approaches lie on the fact that teaching language in context is more meaningful and effective (

Coyle and Holmes 2009;

Gómez Parra 2021;

Talaván and Tinedo-Rodríguez 2023).

In Europe, the most widespread CBA is CLIL, and authors such as

Coyle (

2006,

2008) and

Marsh (

2002) have played a significant role in the development and implementation of CLIL. CLIL is a clear proposal of an integrated curriculum (

Coyle and Holmes 2009) with a very particular way of understanding lesson planning, because in CLIL, there are four main axes: cognition, (inter)culture, content, and communication (

Coyle 2008). One of the main advantages of CLIL is its flexibility, as it allows the use of both the L1 and the L2 in the language learning process without rigid constraints. In this aspect, it is worth highlighting that the role of translanguaging (

Cenoz 2019) within CLIL contexts deserves special attention, as it allows to switch the code at the learners’ convenience, fostering the use of their entire linguistic repertoire (L1 and L2) (

Couto-Cantero and Fraga-Castrillón 2023). There are even specific adaptions of CLIL to infant education, such as the proposal by

Couto-Cantero and Ellison (

2022), titled InfanCLIL, or PETaL (Play, Education, Toys, and Languages), which is a proposal for early childhood education coined by

Gómez-Parra (

2021). Additionally, CLIL shows a high degree of complementarity with other emerging disciplines such as Didactic Audiovisual Translation (

Fernández-Costales 2017,

2021;

Talaván and Tinedo-Rodríguez 2023;

Tinedo-Rodríguez and Ogea-Pozo 2023), which proves its potential to adapt to future educational scenarios.

The pervasiveness of bilingual programs and the unprecedented quickness in their implementation in Spain require a comprehensive analysis to explore the current state of bilingual programs in Spain and the outcomes of the way in which they were implemented.

Alonso-Belmonte and Fernández-Agüero (

2021) addressed the issue of resistance to bilingual programs, delving into the reasons why teachers opposed the implementation of these programs by distinguishing five main axes: the effectiveness of the programs, the teaching experience, possible inequalities derived from the implementation of the programs, opportunities for career development, and hierarchies amongst professionals. Concerning this topic, research conducted by

Fernández-Sanjurjo et al. (

2019) holds significant importance. The authors discovered that elementary education students in CLIL programs performed slightly below non-CLIL students when their science knowledge was assessed. This means that non-CLIL students scored higher in science content assessments conducted in their L1. The sample consisted of 709 students from a Spanish monolingual region. At the other side of the spectrum, there are longitudinal studies, such as the one conducted by

Serra (

2007) in Switzerland, which showed that CLIL students performed better than non-CLIL students. There are also studies such as the one conducted by

Admiraal et al. (

2006) in the Netherlands that showed that there were no statistically significant differences between CLIL and non-CLIL students. In this rich scenario, it is worth taking the reflections of

Cenoz (

2013) because the author expressed that language teachers tended to approve the CLIL approach, whilst the same did not happen when it came to content teachers. The author explored the effects on language learning but did not fully agree with

Marsh (

2008) since

Marsh (

2008) stated that learning a concept in an L2 may develop High-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS), but

Cenoz (

2013) did not find a reason that justified that the development of HOTS (as conceived by

Blyth et al. (

1966)) could not take place in a non-bilingual setting. With regards to this matter,

Pérez Cañado (

2020) longitudinally examined

Cenoz (

2013) hypotheses, due to the fact that her research showed that students taking part in bilingual programs performed much better than the ones enrolled in non-bilingual programs in the use of English, vocabulary, oral reception, written reception, oral production, grammatical accuracy, lexical range, fluency, interaction, pronunciation, and task fulfilment. However, this study had a limitation when it came to assessing the equilibrium between content and language because it did not put the focus on content.

Even though the studies on culture learning and intercultural learning are still scarce for the Spanish case,

Gómez-Parra (

2020) shed some light by identifying the factors that students consider crucial for intercultural learning (IL): contact with peers through international exchanges, and the opportunity of having contact with native language assistants. Former studies, such as the one conducted by

Rodríguez Navarro et al. (

2011), analyzed different initiatives that were taking place in Spanish schools to include intercultural education in their programs, and the authors categorized these actions into seven different areas: welcome plans for foreign students, the importance of language and culture attention, the need to provide teachers with specific classroom management strategies, the intersection between intercultural education and mediation, the implication of the community, teachers’ training, and observatories. Nonetheless, these pioneering studies from the first decade of the 21st century focused on interculturality, particularly regarding the integration of migrant students into Spanish schools, but the intercultural competence should go beyond, as

Osuna-Rodríguez and Rodríguez-Osuna (

2017) affirmed. For these authors (

Osuna-Rodríguez and Rodríguez-Osuna 2017), intercultural competence is a need for 21st century citizens that is linked to the exponential technological growth that has fostered mobility and connectivity among people worldwide. In this context, exploring effective practices in bilingual education is of paramount importance, as

Aguado Odina (

2013) affirmed in a study in which she developed useful instruments to assess successful practices in bilingual and intercultural education. More recent and comprehensive studies, such as the ones compiled by

Lasagabaster and Doiz (

2016), went a step further, exploring the role of CLIL in the content and language learning processes and putting a special emphasis on interculture.

As has been formerly mentioned, language teaching methods and approaches are context dependent. In the Spanish context, a recent legislative change in education has taken place with the enactment of the new Education Act in 2020. The current education act put the focus on a competence-based approach (

Esteban and Cantero 2022). This new educational law has humanistic roots (

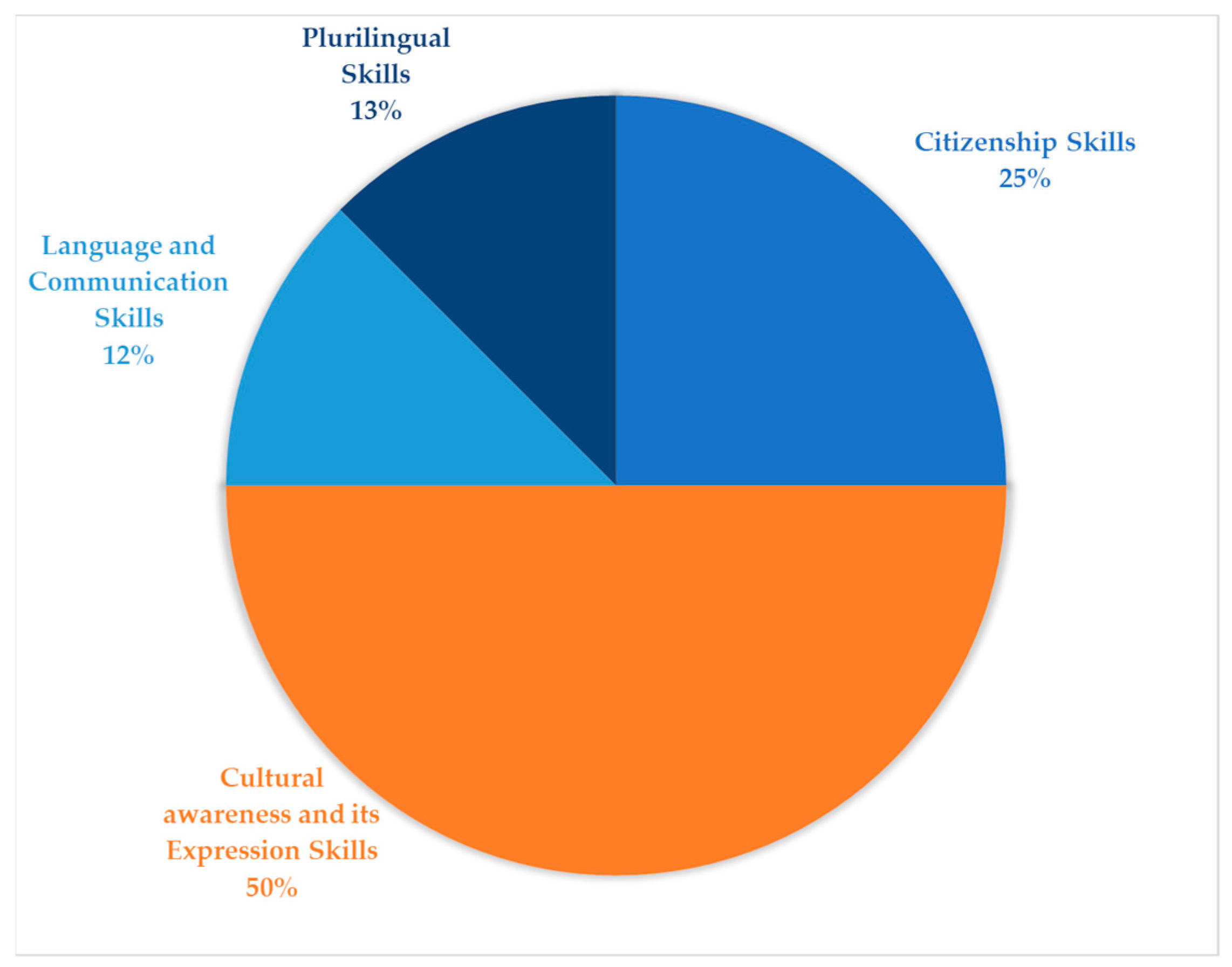

López Rupérez 2022), and a brief analysis of its key competences led to the conclusion that these competences are linked to the development of intercultural awareness, culture learning, and language acquisition. The key competences according to the law (R.D. 157/2022, p. 9) are language and communication skills, plurilingual skills, STEM skills, ICT skills, personal growth and autonomous learning skills, citizenship skills, entrepreneurship skills, and cultural awareness and expression skills. The law contains a total of 34 descriptors for elementary education, and eight of them (23.53%) are directly linked to bilingual and intercultural learning (BIE, hereinafter), as

Figure 1 shows.

Taking this legislative framework in mind, it is important to explore the contribution of CLIL towards the acquisition of all the LOMLOE competences that contain a BIE-based descriptor: language and communication skills, plurilingual skills, citizenship skills, and cultural awareness and its expression skills. Former studies have explored the contribution of CLIL towards the acquisition of language skills (e.g.,

Pérez Cañado and Lancaster 2017;

del Puerto and Lacabex 2013). This study aimed at exploring the relationship between CLIL programs and language learning and acquisition, as well as culture learning and the development of intercultural awareness. This was conducted through the analysis of BIE-based descriptors from the current Education Act, which are linked to IL.

3. Results and Discussion

The very nature of this research was quantitative, and as it has already been mentioned, the outcomes are showcased within the framework of three main axes that correspond to RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3. The data were analyzed with two statistical packages, JASP 0.16.4.0 and SPSS 27.

3.1. Students’ Insights on the Acquisition of the Intercultural Competence, and Culture and Language Learning in CLIL Programmes

In order to study the perception of students on their development of both culture learning and the intercultural competence in CLIL programs, the instrument that has been implemented departed from all the indicators of the key competences linked to culture and language learning and interculturality in the Spanish education system. Therefore, these results correspond to the cultural and language components of the following key competences of the Education Act (LOMLOE (Ley Orgánica de Modificación de la Ley Orgánica de Educación enacted in 2006)): competence in communication and language (CCL), plurilingual competence (PC), citizenship competence (CC), cultural awareness and cultural expression competencies (CACEC), and the personal, social, and learning-to-learn competence (PSLLC).

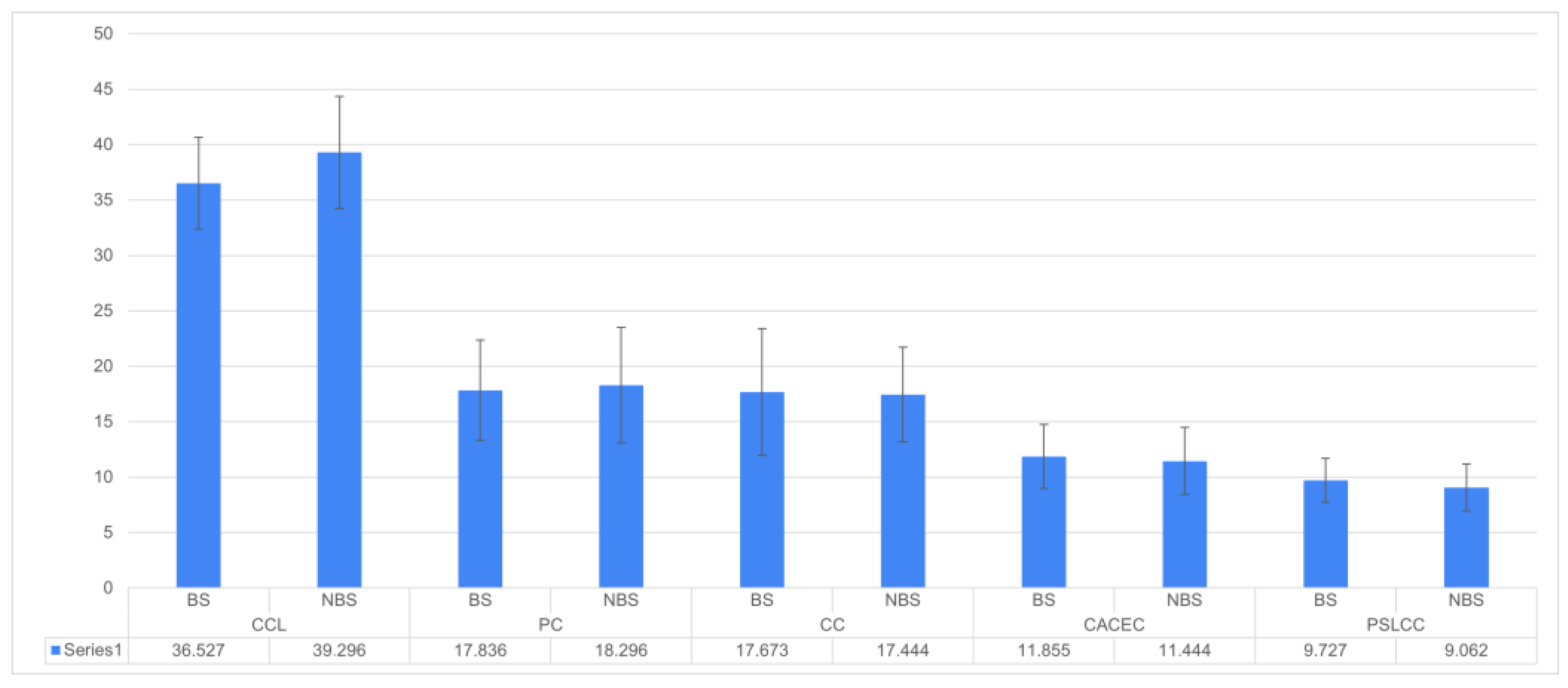

Apart from the descriptive data shown in

Figure 2, an inferential analysis was conducted to determine whether the differences between bilingual and non-bilingual schools are statistically significant. Therefore, a

t-test was performed on the collected data, obtaining the results shown in

Table 1.

In relation to RQ1, from these results, we concluded that the differences between NBS and BS were statistically significant for the very case of competence in communication and language (CCL) due to the fact that the

p-value was less than 0.001, and NBS seemed to perform better than BS. For the rest of the competences (PC, CC, CACEC, PSLLC), the differences were not statistically significant, and they showed a certain harmony with the study of

Admiraal et al. (

2006).

Based on the collected data, students from the bilingual school (BS) perceived a relatively lower development of key competences in the realms of culture and language learning, as well as cross-cultural awareness, compared to the students from non-bilingual schools (NBS). Nonetheless, the differences were not statistically significant for the cultural and language components of PC, CC, CACEC, and PSLLC.

3.2. Teachers’ Perceptions on CLIL Programmes in Terms of Training, Competencies, Resources, and Results

This section aims at providing an answer for RQ2 and RQ3, which focused on teachers’ insights on bilingual programs. Questionnaire B contained four blocks of questions that can be grouped into the following four main categories: the training teachers have received, the extent to which they feel they are competent to deliver courses under the CLIL approach, their perceptions on human and material resources, and the impact of the program in terms of culture and language learning.

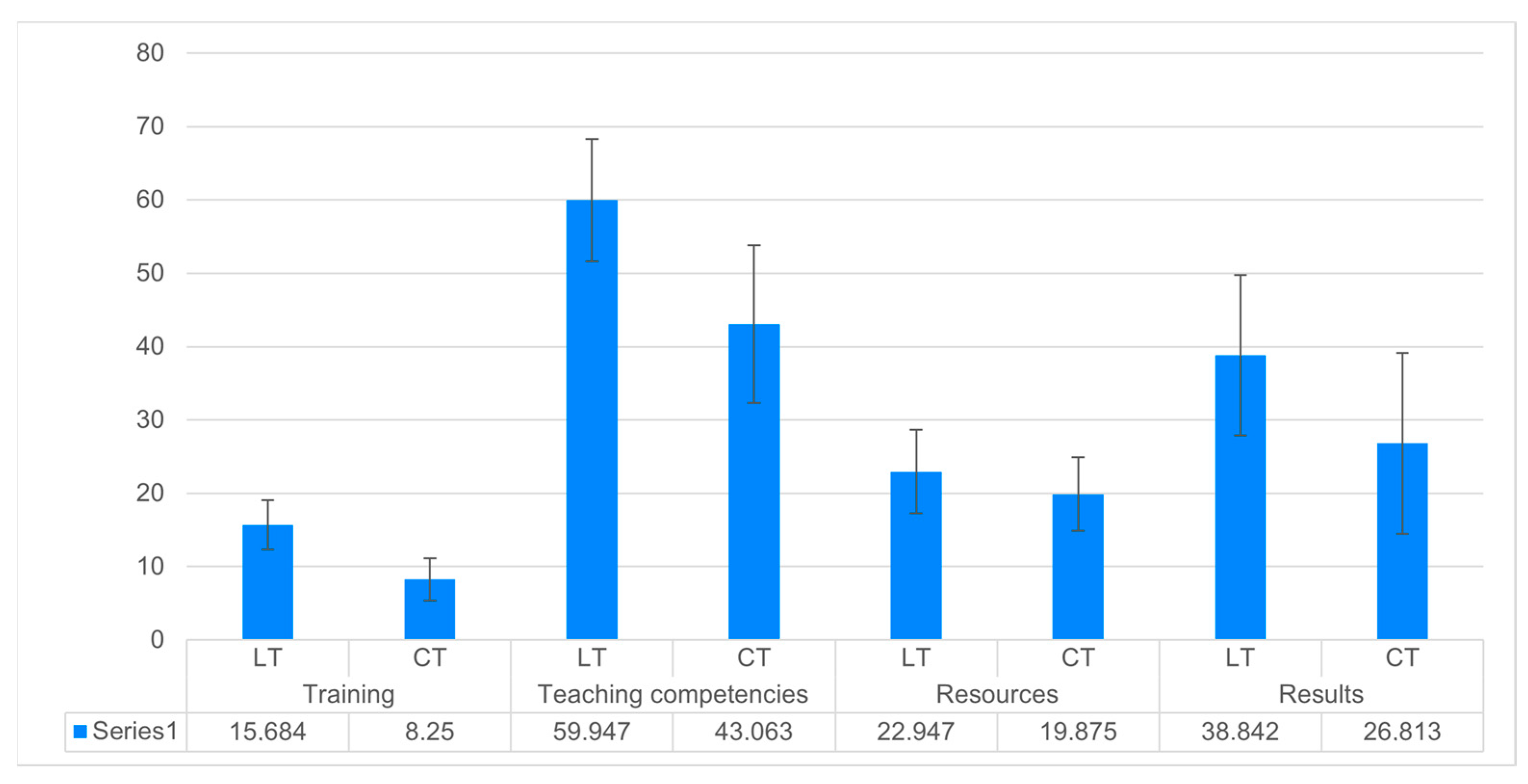

The results were divided into the perceptions of content teachers (CT) and language teachers (LT) as shown in

Figure 3. As has been formerly mentioned, the sample comprised 35 Andalusian in-service teachers, with 54.3% (N = 19) having received specific language training and the remaining 45.7% (N = 16) being content teachers. The first group consisted of teachers who have a degree on a specific non-language subject such as Physics, Law, History, or Geography, whilst language teachers (LT) were the ones who received specific training on teaching a language (belonging to this group are teachers who have a degree in Primary Education majoring in Foreign Language Teaching, and teachers who have studied Philology, Translation and Interpreting Studies, Linguistics, or related degrees).

From the data shown in

Table 2, we may infer that LT have a more favorable perception of CLIL programs compared to CT, and these differences are statistically significant in areas such as training for teaching in CLIL contexts, their perception of their own teaching competencies and their suitability for CLIL contexts, and their insights on the results of the CLIL program. Nonetheless, the difference between the perceptions of LT and CT is not statistically significant for the case of the human and material resources. Apart from studying the convergences and divergences of content and language teachers’ perceptions, it is important to investigate the variations in perceptions of bilingual programs according to teachers’ English proficiency level.

An ANOVA analysis was also performed, as the reader may observe in

Table 3. This analysis attempted to delve into the possible relationship between the level of English proficiency (according to the CERFL) and the perception of the different dimensions involved in our study. The results showed that the English proficiency levels might be related to teachers’ perceptions of their own competencies for teaching (

p-value = 0.001) under the CLIL approach, and this relation is statistically significant. Notwithstanding, the ANOVA results indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in language proficiency levels with regard to the training received (

p-value = 0.276), available resources (

p-value = 0.183), or teachers’ perceptions of the program’s outcomes (

p-value = 0.157).

It is of interest to deepen our understanding of the different items that compose the four dimensions to have a better understanding of the results that have been analyzed.

Table 4 focuses on the perceptions of teachers of their training on the implementation of CLIL courses, bilingual education, intercultural competences, and language learning. Participants should evaluate each and every item by making use of a 5-point Likert scale, 0 being the minimum degree of agreement and 5 being the maximum degree of agreement.

As we can observe in

Table 4, the perception of each item was average. Nevertheless, when it comes to exploring the descriptive results for the dimension of teaching competencies (

Table 5), we found that teachers rated the training they received for the implementation of CLIL programs the highest (M = 2.657, SD = 1.533), but they did not seem to agree with the fact of having received specific training for developing the intercultural competence of their students (M = 2.200, SD = 1.132).

Teachers perceived (

Table 6) that they did not have enough time to prepare their CLIL-based lesson during the school day (M = 1.486, SD = 0.781). They were aware of the fact that the participation in a CLIL program required an extra workload outside the workday (M = 4.257, SD = 1.094), and they did not specially show a firm desire to assume an extra workload for the preparation of this sessions (M = 2.886, SD = 1.323). It is of uttermost importance to delve into their language skills, and they perceived to have an average development of the following: oral production (M = 3.543, SD = 1.400), written production (M = 3.771, SD = 1.352), oral reception (M = 3.600, SD = 1.311), and written reception (M = 3.800, SD = 1.368). They thus declared to have a better performance when it comes to written reception, but they affirmed to have a worse performance in terms of oral production, and it is of paramount importance to bear in mind that in CLIL programs oral production skills play a key role as they are expected to create an immersion-like environment.

It is also important to deepen our understanding of the perceptions of teachers of the impact of the CLIL program (

Table 7). Teachers’ perceptions showed that CLIL programs did not foster motivation (M = 2.686, SD = 1.409), but from the evidence presented, it can be inferred that they did have a positive impact on the development of language skills, specifically on oral production (M = 3.086, SD = 1.380) and oral reception (M = 3.257, SD = 1.462). Nonetheless, they did not particularly agree with the fact that students assimilated concepts better in bilingual programs (M = 2.571, SD = 1.367).

The data interpretation in this section should be approached due to the limited sample size. Even though the sample is not sufficiently large enough to draw definitive conclusions, it is useful because it may pave the path towards future studies focusing on interculturality, language, and culture learning in CLIL programs, taking the key competences of the Education Acts into consideration.

4. Conclusions

The results obtained in this study could be perceived as counterintuitive, which is why it is important to contextualize them.

Fernández-Sanjurjo et al. (

2019) discovered that elementary education students enrolled in CLIL programs exhibited a marginally lower level of science proficiency in their first language, as evaluated by the researchers, compared to non-CLIL students. Even though

Fernández-Sanjurjo et al. (

2019) warned about the importance of interpreting the results carefully because of the size of their sample, as we said the same in our study, similar results were obtained. On one side of the spectrum, the results from students’ perceptions of their performance showed that there are not statistically significant differences between the bilingual and non-bilingual group, except for the CCL in which the NBS was perceived to perform better. On the other side of the spectrum, teachers affirmed to lack the time to prepare their CLIL lessons properly, and they also put a special emphasis on the difficulties of including intercultural elements in lesson planning and the lack of training in this regard.

The lack of statistically significant differences in terms of the key competences seem to be aligned with the results obtained by

Admiraal et al. (

2006), as the authors found no statistically significant differences between CLIL and non-CLIL students in terms of learning. In contrast, teachers did not fully agree with the fact that students assimilate concepts better in a bilingual program; thus, they may have negative expectations on the CLIL approach and its potential. Particularly, content teachers were the ones who showed a higher tendency to adhere to narratives of resistance towards CLIL programs, and it is coherent with

Alonso-Belmonte and Fernández-Agüero’s (

2021) study on the negative perceptions of teachers towards bilingual programs. Furthermore,

Pérez Cañado (

2020) conducted a longitudinal study that showed that students who took part in CLIL programs performed better in terms of language skills. The results from our study were harmonious with

Pérez Cañado’s (

2020) research. Additionally, according to teachers’ perceptions, the skills that students developed the most were the oral ones.

With reference to intercultural learning,

Gómez-Parra (

2020) identified two key elements for its development: contact with peers through international exchanges, and the opportunity of having contact with native language assistants. In

Table 6, we can find that teachers perceived that these two elements were not sufficiently enhanced within the current implementations of CLIL programs. It is in this point that we find limitations for the development of interculturality and culture learning, and the elements highlighted by

Gómez-Parra (

2020) should be specifically addressed.

The effectiveness of CLIL programs is undeniable, but they need a proper implementation that requires providing content teachers with specific training on CLIL from a practical perspective, appropriate funding, and more human and material resources. In this regard, it is crucial to provide teachers with sufficient time to take on this workload within their teaching schedules, as well as hiring additional staff to create room in the schedule and enable the proper implementation of CLIL programs.

We consider the research topic of this study of interest due to the fact that it explored the impact of bilingual programs on language and culture learning, as well as on the development of interculturality within the framework of the Education Acts. Notwithstanding, the study has its limitations since validated instruments have not been used because the specificity of the new Education Act (LOMLOE) required the creation of ad hoc tools for the study.

In conclusion, it is important to take into consideration that it is key to provide teachers with sufficient time to manage the workload. Furthermore, the consideration of hiring additional teachers could be beneficial to create sufficient time in the schedule for providing students with personalized attention. It is also of paramount importance to provide content teachers with specific training on the implementation of bilingual programs. In terms of language skills, the development of oral skills should be addressed, as teachers need to be fluent to deliver CLIL-based courses effortlessly.

For future studies, it is important to increase the sample size and to measure not only perception, which can be biased, but also empirical levels of language proficiency, culture learning, and intercultural awareness of students.