4.1.1. Pauses

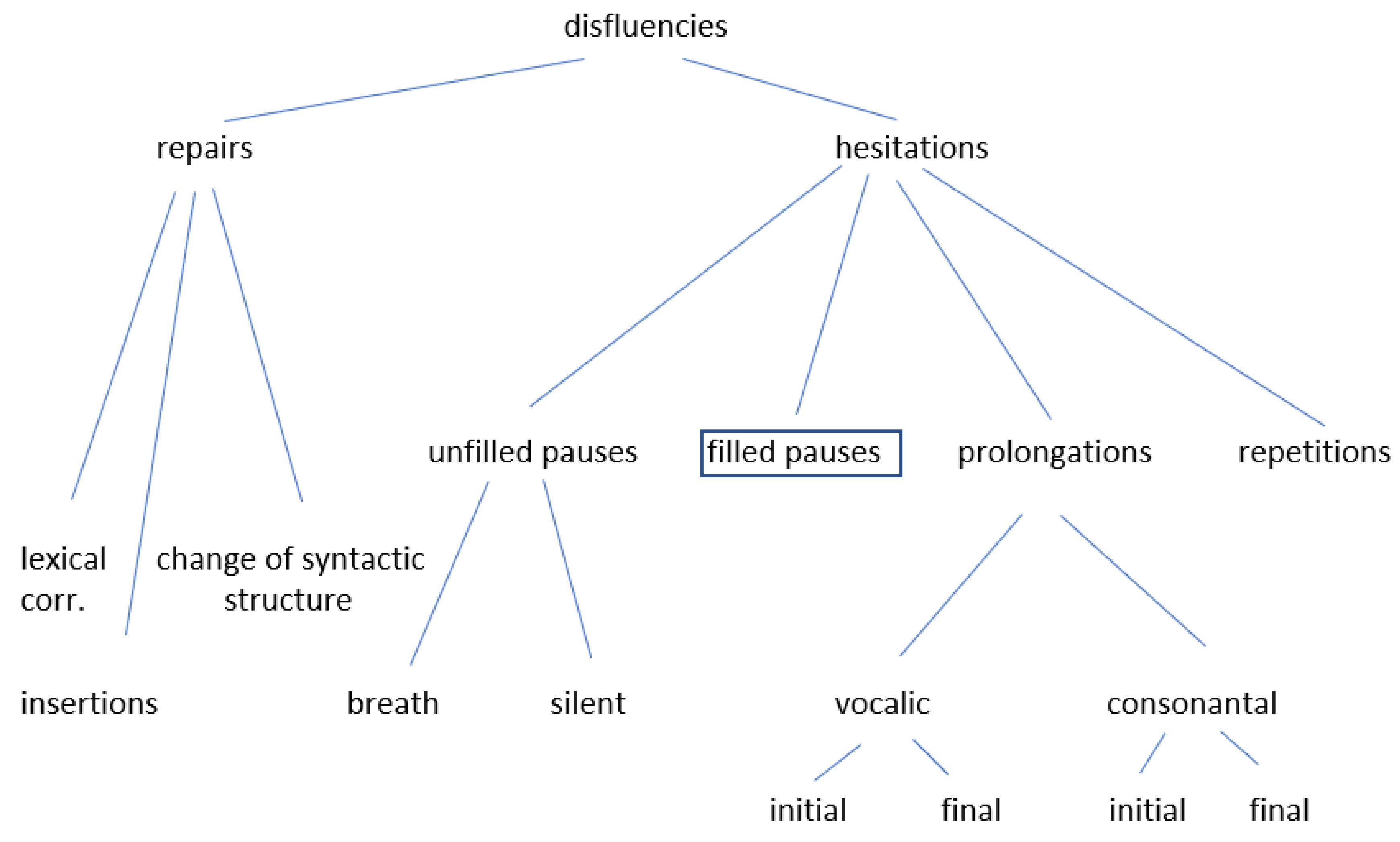

A major distinction between hesitations can be drawn according to whether or not they contain vocalizations. They may be characterized by the absence of audible articulatory activity or by the presence of some kind of vocalization.

Unfilled pauses are pauses without vocalization, i.e., sound generated in the larynx and/or the vocal tract. In other words, they are truly silent or serve the purpose of breathing. The role of breath pauses is somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, they contain signal, but on the other hand, the origin of this signal is neither the larynx nor the vocal tract. In other words, there is no “phonetic activity”, as

Trouvain et al. (

2016) put it. Therefore, we concur with those researchers and categorize them as unfilled pauses.

For an analysis of hesitation behavior, the frequency of occurrence and duration of unfilled pauses is relevant.

Breath pauses primarily serve a physiological need, but they may be used for planning purposes at the same time. From a forensic perspective, the issue of individuality in breathing is of interest. There are several studies which demonstrate that breathing patterns are highly individual (

Dejours et al. 1961;

Shea et al. 1987;

Shea and Guz 1992;

Benchetrit et al. 1989;

Benchetrit 2000;

Eisele et al. 1992;

Trouvain et al. 2019).

Dejours et al. (

1961) coined the term “personnalité ventilatoire” to describe the individual dynamics of breathing. Shea and colleagues (

Shea et al. 1987;

Shea and Guz 1992) confirmed those findings, which were established based on the physiological examination of quiet breathing, and demonstrated their validity for the deepest type of non-REM sleep (S4 sleep) as well. They attempted to define the cause for individuality in breathing and posited that the size and structure of the airways and lungs, as well as the mechanics of breathing, play a key role (

Shea and Guz 1992, p. 287). This is a potentially important finding in the context of forensic analysis, because it demonstrates that between-subject variability is likely to exceed within-subject variability. However, the results cited so far were established through physiological measurements, and they refer to the frequency and depth of inhalations alone. The latter are obviously not available in the forensic environment. With the forensic application in mind, one may ask how often the speaker inhales and if the preferred pathway is through the nose, the mouth, or both, and in which sequence. Nasal inhalation followed by oral inhalation is often accompanied by a click sound at the transition, whereas the same is not true for the opposite sequence.

Kienast and Glitza (

2003) used auditory and acoustic phonetic methods to analyze speech breathing. They studied the frequency of speech breathing as well as the preferred pathway. They concluded that the pathway of air (nose and/or mouth) and the acoustic structure of the breathing noise are the best “candidates” for characterizing the individual speaker. This shows that the physiological findings are mirrored by the acoustics of speech breathing.

Lauf (

2001) studied the duration, frequency, and spectral composition of breath pauses in read speech and found that speakers fall into different categories (e.g., with respect to the duration of inhalation), but the parameters she studied were not suitable to distinguish individuals.

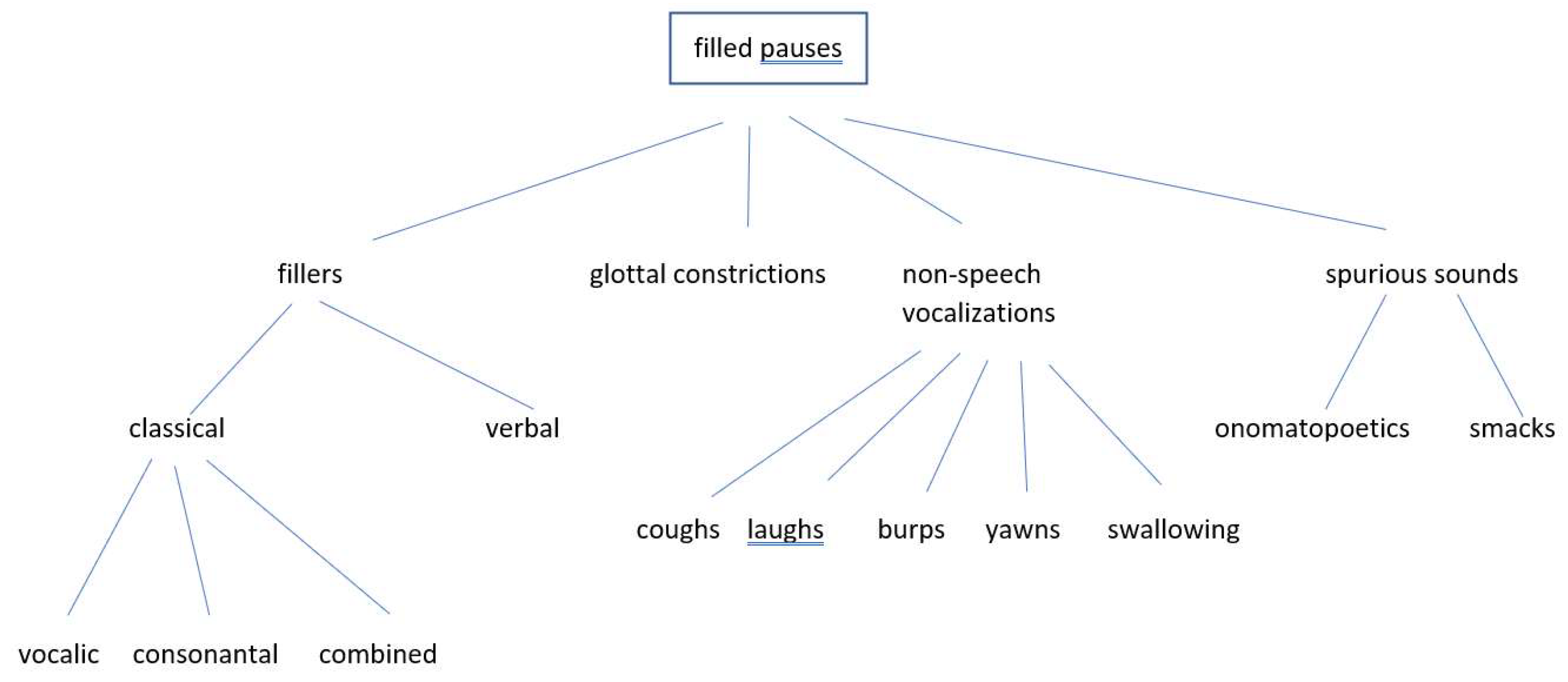

Filled pauses are pauses containing vocalized sound which may or may not be preceded and/or followed by a period of silence. They can be subdivided into various categories, some of which are discussed in detail below. The most frequent ones are pauses containing fillers in the traditional sense, but they also include non-speech vocalizations and glottal constrictions. Finally, pauses which are filled by a variety of spurious sounds fall into this category.

If one looks at data sets of conversational speech, it is quite clear that the two items discussed so far are by no means the only fillers that may occur. There are many more hesitation markers beyond the “classical” set, which may be much more idiosyncratic than the frequently studied fillers

äh and

ähm. Perhaps the filler most frequently encountered beyond those two in German is

mh. In our data, there are speakers who use

mh more often than

äh. Considering this distribution, the present authors find it difficult to understand why the nasal filler is not routinely included in the analysis and consider it on equal footing with

äh and

ähm.

Belz (

2021) takes it into account but assigns a marginal role to it. Incidentally,

mh was regularly included in some early studies (e.g.,

Maclay and Osgood 1959;

Blankenship and Kay 1964), but it somehow “got lost” thereafter. Like the other two,

mh may or may not be preceded by a glottal stop ([ʔmmm] vs. [mmm]).

4 Here is an example, taken from our recordings:

| (1) | Als ich von dem Sonnenhof nach Steinbach zurück lief, mh, sah ich einen Hubschrauber über mir. ‘When I returned to Steinbach from the Sonnenhof, mh, I saw a helicopter above me’. (S #1)5 |

There is another group of fillers which is addressed very rarely, and if so, it is addressed in a controversial manner.

Clark and Fox Tree (

2002) call them “collateral signals” of which the speaker is not aware.

Stenström (

2012) talks about “verbal fillers”. This seems to be a more suitable term and is therefore used in the present contribution.

Verbal fillers are multifunctional lexical items which “can also have various discourse, pragmatic and interactional functions” (

Stenström 2012, p. 540). When used as fillers, “[…] they add nothing to the propositional content of an utterance, only to the pragmatic content […]” (

Stenström 2012, p. 540).

We discuss the most frequent—and therefore, the most relevant—verbal fillers in more detail. In German,

und and

ja are prime examples. Both may adopt different roles, and the categorization of

ja in particular as a part of speech is controversial.

Und is a connective in the first place, of course, but it may be used completely devoid of its lexical meaning, as is demonstrated by an example from our data:

| (2) | […] und es es riecht nicht, ähm ja und und äh es es soll ja auch ich mein ich weiß es ja selber nich […] ‘[…] and it it doesn’t smell, um well, and and uh it it should also I mean I don‘t know myself […]’. (S #7) |

Discussing the full range of use of

ja in German is well beyond the scope of this contribution,

6 but the aspects which are most relevant to the classification made here are mentioned. In the first place,

ja signals affirmation in response to a question. In this context, it is stressed.

| (3) | Kommst Du mit?—Ja. ‘Are you coming along?—Yes.’ |

Beyond that,

ja is a modal particle serving different purposes depending on the lexical stress. When stressed, it is used as an intensifier and conveys a strong urge, possibly even implying a threat on the part of the speaker, as in the following example:

| (4) | Pass auf! ‘Be careful!’ vs. |

| (5) | Pass ja auf! ‘You had better be careful’ or ‘Do be careful’. |

When unstressed,

ja may be used to indicate that the speaker is stating the obvious and expects the listener to be privy to that information. Note the difference between:

| (6) | Bayern München hat das Spiel gewonnen. ‘Bayern Munich won the game‘ [I am telling you] and |

| (7) | Bayern München hat ja das Spiel gewonnen. ‘Bayern Munich won the game‘ [as you know]. |

Another use of

ja signals speaker attitude, specifically verbal irony, as is evident from the following example.

| (8) | Das kann ja heiter werden! ‘This is really going to be fun, ha’. |

Yet another variant of the German

ja is its use as an interjection. In this capacity,

ja may be replaced by

tja.

| (9) | (T)ja, was soll man dazu sagen? ‘What can you say to this?’ |

But

ja may also be used as a question tag, replacing

nicht,

nicht wahr, etc.:

7| (10) | Ich war von dem langen Flug völlig übermüdet, ja, und habe mein Auto im Parkhaus nicht mehr gefunden. ‘I was very exhausted from the long flight, you know, I could not find my car in the parking garage.’ |

| (11) | […] und dann kommt noch etwas Butter dazu, ja […] ‘[…] and then you add a little butter, okay?’ (S #1) |

Finally,

ja may serve as a filler, as in (12) and (13) below:

| (12) | […] wenn man, ja, die Grenze erreicht […] ‘[…] once you, uh, get to the border […]’. (S #1) |

In our material, it was occasionally replaced by

pja. This demonstrates once again that there is no propositional content left in this usage of

ja.

| (13) | […] wenn da geraucht wird, ähm muss man ja nicht hingehen, wenn man das nicht äh dulden möchte, und, ja, wie gesagt ähm, ich bin halt gegen das Rauchen […] ‘[… ] if people are smoking there, uh, you don’t have to go there if you are not willing to uh tolerate that, and, uh, as I said, um, I am opposed to smoking […]’ (S #4) |

This last example has two instances of ja side by side: The first is of the same kind as (7) above, whereas the second is a filler.

The use of ja as a filler differs from its use as a modal particle in several respects. First of all, this kind of ja is usually preceded or followed by a pause. Just like in most “common” fillers, it has a lower F0 than the immediate vicinity. Furthermore, the intonational phrase, but not necessarily the syntactic phrase, is interrupted. In its capacity as a hesitation marker, ja cannot be replaced by other expressions signaling consent, such as freilich, jawohl, okay, or japp.

In our materials,

ja as a filler was often accompanied by a second filler.

| (14) | Ich würde dann […] erst mal anfangen äh, ja, erst mal mit der Grundfarbe. ‘I would start out with uh, well, the foundation first of all.’ (S #2) |

| (15) | Das Schneewittchen hat natürlich aufgemacht und ähm, ja, ähm die hat gefragt […] ‘Snowwhite opened the door, of course, and um um um she asked […]’. (S #4) |

But

ja is not the only additional option for a verbal filler. There are numerous lexical items, such as

halt stopp,

Moment (which outrightly expresses the speaker’s need for more time), or even

wie sagt man gleich, etc., which lend themselves to be used as hesitation markers. In English,

well,

okay, or

how do I put it as a conscious marker of the speaker’s search for words might adopt this role, as in (16).

| (16) | I believe there were, well, maybe 200 guests at the wedding. |

Hesitation markers do not necessarily occur as singular events. They may be repeated, and the same is true for other lexical items, as in (17), which is a quotation from Katharina Thalbach, a well-known German actress and director. These repetitions also serve the purpose of gaining time and can therefore be considered hesitations. They may be combined with fillers, and fillers may be repeated, as in (18):

| (17) | Wo is sein sein Fundus, mit dem er arbeitet, und wo is sein sein Reser- sein sein sein sein Becken, aus dem er die Dinge holt? ‘Where is his his fund that he is working with and where is his his reser- his his his his pool that he is getting things from?’ |

| (18) | […] und das ähm mh mh naja, ja im Augenblick ist das ein bisschen ein zäher Roman. ‘[…] and this um mh mh, well, right now this is a bit of a boring novel’. (S #1) |

Stenström (

2012, p. 541) mentions that repetitions mostly affect function words. Without having addressed this question systematically, it can be said that this appears to be the case for our materials as well.

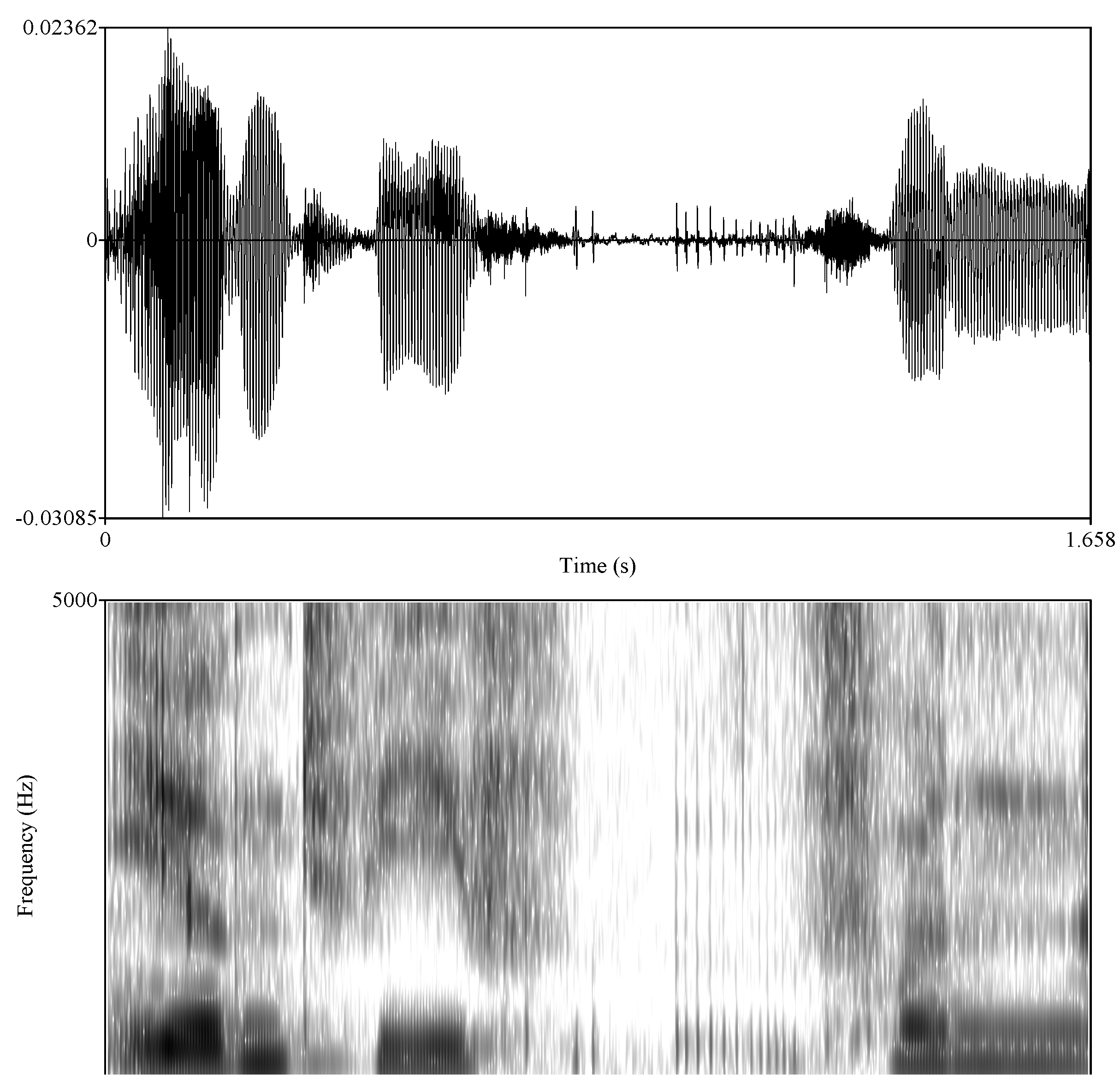

One further type of filler, which has so far been largely neglected in the literature, can be described as increased glottal constriction with low subglottal pressure. In fact,

Belz (

2021) is the only author who describes precisely this case. He considers it as one of the “glottal fillers”.

The result is a very short creaky sound which is distinct from a creaky

uh or

um by a shorter duration and a lesser degree of periodicity. It does not appear to possess any specific vowel quality but a transitional narrowing of the vocal folds with insufficient subglottal pressure to achieve regular vocal fold vibration. It could be interpreted as a false start in the sense that the speaker adducts the vocal folds in preparation for speaking, then realizes that they are not ready to start and abducts the vocal folds again. Here is an example (19), which is also shown in

Figure 3:

| (19) | [ …] irgendwie vvv <constr.> vonn [,,,] ‘[…] somehow fff <constr.> frommm […]’ (S #6) |

Naturally, there is the full repertoire of nonverbal vocalizations, such as clicking, laughing, coughing, throat clearing, swallowing, yawning, and possibly even burping, which can all be used to fill pauses. (cf.

Trouvain 2014). There is a difference between clicking and laughing on the one hand and the rest on the other hand, though. The last five listed above usually fulfill a physical need and can therefore not be regarded as hesitation markers in a strict sense. They may also contribute to the idiosyncratic behavior of a speaker in rare cases.

8There is still another way of (repetitious) hesitating, and this is by producing spurious sounds such as

| (20) | [ʙ̥ʙ̥ʙ̥] in: […] ach so, das war ja letzte Woche, mh, j- [ʙ̥ʙ̥ʙ̥] ja ja an einem Tag essen wir wahnsinnig gerne immer in der Woche mh einen Salat. ‘[…] oh yes, that was last week, mh, y- [ʙ̥ʙ̥ʙ̥], well, yes, we really like to eat a salad mh once a week […]’ (S #1) |

This is a type of hesitation marker which the present authors have not seen mentioned in any previous publication, even though it is by no means a hapax legomenon in our materials.

If hesitations serve the purpose of gaining time in order to plan the upcoming utterance or search for the adequate lexical item, it is quite clear that non-linguistic sounds or fillers are not the only means to achieve this goal. Instead of inserting an element, existing elements may be lengthened. And yet, Eklund seems to have been the first to draw detailed attention to this (

Eklund 2000,

2001). He points out that prolongations are more common than most other types of hesitations, outnumbered only by filled pauses and unfilled pauses (

Eklund 2000;

Eklund and Shriberg 1998).

Betz (

2020) observes that prolongations, such as verbal fillers, may serve various purposes. He distinguishes disfluent lengthenings from accentual ones and forced-alignment errors. The present contribution addresses the first type only.

Stenström (

2012) states that prolongation typically affects conjunctions. While this is certainly true for

und, a superficial look at the data for the present study shows a large number of counterexamples. This certainly merits looking into in future research.

According to

Duez (

1993), prolongations work like pauses or fillers do.

Clark and Fox Tree (

2002) consider them as a phonological alternative to fillers. This constitutes one of their arguments that fillers are regular words.

Betz et al. (

2017), on the other hand, follow

Eklund (

2001) and argue that durations of fillers and lengthened segments are fundamentally different. As a consequence, they consider them to be different in function.

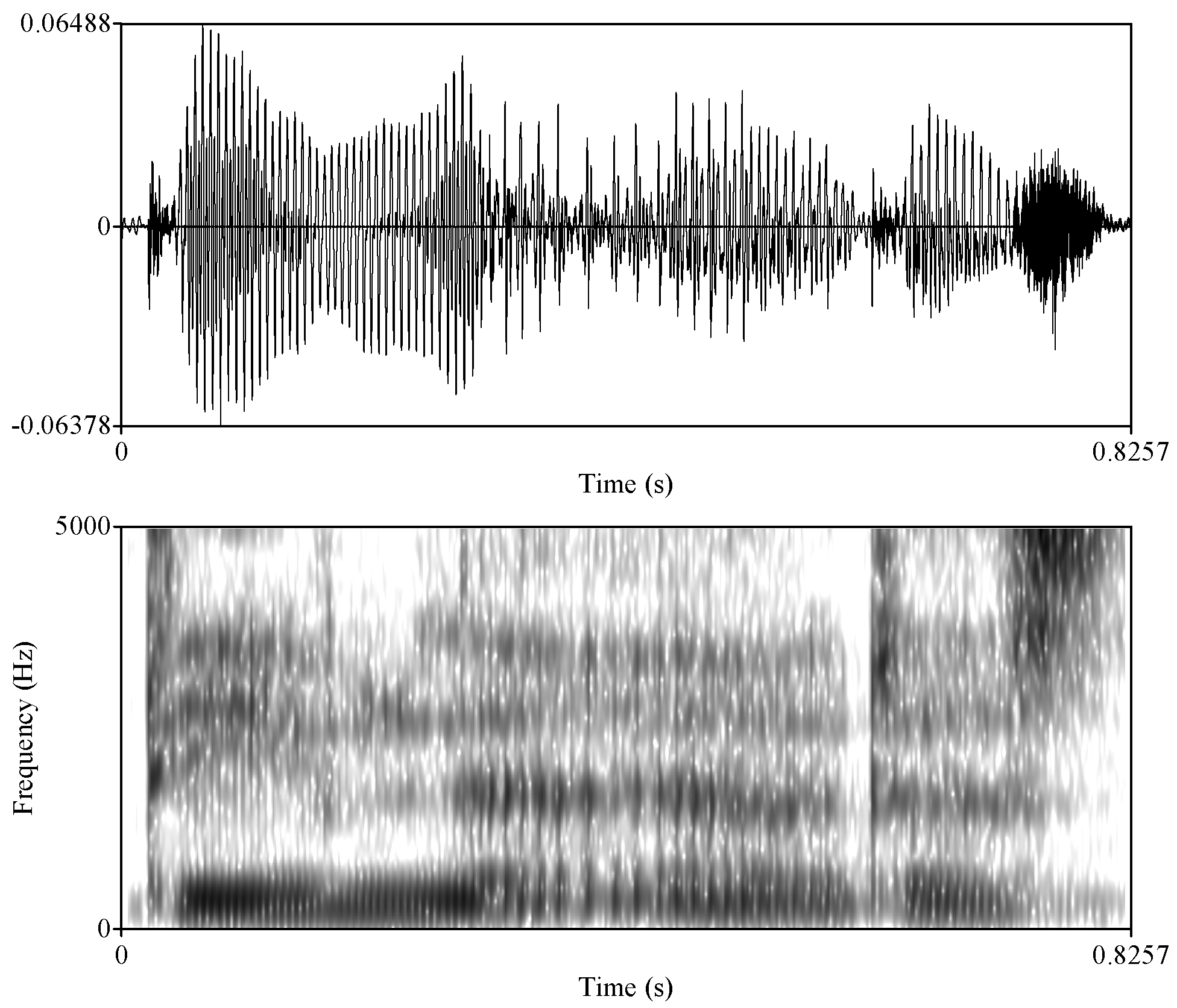

Prolongations, however, are not random. It seems reasonable to establish the sound class that is lengthened (vowels or consonants), as well as the position of the lengthened sound within the syllable (initial vs final). The following examples from the recordings analyzed in this contribution illustrate the lengthening of a word-initial or word-final vowel or consonant:

| (21) | Initial vowel prolongation: […] uuuund damit er auch nicht abhauen konnte aus diesem Käfig. ‘[…] aaaand so that he couldn’t escape from this cage’. (S #4) |

| (22) | Final vowel prolongation: Xanten waaa ja eine alte Römerstadt. ‘Xanten issss a town going back to Roman times’. (S #1) |

| (23) | Initial consonant prolongation: Das ist halt ffffürn Rücken und für die Knie und für alles Mögliche gut. ‘This is good ffffor your back and for your knees and for all sorts of things’. (S #2) |

| (24) | Final consonant prolongation: […] weil ich ja Nichtraucher bin und eigentlichchchch ähm dieses äh diese Rauchschwaden nicht leiden kann […] ‘[…] because I am a nonsmoker and I really can’t stannnnd9 this uh these clouds of smoke […]’. (S #1) |

Prolongations may be combined with fillers. The precise way in which this is happening would merit looking into. It could well be that there is some sort of implicit signaling of trouble first (by the prolongation), and if that turns out to be too short, it is complemented by a filler proper.